Abstract

Unlike run-of-the-mill quantifiers, indefinites can escape islands. Schwarzschild (J Semant 19(3):289–314, 2002) connects this behavior with domain restriction: On his analysis, indefinites are existential quantifiers that get apparent exceptional scope when their domain is restricted to a singleton. The Spanish indefinites un and algún provide an ideal testing ground for Schwarzschild’s theory. Since un can be a singleton indefinite but algún cannot (Alonso-Ovalle and Menéndez-Benito, Nat Lang Semant 18(1): 1–31, 2010, (2008b) Minimal domain widening. In: Abner N, Bishop J (eds) Proceedings of the 27th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics. Cascadilla Proceedings Project, Somerville, MA, pp 36–44), we only expect un to have exceptional scope. This chapter tests this prediction experimentally by looking at the behavior of these indefinites in relative clauses and the antecedent of conditionals. The results yield a modulation of the predicted pattern: (1) In relative clauses, un can have exceptional scope, but exceptional scope is also available for algún to some extent; (2) in conditionals, exceptional scope is impossible for algún and hard for un. This difference between the two types of islands is puzzling for most theories of indefinites. We put forward an account cast within Kratzer and Shimoyama’s ((2002) Indeterminate pronouns: the view from Japanese. In: Otsu Y (ed) Proceedings of the 3rd Tokyo conference on psycholinguistics, pp 1–25) Hamblin semantics, on which indefinites denote sets of alternatives that expand until they meet an appropriate operator. Under this account, the differences between the two islands come about through the interplay of the alternatives introduced by the indefinite and the operators associated with each syntactic configuration.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

See, for instance, Matthewson (1999) on Lilloet Salish; Farkas (2000) on Romanian; Yanovich (2005) and Ionin (this volume) on Russian; Lin (2004) and Kim (2004) on Mandarin Chinese; Martí (2007) on Spanish; Ebert et al. (this volume) on German ein gewiss vs. ein bestimmt; Martin (this volume), Jayez and Tovena (2002), and Jayez and Tovena (2006) on French; and Yanovich (this volume) on a certain.

- 3.

- 4.

See Frazier and Bader (2007) for an overview of previous psycholinguistic studies on quantifier scope.

- 5.

In this connection, see Zamparelli (2007), who claims that Italian qualche, a domain widener, cannot escape out of islands.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

Schwarzschild’s theory also covers cases of exceptional scope where the indefinite scopes out of a scope island but underneath a higher quantifier (“intermediate readings”). In what follows, we will leave those readings aside. We will briefly come back to them in Sect. 6.3.

- 9.

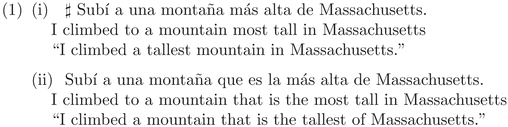

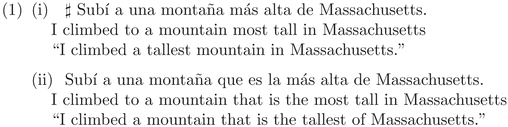

Note that the relative clauses in these examples are restrictive (Schwarz et al., forthcoming). First, there is no intonational break, unlike the case of nonrestrictive clauses. Second, unlike nonrestrictive relative clauses, the relative clauses in these examples do not have to be speaker oriented (Potts, 2003), as shown by the example below.

Note also that while in these examples the domain of un is a singleton, un cannot combine with nouns whose extension is known to be a singleton, as illustrated below (Heim, 1991; Percus, 2006). The contrast between the sentences below is explored in Schwarz et al. (forthcoming).

- 10.

The definition of an antisingleton subset selection function is based upon the definition of a singleton subset selection function presented in von Fintel (1999). Of course, other domain constraints may be possible. For instance, certain indefinites have been argued to widen the domain (Kadmon and Landman, 1993; Kratzer, 2003; Chierchia, 2006). Domain widening would correspond to the requirement that f be interpreted as an identity function. For the sake of concreteness, we are assuming that the antisingleton constraint is a presupposition on the value of the subset selection function. The function in (10a) is partial. Following the notation in Heim and Kratzer (1998), the expression right before the colon indicates the definedness condition.

