Abstract

This chapter addresses some of the key issues and weaknesses in the field of migration, arising out of inconsistent methodology, issues that need addressing if the field is ever to advance as the field of fertility has so much over the past 50 years. Part of this advance depends on collecting much more, better, and more comparable data on both internal and international migration. This requires our arriving at a common, generally accepted definition of migration based only on a change in usual residence involving crossing a recognized administrative boundary. This will distinguish it from other forms of mobility. In addition, data collection techniques for collecting data on migrants from specialized migration surveys should recognize that migrants (especially recent ones, which are generally of greatest interest for both research and policy) are usually rare elements, so specialized sampling methods first developed by Kish and others should be used, using stratified disproportionate sampling. The overall design of the survey questionnaire is discussed, focused onthe last move approach or the event history approach. Finally, the chapter also mentions some other key methodological matters, including the need to use appropriate comparison groups to study the determinants/consequences of migration; to compare migration intentions with actual decisions; to consider contextual effects and the possiblevalue of Big Data. A number of recent experiences in collecting migration data are reviewed and assessed in the course of the chapter as relevant, and the issue of a world migration survey is raised.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution.

Buying options

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Learn about institutional subscriptionsNotes

- 1.

White and Lindstrom (2005) cite the finding of Rees et al. (1996) that the range of rates of net migration for administrative units of the EU is triple the range of rates of natural increase .

- 2.

See press release of World Bank (April 11, 2014.) See also the chapter in this volume by J.E. Taylor and Michael Castelhano.

- 3.

Most countries use two levels of political or administrative subdivision to administer the country at sub-national levels, regardless of geographic size or population size, though a few use three levels, such as Indonesia (Provinces, Kabupaten, Kecamatan).

- 4.

See many standard textbooks in demography, notably Siegel and Swanson (2004, pp. 455ff, 463 and 493ff.). In addition, the United Nations Statistical Office has sought for years to promote common usage across countries (see UN 1949, 1972, 1998, UN Forthcoming).

- 5.

The peculiar case of China is noteworthy here. Thus for decades under Chairman Mao, the government used the Hukou system (tying access to a residence , employment, free schooling , subsidized rice, etc.), to control the place of residence of the population and hence limit migration. Even with the “opening” of the economy to capitalism under Deng Tsao-ping in the 1980s, the Hukou system continued, but was overwhelmed by the approximately 250 million people reported to have moved from rural to urban areas for employment in the past three decades, perhaps the largest migration in such a time period in human history. Vast numbers of this “floating population” continue to maintain their legal residence and Hukou in their village , where often a parent continues to live and keep the plots of land and raise the grandchild (child of the migrant). The grandparent often refers to the migrant as a continuing member of the household , and therefore a non-migrant. But in fact, that person, who may have lived away in a city for decades or has just left days ago, has in essence changed his/her place of residence, and is therefore definitely a migrant, using the recommended dual criteria. While some migrants may not have originally intended to move long-term to the city, they did so, de facto.

- 6.

This situation is commonly confronted by interviewers: E.g., an editor of this volume reports this to be the case in the new Demographic Surveillance Systems in Africa (White 2014).

- 7.

The UN (2008) also recommends obtaining duration of residence , especially for internal migration, plus place of previous residence. This indeed provides more complete data, but is more complex to tabulate and interpret, and does not provide a population estimate for any specific year in the past.

- 8.

Nevertheless, censuses and surveys not focusing on migration nowadays often utilize questions of type (2) under the illusion that they are economizing on questions. This is a false economy, however, and all too common when people aim to collect as much data as possible with as few numbered questions as possible, and thereby fail to use initial, additional simple screening questions that ensure a facile flow of the interview , to the benefit of both the respondent and the interviewer.

- 9.

Exceptions occur when the survey interview can be conducted in places of origin when the migrants are themselves visiting their home communities. This is often the case at the time of the Spring Festival in China and other Asian countries, and at Christmas in many Western countries.

- 10.

Thus the European Union , after lengthy deliberations, adopted a definition of emigrant as someone who has been away in another country for at least 12 months (EU 2007).

- 11.

Personal discussions with officials of the Direction de la Statistique, March 23–27, 2013, and mentioned in Bilsborrow (2013).

- 12.

The MPI reported, based on surveys in 2011–2012, that 381 million persons moved in the previous five years within their country, including 196 million women and 185 million men (September 23, 2013). This is over 5 % of the world population, but includes all changes of residence including those not involving crossing a recognized administrative border . See also Bell and Muhidin (2009).

