Abstract

In this work, a photonic physical unclonable function module, based on an optical waveguide, is demonstrated. The physical scrambling mechanism is based on the random and complex coherent interference of high order optical transverse modes. The proposed scheme allows the generation of random bit- strings, through a simple wavelength tuning of the laser source, that are suitable for a variety of cryptographic applications. The experimental data are evaluated in terms of unpredictability, employing typical information theory benchmark tests and the NIST statistical suit.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The rapid development of technology and the advent of Internet of Things (IoT) have already rendered the interconnection between heterogeneous devices possible, making the remote access and control of our private information an aspect of our everyday life. However, with the existing forms of hardware security, and taking into consideration the size/cost restriction of such devices, the IoT ecosystem can be compromised by numerous threats, thereby imposing a perpetual hunt of new protection schemes that could be utilized. Within the last decade, Physical Unclonable Functions (PUFs) - a physical feature of an object that it is practically impossible to duplicate, even by the manufacturer - have been proven an innovative approach for the successful solution of the aforementioned issues.

Essentially, a PUF is the hardware analogue of a one-way mathematical function, which is not based on a common hashing transformation but rather on a complex and non-reproducible physical mechanism [1]. Its directionality is preserved through the complexity of the physical system employed, which renders brute force attacks computationally infeasible, while the random physical process involved in its realization nullifies the possibility of cloning. These two key advantages, combined with the deterministic (time-invariant) operation of their physical system, place PUFs as excellent candidates for cryptographic key generation modules, through which keys can be produced on demand, eliminating the need for secure non-volatile storage.

Currently, state of the art devices rely on electronic implementations, mainly depending on the low manufacturing yield of various components like SRAMS, latches etc. However, despite the fact that such schemes are resilient to noise, they have been proven vulnerable to a plethora of machine learning and side channel attacks, which has been attributed to their low physical complexity [2]. Furthermore, implementations that are based on the inherent randomness of nanofabrication procedures, like memristors and surface plasmons [3], have shown great promise and potential, but the technology is still immature.

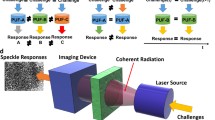

Photonic implementations of PUFs utilize the coherent interaction of a laser beam with a medium characterized by inherent random inhomogeneity. In these implementations, a laser source illuminates (challenge) a transparent material that has a set of randomly positioned scatterers, the goal being the creation of unique interference patterns (speckle) which are subsequently captured as images (responses). As stated explicitly [6] in the literature a significant number of parameters can vastly affect the responses, for example: the angle and number of incident beam(s), their wavelength, and the beam diameter(s).

The recorded images (responses) go through post-processing via a hashing algorithm to produce distinct binary sequences. Their recovery is achieved through a Fuzzy Extractor scheme [4, 5]. The Fuzzy extractor scheme essentially maps every hashed response to a unique bit-string output and it is comprised of two phases; the enrollment and the verification phase. The former corresponds to the first time that a challenge is applied whereby the output string is generated along with a set of public helper data, while the latter represents the error-prone rerun of the measurement during which the same result is recreated by using the helper data produced in the enrollment phase.

The physical complexity of a photonic PUF can be mainly attributed to multiple scattering of light in the Mie regime. The Mie regime concerns particles of similar size compared to the wavelength of the incident radiation, rendering the exact solutions of the Maxwell equations necessary for an adequate description of the resulting electromagnetic (E/M) field distribution. The computational arduousness of this endeavor, combined with the fact that any modification in the inherent structure of the medium or the illumination conditions require a new set of equations, has the effect of the system being highly unpredictable and therefore immune to statistical attacks [6].

In this paper, we propose an alternative PUF configuration, using a transparent optical medium which allows multi-path propagation of the incident laser beam. That medium allows the random excitation and the simultaneous guiding of a high number of transverse optical modes, which can be perceived as the E/M field distribution governed by the Maxwell equations and boundary conditions of the medium [7]. Some representative intensity distribution patterns of transverse modes are presented in Fig. 1. Each mode is characterized by a different propagation constant, which signifies the phase change per length unit. This enables the coherent interaction between the modes (amplitude and phase), generating the unique speckle patterns.

The experimental setup, as illustrated in Fig. 1, employs a tunable single mode laser with a central wavelength of λ = 1540 nm, the waveguide specimen (PUF) and a vidicon camera. The captured images are stored and processed offline, as proposed in [4]. The product of that post-processing are the distinct binary sequences. The suitability of the generated bit-strings to be used as cryptographic keys is evaluated through standard NIST tests and established mathematical metrics like the Hamming/Euclidean distances, conditional information entropy, and minimal conditional entropy.

