Abstract

The demand for dense matrix computation in large scale and complex simulations is increasing; however, the memory capacity of current computer system is insufficient for such simulations. Hierarchical matrix method (\(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices) is attracting attention as a computational method that can reduce the memory requirements of dense matrix computations. However, the computation of \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices is more complex than that of dense and sparse matrices; thus, accelerating the \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices is required. We focus on \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrix - vector multiplication (HMVM) on a single NVIDIA Tesla P100 GPU. We implement five GPU kernels and compare execution times among various processors (the Broadwell-EP, Skylake-SP, and Knights Landing) by OpenMP. The results show that, although an HMVM kernel can compute many small GEMV kernels, merging such kernels to a single GPU kernel was the most effective implementation. Moreover, the performance of BATCHED BLAS in the MAGMA library was comparable to that of the manually tuned GPU kernel.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The scale of computer simulations continues to increase as hardware capability advances from post-Peta to Exascale. At such scales, the asymptotic complexity of both computation and memory is a serious bottleneck if they are not (near) linear. In addition, the deep memory hierarchy and heterogeneity of such systems are a challenge for existing algorithms. A fundamental change in the underlying algorithms for scientific computing is required to facilitate exascale simulations, i.e., (near) linear scaling algorithms with high data locality and asynchronicity are required.

In scientific computing, the most common algorithmic components are linear algebra routines, e.g., matrix - vector multiplication, matrix-matrix multiplication, factorization, and eigenvalue problems. The performance of these components has been used as a proxy to measure the performance of large scale systems. Note that the general usefulness of the high performance LINPACK benchmark for supercomputers has long been disputed, and recent advancements of dense linear algebra methods with near linear complexity could be the final nail in the coffin.

Dense matrices requires \({\mathcal {O}}(N^2)\) storage and have a multiplication/factorization cost of \(\mathcal {O}(N^3)\). Hierarchical low-rank approximation methods, such as \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices [1], hierarchical semi-separable matrices [2], hierarchical off-diagonal low-rank matrices [3], and hierarchical interpolative factorization methods [4], reduce this storage requirement to \(\mathcal {O}(N \log N)\) and the multiplication/factorization cost to \(\mathcal {O}(N \log ^q N)\), where, q denotes a positive number. With such methods, there is no point performing large scale dense linear algebra operations directly. Note that, we refer to all hierarchical low-rank approximation methods as \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices in this paper for simplicity.

\(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices subdivide a dense matrix recursively, i.e., off-diagonal block division terminates at a coarse level, whereas diagonal blocks are divided until a constant block size obtained regardless of the problem size. Here, off-diagonal blocks are compressed using low-rank approximation, which is critical to achieving \(\mathcal {O}(N \log N)\) storage and \(\mathcal {O}(N \log ^q N)\) arithmetic complexity. Recently, \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices have attracted increasing attention; however, such efforts have a mathematical and algebraic focus. As a result, few parallel implementations of the \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrix code have been proposed.

In this paper, we focus on a parallel implementation. Specifically, we target matrix - vector multiplications on GPUs. Of the many scientific applications that involve solving large dense matrices, we selected electric field analysis based on boundary integral formulation. Our results demonstrate that orders of magnitude speedup can be obtained by merging many matrix - vector computations into a single GPU kernel and proper implementation of batched BLAS operations in the MAGMA library [5,6,7].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. An overview of the \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices and its basic computation are presented in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3, we focus on \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrix - vector multiplication (HMVM) and propose various single GPU implementations. Performance evaluation results are presented and discussed in Sect. 4, and conclusions and suggestions for future work are given in Sect. 5.

2 Hierarchical Matrix Method (\(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices)

\(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices are an approximation technique that can be applied to the dense matrices in boundary integral equations and kernel summation. The \(\mathcal {O}(N^2)\) storage requirement \(\mathcal {O}(N^3)\) factorization cost of \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices can be reduced to \(\mathcal {O}(N \log ^q N)\). Therefore, \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices allow calculations at scales that are otherwise impossible. In the following, we describe the formulation of \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices using boundary integral problems as an example.

