Abstract

This chapter proposes analyses for a variety of constructions that resemble noun incorporation in a number of languages using the theory of phrase structure developed in Chapter 3. First, it discusses the general structure of the extended nominal projection. This section also relates linear order in NI constructions to the structure of nominals. This chapters specifically examines NI in Sierra Popoluca, English gerunds, noun+verb compounding in German progressive-beim constructions, a kind noun+of NI in Persian ‘long’ infinitives, a construction in Tamil which has been argued to be noun incorporation, and finally adverb incorporation in Blackfoot. In all cases, incorporation is handled by the dynamic antisymmetric theory proposed in Chapter 3.

Keywords

In this chapter, I propose analyses for a variety of constructions that resemble noun incorporation in a number of languages using the theory of phrase structure developed in Chapter 3. This chapter is organized as follows. In Section 5.1, I discuss the general structure of the extended nominal projection, although I do not make any strong claims on a universal nominal hierarchy. This section also relates linear order in NI constructions to the structure of nominals. In Section 5.2, I discuss NI in Sierra Popoluca . In Section 5.3, I discuss the patterns of noun incorporation found in English gerunds and give an analysis of these structures using a Dynamic Antisymmetric formulation of Bare Phrase Structure. In Section 5.4, I look at related phenomena in German . Specifically, I examine noun+verb compounding in German progressive-beim constructions. Section 5.5 examines a kind of NI in Persian ‘long’ infinitives. Next, in Section 5.6, I look at a construction in Tamil which has been argued to be noun incorporation. Section 5.7 looks at adverb incorporation in Blackfoot and shows that it arises as a symmetry breaking operation, too. Section 5.8 is a brief conclusion.

5.1 The Structure of Nominals and V/IN Order

Note that some of the material presented in this section is based on joint work with Martina Wiltschko.

This first section discusses the structure of the extended nominal projection and how it related to the order between the verb and the IN. The structure of the extended nominal domain has been the subject of interest to a great many researchers since Abney’s (1987) influential DP hypothesis (Ritter 1992, 1993; Valois 1991; Megerdoomian 2008; Travis 1992; Wiltschko 2008; Ghomeshi 2003). The following structure shows a typical extended nominal projection based on the references just mentioned.Footnote 1

1. | |

|

A couple points bear mentioning here. First, I do not pretend to present a universal functional hierarchy for the nominal domain or even argue that one exists (indeed, some of the references above discuss variation in the nominal hierarchy). Such a task is beyond the purview of this monograph. As such, in the discussions of individual languages below, the reader will see that the structure of nominals varies from language to language. Second, the reader will notice that there are two nP projections in the structure above. I adopt Newell’s (2008) distinction between vP and vP and extend this to the nominal domain (though I do not adopt the orthographic convention here). For Newell, v is a verbalizing head (such as -ate or -ize in English) whereas v is the head that introduces the external argument and assigns accusative Case.Footnote 2 The lower n head (Newell’s n) is a nominalizing head (such as -ion or -er in English). The higher n head is argued to play a similar role as v. It defines a phase and introduces a possessor. Crucially, as a phase head, the higher n determines a domain for stress assignment (Marvin 2003).

I adopt Ghomeshi’s (2003) proposal that the count/mass distinction is encoded on Num as follows.Footnote 3

2. Number Heads | |

| |

Additional evidence for this claim comes from the following English paradigm (discussed in detail below).

3. | a. | Maxwell enjoys washing glasses |

b. | Maxwell enjoys washing glass. | |

c. | Maxwell enjoys glass-washing. |

In 3a and b, the noun glass obligatorily receives a count and mass interpretation, respectively. In 3c, however, the form glass is vague between these two readings. Spanish dialects with overt morphology and agreement for mass (Penny 1970; Hualde 1992) also support a representation as in 2. Consider the following Asturian Spanish data.

4. | a. | nígr-u [‘black’ - sg.masc] |

b. | négr-a [‘black’ - sg.fem] | |

c. | négr-o [‘black’ - mass ] |

5. | a. | el | kafé | négr-o | ||

the.masc | coffee.masc | black- mass | ||||

‘the black coffee’ | ||||||

b. | la | boróna | négr-o | |||

the.fem | cornbread.fem | black- mass | ||||

‘the black cornbread’ | ||||||

c. | la | maéra | tába | sék-a | ||

the.fem | piece.of.wood.fem | was | dry-fem | |||

‘the piece of wood was dry’ | ||||||

What we observe here is that adjectives agree not only with number (plural and singular) but also with mass . Thus, mass, rather than being the absence of number, in fact interacts with number.

Given the variable size of the IN and the theory of phrase structure proposed in Chapter 2, I predict that smaller INs are more likely to appear with N+V order while larger INs are more likely to appear with V+N order. To understand why this is so, let us consider the following hypothetical structures, where V is used to represent the verbal root for clarity.

6. | |

|

Recall that in order to get N+V order, Complement-to-Spec roll-up must take place up until the verbal root is introduced into the derivation. In order for this to happen, every head merged into the derivation must have some phonological content (or at least have an allomorph with phonological content). Thus, in the case where a bare verbal root merges with an IN that is itself a bare nominal root, N+V order is expected universally (the first small tree shown above). If the IN contains just one functional projection, then it must have phonological content in order to ensure roll-up past the verbal root (the 2nd small tree shown above). In the remaining trees, all the heads shown in boldface must have phonological content in order to ensure N+V order. Thus, the larger the IN, the less likely it is that every single functional projection is phonologically specified.

I will now attempt to relate the results above with the observation in Caballero et al. (2008) that N+V order, while more common cross-linguistically, shows a distinct preference for lexicalized forms.Footnote 4 Given the discussion above we expect smaller INs to be more susceptible to N+V order. Likewise, we also expect smaller INs to be more likely to undergo lexicalization. That is, smaller syntactic phrases are more likely become lexicalized than larger ones. Thus, the findings of Caballero et al. are predicted from the proposal put forth here.

This brief section has discussed the general shape of nominals assumed here, allowing for variation among individual languages. It has also show how the preference for N+V order in lexicalized NI constructions arises. The next section discusses N+V order in English gerunds .

5.2 NI in Sierra Popoluca

The first instance of NI I cover in this chapter is fairly prototypical, but underscores a point that will be important in the following chapter. NI in Sierra Popoluca (a Mixe-Zoquen language spoken in Veracruz, Mexico) has N+V order and alternates with non-NI constructions. Consider the following data (de Jong Boudreault 2009: 646), where the nominal kapeel (‘coffee’) can be incorporated or not.Footnote 5

7. | a. | ʔa+kapeljaʔppa | |

ʔa+kapeel=jaʔp-pa | |||

x.abs+coffee=grind-inc | |||

‘I’m going to grind coffee.’ |

b. | ʔi+pinhpa kapeel | ||

ʔi+pinh-pa kapeel | |||

3.erg+pick-erg coffee | |||

‘He collects coffee.’ | |||

As is typical with NI constructions, direct objects, instruments, and locatives can incorporate (de Jong Boudreault 2009: 655).Footnote 6 The IN itself can consist either or a bare root or a root with a nominalizer added (de Jong Boudreault 2009: 648), as shown in 8. Free-standing nominals may be modified by undergoing compounding or by the adjunction of a relative clause; however, the IN may not be modified in this manner (de Jong Boudreault 2009: 657f.), as shown in example 9.

