Abstract

The first record of the American blue crab Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 from Europe was collected in 1900 on the Atlantic coast of France. Subsequently specimens were detected in the North Sea (1932), Mediterranean Sea (1949, but probably as early as 1935), Baltic Sea (1951), Black Sea (1967), and possibly in the Sea of Azov (1967). It seems that multiple independent introductions may have taken place with ballast water is the most likely introduction vector. In some cases accidental release from holding tanks or intentional release from fishery activities could be involved. Several records may likely be explained also by long-distance migrations of specimens from their primary locations of introduction. But not every introduction was successful over time. Among insufficient habitats and environmental pollution, too low water temperatures seem an important factor for the non establishment of C. sapidus especially in northern Europe and in the Black Sea. The American blue crab may benefit from global warming, and there is increasing concern about its ecological and economic impacts. For a definitive assessment an adequate quantification and comparison of documented and potential effects of C. sapidus is of considerable importance. Such ambitious task has not been carried out so far.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

The American blue crab Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896, is native to the Atlantic coast from Nova Scotia, Canada to northern Argentina (Food and Agriculture Organization 2007). Records north of Cape Code, Massachusetts, however, occur only during favourable warm periods (Williams 1984). It is most abundant from Texas to Massachusetts Bay, where it forms the base of an important commercial and recreational fishery (Hill et al. 1989). The species lives in estuaries and marine embayments from the water’s edge to approximately 90 m, mainly in the shallows to depth of 35 m, on muddy and sandy bottoms. It is extremely euryhaline. Within the native range crabs occupy water ranging from a near-ocean salinity of 34 psu to freshwater in rivers as far as 195 km upstream from the coast. After mating in the upper reaches of estuaries, females move seawards or to nearshore coastal waters to spawn (Hill et al. 1989).

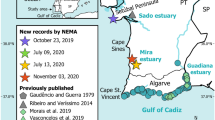

Its presence in high numbers next to well travelled shipping routes made C. sapidus a candidate for passive dispersal with shipping. As it is a highly valued seafood, it is conceivable that C. sapidus may be intentionally released to form the nucleus of a breeding population of commercial value. Therefore it may have not been a complete surprise to learn that over the past century blue crabs have been observed in Africa, Asia, Europe, far from their native range (e.g., Williams 1974; CIESM 2008). Despite the increasing spread and rising invasion rate, no comprehensive review of the introduction of C. sapidus exists. A project inventorying invasive species, funded by the European Commission (DAISIE 2009), attempted to document the species spatial and temporal spread across Europe in the form of a searchable database. However, the data was limited and insufficient. We aim in this chapter to review the presence of C. sapidus in European waters and surrounding seas (Fig. 1). The species’ possible origin, vectors of introduction, and its potential as an invasive are discussed.

2 Spatial and Temporal Trends in European and Adjacent Waters

2.1 Atlantic Ocean (Inclusive of English Channel)

France Bouvier (1901) was the first to record C. sapidus in Europe. A port official had found, probably in 1900, a live adult male crab in a freshwater basin inside the harbour of Rochefort on the Atlantic coast of France. Not until 60 years later, was a second adult male specimen collected nearby, by a plaice fisherman, in the outer estuary of the River Gironde near Verdon (Amanieu and Le Dantec 1961). Most French records of the species stem from the Seine estuary, Normandy: in the summer of 1973 or 1974 a specimen was observed at Deauville (Vincent 1999), a few specimens were captured by fishermen in the outer Seine estuary and two were collected live in Le Havre harbour (Vincent 1986, 1999), in October 1996 a dead specimen was washed ashore at the Cap de la Hève (Vincent 1999). The most recent record dates back to September 2003 when a specimen was caught near Courseulles-sur-mer (ICES WGITMO 2004). All the above mentioned specimens, but one of indeterminate sex, were males. Few female crabs were recorded: a single specimen was captured at Malo-les-Bains, near Dunkirk, on 17 October 1984, and in September and October 1995 two females, one ovigerous, were collected nearby at Gravelines and Bray-Dunes respectively (Vincent 1999). Between 1995 and 2001 several adult specimens were collected along the coast of northern France, including ovigerous females, but no details were kept (ICES WGITMO (2001)). Because of the irregular and sporadic records, C. sapidus is considered not to have established a population along the French Atlantic coast, and the rare occurrence of ovigerous females near the Belgian border could be ascribed to established populations there (see following).

Great Britain The first British record of C. sapidus was trawled off Littlestone-on-Sea, Kent, in September 1975 (Ingle 1980, Clark 1984). On 24 February 2010 a live adult female crab was caught in the Fal estuary, south of Turnaware point (P.F. Clark pers. comm.). Other records from the UK were collected from the North Sea (see following).

Portugal The only known record of the species is an adult female specimen collected in January 1978 in the outer estuary of the Tajo at Paco de Arcos, near Lisbon (Gaudencio and Guerra 1979).

Spain The species was mentioned as occurring in the estuary of the Guadalquivir, on the southern Atlantic coast of Spain (WWF/Adena 2002). It seems that the species has become established in the Guadalquivir estuary since 2005, though no details were given (ICES WGITMO 2007).

In northern Spain an immature female specimen was collected on 22 September 2004 from the grille of the intake cooling water pipe at a power plant at Port of El Musel, Gijón (Cabal et al. 2006).

2.2 North Sea

Belgium The first Belgian record of C. sapidus dates from November 1981. A dead specimen was discovered in the cooling water system of a chemical plant at Antwerp which water originate in the River Scheldt (Adema 1991). The first live specimen was found by a child on August 1984 at Knokke-Heist, near the harbour of Zeebrugge (Rappé 1985). In October 1993 a male specimen was collected in the artificially heated waters of the cooling system of the nuclear plant at Doel on the inner Scheldt estuary (Van Damme and Maes 1993). At the same site a single blue crab was detected between July 1994 and June 1995 (Maes et al. 1998).

