Abstract

The doubling time of indigenous bacteria in mixing-zone of hydrothermal fluid and seawater was determined using a diffusion chamber unit deployed on the field of Hatoma Knoll (24° 51.50′N, 123° 50.50′ E), which is a submarine volcano located on southern Okinawa Trough. The diffusion chamber is a reliable tool to incubate and to directly measure the microbial growth under in situ condition of deep-sea, although an operation of submersible and a complicated preparation of seed water became the technical constraints. The doubling time at non-vent site distant from active vent site was estimated from 86 to 110 h, while at active vent sites more rapid doubling time, 21–32 h, were estimated. A potential sulfur-oxidizing bacteria belonging to Epsilonproteobacteria dominated the population grew in the chambers, which were incubated using the plume water obtained from the mixing zone between the vent fluid and seawater, and Bathymodiolus colony, while no detection of Gammaproteobacteria. The methane-oxidizing bacteria were detected only from gill and digestive tract of Bathymodiolus platifrons, and could not be detected from the chamber, although the chamber was placed on Bathymodiolus colony. The results of this study suggested that chemolithoautotrophic growth near by the hydrothermal vent is sustained by the rapid doubling time of Epsilonproteobacteria using chemical species dissolved in fluid and provides the chemoautotrophic product to deep-sea benthopelagic community, as well as a microbial products in hydrothermal vent plume.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The discovery of high-density animal aggregations in the vicinity of hydrothermal vents of the Galapagos Rift (Corliss et al. 1979; Lonsdale 1977) raised many questions for the mechanism to sustain the ecosystem, especially for the source of primary production. Chemosynthesis of prokaryotes, depending on the inorganic chemical reaction between hydrothermal fluid and seawater, has been recognized major energy source of primary production in the hydrothermal ecosystems (Jannasch and Mottl 1985; Karl et al. 1980). Growth rate of microbial community in hydrothermal system is most useful data to qualify a primary production by chemosynthesis.

Potential chemical energy for the chemolithoautotrophic growth has been calculated by chemical thermodynamics based on geochemical data of hydrothermal fluids (Amend and Shock 1998; Jannasch and Mottl 1985; McCollom 2000; McCollom and Shock 1997; Schmidt et al. 2008). The primary production based on chemical energy sustains the huge biomass in megafauna and their rapid growth rate, for examples, 85 cm/year determined by tube length of Riftia pachyptila (Lutz et al. 1994), 10 cm/year growth and long lived of Lamellibrachia sp. (Bergquist et al. 2000), a biomass of the mussel bed exceeded 70 kg/m2 of weight at Logatchev area (Gebruk et al. 2000). The biomass of endosymbiotic bacteria in such invertebrates determined by quinone biomarker suggested sustainable power of chemosynthetic primary production (Yamamoto et al. 2002), despite no data of microbial growth rate directly measured from the symbionts.

Investigation of in situ growth of free-living microbial community in ocean habitats is difficult yet due to the non-culturable or slow growing physiology in majority of marine prokaryotes. Several parameters without traditional cultivation methods have been used to estimate microbial growth rate, e.g. microscopic cell density and cell size, adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP), assimilation rate of isotope labeled substrates (Karl et al. 1980; Kirchman 2001; Malmstrom et al. 2005; Torrton and Dufour 1996), microbial mat formation based on time-series observation (Taylor et al. 1999), frequency of dividing cells (Newell and Christian 1981), macromolecular synthesis (Torrton and Dufour 1996), whole-genome microarray analysis (Holmes et al. 2013). These methods were applied in the hydrothermal environments (Jannasch and Mottl 1985; Karl et al. 1980) as well as general oceanic environments, and the calibration methods to convert growth rate or doubling time from these parameters have been developed (Kirchman 2001; Sherr et al. 1999; Torrton and Dufour 1996; Yokokawa et al. 2004).

Another technical issue to determine microbial growth rate in deep-sea hydrothermal vent is an incubation method under in situ physical and chemical conditions. The so-called pressure simulated in situ incubation system equipped in laboratory was used to determine the indigenous heterotrophic marine bacteria isolated from 75 to 5,550 m depth (Carlucci and Williams 1978; Williams and Carlucci 1976). The in situ chamber approach is a convenient method to incubate the indigenous microbes under original habitat condition. It has been applied in deep-sea expeditions for hydrothermal vents, and successfully isolated and/or accumulated novel chemolithotrophic bacteria (Higashi et al. 2004; Reysenbach et al. 2000; Takai et al. 2003). Of theses several types of in situ chambers, a diffusion chamber is a very useful apparatus for in situ physiological experiments of microbes (Bollmann et al. 2007; McFeters and Stuart 1972; Vasconcelos and Swartz 1976), in situ determination of growth rate of phytoplankton (Furnas 1991) and thermophiles in alkaline geothermal pool (Kimura et al. 2010).