The use of bulk optics and a full size Vidicon camera, renders the current lab prototype non-miniaturized (30–50 cm across); however, in the near future, miniaturized components (CCD camera) and spatial optimization will lead to a second prototype of drastically reduced dimensions (3–10 cm across). Using the current prototype, each image acquisition, digitization and post-processing, on average, requires less than a second. Generating an entire data set is highly dependent on the number of measurements and the selected delay between measurements, which can vary from a few seconds to a few minutes. Nonetheless, prototype optimization and the inclusion of a dedicated micro-controller responsible for challenge-response generation/acquisition, alongside a typical frame rate of 60fps can allow the generation of 60 high definition speckle patterns per second, thus enabling the generation of approximately 480000 binary sequences per second.

Our proposed PUF is being developed under the framework of the KONFIDO project. An overview of the KONFIDO project is presented in [8]. Other recent work regarding the KONFIDO project can be found in some recent papers. While in [9] the authors consider the ethical issues related to transborder data exchanges, user requirements are still being investigated while logging the transactions via blockchain is proposed in [10].

2 Experimental Results and Analysis

The first leg of the experimental procedure was performed by varying the wavelength of the laser by 100 pm, beginning at 1540 nm and reaching up to 1570 nm, and recording the corresponding speckle patterns produced by a single waveguide (constant random defects). The result of this process was the acquisition of 300 images, with a resolution of 340 × 340 pixels. The unpredictability of the system was assessed by calculating the magnitude of variation of these images. Moving forward, the resiliency of the system to noise was studied by keeping the waveguide and the illumination conditions constant, and acquiring multiple images (60) over a period of several minutes.

The Euclidean distances calculated between the standardized images of the two aforementioned datasets are presented in Fig. 2a. The left histogram of this graph represents the noise-induced dissimilarities between speckles obtained under identical experimental conditions, while the right one shows the discrepancies between images recorded by varying the wavelength of the incident beam. As can be seen, there is significant difference in the mean value of the two distributions (μnoise = 46.47 ± 9.8 and μwave = 380.47 ± 9.8) and clearly they do not overlap. This separation of distributions is a prerequisite for the proper and efficient operation of such systems during verification [1] in order to eliminate the possibility of two different illumination conditions (two different challenges) of the PUF to be falsely considered the same challenge, only affected by noise (false positive), or two different measurements under the same conditions to be falsely registered as different challenges (false negative).

Figure 2b shows the Hamming Distances of their corresponding hashed bit-strings (255 bit long) extracted via the Random Binary Hashing Method of [4]. The Random Binary Hashing Method can be summarized through the relation \( \bar{y} = sign\left[ {\left( {SFU} \right)y} \right] \), where \( y \) is the PUF response converted to a one-dimensional array of size N, \( \bar{y} \) is the resultant hashed bit-string of length M ≤ N, U is a diagonal random table (N × N), containing the values ±1 with Pr [Uii = 1] = Pr [Uii = −1] = 0.5, and F is the discrete Fourier table of (N × N) dimensions. S represents a matrix containing M entries randomly chosen from a uniform distribution (0, N), which are the indices of the elements being extracted to constitute the hashed bit-string. Finally \( sign \) is the quantization function, which is defined as:

As a preliminary analysis of the experimental setup, in order to find the necessary wavelength step, the laser wavelength was initially varied by 10 pm, starting at 1540 nm and reaching up to 1552 nm, still employing a single waveguide, albeit different to the one used prior. This process was repeated for different wavelength steps (i.e. 20, 30, 50, 60, 80 and 100 pm) and as a result, seven distinct sets of images with a resolution of 340 × 340 pixels were acquired.

Two representative histograms of Euclidean Distances, as calculated for the standardized images of the datasets acquired with 10 pm and 100 pm respectively, are presented in Fig. 3a. As can be seen, the distribution corresponding to the 10 pm measurements, compared to the 100 pm results, exhibits a pronounced tail, indicating an increased similarity between pictures and, subsequently, between the yet-to-be-calculated keys. This increased similarity is also verified via the cross-correlation coefficients (Fig. 3b) and can be attributed to a large number of excited modes being common throughout the challenges applied, due to the small wavelength variation used. In particular the cross-correlation coefficient for two consecutive images obtained with 10 pm and 100 pm wavelength difference was found to be 0.98 and 0.69 respectively. Therefore, the 100 pm wavelength step was selected, due to the fact that the cross-correlation coefficient for that step is low enough to provide sufficient differentiation between challenges.