Between 1995 and 2001 several crabs, including ovigerous females, were found in Belgian coastal waters, though no additional information is given (ICES WGITMO 2001). In November 2002 an adult male crab was fished off Oostende (ICES WGITMO 2003). Between August and November 2004 an adult male and three female specimens, one of which ovigerous, were caught by shrimp fishermen in the Western Scheldt estuary and transferred to public aquaria (Kerckhof and Haelters 2005). Between July and October 2006 at least seven female specimens including several ovigerous specimens were brought in by shrimp fishermen. They related that additional specimens have been fished, and indeed, several dried specimens are on exhibit in the Nieuwpoort fishmarket (ICES WGITMO 2007, F. Kerckhof pers. comm.). It seems plausible that since the 1990s a resident population exists in the coastal waters and in the Scheldt estuary (ICES WGITMO 2001; Kerckhof et al. 2007), perhaps connected with the established population in the Dutch part of the Western Scheldt estuary (see following).

Germany The first record from Germany was a specimen caught in the outer estuary of the Elbe near Cuxhaven in September 1964 (Kühl 1965). Several records stem from the Weser estuary: a specimen was caught, probably in 1965, near Blexen, between the outer and inner Weser estuary (Nehring et al. 2008), two specimens were found in 1990 in the cooling water inlet of a power station at Bremen harbour on the inner Weser estuary (Nehring et al. 2008), and in November 1998 an adult was caught in an eel pot together with several Chinese mitten crabs (Eriocheir sinensis H. Milne Edwards, 1853) in the inner part of the Weser estuary (Geiter 2000). All but one crab of undetermined sex were male crabs. The first recorded adult female was caught by a shrimp fisherman in the outer Weser estuary on 20 July 2007 (Nehring et al. 2008). The most recent female specimen was collected on 26 May 2008 by a shrimp fisherman in the East Frisian Wadden Sea at the Accumersieler Balje, the tidal inlet between the German islands Baltrum and Langeoog (Fig. 2). The female, kept in a public marine aquarium at 30 psu and 19°C, laid on the14th day millions of eggs, which hatched after 2 weeks (Nehring and van der Meer 2010). As a successfully reproducing population had not been observed so far, C. sapidus is considered as non established alien species (Gollasch and Nehring 2006; Nehring and van der Meer 2010). Crabs found on the German North Sea coast may stem from established populations of the species in the Netherlands (see following).

Great Britain On 18 August 1982 a male was collected by an angler from Dunham Bridge, approximately 38 miles up the River Trent, a tributary of the Humber (Clark 1984). A single specimen was caught, probably in 2000, by an eel fisherman in the River Thames near Erith (P.F. Clark pers. comm.).

The Netherlands The first Dutch records consist of two female specimens, one taken on 10 September 1932 in the River Zaan near Zaandam, northwest of Amsterdam, and the other collected in December 1934 in Amsterdam harbour (Den Hartog and Holthuis 1951). The authors mention two boiled specimens, male and female, washed ashore near Vlissingen on August 1950. A live specimen was collected from the Noordzeekanaal at Nauerna in July 1951, and four dead specimens washed ashore at Schiermonnikoog on 7 May 1967 (Holthuis 1969). Both live and dead crabs have been found sporadically in Dutch coastal waters over the next decades: dates, locations, sex and conditions are summarized by Adema (1983, 1991), Craeymeersch and Kamermans (1996), ICES WGITMO (2000, 2001, 2006) and Wolff (2005). It should be noted that ovigerous females were found in 1982, 1999 and 2000. In the ports of Amsterdam, Hoek van Holland and Rotterdam specimens of C. sapidus are recorded each year since 1995, though detailed information is lacking. In 2002 a first blue crab was observed by a diver in the Eastern Scheldt estuary near the storm surge barrier (Anonymous 2003). The frequency and the increased number of records, including ovigerous females, suggest that C. sapidus has become established in the Western Scheldt estuary and adjacent waters as well as the Noordzeekanaal between Amsterdam and the North Sea since the 1990s (ICES WGITMO 2000,ICES WGITMO 2001;Wolff 2005). It is likely the population in the Western Scheldt estuary is part of the established population found in the Scheldt estuary and coastal waters of Belgium. The recent occasional records in the Dutch Wadden Sea and the German North Sea coast could be connected with the established population in the Noordzeekanaal.

2.3 Baltic Sea

Denmark Only two records are known from Danish waters: on 20 September 1951 a female was captured by a plaice net northeast of Copenhagen and kept alive for a year in a public aquarium (Wolff 1954), in 2007 an adult male was caught off Skagen, Northern Jutland, between the Kattegat and the Skagerrak (Tendal and Flintegaard 2007).

2.4 Mediterranean Sea

Albania The first record dates to 2008: a female crab was found in Patok Lagoon, near the border with Montenegro (White et al. 2009). Referring to pers. comm. with local fishermen, C. sapidus was probably introduced in 2006 (Beqiraj and Kashta 2010). In the first years the species was not abundant, while during 2009 its abundance was highly increased. During April and October 2009 a daily average of 40–50 individuals were caught in a 300 m gillnet (Beqiraj and Kashta 2010). The authors conclude that there is a self-maintaining population in Patok Lagoon.

Croatia The first record was a male crab collected from a fish trap set in the Neretva estuary in October 2004, another specimen was collected by gillnet in the same location on 6 December 2006. On 15 October 2004 two females and two males were caught in a hypersaline lagoon on the Pelješac peninsula near Ston (Onofri et al. 2008). The authors suggest sufficient information has not been gathered yet to deduce whether C. sapidus has established a population in the area.

Cyprus Demetropoulos and Neocleous (1969) reported occasional occurrence of the crab along the southeast coast of Cyprus, between Cape Andreas and Cape Greco. Lewinsohn and Holthuis (1986) reported one preserved and two live specimens from Cypriot waters, though no dates or localities were given. No other Cypriot records of this species are known.