8. | dya ʔa+ʔɨkxjuypa | |

dya | ʔa+ʔɨks-i=juy-pa | |

neg | xabs+dekernel-nzlr=buy-inc | |

‘We didn’t buy corn.’ | ||

9. | a. | ʔam+watpa tum ʔan+suyattɨk | ||

ʔan+wat-pa tum ʔan+suyat=tɨk | ||||

x.erg+make-inc one xpsr+palm=house | ||||

‘I’m going to make a house of palm leaves.’ | ||||

b. | ʔam+pinhpa ʔan+kɨɨpi titzniʔwɨʔɨp | |||

ʔan+pinh-pa ʔan+kɨɨpi | Ø+tɨtz-neʔ-W+ʔpV | |||

x.erg+gather-inc xpsr+wood | 3abs+dry-perf-cmp-rel | |||

‘I’m gathering wood that’s dry.’ | ||||

c. | *ʔa+suyattɨkwatpa | |||

ʔa+suyat=tɨk=wat-pa | ||||

x.abs+palm=house=make-inc | ||||

(‘I build palm houses.’) | ||||

d. | *ʔa+tɨtzkɨɨpipinh-pa | |||

ʔa+tɨtz=kɨɨʔi=pinh-pa | ||||

x.abs+dry=wood=pick-inc | ||||

(‘I’m gathering dry wood.’) | ||||

Finally, de Jong Boudreault (2009: 651ff.) discusses the stress pattern of NI in Sierra Popoluca . She specifically notes that the verbal complex containing the IN, including the various clitics indicating tense and aspectual distinctions, act as a single domain for stress assignment.

The stress patterns that occur on complex predicates composed of a verb and an incorporated noun exhibit the same distribution, showing that these forms make up a single phonological word. (de Jong Boudreault 2009: 653)

Thus, based on the assumptions I made in Section 5.1, the IN does not project up to the higher n that constitutes a stress domain.

I conclude, then, that the IN in Sierra Popoluca is a bare nP, consisting only of a root and a low, categorizing n head. The derivations for 7a and 8 are as follows. The n head selects the bare root as a complement, forming a point of symmetric c-command. This is alleviated by raising the root to SpecnP. The verbal root then selects the nP as a complement, forming another point of symmetry between the two roots, which again is removed by another round of Complement-to-Specifier roll-up. The derivations are shown below for 7a and 8, respectively.

10. | |

|

This concludes this brief section on NI in Sierra Popoluca , which illustrates many canonical properties of NI, including N+V order. In particular, this NI constructions in this language (as well as in Northern Iroquoian as discussed in the previous chapter), constitute a single domain for word-level stress assignment, which I have attributed to the lack of a higher phase-denoting n head in the extended nominal domain. Instead, the IN in this language consists of a bare, category-denoting nP. The root within the nP and the verbal root form a point of symmetric c-command, in violation of the LCA and trigger Complement-to-Spec roll-up. Next, I turn to a discussion of English gerunds .

5.3 English Gerunds

This section analyzes putative NI in English gerunds such as the one found in the following example.Footnote 7

11. | Jerry went elk-hunting the other day. |

I review the properties of these constructions in Section 5.3.1 and follow this by the analysis in Section 5.3.2, where I argue that the syntactic approach to word structure argued for here accounts for properties of these compounds. Specifically, I will show that symmetric c-command between the verbal root and the IN forces Complement-to-Spec roll-up, giving rise to N+V order. I discuss also some of the previous literature on compounding.

5.3.1 Description of NI in English Gerunds

English is not traditionally thought of as having noun incorporation. Examples such as babysit and grocery shop are rare, and are usually backformations from nominalized forms (cf. ‘babysitter’ and ‘grocery shopping’). Noun incorporation into gerunds, however, is highly productive in English as the following examples illustrate.

12. | a. | I went elk-hunting the other day. |

b. | Peter really enjoys teacup-decorating. | |

c. | Alice wants to try ladder-making to keep her wood-working skills sharp. |

The following examples show that the incorporated element (hereafter IN for ease of discussion) cannot contain any plural morphology on the noun, nor can any higher elements such as determiners, quantifiers or adjectives be present.Footnote 8

13. | Impossible Gerunds in English | |

a. | *Will enjoys watches collecting | |

b. | *Will enjoys the watch(es) collecting. | |

c. | *Will enjoys some watches collecting. | |

d. | *Will enjoys a watch collecting. | |

e. | *Will enjoys antique/brass watch collecting. | |

f. | Will enjoys watch-collecting. | |

Furthermore, incorporation (N+V order) is obligatory for these constructions. We do observe instances of a verb followed by a bare noun, but these must be interpreted as mass nouns (see below).

14. | a. | *John enjoys collecting watch. |

b. | *Peter really enjoys decorating teacup. | |

c. | *Alice wants to try making ladder to keep her wood-working skills sharp. |

It appears as though the IN must be a bare singular noun in the sense of Longobardi (1996); however, the following data argue that IN is defective in terms of number and count/mass interpretation. Nouns such as glass in English have both a count and mass interpretation. Examples 15a and 15b show that the interpretation is dictated by the morpho-syntactic environment of the noun. In particular, 15a has only a count interpretation and 15b has only a mass interpretation. In 15c, however, glass can have either interpretation. Furthermore, if it has a count interpretation, it can be understood as either plural or singular, although a plural interpretation is usually preferred for this sentence. Likewise, 15d would be understood as referring to someone who washes many glasses as opposed to a single glass (under the count interpretation); however, 15e could easily be understood as referring to someone who is in charge of washing a single elephant. In other words, the incorporated forms are not specified for number or the count/mass distinction.

15. | a. | Maxwell enjoys washing glasses |

b. | Maxwell enjoys washing glass. | |

c. | Maxwell enjoys glass-washing. | |

d. | Alice is a glass-washer. | |

e. | Alice is an elephant-washer. |

A potential argument against pursuing a syntactic approach to this kind of word formation (and against the single-engine hypothesis in general) resides in the fact that these constructions are often referential islands as discussed by Di Sciullo and Williams (1987). Typical examples include the following.

16. | a. | *John went berry-picking to make jam with them. |

b. | *Kate enjoys teacup-decorating, but she often breaks them. | |

c. | *Siobhan isn’t finished glass-washing yet because there’s a streak on it. |

These contrast with the following clearly syntactic constructions, where pronominal anaphora is licit.

17. | a. | John went to pick berries to make jam with them. |

b. | Kate enjoys decorating teacups, but she often breaks them. | |

c. | Siobhan isn’t finished washing the glass yet because there’s a streak on it. |

The failure of anaphora in the sentences in 16, however, does not have to be attributed to a distinct morphological module that spits out syntactic atoms. It is often the case that bare nouns cannot support anaphora (Stvan 2009).

18. | a. | *Myriam’s still in bed so we can’t make it, yet. |

b. | *Hector is in church because he really admires its architecture. | |

c. | Joe is still in prison, so we’ll have to go there/*to it to visit him. |

Of course not all instances of bare nouns prohibit anaphoric relations, as the following example illustrates.

19. | Raph went to court because he finds it interesting. |

However, as Stvan points out, what the pronoun it refers to is not the court itself (the building or the room) but rather the institutional properties associated with it. Likewise, there are some cases of compounds of this type in English that marginally allow anaphoric reference. To my ear, the following sentence is degraded, but not altogether ungrammatical.

20. | ?I haven’t gone cherry-picking because they’re not ripe, yet. |

The take-home message here is that there is no clear division of labour between syntax and morphology with regard to referential atomicity.Footnote 9

In this section, I have shown that only nouns that are bare of inflectional morphology can, and in fact must, undergo incorporation into a gerund in English, where they are unspecified for the count/mass distinction and are thus ambiguous between the two readings.Footnote 10 Count nouns with any additional morphology and nouns that are obligatorily specified as mass nouns cannot undergo incorporation. The next section proposes a preliminary analysis that accounts for these facts using the theory of Dynamic Antisymmetric Bare Phrase Structure developed in Chapter 2. After the preliminary analysis, I will consider further data and sharpen our analysis.

5.3.2 Analysis

The analysis of the linearization of the incorporated constructions depends crucially on the precise structure of the nominals. I begin the analysis, then, with an in depth discussion on the structure of the IN and of other bare nominal constructions.

