Abstract

Chinese citizens are becoming more conscious of their citizenship rights. As more and more Chinese citizens are involved in different stages of the decision-making process, this is changing how decisions are made. Citizen participation has led to more “scientific” policy decisions and better implementation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Chinese citizens are becoming more conscious of their citizenship rights. As more and more Chinese citizens are involved in different stages of the decision-making process, how decisions are made is changed in contemporary China. Citizen participation has led to more “scientific” policy decisions and better implementation.

In this chapter, we address citizen participatory action in public affairs and demonstrate its relation to policy change. We believe that Chinese citizen action has been one of the most significant forces propelling local policy change. This chapter includes four parts: the historical change of citizen participation, the controversial aspects of citizen participation, the status quo of institutionalized citizen participation, and the relationship between citizen participation and good governance.

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the study of China’s civil participation has been booming. Strong contributions have been made from scholars in public administration, political science, sociology, and other disciplines. Although the study of contemporary civil participation in China began by referring to modern Western democratic ideals, it is now heavily influenced by traditional Chinese ideas of “people-centered” governance. At its earliest stages, scholars focused on introducing Western democratic theories and research into Chinese academic discourse. Nowadays, scholars tend to concentrate on explaining a participatory phenomenon or practice with the help of the theories and putting forward suggestions for current local governance.

Classical civil participation mainly refers to citizen influence on government and policy through voting and other avenues. Methods were characterized as passive, indirect, voting, or representative. However, the 1960s brought the New Public Involvement movement to the United States and broadened the boundaries of civil participation, thus creating more extensive and varied connotations (Verba et al. 1978).

As the connotations of modern, civil participation expanded, Jia (2007) observed three effects. First, civil participation extends from election to decision-making and administration. In other words, public participation is an indispensable part of policymaking and the administrative process. Second, the scope of participation has expanded beyond government and policy. In this regard, citizens are also able to participate in the governance of those public affairs that are closely linked to their interests. Third, civil participation stresses civil society and citizenship consciousness, guaranteeing the active citizen involvement rather than passive participation.

As we see it, citizenship consciousness is the solid grounding of civil participation. Its prerequisite is active participation and a high level of involvement in public affairs (Young 2000). These actions help to legitimize the decision-making process and prioritize policies. Therefore, in this chapter, we use a perception of citizenship to discuss the development of, and obstacles facing, civil participation in China.

The most widely accepted framework of civil participation is Arnstein’s eight-rung ladder of participation. She sees citizen power as the very nature of civil participation and believes that different levels of participation indicate different degrees of citizen power. She classifies citizen power into three levels: Citizen Control, Tokenism, and Therapy and Manipulation. Only the actual establishment of an innate system of civil participation can guarantee sustainable citizen power. In turn, increasing citizen power can guarantee civil participation.

This chapter discusses the development path of citizen participation in China with reference to citizen power. In order to explore the currently existing, newly developing, and future forms and channels for increased civil involvement in China, we divide our discussion into four parts. We first outline the general development path in sequential order. We then discuss the most controversial topics of China’s civic participation in recent years. In the third part, we describe the status quo of civic participation in China. Finally, we explain the relationship between citizen participation and governance.

2 The Development Path of Civil Participation in Local China: An Historical Perspective

This section describes the historical view of the development of citizen participation in China and summarizes the development path in chronological order. In this history, 1980 is the pivotal year. Before 1980, the country was marked by totalitarian dominance and a centrally planned economy; after 1980, reforms ushered in an era of marketization and commercialization. Given these radical differences between before and after, the development of civic participation in China must be viewed within the correct historical context. Therefore, we attempt to illustrate the development path of civic participation through the telling of the many changes in China that represent a gradual progression toward citizen power.

2.1 The Era of the Planned Economy

Before the reform and opening-up policy of 1978, China had a planned economy. The country was governed as a totalitarian state, where an almighty government dominated all areas of society and the economy. Enterprises were owned by governments with different levels of ownership, and there was almost no private enterprise. Social services were embedded within the hierarchical administrative system and were involved and organized in people’s communes in rural areas and Danwei in urban areas. These two systems functioned as social resource distributors and were burdened with many social functions (Li and O’Brien 1996; Zhou and Yang 1999).

In local urban governance, residents were under rigid control of the Danwei system, one of the most important mechanisms for controlling participation in China. It was invented to dispel social uncertainty and collective protest through its strong resource mobilization, relative deprivation, and political process (Feng 2006). It actively prevented certain types of participation, such as violent protests or aggressive collective actions through the political effects of the Danwei system’s rigid hierarchy; citizen participation was strictly controlled (Liu 2000).

Walder (1983) suggested that the Danwei system had two ways to control individuals: organized dependence and principled particularism (Sun 1996; Bian 2010). In prereform China (before 1978), an urban resident’s social welfare services were provided mainly through their employment with a state-owned enterprise (commonly known as a work unit). Along with promises of lifelong employment, urban people had for the most part enjoyed secure lifetime medical and retirement benefits, housing, and education. Participants in the system were highly dependent on the state because it controlled all resources. This resulted in a vertical sanctuary-dependency relation. Horizontally, the Danwei system dissolved the organization of the society and created social segregation. This means citizens were reluctant to cooperate with others to achieve their common interests. Consequently, society lacked a horizontal social network to underpin collaboration among citizens, to say nothing of activism in public affairs (Putnam 2000).