2.1 Formulation of \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices for Boundary Integral Problems

Let H be a Hilbert space of functions in a \((d-1)\)-dimensional domain \(\varOmega \subset \) \(\mathbb {R} ^{d}\) and H’ be the dual space of H. For \(\textit{u} \in \textit{H}\), \(f \in {H'}\), and a kernel function of a convolution operator g: \(\mathbb {R}^{d} \times \varOmega \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\), we consider following the integral equation:

To calculate (1) numerically, we divide domain \(\varOmega \) into elements \(\varOmega ^{h} = \{\omega _{j} : j \in \textit{J}\}\), where \(\textit{J}\) is an index set. When we use weighted residual methods, the function u is approximated from a d-dimensional subspace \(\textit{H}^h \subset \textit{H}\). Given a basis \((\varphi _{i})_{\in \mathcal {I}}\) of \(\textit{H}^h\) for an index set \(\mathcal {I}:=\{1,...,N\}\), the approximant \(u^h \in \textit{H}^h\) to u can be expressed using a coefficient vector \(\phi = (\phi _i)_{i\in \mathcal {I}}\) that satisfies \(u^h = \sum _{i\in \mathcal {I}}^{}\phi _i\varphi _i\). Note that the supports of the basis \(\varOmega _{\varphi _i}^h := \mathrm{supp \ } \varphi _i\) are assembled from the sets \(\omega _j\). Equation (1) is reduced to the following system of linear equations.

Here, assume that we have two subsets (i.e., clusters) \(s,t\in \mathcal {I}\), where the corresponding domains are defined as follows:

A cluster pair (s, t) is ‘admissible’, if the Euclidian distance between \(\varOmega _s^h\) and \(\varOmega _t^h\) is sufficiently large compared to their diameters:

where \(\eta \) is a positive constant number depending on the kernel function g and the division \(\varOmega ^h\). For the domain corresponding to the admissible cluster pairs \(x \in \varOmega _s^h\), \(y \in \varOmega _t^h\), we assume that the kernel function can be approximated at certain accuracy using a degenerate kernel such as

where k is a positive number. Such kernel functions are employed in various scientific applications, e.g., electric field analysis, mechanical analysis, and earthquake cycle simulations. The kernel functions in such applications can be written as follows:

When we consider static electric field analysis as a practical example, the kernel function is given by

Here, \(\epsilon \) denotes the electric permittivity. Figure 1 shows the calculation result when a surface charge method is used to calculate the electrical charge on the surface of the conductors. We divided the surface of the conductor into triangular elements and used step functions as the base function \(\varphi _i\) of the BEM.

An \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrix \(\tilde{A}_\mathcal {H}^K\), the approximation of A in (2), is characterized by a partition \(\mathcal {H}\) of \(\textit{N} \times \textit{N}\) with blocks \(h=s_h \times t_h \in \mathcal {H}\) and block-wise rank K (Fig. 2). Note that most off-diagonal blocks in \(\tilde{A}_\mathcal {H}^K\) have a low-rank, and the diagonal blocks remain dense. A low-rank matrix \(\tilde{A}_\mathcal {H}^K|^h\), which approximates a sub-matrix \(A_\mathcal {H}|^h\) of the original matrix corresponding to block h, is expressed as

where \(v^\nu \in \mathbb {R}^{s_h}\), \(w^\nu \in \mathbb {R}^{t_h}\), and \(k_h \le K\). Typically, the upper limit K of the ranks of sub-matrices is set such that \(||A-\tilde{A}_\mathcal {H}^K||_\mathcal {F} \le \epsilon \) for a given tolerance \(\epsilon \).

For \(x, b \in \mathbb {R}^\mathcal {I}\), we consider the following equation:

To solve (9), we use a Krylov subspace method, such as the BiCGSTAB method. The HACApK library [8] and ppOpen-APPL/BEM [9, 10] implement these computations in parallel and distributed computer environments using the MPI and OpenMP.

Partition structure of \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrix \(\tilde{A}_\mathcal {H}^K\) for the two-sphere model in Fig. 1. Dark and light red blocks represent dense sub-matrices and low-rank sub-matrices, respectively. (Color figure online)

2.2 BiCGSTAB Method for the Hierarchical Matrix

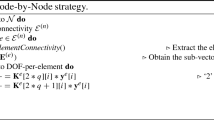

We select BiCGSTAB method to solve (2) because the coefficient matrices are not positive definite. Similar to the BiCGSTAB method for a dense matrix, most of the execution time of the BiCGSTAB method for an \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrix is spent in HMVM. Low-rank sub-matrix - vector multiplication involves two dense matrix - vector multiplications; therefore, HMVM results in many dense matrix - vector multiplications (Fig. 3). Figure 4 shows the pseudo code of the HMVM kernel in ppOpen-APPL/BEM which is optimized for multi-core CPUs. The original code was implemented in Fortran; however, to develop a GPU version of HMVM, we have developed a C version that is nearly the same as the algorithm in the original code. Hereafter, we refer to this kernel as the OMP kernel.