I propose that in the incorporated forms discussed here, the gerund merges with a bare noun (that is, a bare nP).Footnote 11 I must assume that the smallest unit that can be incorporated includes a nominalizing head since forms such as student-advisin g, baggage-handle r and toaster-shoppin g. The data from example 13 above show that any DP morphology is ruled out in these constructions. Recall also that the incorporated noun is unmarked for number and the count/mass distinction. Since the incorporated noun is always unspecified for both number and the count/mass distinction, I assume that it does not include Num. Thus, I propose the following structures for the incorporated and non-incorporated forms, respectively.

21. | |

|

This conclusion suggests that the gerund takes a bare noun object in the incorporation structures as in (a), whereas the non-incorporating structures have a full DP object, as in (b). The structures shown in 22 have all elements in their Merge positions.

22. | English Gerund Constructions | |

a. | ||

| ||

b. | ||

| ||

The structure in 22a violates the LCA as V and the root, √, are in a symmetric c-command relation. This violation is resolved by raising the noun to SpecVP, as shown in 23. Since there is no such violation in the second example, no movement is required.

23. | |

|

To see why 15c is ambiguous, while 15a-b are not, consider the structures in 24.

24. | Ambiguity in noun incorporation in English | |

a. | ||

| ||

b. | ||

| ||

As a bare noun, glass in a does not have a number projection, and is thus unspecified for number and the count/mass distinction. Although the noun glass in b looks like a bare noun, I argue that it actually possesses a full DP structure as shown. Crucially, it must possess a Num valued as [mass], since it must receive a mass interpretation here. Thus, the noun glass in b is not ‘bare’ in the sense assumed here. That is, it is not a bare N with no extended nominal projections.

This observation is in accord with the discussion on phonologically null heads in Chapter 2. There it was noted that phonologically null heads must have semantic content. Thus, the pair of constructions, glass-washing and washing glass must have different semantics. I argued that in glass-washing, the noun is a bare N and lacks a Num projection. As such, it is unspecified for a count/mass distinction. In washing glass, on the other hand, glass can only have a mass interpretation.

This section has discussed noun + gerund compounds in English gerunds as an instance of noun incorporation. The word order facts were accounted for using Dynamic Antisymmetry approach to Bare Phrase Structure as proposed in Chapter 2. As before, the order N + V arises by movement of the noun to SpecVP to satisfy the LCA . Since the order V + DP does not violate the LCA, no movement is required. Furthermore, the mass /count ambiguity of N + V compounds with nouns like glass is accounted for by the fact that N + V structures can only arise with bare nouns, which lack a number projection. Thus, no number or count/mass distinction can be specified on N + V structures.

5.4 German Progressives

This section is also discussed in more detail in Barrie and Spreng (2009).

Examples such as those in 25 have been the subject of relatively little previous study beyond brief mentions in the literature (Clahsen et al. 1995 are two notable exceptions; Barrie and Spreng 2009). These compounds, Äpfel-esse n, Mäntel-kaufe n, and Wildschweine-jage n (literally, ‘apples-eating’, ‘coats-buying’, and ‘boars-hunting’), are problematic for theories of word-formation such as Lexical Phonology (Kiparsky 1982; Mohanan 1986), because inflectional morphology (the plural marking) appears inside the compound, and compounding is considered to be a derivational process. The account of these structures presented below, however, follows naturally from the proposal here and the semantic effects of the presence or absence of plural marking in these structures.

25. | German Progressives | ||||||

a. | Ich | bin | beim | Äpfel- | essen. | ||

I | am | at.the | apple.pl- | eat.inf | |||

‘I’m eating apples.’ / ‘I’m busy apple-eating.’ | |||||||

b. | Er | ist | beim | Mäntel- | kaufen. | ||

he | is | at.the | coat.pl- | buy.inf | |||

‘He’s buying coats.’ / ‘He’s busy buying coats.’ | |||||||

c. | Der | Mann | ist | beim | Wildschweine- | jagen. | |

the | man | is | at.the | boar.pl- | hunt.inf | ||

‘The man is boar-hunting.’ | |||||||

This type of construction is limited to the pseudo-irregular plural markers. It is unavailable with the productive /-s/ plural marker found in contemporary German .

26. | *Ich | bin | beim | Auto-s-kaufen |

I | be.1sg | at.the | car-pl-buy.inf | |

(‘I’m buying cars.’) | ||||

At issue here is the plural marking on the first element of the compound. Compounding is considered a derivational process, and traditional wisdom holds that inflectional morphology cannot appear inside derivational morphology; hence the ungrammaticality of the following English compounds with plural marking.

27. | bee-keeper, *bees-keeper; dog-catcher, *dogs-catcher |

Because of this, it has been argued that the irregular plural morphology is derivational rather than inflectional, thus alleviating the problem above (Clahsen et al. 1995; see also Kahnemuyipour 2000; Wiltschko 2004). I address this in the forthcoming analysis; however, I first give some brief evidence on the incorporated status of these constructions.

German has SOV word order in embedded contexts, so before I continue, I must show that the examples in 25 are not simply a case of standard SOV order, but rather are some type of incorporation structure. Consider the following contrast.

28. | …dass | ich | die Äpfel | (in der Küche) | essen möchte. |

…that | I | the apples | (in the kitchen) | eat.inf would.like | |

‘…that we would like to eat the apples (in the kitchen).’ [PP modifies VP] | |||||

29. | Ich | bin | beim | Äpfel | (*in der Küche) | essen. |

I | am | at.the | apples | (in the kitchen) | eat.inf | |

‘I’m busy eating apples (in the kitchen).’ | ||||||

In a standard SOV construction as in 28, adjuncts and adverbials may intervene between the direct object and the verb. In the putative cases of NI such as in 29, no intervening material can appear between the verb and the incorporated object, suggesting a much closer syntactic link between the verb and the IN. See Barrie and Spreng (2009) for additional evidence for the NI status of these constructions.

Compounds where the first element is singular are possible, of course, but there is a change in meaning. Consider the following contrast.

30. | Singular and Plural Compounds in German | ||||||

a. | Ich | bin | beim | Äpfel- | essen. | ||

I | am | at.the | apple.pl- | eat.inf | |||

‘I’m eating apples.’ / ‘I’m busy apple-eating.’ | |||||||

b. | Ich | bin | beim | Apfel- | essen.Footnote 14 | ||

I | am | at.the | apple- | eat.inf | |||

‘I’m busy eating an apple/some apples.’ | |||||||

c. | Er | ist | beim | Mäntel- | kaufen. | ||

he | is | at.the | coat.pl- | buy.inf | |||

‘He’s buying coats.’ / ‘He’s busy coat-buying.’ | |||||||

d. | Er | ist | beim | Mantel- | kaufen. | ||

he | is | at.the | coat- | buy.inf | |||

‘He’s buying a coat/some coats.’ | |||||||

e. | Der | Mann | ist | beim | Wildschweine- | jagen. | |

the | man | is | at.the | boar.pl- | hunt.inf | ||

‘The man is boar-hunting.’ | |||||||

f. | Der | Mann | ist | beim | Wildschwein- | jagen. | |

the | man | is | at.the | boar- | hunt.inf | ||

‘The man is hunting a boar/some boars.’ | |||||||

When the first element in the compound is singular, there is no specification for number. In 30b for example, the speaker could be eating a single apple or many apples. When the first element in the compound is plural, as in 30a, it must be the case that there is a plurality of the objects specified.Footnote 13

Before I present the analysis, I would like to discuss how number is represented in German . Wiltschko (2008) discusses some differences between plural marking in English and Halkomelem and proposes that these differences can be captured is the plural marker in Halkomelem is not a functional head, but rather a root modifier. The following table lists the relevant facts and compares these with plural marking in German.

Wiltschko proposes (roughly) the following two structures, which capture the differences between English and Halkomelem . In English, the plural marker is a functional head that projects and takes nP as a complement, while in Halkomelem, the plural marker is a modifier that does not project and merges directly with an acategorial root.