Urban governance was also vertical and relied on a hierarchical district/subdistrict residents’ committee management system. Urban residents’ committees were established throughout the country beginning in 1958 and were designed to provide residential autonomy. However, in actual operation, the committees deviated from this purpose. The subdistricts became the representative organizations of the district government, and residents’ committee became the practical representative organization of the subdistrict. Residents’ committees were then extended to become extensions of government management, which also harnessed the willingness and ability of residents into participating in public affairs.

The situation in rural areas resembled those in urban China. People’s communes gathered all the resources available in their area and redistributed resources equally to each member. Members were led to participate in collective life according to people’s commune’s regulations, which limited the possibility of other collective activities.

In general, urban China’s administrative system resembled an upside-down pyramid. The upper government controlled almost all socioeconomic resources, made decisions, and pushed forward urban development in a “command–obedience” pattern. The participation mode at this time was state mobilization. The state mobilized citizens to participate in policymaking through its local branches. Citizens participated through a strictly controlled and limited channel and were guided to participate by the state. Needless to say, citizen power was quite low during this period. Limited access to civil participation added to state supremacy, further harming the subjectivity of citizens.

2.2 The Reform Era

After China embarked on its market-oriented reforms, large numbers of nonstate-owned enterprises were set up. Likewise, state-owned enterprises became more independent, market-oriented entities. These enterprises gradually broke away from the vertical administrative system, and a market system gradually took its place. Marketization led to the collapse of the “Unit Society” of the Danwei system, thereby breaking the link between workplace and residence in urban China. Work units were unburdened of their former social responsibilities, most importantly the responsibility to provide social security and housing (Cao and Chen 1997).

With economic reform and the collapse of the “Unit Society,” demands for autonomy for residents’ committees grew out of the expansion of social affairs. In 1989, the National People’s Congress enacted “The Law of the Residents’ Committee in People’s Republic of China,” which aimed to guarantee the autonomy of residents’ committees. Democratic elections and other deliberative institutions in urban areas transformed residents’ committees from government representatives to autonomic organizations. Since then, the local urban governance pattern has been shifting from a vertical administrative pattern toward a civil society-oriented horizontal pattern.

In rural China, with the collapse of the people’s communes in the late 1970s, the political structure of the village became institutionally hollow. People’s communes were quickly replaced by a grassroots autonomic organization—the villager committee. The villager committee concept was founded to fill the vacuum left by the dissolution of the people’s communes. However, what followed the free-to-tax reform in rural China was awakening of the link between the local government and grassroots autonomic organizations. Moreover, villager committees surpassed the residents’ committees in becoming relatively more autonomic and democratic institutions by holding direct elections that attracted broad participation. As a result, participatory democracy has been booming in rural China. Villagers have been effectively motivated to participate in public affairs and encouraged to discuss and debate during village deliberations.

Even though decentralization and marketization have weakened the power of the state at the local level, it is a mistake to interpret this as the state in retreat. In response to the broken link between the resident and workplace and between villager and commune, the Chinese government has filled the vacuum by strengthening its grassroots branches (Lin and Ma 2000). The state is still able to manage local affairs through grassroots government agencies, such as street offices (jiedaoban) and residents’ committees. This explains why residents’ committees still locate themselves inside the administrative “district–subdistrict–resident committee” system; its main function is to carry out government tasks. Therefore, even if grassroots autonomy is designed and stipulated by law, the level of autonomy is still under the control of the government. Participation in China remains politically sensitive and monitored and guided by formal institutions.

Nevertheless, compared to its planned economy years, China’s political environment has improved. Citizens have diverse avenues and free environments to participate. With marketization, and the awakening of modernity and subjectivity, China’s increasing occupational diversification, population mobility, and the improving quality of life, have led to an upsurge of diversified societal needs. However, the traditional vertical government system had already proven itself incapable of satisfying those needs. Thus, a new carrier—the social organization—was invented to take these expansive social functions under consideration after economic reform.

Social reform will be possible when large numbers of social organizations are built up. Social organizations have more resources, such as time, personnel, and budget, to solve different social problems and to deal with social affairs. As fast growing social forces, social organizations are crucial for better governance. They offer avenues for citizens to participate in various public affairs and their development helps cultivate a sense of citizenship in contemporary China.

To conclude, civil participation since China’s reform and opening-up now involves all aspects of social forces in both the traditional and the expanded sense, and is quite different from the pre-1980 totalitarian system that preceded it. First, the new pattern emphasizes plural social strengths and counters an almighty government. Second, China’s governance pattern has changed from the “command–obedience” model to a “consultative interaction” model. Third, forces from civil society have been awakened and emphasized in political discourses. Undoubtedly, China has made significant progress in promoting civil participation.

3 Controversial Topics in the Study of China’s Citizen Participation

Studies of China’s citizen participation are numerous. It is one of the most popular research themes in studies of China, and it attracts the attention of various scholars from different disciplines. Among many others, there are two burgeoning works on China’s citizen participation in recent years: contentious politics and deliberative democracy. These two topics represent the most popular noninstitutional participation avenue and institutional participation avenue, respectively. Moreover, they are miniature versions of the development of participatory citizenship. We introduce the political origins of these two studies and their current contributions toward a better understanding of citizen participation in China.