- 11.

The complete list of experimental items is available upon request.

- 12.

The partitive versions were included to determine whether partitivity had an effect on the availability of exceptional scope—Frazier and Bader (2007) found that partitive complements may facilitate specific interpretations. However, partitivity was not found to be relevant and will be ignored in the remainder of this chapter.

- 13.

This was done to give the wide-scope reading all the chances possible, since bound variable pronouns have been argued to facilitate exceptional scope (see Kratzer (1998)).

- 14.

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) test looking at both experiments together revealed a significant main effect of un vs. algún (F1(1,23) = 59.213, p < 0.001, F2(1,22) = 102.859, p < 0.001 ), a significant main effect of syntactic environments (conditionals vs. relative clauses) (F1(1,23) = 49.286, p < 0.001, F2(1,22) = 101.669, p < 0.001), and a significant interaction (F1(1,23) = 6.273, p < 0.05, F2(1,22) = 11.017, p < 0.01 ). Of course, the by-items analysis is of limited use here, since the items where not minimal variants of one another.

- 15.

Martí (2007) argues that the scope of algunos, the plural version of algún, is constrained by a wide range of syntactic islands. Interestingly, the data she presents suggests that wide-scope readings might be harder for algunos in conditionals. This could reflect the same type of pattern that we find for algún. Similarly, Ionin (2010b) presents the results of an experiment that tests the availability of narrow, intermediate, and widest possible scope for a certain and a indefinites in relative clauses and conditionals, and reports that there are numerically more acceptances of widest-scope readings of a-indefinites out of relative clauses than out of conditionals (although the difference was not replicated in the case of intermediate scope readings).

- 16.

- 17.

For concreteness, we will assume that the subset selection function is syntactically represented, the way the C variable used to account for quantifier restrictions is often assumed to be (see, for instance, von Fintel, 1994).

- 18.

- 19.

We are making what Lewis calls “The Limit Assumption” (Lewis, 1973), namely, that given a proposition p, there will always be a non-empty set of worlds in which p is true that come as close as possible to the world of evaluation. Ties in similarity are allowed. For a survey of the different flavors a minimal change semantics might come in, see Nute (1984).

- 20.

The problem also arises with might counterfactuals and, in general, with other conditionals for which an ordering semantics is assumed (a downward monotone analysis licenses the inference from (p ∨ q) → r to p → r and q → r), but see Alonso-Ovalle (2006) for reasons to believe that the inference we are after is not a downward entailing inference.

- 21.

Assume that the CP and the IP combine once the free variable in the IP is abstracted over.

- 22.

For ease of exposition, we assume that the lambda abstraction is represented at LF by means of an index, as in Heim and Kratzer (1998).

- 23.

This means, under our assumptions, that the value of the subset selection function variable introduced by algún is the identity function.

- 24.

An anonymous reviewer points out that the English counterpart of (38b) with any can be naturally read as quantifying over those articles of Juan that he published in a foreign journal.

- 25.

Thanks to Maribel Romero (p.c.) for bringing this point to our attention.

- 26.

Of course, a process of free existential closure has been proposed before. See, for instance, Reinhart (1997).

- 27.

Maribel Romero (p.c.) suggests that different islands might treat the alternatives introduced by disjunction differently: As we saw in connection with example (43), a complex-NP island simply lets alternatives pass. In contrast, wh-islands seem to stop them, as in (i), from Larson (1985, 245). Larson judges the reading in (ii) as “at best quite marginal”:

- 28.

Alonso-Ovalle and Menéndez-Benito (2010) analyze this ignorance component as a conversational implicature derived by the antisingleton constraint imposed by algún.

- 29.

Thanks to Maribel Romero (p.c.) for making this suggestion and sharing her intuition about the context below.

