Abstract

There are systematic parallels between the nominal and verbal domains of Hungarian in their inflectional paradigms. Seeking a descriptively and explanatorily adequate syntactic analysis of these morphological parallels, this paper presents an integrated approach to Hungarian possessive and definiteness marking, with clitics as the key players. The marker -JA (the ‘possessive morpheme’ in the noun phrase and the ‘definiteness agreement marker’ in present tense clauses) is traced back to an object clitic in Proto-Uralic, and analysed in the same terms in present-day Hungarian. The distribution of -JA across the nominal and present-tense verbal paradigms is derived from specific structural representations of person and the alienable/inalienable possession distinction; the absence of -JA from the past tense verbal paradigm is made to fall out from an analysis of Hungarian past tense forms as inalienably possessed inflected participles.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

Throughout this paper, I will represent the marker involved as -ja, with the capital ‘A’ being a cover for the harmonic value of the vowel (-a after back-vowel stems, -e after front vowel stems), and the capital ‘J’ as a cover for the glide -j and the vowel -i. The fact that, with front-vowel stems, -ja is pronounced -je in the nominal system and as -i in the verbal system has to do with the fact that, in possessives, there is always a vowel spelling out the relator head that mediates the predication relation between the possessor and the possessum—see Den Dikken (2015) for discussion.

- 2.

The fact that the past-tense forms show no high vowel or glide entails that the hypothesised object clitic -ja of present-day Hungarian is not tense-invariant. For Nevins (2011), tense invariance is a defining property of clitics. For Hungarian, however, the absence of tense invariance in the distribution of the clitic -ja is not an accidental gap: see Sect. 4 for an account of the Hungarian past tense that allows us to understand the absence of the -j from its paradigms.

- 3.

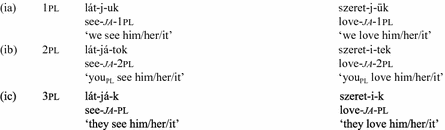

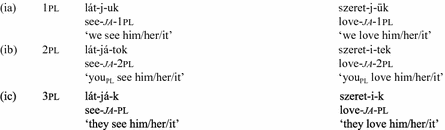

The constraint in (8) has carried over to Modern Hungarian only for the first and second person singular subject markers: the present tense plural forms -juk/jük in (ia) and -játok/itek in (ib) overtly contain the glide or high front vowel that represents the object clitic -ja, as do the forms -ják and -ik in (ic), for third person plural definite inflection.

This can be understood if the first and second person plural markers are not clitics. There is morphological support for this (along the lines of Preminger 2014). While first and second person singular -m and -d historically go back to the corresponding pronouns and still are transparently related to the first and second person singular pronouns, their plural counterparts in present-day Hungarian (first person -uk/ük and second person -tok/tek) show no synchronic surface relation to the corresponding nominative pronouns, mi and ti. (The second person plural forms do share a t—but the pronoun ti has the possessed plural marker -i, whereas the suffix -tok/tek has the default plural -k.) If they are not clitics but subject inflection markers, -uk/ük and -tok/tek do not seek to move from an argument position to the person head π (recall (11)). So no intervention effect arising from the presence of the object clitic -JA is expected in the first and second person plural. Only when the subject marker is a clitic (i.e., in the first and second person singular) is the marker -JA prevented from occurring, by the clitic co-occurrence restriction in (8), dating back to Proto-Uralic.

- 4.

The surface distribution -ja in possessive noun phrases is not just sensitive to the alienable/inalienable distinction. To a significant extent, the distribution of this marker is regulated by phonological considerations. The phonology can even cause -ja to occur in contexts in which the morphosyntax does not deliver it: inalienable possession constructions do include -ja whenever a phonotactic constraint forces it to occur. Following den Dikken (2015), the line that I take on this here is that the phonology co-opts an element that is available in the system, by analogical extension.

- 5.

The particular way in which den Dikken (2015) mobilises the structures in (16) to derive the distribution of the marker -ja in the Hungarian possessed noun phrase is unsuccessful in relating the marker -ja found in possessed noun phrases to the marker found in the definite agreement paradigm. It treats the -a of -ja as a relator, and the -j characteristic of alienable possession constructions as the exponent of the linker—a functional head outside the small clause (RP) in (16a) into whose specifier position the possessor raises in the course of the derivation, as shown in (i). With -a obligatorily raising to -j, and with the amalgamated marker -ja docking on to the possessum in the phonological component, the desired output for anyag-ja ‘his/her fabric (al.)’ and keret-je ‘his/her frame (al.)’ emerges.

- 6.

The fact that Hungarian says things like ‘we went to the movies with my wife’ in situations in which the speaker and his wife went to the movies together as a couple is compatible with this.

- 7.

