Abstract

The Great Han Empire began to decline at the beginning of the second century A.D. It was finally broken up in A.D. 220, and then came a period of civil strife followed by foreign invasions that lasted for almost 400 years. In order that the status of Chi should be properly understood, a general survey of the succession of the minor dynasties in this period of confusion is unavoidable.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution.

Buying options

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Learn about institutional subscriptionsNotes

- 1.

Each of the Three Kingdoms represented a natural geographic region. In the North, based on the middle valley of the Yellow River and inheriting the frontier problems of war and trade with the northern nomads, was the Kingdom of Wei. In the South, along the Yangtze River, there was the Kingdom of Shu in the Red Basin above the great gorge and the Kingdom of Wu in the middle and lower valley below it.

- 2.

They are the Sung (宋, 420–479), Ch’i (齐, 479–502), Liang (梁, 502–557) and Ch’en (陈, 557–588) dynasties. All ruled from the same capital of the present city Nanking.

- 3.

The five nomadic peoples are generally known as Hsiung-nu (匈奴), Hsien-pei (鲜卑), Chieh (羯), Ti (狄) and Ch’iang (羌). Hsiung-nu is the Chinese name for the Western Tartars of Mongolia who are believed to be the ancestor of the Huns and Turks. Hsien-pei, Chieh and Ti are probably different tribes of the Mongols. Chiang is a tribe of Tibetan nomads.

- 4.

This indicates the route of the invasion of the Toba nomads who came from the north and northwest and naturally took Ping-ch’eng (Ta-t’ung) instead of Chi (Peiping) as their first base in China. Compare with the route of the invasion of the Mu-jung nomads from the northeast in the following discussion.

- 5.

The route of invasion of Mu-jung Chün (慕容俊), the founder of the Yen state, is mentioned in the Tsin Shu, Tsai-chi (《晋书·载记》, the Historical Records of the Tsin dynasty) as follows: ‘In the fifth year of Yung-ho (永和, 349) during the reign of the emperor Mu (穆), Mu-jung Chün assumed the title of the King of Yen. In the next year (350), he marched out his troops southward through Lu-lung (卢龙) and stopped at Wu-chung (无终). Wang Wu (王午), the provincial governor of Yu Chou appointed by Shih Chi-lung (石季龙), escaped from the city of Chi. He left it to his general Wang T’a (王他) to defend. (Mu-jung) Tsün attacked the city and captured it. Wang T’a was executed and the city was made the capital’. It was quoted by Yü Min-chung (于敏中) in Jih-hsia Chiu-wen K’ao (《日下旧闻考》), 2/19b. Both places, Lu-lung and Wu-chung, were situated along the great highway between the present Shan-hai Kwan and Chi.

- 6.

G. B. Cressey [1, p. 169].

- 7.

Irrigation is essential for rice cultivation in normal years, but it is also essential for wheat and millet cultivation during drought. In some parts well irrigation is used where rivers and springs are not available.

- 8.

The best example is the Wei Ho Valley. See Chi Ch’ao-ting [2, Chapter V].

- 9.

See the Historical Chart of Peiping, Appendix I.

- 10.

Li Tao-yüan (郦道元), Shih Ching Chu (《水经注》, Commentaries on the Book of Rivers), Ssu-pu Pei-yao edition, 14/7a-b. See also Ch’en Shou (陈寿), San Kuo Chih, Wei Chih (《三国志·魏志》, History of the Three Kingdoms, Section on the Kingdom of Wei), and Liu Ching Chuan (《刘靖传》, Biography of Liu Ching).

- 11.

Li Tao-yüan, op. cit., 14/7b-8a.

- 12.

See Appendix I, Historical Chart of Peiping.

- 13.

The above account concerning the original irrigation project and its later extension is derived from a most valuable record which has been preserved in the Commentaries on the Book of Rivers (14/7a-8b). It is the text of the inscription of a stone monument erected in the year 295 inside the east gate of Chi, to commemorate the great services rendered to the local inhabitants by Liu Ching and his successors. The monument is known as Liu Ching Pei (刘靖碑, The Stone Tablet of Liu Ching).

- 14.

Wei Shu (《魏书》, The Dynastic History of the Northern Wei), Pei Yen-chün Chuan (《裴延俊传》, Biography of Pei Yen-chün), Ssu-pu Pei-yao edition, 69/3a-b. For the date of this reconstruction, see Ku Tsu-yü, op. cit., 11/3a.

- 15.

Pei Ch’I Shu (《北齐书》, The Dynastic History of the Northern Ch’i), Hu-lü Hsien Chuan (《斛律羡传》, Biography of Hu-lü Hsien), Ssu-pu Pei-yao edition, 17/5b.

- 16.

See Appendix IV.

- 17.

Wu-ch’ing was then called Yung-nu (雍奴). See Li Tao-yüan, op. cit., 13/22a-b.

- 18.

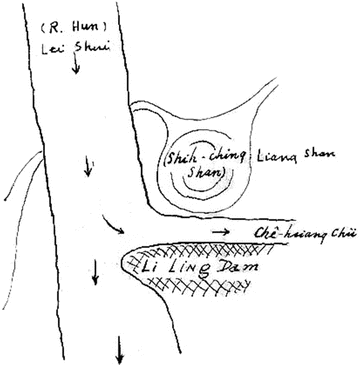

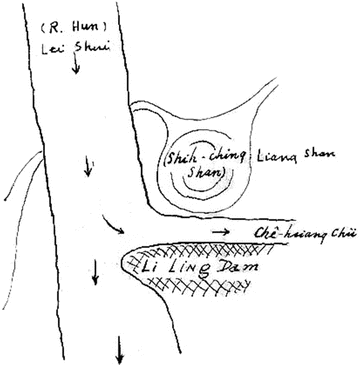

There is a description of the method of construction of the Li Ling Dam in Shui Ching Chu, but it is not easy to understand owing to the obscure terms it used. Anyhow, a rough diagram may be given here to show the probable way of its construction. Now, on the very spot stands the modern construction to draw water from the river for irrigation in the adjacent area. This is the Shih-Lu Irrigation Canal (石芦灌溉沟渠, from Shih-ching Shan to Lu-kow Bridge).

- 19.

The abandoned river bed of a canal of the twelfth century, called Chin Kou (金口, see Chap. 6), can still be seen in the west environs of the present city. It was dug through these isolated hills—a course which was most probably based upon the ruin of the Ch’e-hsiang Ch’ü.

- 20.

See Footnote 10 on p. 35.

- 21.

Pei Ch’I Shu, 17/5b.

References

Cressey, G. B. (1934). The geographic foundations of China. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

Chi Ch’ao-ting. (1936). Key economic areas in Chinese history. London: George Allen & Unwin, Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Foreign Language Teaching and Research Publishing Co., Ltd and Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hou, R. (2014). Chi in the Dark Ages Prior to the Unification of Sui (221–589), with Special Reference to the Development of Local Irrigation. In: An Historical Geography of Peiping. China Academic Library. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-55321-9_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-55321-9_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-55320-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-55321-9

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawSocial Sciences (R0)