3.1 Contentious Politics in China

China’s contentious politics are the most studied research field of citizen participation for both foreign and domestic scholars. Contentious politics include social rebellion, social movements, collective actions, and other activities based on mass citizen mobilization. Unlike the previously mentioned village deliberation, this is a noninstitutionalized participation pathway, one that is widely taken by peasants and residents of both rural and urban China. Examples include homeowners’ protests, worker resistance, peasants’ resistance, appeals to higher authorities for help (shangfang), and the not in my backyard (NIMBY) movement; all of these mass actions are widely discussed and controversial political topics (Shi 2005; Chen 2006; Wang 2011; Zhang 2005; Cai et al. 2009; Pan et al. 2010; Cai 2008).

Many scholars have studied the peasant resistance movements in recent years (O’Brien 1996; O’Brien and Li 1999, 2006; Li and O’Brien 1999; Yu 2004; Ying 2001; Chen 2003; Li 2010; Cai 2006; Zhou 1993). The various reforms focused on rural China have generated numerous conflicts in society. For instance, the fiscal reform and the resulting financial burdens on peasants have led to the deprivation of rights and, thus, caused continual and widespread resistance. Li and O’Brien (1996) suggested that this type of resistance is characterized by both contention and participation. In other words, the resistance of peasants, which consists of demanding reasonable welfare, lower economic burdens, protection of collective assets, and transparency in their village’s public affairs indicates the awakening of civil rights in rural China.

It is also suggested that peasants are more likely to defend their rights following the logic of rightful resistance (struggle by law) when they feel deprived. Rightful resistance is a semi-institutionalized avenue of participation (Yu 2004). Among the many ways of rightful resistance, shangfang is still the most frequently used way for peasants to defend their legal rights. However, the practices of peasants have been given many new meanings as a result of their direct actions, such as the emerging subjectivity. Besides shangfang, advocacy, collective action, refusal to pay taxes and fees, and lawsuits are also common ways for peasants to resist what they believe to be unfair treatment. Despite the numerous disturbances this movement has inspired, thus far they have not seriously disrupted social order in China because most of these disturbances have been short-lived and nonviolent. They seldom use violence because doing so may justify a local government’s repression and increase citizen risk (Cai 2008).

Since the beginning of economic and social reforms in 1978, urban China has witnessed significant popular resistance from different groups of people. The impact of China’s reforms on community participation has generated great interest among scholars. Based on our understanding, the dynamics of resistance in urban areas should be understood in relation to the different reforms urban China has experienced. For instance, worker resistance was prevalent in the 1980s (Cai 2002). This could be attributed to the reform of state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which resulted in massive layoffs. This group of people felt deprived, so they organized to defend their rights collectively.

Nevertheless, the most typical citizen’s resistance in urban China in recent years is the collective action of households. The dissolution of employment units, housing commodification, and increasing labor mobility have forced the dissolution of Danwei communities and greatly strained kinship networks. The new concepts of community and community-based services were introduced and adopted in the mid-1980s; before then, community participation in China typically involved limited roles for community members in programs initiated by the government and led by the Communist Party (Bray 2006). Community members consequently lacked the necessary motivation and organizational infrastructure to participate in community decision-making processes or local politics.

As the housing commodification process deepened in the middle of the 1990s, a new community model, created by households living in commercial housing developments and organized according to geographical propinquity, has continued to emerge as an alternative to the prereform provision of social welfare and urban service delivery (Xu and Chow 2006). The new types of communities and the new community service programs require considerable involvement from local residents for financing services, strengthening the effectiveness of service delivery and meeting the increasing welfare needs of urban citizens (Ge and Li 2012).

In this new circumstance, residents become more willing to participate in community collective action to address their own community. This creates space for the numerous homeowners’ collective protests in recent years. Many scholars have been studying homeowners’ protests which entail many interesting stories about local participation (He 2005, 2007, 2013). These collective actions are their attempts to protect their living environment and assets, implicating their rights to live and own property.

The most aggressive actions of homeowners may be the NIMBY movement organized to prevent polluting facilities from being locally established. As an emerging social phenomenon, homeowners’ protests are the structural products of urbanization and housing commodification. They bring with them the opportunity to overturn residential indifference to local governance. People are more inclined to participate in the communities where they live.

The numerous disturbances of these direct actions have thus far not seriously disrupted the social order in China because most of these disturbances have been short-lived and nonviolent. None of these contentious political actions are antiauthoritarian but rather provide a pathway for citizens to achieve civil rights. These protests are all territorialized and organized in pursuing proper rights, during which citizenship consciousness is also cultivated. Citizenship is achieved through the protection of their civil rights; in this case, their right to own property. But it is also achieved through the practice of their political rights. Therefore, contentious politics are a way for Chinese citizens to realize their citizenship.