- 30.

As in experiment 1, each sentence was preceded by a paragraph describing a situation forcing the intermediate scope reading of the sentence (the reading under which the indefinite is interpreted scoping under the subject quantifier but over the universal quantifier in object position). As above, each context was followed by a question asking subjects whether the target sentence was an appropriate description of the scenario.

References

Abusch, D. 1994. The scope of indefinites. Natural Language Semantics, 2: 83–135.

Aloni, M. 2003. Free choice in modal contexts. In Proceedings of the conference “SuB7 – Sinn und Bedeutung”. Arbeitspapier Nr. 114, ed. M. Weisgerber, 28–37. Konstanz: Universität Konstanzs.

Alonso-Ovalle, L. 2006. Disjunction in alternative semantics. Ph.D thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Alonso-Ovalle, L. 2009. Counterfactuals, correlatives and disjunction. Linguistics and Philosophy 32(2): 207–244.

Alonso-Ovalle, L., and P. Menéndez-Benito. 2008a. Another look at indefinites in islands. Ms. University of Massachusetts, Amherst/Boston.

Alonso-Ovalle, L., and P. Menéndez-Benito. 2008b. Minimal domain widening. In Proceedings of the 27th west coast conference on formal linguistics, ed. N. Abner and J. Bishop, 36–44. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Alonso-Ovalle, L., and P. Menéndez-Benito. 2010. Modal indefinites. Natural Language Semantics 18(1): 1–31.

Beghelli, F. 1993. A minimalist approach to quantifier scope. In Proceedings of NELS 23, 65–80. Amherst: GLSA.

Bhatt, R., and R. Pancheva. 2006. Conditionals. In The Blackwell Companion to Syntax, vol. I, 638–687. Malden: Blackwell.

Chierchia, G. 2006. Broaden your views. Implicatures of domain widening and the ‘logicality’ of language. Linguistic Inquiry 37(4): 535–590.

Cresti, D. 1995. Indefinite topics. Ph.D thesis, MIT, Cambridge.

Darlrymple, M., M. Kanazawa, M. Kim, S. Mchombo, and S. Peters. 1998. Reciprocal expressions and the concept of reciprocity. Linguistics and Philosophy 21: 159–210.

Dayal, V. 1995. Quantification in correlatives. In Quantification in natural languages, ed. E. B. et al., 179–205. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Dayal, V. 1996. Locality in W-Quantification. Questions and Relative Clauses in Hindi. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Ebert, C., C. Ebert, and S. Hinterwimmer. this volume. The interpretation of the German specificity markers Bestimmt and Gewiss. In Different kinds of specificity across languages. Studies in Linguistics and Philosophy 92, eds. C. Ebert, and S. Hinterwimmer, 31–74. Dordrecht: Springer.

Farkas, D. 1981. Quantifier scope and syntactic islands. In Chicago Linguistics Society, vol. 17, ed. by Roberta A. Hendrick, Carrie S. Masek and Mary Frances Miller, 59–66. Chicago: CLS.

Farkas, D. 2000. Extreme non-specificity in Romanian. In Romance languages and linguistic theory, ed. C. B. et al., 127–151. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Farkas, D.F. 2002. Varieties of indefinites. In Proceedings of SALT XII, ed. B. Jackson, 59–83. Ithaca: Cornell University/CLC.

Fodor, J., and I. Sag. 1982. Referential and quantificational indefinites. Linguistics and Philosophy 5: 355–398.

Frazier, L., and M. Bader. 2007. Reconstruction, scope, and the interpretation of indefinites. Ms. University of Massachusetts Amherst and University of Konstanz.

Hamblin, C. 1973. Questions in Montague English. Foundations of Language 10: 41–53.

Heim, I. 1991. Artikel und definitheit. In Semantik: Ein internationales Handbuch der zeigenossischen Forschung, ed. A. von Stechow and D. Wunderlich, 487–535. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Heim, I., and A. Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in generative grammar. Malden: Blackwell.

