Abstract

Dynamics of radiocesium in wild mushrooms, especially in mycorrhizal fungi, in forest ecosystems were investigated for 5 years after the Fukushima nuclear accident, in relation to substrates such as litter, soil and wood debris. Some mushroom species contained a high level of radiocesium in the first or second year, and then the radiocesium content decreased. Changes in radiocesium activities were ambiguous for many other mushrooms. Radiocesium accumulation with time was not common contrary to expectations. Reduction of radiocesium activities in litter and increase in mushrooms and soils, i.e. transfer of radiocesium from litter to mushrooms and soils, was recognized in the first and second year, but it was not obvious in subsequent years. Radiocesium accumulated in several mushroom species, especially in mycorrhizal fungi, while radiocesium in the other mushrooms did not exceed those in the neighboring forest litter. Similar differences in radiocesium level among mushroom species were observed in relation to 40K levels, though 137Cs/40K ratio in mushrooms was lower than in O horizon, but at the same level of the A horizon in general. These facts suggested differences in the mechanisms of cesium accumulation. Residual 137Cs due to nuclear weapons tests or the Chernobyl accident still remained in mushrooms and soils. From the ratio of the past residual 137Cs, it was suggested that the residual 137Cs was tightly retained in the material cycles of forest mushroom ecosystem, whereas 137Cs emitted from the Fukushima accident was still fluid.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Chernobyl nuclear accident

- Nuclear weapons tests

- Radioactive fallout

- Radiocesium

- The University of Tokyo Forests

- Transfer factor

- Wild mushrooms

12.1 Introduction

Radioactive material released from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant (F1-NPP) accident spread over a wide area of East Japan. Wild mushrooms often contain a high level of radiocesium in even lower contaminated areas. The University of Tokyo has seven research forests located in East Japan, 250–660 km from F1-NPP, where radiocesium contamination is low (0.02–0.12 μSv/hr. of air dose rate 1 year after the accident). These forests are used for many activities including research, education, forest management and recreation.

Radiocesium contaminated wild and cultivated mushrooms is a major concern for consumers of these forest products. Fungi, including mushrooms, are also one of the major and important components of the forest ecosystem. Radioactive contamination of mushrooms should be considered not only from the viewpoint of food but also from the viewpoint of its effects on plants and animals through its circulation in the forest ecosystem. Therefore, we have surveyed radiocesium contamination in relation to mushrooms in the University of Tokyo Forests.

Mushrooms have been reported to accumulate radiocesium (Byrne 1988; Kammerer et al. 1994; Mascanzoni 1987; Muramatsu et al. 1991; Sugiyama et al. 1990, 1994). The transfer factors (TF) for radiocesium in mushrooms were reported to be 2.6–21 in culture tests (Ban-nai et al. 1994). However, the radiocesium concentration ratio in mushrooms relative to the soil was rather low and the ratio was often <1 in a field study (Heinrich 1992). Symbiotic mycorrhizal mushrooms tend to have higher TF of 137Cs than the saprobic fungi in general, though different mushroom species also have widely varying degrees of radiocesium activity (Heinrich 1992; Sugiyama et al. 1993).

Another feature of fungi is the considerable proportion of 137Cs in forest soil is retained by the fungal mycelia, and fungi are considered to prevent the elimination of radiocesium from ecosystems (Brückmann and Wolters 1994; Guillitte et al. 1994; Vinichuk and Johanson 2003; Vinichuk et al. 2005). Thus, fungal activity is likely to contribute substantially to the long-term retention of radiocesium in the organic layers of forest soil by recycling and retaining radiocesium between fungal mycelia and soil (Muramatsu and Yoshida 1997; Steiner et al. 2002; Yoshida and Muramatsu 1994, 1996). In fact, some examples of long-term 137Cs radioactivity persistence in mushrooms in forests and transfer to animals have been reported, whereas that in plants had short ecological half-lives (Fielitz et al. 2009; Kiefer et al. 1996; Zibold et al. 2001).