HMVM comprises many low-rank sub-matrix - vector multiplications for off-diagonal blocks and dense sub-matrix - vector multiplications for diagonal blocks. These matrix - vector calculations correspond to the leaves of a tree structure; thus, we refer to both low-rank sub-matrix - vector multiplication and dense sub-matrix - vector multiplication as leaves. This parallel implementation requires atomic addition because multiple leaves may have partial values of the same index of the result vector. Although it can be eliminated using atomic operations in each matrix - vector multiplications, the OMP kernel merges partial results after sub-matrix - vector multiplication because atomic operations in sub-matrix - vector multiplication incur additional computation cost and cannot obtain better performance than previous implementations. Note that the length of the parallel loop is sufficient for current parallel processors because our target matrices have greater than thousands of leaves.

3 \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrix Computation on GPU

The BiCGSTAB method employs basic matrix and vector operations. Here, HMVM is a dominant component in terms of the time to solution. Therefore, we consider a GPU implementation of HMVM on an NVIDIA Tesla P100 (Pascal architecture) GPU [11].

3.1 BLAS GEMV

As discussed in Sect. 2, HMVM consists of many dense sub-matrix - vector multiplications. A dense matrix - vector multiplication can be replaced by the well-known general matrix vector product calculation (GEMV) in BLAS, and this calculation is provided by some BLAS libraries for NVIDIA GPUs, e.g., the CUBLAS [12] and MAGMA libraries. Therefore, using these BLAS libraries, we can implement HMVM relatively easily. Here, we use CUBLAS for GPUs. In addition, to compare performance, we also implement HMVM using the Math Kernel Library (MKL) for CPUs. Hereafter, we refer to these kernels as the CUBLAS and MKL kernels. Figures 5 and 6 show the pseudo code of an HMVM kernel using the CUBLAS and MKL kernels, respectively.

3.2 Simple GEMV Kernels

BLAS libraries are useful; however, they cannot always achieve optimal performance. Generally, such libraries perform optimally for large matrix calculations. In contrast, HMVM involves many small GEMV calculations. With GPUs, if the CUBLAS GEMV function is used in HMVM, performance will be low because of the lack of parallelism. Moreover, launching GPU kernels requires significant time. In addition, the CUBLAS kernel launches a GEMV kernel for each leaf; thus, the incurred overhead will increase execution time.

To evaluate and reduce this overhead, we implemented two HMVM kernels using CUDA.

The first is a GEMV kernel that performs a single GEMV calculation using the entire GPU, and each thread block calculates one GEMV row. Threads in the thread block multiply the matrix and vector elements and calculate the total value using a reduction operation. The reduction algorithm is based on an optimized example code in the CUDA toolkit, which we refer to as the SIMPLE kernel. Figure 7 shows the pseudo code of an HMVM kernel using the SIMPLE kernel. The execution form (i.e., the number of thread block and threads per block) is an optimization parameter.

Note that many of the GEMV calculations in the HMVM are small; thus, it is difficult for the SIMPLE kernel to obtain sufficient performance. To improve performance, some parts of the GPU should calculate a single GEMV in parallel. Thus, we developed an advanced kernel in which a single GEMV kernel is calculated by one thread block, and each line in a single GEMV is calculated by a single warp. Moreover, to eliminate data transfer between the CPU and GPU, two GEMV calculations in low-rank sub-matrix - vector multiplication are merged to a single GPU kernel, and shared memory is used rather than global memory. Note that we refer to this kernel as the ASYNC kernel. Figure 8 shows the pseudo code of an HMVM kernel with the ASYNC kernel. Here, the execution form is also an optimization parameter, similar to the SIMPLE kernel; however, the number of thread blocks is always one and multiple GPU kernels are launched concurrently using CUDA stream. Moreover, atomic function is used to merge the partial results because the atomic addition operation of the P100 is fast enough and this implementation can make memory management easy.

