Abstract

The article takes up on the observations made by Kenesei (1994) the position of the Hungarian interrogative marker -e in the clause and its distribution across clause types. Specifically, there are three crucial points: (i) the marker -e is related to the CP-domain, where clause typing is encoded; (ii) -e is obligatory in embedded clauses and optional in main clauses; (iii) -e is licensed in finite clauses only. I argue that certain clause-typing properties are reflected in the Hungarian clause in a lower functional domain, FP. In particular, finiteness and the interrogative nature of the clause are encoded here, as also indicated by focussing in non-interrogative clauses and by constituent questions, respectively. The marker -e is base-generated in the F head, as opposed to a designated FocP or TP/IP, allowing it to fulfil its clause-typing functions. Base-generation is crucial (as opposed to lowering from C) since it is able to capture the relatedness between -e and finiteness: -e is specified as [fin] and while the FP may be generated to host focussed constituents (including wh-elements) in non-finite clauses, a lexically [fin] head cannot be inserted.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution.

Buying options

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Learn about institutional subscriptionsNotes

- 1.

For the sake of simplicity, I will refer to the relevant feature as [wh] both in constituent questions and in polar questions; for a possible differentiation between [wh] and [Q], see Bacskai-Atkari (2015).

- 2.

It has to be stressed that the parallelism between -e and if is indicative of both properties, that is, a head status and finiteness. Contrary to English if and French si ‘if’, Italian se ‘if’ can appear not only in finite but also in infinitival questions, as observed already by Kayne (1991). The difference is ultimately due to the elements occupying different positions. English if is a C head located high in the left periphery. By contrast, Italian se is located in a lower projection, identified as an IntP by Rizzi (1997), and the higher C containing the silent question operator in the specifier may or may not encode finiteness, as argued by Manzini (2012). The point is that Italian se is lexically specified as [wh] but not as [fin], unlike the C head if and the lower functional head -e.

- 3.

The examples in (6) are from the Old Hungarian Concordance corpus, and I retained the original spelling, while the examples in Kenesei (1994) use a normalised spelling. Kenesei (1994: 341, ex. 169) provides different examples for clause-initial ha ‘if’ and of the two examples in Kenesei (1994: 342, ex. 171) for clause-final -e in main clause interrogatives, the first one is identical to (6b), though my glosses and translation differ.

- 4.

Example (7a) is from the Historical Corpus of Private Correspondence (“Történeti Magánéleti Korpusz”).

- 5.

Similarly to the representation in (5), the verbal particle in (8a) does not stay in the VP but it moves up to a higher position, resulting in a “verbal particle + verb” order, which is surface-identical to the neutral word order found in sentences without an interrogative property or focussing (note that some movement to PredP/TP is still involved, see É. Kiss 2008, though not as high as to where the question particle is located). In (8b), the order is reversed, which clearly indicates that the verb has moved up; in this case, the verbal particle cannot move up because the wh-element occupies the relevant position. In Sect. 3, I will identify this projection as FP. The point is that the order of the verb and the verbal particle is indicative of verb movement only to the extent that the “reverse” order can be achieved only by the verb moving higher up, but the surface-neutral word order in itself does not say anything about the exact position of the verb.

- 6.

Naturally, this does not mean that the CP or the FP is freely iterable; I assume that the number of projections is as minimal as possible and iteration occurs when the inserted elements are lexically underspecified in terms of the features to be encoded, see Bacskai-Atkari (2018) for German. Further, the notion of iteration serves to indicate a differentiation from cartographic approaches, which also allow multiple CPs, see Rizzi (1997): the analysis proposed here does not assign pre-defined, designated functions to the individual CPs (or FPs).

- 7.

In this sense, the FP is an underspecified functional projection and it is not a designated projection either for finiteness or focus: the present approach does not seek to conflate a Rizzian FinP and a FocP but it is rather suggested that the projection is less specified than either of these two notions. In this respect the FP is similar to the CP as opposed to a specified ForceP for clause typing and FinP for finiteness; moreover, the CP can also host non-operator material as in focus fronting or German “formal movement” to the first position, see Fanselow (2004) and Frey (2005).

- 8.