Note that (19) allows for a simple descriptive generalisation regarding the distribution of the ‘special’ plural marker -i (as distinct from the ‘regular’ plural marker -k): -i occurs when the plural morpheme takes a relator phrase as its complement (i.e., in the associative plurals mi and ti, and in possessive plurals); -k occurs elsewhere. For the associative plural construction exemplified by János-ék ‘János and his entourage’, Dékány (2011:241–2) argues cogently that -ék is not the plural of the possessive anaphor -é ‘x’s one’ (which is -éi instead). A possible approach to -ék treats it as the concatenation of an unpossessed pronoun e and a local plural -k, with a silent relator linking the ék thus formed to János in an asyndetic coordination structure, analogous to the Afrikaans associative plural pa hulle ‘dad them’.

- 8.

In the verbal system of Modern Hungarian, the clitic co-occurrence restriction in (8) affects only the first and second person singular markers -m and -d: their plural counterparts co-occur with -ja, thanks to the fact that they are not clitics (recall fn. 3). But in the alienably possessed noun phrase, first and second person plural possessors resist -ja:

I pointed out in fn. 3 that the first and second person plural agreement markers in the definite verbal paradigm bear no morphological relationship with the corresponding personal pronouns. It was on this basis that I supported the conclusion that the first person plural marker in the definite verbal agreement paradigm of Modern Hungarian is not a clitic. It is probably significant in this connection that the marker for a first person plural possessor in Modern Hungarian (the -ünk of keretünk) does have a morphological connection with the pronoun: the nasal of the marker -ünk is historically identical with the nasal of the pronoun mi ‘we’. If we are to conclude on this basis (along the lines of Preminger 2014) that the marker -ünk is a plural-marked first person clitic, then the fact that it is incompatible with the clitic -JA will fall out along the lines of (17). Extending this line of thinking to the second person plural is not a straightforward matter, however: the -tek of keretetek ‘yourPL frame’ and the -tek of szeretitek ‘youPL love it’ look exactly the same; arguing for the clitic status of the former and the non-clitic status of the latter will therefore lack any transparent phonological support, and runs the risk of being a self-fulfilling prophecy.

- 9.

Except in the third person singular indefinite. Here exponence of the relator is probably suppressed in order to avoid syncretism between the definite and indefinite forms.

References

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2003. The syntax of ditransitives: Evidence from clitics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bartos, H. 1999. Morfoszintaxis és interpretáció. A magyar inflexiós jelenségek szintaktikai háttere [Morphosyntax and interpretation. The syntactic background of Hungarian inflexional phenomena]. PhD disseration, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary.

Benveniste, Emile. 1971. Problems in general linguistics. Coral Gables: University of Miami Press (originally appeared in French in 1966; Paris: Gallimard).

Bonet, Eulàlia. 1991. Morphology after syntax: Pronominal clitics in romance languages. PhD dissertation, MIT.

Coppock, Elizabeth, and Stephen Wechsler. 2012. The objective conjugation in Hungarian: Agreement without phi-features. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 30: 699–740.

Dékány, É. 2011. A profile of the Hungarian DP. The interaction of lexicalization, agreement and linearization with the functional sequence. PhD dissertation, University of Tromsø, Norway.

den Dikken, Marcel. 2006. Relators and linkers: The syntax of predication, predicate inversion, and copulas. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

den Dikken, Marcel. 2015. The morphosyntax of (in)alienably possessed noun phrases: The Hungarian contribution. In Approaches to Hungarian, vol. 14, ed. Katalin É. Kiss, Balázs Surányi and Éva Dékány, 121–45. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hajdú, Péter. 1972. The origins of Hungarian. In The Hungarian language, ed. Loránd Benkő, and Samu Imre, 15–48. The Hague: Mouton.

Nevins, Andrew. 2011. Multiple agree with clitics: Person complementarity vs. omnivorous number. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 29: 939–971.

Perlmutter, David. 1971. Deep and surface structure constraints in syntax. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Preminger, Omer. 2014. Agreement and its failures. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rezac, Milan. 2008. The syntax of eccentric agreement: The Person case constraint and absolutive displacement in Basque. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 26: 61–106.

Trommer, Jochen. 2003. Hungarian has no portmanteau agreement. In Approaches to Hungarian, vol. 9, ed. Péter Siptár, and Christopher Piñón, 283–302. Akadémiai Kiadó: Budapest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

den Dikken, M. (2018). An Integrated Perspective on Hungarian Nominal and Verbal Inflection. In: Bartos, H., den Dikken, M., Bánréti, Z., Váradi, T. (eds) Boundaries Crossed, at the Interfaces of Morphosyntax, Phonology, Pragmatics and Semantics. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, vol 94. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90710-9_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90710-9_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-90709-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-90710-9

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)