Abstract

A speaker does position expansion when they are making an agreeing opinion statement in response to a prior speaker’s opinion statement in such a way that the action in the current turn takes over the sequential relevancies established in prior speaker’s turn. This is an interaction-structure re-organizing type of action at the level of the local management of social relations between participants in a multi-person setting. Position expansions are designed as constructionally dependent and-prefaced continuations of the final turn constructional unit in prior speaker’s turn. The device enables a second speaker to retroactively demonstrate their claim to form a group with prior speaker. Position expansion is an alternative way of doing agreement that makes the speaker’s organisational agenda manifest.

This paper is partially based on Mazeland (2009), and on presentations at several conferences in the years thereafter, the last one in the Activities panel organised by Cornelia Gerhardt and Elisabeth Reber at IPrA, Belfast in July 2017. I thank Anja Stukenbrock for her comments at the MeMI-network workshop, ZIF Bielefeld 2014. I also thank Erik Spikmans for making the drawings of the video stills.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

Egbert (1997) distinguishes between multi-person and multi-party interaction. Although the latter category is often relevant for the analysis of meeting data, I start with a characterization of the meeting data as a type of multi-person interaction.

- 2.

Schegloff (1996a and 2016) characterises ‘increments’ of a possibly complete TCU with the following features: (1) a speaker has brought a TCU to possible completion ; (2) there is further talk by the same speaker; (3) the further talk is grammatically dependent of the prior TCU, i.e. it re-completes it (Schegloff 2016: 241). The continuation in lines 5–6 of Extract 12.1 does not display these features: (1) it is not designed as a (re-)completion of the TCU in the prior turn; (2) the construction of the TCU is not dependent of the lexico-syntactic structure of the TCU in the prior turn; (3) the TCU has a recognizable beginning: both the beginning of the turn, ‘t moet … (it has to …), and its repaired version, ze moeten niet … (they shouldn’t …, line 5), clearly position the subject pronouns ‘t (it) and ze (they) in the sentence-initial position of a clause with verb-second word order. So instead of formatting his turn as an ‘increment continuation’, the speaker shapes it as a ‘TCU-continuation’ (cf. Sidnell 2012), that is, a continuation of his prior turn with another TCU.

- 3.

The turn in lines 5–6 is full of design features that indicate that the speaker is building it as an extension of the action in the preceding turn of the same speaker. Because it is relevant for distinguishing between same-speaker continuation of the same action -unit and other-continuation of the ongoing activity, I list these features below:

-

Prosodic packaging: the turn is prosodically structured as a unit that comprises both the prior and current turns: the final level pitch of the TCU in the prior turn (line 2) projects same-speaker continuation, whereas the final falling pitch of the TCU in the follow-up turn (line 6) marks the possible completeness of the current turn and of the overarching unit.

-

Achieving cohesion with linguistic devices (cf. Halliday and Hasan 1976): The repair of ‘t moet … (it has to) into ze moeten niet (they shouldn’t …) in the beginning of line 5 establishes referential continuity; the repaired reference form they ties back to the referent of the product group in the preceding turn (lines 1–2).

-

Constructional symmetry: both TCUs are formatted as a declarative assertion stating a norm; moreover, both TCUs are shaped as a deontive modal construction with the verb moeten (have to, should).

-

Elaboration and complementarity at the content level (Halliday and Hasan 1976; Levinson 2013). Stating that they should not … consider us as a kind of car dealers (lines 5–6) exemplifies the more general demand in the preceding part of the turn (the arrogant behaviour of the product group has to change, lines 1–3). These two norms are also complementary: The team leader first asserts a general norm for a more desirable future state of affairs, and then accounts for it by asserting a specific norm about what is not acceptable in the current state of affairs.

-

- 4.

Heritage and Sorjonen (1994) describe a similar use of and-prefacing for and-prefaced questions. Such questions do not link the turn to the prior turn, but link the question-answer sequence it is launching to the preceding question-answer sequence as a next step in an ‘activity’ that develops as a succession of question-answer sequences.

- 5.

It is perhaps useful to make a remark about terminology. I am using the notion ‘position’ as a ‘structural’ notion to refer to a slot in an ordered sequence of actions. ‘Sequential position’ is different from ‘turn location ’ (cf. Levinson 1983; Schegloff 2007). ‘Next position’ is a slot for a fitting next action in a sequence of actions; ‘next turn’ refers to the location of a turn in a series of turns. ‘Next turn’ may coincide with ‘next position’, but this is not always and not necessarily the case. I talk about ‘position expansion’ if the next speaker incorporates their response into the sequential position created by the prior speaker’s action ; he or she re-instantiates the sequential position established by the action it is responsive to.