Unlike the CP, the FP does not constitute a fully-fledged left periphery: whenever a [wh] feature is present, the FP is generated, and once the FP is generated in a finite clause, [fin] appears there, too; however, other clause-typing features are not associated with this domain (in other words, the FP is not automatically generated in all finite clauses). This presumably has historical reasons. As shown by É. Kiss (2014), the FP emerged to host the focussed element. Since wh-elements are inherently focussed, cf. É. Kiss (2002), they evidently landed in the same position in constituent questions: the FP is an optimal position for them because they can fulfill their role in terms of clause-type marking and they appear in a position where they can receive main stress. This pattern was reinterpreted as the FP being responsible for overtly marking [wh] and was hence extended to polar questions, see Bacskai-Atkari (2015). The same did not occur to other clause-typing features since they are not immediately related to the notion of focus. While the feature is present on both C and F, overt marking is restricted to the FP, due to reasons of economy. The [wh] on F is thus necessary for overt marking, while the [wh] on C is necessary because this makes relevant information to be available for matrix predicates selecting for an interrogative complement. Since the FP only inherits certain features from the CP, it does not have any specific features of its own but regarding [wh], this is the only projection in Modern Hungarian where the feature can actually be checked off. Naturally, the FP differs from the TP crucially in that the FP is related to clause typing and finiteness, whereby finiteness only specifies that the clause is tensed and thus a TP is generated, but the actual tense (present vs. past in Hungarian) is encoded by the TP. Further, the FP can appear in non-finite clauses, too, if it has no [fin] feature, see Sect. 4.

- 9.

Note that this is compatible with the present proposal that the FP is essentially underspecified: if the FP were tied to a focus interpretation, iteration would not be expected. Empirical data like (11) above, however, strongly suggest that the iteration of the projection should be allowed.

- 10.

The [fin] feature is essentially interpretable on the C head in Hungarian and does not always have to be lexicalised (lexicalisation is due to selectional restrictions imposed by the matrix predicate and/or the relative position of the subclause with respect to the matrix clause, but lexicalisation is not equivalent to feature checking). Further, the C head imposes selectional restrictions on the F head, if an FP is generated, and copying the [fin] feature ensures that no subclause contains a finite CP and a non-finite FP. However, the [fin] feature has to be checked off on the F head because it is uninterpretable on F. Note that I adopt a non-cartographic approach and hence there are no designated projections for every single feature, yet the multiple presence of a single feature on several heads does not imply multiple feature checking.

- 11.

I cannot discuss the mechanisms underlying focus movement here but I essentially adopt the view of Szendrői (2001) in that this movement operation is ultimately driven by stress, and hence there is no need to postulate a [focus] feature in syntax.

- 12.

The FP is iterated in this case to host the polarity markers (nem or the preverbal element); this is possible since by way of inserting -e into the lower F head, there is no active interrogative feature on that F head any more. As shown by Bacskai-Atkari (2015), the element nem was reanalysed from a Neg head into an F head in non-standard varieties, which analogically extended this possibility to preverbal elements that can function as polarity markers, too.

- 13.

The role of prosodic information cannot be examined here; see Prieto and Rigau (2007) for a similar view and an analysis for Catalan interrogatives.

- 14.

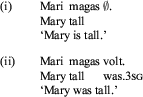

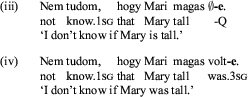

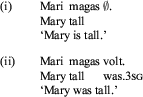

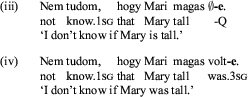

Note that while lexical verbs are always overt in non-elliptical clauses, the 3rd person present tense copula (either singular or plural) is zero in Hungarian, see Hegedűs (2013: 53–55). Observe:

It is reasonable to assume that adjectives, unlike verbs, do not take the subject argument on their own but they need a copula (see É. Kiss 2002: 71–74); Kádár 2011; Hegedűs 2013: 50–53). It follows that there is a zero copula in (i) fulfilling the same role as the overt past tense copula in (ii). In embedded polar interrogatives, -e attaches to the copula moving to F:

As can be seen in (iv), the copula immediately precedes -e, just like lexical verbs do. In (iii), the copula is zero and while -e syntactically adjoins the zero copula, it phonologically cliticises on the preceding adjective in PF, just like in elliptical constructions.

References

Bacskai-Atkari, Julia, and Éva Dékány. 2014. From non-finite to finite subordination: The history of embedded clauses. In The evolution of functional left peripheries in Hungarian syntax, ed. Katalin É. Kiss, 148–223. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bacskai-Atkari, Julia. 2015. A kérdő modalitás jelölése a beágyazott poláris kérdésekben és viszonya a funkcionális bal perifériák történetéhez. In Általános nyelvészeti tanulmányok XXVII: Diakrón mondattani kutatások, ed. Katalin É. Kiss. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Bacskai-Atkari, Julia. 2018. Deutsche Dialekte und ein anti-kartografischer Ansatz zur CP-Domäne. In Syntax aus Saarbrücker Sicht 2: Beiträge der SaRDiS-Tagung zur Dialektsyntax (Zeitschrift für Dialektologie und Linguistik Beihefte), ed. Augustin Speyer and Philipp Rauth, 9–29. Stuttgart: Steiner.