In this study, in situ experiments using a diffusion chamber unit were carried out on Hatoma Knoll in southern Okinawa Trough to estimate the state of microbial growth in mixing-zone of hydrothermal vent area on the knoll.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Sample Collection

The in situ incubation experiments were conducted during three cruises, NT01-05, NT02-07, and NT04-03 at hydrothermal and methane seep areas on the southern Ryukyu Archipelago. In these cruise, water samples were collected and prepared for the in situ experiments using diffusion chamber, and deployed the chambers in the following sites; a vent field of the Hatoma Knoll (24° 51.500′ N, 123° 50.500′ E) and a methane seep field of the Kuroshima Knoll (24° 8.000′ N, 124° 11.500′ E). Hatoma Knoll is a submarine volcano located in the southern Okinawa Trough of the southwestern Ryukyu arc. Hydrothermal activity of the Hatoma Knoll has been discovered at a rim and a center mound of horse-shoe shaped caldera on the knoll at 1,490–1,530 m in the deep-sea expedition of 1999 and 2000 (Watanabe 2001). Prominent hydrothermal activity occurs over a central mound and created two big-chimneys with discharge of high temperature fluid up to max. 300 °C (Table 33.1, Suppl. 33.1). These two big-chimneys collapsed in July of 2006. Kuroshima Knoll is a methane seep field located in the south of Ishigaki-island and isolated from island shelf. It was used as reference site for in situ growth chamber experiments in NT04-03 cruise. The gas bubbles were rising from the Bathymodiolus colony of deep-sea mussels at seafloor of 600–700 m in water-depth.

The water samples were collected either by a Niskin bottle sampler, ORI manifold sampler or syringe type water sampler using the human occupied vehicle (HOV) Shinkai 2000, or remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Hyper-Dolphin 3000. The sample of deep-sea mussel, Bathymodiolus platifrons, was collected in NT03-09 to analyze the microbial flora of gill and digestive tract. The video footages recorded whole operations on the experiment sites of NT01-05 and NT02-07 were accessible at the JAMSTEC E-library of Deep-sea Images (http://www.godac.jamstec.go.jp/jedi). The identification codes for video clips are “2K1270SHDB4028”, and “2K1353SHDB6021” for Shinkai 2000 dives, respectively. The video clips of ROV dives of 2003 and 2004 are yet preparing in 2013.

2.2 Preparation and In Situ Experiment Using a Diffusion Chamber

The diffusion-chamber based approach was applied for determination of microbial growth under in situ condition of deep-sea hydrothermal vent field. The chamber was designed to make a cultivation space (ca. 35 mL) sealed with polycarbonate membrane filter (0.2 μm-pore-size), which permit to exchange chemicals and organic matters between inside and outside of the chamber (Fig. 33.1). The chamber was filled with 0.2 μm filter-sterilized seawater, which was collected from the experimental site. No artificial supplement was added in the chamber. Both of the prepared chamber and the seeds-water were preserved in 4 °C until the time to next dive for chamber experiment. Just before a dive the chambers were inoculated with the seed-water (Fig. 33.1), the chambers set in the canister were settled in the payload container filled with cold seawater, transported by the deep-sea submersibles, and placed on the experiment sites. For this experiment, three kinds of seeds-water specimens were collected respectively from the mixing zone of 1 m heights on vent, within the Bathymodiolus colony, and the surface seawater as negative reference. In the growth experiment, a seed-water filtered by 1 μm pore size membrane filter was prepared to examine an effect of protista predation on microbial growth rate. In the cruise of NT04-03, compact thermometer (MDS-MkV/T, JFE Advantech Co., Ltd.) was attached on the canister for determination of temperature fluctuation during in situ incubation experiments (Suppl. 33.2).

In situ experiment conducted in NT04-03 cruise at hydothermal vent of Hatoma Knoll. (a) Chamber on hydrothermal vent (site 1), (b) canisters contained chambers in aggregation of Shinkaia crosnieri (site 2), (c) canisters contained chambers settled in Bathymodiolus colony (site 3), (d) location of hydrothermal vents and experiments sites on the moud, (e, f) profile of chamber with membrane filter, and (g) punched canisters contained chambers

2.3 Microbial Population and Growth

The cells fixed with 1 % paraformaldehyde were collected on polycarbonate membrane (0.2 μm-pore-size), and stained with acridine orange or DAPI (Hobbie et al. 1977). The microbial cells were observed using epifluorescence microscopy (BX50, Olympus Corp.) and counted 100 microscopic fields per filter sample.