- 13.

Based on conversations with ILO -STAT officials in Geneva in May 2007.

- 14.

- 15.

With their wealth of data on fertility , DHS surveys can be used to study relationships between internal migration and fertility (Chattopadhyay et al. 2006). The use of a 6-year monthly calendar to record major events including births and changes of residence is also illustrated based on the 2006 experimental Peru DHS survey (Moreno et al. 1989). See also discussion of calendars in section “Some special methodological issues related to migration data collection” below.

- 16.

Other multi-country surveys that could be discussed in this context include UNICEF’s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) , which focus on children, and the Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) , a European-wide survey of 5,000–6,000 households focusing on poverty and employment, but thus far collecting nothing on migration. However, the fact that the latter have income data makes then potentially good candidates for adding questions on migration, except for small sample sizes. Many of the CIS states conduct Household Budget Surveys, with the same positive and negative possibilities. The MICS surveys could be modified to include migration to study child migration, and are likely being used for that purpose now, with increasing interest in independent child migration and trafficking.

- 17.

This discussion draws on Bilsborrow et al. (1997, Chapter 6B).

- 18.

Thus studies of the determinants and/or consequences of migration from each of those five (vs. two) countries to Italy could have been implemented, permitting more fascinating comparisons of not only the most basic data on how migrants from different countries differed, but how the determinants of migration differed from one country of O to Italy (which would lead to the research question, why?), and how the consequences of migrants from the countries of O differed from one to another, and for migrants to Italy vs. Spain , and why. But these comparative analyses have yet to be carried out (data continue to be available at NIDI and from the countries that make this possible, but apparently no one is funding it). See also more details in section “Some special examples of migration surveys” below.

- 19.

Additional examples and extensions to more regions or more countries are found in Bilsborrow et al. (1997).

- 20.

Given the natural inclination of people to better recall more recent events, the relevant reference time is likely less than the mean time in the interval, e.g., 2 or 4 years, respectively, before the interview .

- 21.

In the absence of any data on migrants, or even data on population from a recent census, there may yet be another alternative, to select regions/areas based on “expert” or informed judgment, that is, people knowledgeable about where emigrants mostly originate from. This could be used to stratify areas roughly according to the expected intensity of emigration , then oversample those regions or PSUs with high expected proportions of emigrants compared to areas with less migration intensity. This was done in several NIDI countries (see section on “Some special examples of migration surveys” below).

- 22.

C.f. many papers on RDS presented at the International Conference on Methods for Surveying and Enumerating Hard to Reach [H2R] Populations, organized by the American Statistical Association (New Orleans, Oct. 31–Nov. 3, 2012).

- 23.

“2014 FNNR Socioeconomic, Migration and Environment Household Survey”, Li An, Dept. of Geography, San Diego State University, Principal Investigator (funded by US National Science Foundation).

- 24.

An interesting study (with analogy to the famous Kurosawa movie, “Rashomon”), is Akee and Kapur (2012).

- 25.

E.g., see study of effects of remittances from male household members working abroad on children’s education back home, by gender (Assaad 2010).

- 26.

Yang (1994) in a study of migrant adjustment in Bangkok also found attrition bias minimal.

- 27.

A later paper based on tracing over 10 vs. 4 years found more attrition effects, and recommended procedures to reduce attrition (Thomas et al. 2012).

- 28.

Cris Beauchemin (2013) presented a proposal to create a new Committee on Migration Data to the International Population Conference of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population in Busan, Republic of Korea, in August 2013.

References

Akee, R., & Kapur, D. (2012). Remittances and Rashomon (Working Paper 285). Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Aker, J. C., Boumnijel, R., & Tierney, N. (2011a). Zap it to me: The short-term impacts of a mobile cash transfer program (Working Paper 268). Washington, DC: Center for Global Development.

Aker, J. C., Clemens, M., & Ksoll, C. (2011b). Mobiles and mobility: The effect of mobile phones on migration in Niger. Boston: Tufts University.

Assaad, R. (2010). The impact of labor migration on those left behind: Evidence from Egypt. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, Middle East Institute.

Axinn, W. G., Barber, J., & Ghimire, D. (1997). The neighborhood history calendar: A data collection method designed for dynamic multilevel modeling. Sociological Methodology, 27, 355–392.

