Abstract

We review a recent literature that shows that interactions between markets, created by the market entry and exit behavior of boundedly rational firms, may cause complex endogenous dynamics. In particular, these models predict that welfare decreases if firms rapidly switch between markets. Against this background, we show that policy makers have the opportunity to stabilize markets and thus to enhance welfare by regulating interacting markets. For instance, imposing profit taxes reduces the markets’ profit differentials and thus slows down the firms’ market entry and exit behavior. However, these stabilization policies may also lead to undesirable side effects, such as coexistence of attractors, hysteresis effects and, in a multi-region setting, failure of policy makers to coordinate on the globally optimal policy. Moreover, regulation may be subject to the lobbying efforts of special interest groups and thus not be optimal.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

JEL classification

1 Introduction and Outline

In the wake of the financial crisis that hit the global economy by the end of the noughties many economists and policy makers realized that the strong links between individual markets played an important role in allowing the crisis to spread globally, or may even have been at the core of the emergence of the crisis (see, amongst others, Karras and Song 1996, Bordo et al. 2001 and Shiller 2015). This has spawned a literature that deals both with the effect that interactions between markets have on market stability, and with the policy measures that may be implemented to counter the instabilities that potentially arise from these interactions. While some policy measures indeed stabilize markets and thereby improve welfare, other policy measures may yield surprising and unwanted side effects. In this chapter we will review a small part of that literature.

That individual markets may lead to instability has been recognized for some time already. Classic textbook examples are the cobweb model under naïve expectations (see Ezekiel 1938) or the Cournot oligopoly model under best reply dynamics (see Theocharis 1959). More recently the development of the theory of nonlinear dynamical systems has led to an increased attention for the possibility of market instability. Some early and important applications of this theory are Grandmont (1985) and Bullard (1994) on overlapping generations models, Chiarella (1988), Hommes (1994) and Brock and Hommes (1997) on cobweb markets, Day and Huang (1990), Lux (1995) and Brock and Hommes (1998) on financial markets and Puu (1991) and Kopel (1996) on Cournot duopoly models. Laboratory experiments with paid human subjects suggest that instability is indeed likely to occur in some of these market environments (see e.g. Hommes et al. 2005 and Heemeijer et al. 2009).

In the last decade the interaction between markets has been identified as an additional route to market instability. Dieci and Westerhoff (2009, 2010), for example, find that two stable cobweb markets may become unstable when they are linked. Tuinstra et al. (2014) show that this increased instability may result in the counterintuitive policy prescription that under certain circumstances strictly positive import tariffs are welfare enhancing. Even in the absence of naïve price expectations and cobweb dynamics, linking two markets may lead to instability, as demonstrated by Schmitt et al. (2017a, b). If firms are sufficiently sensitive to profit differences between markets this may lead to unstable dynamics. Following the insights from Schmitt and Westerhoff (2015, 2017), the papers by Schmitt et al. (2017a, b) investigate how the introduction of profit taxes may dampen the profit differences between the two markets and thereby stabilize the dynamics and increase welfare. However, these profit taxes may also induce undesirable side effects, such as coexistence of attractors and hysteresis effects (Schmitt et al. 2017a), or it may turn out to be difficult for regulators to coordinate on a globally optimal profit tax policy (Schmitt et al. 2017b).

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 we provide a brief review of the literature on market interactions, and Sect. 3 discusses some contributions that analyze the stabilizing or destabilizing effect that regulatory policies may have on the dynamics of interacting markets. Section 4 concludes.