Pseudo code of the HMVM kernel with CUDA (ASYNC kernel); one thread block calculates one GEMV, each warp in the thread blocks calculates a single line, two GEMV calculations of low-rank sub-matrix - vector multiplication are merged into a single GPU kernel, and multiple GPU kernels are launched asynchronously.

3.3 All-in-One Kernel

It is well known that launching a GPU kernel requires much more time than launching a function executed on a CPU. In previous HMVM kernels, the number of launched GPU kernels has depended on the number of leaves; therefore, GPU kernels are launched many times, which may degrade performance. To address this issue, we have created a new GPU kernel that calculates all sub-matrix - vector multiplications using a single GPU kernel, which we refer to as the A1 kernel.

Figure 9 shows the pseudo code of an HMVM kernel with the A1 kernel. In this kernel, each leaf is calculated by a single warp, and the basic algorithm of each leaf is similar to that of the ASYNC kernel. Although the loop for the number of leaves is executed on the CPU in the ASYNC kernel, this loop is executed on the GPU in the A1 kernel. Similar to the ASYNC kernel, here, the execution form is an optimization parameter.

3.4 BATCHED BLAS

Similar to HMVM, many small BLAS calculations are required in various applications, such as machine learning, graph analysis, and multi-physics. To accelerate many small BLAS calculations, batched BLAS has been proposed by several BLAS library developers. For example, MKL, MAGMA, and CUBLAS provide batched BLAS functions. Although gemm is the main target function of batched BLAS, MAGMA provides batched gemv functions for a GPU [13]. Figure 10 shows one of the interfaces of the batched gemv function in MAGMA.

Note that we implemented an HMVM kernel using the batched gemv function of MAGMA [14]. Figure 11 shows the pseudo code of our HMVM kernel with BATCHED MAGMA BLAS, which we refer to as the BATCHED kernel. In this kernel, the calculation information is constructed in the loop of leaves on the CPU, and the GPU calculates the entire HMVM calculation using the magmablas_dgemv_vbatched_atomic function. Note that the magmablas_dgemv_vbatched_atomic function is not the original BATCHED MAGMA function, i.e., it is a function that we modified to use atomic addition to produce the results.

4 Performance Evaluation

4.1 Execution Environment

In this section, we discuss the performance obtained on the Reedbush-H supercomputer system at the Information Technology Center, The University of Tokyo [15]. Here, we used the Intel compiler 16.0.4.258 and CUDA 8.0.44. We used the following main compiler options: -qopenmp -O3 -xCORE-AVX2 -mkl=sequential for the Intel compiler (icc and ifort) and -O3 -gencode arch=compute_60, code="sm_60,compute_60" for CUDA (nvcc). The MKL kernel is called at the multi-threaded region; thus, sequential MKL is linked. Note that threaded MKL obtained near by the same performance in all cases. Here, we used MAGMA BLAS 2.2.

Moreover, to compare performance with other current processors, we measured the performance on a Skylake-SP CPU and a Knights Landing processor. The Skylake-SP processor is installed in the ITO supercomputer system (test operation) at Kyushu University [16], and Intel compiler 17.0.4 with -qopenmp -O3 -xCORE-AVX512 -mkl=sequential compiler options was used. The Knights Landing processor is installed in the Oakforest-PACS at JCAHPC [17] and Intel compiler 17.0.4 with -qopenmp -O3 -xMIC-AVX512 -mkl=sequential compiler options was used.

Table 1 shows the hardware specifications of all target hardware. Note that we focus on the performance of a single socket in this paper. The execution times of the Broadwell-EP (BDW) and Skylake-SP (SKX) were measured using all 18 CPU cores. The cluster mode of Knights Landing (KNL) was the quadrant mode, and the memory mode was flat (i.e., only MCDRAM was used). Note that the KNL execution times were measured using 64 threads with scatter affinity and hyper-threading degrades performance.

4.2 Target Data

The four matrices in Table 2 are the target matrices of this evaluation. These matrices were generated from electric field analysis problems. Here, the 10ts and 100ts matrices were generated from a problem with a single spherical object, and the 216h matrix was generated from a problem with two spherical objects. In addition, a human_1x1 matrix was generated from a problem with a single human-shaped object.

The sizes of the low-rank sub-matrices and small dense sub-matrix of each target matrix are shown in Fig. 12, where the two left graphs of each matrix show the size of the low-rank sub-matrices and the right shows the size of the small dense sub-matrix.