3.2 Democratic Deliberation in China

As more and more people defend their rights through the noninstitutionalized pathways, such as resistance, protest, and rebellion, the government is making great efforts to establish institutionalized participation pathways at the same time to reduce social protest and strengthen the government’s ruling capacities. It is believed that people choose a noninstitutionalized pathway because they believe they are being ignored. As more and more citizens became eager for the chance to voice their preferences and express their opinions, democratic deliberation that fits in the socialist tradition of political participation was introduced to both rural and urban China in the early 1990s (He 2004).

Democratic deliberation aims to inspire the masses to exert influence on policymaking through public discussion. Deliberation is formal discussion and debate with the purpose of producing thoughtful, reasonable, and well-informed public opinions (Davies and Chandler 2011). Many deliberative, participatory, and consultative institutions have been established in China, such as the consultative and deliberative meetings, citizen evaluation meetings, consensus conferences, urban and village representative assemblies, citizen forums, public hearing, and so on. The Chinese consultative meeting or public hearing is designed to get people’s support for local projects and to be a forum for people’s opinions. The popular conciliation or mediation meeting is designed to solve various local problems and conflicts. As we see it, these deliberative avenues are created to dispel the social protests through institutional design, such as equal discussion, open access, reason-giving, and other-regarding (Cohen 1997; Young 2000; Dahlberg 2004; Habermas 2006).

In recent years, deliberative democracy has become increasingly significant. The Chinese government has made democratizing public decision-making through deliberation more of a priority, because legitimacy can be boosted through opinion formation based on collective deliberation. In the recently hosted 19th China’s National People’s Congress, President Xi has raised its profile even further. Since first being mentioned in the 18th China’s National People’s Congress, deliberative democracy has been highly emphasized ever since, which is as significant as democratic election and democratic decision-making. Current discussions of deliberative democracy in China are cutting edge issues and meaningful in explaining the development of Chinese citizen participation. As deliberative democracy gradually increases in scope, it is becoming unavoidable in China. Introducing deliberative democracy incrementally can facilitate China’s democratization process; it enables the Chinese people to adjust themselves to democracy and learn it gradually (Zhou 2012).

Many scholars have captured this rising trend in their studies of deliberative participation in China. Professor Baogang He is the most outstanding one. He is dedicated to the study of deliberative institutional experiments in rural China. There have been various forms of experimental deliberation at the local level in China, including public hearings, mediation meetings, and deliberative polling. He and Thøgersen (2010) studied one of the most famous pioneering experiments—the deliberative poll in Zeguo Town, Zhejiang Province. In their study, not only did the poll incorporate the ideals of deliberative democracy theory, such as inclusiveness and equality, but it also showed that deliberative democracy does exist in China, a place where deliberative democracy was thought to be unlikely to happen (Fishkin et al. 2010).

The establishment of participatory and deliberative institutions, such as village representative assemblies, has changed the structure of village politics in China. During those assemblies, meetings, hearings, and forums, major decisions on village affairs such as village collective assets and budgets are discussed, debated, and deliberated upon by village representatives. Villagers are willing to participate since being involved in the decision-making process can guarantee them the empowered status that will allow them to protect their own interests. It seems that there is a tendency for the village democratic process to shift from village election to village deliberation (He 2014). The transformation of village politics is worth further, careful study. On the other side, local urban communities have also developed a number of new participatory and deliberative institutions. However, village deliberation has received more attention because it has made greater progress and become transformative.

4 The Status Quo of Legal Citizen Participation in China: A Critical Perspective

In the previous section, we suggested that the noninstitutionalized avenues of participation have been frequently chosen by underprivileged citizens. This phenomenon aroused our attention because if there were better alternatives, they would have resolved their problems within the legal system as contentious politics are always time consuming and sophisticated. So why is legal participation so much more difficult than the contentious options? Why are so many citizens defending their rights through collective action? In answering these questions, we clarify the legalized democratic participation system in China and conclude scholars’ criticisms towards current system.

4.1 Overall Description on the Institutionalized Participation Avenues in China

Currently, the four major, legal democratic institutions are: the system of people’s congresses, the Chinese political party system, the system of national regional autonomy, and the system of self-governance at the grassroots level. Apart from these, citizens also have many other political rights, such as freedom of speech, association, assembly, and procession. These political rights are all stipulated in the Chinese constitution. Given all this, how do we comprehend the legal political participation rights of Chinese citizens in terms of these regulations?

First, four democratic institutions legalize the civil rights of citizens to participate in the decision-making processes. They are the people’s congress system, the national regional autonomy system, the system of multiparty cooperation and political consultations, and the system of grassroots autonomy. The system of people’s congress undertakes representative democracy. Members are representatives elected by citizens to express their voices. People’s congresses at all levels are meant to involve civic participation in the decision-making process. The system of multiparty cooperation and political consultations gives citizens the freedom to choose to join an approved political party. Parties may express their opinions and influence decision-making through participating in the Chinese people’s political consultative conference. After deliberation, opinions from different parties will be seriously considered by the governing party. As for the Chinese grassroots autonomy system, it is meant to be a retreat of state power from local governance. Space is left for residents or villagers to decide their own public affairs through various activities, such as public hearing, deliberative polling, and democratic meeting.