Doubling time and growth rate constant are index for microbial growth rate, and generally calculated from the data during the exponential growth phase having a constant interval of cell dividing (Powell 1956). Our experiment did not provide the time course population growth and we could not determine the exponential growth phase precisely. In this study, we used the initial and final microbial cell densities by regarding that they were in exponential phase. The incubation time was counted from the time of the chamber deployed on seafloor. The generation time, doubling time, and growth rate constant are calculated from the following equation:

N 0 : initial cell density, N t : cell density at the end of indubation

2.4 16S rRNA Gene Based Analysis by DGGE and DNA Sequencing

The chamber-incubated-microbes were precipitated by centrifugation. Crude DNA of the microbial cell was extracted by phenol-chloroform-isoamylalcohol solution and purified with a GFX genomic blood DNA purification kit (Amersham Pharmacia biotech, USA). Digestive tract contents and gill tissue specimens were collected from dissected sample of Bathymodiolus platifrons, and washed in TE-buffer (10 mM Tris-hydrochloride, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0)) and DNA was extracted according to a previously described method (Yamamoto et al. 2002). Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) was performed on a D-code apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Extracted and purified DNA was used as templates for amplification by the universal DGGE primers targeted to V3 region of 16S rRNA gene of domain Bacteria (341F-GC: 5′-CGCCCGCCGCGCGCGGCGGGCGGGGCGGGGGCACGGGGGGCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG and 534R:5′-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG). The annealing temperature was set at 10 °C above the expected annealing temperature and lowered with 1 °C every second cycle until a touchdown at 55 °C (30 cycle) (Muyzer et al. 1993). PCR products were loaded onto 10 % (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels (37.5:1, acrylamide-bisacrylamide) in 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE), (containing 40 mM Tris, 20 mM acetic acid, and 1 mM EDTA) with a denaturing gradient ranging from 30 to 55 % denaturant (100 % denaturant contains 7 M urea and 40 % (vol/vol) formamide in 1× TAE). The PCR amplicons were electrophoresed at 60 °C and 200 V for 3.5 h. The gel was stained with SYBR Green I (Molecular Probes) for 30 min. DGGE bands were excised from the gel and re-amplified using the aforementioned primer set. The PCR products were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Germany). The sequences of the DGGE bands were determined for both strands using an ABI model 377 (Applied Biosystems, USA) or a CEQ2000XL DNA analysis system (Beckman Coulter, USA). The sequence data were checked for chimeric artifacts and were analyzed by a modular system for evolutionary analysis, MESQUITE v2.75 (http://mesquiteproject.org) (Maddison 2004).

2.5 Physicochemical Conditions

The conductivity, temperature, and pressure were determined by SBE 911 plus (Sea-Bird Electronics, Inc.) or Micro-CTD (Falmouth Scientific, Inc.). The turbidity was measured by turbidity meter (Seapoint, Inc.). We also used a pH sensor which uses an ion-sensitive field- effect transistor (ISFET) as the pH electrode, and a chloride ion selective electrode (Cl-ISE) as the reference electrode (Shitashima et al. 2008). The concentration of H2S was measured with colorimetry using the methylene blue method (Guenther et al. 2001). Determination of CH4 was conducted using an automated CH4 analysis system (DKK corporation, GAS-1061), which consists of a purge unit, a trap unit, and a gas chromatograph with FID (flame ionization detector) after separation by a packed column (Porapak Q 60/80 mesh, 3 mm i.d. × 4 m) (Ishibashi et al. 1997). Sensitivity of the FID was calibrated every day using a working standard gas from which CH4 concentration had determined. Dissolved total mercury was determined by cold-vapor atomic absorption spectrometry (CVAAS). Dissolved mercury is reduced to zerovalent Hg (Hg0) by SnCl2 under the acid condition. The zerovalent mercury ion has low solubility and rapidly vaporized by air bubbling. Vaporized mercury is introduced to detection cell and measured the absorbance in 253.7 nm. We used a CVAAS system (RA-3220, Nippon Instruments Co.) and vaporized procedure was modified with Bloom and Crecelius (1983)(Bloom and Crecelius 1983). 5 mL of seawater sample were mixed with 0.5 mL of 50 % H2SO4 (analytical grade, Kanto Chemical) and 0.5 mL of 10 % SnCl2 (analytical grade, Kanto Chemical) in closed glass vial. We started the bubbling with mercury free air and logging of Hg0 absorbance (253.7 nm) just after the reagents addition. 1,000 ppm HgCl2 standard solution for atomic absorption spectrometry (Kanto Chemical) diluted for calibration. To prevent mercury oxidation and/or reduction during storage of standard solution, L-cysteine was added into each standard solution.