With the 10ts and 100ts matrices, the size of the approximate matrices ndt and ndl was less than approximately 200 (some were close to 700). Note that all ranks kt were very small (the largest was 23). With the small dense matrices, all matrix lengths were less than 100, and many were less than 30.

With the 216h and human_1x1 matrices, the aspect ratio of the small dense matrices was similar to that of the 10ts and 100ts matrices. With the approximate matrices, although kt was greater than that of the 10ts and 100ts matrices, the aspect ratio was similar. However, although nearly all ndt and ndl lengths were less than 1000, a few matrices had ndt and ndl lengths that were greater than 5000.

Note that the sizes of these matrices depend on the target matrix. Moreover, the size is controlled by the matrix assembling algorithm and HACApK parameters. The above sizes were generated using current usual HACApK parameter settings. It is expected that optimizing the matrix size will affect HMVM performance, and this will be the focus of future work.

4.3 Performance Evaluation

In this subsection, we discuss execution time and performance. Note that the dominant part of the BiCGSTAB method is HMVM; therefore we focus on the execution time of the HMVM. Moreover, the BiCGSTAB method does not modify the matrix data in its own kernel; thus, the each execution time does not include the time required to perform data transfer between the main memory and the GPU in the main iteration of the BiCGSTAB method. Figures 13 and 14 show the execution times for the target matrices. All times are the average execution time of 100 HMVM calculations in 50 BiCGSTAB iterations. As mentioned in the previous section, although the execution form (i.e., grid layout) of the SIMPLE, ASYNC, and A1 kernels are the optimization parameters, only the fastest cases are shown and the chosen forms are shown at Table 3. Note that the ASYNC kernel launches many GEMV kernels asynchronously with a single thread block. The “#leaves” grids of the A1 kernel indicate that the number of thread blocks is equal to the number of leaves, and the outermost GPU kernel loop is eliminated.

Figure 13(a) shows the execution times of all measurements on the Reedbush-H. As can be seen, the CUBLAS, SIMPLE, and ASYNC kernels were too slow for a performance comparison with the fast kernels. Figure 13(b) shows graphs with a limited Y-axis from Fig. 13(a). Relative to the CPU execution time, the OMP and MKL kernels obtained nearly the same performance with all target matrices. Focusing on the GPU execution time, it is clear that the execution times of the CUBLAS, SIMPLE, and ASYNC kernels were much greater than that of the A1 and BATCHED kernels. The major difference between these two groups is the number of launched GPU kernels. As mentioned in the previous section, launching GPU kernels requires more time than executing functions on the CPU and causes long execution times with the three slower kernels. Therefore, although the ASYNC kernel improves the performance compared to the CUBLAS and SIMPLE kernels, its performance is much slower than that of the A1 and BATCHED kernels. On the other hand, the A1 and BATCHED kernels obtained much higher performance than the other kernels. Note that the A1 kernel showed better performance than the BATCHED kernel because the batched functions in MAGMA BLAS include computations that are unnecessary for HMVM calculation or the execution form is unoptimized.

The execution time ratio of the OMP kernel (BDW) to the A1 kernel was 17.37% with the 10ts matrix, 24.22% with the 216h matrix, 18.18% with the human_1x1 matrix, and 14.45% with the 100ts matrix, and the execution time ratio of the OMP kernel (BDW) to the BATCHED kernel was 34.39% with the 10ts matrix, 32.07% with the 216h matrix, 31.43% with the human_1x1 matrix, and 21.67% with the 100ts matrix. Considering that the calculation performance ratio of the GPU to CPU was 11.4% and the memory performance was 10.5%, there might be room to improve the GPU implementation.

Figure 14 shows the execution times of the A1 kernel, BATCHED kernel, and CPU (i.e., the OMP and MKL kernels) on the Broadwell-EP (BDW), Skylake-SP (SKX), and Knights Landing (KNL). All times of the KNL are the average execution time of 100 HMVM calculations in 50 BiCGSTAB iterations, but that of the SKX are average execution time of greater than 10 iterations because of the resource limitation of the test operation.