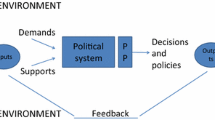

Second, citizens can exercise their civil rights and participate in public affairs to pursue their common interests through joining political parties, associations, or assemblies. In addition, participation includes public supervision of public sectors by civil society. This is a legal avenue of participation. However, it is not intended to change decision-making or pursue public interests. It is meant instead to be an appeal for responsible officials and just governance. The structure of the legal participation institutions is displayed in Fig. 19.1.

4.2 The Existing Problems of the Legal Participation Avenues

Chinese scholars have suggested, and widely discussed, three main problems with institutionalized participation in China today: the representation in local people’s congress (LPC), the mobilization of grassroots China, and the reform of the social organization system.

First, the representation of LPC. Limited civil participation adds to state supremacy. Representation provides a better breeding ground for meaningful citizen participation. As is well known, the LPC is a democratic institution, carrying out legislative activities and practicing supervision on public organizations through public participation. O’Brien (2009) suggests that the increasing role of LPCs in lawmaking and supervising governmental organizations “has less to do with responsiveness and changing state-society relations and more to do with state-building, restructuring bureaucratic ties, and making Party rule predictable and effective.” Nevertheless, there are supposedly three major roles for the LPCs. Apart from lawmaking and oversight, representation constitutes another significant function of the LPC. However, the reality is that it functions selectively. It emphasizes scientific decision-making and oversight rather than representation of public interests. Little attention is devoted to elections, deputy-constituent ties, and speaking out at plenary sessions (O’Brien 2009).

A representative government requires institutional machinery to allow constituents to express their wishes (Hanna 1967). In today’s China, the linkage between popular preferences, deputy behavior, and policymaking is tenuous. Local leaders retain a tight grip on LPC elections and there is “minimal electoral connection between the elected and those who elect them” (Xia 2007). The LPC selection system has been criticized for unequally incorporating various social groups into lawmaking and a few underprivileged groups are lumped together with a far larger number of elite groups. This unequal access to the LPC negates the function of the LPC in this area because the interests of society, as a whole, are not reliably taken into account.

Some deputies in higher-level congresses are not even aware of being candidates of LPC until they read about their “election” in the newspaper (Brantly 1982). Many members regard selection as a favor that should be repaid by agreeability rather than by the spirited advocacy of constituent interests (Derleth and Koldyk 2012). LPCs have become places where two interests intersect: the “central” interests represented by the local Communist party committee and the “local” interests represented by the local people’s congress delegates. Nevertheless, the state still penetrates into and controls LPCs. As Manion (2008) concluded: “Congresses acted as ‘rubber stamps,’ ineffectual in the face of powerful Party committees, as well as government institutions.”

As a matter of fact, in contemporary grassroots China, delegates of LPCs are required to set up hotlines and reception days and to hold regular meetings with constituents to listen to their opinions. Through these channels, deputies learn of and address requests of the public. Consequently, the electoral ties are becoming closer and public discontents and concerns are being aired. However, the reasons for holding these events are to uncover social discontent and sound an alarm before an explosion occurs (Cho 2008).

To conclude, without institutional mechanisms to ensure it, representation rests on public-spirited members and leadership forbearance and, in a fundamentally unrepresentative system, is precarious, inexact, and occasional.

Second, mobilization of grassroots China. Since the reform and opening-up, urban reform overturned the system that aimed to fix citizens in their Danwei and their specific living places. Rural reform released peasants from their lands in the villages, which facilitated the rural to urban migration. With the collapse of the Danwei system and deepening urbanization, individuals were given larger mobility, including occupational mobility, geographical mobility, and social mobility.

Under these circumstances, a large number of peasants flooded into cities and the number of citizens migrating from cities to cities also surged. Consequently, in order to expand the coverage of grassroots public service, many villages were annexed or withdrawn so as to create a larger administrative village. At the same time, urban areas also promoted the annexation of residents’ committees in order to create larger community committees. Obviously, in both urban and rural China, the grassroots autonomic organizations are integrated and condensed. Each grassroots autonomic organization is expected to cover a large geographical area. However, the expanded scope of governance weakened the ties between the committee and the villagers or residents, which also weakened the autonomic organizations’ abilities to mobilize and manage public affairs.

Moreover, housing commercialization made housing a product and promoted buying and selling behaviors in the housing market. Thus, residents in a community have higher mobility, and society has shifted from an acquaintance society to a stranger society (Li 2013). Communities are fragmented, comprising many separate cells. Hence, residents become indifferent to public affairs and are reluctant to participate in pursuit of public interests. It seems that after the dissolution of the Danwei, grassroots China still lacks a regime to mobilize residents and promote community participation.

Finally, there has been an administrative involution of grassroots self-governance (Hu 2005; He 2004). Residents’ committees and villager committees are still governmental branches extended into grassroots governance. They are still under the command of Jiedaoban, the detached office of the administrative authorities. The essence of autonomy has not yet been put in the right place. Hence, involution results in less citizen participation in grassroots autonomic governance because the public is aware that they are not yet the masters of local affairs. Hence, more and more homeowners and villagers choose to take part in collective actions to achieve their requirements. All these have made the mobilization in grassroots China an urgent but tough task for current authorities.