Axinn, W. G., Pearce, L., & Ghimire, D. (1999). Innovations in life history calendar applications. Social Science Research, 28, 243–264.

Ayhan, H. O., et al. (2000). Push and pull factors of international migration: Country report, Turkey (Population and Social Conditions 3/2000/E/no. 8). Luxembourg: European Commission.

Beauchemin, C. (2013, April 26). A proposal for an IUSSP panel on migration data (Presented to IUSSP in August). Paris: INED.

Bell, M., & Muhidin, S. (2009). Cross-national comparisons of internal migration (Human Development Research Paper no. 30). New York: UNDP Office of Human Development Report.

Bell, M., Blake, M., Boyle, P., Duke‐Williams, O., Rees, P., Stillwell, J., & Hugo, G. (2002). Cross‐national comparison of internal migration: Issues and measures. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 165(3), 435–464.

Bilsborrow, R. E. (2013). Sampling plans for MED-HIMS surveys. Paris: European Union; Eurostat/MEDSTAT; World Bank, UNFPA, UNHCR; League of Arab States.

Bilsborrow, R. E., & Lomaia, M., (2012). International migration and remittances in developing countries: Using household surveys to improve data collection in the CIS states and Eastern Europe. International Migration of Population in the Post-Soviet Territory in the Epoch of Globalization, 26, 10–40 (in English and Russian)

Bilsborrow, R. E., Oberai, A. S., & Standing, G. (1984). Migration surveys in low-income countries: Guidelines for survey and questionnaire design.. London/Dover: Croom Helm.

Bilsborrow, R., McDevitt, T., Kossoudji, S., & Fuller, R. (1987). The impact of origin community characteristics on rural–urban out-migration in a developing country (Ecuador). Demography, 24(2), 191–210.

Bilsborrow, R. E., Hugo, G., Oberai, A. S., & Zlotnik, H. (1997). International migration statistics: Guidelines for improving data collection systems. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Bilsborrow, R. E., Mena, C. F., & Arguello, E. (2011). Colombian refugees in Ecuador: Sampling schemes, migratory patterns, and consequences for migrants. International Journal of Global Environmental Issues, 11(3–4), 271–298.

Blangiardo, G. (1993). Una nuova metodologia di campionamento per le indagini sulla presenza straniera. In L. Di Comite & M. De Candia (Eds.), I fenomeni migratori nel bacino mediterraneo. Bari: Cacucci.

Blumenstock, J. E. (2012). Inferring patterns of internal migration from mobile phone call records: Evidence from Rwanda. Information Technology for Development, 18(2), 107–125.

Bogue, D., & Hauser, P. (1965). Population distribution, urbanism and internal migration. United Nations World Population Conference, Belgrade. Background Paper A.3/13/E/473.

Bohra, P., & Massey, D. (2009). Processes of internal and international migration from Chitwan, Nepal. International Migration Review, 43(3), 621–651.

Boyd, D. (2010, April 29). Privacy and publicity in the context of big data. Presented at WWW2010 conference, Raleigh, North Carolina.

Bustamente, J. A., Corona, R., & Santibáñez, J. (1994). Encuesta sobre Migración en la Frontera Norte de México: Síntesis Ejecutiva. Tijuana: El Colegio de la Frontera Norte, Consejo Nacional de Población, and Secretaria del Trabajo y Previsión Social.

Byerlee, D., & J. L. Tommy. (1976). An integrated methodology for migration research: The Sierra Leone migration survey. East Lansing: Michigan State University and Njala University College (Sierra Leone).

Castles, S., & Miller, M. (1998). The age of migration: International population movements in the modern world. Houndmills: Macmillan.

CEPAR. (2005). Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Materna e Infantil: ENDEMAIN IV. Quito/Ecuador/Atlanta: Centro de Estudios sobre Población y Desarrollo Social; Centers for Disease Control.

Chattopadhyay, A., White M. J., Debpuur, C. (2006). Migrant fertility in Ghana: Selection versus adaptation and disruption as causal mechanisms. Population Studies 60, 189–203. http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~content=a747863678~db=all

DaVanzo, J. (1981). Microeconomic Approaches to studying migration decisions, in DeJong and Gardner, op. cit., pp. 90–129.

Davis, K. (1974). The migrations of human populations. Scientific American, 231(3), 92–105.

de Brauw, A., & C. Carletto. (2009). Improving the measurement and policy relevance of migration information in multi-topic household surveys (Development Research Group) Washington, DC: The World Bank (unpublished).