2.6 Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

The nucleotide sequences of 16S rRNA genes amplified from the DGGE bands (150–190 bp) have been deposited in the DDBJ database under accession numbers AB207847 to AB207866.

3 Results

3.1 Environmental Conditions of Hydrothermal Vent Site

Physicochemical factors were measured in NT04-03 cruise. Ambient temperature during in situ incubation on vent fauna habitat fluctuated between 3.9 °C and 4.9 °C with an interval corresponding to tidal cycle (Suppl. 33.2). High concentration of methane (45 μmol kg−1) and hydrogen sulfide (2 mM) dissolved in the vent fluid were detected in the mixing zone of vent side and in the plume of Hatoma Knoll (Table 33.1). The vent plume at 1-m height from vent showed physical and chemical anomaly in cell count, turbidity, total Hg and methane. The high concentration of hydrogen sulfide was detected in the vent fluid and two samples of the hydrothermal plum from 1,476 and 1,400 m. The 324 nmol kg−1 of methane concentration was detected, and δ13C of the methane was range within 49 ‰. A 56 ppt of total Hg was detected even at 1,400 m in water depth. The signatures of hydrothermal fluid clearly declined at water depth of 1,365 m.

3.2 Estimation of the Growth Rate Using Diffusion Chamber System

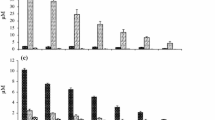

The in situ incubation experiments using the diffusion chambers were carried out in three cruises under different settings (Table 33.2). The onboard preservation time of a prepared chamber and a seeds-water was varied from 16 to 18 h for next submersible dive to deploy the chambers onto seafloor. In the result of NT01-05 cruise, the filtered seed-water induced an effect to shorten the doubling time, and similar effect was detected in the following experiments in NT04-03. The results of NT02-07 showed longer doubling time, 31–32 h, in two times longer incubation days than the case of NT01-05. The results of NT04-03 showed that the most rapid rate, 21 h, was recorded from the chambers placed at vent side, while the growth rate slowed down significantly to 110 h at Bathymodiolus colony in 3–5 m distance from hydrothermal vent (Fig. 33.1). The microbial growth in the chambers inoculated with seed-water from the surface (5 m depth) failed completely under hydrothermal vent conditions in 1,449 m depth on Hatoma Knoll, while they grew under methane seep field in 641 m depth on Kuroshima Knoll.

3.3 Phylogenetic Analysis of Indigenous Bacteria

The seed-waters contained many bacterial taxon groups and the physicochemical condition in mixing zone accelerated the growth of several group in the chambers (Fig. 33.2). The bacterial phylogeny of 16S rRNA gene isolated in the DGGE bands from the samples of incubated chambers and the specimens of B. platifrons shown that three taxa, Mollicutes, Gammaproteobacteria, and Epsilonproteobacteria were dominant groups (Fig. 33.3). The 16S rRNA gene sequences belonging to Mollicutes were found only in the specimens from digestive tract of B. platifrons. The 16S rRNA gene sequences belonging to methanotroph of Gammaproteobacteria were only isolated from B. platifrons, and no thioautotroph type of Gammaproteobacteria appeared in the chambers incubated under the condition of mixing zone on the vent area. The 16S rRNA gene sequences belonging to Epsilonproteobacteria were discovered from specimens of the digestive tract and the chambers incubated with seed water from plume and Bathymodiolus colony.

Cladogram of phylogenetic clusters for 16S rRNA sequences. The sequences with asterisk are DNA from DGGE gel in this study. Abbreviation of the sequences: “Gill” is the gill tissue, “Gut” is the content of digestive tract, “P” is the chamber samples incubated with seed-water of plume, “C” is the chamber samples incubated with seed-water from Bathymodiolus colony