Hintikka, J. 1986. The semantics of A Certain. Linguistic Inquiry 17: 331–336.

Ionin, T. this volume. Pragmatic variation among specificity markers. In Different kinds of specificity across languages. Studies in Linguistics and Philosophy 92, eds. C. Ebert, and S. Hinterwimmer, 75–704. Dordrecht: Springer.

Ionin, T. 2008. An experimental investigation of the semantics and pragmatics of specificity. In Proceedings of the 27th West coast conference on formal linguistics, ed. N. Abner and J. Bishop, 229–237. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Ionin, T. 2010a. An experimental study on the scope of (un)modified indefinites. International Review of Pragmatics 2: 228–265.

Ionin, T. 2010b. The scope of indefinites: An experimental investigation. Natural Language Semantics 18: 295–350.

Izvorski, R. 1996. The syntax and semantics of correlative proforms. In Proceedings of NELS 26, ed. K. Kusumoto, 189–203. Amherst: GLSA.

Jayez, J., and L. Tovena. 2002. Determiners and (un)certainty. In Proceedings of SALT XII, edited by Brendan Jackson. 164–183.

Jayez, J., and L. Tovena. 2006. Epistemic determiners. Journal of Semantics 23: 217–250.

Kadmon, N., and F. Landman. 1993. Any. Linguistics and Philosophy 16(4): 353–422.

Kim, J.-Y. 2004. Scope: The view from Indefinites. Ph.D thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

King, J.C. 1988. Are indefinite descriptions ambiguous? Philosophical Studies 53(3): 417–440.

Kratzer, A. 1998. Scope or pseudoscope? Are there wide scope indefinites? In Events and grammar, ed. S. Rothstein, 163–196. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Kratzer, A. 2003. Indefinites and functional heads: From Japanese to Salish. Talk given at SALT 13, University of Washington, Seattle.

Kratzer, A. 2005. Indefinites and the operators they depend on: From Japanese to Salish. In Reference and quantification: The Partee effect, ed. G.N. Carlson and F. Pelletier, 113–142. Stanford: CSLI.

Kratzer, A., and J. Shimoyama. 2002. Indeterminate pronouns: The view from Japanese. In Proceedings of the 3rd Tokyo conference on psycholinguistics, ed. Y. Otsu, Hituzi Syobo: Tokyo. 1–25.

Larson, R.K. 1985. On the syntax of disjunction scope. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 3(2): 217–264.

Lewis, D. 1973. Counterfactuals. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lewis, D. 1977. Possible-world semantics for counterfactual logics: A rejoinder. Journal of Philosophical Logic 6: 359–363.

Lin, J.-W. 2004. Choice functions and scope of existential polarity wh-phrases in Mandarin Chinese. Linguistics and Philosophy 27(4): 451–491.

Liu, F.-H. 1997. Scope and specificity. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Martí, L. 2007. Restoring indefinites to normalcy: An experimental study on the scope of Spanish algunos. Journal of Semantics 24(1): 1–25.

Martin, F. this volume. Specificity markers and nominal exclamatives in french. In Different kinds of specificity across languages. Studies in Linguistics and Philosophy 92, eds. C. Ebert and S. Hinterwimmer, 11–30. Dordrecht: Springer.

Matthewson, L. 1999. On the interpretation of wide-scope indefinites. Natural Language Semantics 7(1): 79–134.

Nute, D. 1975. Counterfactuals and the similarity of worlds. Journal of Philosophy 72: 773–778.

Nute, D. 1984. Conditional logic. In Handbook of philosophical logic, vol. II, ed. D. Gabbay and F. Guenthner, 387–439. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Percus, O. 2006. Antipresuppositions. In Theoretical and empirical studies of reference and anaphora: Toward the establishment of generative grammar as an empirical science, 52–73. Report of the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), Project No. 15320052, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Potts, C. 2003. The logic of conventional implicatures. Ph.D thesis, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Reinhart, T. 1995. Interface strategies. OTS, University of Utrecht. http://igitur-archive.library.uu.nl/let/2006-1215-203412/UUindex.html

Reinhart, T. 1997. Quantifier scope: How labor is divided between QR and choice functions. Linguistics and Philosophy 21(1): 95–115.