31. | |

|

These structures account for the facts in Table 5.1 as follows. First, the absence of a plural marker in English is really just the presence of a phonologically null # marker that encodes [singular], while the absence of # in Halkomelem arises simply by the lack of the # modifier. The absence of # leaves the interpretation of number open. The agreement facts arise by # as a functional head entering into an Agree relation with higher elements in the DP. As an optional modifier, # in Halkomelem triggers no such agreement effects. Assuming compounds are created either by √-√ mergers or nP-nP merges (in the case of noun–noun compounds), number in English cannot appear inside compounds since # is a functional category higher than nP. In Halkomelem, however, # merges directly with the root, so it is able to appear inside compound formations. Finally, the fact that # can appear with any category in Halkomelem but is restricted to nouns in English falls out from the fact that # merges with an uncategorized root in Halkomelem but only with an nP in English.

Turning to German , I observe that the regular plural marker /-s/ behaves identically to English; however, the irregular plural markers exhibit one small difference. They behave like the regular plurals and English plurals in all respects except that they can appear inside compounds. Following Acquaviva (2008), I propose that the irregular plural markers (pl in the tree below) are part of n in German, while the regularized German plural, /-s/, instantiates the functional head, #. This is not so surprising in light of other nominalizers such as -age (roughage, baggage, slippage) and -r y (jewellery, basketry, cabinetry) which encode a mass interpretation. Given the association between mass and number described above, admitting a lexical plural encoded by n is actually unsurprising.

32. | German (irrelevant functional projections omitted) |

|

Let us review the properties from Table 5.1 in light of the structure in 32. The regular plural in German has the same properties as the English plural since they both instantiate the functional head, #. The irregular plural, while an n, still triggers an Agree relation via #, thus giving rise to the same kinds of agreement patterns found in English. Unlike the plural marker in Halkomelem , the irregular plural marker in German is restricted to nouns since it’s an n in German rather than a root modifier. Like Halkomelem, however, irregular plurals can appear inside compounds. Assuming compounds (that contain nominal components) are formed by merging bare nPs (Harley 2009), then it is clear why only irregular plurals are admitted in these compounds and why /-s/ is excluded.

These facts above taken together with the structures just discussed suggest the following merged structures for these types of constructions, where [+front] refers to the phonological representation of the plural formation in the German nouns in question.

33. | Underlying Structures for German Compounds | ||

a. | |||

| |||

‘Äpfel-essen’ | |||

b. | |||

| |||

‘Apfel-essen’ | |||

Footnote 14Since the plural marking on the first element of these compounds is semantically interpreted, there must be a low n above N in the compound. In contrast, when the first element of the compound lacks plural marking, there is no specification for number at all. These structures, therefore, lack the number projection altogether. Consequently, both of the structures in 33 violate the LCA . Complement-to-Spec movement therefore takes place, giving the structures in 34.

34. | Spelled-Out Structures for German Compounds | ||

a. | |||

| |||

‘Äpfel-essen’ | |||

b. | |||

| |||

‘Apfel-essen’ | |||

Before leaving this section, I address the issue of compounds with irregular plurals in English mentioned in footnote 9. These kinds of plurals participate in the same kinds of NI constructions discussed here. Consider the following examples.

35. | a. | John thinks that mice-hunting licenses are unnecessary. |

b. | Kate enjoys people-watching at this café. |

As above, I follow Acquaviva’s (2008) suggestion that such lexical plurals (in his terms) derive their plurality from n rather than from #. Thus forms such as mice and people can be bare nPs and do not require a functional number head. They are thus free to undergo NI as described above.Footnote 15

36. | |

|

To conclude this section I have shown that NI constructions in German compounds are compatible only with what I have referred to as irregular plural formation (such as formed by ablaut). Adopting a suggesting by Acquaviva (2008), I assumed that such plurals are represented by a plural n rather than by #. These compounds are formed by merger of the verb with a bare nP, thus giving rise to a point of symmetry and triggering Complement-to-Spec movement. Finally, I showed that compounds with irregular English plurals can be explained with the same structure. Next, I turn a kind of NI construction in Persian .

5.5 Persian ‘Long Infinitive’ Constructions

In this section, I examine the so-called ‘long infinitive’Footnote 16 verb form in Persian and show that the Persian facts fall out naturally from the theory of phrase structure developed here.Footnote 17 Following (Ghomeshi 1997b, 2003) and the theory of the categorization of bare roots by small lexical heads (Marantz 1997, 2001), I assume the structure in 37 for nominals in Persian.

37. | [KP [QP [DP [CardP [ nP [√P ]]]]]] |

Ghomeshi argues that numerals appear in a Card(inality) Phrase in both English and in Persian , and that Persian does not have a NumP. For expository purposes I adopt her analysis here, although nothing crucial hinges on this decision. The KP hosts the definite object marker /râ/. Since this marker does not appear in the constructions under consideration here, it will not appear in the structures illustrated below. As mentioned, I do assume that nouns are comprised of undifferentiated roots that are categorized by n. Note also that n can be overt and, hence, the merger of n and a root always triggers Complement-to-Spec roll-up (data from Kahnemuyipour and Megerdoomian 2002).Footnote 18

38. | a. | bozorg-í |

big-nzlr | ||

‘grandeur’ | ||

b. | divune-gí | |

mad-nzlr | ||

‘madness’ | ||

c. | daan-ésh | |

know-nzlr | ||

‘knowledge’ |

Persian uses the long infinitive in a variety of constructions. The data discussed here are translated as gerunds in English, but are argued to be nominal constructions in Kahnemuyipour (2001).Footnote 19

39. | Long Infinitives with Post-Verbal Complements | ||||||

a. | sima | æz | xundæn-e | ketab | xoš-eš | mi-yad | |

Sima | from | reading-ez | book | good-3sg.cl | cont-come.3sg | ||

‘Sima likes reading books.’ | |||||||

b. | sima | æz | xundæn-e | in ketab | xoš-eš | mi-yad | |

Sima | from | reading-ez | this book | good-3sg.cl | cont-come.3sg | ||

‘Sima likes reading this book.’ | |||||||

c. | sima | æz | xundæn-e | ketab-e æli | xoš-eš | mi-yad | |

Sima | from | reading-ez | book-ez Ali | good-3sg.cl | cont-come.3sg | ||

‘Sima likes reading Ali’s book.’ | |||||||

In example 39, the complement to the long infinitive, xundæ n, can be a full DP, as shown in 39b and 39c.Footnote 20 Example 39a, which appears to contain a bare noun (as argued by Ghomeshi), will be discussed at the end of this section. Contrast the data in 39 with the sentences in 40. When the object is preverbal, only a bare noun is possible.

40. | Long Infinitives with Pre-Verbal Complements | |||||

a. | sima | æz | ketab xundæn | xoš-eš | mi-yad | |

Sima | from | book reading | good-3sg.cl | cont-come.3sg | ||

‘Sima likes reading books.’ | ||||||

b. | *sima | æz | in ketab xundæn | xoš-eš | mi-yad | |

Sima | from | this book reading | good-3sg.cl | cont-come.3sg | ||

(‘Sima likes reading this book.’) | ||||||

c. | *sima | æz | ketab-e æli xundæn | xoš-eš | mi-yad | |

Sima | from | book-ez Ali reading | good-3sg.cl | cont-come.3sg | ||

(‘Sima likes reading Ali’s book.’) | ||||||

While post-verbal object nominals in long infinitives may be either bare nominals or full DPs, the pre-verbal objects must be bare. The structures for 39b and a are given in 41a and b, respectively.

41. | Structures for Persian Long Infinitives | |

a. | ||

| ||

b. | ||

|

The structure in 41a obeys the LCA , and no movement is triggered.Footnote 21 The structure in 41b, however, does violate the LCA and the noun must move to the specifier of the VP as shown in 42.