4 Discussion

The data of microbial growth rate of deep-sea zone were previously determined by a simulated in situ incubation system equipped in laboratory. As shown in Table 33.3, the microbial growth rate in ocean gradually declined with water depth (Carlucci and Williams 1978; Lochte and Turley 1988). The oligotrophic growth of indigenous bacteria in unsupplemented seawater of North Pacific Ocean was quite longer doubling time, 145 h, under 1,500 m depth pressured condition (Carlucci and Williams 1978). In the same depth zone of hydrothermal vent area in Hatoma Knoll, the doubling time at non-vent site distant from the active vent were estimated from 86 to 110 h, while at active vent sites 21–32 h doubling time were estimated. The phytodetritus and marine snow provides eutrophic microhabitat for microbial community. The microbial growth determined in such microhabitats under simulated deep-sea condition showed quite rapid doubling times from 10 to 11 h (Lochte and Turley 1988). The photosynthetic product is an effective substrate of bacterial community in pelagic ocean, but its efficiency to sustain the population size declined with water depth (Steinberg et al. 2008).

The bacterivorous protozoa are common member of microbial community even in deep-sea zone (Turley and Carstens 1991; Turley et al. 1988). In this study, although any protozoa by microscopic observation could not be observed, probably due to small population size in the sample, the evidence of bacterivorous activity in hydrothermal system was detected as rapid growth rate in the result of chamber incubation inoculated with filtered seed-water, which was eliminated protozoan sized cells. The microbes of surface seawater did not grow in the chambers placed on the hydrothermal vent field, while grow on the methane seep area on Kuroshima Knoll. The toxicity of hydrogen sulfide and mercury (Pracejus and Halbach 1996) in hydrothermal fluid may be an effective agent to regulate the microbial growth, rather than the water depth and temperature.

The growth rate of thermophiles inhabiting an 85 °C geothermal pool has been measured by the similar in situ diffusion chamber tool, and recorded a range from 20 to 39 h doubling time under 0.2 mM sulfide in geothermal fluid (Kimura et al. 2010). This range was a comparable result determined in 2 mM sulfide in the hydrothermal vent of Hatoma Knoll. While the phylogenetic composition and the physical conditions are quite different between geothermal and hydrothermal systems, they showed very similar range of the doubling times.

The onboard preservation time of the prepared chamber and the seeds-water was unavoidable technical issue of deep-sea submersible operation. This factor may induce unlike physiological condition and be affected the results of growth rate estimation, although the inoculation of seeds-water was performed just before each dive operation. To determine accurate growth rate, the time course in situ experiment with frequent sampling will be needed.

The the 16S rRNA gene sequences of potential sulfur-oxidation bacteria belonging to Epsilonproteobacteria were detected in the chambers incubated with plume water and colony water (Fig. 33.3), while the sequences of Gammaproteobacteria appeared in the chamber incubated with the colony water. The Epsilonproteobacteria have been known as common member discovered from benthic mixing zone of hydrothermal system (Campbell et al. 2006), and a majority of epibiotic microbial community on Sinkaia crosnieri (Tsuchida et al. 2010; Watsuji et al. 2010). The free-living Gammaproteobacteria, SUP05 potential sulfur oxidizing phylotype, dwelled in hydrothermal system have been discovered as common member in chemoautotrophic group of hydrothermal plume (Dick et al. 2013; Sunamura et al. 2004). The different ecophysiological functions between Epsilonproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria probably induced the habitat segregation within hydrothermal system (Nakagawa and Takai 2008; Yamamoto and Takai 2011).

The clade of Epsilonproteobacteria consists of many ecotypes include symbiont with marine invertebrates (Dubilier et al. 2008; Tokuda et al. 2008; Tsuchida et al. 2010), pathogen or normal flora of animals, and free-livings (Campbell et al. 2006). In this study, the 16S rRNA gene sequences of Epsilonproteobacteria from a digestive tract of the Bathymodiolus have either possibility of a feed from mixing-zone bacterial population or a member of normal flora (Egas et al. 2012; Van Horn et al. 2011). Another digestive tract associated the 16S rRNA gene sequences belonging to Mollicute were probably parasitic or potential pathogenic group for mollusks (King et al. 2012; Van Horn et al. 2011; Waltzek et al. 2012).

Methane is proposed as a significant energy source of microbial growth in hydrothermal system (McCollom 2000). The 16S rRNA gene sequence of methane-oxidizing bacteria were detected only from gill and digestive tract, and could not detect from the chamber, despite the chamber was placed on the Bathymodiolus colony. The reasons why the chamber incubation did not allow the growth of methane-oxidizing bacteria was unknown whether caused by methane-permeability of membrane filter or environment constrain for proliferation, or some others.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggested that chemoautotrophic growth in the hydrothermal vent area has an equivalent primary production in the surface seawater. Although an extent of vigorous chemosynthetic growth is constrained to the size of hydrothermal system, the primary production from the growth continuously delivers by hydrothermal plume and bottom current into deep-sea benthopelagic environments. Thus, the microbial growth sustained by chemosynthesis is an important element to estimate the productivity of marine ecosystem.