In previous reports (Yamada 2013; Yamada et al. 2013), radiocesium contamination of wild mushrooms in the University of Tokyo Forests half a year after the Fukushima accident has been summarized. We found rapid uptake of radiocesium in one species of mushroom after the Fukushima accident and residual contamination from atmospheric nuclear weapons tests (NWT) or the Chernobyl accident. In the current study, the dynamics of radiocesium were surveyed over a 5 year period in wild mushrooms and their substrates (litter, soil or wood debris) in relatively low-contaminated forest areas, and features of the dynamics of mushroom contamination were elucidated, paying attention to accumulation and retention of radiocesium in mushroom related forest ecosystems. The raw data of our surveys were presented in Yamada et al. (2018).

12.2 Research Sites and Sampling

Mushrooms appeared in the autumn of 2011–2015 (Table 12.1) and their presumptive substrates, i.e., the O horizon (organic litter layer, called A0 horizon in Japan), the A horizon (mineral layer and accumulated organic matter), and the C/O horizon (mineral layer with a small quantity of organic matter, which is little affected by pedogenic processes (Soil Survey Staff 2014)) of the soil, or mushroom logs were collected from six (in 2011), 5 (in 2012) and 4 (between 2013 and 2015) research forests shown in Fig. 12.1. Figures 12.2 and 12.3 show examples of samples, the appearance of the environment where samples were collected and sample preparation for radioactivity measurement. The concentrations of 134Cs, 137Cs and 40K were determined using a germanium semiconductor detector (GEM-type, ORTEC, SEIKO EG&G, Tokyo, Japan). Distribution of radiocesium deposition and γ-ray air dose rate in 2011 was presented in a previous report (Yamada 2013).

Locations of the University of Tokyo Forests from where samples were obtained

Fukushima NPP, Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant

UTHF The University of Tokyo Hokkaido Forest (Hokkaido), 660 km from F1-NPP, UTCF The University of Tokyo Chichibu Forest (Chichibu), 250 km from F1-NPP, FIWSC Fuji Iyashinomori Woodland Study Center (Fuji) (formerly Forest Therapy Research Institute, FTRI), 300 km from F1-NPP, UTCBF The University of Tokyo Chiba Forest (Chiba), 260 km from F1-NPP, ARI Arboricultural Research Institute (Izu), 360 km from F1-NPP, ERI Ecohydrology Research Institute (Aichi), 420 km from F1-NPP

Sampling of mushrooms and soils

(a) Deciduous mixed forest where Suillus grevillea mushrooms were collected in Hokkaido (UTHF); (b) S. grevillea mushrooms in Hokkaido; (c) litter layer (O horizon) under S. grevillea mushrooms; (d) surface soil (A horizon) under S. grevillea mushrooms; (e) Slices of Amanita caesareoides mushrooms collected in Fuji (FIWSC); (f) Mushroom and soil samples were placed into U-8 containers. (Photo by K. Iguchi (a, b, c, d) and H. Saito (e))

Examples of collected mushrooms and forests where mushrooms grew

(a) Deciduous mixed forest where Russula emetica mushrooms were collected in Chichibu (UTCF); (b) Tricholoma saponaceum mushrooms on flat land in Chichibu; (c) Soil profile in Fuji (FIWSC). O horizon and C/O horizon were observed; (d) Saprobic mushrooms, Pholiota microspora (left) and Pleurotus ostreatus (right), cultivated on the wood logs in Fuji. Wild Armillaria mellea mushrooms were also collected; (e) Mixed forest of Pinus densiflora and Malus toringo on Yamanaka-ko lakeside in Fuji; Suillus luteus and Lactarius hatsudake mushrooms were collected; (f) Abies homolepis forest in Fuji showing Pholiota lubrica mushrooms on a felled tree (g) and on soil (h), and mycorrhizal Lactarius laeticolor mushrooms on soil (i) were collected. (Photo by K. Takatoku (b) and H. Saito (c))