It should be noted that, between the unpredictability measurements (Δλ = 100 pm) presented in the histograms of Figs. 2a and 3a, the specimen used was changed; therefore, the two distributions exhibit close but different mean values, due to the unique non-replicable defects used.

The unpredictability of the generated binary sequences is a critical performance metric, which evaluates the system’s resiliency to brute force attacks that aim in exploiting a statistical anomaly or bias of the generated code words. Under that light, a fundamental tool used by the cryptographic community is the NIST random number evaluation test suite. Using this suite of tests, the random sequence under consideration is being benchmarked against the statistical behavior of a known true random number source. The requirements of the NIST suite, regarding the length and number of the sequences, depend on the desired level of certainty (in our case α = 0.01) and are different for every test. For the level of certainty that was chosen in our case, the data set being tested should contain at least 1000 sequences, each 1Mbit in length.

So as to construct such a dataset, 30000 experimental images were utilized, each of which was processed through the Random Binary hashing method 30 distinct times. Each time, a unique matrix S was used for the selection of 1024 different pixels. The number of common pixels at the selection stage for all the matrices was chosen so as not to surpass 1 pixel per matrix. The extracted binary strings, of 1024 bit-length, from all images were then concatenated, in order to form a single matrix containing 1 Gbit of data. The outputs of the NIST tests are presented in Table 1.

The data sequences generated by our system, as illustrated in Table 1, have succeeded in the majority of the tests of the NIST suite (14/15 passed), only marginally failing to pass Maurer’s Universal test (proportion of success equal to 96.4%). However, that specific test is known to have generated false negatives on other, widely used, random sequences. Therefore, the proposed PUF can be considered as an adequate random number generator. Furthermore, the sequences which passed three of the tests which involve the percentages of 1 s and 0 s in the bit sequences, (100% of bit-strings passed the tests), failed at the uniformity test (P-value) nonetheless. The distribution of p-values for the frequency test is presented in Fig. 4b. These tests do not produce marginal results (low p-values), as can be seen in the results but, on the contrary, success rate is too high, which implies a highly balanced percentage of 1 s and 0 s in the bit sequences. The two histograms of Figs. 4b and c can be directly compared to each other, Fig. 4c being Maurer’s Universal test where the singular fail occurred. Nonetheless, this is a statistical anomaly which does not impose a security breach, due to the fact that an adversary has no indication regarding the probability of bit-flips. Furthermore, the fact that we re-hash images using unique pixel selection matrices with zero-pixel repetitions removes any potential experimental bias and forces the system to exhibit a “perfect” gaussian distribution. This feature, in turn, dictates a perfectly balanced number of logical ‘1’ and ‘0’ and potentially is the reason behind the anomaly in uniformity.

(a) Representation of the experimental bit-strings, black corresponds to “0” whereas white to logical “1”. No pattern can be visually identified. (b) P-Values distribution for the frequency test (NIST-success), (c) P-value distribution of the Maurer’s test (NIST-marginal fail). (d) Minimum conditional entropy distribution

In the quest to further fortify our claim to unpredictability, we recruit the help of the computation of the minimum conditional entropy (H-min), for all the pairs of bit-strings. The H-min is a typical conservative measure for unpredictability between pairs of code-words. In this case, we made use of the preexisting and aforementioned sample, which consisted of all challenges from a single PUF (Fig. 4a). It is evident that the mean value is exceptionally high (mean = 0.929), thereby confirming the suitability of a photonic PUF to be used as a cryptographic key generator. In Table 2, we include the minimum conditional entropy and the conditional entropy of various silicon-cast PUFs as well as those of a popular pseudo-random algorithm (Ziggurat), for comparative reasons. As is clearly illustrated, the proposed scheme offers comparable performance to both the Ziggurat algorithm as well as the best of what the silicon-cast PUFs have to offer, all the while vastly outperforming every other implementation.

The aforementioned results provide insight that the proposed PUF can operate as a random number generator without the vulnerabilities of typical approaches. On the other hand, these results are generated by exploiting different PUF instantiations, different challenges and by varying the pixel selection procedure (so as to generate 1 Gbps of data). This approach is not practical and demands the integration of a significant number of PUFs in the same device or the use of more sophisticated processing schemes. Nonetheless, the demonstrated sensitivity of the responses to the laser’s wavelength alongside the ability to simultaneously spatially modulate the incoming illumination can offer similar results in terms of performance without the cumbersome use of multiple PUFs.