References

Amend JP, Shock EL (1998) Energetics of amino acid synthesis in hydrothermal ecosystems. Science 281(5383):1659–1662

Bergquist DC, Williams FM, Fisher CR (2000) Longevity record for deep-sea invertebrate. Nature 403:499–500

Bloom NS, Crecelius EA (1983) Determination of mercury in seawater at sub-nanogram per liter levels. Mar Chem 14:49–59

Bollmann A, Lewis K, Epstein SS (2007) Incubation of environmental samples in a diffusion chamber increases the diversity of recovered isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol 73(20):6386–6390

Campbell BJ, Engel AS, Porter ML, Takai K (2006) The versatile epsilon-proteobacteria: key players in sulphidic habitats. Nat Rev Microbiol 4(6):458–468

Carlucci AF, Williams PM (1978) Simulated in situ growth rates of pelagic marine bacteria. Naturwissenschaften 65:541–542

Corliss JB et al (1979) Submaraine thermal springs on the Galapagos Rift. Science 203(4385):1073–1083

Dick GJ, Anantharaman K, Baker BJ, Li M, Reed DC, Sheik CS (2013) The microbiology of deep-sea hydrothermal vent plumes: ecological and biogeographic linkages to seafloor and water column habitats. Front Microbiol 4:124

Dubilier N, Bergin C, Lott C (2008) Symbiotic diversity in marine animals: the art of harnessing chemosynthesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 6(10):725–740

Egas C, Pinheiro M, Gomes P, Barroso C, Bettencourt R (2012) The transcriptome of Bathymodiolus azoricus gill reveals expression of genes from endosymbionts and free-living deep-sea bacteria. Mar Drugs 10(8):1765–1783

Furnas MJ (1991) Net in situ grwoth rates of phytoplankton in an oligotrophic, troical shelf ecosystem. Limnol Ecanogr 36(1):13–29

Gebruk AV, Chevaldonne P, Shank T, Lutz RA, Vrijenhoek RC (2000) Deep-sea hydrothermal vent communities of the Logatchev area: diverse biotopes and high biomass. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 80:383–393

Guenther EA, Johnson KS, Coale KH (2001) Direct ultraviolet spectrophotometric determination of total sulfied and iodide in natural waters. Anal Chem 73(14):3481–3487

Higashi Y, Sunamura M, Kitamura K, Nakamura K-I, Kurusu Y, Ishibashi J-I, Urabe T, Maruyam A (2004) Microbial diversity in hydrothermal surface to subsurface environments of Suiyo Seamount, Izu-Bonin Arc, using a catheter-type in situ growth chamber. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 47:327–336

Hobbie JE, Daley RJ, Jasper S (1977) Use of nucleopore filters for counting bacteia by fluorescence microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol 33:1225–12228

Holmes DE, Giloteaux L, Barlett M, Chavan MA, Smith JA, Williams KH, Wilkins M, Long P, Lovley DR (2013) Molecular analysis of the in situ growth rates of subsurface Geobacter species. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:1646–1653

Ishibashi J-I, Wakita H, Okamura K, Nakayama E, Feely RA, Lebon GT, Baker ET, Marumo K (1997) Hydrothermal methane and manganese variation in the plume over the superfast-spreding southern east pacific rise. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 61(3):485–500

Jannasch HW, Mottl MJ (1985) Geomicobiology of deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Science 229:717–725

Karl DM, Wirsen CO, Janasch HW (1980) Deep-sea primary production at the Galapagos hydrothermal vents. Science 207:1345–1347

Kimura H, Mori K, Nashimoto H, Hattori S, Yamada K, Koba K, Yoshida N, Kato K (2010) Biomass production and energy source of thermophiles in a Japanese alkaline geothermal pool. Environ Microbiol 12(2):480–489

King GM, Judd C, Kuske CR, Smith C (2012) Analysis of stomach and gut microbiomes of the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) from coastal Louisiana, USA. PLoS One 7(12):e51475

Kirchman DL (2001) Measuring bacterial biomass production and growth rates from leucine incorporation in natural aquatic environments. Method Microbiol 30:227–237

Lochte K, Turley CM (1988) Bacteria and cyanobacteria associated with phytodetritus in deep sea. Nature 333:67–69