DeJong, G. F., & Gardner, R. (Eds.). (1981). Migration decision-making: Multidisciplinary approaches to microlevel studies in developed and developing countries. New York: Pergamon Press.

Egypt. Central Agency for Public Mobilization and Statistics (CAPMAS). (2013). Household international migration survey (Egypt MED-HIMS). Cairo: CAPMAS, for Mediterranean Household International Migration Survey (MEd-HIMS).

European Union. (2007, July 11). Official statistics of the European union. Regulation No 862/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council.

Fei, J. C. H., & Ranis, G. (1976). A theory of economic development. American Economic Review, 5(4), 533–565.

Freedman, D., Thornton, A., Camburn, D., Alwin, D., & Young-DeMarco, L. (1988). The life history calendar: A technique for collecting retrospective data. Sociological Methodology, 18, 37–68.

Gile, K. J. (2011). Improved inference for respondent-driven sampling data with application to HIV prevalence estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 106(493), 135–146.

Goldstein, S., & Sly, D. (1975). The measurement of urbanization and projection of urban population. Liege: Ordina Editions, for the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population.

Gonzalez, M. C., Hidalgo, C., & Barabasi, A. (2008). Understanding individual human mobility patterns. Nature, 453(5), 779–782.

Goodman, L. A. (1961). Snowball sampling. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 32, 148–170.

Gray, C., & Bilsborrow, R E. (2013, January 15). Environmental influences on human migration in Ecuador. Demography (published on line, 2013).

Groenewold, G., & Bilsborrow, R. E. (2008). Design of samples for international migration surveys: Methodological considerations and lessons learned from a multi-country study in Africa and Europe. In B. Corrado, M. Okolski, J. J. Schoorl, & P. Simon (Eds.), International migration in Europe: current trends and issues. Rome: Universite di Roma.

Heckathorn, S. (1997). Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems, 44(2), 174–199.

Hilbert, M., & López, P. (2011). The world’s technological capacity to store, communicate, and compute information. Science, 332(6025), 60–65.

Hugo, G. (1981). Village-community ties, village norms, and ethnic and social networks: A review of evidence from the third world, in DeJong and Gardner, op. cit.

Kish, L. (1965). Survey sampling. New York: Wiley.

Lazar, D., & 14 co-authors. (2009). Computational social science. Science, 323, 721–723.

Lee, S.-h. (1985). Why people intend to move: Individual and community-level factors of outmigration in the Philippines. Boulder/London: Westview Press.

Lewis, W. A. (1954). Economic development with unlimited supplies of labor. The Manchester School of Economic and Social Studies, 22(2), 139–191.

Long, L. (1988). Migration and residential mobility in the United States (The population of the United States in the 1980s: A census bureau monograph). New York: Russell Sage.

Lucas, R. (2000). Migration. In M. Grosh & P. Llewwe (Eds.), Designing household survey questionnaires for developing countries: Lessons from 15 years of the living standards measurement study (Vol. 2, pp. 49–82). Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Massey, D., Williams, N., Axxin, W., & Ghimiri, D. (2009). Community services and out-migration. International Migration, 48(3), 1–41.

McKenzie, D., & Mistian, J. (2009). Surveying migrant households: A comparison of census-based, snowball, and intercept surveys. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 172(2), 339–360.

Moore, J. (1988). Self/proxy response status and survey response quality: A review of the literature. Journal of Official Statistics, 4(2), 155–172.

Moreno, L., White, M., & Guo, G. (1989). The use of a calendar to collect migration data: Places of residence. In N. Goldman, L. Moreno, & C. Westoff (Eds.), Peru experimental study: A comparison of child health information. Columbia: Institute for Resource Development.

Mushi, E., & Whittle, D. (2013, September 27). Voices of citizens: Africa’s first nationally representative mobile phone survey. Presented at seminar at Center for Global Development, Washington, DC. http://www.cgdev.org/event/africas-first-nationally-representative-mobile-phone-survey

Muto, M. (2009, August 16–22). The impacts of mobile phone coverage expansion and personal networks on migration: Evidence from Uganda. Contributed Paper presented at International Association of Agricultural Economics Conference, Beijing.

Ojeda, G., Ordoñez, M., & Ochoa, H. (2005). Salud Sexual y Reproductiva en Colombia: Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud 2005. Bogotá: Profamilia, and Columbia, MD., Macro International Inc.