12.3 Gamma Ray Air Dose Rate at the Mushroom Collection Sites (Fig. 12.4)

Gamma ray air dose rate (μSv/h) 1 m above ground level was measured with a dose rate meter (TC100S, Techno AP Co. Ltd., Japan) using a CsI (Tl) scintillation detector. Although considerable variation in dose rate was observed among UTFs due to environmental variation such as geological features, trends of changes and levels in dose rate were similar within each UTF. Similar levels of pre-Fukushima contamination from nuclear weapons tests and the Chernobyl accident were estimated from 137Cs/134Cs ratio in soils in Chiba (UTCBF) and Fuji (FIWSC). Initial air dose rate in Fuji, however, was somewhat lower than that in Chiba, probably due to geological features. Dose rate slightly decreased in Chiba with time, whereas the decrease was not clear in Fuji. However, in 2015, dose rate in Fuji was similar to the dose rate recorded in Chiba. The original dose rate before the Fukushima accident was thought to be low in Fuji and Chiba. Although contamination due to the Fukushima accident did not reach Hokkaido, the dose rate was higher in Hokkaido (UTHF) than that in Fuji and Chiba. One year after Fukushima accident, the dose rate in Chichibu (UTCF) was higher than that in other UTFs, and was over 0.1 μSv/h, especially in high mountain areas, then gradually reduced by about half by 2015. Dose rate may decrease further in Chichibu, as the dose rate due to the Fukushima accident was estimated at approximately 50 nGy/h (0.05 μSv/h equivalent dose rate of radiocesium) in Chichibu (Minato 2011), whereas the dose rate in other UTFs appeared to become almost stable by 2015.

12.4 Dynamics of Radiocesium in Each of the University of Tokyo Forests (Fig. 12.5)

12.4.1 Litter and Soil Layer

Hokkaido (UTHF): We believe no Fukushima-derived contamination reached Hokkaido because 134Cs was not detected. 137Cs was often below the detection limit, and its concentration in the A horizon was similar to the concentration in the O horizon, indicating the contamination in Hokkaido was old from the viewpoint of transfer to the soil. Similarly, 137Cs was regularly detected in mushrooms even at low levels, but 134Cs was not detected. It indicated that radiocesium in mushrooms was from the pre-Fukushima fallout.

Chichibu (UTCF): Radiocesium levels in the O horizon were high (200–4400 Bq/kg DW) half a year after the accident, and then decreased relatively rapidly. At the same time, the A horizon also contained 134Cs (20–120 Bq/kg DW), indicating a rapid transfer to the A horizon because 134Cs derived from past emissions had already decayed. Subsequent transfer to the A horizon was recognized for example in Tricholoma saponaceum-collected site, however, transfer was generally small. It was possible that radiocesium was mobilizing to lower regions such as valleys or colluvial slope because of steep slopes, with the exception of a few sites (e.g., the flat land where T. saponaceum was collected).

Chiba (UTCBF): Radiocesium decreased in the O horizon with time. A certain proportion of radiocesium appeared to transfer into the A horizon even by 2012, however, no clear subsequent transfer was recognized; It might reach a stable condition because of local environmental factors.

Fuji (FIWSC): A unique feature of FIWSC is that a C/O horizon of volcanic Scoria exists instead of an A horizon. FIWSC is covered with Scoria which is a volcanic immature soil ejected from Mt. Fuji. The transfer of radiocesium from the O horizon to the C/O horizon was low (see below). A large proportion of mycorrhizal mycelia may exist in the surface litter layer, and this resulted in mushrooms accumulating a larger amount of radiocesium. Outside of Fuji, heavily contaminated mushrooms have been repeatedly reported around Mt. Fuji despite being a low-contaminated area. A considerable proportion of the contamination was thought to be derived from nuclear weapons testing and the Chernobyl accident.