- 6.

My claim that and-prefacing is a necessary feature of the design of position-expansion TCUs is possibly contradicted by the fact that, in the case of the position expansion in Extract 12.2, the speaker treats the and preface as a ‘dispensable’, that is, as an element that may be omitted when a speaker produces the same talk one more time (cf. Schegloff 2004):

Extract 12.2 Detail

Boris starts his turn in overlap with the second syllable of Ciska’s response turn (lines 2–3). He halts its delivery at the end of its second word, en dat- (and that-, line 3), but immediately restarts it free of overlap after Ciska has completed her response (cf. Schegloff 1987). Although Boris recognizably recycles the same turn-beginning as the one he just abandoned—compare en dat (and that) and dat (that) in line 3 (cf. Local et al. 2010)—he leaves out the and preface from his restart. Schegloff’s explanation for this type of dispensable is that the sequential environment to which the speaker was initially tying their turn has changed (Schegloff 2004). The indispensability of an element is evidence for it being a constitutive feature of the action in the repeated TCU; see, for example, Bolden (2010: 15). I am not sure whether its dispensability is evidence for the reverse claim.

- 7.

The type of quotation that Boris attaches to the quotative frame, ik heb zoiets … (I am like …), differs from the one that Jan used in his turn. Whereas Jan formats the quote with his opinion statement as a direct reported ‘thought’ (let us simply decide how we want to have it, line 1 of Extract 12.2), Boris casts his addition as an indirect quote (and that- that we make the picture). A speaker who uses direct reported speech also takes responsibility for the precise wording of the quotation; indirect reported speech does not carry this claim. Boris’s use of indirect speech may be a technique for attributing the primary authorship of their shared opinion to Jan.

- 8.

Oh (2006) shows that zero-anaphora constructions may be used as a practice for maximising the connectedness between successive clauses (Oh 2006: 831), and that the avoidance of a subject reference term casts the current TCU as designed “to be tied to prior talk as a fitted continuation of it” (ibid.: 837).

- 9.

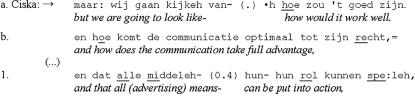

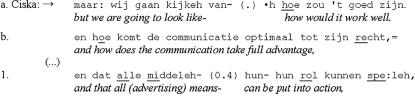

Ciska created the organizational space for a larger project in a multi-unit turn by establishing an open framework for a list of improvements: maar wij gaan kijken van- (but we are going to look like …; see line a in Extract 12.4a below). The particle van after kijken (look) is frequently used after verbs of saying or thinking as an opener for a typifying quotation in Dutch (cf. Mazeland 2006). The list items themselves are shaped as a series of dependent clauses (indirect how-questions in lines a–b in Extract 12.4a below, and a series of that-clauses in lines 1 and 4 of Extract 12.4):

Extract 12.4a Context of Ciska’s series of en dat … (and that-) clauses in lines 1 and 4 in Extract 12.4)

- 10.

Note that the three cases of position expansion I have described in detail tie to a syntactic frame in the host turn that is shaped as a ‘complement-taking predicate’ (Thompson 2002): maar ik heb zoiets van … (but I am like …) in Extract 12.2, ik denk dat … (I think that …) in Extract 12.3, and maar wij gaan kijken van … (but we are going to look like …) in Extract 12.4. These kinds of matrix-sentence frames may host a variety of embedded clauses, often in ways that are more loose than prescriptive grammatical rules allow or predict (see also Günthner 2008; Verhagen 2005). I don’t know whether this is accidental or whether it is a systematic feature of the host turn that facilitates the occurrence of position expansion.

- 11.

In this section I will focus on giving detailed evidence from the position-expansion sequence in Extract 12.2. Comparable evidence from the cases documented in Extracts 12.3–12.4 is only hinted at.

- 12.

“Make the picture” is an idiomatic expression for making a plan; it has likely acquired that meaning on the basis of metonymic reasoning (cf. Lakoff and Johnson 1980). Boris clearly talks within the same activity scenario that Jan’s statement is about. Note also that Boris’s statement has the same topic referent as Jan’s statement, wij (we).