Belletti, Adriana. 2001. Inversion as focalization. In Subject inversion in Romance and the theory of Universal Grammar, ed. Aafke C. J. Hulk and Jean-Yves Pollock, 60–90. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Belletti, Adriana. 2004. Aspects of the low IP area. In The structure of CP and IP: The cartography of syntactic structures, vol. 2, ed. Luigi Rizzi Rizzi , 16–51. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bianchi, Valentina, and Silvio Cruschina. 2016. The derivation and interpretation of polar questions with a fronted focus. Lingua 170: 47–68.

Brody, Michael. 1990. Some remarks on the focus field in Hungarian. In UCL Working papers in linguistics, vol. 2, 201–225.

Brody, Michael. 1995. Focus and checking theory. In Approaches to Hungarian 5, ed. István Kenesei, 29–44. Szeged: JATE.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 2002. The syntax of Hungarian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 2008. Free word order, (non-)configurationality and phases. Linguistic Inquiry 39 (3): 441–474.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 2013. From Proto-Hungarian SOV to Old Hungarian Top Foc V X. Diachronica 30 (2): 202–231.

É. Kiss, Katalin. 2014. The evolution of functional left peripheries in the Hungarian sentence. In From head-final to head-initial: The evolution of functional left peripheries in Hungarian syntax, ed. Katalin É. Kiss, 9–55. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fanselow, Gisbert. 2004. Münchhausen-style head movement and the analysis of verb second. In Three papers on German verb movement, ed. Ralf Vogel, 9–49. Potsdam: Universitätsverlag Potsdam.

Frey, Werner. 2005. Zur Syntax der linken Peripherie im Deutschen. In Deutsche Syntax: Empirie und Theorie, ed. Franz Josef d’Avis, 147–171. Göteborg: Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

González i Planas, Francesc., 2014. On quotative recomplementation: Between pragmatics and morphosyntax. Lingua 146: 39–74.

Gyuris, Beáta. to appear. New perspectives on bias in polar questions: A study of Hungarian -e. International Review of Pragmatics. http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/18773109-00000003. Accessed 11 Dec 2016.

Hegedűs, Veronika. 2013. Non-verbal predicates and predicate movement in Hungarian. Utrecht: LOT.

Horvath, Julia. 1986. FOCUS in the theory of grammar and the syntax of Hungarian. Dordrecht: Foris.

Jayaseelan, Karattuparambil. 2001. IP-internal topic and focus phrases. Studia Linguistica 55 (1): 39–75.

Kádár, Edith. 2011. A kopula és a nominális mondatok a magyarban. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Kayne, Richard. 1991. Romance clitics, verb movement and PRO. Linguistic Inquiry 22 (4): 647–686.

Kenesei, István. 1994. Subordinate clauses. In The syntactic structure of Hungarian, ed. Ferenc Kiefer and Katalin É. Kiss, 275–354. San Diego: Academic Press.

Lipták, Anikó, and Malte Zimmermann. 2007. Indirect scope marking again: A case for generalized question formation. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 25(1): 103–155.

Manzini, Maria Rita. 2012. The status of complementizers in the left periphery. In Main clause phenomena: New horizons, ed. Lobke Aelbrecht, et al., 297–318. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Merchant, Jason. 2001. The syntax of silence: Sluicing, islands, and the theory of ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Poletto, Cecilia. 2006. Parallel phases: A study of the high and low left periphery of old Italian. In Phases of interpretation, ed. Mara Frascarelli, 261–294. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Prieto, Pilar, and Gemma Rigau. 2007. The syntax-prosody interface: Catalan interrogative sentences headed by que. Journal of Portuguese Linguistics 6 (2): 29–59.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Roberts, Ian. 2005. Principles and parameters in a VSO language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Szendrői, Kriszta. 2001. Focus and the syntax–phonology interface: University College London dissertation.

van Craenenbroeck, Jeroen van, and Anikó Lipták. 2008. On the interaction between verb movement and ellipsis: New evidence from Hungarian. In Proceedings of the 26th West Coast conference on formal linguistics, ed. Charles B. Chang and Hannah J. Haynie, 138–146. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the German Research Fund (DFG), as part of my project “The syntax of functional left peripheries and its relation to information structure” (BA 5201/1-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bacskai-Atkari, J. (2018). Marking Finiteness and Low Peripheries. In: Bartos, H., den Dikken, M., Bánréti, Z., Váradi, T. (eds) Boundaries Crossed, at the Interfaces of Morphosyntax, Phonology, Pragmatics and Semantics. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, vol 94. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90710-9_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90710-9_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-90709-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-90710-9

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)