2 Market Interactions

The benefits of a non-regulated market economy depend crucially on the assumption that markets are stable and prices attain their equilibrium values. In this way a (Pareto) efficient allocation of scarce resources will be established, and governments have no reason to interfere in the market process (other than for, typically subjective, distributional concerns). Market stability therefore has been, and continues to be, an important field of research in economics. One of the simplest and intuitive models to study this issue is by means of the so-called cobweb model, initially introduced by Ezekiel (1938). This model represents a market where suppliers face a production lag. That is, it takes one period for their (non-storable) product to be produced, implying that the producers have to make a supply decision one period in advance – this setting is relevant, for example, for many agricultural markets. The optimal supply decision consequently depends upon the producers’ expectation of the market clearing price in the next period. The actual market price is the price that clears the market, that is, the price that equates consumer demand for the produced commodity with the aggregate supply that was determined, on the basis of producers’ price expectations, in the previous period. If the number of producers on the market and the consumer demand schedule for the produced commodity is constant over time this gives rise to a unique ‘fundamental’ steady state price. If the producers have rational expectations (that is: they know the full market structure, including consumer demand and cost functions of all producers), and if in addition there is common knowledge of rationality (that is: every producer knows that every producer is rational, and knows that every producer knows that every producer is rational, and so on) they will coordinate on this fundamental steady state price (and correctly predict it).

However, these assumptions are very strong, and less demanding forms of expectation formation have been suggested in the literature. In particular, at the other extreme we can find naïve expectations, as discussed in the original model of Ezekiel (1938), where producers predict next period’s price to be equal to the last observed price (that is, the price in this period). Introducing naïve expectations for all producers implies that prices evolve according to a first order difference equation which, depending on the relative slopes of the consumer demand and producer supply functions, as well as on the number of producers, may lead to oscillating converge to the unique steady state, to diverging oscillations, or to a period two cycle, where market clearing prices jump back and forth between a low and a high level.

More complicated unstable dynamics may emerge in the cobweb model for more sophisticated, but still boundedly rational, prediction strategies. For example, Chiarella (1988) and Hommes (1994, 1998) consider adaptive expectations, where the price expectation is adapted in the direction of the last observed price. They show that this expectation mechanism can lead to more erratic dynamics in prices and predictions. Another promising avenue to study the role of expectations in the stability of the cobweb market was advanced by the influential work of Brock and Hommes (1997). They assume that producers in the cobweb model form expectations either in a rational or in a naïve manner, and switch between these ‘forecasting heuristics’ on the basis of past forecasting accuracy. The interaction between cobweb dynamics and endogenous switching provides an intuitive mechanism that leads to endogenous fluctuations, both in market clearing prices and in the distribution of producers over the different expectation rules. For other contributions in this direction, see for example, Goeree and Hommes (2000), Branch (2002) and Chiarella and He (2003). That the cobweb model has a tendency to result in complicated dynamics is also confirmed by laboratory experiments (see Hommes et al. 2007) and strategy experiments (Sonnemans et al. 2004).

Note that, if producers switch between the stabilizing rational and the destabilizing naïve forecasting heuristic according to a performance measure that also includes past realized profits, policy makers may have an opportunity to stabilize markets. Indeed, Schmitt and Westerhoff (2015, 2017) show that policy makers may set profit taxes such that the more stabilizing forecasting heuristic gains in popularity, thereby calming down complex dynamics. For instance, rational expectations usually require some kind of information costs and may thus be less profitable than naïve expectations – at least at the steady state where predictions of rational and naïve expectations are the same. In such an environment, policy makers should increase profit taxes to reduce the forecasting heuristics’ profitability. In doing so, they promote the use of rational expectations.

The literature discussed so far has focused on the dynamics of a single market. However, another route to complicated dynamics may arise when different markets are coupled and producers can switch between these markets, for example – similar to the mechanism used in the literature on switching between different expectation rules – based upon past (relative) profitability of being active on these two markets. Note that there might be different interpretations for the two markets. They may, for example, correspond to different regional markets for the same homogeneous commodity. Switching then refers to firms specializing on exporting their product to the other region, or even migrating their full production facility to that region. The markets may also relate to two different products that are produced and consumed in the same region, and that can be produced by slight (and cheap) modifications in the production technology. In this case switching means that firms use their productive assets for producing a different commodity.