- 13.

I don’t think the term ‘overhearer’ is appropriate for this way of addressing turns in the meeting setting, therefore I have chosen to use the term ‘co-hearer’ as a type of recipient that is different from the ‘primary recipient’.

- 14.

Mary’s collaborative TCU-completion in line 2 of Extract 12.10 exploits the projection that is based on the current speaker’s use of a verb form from the set Dutch verbal expression [nodigadj hebbenverb]/ have a-need-for + complement. The speaker of the anticipatory completion provides the [adjective + complement] part of this multi-word verb construction.

- 15.

Note that the original speaker of the turn-so-far in Extract 12.10 does not treat the proffered completion as a display of understanding or agreement with the action underway. She does not confirm or reject it. Instead she does a ‘delayed completion ’ of her own turn (Lerner 2004: 238) that deletes the anticipatory completion of her colleague from the interactional surface (line 3). It restores the conditional relevance of a response to the action in her turn (see lines 4–8 in Extract 12.10).

References

Asmuß, Birte, and Sae Oshima. 2012. Negotiation of entitlement in proposal sequences. Discourse Studies 14 (1): 67–86.

Boden, Deidre. 1994. The business of talk: Organizations in action. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bolden, Galina B. 2010. ‘Articulating the unsaid’ via and-prefaced formulations of others’ talk. Discourse Studies 12 (1): 5–32.

Button, Graham, and Wes Sharrock. 2000. Design by problem-solving. In Workplace studies: Recovering work practice and informing system design, ed. Paul Luff, Jon Hindmarsh, and Christian Heath, 46–67. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Couper-Kuhlen, Elizabeth, and Tsuyoshi Ono. 2007. Incrementing in conversation: A comparison of practices in English, German and Japanese. Pragmatics 17 (4): 513–552.

Egbert, Maria. 1997. Schisming: The collaborative transformation from a single conversation to multiple conversations. Research on Language and Social Interaction 30 (19): 1–51.

Goffman, Erving. 1981. Footing. In Forms of talk, ed. Erving Goffman, 124–159. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Goodwin, Charles. 2013. The co-operative, transformative organization of human action and knowledge. Journal of Pragmatics 46 (1): 8–23.

Günthner, Susanne. 2008. ‘Die Sache ist …’: Eine Projektorkonstruktion im Gesprochenen Deutsch. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 27: 39–71.

Halliday, M.A.K., and Ruqaiya Hasan. 1976. Cohesion in English. London: Longman.

Heritage, John, and Marja-Leena Sorjonen. 1994. Constituting and maintaining activities across sequences: And-prefacing as a feature of question design. Language in Society 23 (1): 1–29.

Houtkoop-Streenstra, Hanneke, and Harrie Mazeland. 1985. Turns and discourse units in everyday conversation. Journal of Pragmatics 9: 595–619.

Huisman, Marjan. 2001. Decision-making in meetings as talk-in-interaction. International Studies of Management & Organization 31 (3): 69–90.

Jefferson, Gail. 1986. Notes on ‘latency’ in overlap onset. Human Studies 9 (2–3): 153–184.

Kangasharju, Helena. 2002. Alignment in disagreement: Forming oppositional alliances in committee meetings. Journal of Pragmatics 34 (10): 1447–1471.

Kendon, Adam. 1977. Studies in the behaviour of social interaction. Lisse: Peter de Ridder Press.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors we live by. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Lerner, Gene. 1991. On the syntax of sentences-in-progress. Language in Society 20 (3): 441–458.

Lerner, Gene. 1993. Collectivities in action: Establishing the relevance of conjoined participation in conversation. Text 13 (2): 213–245.

Lerner, Gene. 1996. Finding face in the preference structures of talk-in-interaction. Social Psychology Quarterly 59 (4): 303–321.

Lerner, Gene. 2004. Collaborative turn sequences. In Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation, ed. Gene Lerner, 225–255. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Levinson, Stephen. 1983. Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Levinson, Stephen. 2013. Action formation and ascription. In The handbook of conversation analysis, ed. Jack Sidnell and Tanya Stivers, 103–130. Oxford: Blackwell.

Local, John, and Gareth Walker. 2012. How phonetic features project more talk. Journal of the International Phonetic Association 42 (03): 255–280.