12.4.2 Mushrooms

Russula emetica in Chichibu had a high level of radiocesium. Soil analyzed from the R. emetica-collection site was also highly contaminated compared with other sites in Chichibu; fallout from the radioactive plume appeared to have deposited here by chance. The dose rate of this highly contaminated site, however, was lower than that of the surrounding sites. The level of 137Cs in Pholiota lubrica, collected in Fuji, which absorbed quite a high level of radiocesium in the first year of the accident, gradually decreased in one site but remained at the initial level for 4 years in another site. Dynamics of 137Cs in the O horizon might reflect the difference because mycelia of P. lubrica was spread widely in the O horizon. Six months after the accident, Fukushima-derived radiocesium concentration in mushrooms was lower than that of soils except for P. lubrica. Some mycorrhizal mushrooms such as Suillus grevillea, S. viscidus, Amanita caesareoides, Lyophyllum shimeji and Lactarius laeticolor in Fuji contained less 134Cs compared with 137Cs. It was concluded that the past contamination remained (See Sect. 12.8).

Trametes versicolor in Chichibu had a low radiocesium concentration in 2011; the majority of the radiocesium seemed to be derived from the Fukushima accident judging from the proportion of 134Cs. The radiocesium content in T. versicolor was high between 2012–2014, indicating the accumulation in mycelia, but decreased in 2015. In other saprobic mushrooms, a high concentration of radiocesium was detected in Sarcomyxa edulis (synonym Panellus serotinus) in the first year of the accident, then the content decreased in 2013 and 2014 to the same level found in T. versicolor. Litter and soils of the sites, where both mushrooms were collected, were contaminated with radiocesium. Several saprobic mushrooms were collected and surveyed in Fuji; In Lentinula edodes, Pleurotus ostreatus, Armillaria mellea and Pholiota microspora, radiocesium level was much higher compared with bark and wood as substrates, except for bark in 2012. Radiocesium concentration was low in L. edodes and P. ostreatus but accumulated in A. mellea. Saprobes are thought to absorb radiocesium in proportion to the contamination level of the substrate. However, absorption seemed low compared with some mycorrhizal fungi. High radiocesium content in A. mellea might be due to the wide distribution of its mycelia in litter and soil, like P. lubrica and several mycorrhizal fungi.

12.5 Dynamics of Radiocesium in the Same Sampling Sites (Figs. 12.6 and 12.7)

Over a four year period (2011–2015), the decrease in radiocesium concentration by physical decay was 0.912 and 0.262 for 137Cs and 134Cs, respectively (calculated from the half-life of both isotopes). 137Cs content of the O horizon gradually decreased with time more than the rate of physical decay in general, whereas the changes of 137Cs level were ambiguous in several sites of Chiba and Fuji. 137Cs was shown to migrate very slowly into the A horizon in Belarus soils after the Chernobyl accident (Kammerer et al. 1994; Pietrzak-Flis et al. 1996; Rühm et al. 1998). In all sites visited in the current study, obvious transfer of radiocesium from the O horizon as well as reduction of radiocesium was not observed in the A or C/O horizon. In the case of mushrooms, Pholiota lubrica in Fuji (1 site) and Catathelasma imperiale in Chiba (1 site) showed a constant reduction in radiocesium level. The radiocesium concentration in European mushrooms increased for a few years after the Chernobyl accident (Borio et al. 1991; Smith and Beresford 2005); one case of P. lubrica and Suillus grevillea in Fuji showed a similar pattern, with an increase in radiocesium once during 2011–2012 and a decrease after 2012. In other sites or other mushroom species, a reduction of radiocesium was not obvious. Because radiocesium activity at each soil depth changes with time, radiocesium activity in different fungal species at different mycelial depths are also expected to vary with time (Rühm et al. 1998; Yoshida and Muramatsu 1994). The variation observed among sites of our field study may be due to geographic and pedological conditions.

The scatter diagram (Fig. 12.7) also showed a decrease of 137Cs with time in general. The decrease was conspicuous especially in O horizon. 137Cs concentration in A horizon was low at an early stage of post-accident and no obvious increase or reduction was observed. These results suggested a part of 137Cs migrated from the O horizon to the A horizon, but a large proportion remained in the O horizon. In the case of mushrooms, considerable variations of the changes in 137Cs level were observed between species.