Third, reform of the social organization system. Not until the 6th Plenary Session of the 16th CPC Central Committee in 2006 was the concept of “social group” officially suggested, thus making the reform of the social organization system both a politically and academically significant topic. Alongside China’s reform and opening-up, the central government has realized that society is actually an important partner in improving governance. In response, the government has instituted a system of legal registration to manage, and hopefully control, Chinese social organizations. Following the government’s rhetorical appeal for “small state, big society,” the registration thresholds and conditions have been lessened in order to promote the development of social organizations to fill gaps left by the retreat of government. Nongovernmental organizations broadened in both number and scope right after the policies were loosened. Compared to government, social organizations are the better organizations to offer public services because they are closer to the public, have lower operating costs, and are more capable of providing diversified services that citizens actually want.

The development of social organizations could advance social empowerment and reshape the state-society relationship so as to achieve better governance. However, the common difficulty faced by social organizations is that they still depend on governments in a noninstitutional way. Ge and Li (2012) suggested that even though Chinese social organizations have a certain degree of autonomy, they are still dependent on the government in informal ways, for instance, fund-raising, goal setting, and leader selection.

First, governments at different levels could help social organizations through indirect financial support, such as by offering free offices or human resources and by paying for part of staff salaries. Apart from this, government could also help social organizations to set up relations with enterprises so that enterprises could donate and sponsor the activities of these social organizations.

Second, social organizations are encouraged by the government because they are expected to fill in the gaps left by governmental functional transformation in China. Therefore, before a social organization matures, it is given a specific goal that meets the managerial needs of the government. Governments have taken a significant role in the birth, operation, and development of social organizations.

Third, the Chinese government will also dispatch the “appropriate” people into relatively large social organizations. These people are closely related to government officials and familiar with government affairs, thus making them the representatives of the governments’ intentions in the social sector. By helping social organizations take over the transferred functions and exerting influence on their daily operations, governments become the actual leader of the social organizations (Tang and Ma 2011).

In recent decades, China has made important progress in promoting civil participation. However, participation in China remains politically sensitive and is monitored and guided by formal institutions. Admittedly, social organizations are facing a more flexible policy environment with lower registration thresholds and more preferential policies. However, the leading role of the government has never faded away in the social sector. Social organizations in China are prone to depending on government rather than making decisions on their own. Hence, their participation in public affairs is actually restricted by many factors, for instance, limited funds and resources, lack of networks, and coercive appointments.

5 Citizen Action and Good Governance

The last part of this chapter describes citizen action in China, as well as its relationship to good governance. Chinese governments have long realized that they urgently need to boost their legitimacy by improving their relationship with citizens, and they have made great efforts to promote deliberative participation at local levels. Chinese citizens have more options now than at any time previously to express their demands.

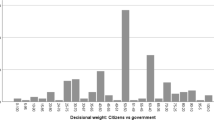

As shown in Fig. 19.2, using Arnstein’s eight-rung ladder for levels of participation and Plummer and Taylor’s (2004) ladder of community participation in China (left side) as a guide, we have reinterpreted these models in order to account for China’s local participation context (right side). Our model takes into consideration Chinese characteristics and displays the different levels of participation in local China.

However, as was demonstrated in the previous section, the effect of institutionalized participation avenues on promoting citizen participation is still much less than expected.

Even though governments at all levels encourage liberal and legal participation through various supportive policies, they still control citizen participation. The most common way of managing and controlling it is exerting influence in noninstitutionalized ways. Examples include appointing people for certain positions, offering financial support, informing a narrower group of people deliberately or making the participatory procedures unduly complex. These noninstitutional interferences harness both the scope and quality of citizen participation in China.

For another, as many scholars have argued, the avenues for legal participation in China are designed as specific mechanisms to co-opt and manage key players. Institutions such as LPCs are merely a tool of cooptation by the authoritarian regime, through which social discontent could be dissolved within the institutional routine without destroying the social harmony and threatening governmental authority.

O’Brien (2009) argued that the institutionalization of the people’s congress system did not bring liberalization, but instead brought rationalization and inclusion. Rationalization helped improve one-party rule by “legalizing political power and circumscribing the authority of individual leaders.” Inclusion helped the regime to “preempt political challenges and protect party rule” by expanding the regime’s influence on various forces in the society and the market.

Rationalization and inclusion have severely limited the effect of citizen participation as a way for normal citizens to promote policy change. This explains why there are more and more people choosing to fight for their rights through collective actions or even violent protests. This disorder in society is clearly the result of a lack of effective and efficient legal participation avenues and the misplacement of government in the state-society relationship. Furthermore, the theory of citizenship acknowledges that the public has the right to be proactively involved in a meaningful way in the decision-making process rather than being part of empty ritual participation. Governments are supposed to help citizens to express themselves rather than control and direct policy changes. Therefore, promoting authentic and effective citizen participation is crucial for the Chinese government in its pursuit of good governance and building a harmonious society.

As Arnstein (1969, p. 216) stated, as society becomes more complex and modernized, and people become more citizenship conscious, authentic participation will become a requirement for successful implementation of government policies. In considering good governance, decision-making processes are required to be participatory, consensus oriented, accountable, transparent, responsive, equitable and inclusive, effective and efficient, and obedient to the rule of law. Participation is highly emphasized in the good governance model (see Fig. 19.3). It is assumed that a society moving up Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation is progressing toward a better governance (Enserink and Koppenjan 2007). Citizen participation is considered to be the cornerstone of good governance (Enserink et al. 2007). It is the process through which citizens and stakeholders influence and share control over priority setting, policymaking, resource allocations, and access to public goods and services (World Bank Group 2005). Empty, ritualized participation will no longer be accepted by China’s awakening citizens. Determining how to involve citizens in the decision-making process is now the crucial question for reaching good governance.