Ultimately, it is important to note that the proposed system can generate bit-strings of any size which can be used as symmetric keys or as random seeds for an algorithmic pseudo-random generator with no additional processing. In the case of random number generation for asymmetric key encryption (private/public), where key requirements exist, like the PUF generated private key to be a large primary number, further operations can be performed during post-processing.

3 Conclusion

The proposed photonic PUF is based on an alternative scrambling mechanism compared to conventional approaches that is based on the random excitation and power distribution of a high number of transverse optical modes in a guiding medium. The proposed scheme allows the generation of binary sequences compatible with the NIST test, while at the same time offers higher performance compared to state of the art approaches in terms of Hamming- Euclidean distance and minimum conditional entropy. These results provide insight that further development of the proposed scheme could provide a secure standalone module for random number generation that does not share the vulnerabilities of pseudo-random algorithms or conventional PUFs and does not need secure nonvolatile storage. In near future implementations, the cumbersome tunable laser can be replaced with a spatial light modulator, thus allowing an exponentially larger challenge space (number of inputs), with similar or higher performance.

References

Pappu, R., Recht, B., Taylor, J., Gershenfeld, N.: Physical one-way functions. Science 297, 2026–2030 (2002)

Katzenbeisser, S., et al.: PUFs: Myth, fact or busted? A security evaluation of physically unclonable functions (pufs) cast in silicon. In: Prouff, E., Schaumont, P. (eds.) CHES 2012. LNCS, vol. 7428, pp. 283–301. Springer, Heidelberg (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-33027-8_17

Gao, Y., Ranasinghe, D.C., Al-Sarawi, S.F., Kavehei, O., Abbott, D.: Memristive crypto primitive for building highly secure physical unclonable functions. Sci. Rep. 5, 12785 (2015)

Armknecht, F., Maes, R., Sadeghi, A.R., Standaert, F.X., Wachsmann, C.: A formal foundation for the security features of physical functions. In: IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SSP), pp. 397–412. IEEE Computer Society (2011)

Shariati, S., Standaert, F., Jacques, L., Macq, B.: Analysis and experimental evaluation of image-based PUFs. J. Crypt. Eng. 2, 189–206 (2012)

Rührmair, U., Urban, S., Weiershäuser, A., Forster, B.: Revisiting optical physical unclonable functions. ePrint Archive, pp. 1–11 (2013)

Pain, H.J.: The Physics of Vibrations, vol. 570, 6th edn. Wiley, Hoboken (2005). https://doi.org/10.1002/0470016957

Staffa, M., et al.: KONFIDO: An OpenNCP-based secure eHealth data exchange system. In: Gelenbe, E., et al. (eds.) Euro-CYBERSEC 2018. CCIS, vol. 821, pp. 11–27. Springer, Cham (2018)

Faiella, G., et al.: Building an Ethical Framework for Cross-border applications: the KONFIDO project. In: Gelenbe, E., et al. (eds.) Euro-CYBERSEC 2018. CCIS, vol. 821, pp. 38–45. Springer, Cham (2018)

Castaldo, L., Cinque, V.: Blockchain-based logging for cross-border exchange of eHealth data in Europe. In: Gelenbe, E., et al. (eds.) Euro-CYBERSEC 2018. CCIS, vol. 821, pp. 46–56. Springer, Cham (2018)

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 727528 (KONFIDO—Secure and Trusted Paradigm for Interoperable eHealth Services). This paper reflects only the authors’ views and the Commission is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. Part of this work was implemented by scholarship from the IKY (State Scholarships Foundation) act “Reinforcement of research potential through doctoral research” funded by the Operational Programme “Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning”, 2014–2020, co-financed by the European Commission (European Social Fund) and Greek state funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

<SimplePara><Emphasis Type="Bold">Open Access</Emphasis> This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.</SimplePara> <SimplePara>The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.</SimplePara>

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

Akriotou, M., Mesaritakis, C., Grivas, E., Chaintoutis, C., Fragkos, A., Syvridis, D. (2018). Random Number Generation from a Secure Photonic Physical Unclonable Hardware Module. In: Gelenbe, E., et al. Security in Computer and Information Sciences. Euro-CYBERSEC 2018. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 821. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95189-8_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95189-8_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-95188-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-95189-8

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)