12.6 The Relationship Between Radiocesium Contamination of Mycorrhizal Mushrooms and Soils (Fig. 12.8)

Mushroom/O or A (C/O) horizon ratio of 137Cs was compared in mycorrhizal fungi, and found to be high in Fuji and low in Chiba. Additional data is necessary on the same mushroom species, for example between Chichibu and Fuji, to reveal what environmental factors caused such differences. The mushroom/O or A (C/O) horizon ratio of >1 was common in Chichibu and Fuji on a dry weight basis. The ratio on a fresh weight basis was approximately equal to one with a wide range. These findings corresponded with the results of a field study in Europe (Heinrich 1992). Heavily contaminated R. emetica detected in Chichibu did not have a high ratio compared with other mycorrhizal fungi. High contamination could have been due to heavy soil contamination rather than a biological feature of this species. P. lubrica in Fuji showed a clear reduction over time for both mushroom/O horizon and mushroom/C/O horizon ratios. In other sites or other mushroom species, reduction in the mushroom/O or A (C/O) horizon ratios were not obvious. A wide ratio range was observed even within the same species, and no obvious radiocesium accumulation was observed in mushrooms over time.

Mushroom/soils ratio of 137Cs concentration

Mushroom/O horizon ratio (a, c) or mushroom/A (C/O) horizon ratio (b, d) of 137Cs concentration on dry weight basis (a, b) or on fresh weight basis (c, d)

No data: either no mushrooms were collected on the site or the radiocesium concentration was below the detection limit

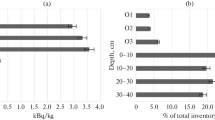

12.7 Possible Mechanism Determining Radiocesium Content – The Relationship Between 137Cs and 40K (Figs. 12.9 and 12.10)

Mushrooms generally had a lower ratio of 137Cs to 40K than the O horizon, but a similar ratio to the A horizon; several mycorrhizal fungi in Fuji such as Lactarius hatsudake and L. laeticolor, which were collected in 2013, were exceptions. For Pholiota lubrica collected in 2011, this fungus absorbed radiocesium very quickly probably due to an abundance of its mycelia in the O horizon. On the contrary, the mycorrhizal Tricholoma saponaceum in Chichibu and Catathelasma imperiale in Chiba, 137Cs/40K ratio in mushrooms was much lower than that in the O and A horizons. It was not clear whether features of the mushrooms or the soil environment resulted in the observed differences between fungi collected from Fuji and Chichibu/Chiba.

On a dry weight basis, 40K concentration seemed high in mushrooms and low in the O or A (C/O) horizons. A reason for radiocesium contamination to be high in mushrooms appears to be because of potassium richness (Seeger 1978). The 40K level, however, was similar for the triparties on a fresh weight basis (Fig. 12.10), suggesting no special mechanism of K absorption. Becauese most K exists as ions in the cytoplasm, the difference was due to a high water content in mushrooms (a water content of 90–95% is common). The high 137Cs/40K ratio observed in Russula emetica was probably induced by heavy soil contamination. On the other hand, mushroom/O or A (C/O) horizon ratios of 137Cs for R. emetica (See Sect. 12.6) was not higher compared with Fuji mushrooms, but much higher compared with mycorrhizal fungi in Chichibu and Chiba. Some physiological or ecological mechanisms for Cs accumulation might work also in the case of R. emetica.

12.8 Features of Radioactive Contamination with Different Date of Fallout (Fig. 12.11)

A high uptake of 137Cs by mushrooms, derived from nuclear weapons tests (NWT), was observed in Japan from the 1950s to 1960s (Muramatsu and Yoshida 1997; Sugiyama et al. 1994; Yoshida and Muramatsu 1996). This contamination originated from the global fallout by NWT, which peaked in 1963 (Komamura et al. 2006), and by the Chernobyl accident in 1986. NWT affected the wild mushrooms in Japan more than the Chernobyl accident. The contribution of the Chernobyl accident was estimated to be in the range of 7–60% and 10–30% on average in each study (Igarashi and Tomiyama 1990; Muramatsu et al. 1991; Shimizu et al. 1997; Yoshida and Muramatsu 1994; Yoshida et al. 1994). In the current study, ecological features of radioactive contamination in mushrooms and in soils were discussed by comparing the contamination from the Fukushima accident with those from NWT and the Chernobyl accident.