Radloff, S. R. (1982). Measuring migration: A sensitivity analysis of traditional measurement approaches based on the Malaysian family life survey. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Sociology, Brown University, Providence, R.I.

Reed, H. E., Andrzejewski, C. S., & White, M. J. (2010). Men’s and women’s migration in coastal Ghana: An event history analysis. Demographic Research, 22, 771–812. http://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol22/25/22-25.pdf

Rindfuss, R. R., Kaneda, T., Chattopadhyay, A., & Sethaput, C. (2007). Panel studies and migration. Social Science Research, 36, 374–403.

Salganik, M. J., & Heckathorn, D. D. (2004). Sampling and estimation in hidden populations using respondent-driven sampling. Sociological Methodology, 34, 193–239.

Schoorl, A., Jeannette, J., Liesbeth, H., Ingrid, E., George, G., van der Erf, R. F., Alinda, B., de Valk, H., de Bruijn, B. J., European Commission, & Statistical Office of the European Communities. (2000). Push and pull factors of international migration: A comparative report. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Siegel, J., & Swanson, D. (Eds.). (2004). The methods and materials of demography (Secondth ed.). San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press.

Sirken, M. G. (1972). Stratified sample surveys with multiplicity. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 67(337), 224–227.

Sirken, M. G. (1998). A short history of network sampling. Proceedings of the American Statistical Association:, 1–6.

Sjaastad, L. (1962). The costs and returns of human migration. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5), 80–93.

Som, R. K. (1973). Recall Lapse in demographic enquiries. New York: Asia Publishing House.

Standing, G. (1984). Conceptualizing territorial mobility (Chap. 3). In R. E. Bilsborrow, A. S. Oberai, & G. Standing (Eds.), Migration surveys in low income countries: Guidelines for survey and questionnaire design (pp. 31–59). Croom Helm, Dover.

Stark, O. (1991). The migration of labor. Cambridge: Basil Blackwell.

Sudman, S., & Kalton, G. (1986). New developments in the sampling of special populations. Annual Review of Sociology, 1986(12), 401–429.

Sudman, S., Sirken, M., & Cowan, C. (1988, May 20). Sampling rare and elusive populations. Science, 240, 991–996.

Thomas, D., Frankenberg, E., & Smith, J. (2001). Lost but Not forgotten: Attrition and follow-up in the Indonesia family life survey. Journal of Human Resources, 36(3), 556–592.

Thomas, D., Witoelar, F., Frankenberg, E., Sikoki, B., Strauss, J., Sumantri, C., & Suriastini, W. (2012). Cutting the costs of attrition: Results from the Indonesia family life survey. Journal of Development Economics, 98(1), 108–123.

Todaro, M. (1969). A model of labor migration and urban unemployment in less developed countries. American Economic Review, 59(1), 138–148.

UN. (2005). World economic and social survey 2004: International migration and development. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, UN Publication Sales no. 04.II.C.3.

UN. (2006). International migration and development: Report of the Secretary-General. New York: UN General Assembly A/60/871.

UN GLobal Pulse. (2012). Big data for development: Opportunities and challenges (White Paper, by E. Letouzé). New York: United Nations. Retrieved from http://www.unglobalpulse.org/projects

United Nations. (1949). Problems of migration statistics (Population Studies No. 5). New York: Lake Success.

United Nations. (1972). Statistics of internal migration: A technical report. New York: UN Statistical Office.

United Nations. (1980). Recommendations on statistics of international migration (Statistical Papers No. 58). New York: UN Statistical Office.

United Nations. (1998). Recommendations on statistics of international migration, revision 1 (Statistical Papers Series M, No. 58, Rev. 1). New York: UN Statistical Office.

United Nations. (2008). Recommendations for statistics on population and housing censuses: Revision 2 (Series M, No. 67, Rev. 2). New York: UN Statistical Office.

United Nations. (2009a). Human development report 2009: Overcoming barriers; human mobility and development. New York: UN Development Program.

United Nations. (2009b). International migration 2009 (wall chart). New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

United Nations. (2012). World urbanization prospects: The 2011 revision. New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

United Nations. (2013). International migration 2013 (wall chart). New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

United Nations. (Forthcoming). Technical report on the use of censuses and surveys to measure international migration. New York: United Nations Statistical Office.

van den Brekel, J. (1977). The population register: The example of the Netherlands system (Laboratories for population statistics scientific report series no. 11). Chapel Hill: Department of Biostatistics, University of North Carolina.