Egypt Banoub (1963) reported that blue crabs had been first recorded in the 1940 fisheries statistics of Lake Menzela. However, at that time the catches of C. sapidus had not been split from those of swimming crabs of the Portunus pelagicus species complex, and this confusion has persisted in literature (Williams 1974; Lai et al. 2010). The first confidently identified specimens of C. sapidus were collected in Lake Edku in January 1960 (Banoub 1963). In the 1960s it was mostly caught by fish-traps in the brackish Nile delta lakes and only rarely from the adjacent coast (Ramadan and Dowidar 1972). Their annual catch peaked in 1964 (2,413 tons), subsequent catches plummeting: in 1971 only 8 tons were fished, possibly because the construction of the High Dam at Aswan altered the hydrology of the delta (Ramadan and Dowidar 1972). The decline worsened in the following years, but has since the 1980s partially recovered (Abdel-Razec 1987). Though no records have been published in recent years, it is believe that population persists.

France A single record is known from the French Mediterranean coast: on 1 October 1962 a single specimen was found in the Etang de Berre, near Marseille (CIESM 2008; H. Zibrowius pers. comm.).

Greece A survey among fishermen implied that at least since 1935 the crabs have occurred in the Gulf of Thessaloniki, and that since 1952 they have been sold regularly at the markets of Athens, Kavala, Piraeus and Thessaloniki, but catches have dwindled since 1963 probably due to overfishing and pollution (Georgiadis and Georgiadis 1974). In 1971 a single dead specimen was found in the Gallikos estuary, and nearby a fisherman caught 4 kg blue crabs. In the region of Alexandropolis and the lagoons of Thraki the crabs disappeared between 1978 and 1982, probably for similar reasons (Enzenroß et al. 1997). However Serbetis (1959) maintains that C. sapidus was first observed in 1948 in the Peneios estuary, in the Gulf of Thessaloniki, and has spread only since 1954 in the northern Aegean Sea. The first confidently identified specimens, an adult and a juvenile female, were collected on 29 June 1959 near Porto Lago harbour, on the Aegean coast (Holthuis 1961). Between March 1963 and May 1965 many live and dead specimens were observed in the estuaries and the lagoons of the northern Aegean Sea (Kinzelbach 1965). Unlabelled and badly preserved specimens were reported from a collection on Rhodes (Kinzelbach 1965), and a single unconfirmed record from the southern Aegean Sea exists (Kevrekidis and Galil 2003).

Specimens infested with a rhizocephalan parasite were rejected by the housewives shopping for seafood (Kinzelbach 1965). Boschma (1972) identified the parasite, without examination, as Loxothylacus texanus Boschma, 1933, known from the American populations.

Though the population of C. sapidus has been decimated, it is considered as established especially in the northern Aegean Sea (Pancucci-Papadopoulou et al. 2005).

Israel The first Israeli records, three males and a female, were collected on November 1951 in the Heftsi-Bah estuary, near Hadera (Holthuis and Gottlieb 1955). These authors reported the finding of many specimens from the Na’aman estuary, near Acre, the Dalia estuary, near Tantura, and in Haifa Bay, and proposed that their abundance and the presence of ovigerous females indicate that C. sapidus has become established along the coast. In the following decades blue crabs had been regularly collected along the Israeli coast near estuaries and in brackish fish ponds (Snovsky and Galil 1990). Analysis of zooplankton samples collected along the coast between the years 1961 and 1968 showed blue crab larvae peak in April and are less abundant in May, July and September (Galil 1993). The larval contingent clearly demonstrates that C. sapidus has indeed assimilated within the local coastal fauna.

Though unable to reproduce in freshwater, the crab has been reported from inland water: a single adult specimen was collected by gillnet in the Sea of Galilee on October 1989 (Snovsky and Galil 1990). The authors assume that its occurrence in the freshwater lake was an accidental introduction with mugilid juveniles transported from the Mediterranean Sea to stock the lake.

Italy The first record of C. sapidus in the Mediterranean Sea is commonly ascribed to Giordani Soika (1951) (e.g., by Enzenroß et al. 1997; CIESM 2008). That author reported two specimens: an adult female collected off Caorle, north of Venice in December 1949, and a adult male from the lagoon of Venice, near Fusina, collected on 10 October 1950; he identified as Neptunus pelagicus A. Milne-Edwards, 1861 (syn. Portunus pelagicus (L.)), but which have been later identified by Holthuis (1961) based on Giordani Soika’s description and illustration as C. sapidus. Mizzan (1993) identified two specimens of C. sapidus labelled as N. pelagicus he found in the zoological collections of the Natural History Museum of Venice as those originally recorded by Giordani Soika. However, the sampling sites and dates of the specimens differ from those stated by Giordani Soika (1951) the female crab was collected near Marina di Grado on 4 October 1949, and the male in Venice lagoon on 8 October 1950. Since that female was collected earlier than the one cited by Giordani Soika, it seems that the first confirmed record of the Mediterranean should be ascribed to Mizzan (1993), though there are claims to its presence in the Aegean as early as 1935. Additional specimens were collected in the lagoon in October 1991 and 1992 (Mizzan 1993), though not in the following years, so Mizzan (1999) concluded that C. sapidus has not established a population there. In the collections of the Museum, Mizzan (1993) also found out a male of C. danae Smith, 1869 which is native to Western Atlantic from Florida to Argentina (Rathbun 1930). It had been caught in Venice Lagoon on 6 September 1981.

Blue crabs have been recorded from the brackish lagoons on the Adriatic coast of Apulia: from Varano lagoon in the summer of 2007 and from Lesina lagoon between June and October 2007 (Florio et al. 2008). A specimen was collected also near Lecce on the Salento peninsula where it was caught by fishermen in January 2001. Subsequent records attest to the gradual increase of population and it’s attraction to many stakeholders (Gennaio et al. 2006). It seems that C. sapidus endures in these large brackish basins in southern Italy.

Ghisotti (1966) and Torchio (1967) had published records of C. sapidus from Sicily, however, the specimens were sent for verification and identified as N. pelagicus (Holthuis 1969). Shortly thereafter, in spring 1970, a female C. sapidus was found near the harbour of Messina, and another female was fished nearby in autumn 1972 (Cavaliere and Berdar 1975). Trawling surveys off the eastern coast of Sicily between 1988 and 1990 collected C. sapidus though details are missing (Franceschini et al. 1993). Pipitone and Arculeo (2003) doubt the establishment of the species in Sicilian waters.