Contribution of nuclear weapons tests (NWT), the Chernobyl accident and the Fukushima accident to total radiocesium contamination in 2013

Radiocesium concentration in Russula emetica was shown as one tenth of the actual value (i.e., total 23,400 Bq/kg DW)

No data: radiocesium concentration was below the detection limit

Shortly after the Fukushima accident, a large proportion of total 137Cs in the O horizon of soils from Chichibu, Fuji and Chiba were derived from the Fukushima accident, and the 134Cs/137Cs ratio was constant among these research Forests. It showed a similar percentage contribution of contamination before the Fukushima accident. The mean contribution of the Fukushima accident to total contamination was roughly 88% in autumn 2011. This value decreased with time; 86% in 2012, 77% in 2013 and 65% in 2014. These results suggest that radiocesium released from the Fukushima accident moved relatively quickly out of the O horizon, whereas most the past residual 137Cs remained in the material cycle system on the soil surface. For example, 137Cs might have been sequestered inside mycorrhizal mycelia. However, it is far from a quantitative evaluation, because of the unstable occurrence of mushrooms between years and locations. In the A or C/O horizon, the mean ratio of Fukushima 137Cs to total 137Cs increased from 59% in 2011 to 73% in 2012, then decreased and stabilized at the equivalent level to the O horizon of about 65% in 2013 and 2014. The changes in the ratio appeared to be due to the transfer of 137Cs from the O horizon, and somewhat to the transfer out of the A horizon.

The proportion of pre-Fukushima 137Cs is high in mycorrhizal fungi, such as Suillus grevillea, S. luteus, S. viscidus, Amanita caesareoides, Lyophyllum shimeji and Lactarius laeticolor sampled in Fuji. Sugiyama et al. (2000) reported high 137Cs activities in P. lubrica and S. grevillei collected around Mt. Fuji in 1996. These fungal species can be characterized by their ability to retain radiocesium. Specifically, more than half the 137Cs was derived from pre-Fukushima fallout in S. grevillea, A. caesareoides and L. shimeji. Further, Catathelasma imperiale in Chiba had a low concentration of 137Cs, but the ratio of the pre-Fukushima 137Cs was also high. Thus, the range of radiocesium concentrations found in mycorrhizal fungi is large. It is unusual that the contribution of pre-Fukushima 137Cs fallout remained high under the influence of fallout from the Fukushima accident. The mechanisms remain unclear how fungi with a high turnover rate of cells and tissues can retain pre-Fukushima 137Cs, in which the ratio is much higher than in the soil substrate. 137Cs deposited over a few decades may continue to be circulated in a closed system of fungal mycelium, which prevents its loss to the lower soil horizons.

12.9 Conclusion

In this chapter, some of the dynamics of radiocesium contamination in the forest ecosystem in relation to mushrooms was revealed. Radiocesium accumulation in several mycorrhizal mushrooms was similar to that reported after the Chernobyl accident, but not all mushrooms were contaminated equally. Biology and ecology of mushrooms, geographical, geological and pedological features may affect radiocesium dynamics in forests. Monitoring data of radiocesium concentration could evaluate the transfer of radiocesium from the litter to the soil layer or mushrooms and will provide useful information on the mechanisms of radiocesium accumulation in relation to potassium, and the selective retention of absorbed radiocesium in mushrooms. The number of samples and period of monitoring, however, was insufficient. Long-term monitoring of 137Cs is necessary to clarify more precisely the dynamics of the contamination, though monitoring of 134Cs is now becoming difficult because of its short half-life.