Local, John, Paul Drew, and Peter Auer. 2010. Retrieving, redoing, and resuscitating turns in conversation. In Prosody in interaction, ed. Dagmar Weingarten-Barth, Elisabeth Reber, and Margret Selting, 131–160. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Mazeland, Harrie. 2006. ‘VAN’ as a quotative in Dutch: Marking quotations as a typification. In Artikelen van de vijfde sociolinguïstische conferentie, ed. Tom Koole et al., 354–365. Delft: Eburon.

Mazeland, Harrie. 2009. Positionsexpansionen: Die interaktive Konstruktion von Stellungnahme-Erweiterungen in Arbeitsbesprechungen. In Grammatik im Gespräch: Konstruktionen der Selbst- und Fremdpositionierung, ed. Susanne Günthner and Jörg Bücker, 185–214. Berlin and New York: de Gruyter.

Mazeland, Harrie, and Mike Huiskes. 2001. Dutch but as a sequential conjunction: Its use as a resumption marker. In Studies in interactional linguistics, ed. Margret Selting and Elizabeth Couper-Kuhlen, 141–169. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Oh, Sun-Young. 2005. English zero-anaphora as an interactional resource. Research on Language and Interaction 38 (3): 267–302.

Oh, Sun-Young. 2006. English zero anaphora as an interactional resource II. Discourse Studies 8 (6): 817–846.

Ono, Tsuyoshi, and Sandra A. Thompson. 1997. Deconstructing ‘zero anaphora’ in Japanese. Berkeley Linguistic Society 23: 481–491.

Sacks, Harvey. 1987. On the preferences for agreement and contiguity in sequences in conversation. In Talk and social organization, ed. Graham Button and John R.E. Lee, 54–69. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Sacks, Harvey. 1992. Lectures on conversation, vol. I, ed. Gail Jefferson. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sacks, Harvey, Emanuel A. Schegloff, and Gail Jefferson. 1974. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language 50 (4): 696–735.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1968. Sequencing in conversational openings. American Anthropologist 70 (6): 1075–1095.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1987. Recycled turn beginnings: A precise repair mechanism in conversation’s turn-taking organization. In Talk and social interaction, ed. Graham Button and John R.E. Lee, 70–85. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1991. Reflections on talk and social structure. In Talk and social structure: Studies in ethnomethodology and conversation analysis, ed. Deirdre Boden and Don H. Zimmerman, 44–70. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1996a. Turn organization: One intersection of grammar and interaction. In Interaction and grammar, ed. Elinor Ochs, Emanuel A. Schegloff, and Sandra A. Thompson, 52–133. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1996b. Confirming allusions: Toward an empirical account of action. American Journal of Sociology 102 (1): 161–216.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2000. Overlapping talk and the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language in Society 29 (1): 1–63.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2004. On dispensability. Research on Language and Social Interaction 37 (2): 95–149.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2007. Sequence organization in interaction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schegloff, Emanuel A. 2016 [2001/2007]. Increments. In Accountability in social interaction, ed. Jeffrey D. Robinson, 239–263. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, Sandra A. 2002. “Object complements” and conversation. Towards a realistic account. Studies in Language 26 (1): 125–163.

van der Schoot, Mirjam, and Harrie Mazeland. 2005. Probleembeschrijvingen in werkbesprekingen. Tijdschrift voor Taalbeheersing 27 (1): 1–23.

Selting, Margret. 1996. On the interplay of syntax and prosody in the constitution of turn-constructional units and turns in conversation. Pragmatics 6 (3): 371–388.

Selting, Margret. 2007. Lists as embedded structures and the prosody of list construction as an interactional resource. Journal of Pragmatics 39 (3): 483–526.

Sidnell, Jack. 2012. Turn-continuation by self and other. Discourse Processes 49 (3–4): 314–337.

Stevanovic, Melisa. 2012. Establishing joint decisions in a dyad. Discourse Studies 14 (6): 779–803.

Verhagen, Arie. 2005. Constructions of intersubjectivity: Discourse, syntax, and cognition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Mazeland, H. (2019). Position Expansion in Meeting Talk: An Interaction-Re-organizing Type of and-Prefaced Other-Continuation. In: Reber, E., Gerhardt, C. (eds) Embodied Activities in Face-to-face and Mediated Settings. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97325-8_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97325-8_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-97324-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-97325-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)