Van Dalen, H., & Kene, H. (2008). Emigration intentions: Mere words or true plans? Explaining international migration intentions and behavior. The Hague: NIDI.

Verdery, A., Mouw, T., Bauldry, S., & Mucha, P. (2013). Network structure and biased variance estimation in respondent driven sampling. Chapel Hill: Carolina Population Center.

Westoff, C., & Ryder, N. (1977). The predictive validity of reproductive intentions. Demography, 14(4), 431–453.

White, M. J., & Lindstrom, D. P. (2005). Chapter 11: Internal migration. In D. L. Poston & M. Micklin (Eds.), Handbook of population. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

White, M. J., & Mueser, P. R. (1988). Implications of boundary choice for the measurement of residential mobility. Demography, 25, 443–459. doi:10.2307/2061543.

Wikepedia. (2013a). Big data. Accessed Nov 13.

Wikepedia. (2013b). List of countries by mobile phones in use. Accessed Nov 14.

Williams, N. (2009). Education, gender, and migration in the context of social change. Social Science Research, 38(4), 883–896.

World Bank and Quentin Wodon. (2003). International migration in Latin America: Brain drain, remittances and development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Yamanis, T. J., Merli, M. G., Neely, W., Feng Tian, F., Moody, J., Tu, X., & Gao, E. (2013). An empirical analysis of the impact of recruitment patterns on RDS estimates among a socially ordered population of female sex workers in China. Sociological Methods & Research, 42(3), 392–425.

Yang, X. (1994). A sensitivity analysis of repeat migration attrition in the study of migrant adjustment: The case of Bangkok. Demography, 31(4), 585–592.

Yang, X., & Bilsborrow, R. E. (1993). Survey locale and biases in the data collected. Unpublished, Chapel Hill: Carolina Population Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix A. Example of “Last Move” Questionnaire (Adapted from Survey on International Migration in Tajikistan , 2013; English draft of R. Bilsborrow, for the World Bank )

Section 7. Migrant Questionnaire

Instructions for interviewer: This section is only for persons who left within the past 10 years and were at least 15 years old at the time of leaving. This refers to their last outmigration from the household (hh), in case the person X had left before, whether during the reference period or previously. The (proxy) respondent providing information about the out-migrant should be the person in the household most knowledgeable about the migrant.

-

7.1

What is the name (X) of the out-migrant?

-

7.2

Gender: 1 Male 2 Female

-

7.3

When did X leave this hh to live elsewhere (another district, province, or country) (last time, if X had also left to live elsewhere earlier but returned)?

-

7.4

How old was X at that time?

-

7.5

Why did X leave here? (ALLOW MULTIPLE RESPONSES)

-

1.

To work

-

2.

To study

-

3.

To marry, accompany spouse or boy/girlfriend

-

4.

To accompany other family member

-

5.

Family, personal problems with some family member

-

6.

Personal problems with someone else

-

7.

Political problems/conflicts with government

-

8.

Other [specify___________________)

-

9.

Don’t know (DK)

-

1.

-

7.6

Who made the decision for X to migrate?

-

7.7

At the time when X left, who was living in your household ?

-

1.

Same as current hh composition (see Household Roster in section 1; confirm it is identical)

-

2.

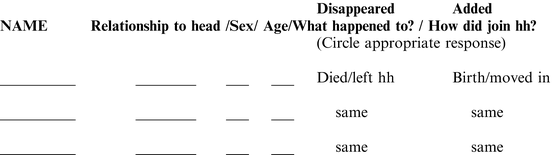

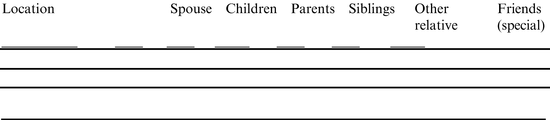

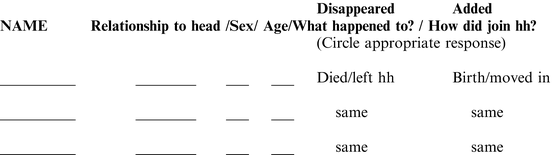

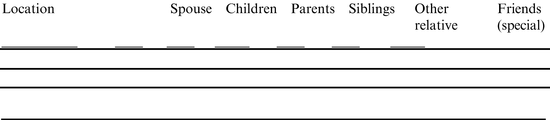

Different from current composition: Please tell me about any persons who were in the hh then but no longer are, and which members in the hh now were not in the hh at the time MMYYYY when X left (COMPLETE LIST BELOW)

-

1.