Abbreviations

- Cs:

-

cesium

- DW:

-

dry weight

- FW:

-

fresh weight

- K:

-

potassium

- NPP:

-

nuclear power plant

- NWT:

-

nuclear weapons test

- TF:

-

transfer factor

- UTF:

-

the University of Tokyo Forest

References

Ban-nai T, Yoshida S, Muramatsu Y (1994) Cultivation experiments on uptake of radionuclides by mushrooms. Radioisotopes 43:77–82 (in Japanese with English Summary)

Borio R, Chiocchini S, Cicioni R, Esposti PD, Rongoni A, Sabatini P, Scampoli P, Antonini A, Salvadori P (1991) Uptake of radiocesium by mushrooms. Sci Total Environ 106:183–190

Brückmann A, Wolters V (1994) Microbial immobilization and recycling of 137Cs in the organic layers of forest ecosystems: relationship to environmental conditions, humification and invertebrate. Sci Total Environ 157:249–256

Byrne AR (1988) Radioactivity in fungi in Slovenia, Yugoslavia, following the Chernobyl accident. J Environ Radioact 6:177–183

Fielitz U, Klemt E, Strebl F, Tataruch F, Zibold G (2009) Seasonality of 137Cs in roe deer from Austria and Germany. J Environ Radioact 100:241–249

Guillitte O, Melin J, Wallberg L (1994) Biological pathways of radionuclides originating from the Chernobyl fallout in a boreal forest ecosystem. Sci Total Environ 157:207–215

Heinrich G (1992) Uptake and transfer factors of 137Cs by mushrooms. Radiat Environ Biophys 31:39–49

Igarashi S, Tomiyama T (1991) Radionuclide concentrations in mushrooms. Annu Rep Fukui Pref Inst Public Health 29:70–73 (In Japanese with English Summary)

Kammerer L, Hiersche L, Wirth E (1994) Uptake of radiocaesium by different species of mushrooms. J Environ Radioact 23:135–150

Kiefer P, Pröhl G, Müller G, Lindner G, Drissner J, Zibold G (1996) Factors affecting the transfer of radiocaesium from soil to roe deer in forest ecosystems of southern Germany. Sci Total Environ 192:49–61

Komamura M, Tsumura A, Yamaguchi N, Fujiwara H, Kihou N, Kodaira K (2006) Long-term monitoring and analysis of 90Sr and 137Cs concentrations in rice, wheat and soils in Japan from 1959 to 2000. Bull Natl Inst Agro Environ Sci No. 24-1-21 (In Japanese with English Summary)

Mascanzoni D (1987) Chernobyl’s challenge to the environment: a report from Sweden. Sci Total Environ 67:133–148

Minato S (2011) Distribution of dose rates due to fallout from the Fukushima Daiichi reactor accident. Radioisotopes 60:523–526

Muramatsu Y, Yoshida S (1997) Mushroom and radiocesium. Radioisotopes 46:450–463 (In Japanese)

Muramatsu Y, Yoshida S, Sumiya M (1991) Concentrations of radiocesium and potassium in basidiomycetes collected in Japan. Sci Total Environ 105:29–39

Pietrzak-Flis Z, Radwan I, Rosiak L, Wirth E (1996) Migration of 137Cs in soils and its transfer to mushrooms and vascular plants in mixed forest. Sci Total Environ 186:243–250

Rühm W, Steiner M, Kammerer L, Hiersche L, Wirth E (1998) Estimating future radiocaesium contamination of fungi on the basis of behaviour patterns derived from past instances of contamination. J Environ Radioact 39:129–147

Seeger R (1978) Kaliumgehalt höherer Pilze. Z Lebensm Unters Forsch 167:23–31

Shimizu M, Anzai I, Fukushi M, Nyuui Y (1997) A study on the prefectural distribution of radioactive cesium concentrations in dried Lentinula edodes. Radioisotopes 46:272–280 (In Japanese with English Summary)

Smith JT, Beresford NA (2005) Radioactive fallout and environmental transfers. In: Smith JT, Beresford NA (eds) Chernobyl – catastrophe and consequences. Springer, Berlin

Soil Survey Staff (2014) Keys to soil taxonomy, 12 edn. United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service