Lonsdale P (1977) Clustering of suspension-feeding macrobenthos near abyssal hydrothermasl vents at oceanic spreding centers. Deep Sea Res 24:857–863

Lutz RA, Shank TM, Fornari DJ, Haymon RM, Lilley MD, Von Damm KL, Desbruyeres D (1994) Rapid growth at deep-sea vents. Nature 371:663–664

Maddison DR (2004) Are strepsipterans related to flies? Exploring long branch attraction. Study 2 in Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis, version 1.04. http://mesquiteproject.org

Malmstrom RR, Cottrell MT, Elifantz H, Kirchman DL (2005) Biomass production and assimilation of dissolved organic matter by SAR11 bacteria in the Northwest Atlantic Ocean. Appl Environ Microbiol 71(6):2979–2986

McCollom TM (2000) Geochemical constraints on primary productivity in submarine hydrothermal vent plumes. Deep Sea Res I 47:85–101

McCollom TM, Shock EL (1997) Geochemical constraints on chemolithoautotrophic metabolism by microorganisms in seafloor hydrothermal systems. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 61(20):4375–4391

McFeters GA, Stuart DG (1972) Survval of coliform bacteria in natural waters: field ad laboratory studies with membrane-filter chambers. Appl Microbiol 24(5):805–811

Muyzer G, De Waal EC, Uitterlinden AG (1993) Profiling of complex microbial population by denaturing gradient gel eclectrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction- amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol 59(3):695–700

Nakagawa S, Takai K (2008) Deep-sea vent chemoautotrophs: diversity, biochemistry and ecological significance. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 65(1):1–14

Newell SY, Christian RR (1981) Frequency of dividing cells as an estimator of bacterial productivity. Appl Environ Microbiol 42(1):23–31

Powell EO (1956) Growth rate and generation time of bacteria, with special reference to continuous culture. J Gen Microbiol 15:492–511

Pracejus B, Halbach P (1996) Do marine moulds infuluence Hg and Si precipitation in the hydrothermal JADE field (Okinawa Trough)? Chem Geol 130(87–99)

Reysenbach AL, Longnecker K, Kirshtein J (2000) Novel bacterial and Archaeal lineages from an in situ growth chamber deployed at a mid-Atlantic Ridge hydrothermal vent. Appl Environ Microbiol 66(9):3798–3806

Schmidt C, Vuillemin R, Le Gall C, Gaill F, Le Bris N (2008) Geochemical energy sources for microbial primary production in the environment of hydrothermal vent shrimps. Mar Chem 108(1–2):18–31

Sherr EB, Sherr BF, Sigmon T (1999) Activity of marine bacteria under incubated and in situ conditions. Aquat Microb Ecol 20:213–223

Shitashima K, Maeda Y, Koike Y, Ohsumi T (2008) Natural analogue of the rise and dissolution of liquid CO2 in the ocean. Int J Greenhouse Gas Control 2(1):95–104

Steinberg DK, Van Mooy BAS, Buesseler KO, Boyd PW, Kobari T, Karl DM (2008) Bacterial vs. zooplankton control of sinking particle flux in the ocean’s twilight zone. Limnol Ecanogr 53(4):1327–1338

Sunamura M, Higashi Y, Miyako C, Ishibashi JI, Maruyama A (2004) Two bacteria phylotypes are predominant in the Suiyo seamount hydrothermal plume. Appl Environ Microbiol 70(2):1190–1198

Takai K, Inagaki F, Nakagawa S, Hirayama H, Nunoura T, Sako Y, Nealson KH, Horikoshi K (2003) Isolation and phylogenetic diversity of members of previously uncultivated epsilon-Proteobacteria in deep-sea hydrothermal felds. FEMS Microbiol Lett 218:164–174

Taylor CD, Wirsen CO, Gaill F (1999) Rapid microbial production of filamentous sulfur mats at hydrothermal vents. Appl Environ Microbiol 65(5):2253–2255

Tokuda G, Yamada A, Nakano K, Arita NO, Yamasaki H (2008) Colonization of Sulfurovum sp. on the gill surfaces of Alvinocaris longirostris, a deep-sea hydrothermal vent shrimp. Mar Ecol 29(1):106–114

Torrton J-P, Dufour P (1996) Bacterioplankton production determined by DNA synthesis, protein synthesis, and frequency of dividing cells in Tuamotu Atoll Lagoons and surounding ocean. Microb Ecol 32:185–202