42. | |

|

Example 39a is still unexplained under the assumption that it is a bare noun as Ghomeshi (2003) argues. Native speakers report almost no difference in meaning between 39a and 40a. The only difference they report has to do with register. Whereas the pre-verbal bare noun is more natural in spoken conversation, the post-verbal noun is more formal and is more characteristic of the written form of the language. Dealing with optionality has always been difficult within a minimalist framework. One could posit a phonologically null [formal/written register] feature heading a functional projection above NP, which would stop Complement-to-Spec movement, allowing the object nominal to remain in its Merge position, but this solution is rather ad hoc and unsatisfying. Ultimately, this question bears significantly on the proposal for identifying empty categories in Chapter 2 – namely, that empty categories must have semantic content. If a null head is posited that has the effect of stopping Complement-to-Spec movement, then there must be some semantic difference between the two forms with and without this head. This is precisely the situation here, where the only difference appears to be register. I leave this problem for future research, noting that it is part of a much larger problem within recent generative linguistics – specifically, the problem of optionality and register variation (see also Cowper and Hall 2003).

Leaving aside the question of optionality, the Persian noun incorporation data presented here are consistent with the Dynamic Antisymmetric approach to Bare Phrase Structure proposed here. Namely, when a verb merges with a bare noun, the noun must raise to SpecVP so as to satisfy the LCA .

5.6 Tamil Noun Incorporation and Coordination

Tamil is an SOV language that has been claimed to have noun incorporation (Steever 1979).Footnote 22 In this section, I look briefly at noun incorporation in Tamil and examine a structure that contains conjoined incorporated nominals. This structure will be shown to follow naturally from the proposal set forth here.

Since Tamil is SOV, noun incorporation is not immediately obvious as it causes no change in word order. However, incorporated nominals can be distinguished from unincorporated ones on the basis of case marking. The examples in 43 show a sentence with a full DP object and a sentence with an incorporated nominal (Schiffman 1999: 97, ex (76); and Steever 1979, respectively). Note that although Steever glosses the incorporated nominal as having nominative Case, he points out that nominative is phonologically unmarked. I therefore follow Steever and assume that the incorporated noun has no case at all.Footnote 23

43. | Tamil NI Constructions | |||

a. | naan | panatt-e | eḍuttu-kiṭṭeen | |

I.nom | money-acc | take.ben.pst.png | ||

‘I took the money for myself.’ | ||||

b. | avan | talai | nimirntān | |

he.nom | head.(nom) | straighten.pst.3msg | ||

‘He straightened his head.’ | ||||

Incorporated nouns in Tamil exhibit many of the core properties of incorporated nouns in other languages. For example, the incorporated noun cannot appear with Case marking, postpositions, adjectives or demonstratives. Tamil does differ in one important way from other languages, in that in Tamil it is possible for conjoined bare nouns to be incorporated, as in 44 (Steever 1979).

44. | avan | pennum | vīṭum | pārkkap | pōkirān |

he.nom | girl.nom.and | house.nom.and | see.inf | go.prs.3 ms | |

‘He is going to look for a bride and a house.’ | |||||

A large number of Tamil nouns can be divided into classes as follows (Schiffman 1999: 25ff.).

45. | a. | Nouns ending in -am | |||||

marram | ‘tree’ | sisṭam | ‘system’ | ||||

duuram | ‘distance’ | ||||||

b. | Nouns ending in -ru | ||||||

aaru | ‘river’ | kayiru | ‘rope’ | ||||

kenaṛu | ‘well’ | sooru | ‘cooked rice’ | ||||

c. | Nouns ending in -ḍu | ||||||

paaḍu | ‘lot, part’ | viiḍu | ‘house’ | ||||

kaaḍu | ‘forest, jungle’ | ||||||

As with many languages, Tamil also sports deverbal nouns with overt nominalizers. I assume, then, that the endings in 45 are nominalizers, the head of nP, and that nouns without one of these endings simply have a phonetically null allomorph. These nominalizers are also present in the IN (Steever 1979: 280f.).

46. | a. | en-nuṭaiya | mukam | malarntatu | |

I.gen | face | bloom.pst.3.nt.sg | |||

‘My face bloomed.’ | |||||

b. | nān | mukam | malarntēn | ||

I.nom | face | bloom.pst.1.sg | |||

‘I experienced pleasure.’ | |||||

As mentioned above, no Case morphology or demonstratives are possible on these forms. I conclude from these observations that the IN in Tamil is a bare nP. As the reader by now can anticipate, the IN is formed by n taking a bare root as a complement, forming a point of symmetric c-command, which is then resolved by raising the root to SpecnP.

47. | |

|

The verbal root then takes the nP as a complement, forming another point of symmetry between the verbal root and the nominal root, giving rise to another round of Complement-to-Spec roll-up.

48. | |

|

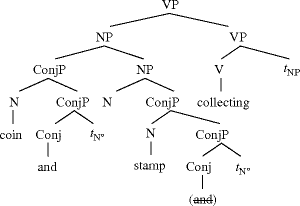

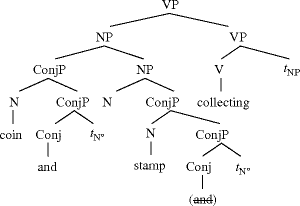

I now turn to the conjoined structure shown in 44. First, I establish some basic assumptions about coordinate structures, and then turn to a discussion of the Tamil data. I adopt Progovac’s (1997) treatment of coordination , with some modifications to make it compatible with Dynamic Antisymmetry. Specifically, I adopt the structure shown in 49, in which each conjunct is the complement of a conjunction head, with which it forms a conjunction phrase (ConjP). The two ConjPs are arguments of an empty head that is of the same type as the conjuncts.Footnote 24

49. | |

|

Example 44 is derived as follows. Each conjunct is independently formed by merging a conjunction with a bare noun, creating an instance of symmetric c-command. The bare noun in each case raises to SpecConjP so as to satisfy the LCA . The two ConjPs then merge with an empty n as in 49. The resulting nP then merges with the verbal root, forming the structure in 50.

50. | |

|

In this structure, however, the verbal root and the nominal root of the first conjunct, shown in boldface in 50, are in a symmetric c-command relation. This is resolved by raising the conjoined NP complex to SpecVP as shown in 51.

51. | |

|

Noun incorporation in Tamil can be understood in terms of the overall analysis proposal here. Specifically, Complement-to-Spec roll-up is triggered by symmetric c-command. The formation of N+V compounds is derived the same way as many of the other compound structures I have shown. The IN is a bare nP in which the root appears in SpecnP, having gotten there as a result of Complement-to-Spec roll-up. The verbal root merges with the nP and the resulting point of symmetric c-command between the verbal and nominal roots triggers another round of roll-up. I also demonstrated that NI with the conjoined structures can also be derived by Complement-to-Spec roll-up triggered by symmetric c-command between the conjunction and the bare noun, and subsequently between the first conjunct and the verb. An obvious question that arises from this discussion is why incorporation of conjoined nominals is allowed in Tamil but in almost no other language that allows noun incorporation. I can only offer the following speculation at this point. Languages differ with respect to the kinds of elements that can be conjoined. Tamil is a language that can conjoin bare nPs. It is quite possible that in other languages elements this small cannot be conjoined. Thus, the absence of conjoined structures inside NI constructions has nothing to do with NI per se, but rather with the properties of conjunction in the language.Footnote 25

5.7 Adverb Incorporation in Blackfoot

I now shift my attention to another kind of incorporation – that of adverb incorporation in Blackfoot , an Algonquian language spoken in Southern Alberta (Canada) and in Montana (USA). As noted above, adverb incorporation has been discussed most extensively in Greek (Alexiadou 1997; Rivero 1992) and also in Chukchi (Spencer 1995). In addition to adverb incorporation, more conventional NI has also been discussed in the Algonquian family (Hirose 2003; Wolfart 1973; Mathieu 2008; Denny 1989). I show here that adverb incorporation in Blackfoot can have the same kind of syntactic analysis as proposed here, despite certain peculiarities in the surface structure. Consider the following examples of adverb incorporation (Beatrice Bullshields, speaker, ex a, b; (Frantz 1991), ex c.).