Steiner M, Linkov I, Yoshida S (2002) The role of fungi in the transfer and cycling of radionuclides in forest ecosystems. J Environ Radioact 58:217–241

Sugiyama H, Iwashima K, Shibata H (1990) Concentration and behavior of radiocesium in higher basidiomycetes in some Kanto and the Koshin districts, Japan. Radioisotopes 39:499–502 (In Japanese with English Summary)

Sugiyama H, Shibata H, Isomura K, Iwashima K (1994) Concentration of radiocesium in mushrooms and substrates in the sub-alpine forest of Mt. Fuji Japan. J Food Hyg Soc Jpn 35:13–22

Sugiyama H, Terada H, Isomura K, Tsukada H, Shibata H (1993) Radiocesium uptake mechanisms in wild and culture mushrooms. Radioisotopes 42:683–690 In Japanese with English Summary

Sugiyama H, Terada H, Shibata H, Morita Y, Kato F (2000) Radiocesium concentrations in wild mushrooms and characteristics of cesium accumulation by the edible mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). J Health Sci 46:370–375

Vinichuk MM, Johanson KJ (2003) Accumulation of 137Cs by fungal mycelium in forest ecosystems of Ukraine. J Environ Radioact 64:27–43

Vinichuk MM, Johanson KJ, Rosén K, Nilsson I (2005) Role of the fungal mycelium in the retention of radiocaesium in forest soils. J Environ Radioact 78:77–92

Yamada T (2013) Mushrooms: radioactive contamination of widespread mushrooms in Japan. In: Nakanishi TM, Tanoi K (eds) Agricultural implications of the Fukushima nuclear accident. Springer, Tokyo

Yamada T, Murakawa I, Saito T, Omura K, Takatoku K, Iguchi K, Inoue M, Saiki M, Saito H, Tsuji K, Tanoi K, Nakanishi TM (2013) Radiocesium accumulation in wild mushrooms from low-level contaminated area due to the Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear power plant accident – a case study in the University of Tokyo Forests. Radioisotopes 62:141–147 (In Japanese with English Summary)

Yamada T, Omura K, Saito T, Igarashi Y, Takatoku K, Saiki M, Murakawa I, Iguchi K, Inoue M, Saito H, Tsuji K, Kobayashi NI, Tanoi K, Nakanishi TM (2018) Radiocesium contamination of wild mushrooms collected from the University of Tokyo Forests over a six-year period (2011–2016) after the Fukushima nuclear accident. Misc Inf Univ Tokyo For 60:31–47

Yoshida S, Muramatsu Y (1994) Accumulation of radiocesium in basidiomycetes collected from Japanese forests. Sci Total Environ 157:197–205

Yoshida S, Muramatsu Y (1996) Environmental radiation pol1ution of fungi. Jpn J Mycol 37:25–30 (In Japanes with English Summary)

Yoshida S, Muramatsu Y, Ogawa M (1994) Radiocesium concentrations in mushrooms collected in Japan. J Environ Radioact 22:141–154

Zibold G, Drissner J, Kaminski S, Klemt E, Miller R (2001) Time-dependence of the radiocaesium contamination of roe deer: measurement and modeling. J Environ Radioact 55:5–27

Acknowledgments

I sincerely thank the staff of the University of Tokyo Forests for collecting and preparing the samples, and Drs. N. I. Kobayashi, K. Tanoi and T. M. Nakanishi for measuring the radioactivity in samples and for their valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Yamada, T. (2019). Radiocesium Dynamics in Wild Mushrooms During the First Five Years After the Fukushima Accident. In: Nakanishi, T., O`Brien, M., Tanoi, K. (eds) Agricultural Implications of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident (III). Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3218-0_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3218-0_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-3217-3

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-3218-0

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)

, Mushroom;

, Mushroom;  , O horizon;

, O horizon;  , A (C/O) horizon. 137Cs/40K ratio in Russula emetica was 6.9

, A (C/O) horizon. 137Cs/40K ratio in Russula emetica was 6.9