-

7.8

Why did X go to that particular destination ? (CIRCLE RESPONSES MENTIONED.)

-

1.

Thought there were jobs there, or work with better pay

-

2.

Had job waiting, or transferred by employer

-

3.

Had close relatives/friends there

-

4.

Had good information about it

-

5.

Close, not expensive to travel there

-

6.

Knew there were people there from this community

-

7.

More, better quality of land there

-

8.

Good prospects to open business there

-

9.

Better education there, for self or children

-

10.

Better quality of life there

-

11.

Better climate

-

12.

Better health care

-

13.

Other (specify ______________)

-

1.

-

7.9

Did X have any relatives or close friends living in (DESTINATION) or in any other location outside this district before X moved there?

-

1.

Yes

-

2.

No (SKIP TO 7.11)

-

1.

-

7.10

In which places principally (tell me how many of each of the following were already living abroad (in ANY foreign country) when X left to live in (CURRENT RESIDENCE)?

-

7.11

What was the marital status of X at the time of leaving? ______

-

7.12

Did he/she move with anyone else then (or within 3 months, did others join him/her)?

-

1.

Yes

-

2.

No (SKIP TO 7.14)

-

1.

-

7.13

Who accompanied X (or joined X within a few months after)?

-

7.14

What was the level of educational attainment of X when he/she left?

-

7.15

During the period of 3 months prior to leaving, was he/she mainly ……

-

1.

Working?

-

2.

Looking for work? 7.16 How long? _________Mos.

-

3.

Studying? (SKIP TO 7.33)

-

4.

Taking care of own children, doing housework at home, etc.? (SAME)

-

5.

Other? (specify______) (SAME)

-

9.

DK

-

1.

-

7.17

Was (X) working for pay for someone or for a business, or making income from his/her own business of any kind, or managing a farm, in the last months before leaving?

-

1.

Yes, working for pay

-

2.

Yes, managing some kind of business or service (SKIP TO 7.22)

-

3.

Yes, farming (SKIP TO 7.27)

-

4.

No, just looking for work (SKIP TO ZZ)

-

1.

-

7.18

What was his/her occupation? __________________________________

-

7.19

What was the main economic activity of the place where X worked? _______________

-

7.20

Was X working full time or part time?

-

7.21

About how much do you think he/she was earning then? _______

(SKIP TO 7.33)

-

7.22

What kind of business or service did X have here in the last months before moving?

-

1.

Manufacture something _____________________________

-

2.

Repair something ________________________________

-

3.

Professional, such as lawyer, doctor, accountant, etc., with own office ___________

-

4.

Rent out land or building

-

5.

Buy and/or sell things

-

6.

Have restaurant, or cook and sell food to others

-

7.

Personal services, such as washing clothes, providing haircuts, massage, etc..

-

8.

Other (specify _________________ )

-

1.

-

7.23

Did he/she have a building or fixed location to operate this business (not part of home dwelling)?

-

1.

Yes

-

2.

No

-

1.

-

7.24

Did X have any paid employees?

-

1.

Yes

-

2.

No (SKIP TO 7.26)

-

1.

-

7.25

About how many (most of the time, on average)?

-

1.

1–3

-

2.

4–9

-

3.

10–99

-

d.

4.100+

-

1.

-

7.26

Taking into account his/her costs of materials, and any other costs for labor, utilities, rent, etc., about how much net income or profits do you think X was making in a normal month in the months before leaving?

-

1.

__________

-

2.

Refused

-

3.

DK

(SKIP TO 7.33)

-

1.

-

7.27

On the farm that X managed in the months before leaving, how much land did X have?

-

1.

Owned ______ ha

-

2.

Rented ______ ha

-

3.

Provided rent free _______ ha

-

4.

Other (specify _____________ )

-

5.

TOTAL LAND available __________ ha

-

1.

-

7.28

Did X grow crops? Major crops 1. ________ 2. __________ 3. _________

-

7.29

Did X raise animals? Type of animal 1. _______ 2. ________ 3 ________

-

7.30

Did he/she have any farm employees?

-

1.

Temporary workers, at planting, harvesting, etc., times

Number total during year estimated _________ (person-months)

-

2.

Permanent workers all year

Number _____________ 3 None

-

1.

-

7.31

Did X have any of the following to use on the farm

-

1.