52. | a. | anná John ikinoowatsi ómi apastaminam | ||

ann-wa John | ikino-owat-yi | om-yi apastaminamm | ||

det-prox John | slow-eat.tr-3.obv | det-obv apple | ||

‘John ate that apple slowly.’ | ||||

b. | anná John ikstonatsikinissaaki | |||

ann-wa John | iik-stonat-ikin-issaaki | |||

det-prox John | deg-deg-slow-wash.dish | |||

‘John washed the dishes really slowly.’ (ibid) | ||||

c. | tsa niitaikkamiyooyi apastaminam | |||

tsa | niit-a-Ikkam-iy-ooyi | apastaminam | ||

q | deg-dur-fast-?-eat.intr | apple | ||

‘How fast does he eat an apple?’ | ||||

The first example shows a simple case of adverb incorporation, where the adverbial element (a pre-verb in Algongquianist terminology) appears immediately to the left of the verbal root. Assuming the adverbial element is selected as a complement to the verb (Larson 2004), 52a is easily derived by complement-to-spec roll-up as discussed throughout this monograph. Example 52b, however, is a bit more problematic for a straightforward roll-up analysis as it contains degree elements (deg) that appear to be part of the adverbial element. Finally, 52c is quite puzzling from the current perspective since the degree element and the adverbial are separated by a durative aspect marker (dur). Constructions such as these at first blush seem to necessitate a morphological template. Nevertheless, I will show that all these forms are derived syntactically by the same underlying structure, shown in 53.Footnote 26

53. | |

|

I will argue here that the Degree Phrase (DegP) – the extended projection of adverbs/adjectives is split or discontinuous in the same way as has been argued for the DP (Lin 2000; Sportiche 1998). Lin (2000) argues for the following structure for object determiner sharing based on data of the following type.

54. | vP > DP > VP > NP |

55. | Mary will eat the pizza on Monday and – tofu on Tuesday. |

The shared determiner in 55 is evidence for coordination below the object DP level. Similar facts are available adverbs and their associated degree expressions. Note that these sentences require a rather specific emphasis to sound natural.

56. | a. | John washes cutlery extremely quickly and washes stemware extremely thoroughly. |

b. | Mary draws trees so efficiently and draws tableaux so quickly that she was often called up to the chalk board. | |

c. | No matter how quickly he runs or swiftly (he) climbs, he will not beat that Sherpa to the top of the mountain. |

Based on these data, I conclude that DegPs are split in the same way and have the following structure.

57. | CP > TP > AspP > vP > DegP > VP >AP |

Let us begin with a cursory examination of the incorporated adverbial elements. As with the nominal and verbal extended domains, the adverbial/adjectival extended domain is argued to contain a categorizing a head (such as English -ish or -al). Taking a look at the following list of adverbial pre-verbs in Blackfoot fails to reveal any kind of predictable pattern or morphological complexity (and Frantz and Russell 1995; data taken from Frantz 1991). I take these data as evidence that the incorporated adverbial element in Blackfoot is a bare root.

58. | Incorporated Adverbial | English Equivalent |

Ikkina | gently, easily | |

iiyik | strong, hard | |

(I)poina | nuisance, frenetic, erratic | |

sok | well, good | |

Ikkam | fast | |

iitsiksist | slow | |

ihta | lucky | |

ikipp | briefly | |

ikkahs | funny, humorous, odd | |

ipahk | bad |

I am now in a position to derive 52c above. The verbal root selects the adverbial root as a complement, and the ensuing symmetric c-command triggers Complement-to-Spec roll-up.

59. | |

|

Now, the internal argument must still be introduced into the derivation, which is accomplished by enlarging the VP shell.Footnote 27 As Blackfoot is a discourse configurational language, I assume that the nominal expressions appear in the left periphery as discussed for Northern Iroquoian in Chapter 2.

60. | |

|

At this point, no more movement triggered by symmetric c-command takes place. It is, however, necessary to show that even when the incorporated adverb is accompanied by degree terms, symmetric c-command still holds between the verbal root and the adverbial. Thus, I continue with the remainder of the derivation for the verbal complex. Next, then, the Deg head associated with the adverb merges with the √P, followed by the v head.

61. | |

|

Once the structure in 61 is formed, the √P raises to SpecvP to capture the traditional V-to-v raising effects (to categorize the root, for instance). From this point, I will ignore the nominal arguments to simplify the derivation. This gives rise to the following structure.

62. | |

|

Finally, the Asp head merges with the vP and the DegP remnant raises to SpecAspP, giving rise to the final structure of the verbal complex.

63. | |

|

This section has shown that adverb incorporation in Blackfoot can be understood partially in terms of the Complement-to-Spec roll-up mechanism proposed in Chapter 2 to break points of symmetry. This section has also shown that the degree elements present in the incorporated constructions are consistent with the approach taken here is I assume that the DegP is split the same way Lin (2000) and Sportiche (1998) have argued for a split DP.

5.8 Conclusion

This chapter has looked briefly at noun+verb compounding in English, German , Persian and Tamil and at adverb incorporation in Blackfoot . Preverbal bare nouns in English gerunds were shown to be unspecified for number and the count/mass distinction, which is taken to be evidence for the lack of a NumP in these constructions. The postverbal nominals in English gerunds were shown to include higher functional projections in the DP domain. In German progressive beim constructions, either the preverbal nouns are bare and are unspecified for number and the count/mass distinction, or they are marked as plural, but are still non-referential. This construction does not allow post-verbal nominals. In Persian, post-verbal nominals are full DPs and pre-verbal nominals are bare Ns. Post-verbal bare nominals are permitted in a formal or written register only. Next, in Tamil, noun incorporation is triggered by the need to satisfy the LCA ; however, I also showed that conjoined nominals can be incorporated by the same mechanism argued for here. Finally, adverb incorporation in Blackfoot was argued to arise by symmetric c-command between the verbal root and the adverbial, which is itself a root. Instances of degree elements in adverb incorporation constructions were argued to arise by split degree phrases. In all cases, incorporation is triggered by the need to satisfy the LCA in accordance with the Dynamic Antisymmetric approach to Bare Phrase Structure proposed in Chapter 2. In the next chapter, I look at a NI constructions in which the order V+N surfaces.

Notes

- 1.

Not included in the discussion here is the set of root modifiers as discussed in Wiltschko (2008) or how adjectives fit in to the structure (Cinque 2010). This section is intended to be a brief introduction to some of the nominal projections used here and to relate nominal structure to linear properties of NI.

- 2.

Note that Harley (2007) has argued for the same distinction based on the presence of passive forms with verbalizing morphology (The butter was clarified, The metal was flattened, etc.)

- 3.

It is often assumed that a mass reading results from the absence of Num (Borer 2005), that is, bare nouns are all inherently mass nouns and are made countable by Num. Following previous work (Barrie and Wiltschko 2010), I assume that mass is not the absence of number, but rather is a marked feature. Note also that the structure of the Num head may be more complex than shown here (Cowper 2005; Cowper and Hall 2009; Harley and Ritter 2002; Harbour 2007).

- 4.

Thanks to Jan-Wouter Zwart for pressing this matter.

- 5.

The following abbreviations are used in the Sierra Popoluca data: abs – absolutive; cmp – completive; erg – ergative; inc – incompletive; neg – negative; nzlr – nominalizer (source document uses nom); x – 1st person exclusive. + is used to mark clitic boundaries.

- 6.

de Jong Boudreault notes that agent incorporation is not to be found in any of the texts she has worked with, but has found one example under elicitation, suggesting its rarity.

i.

ʔa+tzaanywás

ʔa+tzaanyi=was-W

x.abs+snake=bit-cmp

‘I was bitten by a snake.’