The eight dimensions of good governance (UNESCAP 2005)

Based on our understanding, Chinese citizen participation should not be merely regarded as a mechanism to promote efficient decision-making, nor should it be merely regarded as a channel to convey public opinions. Instead, citizen participation is also practiced as a form of citizenship consciousness in which consensus is achieved through debates and deliberations (He 2016). The Chinese government should optimize its participation institutions, enlarge participatory access, and make citizens better informed before the decision-making process begins. At the same time, society must be empowered and government must retreat thoroughly from specific sectors and play the role of ombudsmen instead of taking the lead in local governance.

References

Arnstein, S. 1969. A ladder of public participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35(4), July, 216–224.

Bian, Yanjie. 2010. Relational sociology and other cognate discipline (Guanxi Shehuixue Ji Qi Xueke Diwei).

Brantly Womack. March 1982. The 1980 County-Level Elections in China: Experiment in Democratic Modernization. Asian Survey 22(3): 261–277.

Bray, D. 2006. Building ‘community’: New strategies of governance in urban China. Economy and Society 35(4): 530–549.

Cai, Y. 2002. Relaxing the constraints from above: Politics of privatizing public enterprises in China. Asian Journal of Political Science (10): 94–121.

Cai, Y. 2006. State and Laid Off Workers in reform China. London: Routledge.

Cai, Y. 2008. Power structures and regime resilience: contentious politics in China. British Journal of Political Science 38(3): 411–432.

Cai, H., Chaohai Li, and Jianhua Feng. 2009. The collective action of migrant workers—based on the research on enterprises in Pearl River Delta (Liyi Shousun Nongmingong Liyi Kangzheng Xingwei Yanjiu—Jiyu Zhusanjiao Qiye de Diaocha). Journal of Sociology Study (1).

Cao, J., and Z. Chen. 1997. Stepping Outside the Ideal Castle: Research on the Unit in China (Zou Chu Li Xiang Cheng Bao: Zhong Guo Dan Wei Xian Xiang Yan Jiu). Shenzhen: Haitian Press.

Chen, Feng. 2003. Between the state and labour: The conflict of Chinese trade unions’ double identity in market reform. The China Quarterly 176.

Chen, Yinfang. 2006. Action power and institutional limitation—the middle level in urban movement (Xingdongli Yu Zhidu Xianzhi—Dushi Yundong de Zhongchan Jieji). Journal of Sociology Study (4).

Cho, Y.N. 2008. Local People’s Congresses in China: Development and Transition. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, J. 1997. Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 67–91.

Dahlberg, L. 2004. Net-public sphere research: Beyond the first phase. The Public 11(1): 27–77, 2004, 29–30.

Davies, T., and R. Chandler. 2011. Online Deliberation Design: Choices, Criteria, and Evidence. In: Democracy in Motion: Evaluating the Practice and Impact of Deliberative Civic Engagement. Oxford University Press.

Derleth, J., and Koldyk, D.R. 2002. The district people’s congresses and political reform in China. Problems of Post Communism 49(2).

Enserink, B., and J. Koppenjan. 2007. Public participation in China: sustainable urbanization and governance. Management of Environmental Quality: An International Journal 18(4): 459–474.

Enserink, B., M. Patel, N. Kranz, and J. Maestu. 2007. Cultural factors as co-determinants of participation in river basin management. Ecology and Society 12(2): 24. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss2/art24/.

Feng, S. 2006. Danwei segregation and collective contention (Dan Wei Fen Ge Yu Ji Ti Kang Zheng). Journal of Sociology Study (3): 98–134.

Fishkin, J., Baogang He, Robert C. Luskin, and Alice Siu. 2010. Deliberative democracy in an unlikely place: Deliberative polling in China. British Journal of Political Science 40(2): 435–444.

Habermas, J. 2006. Towards a United States of Europe. Translated excerpt from Bruno Kreisky Prize Lecture. March 9. Available at: http://www.signandsight.com/features/676.html.

Hanna F. Pitkin. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 221–223.

He, B. 2004. Participatory and Deliberative Institutions in China. In: Collection of the Essays Presented at the International Conference on Deliberative Democracy and Chinese Practice of Participatory and Deliberative Institutions. Zhongguo she hui ke xue chu ban she. Beijing, China, pp. 92–108.

He, Y. 2004. The involution of Chinese urban grassroots autonomic organizations and its formation (Zhongguo Chengshi Jiceng Zizhi Zuzhi de Neijuanhua jiqi Chengyin). Journal of Sun Yat-sen University (2).

He, B. 2007. Rural Democracy in China. New York: Palgrave/Macmillan, pp. 96–97.

He, B. 2014. From village election to village deliberation in rural China: Case study of a deliberative democracy experiment. Journal of Chinese Political Science/Association of Chinese Political Studies 19: 133–150.