Farm building(s)

-

2.

Tractor

-

3.

Other farm machinery

-

3.

Farm tools

-

1.

-

7.32

About how much net income do you think X made during the 12 months before leaving (or how much per month on average, counting good months of harvests or animal sales and other months of little or no sales)? __________

-

7.33

Has X worked since arriving at (DESTINATION)?

-

7.34

When did his/her most recent/current work begin? MMYYYY

Etcetera on living conditions, etc., in place of destination (for studies on consequences).

Now I would like to ask you about whether you have ever sent any money to help X, or if he/she has ever sent anything to you or anyone in your household .

-

8.1

When X left your household to live elsewhere, did you/your household give him/her any money to help him/her, to pay for the trip or to help him/her when he/she first arrived in DESTINATION? (last time, if left more than once)

-

1.

Yes

-

2.

No (SKIP TO 8.3)

-

1.

-

8.2

About how much did you give X then? ________

-

8.3

Did you later send X any money?

-

1.

Yes, in the first months after he/she arrived there

-

2.

Yes after that

-

3.

No (SKIP TO 8.5)

-

1.

-

8.4

Have you sent X any money or goods in the past 12 months?

-

1.

Yes, money 8.4a How much altogether? _________

-

2.

Yes, goods 8.4b About how much were these goods worth? ______

-

3.

No

-

1.

-

8.5

And since X arrived in DESTINATION, has he/she ever sent you any money or goods?

-

1.

Yes

-

2.

No (END OF INTERVIEW)

-

8.5a

When was the first time X sent you anything? MMYYYY

-

8.5b

Has he/she also sent you something since then, whether regularly or not?

-

1.

Yes, monthly or more often

-

2.

Yes, quarterly

-

3.

Yes, irregular

-

4.

Yes, about once per year

-

5.

Yes, less often than once per year

-

6.

No

-

1.

-

1.

-

8.6

Has he/she sent you or anyone in your household any money or goods in the past 12 months?

-

1.

Yes

-

2.

No (END OF INTERVIEW)

-

8.6a

When was the last time X sent money? MMYYYY

-

8.6b

How much did he/she send? ___________

-

8.6c

Is this about what he/she usually sends?

-

1.

Yes

-

2.

No 8.6d How much does he/she usually send? __________

-

1.

-

8.6d

How many times did X send money to this household in the past 12 months? ___

-

8.6e

About how much altogether did X send in the past 12 months? ________

-

8.6f

How does he/she usually send the money?

-

1.

Western Union

-

2.

MoneyGram

-

3.

Bank transfer

-

4.

Money Order through post office, cashier check

-

5.

Through a courier, friend

-

6.

Using mobile telephone

-

7.

Other (specify _______)

-

1.

-

8.6g

Did X also send any goods to the household in the past 12 months, like appliances, furniture, etc.?

-

1.

Yes Which items? _________

-

2.

No

-

1.

-

8.6h

Did he/she (also) bring any money or goods in person in any visits to your house during the past 12 months? (if made more than one visit with goods, combine). Do not include normal gifts for birthdays.

-

1.

Yes, money ——8.6i Total amount ______________

-

2.

Yes, goods —— GO TO 8.6j

-

3.

No (END OF INTERVIEW)

-

1.

-

8.6j

What kind of goods did X send (8.6g) or bring to the household in the past 12 months?

-

8.6k

About how much do you think all these things are worth? ____________

-

1.

-

8.7

(Check response to 8.h, if answers code 1 continue, if not, END INTERVIEW)

Thinking of the money X has sent you or brought you in the past 12 months, how was it used? (READ EACH ITEM.)

END OF INTERVIEW ABOUT OUT-MIGRANT FROM HOUSEHOLD

APPENDIX B. Adapted from “Survey on Migration and Natural Resources, Ecuador , 2008” (developed by Clark Gray and Richard Bilsborrow)

C. INDIVIDUAL HISTORY

(Complete one sheet for each resident aged 14+ in the year and for each former member who was 14+ at the time of migrating away or dying.)

I am going to ask you about some events in the life of this person beginning with the year 2000.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bilsborrow, R.E. (2016). Concepts, Definitions and Data Collection Approaches. In: White, M. (eds) International Handbook of Migration and Population Distribution. International Handbooks of Population, vol 6. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-7282-2_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-7282-2_7

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-017-7281-5

Online ISBN: 978-94-017-7282-2

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)