Relative to the performance of SKX, both the OMP and MKL kernels required nearly 30% less execution time than the OMP kernel of the BDW. By considering the performance gap between the BDW and SKX in terms of specification, i.e., the SKX has 45% greater memory bandwidth and more than 200% greater calculation performance than the BDW, it was expected that the SKX would obtain higher performance than 30%. However, HMVM calculation involves various loop length, and it is not a suitable calculation for AVX512; therefore, the obtained performance is not unexpected. On the other hand, there are large differences between the OMP kernel and MKL kernel of the KNL. However, it is difficult to describe the reason why the performance of the MKL kernel was unstable because the MKL implementation is undisclosed. There might be room to improve the KNL implementation. By considering the performance gap between the BDW and KNL in terms of specification, i.e., the KNL has 7.6 times greater memory bandwidth and 5.0 times greater calculation performance than the BDW. The OMP kernel of the KNL obtained 34% to 57% better performance than the OMP kernel of the BDW. Similar to the SKX, the KNL has much higher peak performance than the BDW; thus the performance improvement of the KNL is insufficient relative to the performance gap between the BDW and KNL.

Figure 15 shows the entire execution time of the BiCGSTAB method in all target environments. Here, although the iteration count was not exactly the same, only the total computation times are compared. Nearly all vector and matrix calculations of the BiCGSTAB method were executed on the GPU with the A1 kernel. Similarly, nearly all vector and matrix calculations of the BiCGSTAB method were executed on the GPU using MAGMA BLAS with the BATCHED kernel. To simplify the evaluation, only the shortest times of the OMP and MKL kernels for each hardware configuration are shown. The execution times of the A1 and BATCHED kernels were less than that of the other processors, and the A1 kernel demonstrated the fastest performance with all target matrices. Note that the SKX was faster than the BDW for all matrices and was faster than the KNL with the 10ts, 216h, and human_1x1 matrices. However, the KNL showed a shorter execution time than the BDW and SKX with the 100ts matrix. The reason for this may be that the 100ts matrix has a greater number of large sub-matrices than the other matrices. Note that the larger target matrix, the greater performance KNL obtained relatively.

5 Conclusion

Using \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices is an essential technique to solve large and complex computer simulations using a small amount of memory. In this paper, we focus on the BiCGSTAB method with \(\mathcal {H}\)-matrices for electric analysis problems on GPUs. Since matrix - vector multiplication is a dominant part of the execution time of the BiCGSTAB method, we primarily focused on the performance and implementation of HMVM. We implemented five GPU kernel variations and compared the execution times of several CPUs and a manycore processor. The results indicate that, because HMVM requires many small GEMV computations and launching GPU kernels requires a long time, merging the computation of GEMV kernels into a single kernel (i.e., the A1 kernel) was the most effective implementation. This implementation obtained much better performance among the compared processors. Moreover, the BATCHED BLAS function of MAGMA, which executes many BLAS computations using a single GPU kernel (BATCHED kernel), obtained good performance. Although the performance of the BATCHED kernel was less than that of the A1 kernel with all matrices, developing the A1 kernel requires much more time and labor than the BATCHED kernel. Therefore, it would be beneficial to implement an A1 kernel-based HMVM library in HACApK. In the best case, the execution time ratio of the OMP kernel on the Broadwell-EP to the A1 kernel was 14.45% with the 100ts matrix. Owing to the higher HMVM performance, the BiCGSTAB method with A1 kernel demonstrated overall better performance than the other kernels on the GPU (i.e., the NVIDIA Tesla P100), as well as the Skylake-SP and Knights Landing hardware.

Note that various opportunities for future work remain. For example, we are currently implementing and evaluating in the multi-GPU and multi-nodes environments. In such environments, load balancing and data transfer optimization are very important, and to accelerate data transfer between GPUs, the data layout in GPU memory may have a significant impact on performance. Simplification of partition structure of H-matrices used in lattice H-matrices would be required to improve load balancing and communication pattern [18]. Currently, it is uncertain whether the A1 and BATCHED kernels have good data layouts. The data layouts of approximate and small dense matrices can be modified by configuring the parameters of the matrix assembly process in the HACApK library. The relationship between the data layout of matrices and performance is an interesting topic. Moreover, optimization of the execution forms of GPU kernel in A1 kernel to various target matrices is an important issue; thus, evaluating the performance of various matrices is required. In addition, we are considering providing an implementation of our HMVM kernel in HACApK.