Only three specimens are known from the Ligurian Sea: two specimens from the port of Genoa and the surrounding waters collected in 1962, and a large male caught in a fish trap near La Spezia, in the Gulf of Genoa in 1965 (Tortonese 1965).

Lebanon The first record collected from St. George Bay, Beirut, in 1965 and consisted of 1 male and 12 females, 3 ovigerous (George and Athanassiou 1965). The authors judged the crab quite abundant as it featured prominently in the local fish markets and roadside stands. Local fishermen claimed the species had been in Lebanon for at least the previous 5 years (George and Athanassiou 1965). This information corresponds with an unverified observation by the authors that a throw net fisherman caught blue crabs on 17 February 1964 in the Kebir estuary, in northern Lebanon. Shiber (1981) examined a specimen which was collected off Antelias, near Beirut, on 15 April 1965. Serbetis (1959) reported blue crabs from the markets of Beirut, but Holthuis (pers. comm. in Shiber 1981) suggested that the colour of his specimens indicates they may have been N. pelagicus. The frequent records in the 1960s have allowed an established population in the coastal waters of Lebanon (George and Athanassiou 1965). Though no recent records are known, it may still exists there, as it does off the Israeli coast.

Malta Two male specimens were trapped in Marsaxlokk Bay on 20 November 1972 (Schembri and Lanfranco 1984). No other Maltese specimens have been found (P.J. Schembri pers. comm.).

Syria Saker and Farah (1994, cited by CIESM 2008) report the species off Lattakia, though no details were given and no information about the status of the population of this species is available. Today blue crabs are sold in Syrian markets, however, their origin is unknown (P.Y. Noël pers. comm.). Possibly the population is connected with the established populations along the Lebanese and Turkish coasts.

Turkey Artüz (1990) affirmed C. sapidus was introduced intentionally between 1935 and 1945 into the northern Aegean Sea, particularly into the Gulf of Saros (Turkey) and in the Gulf of Thessaloniki (Greece). It initially did well but was later displaced to the southern Aegean and gradually came to occupy the Turkish Mediterranean coast. Serbetis (1959) mentioned that the crabs were caught in a lagoon on the Turkish coast off Samos in 1947. However, the narrative of intentional introduction has not verified. The first specimens of C. sapidus firmly recorded from Turkey were four males and two females collected in brackish Lake Akyatan near the border with Syria in May 1959 (Holthuis 1961).

The distribution and abundance of records between 1985 and 1995 show that it was well established in at least 15 lagoons, estuaries and bays on the Levantine and Aegean coasts (Enzenroß et al. 1997). In most locations the crabs were fished commercially. In the early 2000s about 200 tons were sold annually, but since 2003 its catches diminished substantially to only 17 tons in 2008 (Anonymous 2009). Overfishing, pollution, epidemic or combinations thereof are blamed: the “black spot disease” was observed in spring 1995 at some locations (Enzenroß et al. 1997).

References to the presence of the species in the Sea of Marmara remain as yet unconfirmed (e.g., Zaitsev and Öztürk 2001; Tuncer and Bilgin 2008). Müller (1986), referring to Georgiadis and Georgiadis (1974), assumed that the crabs offered for sale in the fish markets of Istanbul had been fished in the Marmara Sea. However, they were in all likelihood fished in the Aegean Sea or imported from Greece. Though recently, in November 2008, an adult female was collected with gillnet off Canakkale, the Dardanelles (Tuncer and Bilgin 2008).

2.5 Black Sea

Bulgaria The first record in the Black Sea was an adult female caught in October 1967 in the western part of Varna Bay, near Asparuchowo (Bulgurkov 1968). In 1984, a second specimen was found (Zaitsev and Öztürk 2001). The most recent record dates to August 2006. A single specimen was caught by a fisherman in his net while fishing off Burgas (Anonymous 2006). The intermittent records may signify the species has not yet established a population.

Romania On 23 August 1998 an adult male was collected off Mangalia, near the border with Bulgaria and an adult female caught in a tuna trap on 8 October 1999 nearby (Petrescu et al. 2000). Another female was captured off Agigea in 2000 (Micu and Micu 2006). The authors conclude that there is no self-maintaining population along the Romanian coast of the Black Sea.

Turkey Özturk (pers. comm. in Zaitsev and Mamaev 1997) recorded the species from the Bosphorus. But a more recent check-list of the crustacean fauna of the Bosphorus fails to list it (Balkis et al. 2002).

Ukraine The first record is based on a male specimen caught in the Kerch Strait near Bolshoi Utrish Cape in June 1975 (Monin 1984). In 1980s C. sapidus was recorded at the Crimean coast (Revkov 2003). It has been recently reported increasingly abundant nearshore off Sevastopol (Shiganova 2008), but the report could not be verified. It remains unclear whether the species had established a population in the area.

2.6 Sea of Azov

Russia Callinectes sapidus was recorded in the Sea of Azov in 1967 (DAISIE 2009), though the record remained unverified.

3 Pathways of Introduction

Although C. sapidus has been repeatedly collected over the past century in many locations in European seas, it is unknown how the species had arrived in Europe. It is proposed that multiple independent introductions had taken place, possibly utilizing different pathways, even to the same sites.

Already Bouvier (1901), who published the first occurrence of the species in Europe, has speculated on the manner of its arrival. The specimen could have arrived in the harbour of Rochefort through shipping, in a ship’s boat or in a corner full of water, or in vessels’ fouling community. However, it is unlikely the crab with its affinity to brackish water would cross oceans on ships’ hulls or as suggested by Wolff (1954) with floating seaweeds. The later pathway would also fail to explain the presence of the crabs in remote areas such as the northern Adriatic, eastern Mediterranean or Black Sea. Transport in ballast tanks is considered the most likely vector because, in its native range, C. sapidus is abundant next to major shipping routes and had been found in its introduced range initially in or nearby ports, where ballast water are discharged (cf. Wolff 1954; Holthuis and Gottlieb 1955). Direct evidence was supplied recently, when three living specimens had been found in ballast tanks but none on ships’ hulls (Gollasch 1996). During ballast intake, juveniles, or more likely, planktonic larvae, maybe by swept in with the water (Holthuis and Gottlieb 1955; Mizzan 1993). As the larval development of C. sapidus lasts from about 37–69 days (Hill et al. 1989), long enough to make vessel transport plausible. In other cases, different transport mechanisms could be involved. The species, commercially valuable (from sapidus (Latin) = “savory”), may have been introduced intentionally or has been accidentally released from holding tanks in which live crabs had been imported for human consumption or for the aquarium trade (ICES WGITMO 2006). Records of intact but boiled specimens on the Dutch North Sea coast (Wolff 2005), seem to indicate that C. sapidus is consumed aboard vessels, and it is possible that leftovers (boiled or live specimens) were thrown overboard (cf. Nehring et al. 2008).