Dieci and Westerhoff (2009, 2010) are among the first to investigate this switching of firms between markets, which gives a very intuitive explanation for complicated dynamics. To appreciate the mechanism it is important to understand that stability of the cobweb dynamics on an individual market depends upon the sensitivity of the aggregate supply function with respect to the expected price. Suppose aggregate supply responds aggressively to a change in the expected price. In that case a small change in the actual price generates, through producers’ naïve expectations, a strong response from the producers and a price correction that tends to be larger than the initial price change. Now, if individual supply functions are the same for all producers, it follows immediately that an increase in the number of producers active on an individual market increases aggregate supply for each value of the expected price and, by the argument given above, tends to destabilize the price dynamics.

To see how the mechanism works consider two interacting markets, market A and market B, and suppose that the distribution of firms over these two markets is such that market A is more profitable than market B. This will attract firms from market B to market A. The resulting increased aggregate supply sensitivity on market A may very well destabilize that market, generating volatility in market clearing prices. In turn, this decreases profits on market A and there will be a tendency for firms to leave market A and enter market B, which may stabilize the dynamics on market A, but simultaneously destabilizes market B, after which the whole cycle repeats again. Note that we may have a scenario where in the absence of switching both markets are stable under cobweb dynamics, but connecting them by allowing firms to move between markets, makes both of them unstable. This is illustrated by Fig. 1, which considers a setting where, when considered in isolation, both cobweb markets are indeed stable under naïve expectations. The times series in Fig. 1 show that interaction destabilizes the markets. In period 1 firms are almost equally distributed between markets, and although markets are symmetric, profits in market A are slightly higher in period 1. Since the price in market A is below the fundamental value, under naïve expectations we would expect each firm in that market to have a relatively low supply, and that the market clearing price therefore goes up. However, the difference in profits in period 1 leads to an increase in the number of firms in market A in period 2, which increases aggregate supply in that market, and the market clearing price actually decreases and moves further away from the steady state. Similarly, although individual supply under naïve expectations goes up in market B (because of the relatively high price in period 1), aggregate supply decreases because a number of firms move to market A. Also for this market the market clearing price moves away from the steady state. The net effect of these changes is that in period 2 market B is the most profitable and firms move back to market B, and so on. It is important to note that this type of dynamics may even hold if firms only respond to differences in past profits slowly (see also Tuinstra et al. 2014).

Interacting cobweb markets. The panels show the time evolution of prices in market A, profits in market A, prices in market B, profits in market B and the fraction of firms active in market A, respectively. Parameter setting as in Dieci and Westerhoff (2010).

Although complicated behavior in interacting markets arises quite naturally in the case of cobweb dynamics (that is, when producers face a one period production lag and have naïve expectations), this type of behavior occurs more generally. First, also if firms have adaptive expectations the same mechanism may apply. Moreover, even in the extreme case of rational expectations, or alternatively when there is no production lag and the market clearing price is established immediately, the interaction between markets may lead to complicated dynamics, see Schmitt et al. (2017a, b). The dynamics in this case depend upon how responsive firms are with respect to past profits generated by the two regions. Consider, for example, the scenario where there are two markets that, given the number of firms active on the market, are always in equilibrium. That is, firms either have perfect foresight about the equilibrium price after they enter the market, or prices adjust instantaneously and firms do not need to predict the price, but observe it when they make their supply decision. The market equilibrium prices obviously depend upon the distribution of firms over the two markets. If that distribution is such that profits in market A are higher than in market B, firms active in the latter will move to the former. If they respond slowly to the profit differential the distribution of firms will gradually adjust such that in the end profits in the two markets are equalized. However, if firms are sensitive to the profit differential the number of firms moving to market A may be so large that the resulting equilibrium profits in that market become lower than that of market B and firms consequently move back. Through this process of overshooting complicated dynamics may emerge again.