Tsuchida S, Suzuki Y, Fujiwara Y, Kawato M, Uematsu K, Yamanaka T, Mizota C, Yamamoto H (2010) Epibiotic association between filamentous bacteria and the vent-associated galatheid crab, Shinkaia crosnieri (Decapoda: Anomura). J Mar Biol Assoc U K 91(01):23–32

Turley CM, Carstens M (1991) Pressure tolerance of oceanic flagellates: implications for remineralization of organic matter. Deep Sea Res 38:403–413

Turley CM, Lochte K, Patterson DJ (1988) A barophilic flagellate isolated from 4500 m in the mid-North Atlantic. Deep Sea Res 35(7):1079–1092

Van Horn DJ, Garcia JR, Loker ES, Mitchell KR, Mkoji GM, Adema CM, Takacs-Vesbach CD (2011) Complex intestinal bacterial communities in three species of planorbid snails. J Molluscan Stud 78(1):74–80

Vasconcelos GJ, Swartz RG (1976) Sruvival of bacteria in seawater using a diffusion chamber apparatus in situ. Appl Environ Microbiol 31(6):913–920

Waltzek TB, Cortes-Hinojosa G, Wellehan JF Jr, Gray GC (2012) Marine mammal zoonoses: a review of disease manifestations. Zoonoses Public Health 59(8):521–535

Watanabe K (2001) Mapping the hydrothermal activity area on the Hatoma Knoll in the southern Okinawa Trough. JAMSTEC J Deep Sea Res 19:87–94

Watsuji T-O, Nakagawa S, Tsuchida S, Toki T, Hirota A, Tsunogai U, Takai K (2010) Diversity and function of epibiotic microbial communities on the Galatheid Crab, Shinkaia crosnieri. Microb Environ 25(4):288–294

Williams PM, Carlucci AF (1976) Bacterial utilisation of organic matter in the deep sea. Nature 262:810–811

Yamamoto M, Takai K (2011) Sulfur metabolisms in epsilon- and gamma-proteobacteria in deep-sea hydrothermal fields. Front Microbiol 2:192

Yamamoto H, Fujikura K, Hiraishi A, Kato K, Maki Y (2002) Phylogenetic characterization and biomass estimation of bacterial endosymbionts associated with invertebrates dwellin in chemosynthetic communities of hydrothermal vent and cold seep fields. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 245:61–67

Yokokawa T, Nagata T, Cottrell MT, Kirchman DL (2004) Growth rate of the major phylogenetic bacterial groups in the Delaware estuary. Limnol Ecanogr 49(5):1620–1629

Acknowledgement

We thank the captain and crew of R/V Natsushima and the deep-sea submersible operation teams of Hyper-Dorphin 3000 and Shinkai 2000 for helping us to complete sample collection and in situ experiments. This work was partially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (no. 20109003) and the Archaean Park Program from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MEXT). Thanks are also due to the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for the stay of L. G. Tóth.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

1 Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

317349_1_En_33_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Suppl. 33.1 Spatial profile of hydrothermal plume and microbial and geochemical data on hydrothermal vent of Hatoma Knoll. The ambient temperature of vent community fluctuated between 3 and 5 °C with an interval corresponding to tidal cycle. High concentration of methane detected in vent plume, even detectable at 100 m above from the vent site. Hydrogen sulfide detected in the thermal fluid, and the concentration in the plume drastically declined to undetectable range (<1 ppm). These chemicals are fundamental energy source of the prokaryotes in the hydrothermal system. The above figure was illustrated using the data set of Table 33.1

317349_1_En_33_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Suppl. 33.2 Fluctuation of water temperature during in situ incubation experiments on Hatoma Knoll and Kuroshima Knoll. The compact thermometer (MDS-MkV/T, JFE Advantech Co., Ltd.) was attached on the canister for determination of temperature fluctuation during in situ incubation experiments. In case of Hatom Knoll, thermometers were attached at top and bottom of the canister. The ambient temperature of hydrothermal vent sites fluctuated between 3 and 5 °C with an interval corresponding to tidal cycle. On Kuroshima Knoll, the ambient temperature fluctuated between 6 and 9 °C

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License, which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Copyright information

© 2015 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Yamamoto, H. et al. (2015). In Situ Determination of Bacterial Growth in Mixing Zone of Hydrothermal Vent Field on the Hatoma Knoll, Southern Okinawa Trough. In: Ishibashi, Ji., Okino, K., Sunamura, M. (eds) Subseafloor Biosphere Linked to Hydrothermal Systems. Springer, Tokyo. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-54865-2_33

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-54865-2_33

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Tokyo

Print ISBN: 978-4-431-54864-5

Online ISBN: 978-4-431-54865-2

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)