References

Hackbusch, W.: A sparse matrix arithmetic based on H-Matrices, Part I: introduction to h-matrices. Computing 62, 89–108 (1999)

Chandrasekaran, S., Dewilde, P., Gu, M., Lyons, W., Pals, T.: A fast solver for HSS representations via sparse matrices. SIAM J. Matrix Anal. Appl. 29(1), 67–81 (2006)

Ambikasaran, S.: Fast Algorithms for Dense Numerical Linear Algebra and Applications. Ph.D thesis, Stanford University (2013)

Ho, K.L., Ying, L.: Hierarchical interpolative factorization for elliptic operators: differential equations. Commun. Pure Appl. Math. 69(8), 1415–1451 (2016)

MAGMA: MAGMA (2017). http://icl.cs.utk.edu/magma/. Accessed 11 Aug 2017

Dongarra, J., Duff, I., Gates, M., Haidar, A., Hammarling, S., Higham, N.J., Hogg, J., Lara, P.V., Zounon, M., Relton, S.D., Tomov, S.: A Proposed API for Batched Basic Linear Algebra Subprograms. Draft Report, May 2016 (2016)

Batched BLAS: Batched BLAS (2017). http://icl.utk.edu/bblas/. Accessed 23 Dec 2017

Ida, A., Iwashita, T., Mifune, T., Takahashi, Y.: Parallel hierarchical matrices with adaptive cross approximation on symmetric multiprocessing clusters. J. Inf. Process. 22(4), 642–650 (2014)

Iwashita, T., Ida, A., Mifune, T., Takahashi, Y.: Software framework for parallel BEM analyses with H-matrices using MPI and OpenMP. Procedia Comput. Sci. 108, 2200–2209 (2017). International Conference on Computational Science, ICCS 2017, Zurich, Switzerland, 12–14 June 2017

ppOpen-HPC: Open Source Infrastructure for Development and Execution of Large-Scale Scientific Applications on Post-Peta-Scale Supercomputers with Automatic Tuning (AT) (2017). http://ppopenhpc.cc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/ppopenhpc/. Accessed 11 Aug 2017

NVIDIA: Tesla P100 Most Advanced Data Center Accelerator (2017). http://www.nvidia.com/object/tesla-p100.html. Accessed 11 Aug 2017

NVIDIA: cuBLAS: CUDA Toolkit Documentation (2017). http://docs.nvidia.com/cuda/cublas/. Accessed 11 Aug 2017

Dong, T., Haidar, A., Tomov, S., Dongarra, J.: Optimizing the SVD bidiagonalization process for a batch of small matrices. Procedia Comput. Sci. 108, 1008–1018 (2017). International Conference on Computational Science, ICCS 2017, Zurich, Switzerland, 12–14 June 2017

Yamazaki, I., Abdelfattah, A., Ida, A., Ohshima, S., Tomov, S., Yokota, R., Dongarra, J.: Analyzing Performance of BiCGStab with Hierarchical Matrix on GPU cluster. In: 2018 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS) (2018, in press)

Information Technology Center, The University of Tokyo: Reedbush Supercomputer System (2017). http://www.cc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/system/reedbush/index-e.html. Accessed 08 Aug 2017

Research Institute for Information Technology, Kyushu University: Supercomputer system ITO (2018). https://www.cc.kyushu-u.ac.jp/scp/system/ITO/. Accessed 09 Feb 2018 (in Japanese)

JCAHPC (Joint Center for Advanced HPC): Oakforest-PACS (2018). http://jcahpc.jp/eng/ofp_intro.html. Accessed 09 Feb 2018

Ida, A.: Lattice H-matrices on distributed-memory systems. In: 2018 IEEE International Parallel and Distributed Processing Symposium (IPDPS) (2018, in press)

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 17H01749, JST/CREST, German Priority Programme 1648 Software for Exascale Computing (SPPEXA-II), and “Joint Usage/Research Center for Interdisciplinary Large-scale Information Infrastructures” and “High Performance Computing Infrastructure” in Japan (Project ID: jh160041). Computations were primarily performed using the computer facilities at the Information Technology Center, The University of Tokyo (Reedbush), the Research Institute for Information Technology, Kyushu University (ITO), and JCAHPC (Oakforest-PACS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

Ohshima, S., Yamazaki, I., Ida, A., Yokota, R. (2018). Optimization of Hierarchical Matrix Computation on GPU. In: Yokota, R., Wu, W. (eds) Supercomputing Frontiers. SCFA 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10776. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69953-0_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69953-0_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-69952-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-69953-0

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)