Callinectes sapidus is most valuable in commercial fisheries, providing a highly acceptable, nutritious product worth several million dollars annually in the USA alone. Consequently the intentional release of blue crabs into Europe to support a fishery should not be excluded as suggested by Artüz (1990) it for the northern Aegean Sea. However, our knowledge about worldwide transfers of blue crabs (and other alien species) inclusive evidences for their ultimately fates is extremely limited so far. An improvement of providing of specific data is indispensable for a forward-looking alien management.

Beyond the initial human-mediated introduction, the rapid and widespread dispersal from the areas of introduction may also be an important factor in arriving new habitats in broader environs. Among larval transport by water currents, occasional records of adult blue crabs in new areas may likely be explained in some cases by long-distance migrations of blue crabs from areas of their established populations – like in case of records of adult specimens of the Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis in the Baltic (Ojaveer et al. 2007). Hill et al. (1989) underline that adult blue crabs are excellent swimmers and can migrate long distances over the sea bottom (Stimpson erected the Genus Callinectes in 1860 and derived it from calos (Greek) = strenuus (Latin) = “strenuous” and nectes (Greek) = natator (Latin) = “swimmer”). Especially female blue crabs can move several hundred kilometers (Hill et al. 1989), wherein just fertilized or ovigerous females have an enhanced potential for bio-contamination of new habitats. A passive dispersal of juvenile or adult specimens of C. sapidus as hitchhikers on ships’ hulls is also possible, but probably for relatively short distances only.

In general, the invasion history of C. sapidus in European and adjacent waters is unknown in detail up to now. However, identification of source populations and reconstruction of possible pathways of invasion are key issues in our understanding of the invasion process and especially in the design of effective measures to minimise introduction and spreading of alien species. Molecular markers provide effective tools to investigate invasion histories, as actually shown for the occurrence of E. sinensis in European and North American waters (Hänfling et al. 2002). Conducting genetic analyses based on older voucher as well as on living specimens from different native and non native occurrences would be an important step for understanding the invasion history of C. sapidus in its introduced range.

4 Factors for Establishment

Brackish waters are characterized by the lowest number of indigenous species (“Artenminimum” sensu Remane 1934) and seem to have many open ecological niches (Nehring 2006). But brackish waters are often exposed to intensive international ship traffic, one of the most important vectors for aquatic alien species. Thus, these habitats have the highest potential for species introductions (Nehring 2006). Callinectes sapidus is a typical brackish water species, necessitates the presence of estuaries or lagoons which are necessary environments for the completion of its life-cycle. It tolerates salinities ranging from freshwater to hypersaline, but growth of megalopae and small juvenile crabs may be normal at salinities of 5 psu (Hill et al. 1989). Blue crabs are more tolerant of low temperatures than are many other species of fishes and shrimp, however, according to laboratory experiments development of blue crab larvae requires water temperatures of more than 21°C (Hill et al. 1989). So it’s no wonder that since 1900 C. sapidus could establish populations in several utilizable European and adjacent waters, in some cases supported by waters artificially warmed by power plants (Table 1). But not every introduction was successfully in the long run. Among insufficient habitats and environmental pollution, too low water temperatures seem an important factor for the non establishment of C. sapidus especially in northern Europe and in the Black Sea. However, indications suggest that water temperatures will become warmer due to continuing climate change (e.g., Mackenzie and Schiedek 2007). In consequence, the temperature regime will probably become more favourable for blue crabs in not yet occupied areas in the near future.

5 Ecological and Economic Impacts

Together with r-selected life history traits (high fecundity and dispersal capacity, fast growth), the broad environmental tolerances predispose C. sapidus as a likely successful invader (Hill et al. 1989). Blue crabs perform a variety of ecosystem functions and can play a major role in energy transfer within estuaries and lagoons. At various stages in the life cycle, blue crabs serve as both prey and as consumers of plankton, small invertebrates, fish, and other crabs. They are important detritivores and scavengers and, if food is in short supply, even also cannibals (Hill et al. 1989). They are aggressive towards other species, and compete with other crabs for food and space (Gennaio et al. 2006; Nehring et al. 2008). Callinectes sapidus is also a host to several parasites and diseases, some with a high potential to cause mass mortalities (Messick and Sindermann 1992). Thus the introduction of blue crabs can have significant consequences to the ecology of the invaded environments. Despite the nomination of C. sapidus as one of the 100 ‘Worst Invasive Alien species in the Mediterranean’ (Streftaris and Zenetos 2006), up to now the definite long term impacts of C. sapidus to non-native environments are unknown although since decades this alien species has established distinct permanent populations especially in the eastern Mediterranean Sea where particularly high abundances of blue crabs could be observed. Intensified research in this field should be undertaken.

Callinectes sapidus supports an important fishery in its native range along the Atlantic coast of North-America as well as in its introduced range in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. However, due to climate change and its supposed positive effects on the occurrence of blue crabs, C. sapidus might well become a candidate for a target species in commercial fishery elsewhere. This could be a real scenario for example in the Adriatic Sea, at the European Atlantic coast and in the North Sea. Otherwise in this context it will be an interesting question whether C. sapidus will significantly reduce stocks of the introduced Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas), which is commercially used in several European countries because adult blue crabs prefer molluscs such as oysters as their primary food sources (Hill et al. 1989). Blue crabs are reported to mutilate fish caught in traps and trammel nets, and tear those nets (Banoub 1963; Beqiraj & Kashta 2010). The occurrence of C. sapidus could be also an important harmful factor in the human health system as well as in the tourism sector because blue crabs have been implicated as carriers of strains of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae which are responsible for outbreaks of human cholera (Hill et al. 1989). However, comprehensive analyses about the economic benefits and disadvantages of C. sapidus in its introduced range are not done so far. This should be put into action now.

