Abstract

The focus of this chapter is on the question types used most frequently at public inquiries, taking the C. Diff Inquiry as a case study. Murphy shows that questioning practices are different to those found in criminal trials, but also that there is differential treatment of witnesses who might be considered blameable vs. those who are blameless. He finds that this is, in part, due to the need for counsel to privilege certain evidence, maintain the chronology of the witnesses’ statements and because of the relative vulnerability of certain core participants. Murphy also highlights how counsel are careful in how they frame criticism so that it does not seem that the inquiry has come to a prejudgement of who is to be blamed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution.

Buying options

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Learn about institutional subscriptionsNotes

- 1.

Some legal scholars use the term inquisitorial in opposition to prosecutorial and use it to describe usually civil investigations which are focussed on fact-finding. However, given the strong association of inquisitorial and inquisition, i.e. questioning someone in a harsh manner, I will eschew this terminology. Instead, I will prefer less adversarial, or non-adversarial whilst adding the caveat that this description is also less than adequate because I am seeking to explore this aspect of inquiry talk in the chapter. The use of non-adversarial should not be seen to prejudice this investigation.

- 2.

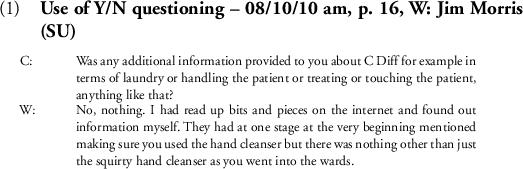

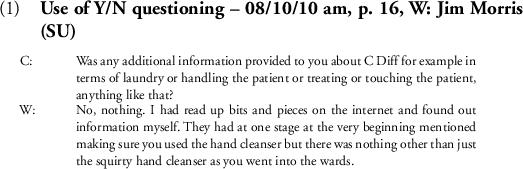

A note on the information given with examples from this point on: each extract is given a title summarising its reason for inclusion, the title of the Inquiry from which it is extracted, the date it was produced and the page that it can be found in the inquiry transcripts. Links to these transcripts are provided in Appendix B. Counsel’s contributions are labelled C throughout the text, and witnesses’ W. The name of each witness is provided in the example preamble. In the case of the C. Diff Inquiry, witnesses are identified as either being service users (SU) or hospital staff (H)—I will explain this categorisation in Sect. 3.9

- 3.

It is to be noted here that I believe these questioning types hold across all inquiries. Indeed I have analysed a further three inquiries—Leveson Inquiry, Hutton Inquiry and Shipman Inquiry —and find that the same question types can be found in those inquiries. However, given that I have not exhaustively carried out the same analysis for all inquiries, I will hedge my comments by noting that what I have to say here relates definitively to the C. Diff Inquiry and may apply across the piece. This further work I leave to other interested scholars.

- 4.

Although, note that she does not commit herself to this—‘the professional nursing role should be a role in its own right’ (my emphasis) gives rise to an implicature that it is not possible to do both roles, but this is cancellable. The witness could have continued with something like ‘because that would mean the job was done better, but it is perfectly possible for someone to do both roles’. I submit that in a criminal court, counsel would have ‘jumped on’ this sort of lack of commitment and sought a more explicit response from a witness.

- 5.

In lieu of the official transcript, I produced the example from a publicly available video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h6jCX7xvuEU. Last accessed: 14 January 2018.

- 6.

National Health Service Trusts are public sector bodies which are responsible for the running of healthcare establishments. In the case of the Northern Hospitals, these are overseen by the Northern Health and Social Care Trust—a body whose executives are medical professionals, but whose non-executive board members come from more varied backgrounds. For ease of reference, I make no distinction between staff working for the Trust, and staff who worked in the hospitals run by the Trust. I refer to all in this category as hospital staff.

- 7.

Counsel is interested in these arrangements because a patient infected with C. Diff should not be using a communal toilet because of the risk that poses in spreading the infection to other patients on the ward.

- 8.

Example 56 does ask questions about information provided on laundry as declaratives. However, these come later in the witness’ testimony, after he has already been asked these questions in the form described here. For instance,

- 9.

In Chapter 5, I will explain in some detail what I view as the link between criticism and blame.

References

1911. Perjury act.

Archer, Dawn. 2005. Questions and answers in the English courtroom (1640–1760). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Atkinson, Maxwell, and Paul Drew. 1979. Order in court: The organisation of verbal interaction in judicial settings. London: Macmillan.

Beer, Jason. 2011. Public inquiries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cavalieri, Silvia. 2009. Reformulation and conflict in the witness examination: The case of public inquiries. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law 22: 209–221.

Cavalieri, Silvia. 2011. The role of metadiscourse in counsels’ questions. In Exploring courtroom discourse: The language of power and control, 79–110. Abingdon: Routledge.

Drew, Paul. 1992. Contested evidence in courtroom cross-examination: The case of a trial for rape. In Talk at work: Interaction in institutional settings, ed. Paul Drew and John Heritage, 470–520. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eades, Diana. 2010. Sociolinguistics and the legal process. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Ehrlich, Susan, and Jack Sidnell. 2006. I think that’s not an assumption you ought to make: Challenging presuppositions in inquiry testimony. Language in Society 35: 655–676.

Hansen, Maj-Britt Mosegaard. 2008. On the availability of literal meaning: Evidence from courtroom interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 40: 1392–1410.

Hansen, Maj-Britt Mosegaard. 2016. Patterns of thanking in the closing section of U.K. service calls: Marking conversational macro-structure vs. interpersonal relations. Pragmatics and Society 7: 664–692.

Huddleston, Rodney, and Geoffrey Pullum. 2002. The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kendrick, Kobin. 2015. Other-initiated repair in English. Open Linguistics 1: 164–190.

Levinson, Stephen. 1979. Activity types and language. Linguistics 17: 365–399.

Levinson, Stephen. 1983. Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Luchjenbroers, June. 1997. In your own words: Questions and answers in a Supreme Court trial. Journal of Pragmatics 27: 477–503.

Palmer, Frank. 1986. Mood and modality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. 1985. A comprehensive grammar of the English language. London: Longman.

Raymond, Geoffrey. 2003. Grammar and social organization: Yes/no interrogatives and the structure of responding. American Sociological Review 68: 939–967.

Schegloff, Emanuel. 2007. Sequence organization in interaction: A primer in conversation analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schegloff, Emanuel, Gail Jefferson, and Harvey Sacks. 1977. The preference for self-correction in the organization of repair in conversation. Language 53: 361–382.

Schreiner, Oliver. 1967. The contribution of English law to South African law and the rule of law in South Africa. London: Stevens & Sons.

Sidnell, Jack. 2010. Conversation analysis: An introduction. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Strömbergsson, Sofia, Anna Hjalmarsson, Jens Edlundand, and David House. 2013. Timing responses to questions in dialogue. Proceedings of Interspeech 2013: 2584–2588.

Travers, Max, and John Manzo. 1997. Law in action: Ethnomethodological and conversation analytic approaches to law. Abingdon: Routledge.

Woodbury, Hanni. 1984. The strategic use of questions in court. Semiotica 48: 197–228.

Zweigert, Konrad, and Hein Kötz. 1998. An introduction to comparative law, 3rd ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Murphy, J. (2019). Questioning. In: The Discursive Construction of Blame. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50722-8_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50722-8_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-137-50721-1

Online ISBN: 978-1-137-50722-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)