He, Y. 2016. Revolution without change: The limitation of Chinese local administrative reform (Wu Biange De Biange: Zhongguo Difang Xingzheng Gaige De Xiandu). Journal of Xuehai (1): 34–43.

He, B., and S. Thøgersen. 2010. Giving the people a voice? Experiments with consultative authoritarian institutions in China. Journal of Contemporary China 19(66): 675–692.

Hu, W. 2005. The reform and reflection on the urban grassroots autonomy institution since late 1990s (20 Shiji 90 Niandai Houqi Yilai Chengshi Jiceng Zizhi Zhidu de Biange yu Fansi). Journal of Wuhan University (3).

Jia, X. 2007. An analysis of NGO Avenues for civil participation in China. Social Sciences in China. Special issues NGOs and social transition in China.

Li, L. 2010. Rights consciousness and rules consciousness in contemporary China. The China Journal 64.

Li, P. 2013. The reform and future of social organization system (Woguo Shehui Zuzhi Tizhi de Gaige he Weilai). Journal of Sociology (2).

Li, L., and K.J. O’Brien. 1996. Villagers and popular resistance in contemporary China. Modern China 22(1).

Li, L. and K.J. O’Brien. 1999. The Struggle over Village Elections: The Paradox of China’s Post-Mao Reforms. Harvard University Press, pp. 129–144, 382–389.

Lin, S., and Y. Ma. 2000. Community Organization and Residents Committee Construction (She Qu Zu Zhi Yu Ju Wei Hui Jian She). Shanghai: Shanghai University Press.

Liu, J. 2000. Unit China: Individual, Organization and Government During Social Reconstruction (Dan Wei Zhong Guo: She Hui Tiao Kong Ti Xi Chong Gou Zhong De Ge Ren, Zu Zhi He Guo Jia). Taijin: Renmin Press.

O’Brien, K.J., and L. Li. 2006. Rightful Resistance in Rural China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Brien, K. 1996. Rightful resistance. World Politics 49: 31–55.

O’Brien, K., and L. Li. 1999. Selective policy implementation in rural China. Comparative Politics 31: 167–186.

Pan, Y., H. Lu, and H. Zhang. 2010. The formalization of social class: The labor control and collective contention. Open Times (5).

Plummer, J., and J.G. Taylor. 2004. The characteristics of community participation in China. In: J. Plummer and J.G. Taylor (eds), Community Participation in China, Issues and Processes for Capacity Building. London/Sterling, VA: Earthscan.

Putnam, R.D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Shi, F. 2005. Relation network, rightful contention and contemporary urban collective action in China (Guanxi Wangluo, Yi Fa Kangzheng He Zhongguo Chengshi Jiti Xingdong). Journal of Xuehai (3):1–27.

Sun Liping. 1996. Relation, social network and social structure (Guanxi, Shehui Guanxi yu Shehui Jiegou). Journal of sociology study (5):20–30.

Tang, W., and X. Ma. 2011. Non-political autonomy: Non-governmental organization’s living strategy. Zhejiang Social Sciences (10).

UNESCAP. 2005. What is good governance? United Nations economic and social omission for Asia and the Pacific. Available at: http://www.unescap.org/pdd/prs/ProjectActivities/Ongoing/gg/governance.asp.

Verba, S., N. Nie, and K. Jae-on. 1978. Participation and Political Equality: A Seven Nation Comparison. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, pp. 51–52.

Walder. 1983. Organized dependency and cultures of authority in Chinese industry. Journal of Asian studies 18(1).

Wang, J. 2011. Internet mobilization and collective contention of OEM workers (Hulianwang Yu Daigongchang Gongren Jiti Kangzheng). Open Times (11): 114–128.

World Bank Group. 2005. “Poverty reduction, strategy formulation organizing participatory processes in the PRSP. What is participation and what role can it play in the PRSP?” Available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTPCENG/1143240-1116506251485/20508873/Organizing+Partcipatory+Processes.pdf (accessed Jan 2012).

Xia, M. 2007. The People’s Congresses and Governance in China: Toward a Network Mode of Governance. London: Routledge.

Xu, Q., and J. Chow. 2006. Urban community in China: Service, participation, and development. International Journal of Social Welfare 15(3): 198–208.

Ying, X. 2001. Dahe Yimin Shangfang de Gushi (A Story of Migrants’ Appeals in Dahe). Beijing: Sanlian Shudian.

Young, I.M. 2000. Inclusion and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yu, J. 2004. An explanation on peasants’ collective action. Journal of Sociology (2).

Zhang, L. 2005. Homeowners’ collective action: The motivation and mobilisation. Journal of Sociology Study (6):1–39.

Zhou, X. 1993. Unorganized interests and collective action in Communist China. American Sociological Review 58(1).

Zhou, W. 2012. In search of deliberative democracy in China. Journal of Public Deliberation 8(1).

Zhou, Y., and X. Yang. 1999. Unit Institution in China (Zhong Guo Dan Wei Zhi Du). Beijing: Chinese Economy Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

He, Y. (2019). Citizen Action and Policy Change. In: Yu, J., Guo, S. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Local Governance in Contemporary China. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-2799-5_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-2799-5_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-13-2798-8

Online ISBN: 978-981-13-2799-5

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)