References

Abdel-Razec FA (1987) Crab fishery of the Egyptian waters with notes on the bionomics of Portunus pelagicus (L.). Acta Adriat 28:143–154

Adema JPHM (1983) Nogmaals de blauwe zwemkrab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896. Zeepaard 43:14

Adema JPHM (1991) De krabben van Nederland en België (Crustacea, Decapoda, Brachyura). Nationaal Natuurhistorisch Museum, Leiden

Amanieu M, Le Dantec J (1961) Sur la présence accidentelle de Callinectes sapidus M. Rathbun à l’embouchure de la Gironde. Rev Trav Inst Pêches Marit 25:339–343

Anonymous (2003) De Blauwe zwemkrab is nu ook in de Oosterschelde aangetroffen. http://www.anemoon.org/anemoon/spuisluis/2003/021105.htm. Cited 13 Sep 2009

Anonymous (2006) Amerikanische Blaukrabbe illegal ins Schwarze Meer eingewandert. http://www.bnr.bg/radiobulgaria/emission_german/theme_foto_des_tages/material/fdt060825.htm. Cited 15 Feb 2009

Anonymous (2009) Quantity of caught other sea fish (crustaceas, molluscs). www.tuik.gov.tr/PreIstatistikTablo.do?istab_id=694. Cited 6 Sep 2009

Artüz I (1990) Mavi yengecin serüvenleri. Cumhuriyet Bilim Teknik 148:6

Balkis N, Albayrak S, Balis H (2002) Check-list of the Crustacea fauna of the Bosphorus. Turk J Mar Sci 8:157–164

Banoub MW (1963) Survey of the Blue-Crab Callinectes sapidus (Rath.), in Lake Edku in 1960. Alexandria Institute of Hydrobiology, Notes and Memoirs 69:1–20

Beqiraj S, Kashta L (2010) The establishment of blue crab Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 in the Lagoon of Patok, Albania (south-east Adriatic Sea). Aquat Invas 5:219–221

Boschma H (1972) On the occurrence of Carcinus maenas (Linnaeus) and its parasite Sacculina carcini Thompson in Burma, with notes on the transport of crabs to new localities. Zool Meded 47:145–155

Bouvier EL (1901) Sur un Callinectes sapidus M. Rathbun trouvé à Rochefort. Bull Mus Hist Nat Paris 7:16–17

Bulgurkov K (1968) Callinectes sapidus Rathbun (Crustacea - Decapoda) v Cherno more. Izv Nauchnoizsled Inst Okeanogr Ribno Stop Varna 9:97–99

Cabal J, Millán JAP, Arronte JC (2006) A new record of Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) from the Cantabrian Sea, Bay of Biscay, Spain. Aquat Invas 1:186–187

Cavaliere A, Berdar A (1975) Presenza di Callinectes sapidus Rathbun (Decapoda Brachyura) nello Stretto di Messina. Boll Pesca Piscic Idrobiol 30:315–322

CIESM (2008) Callinectes sapidus. http://www.ciesm.org/atlas/Callinectessapidus.php. Cited 6 Sep 2009

Clark PF (1984) Recent records of alien crabs in Britain. Naturalist 109:111–112

Craeymeersch JA, Kamermans P (1996) Waarnemingen van de blauwe zwemkrab Callinectes sapidus in de Oosterschelde. Zeepaard 56:21–22

DAISIE (2009) Species Factsheet, Callinectes sapidus. http://www.europe-aliens.org. Cited 2 Oct 2009

Demetropoulos A, Neocleous D (1969) The fishes and crustaceans of Cyprus. Fisher Dept Cyprus, Fisher Bull 1:1–21

Den Hartog C, Holthuis LB (1951) De Noord-americaanse “Blue Crab” in Nederland. Levende Nat 54:121–125

Enzenroß R, Enzenroß L, Bingel F (1997) Occurrence of blue crab, Callinectes sapidus (Rathbun 1896) (Crustacea, Brachyura) on the Turkish Mediterranean and the adjacent coast and its size distribution in the Bay of Üskenderun. Turk J Zoo 21:113–122

Florio M, Breber P, Scirocco T, Specchiulli A, Cilenti L, Lumare L (2008) Exotic species in Lesina and Varano lakes: Gargano National Park (Italy). Transit Waters Bull 2:69–79

Food and Agriculture Organization (2007) Species Fact Sheet Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896. http://www.fao.org/fishery/species/2632/en. Cited 27 Sep 2009

Franceschini G, Andaloro F, Diviacco G (1993) La macrofauna dei fondi strascicabili della Sicilia Orientale. Natu Sicil 17:311–324

Galil B (1993) The composition and diversity of planktonic larval decapoda off the Mediterranean coast of Israel. MAP Technical Reports Series 73, UNEP, Athens

Gaudencio MJ, Guerra MT (1979) Note sur la présence de Callinectes sapidus Ratbun 1896 (Crustacea Decapoda Brachyura) dans l’estuaire du Taje. Bol Inst Nac Invest Pescas 2:67–73

Geiter O (2000) Blaukrabbe in der Weser gefangen. Neozoen Newsl 3:9

Gennaio R, Scordella G, Pastore M (2006) Occurrence of blue crab Callinectes sapidus (Rathbun, 1986 Crustacea, Brachyura), in the Ugento ponds area (Lecce, Italy). Thalassia Salentina 29:29–39

George CJ, Athanassiou V (1965) The occurrence of the American blue crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, in the coastal waters of Libanon. Doriana 4:1–3

Georgiadis C, Georgiadis G (1974) Zur Kenntnis der Crustacea Decapoda des Golfes von Thessaaloniki. Crustaceana 26:239–248

Ghisotti F (1966) Il Callinectes sapidus Rathbun nel Mediterraneo (Crustacea, Decapoda). Natura 57:177–180