I leave the implications of this to future research, but I do note that the passive translation (as opposed to ‘A snake bit me.’) suggests that the snake is less agentive and perhaps enters the derivation as an oblique argument within the DP (such as an instrument). It is also reminiscent of English NI-type compounds such as horse-drawn carriag e.

- 7.

As a referee notes, this form is typically restricted to gerunds. Unfortunately, I have no insight to offer here as to why this should be so. Under the current proposal, NI takes place before the entire unit is categorized. That is ‘elk-hunting’ is formed by the merger of the root ‘hunt’ with the nP ‘elk’. This complex form is subsequently built up into a gerund form. While acknowledging that this fact about NI in English gerunds still requires an explanation, the author has heard the following spontaneous utterances from non-linguist native speakers of English.

‘I haven’t cherry-picked in a long time.’ (referring to the act of picking cherries off a tree)

‘We’re going out to Calgary this weekend to house-hunt.’

- 8.

Forms with irregular plurals such as mice-huntin g and people-watchin g are possible in English. We address these in the section on German compounds.

- 9.

See Harley (2008) for additional arguments along these lines dealing with denominal verbs.

- 10.

Pragmatics or semantics may force one interpretation over the other, but crucially, this is not a property of the incorporated noun. For example, in the phrase chicken-sorting a count interpretation is forced because the act of sorting requires discrete entities. Likewise, in the phrase, garlic-mashing, a mass interpretation is strongly preferred because of what is involved in the act of mashing.

- 11.

This is a potential point of confusion. The term ‘bare noun’ is often used to refer to a noun without any overt nominal morphology attached to it (as in they drank water). I am using the term here to refer to an nP without any extended nominal functional projections, either overt or covert. In the phrase they drank water, the noun ‘water’ is ‘bare’ in the sense that is has no overt morphemes; however, it is assumed to project the same set of functional categories as any other non-incorporated object.

- 12.

For some speakers this sentence sounds strange since this construction is used for extended activities where the participant is off busy doing something (Bettina Spreng, pc). Since eating an apple is not typically a time-consuming event, this sentence may sound odd.

- 13.

There are a few exceptions to this generalization. The forms Bären-schiessen (‘bear-shooting’) and Hirsche-jagen (‘deer-hunting’) can appear in the plural only and are underspecified for number. I suggest that these forms are stored as idioms.

- 14.

I represent the plural morpheme as a floating [+front] feature because of the umlaut on the first vowel.

i.

Apfel → Äpfel [apfəl] → [ɛpfəl]

ii.

Mantel → Mäntel [mantəl] → [mɛntəl]

- 15.

An unanswered question here is exactly how the form mice arises in the derivation. Unlike the German plurals, there is not really enough regularity of any kind in English irregular plurals to permit a simple feature such as [+front]. I have represented mice as a root (distinct from mouse) that occurs only in the context of an n with an abstract plural feature. One possibility is that mice is inserted post-syntactically in the label of nP along the lines of Béjar (2004), but I leave the details to future research.

- 16.

- 17.

- 18.

There is a potential wrinkle here with the view that the forms in 38 consist of a bare root and a nominalizer . Arsalan Khanemuyipour (p.c.) informs me that in 38c, for example, the root is actually the present tense form of the stem (as opposed to the past tense stem). Under the assumption that present tense is the unmarked tense, it is unsurprising that the present tense stem is used in the nominalized constructions. I continue to assume that these forms consist of bare roots plus a nominalizer.

- 19.

In fact, Cowper (1992) has argued that the corresponding English constructions are nominal, too. I also leave aside the issue of word order in Persian . Persian is SOV (though it has prepositions instead of postpositions and post-verbal clausal complements). Given the approach here (specifically Antisymmetry), the underlying order must be SVO. Since this is the observed order in the non-NI forms under consideration here, I simply leave this issue aside. See Karimi (2005) for some discussion on Persian word order and Antisymmetry.

- 20.

Note that the ezafe vowel, ez, is arguably not part of the syntactic structure. See Ghomeshi (1997a) for a detailed discussion of the ezafe vowel in the syntax of Persian nominal constructions.

- 21.

I follow Ghomeshi (1997b) and assume that the ezafe vowel is inserted phonologically. See also footnote 22.

- 22.

- 23.

The presence of two ‘nominative’ DPs is the source of an earlier claim that Tamil violates the putative universal that sentences cannot have more than one subject. Steever argues that these sentences do not have two subjects, but rather that the nominal closer to the verb is actually incorporated and does not bear true nominative Case. In 43b I place the nom designator in brackets to highlight this claim, even though Steever glosses the IN as having nominative Case throughout.

- 24.

This difference between this approach and Progovac’s original approach is that Progovac right-adjoined each ConjP to an empty category of the same type as the conjuncts.

- 25.

English does have some examples of conjoined incorporated nouns such as coin-and-stamp-collectin g. In this case, is would appear we have the following structure, where N represents nP to save space.

i.

In this structure, collecting and coin c-command each other, triggering the NP to raise to SpecVP. Still unexplained here (and in coordinating constructions in general) is the choice of which Conj to pronounce. In the structure given here, the higher conjunction is pronounced at PF (as indicated by the strikethrough of the lower conjunction).

- 26.

Note that although I assume undifferentiated roots here as throughout (Marantz 1997), I use the labels V and A in the schematic trees to avoid confusion.

- 27.

I represent the object as a bare NumP as non-specific nominals fail to trigger transitive agreement on the verb. I assume that a full DP is required for transitive agreement.

References

Abney, Stephen. 1987. “The English Noun Phrase and its Sentential Aspect.” PhD diss., MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Acquaviva, Paolo. 2008. Lexical Plurals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Alexiadou, Artemis. 1997. Adverb Placement: A Case Study in Antisymmetric Syntax. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Barrie, Michael, and Bettina Spreng. 2009. “Noun Incorporation and the Progressive in German.” Lingua 119 (2):374–88.

Barrie, Michael, and Martina Wiltschko. 2010. “How To Be a Mass and Other Cases of Nominal Aspect.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Linguistic Association, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, May 29–31.

Béjar, Susana. 2004. “Syntactic Projections as Vocabulary Insertions Sites.” Paper presented at the NELS 35, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT.

Borer, Hagit. 2005. Structuring Sense, Volume 1: In Name Only. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Caballero, Gabriela, Michael J. Houser, Nicole Marcus, Teresa McFarland, Anne Phycha, Maziar Toosarvandani, Suzanne Wilhite, and Johanna Nichols. 2008. “Nonsyntactic Ordering Effects in Syntactic Noun Incorporation.” Linguistic Typology 12 (3):383–421.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2010. The Syntax of Adjectives: A Comparative Study. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Clahsen, Harald, Gary Marcus, Susanne Bartke, and Richard Wiese. 1995. “Compounding and Inflection in German Child Language.” In Yearbook of Morphology, edited by Geert Booij, and Jaap van Marle, 115–142. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Cowper, Elizabeth. 1992. “Infinitival Complements of Have.” Canadian Journal of Linguistics 37 (2):115–36.

Cowper, Elizabeth. 2005. “A Note on Number.” Linguistic Inquiry 36 (3):441–55.

Cowper, Elizabeth, and Daniel Currie Hall. 2003. “The Role of Register in the Syntax-Morphology Interface.” In Annual Meeting of the Canadian Linguistic Association, edited by Sophie Burelle, and Stanca Somesfalean. http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/~cla-acl/2003/Cowper-Hall.pdf

Cowper, Elizabeth, and Daniel Currie Hall. 2009. “Where—and What—Is Number?” In The 2009 Annual Conference of the Canadian Linguistic Association, edited by Frédéric Mailhot. http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/~cla-acl/actes2009/CLA2009_Cowper_Hall.pdf

de Jong Boudreault, Linda J. 2009. “A Grammar of Sierra Popoluca (Soteapanec, a Mixe-Zoquean Language).” PhD diss., University of Texas, Austin.