Rooth, M., and B. Partee. 1982. Conjunction, type ambiguity, and wide scope or. In Proceedings of the first West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, ed. D. Flickinger, M. Macken and N. Wiegand, 353–362. Stanford: Stanford Linguistics Association.

Ruys, E. 1992. The scope of indefinites. Ph.D thesis, Utrecht.

Schlenker, P. 2004. Conditionals as definite descriptions (a referential analysis). Research on Language and Computation 2(3): 417–462.

Schwarz, F., L. Alonso-Ovalle, and P. Menéndez-Benito. forthcoming. Maximize Presupposition and two types of definite competitors. In Proceedings of NELS 39. Amherst: GLSA.

Schwarzschild, R. 2002. Singleton indefinites. Journal of Semantics 19(3): 289–314.

Shimoyama, J. 2001. Wh-constructions in Japanese. Ph.D thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Simons, M. 2005. Dividing things up: The semantics of or and the modalor interaction. Natural Language Semantics 13: 271–316.

Srivastav, V. 1991a. The syntax and semantics of correlatives. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 9: 637–686.

Srivastav, V. 1991b. Wh-dependencies in Hindi and the theory of grammar. Ph.D thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca.

Szabolcsi, A. 1996. On modes of operation. In Proceedings of the 10th Amsterdam Colloquium, ed. P. Dekker and M. Stokhof 651–669.

von Fintel, K. 1994. Restrictions on quantifier domains. Ph.D thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

von Fintel, K. 1999. Quantifier domain selection and pseudo-scope. Paper presented at the Cornell conference on context-dependence.

von Fintel, K. 2000. Singleton indefinites (re. schwarzschild 2000). Ms., MIT.

Winter, Y. 1997. Choice functions and the scopal semantics of indefinites. Linguistics and Philosophy 20(4): 399–467.

Yanovich, I. this volume. Certain presuppositions and some intermediate readings, and vice versa. In Different kinds of specificity across languages. Studies in Linguistics and Philosophy 92, eds. C. Ebert and S. Hinterwimmer, 105–122. Dordrecht: Springer.

Yanovich, I. 2005. Choice-functional series of indefinite pronouns and Hamblin Semantics. In Proceedings of SALT XV, ed. E. Georgala and J. Howell. Ithaca: CLC, 309–326.

Zamparelli, R. 2007. On singular existential quantifiers in Italian. In Existence: Semantics and syntax, ed. I. Comorovski and K. von Heusinger, 293–328. Berlin: Springer.

Acknowledgements

For their invaluable help with this project, we would like to thank Leopoldo Abad Alcalá, Jan Anderssen, Ana Arregui, Sandra Barriales, Patrick Brand, Rajesh Bhatt, Manuel Carreiras, Francisco Conde, Kai von Fintel, Lyn Frazier, Danny Fox, Valentine Hacquard, Susana Huidobro, Jonah Katz, Angelika Kratzer, Helen Majewski, Norberto Moreno, Manolo Perea, Maribel Romero, Florian Schwarz, Anne-Michelle Tessier, and audiences at the workshop on ‘Funny Indefinites’ held in ZAS, Berlin, on July 6–7 2007, and at WCCFL 2008. We are also very grateful to an anonymous reviewer for insightful comments and helpful suggestions and to Stefan Hinterwimmer and Cornelia Ebert for their careful editorial work. Of course, all errors are our own. Our names are listed in alphabetical order.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Alonso-Ovalle, L., Menéndez-Benito, P. (2013). Exceptional Scope: The Case of Spanish. In: Ebert, C., Hinterwimmer, S. (eds) Different Kinds of Specificity Across Languages. Studies in Linguistics and Philosophy, vol 92. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5310-5_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5310-5_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-5309-9

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-5310-5

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)