Giordani Soika A (1951) Il Neptunus pelagicus (L.) nell’Alto Adriatico. Natura 42:18–20

Gollasch S (1996) Untersuchungen des Arteintrages durch den internationalen Schiffsverkehr unter besonderer Berücksichtigung nichtheimischer Arten. Verlag Dr. Kovac, Hamburg

Gollasch S, Nehring S (2006) National checklist for aquatic alien species in Germany. Aquat Invas 1:245–269

Hänfling B, Carvalho GR, Brandl R (2002) mt-DNA sequences and possible invasion pathways of the Chinese mitten crab. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 238:307–310

Hill J, Fowler DL, Avyle MV (1989) Species profiles: Life histories and environmental requirements of coastal fishes and invertebrates (Mid-Atlantic) - Blue crab. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Vicksburg

Holthuis LB (1961) Report on a collection of Crustacea Decapoda and Stomatopoda from Turkey and the Balkans. Zool Verh Leiden 47:1–67

Holthuis LB (1969) Enkele interessante Nederlandse Crustacea. Bijdragen tot de faunistiek van Nederland. I. Zool Bijdr Leiden 11:34–48, pl. 1

Holthuis LB, Gottlieb E (1955) The occurence of the american Blue Crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, in Israel waters. Bull Res Counc Israel 5B:154–156

ICES WGITMO (2000) Report of the Working group on Introductions and Transfers of marine Organisms, Parnu, Estonia, 27–29 March 2000. ICES CM 2000/ACME:07

ICES WGITMO (2001) Report of the Working group on Introductions and Transfers of marine Organisms, Barcelona, Spain, 21–23 March 2001. ICES CM 2001/ACME:08

ICES WGITMO (2003) Report of the Working group on Introductions and Transfers of marine Organisms, Vancouver, Canada, 26–28 March 2003. ICES CM 2003/ACME:04

ICES WGITMO (2004) Report of the Working group on Introductions and Transfers of marine Organisms, Cesenatico, Italy, 25–26 March 2004. ICES CM 2004/ACME:05

ICES WGITMO (2006) Report of the Working group on Introductions and Transfers of marine Organisms, Oostende, Belgium, 16–17 March 2006. ICES CM 2006/ACME:05

ICES WGITMO (2007) Report of the Working group on Introductions and Transfers of marine Organisms, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 21–23 March 2007. ICES CM 2007/ACME:05

Ingle RW (1980) British crabs. British Museum (Natural History), London

Kerckhof F, Haelters J (2005) Enkele opmerkelijke waarnemingen en strandingen in 2004 en 2005. De Strandvlo 25:101–105

Kerckhof F, Haelters J, Gollasch S (2007) Alien species in the marine and brackish ecosystem: the situation in Belgian waters. Aquat Invas 2:243–257

Kevrekidis K, Galil BS (2003) Decapoda and Stomatopoda (Crustacea) of Rodos island (Greece) and the Erythrean expansion NW of the Levantine Sea. Medit Mar Sci 4:57–66

Kinzelbach R (1965) Die Blaue Schwimmkrabbe (Callinectes sapidus), ein Neubürger im Mittelmeer. Nat Mus 95:293–296

Kühl H (1965) Fang einer Blaukrabbe, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun (Crustacea, Portunidae) in der Elbmündung. Arch Fisch Wiss 15:225–227

Lai JCY, Ng PKL, Davie PJF (2010) A revision of the Portunus pelagicus (Linnaeus, 1758) species complex (Crustacea: Brachyura: Portunidae) with the recognition of four species. Raffles Bull Zool 58:199–237

Lewinsohn C, Holthuis LB (1986) The crustacea decapoda of Cyprus. Zool Verh Leiden 230:1–64

Mackenzie BR, Schiedek D (2007) Daily ocean monitoring since the 1860s shows record warming of northern European seas. Glob Chang Biol 13:1335–1347

Maes J, Taillieu A, van Damme PA, Cottenie K, Ollevier F (1998) Seasonal patterns in the fish and crustacean community of a turbid temperate estuary (Zeeschelde Estuary, Belgium). Estuar cst Shelf Sci 47:143–152

Messick GA, Sindermann CJ (1992) Synopsis of principal diseases of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus. NOAA Technical Memorandum, Woods Hole

Micu S, Micu D (2006) Proposed IUCN regional status of all Crustacea: Decapoda from the Romanian Black Sea. Ann Sci Univ “AlICuza” Iasi, sect Biol Animala 52:7–38

Mizzan L (1993) Presence of swimming crabs of the genus Callinectes (Stimpson) (Decapoda, Portunidae) in the Venice Lagoon (North Adriatic Sea - Italy): first record of Callinectes danae Smith in European waters. Boll Mus civ Stor nat Venezia 42:31–43

Mizzan L (1999) Le specie alloctone del macrozoobenthos della laguna di Venezia: il punto della situazione. Boll Mus Civ Stor Nat Venezia 49:145–177

Monin VL (1984) A new finding of Callinectes sapidus (Decapoda, Brachyura) in the Black Sea. Zool Zhurnal 63:1100–1102

Müller GJ (1986) Review of the hitherto recorded species of Crustacea Decapoda from the Bosporus, the Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles. Cercetari Mar 19:109–130

Nehring S (2006) Four arguments why so many alien species settle into estuaries, with special reference to the German river Elbe. Helgol Mar Res 60:127–134

Nehring S, van der Meer U (2010) First record of a fertilized female blue crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura), from the German Wadden Sea and subsequent secondary prevention measures. Aquat Invas 5:215–218

Nehring S, Speckels G, Albersmeyer J (2008) The American blue crab Callinectes sapidus Rathbun on the German North Sea coast: Status quo and further perspectives. Senckenbergiana Marit 38:39–44

Ojaveer H, Gollasch S, Jaanus A, Kotta J, Laine AO, Minde A, Normant M, Panov VE (2007) The Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis in the Baltic Sea – a supply-side invader? Biol Invas 9:409–418

Onofri V, Dulčić J, Conides A, Matić-Skoko S, Glamuzina B (2008) The occurrence of the blue crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Decapoda, Brachyura, Portunidae) in the eastern Adriatic (Croatian coast). Crustaceana 81:403–409