Denny, J. Peter. 1989. “The Nature of Polysynthesis in Algonquian and Eskimo.” In Theoretical Perspectives on Native American Languages, edited by Donna Gerdts, and Karin Michelson, 203–58. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Di Sciullo, Anna Maria, and Edwin Williams. 1987. On the Definition of Word. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Frantz, Donald G. 1991. Blackfoot Grammar. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Frantz, Donald G., and Norma Jean Russell. 1995. Blackfoot Dictionary of Stems, Roots, and Affixes. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Ghomeshi, Jila. 1997a. “Non-Projecting Nouns and the Ezafe Construction in Persian.” Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 15 (4):729–88.

Ghomeshi, Jila. 1997b. “Topics in Persian VPs.” Lingua 102 (2–3):133–67.

Ghomeshi, Jila. 2001. “Control and Thematic Agreement.” Canadian Journal of Linguistics 46 (1/2):9–40.

Ghomeshi, Jila. 2003. “Plural Marking, Indefiniteness, and the Noun Phrase.” Studia Linguistica 57 (2):47–74.

Harbour, Daniel. 2007. Morphosemantic Number: From Kiowa Noun Classes to UG Number Features. Amsterdam: Springer.

Harley, Heidi. 2007. External Arguments: On the independence of Voice° and v°. Tromsø, Norway, April 12–14, 2007

Harley, Heidi. 2008. Bare Roots, Conflation and the Canonical Use Constraint. University of Lund, Lund, Sweden, February 5–6, 2008

Harley, Heidi. 2009. “Compounding in Distributed Morphology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Compounding, edited by Rochelle Lieber, and Pavol Štekauer, 129–44. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harley, Heidi, and Elizabeth Ritter. 2002. “Person and Number in Pronouns: A Feature-Geometric Analysis.” Language 78 (3):482–526.

Hirose, Tomio. 2003. Origins of Predicates: Evidence from Plains Cree. London: Routledge.

Hualde, Jose Ignacio. 1992. “Metaphony and Count/Mass Morphology in Asturian and Cantabrian Dialects.” In Theoretical Analyses in Romance Linguistics, edited by Christiane Laeufer, and Terrell A. Morgan, 99–114. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Kahnemuyipour, Arsalan. 2000. “On the Derivationality of Some Inflectional Affixes in Persian.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Linguistics Society of America, Chicago, IL.

Kahnemuyipour, Arsalan. 2001. “On Wh-Questions in Persian.” Canadian Journal of Linguistics 46 (1/2):41–61.

Kahnemuyipour, Arsalan, and Karine Megerdoomian. 2002. “The Derivation/Inflection Distinction and Post-Syntactic Merge.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Linguistic Association, Toronto, ON.

Karimi, Simin. 2005. A Minimalist Approach to Scrambling. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kiparsky, Paul. 1982. “Lexical Morphology and Phonology.” In Linguistics in the Morning Calm, edited by Ik-Hwan Lee, 3–91. Seoul: Hanshin.

Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju. 2003. The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Larson, Richard K. 2004. “Sentence Final Adverbs and “Scope”.” In Proceedings of NELS 34, edited by Keir Moulton, and Matthew Wolf, 23–43. Amherst, MA: GLSA Publications.

Lin, Vivian. 2000. “Determiner Sharing.” In Proceedings of WCCFL 19, edited by Roger Billerey, and Brook Danielle Lillehaugen, 274–87. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Longobardi, Giuseppe. 1996. “The Syntax of N-Raising: A Minimalist Theory.” OTS Working Papers, Utrecht, 1–151.

Marantz, Alec. 1997. “No Escape from Syntax: Don’t Try Morphological Analysis in the Privacy of Your Own Lexicon.” University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics 4 (2):201–25.

Marantz, Alec. 2001. “Words.” Paper presented at the 20th West Coast conference on Formal Linguistics, University of Southern California, February 23–25, 2001.

Marvin, Tatjana. 2003. “Topics in the Stress and Syntax of Words.” PhD diss., MIT, Cambridge, MA.

Mathieu, Éric. 2008. “Word Formation as Phrasal Movement: Evidence from Ojibwe.” Paper presented at the NELS 39, Cornell University, November 5–7.

Megerdoomian, Karine. 2008. “Parallel Nominal and Verbal Projections.” In Foundational Issues in Linguistic Theory: Essays in Honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, edited by Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero, and Maria Luisa Zubizaretta, 73–103. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Miner, Kenneth L. 1989. “A Note on Noun Stripping.” International Journal of American Linguistics 55 (4):476–77.

Mithun, Marianne. 2000. “Incorporation.” In Morphology, edited by Geert Booij, Christian Lehmann, and Joachim Mugdan, 916–28. Berlin: deGruyter.

Modarresi, Fereshteh, and Alexandra Simonenko. 2007. “Quasi Noun Incorporation in Persian.” In The Oxford Postgraduate Linguistics Conference: http://www.ling-phil.ox.ac.uk/events/lingo/proceedings.htm

Mohanan, K. P. 1986. The Theory of Lexical Phonology. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Newell, Heather. 2008. “Aspects of the Morphology and Phonology of Phases.” PhD diss., McGill University, Montreal, QC.

Penny, Ralph, J. 1970. “Mass-Nouns and Metaphony in the Dialects of North-Western Spain.” Archivum Linguisticum 1:21–30.

Progovac, Ljiljana. 1997. “Slavic and the Structure for Coordination.” In Formal Approaches to Slavic Linguistics, 1996, edited by Martina Lindseth, and Steven Franks. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan Slavic Publications.

Ritter, Elizabeth. 1992. “Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Number Phrase.” Canadian Journal of Linguistics 37 (2):197–218.

Ritter, Elizabeth. 1993. “Where’s Gender?” Linguistic Inquiry 24 (4):795–803.

Rivero, Maria-Luisa. 1992. “Adverb Incorporation and the Syntax of Adverbs in Modern Greek.” Linguistics and Philosophy 15 (3):289–331.

Schiffman, Harold F. 1999. A Reference Grammar of Spoken Tamil. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Spencer, Andrew. 1995. “Incorporation in Chukchi.” Language: Journal of the Linguistic Society of America 71 (3):439–89.

Sportiche, Dominique. 1998. Reconstruction and Constituent Structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Steever, Sanford B. 1979. “Noun Incorporation in Tamil, or What’s a Noun Like You Doing in a Verb Like This?” In Papers from the Regional Meetings. Chicago, IL: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Steever, Sanford B. 1998. The Dravidian Languages. London: Routledge.

Stvan, Laurel Smith. 2009. “Semantic Incorporation as an Account for Some Bare Singular Count Noun Uses in English.” Lingua 119 (2):314–33.

Travis, Lisa de Mena. 1992. “Inner Tense with NPs: The Position of Number.” In Proceedings of the Canadian Linguistics Association Annual Conference, edited by Carrie Dyck, Jila Ghomeshi, and Tom Wilson, 329–46.

Valois, Daniel. 1991. “The Internal Syntax of DP.” PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, CA.

van Geenhoven, Veerle. 1998. Semantic Incorporation and Indefinite Descriptions: Semantic and Syntactic Aspects of Noun Incorporation in West Greenlandic. Dissertations in Linguistics. (DiLi). Stanford, CA: Center for the Study of Language and Information.

Wiltschko, Martina. 2004. “Expletive Categorical Information: A Case Study of Number Marking in Halkomelem Salish.” In Northeast Linguistics Society (NELS). Amherst, MA: GLSA Publications.

Wiltschko, Martina. 2008. “The Syntax of Non-inflectional Plural Marking.” Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 26 (3):639–94.

Wolfart, H. Christopher. 1973. “Plains Cree: A Grammatical Study.” American Philosophical Society Transactions, New Series 63 (5).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Barrie, M. (2011). Noun Incorporation and Its Kind in Other Languages. In: Dynamic Antisymmetry and the Syntax of Noun Incorporation. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, vol 84. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1570-7_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1570-7_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-1569-1

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-1570-7

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)