Pancucci-Papadopoulou MA, Zenetos A, Corsini-Foka M, Politou ChA (2005) Update of marine alien species in Hellenic waters. Medit Mar Sci 6:147–158

Petrescu I, Papadopol N, Nicolaev S (2000) O nouă specie pentru fauna de decapode din apele marine româneşti, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun 1896. Anal Dobrogei 6:222–228

Pipitone C, Arculeo M (2003) The marine Crustacea Decapoda of Sicily (central Mediterranean Sea): a checklist with remarks on their distribution. Ital J Zool 70:69–78

Ramadan SE, Dowidar NM (1972) Brachyura (Decapoda, Crustacea) from the Mediterranean waters of Egypt. Thalassia Jugosl 8:127–139

Rappé G (1985) Vestigt de blauwe zwemkrab, Callinectes sapidus zich blijvend in de Zuidelijke Noordzee? De Strandvlo 5:8–11

Rathbun MJ (1930) The cancroid crabs of America of the families Euryalidae, Portunidae, Atelecyclidae, Cancridae and Xanthidae. US Nat Mus Bull 152:1–609

Remane A (1934) Die Brackwasserfauna. Verh dt zool Ges 36:34–74

Revkov NK (2003) Taxonomical composition of the bottom fauna at the Black Sea Crimean coast. In: Eremeev VN, Gaevskaya AV (eds) Modern condition of the biodiversity of the coastal zone of Crimea (Black Sea region). Ekosi-Gidrophizika, Sevastopol

Schembri PJ, Lanfranco E (1984) Marine Brachyura (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) from the Maltese Islands and surrounding waters (Central Mediterranean). Centro 1:21–39

Serbetis C (1959) Un nouveau crustacé commestible en mer Egeé Callinectes sapidus Rath. (Decapode brach.). Proc Gen Fish Counc Medit 5:505–507

Shiber JG (1981) Brachyurans from Lebanese waters. Bull Mar Sci 31:864–875

Shiganova T (2008) Introduced species. Hdb Env Chem 5Q:375–406

Snovsky Z, Galil BS (1990) The occurrence of the American blue crab, Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, in the Sea of Galilee. Bamidgeh 42:62–63

Stimpson W (1860) Notes on North American Crustacea, No. 2. Ann Lyceum Nat Hist 7:176–246

Streftaris N, Zenetos A (2006) Alien marine species in the Mediterranean - the 100 ‘Worst Invasives’ and their impact. Medit Mar Sci 7:87–118

Tendal OS, Flintegaard H (2007) Et fund af en sjælden krabbe i danske farvande: den blå svømmekrabbe, Callinectes sapidus. Flora Fauna Århus 113:53–56

Torchio M (1967) Il Callinectes sapidus Rathbun nelle acque siciliane (Crustacea, Decapoda). Natura 58:81

Tortonese E (1965) La comparsa di Callinectes sapidus Rath. (Decapoda Brachyura) nel Mar Ligure. Doriana 4:1–3

Tuncer S, Bilgin S (2008) First record of Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) in the Dardanelles, Canakkale, Turkey. Aquat Invasions 3:469

Van Damme P, Maes J (1993) De Blauwe Zwemkrab Callinectes sapidus Rathbun, 1896 in de Westerschelde (Belgium). De Strandvlo 13:120–121

Vincent T (1986) Les captures de Callinectes sapidus (Rathbun, 1896) en baie de Seine, entre 1975 et 1984. Bull trim Soc Géol Normandie et Amis du Muséum du Havre 73:13–15

Vincent T (1999) Callinectes sapidus (Decapoda, Brachyura, Portunidae). Essai de synthese sur 23 ans d’observations en baie de Seine. Bull trim Soc géol Normandie Amis Mus Havre 86:13–17

White M, Haxhiu I, Saçdanaku E, Petri L, Rumano M, Osmani F, Vrenozi B, Robinson P, Kouris S, Boura L, Venizelos L (2009) Monitoring and conservation of important sea turtle feeding grounds in the Patok Area of Albania, 2008 Annual Report. The Mediterranean Association to Save the Sea Turtles, Athens.

Williams AB (1974) The swimming crabs of the Genus Callinectes (Decapoda, Portunidae). Fish Bull 72:685–798

Williams AB (1984) Shrimps, lobsters, and crabs of the Atlantic coast of the Eastern United States, Maine to Florida. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington

Wolff T (1954) Tre ostamerikanske krabber fundet i Danmark. Flora Fauna Århus 60:19–34

Wolff WJ (2005) Non-indigenous marine and estuarine species in The Netherlands. Zool Med 79-1:1–116

WWF/Adena (2002) Doñana y el cambio climático. WWF/Adena, Madrid

Zaitsev Y, Mamaev V (1997) Biological diversity in the Black Sea: a study of change and decline. United Nations Publications, New York

Zaitsev Y, Öztürk B (2001) Exotic species in the Aegean, Marmara, Black, Azov and Caspian Seas. Turkish Marine Research Foundation, Istanbul

Acknowledgements

I am grateful, for information, and help with the bibliography to: U. Albrecht, A.S. Ates, E. Bozhikowa, P.F. Clark, J.A. Craeymeersch, C. Frogila, B. Galil, V. Golemansky, F. Kerckhof, J.C.Y. Lai, P.Y. Noël, V. Onofri, I. Petrescu, P.J. Schembri, T. Shiganova, H. Simon, and H. Zibrowius. I also thank Paul F. Clark, Cedric d’Udekem d’Acoz and Bella Galil for their suggestions to improve the manuscript and for language revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2011 Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Nehring, S. (2011). Invasion History and Success of the American Blue Crab Callinectes sapidus in European and Adjacent Waters. In: Galil, B., Clark, P., Carlton, J. (eds) In the Wrong Place - Alien Marine Crustaceans: Distribution, Biology and Impacts. Invading Nature - Springer Series in Invasion Ecology, vol 6. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0591-3_21

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-0591-3_21

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Dordrecht

Print ISBN: 978-94-007-0590-6

Online ISBN: 978-94-007-0591-3

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)