Complicated dynamics also emerge in more elaborate general equilibrium environments. A number of models use a New Economic Geography perspective to model market interactions, for example, Agliari et al. (2011, 2014) and Commendatore et al. (2014, 2015). These contributions show that endogenous fluctuations may emerge from market interactions between different economic regions. Another interesting aspect of these contributions is that they investigate the tools that policy makers have to stabilize fluctuations, for example trading costs. In the next section we review the effect of different types of regulatory policies that may stabilize dynamics in market interaction models with a partial equilibrium flavor as discussed above. As we will see, some of these regulatory policies may also give rise to surprising side effects.

3 Stabilization Policies

Different types of regulatory policies can be implemented to stabilize the erratic dynamics generated by interacting markets. We will briefly discuss two of them here: the imposition of import tariffs between regions (see Tuinstra et al. 2014) and the use of profit taxes (Schmitt et al. 2017a, b).

3.1 Optimal Trade Barriers

Tuinstra et al. (2014) extend the interacting cobweb markets, advanced by Dieci and Westerhoff (2009, 2010), by introducing trade barriers for firms in one region (say region A) that want to export their product to the other region (region B). The size of these trade barriers determines the level of interaction between the markets. On one hand, a prohibitively high trade barrier takes away any incentive for firms in one region to export to the other region, and consequently implies that markets function in isolation. On the other hand, in the absence of any trade barriers there will be free trade and no restrictions on exports. From Dieci and Westerhoff (2009, 2010) we know that the resulting unrestricted interaction between markets may lead to instability, even if markets are stable in isolation. If this is the case it follows that increasing trade barriers sufficiently (for example in the form of import tariffs) may stabilize markets.

However, trade barriers may also come at substantial economic costs. In particular, suppose that firms in region A are more productive, are more numerous and/or face relatively smaller consumer demand, relative to region B. Then, when comparing steady states with and without trade barriers, it follows straightforwardly that although consumers in region A and producers in region B may suffer from free trade, aggregate welfare in each of the regions (and thereby total welfare over the regions) increases. This conclusion is only valid, however, if markets remain stable. The trade-off between increased efficiency at the steady state that follows from diminishing trade barriers, versus the resulting increased instability means that the level of trade barriers that maximizes total aggregate welfare may be strictly positive. This contradicts conventional economic wisdom, which is based on comparing steady state allocations only. Figure 2 illustrates the main point. The figure shows bifurcation diagrams for increasing import tariffs. Starting with a high level of import tariffs it will not be profitable for firms in region A to export their product to region B, although market prices in region B are higher. If the import tariffs decrease firms from region A will start to export to region B, see the lower left panel of Fig. 2. The market clearing price in the latter will decrease, because of increasing supply, and the market clearing price in region A increases (because of decreasing supply). However, if import tariffs decrease too much, the inflow of supply to region B destabilizes that market and fluctuations in prices in both regions and in the export level emerge endogenously. The lower right panel shows aggregate welfare as a function of the import tariff. If the government objective can be characterized by the aim to maximize total aggregate welfare, it follows that the government will choose that level of the import tariff such that market dynamics are ‘just’ stable – that is, any further decrease in trade barriers would lead to welfare decreasing fluctuations. In Fig. 2 this corresponds to an import tariff of about 0.43.Footnote 1 Note that, if the government is incompletely informed, or if the economic environment is subject to regular (demand and/or supply) shocks, this optimal policy may (occasionally) lead to instability as well. Instability may furthermore occur if special interest groups, for example representing consumers and producers from the different regions, lobby for a decrease or increase in trade barriers. Tuinstra et al. (2014) also present a model where trade barriers are endogenously determined by the lobbying efforts of these special interest groups. These efforts depend on the fluctuations in consumer and producer welfare, implying that trade barriers will vary over time. Figure 3 shows a simulation with this model, where import tariffs are revised every sixteen periods (that is, once in a political cycle of four years, if we interpret one period in the model as a quarter). Although the government of region B is in principle able to set an import tariff such that the markets are stable, the effect of lobbying is that the dynamics of prices and export levels becomes highly complicated.

Optimal barriers to entry. The panels show prices in market A, prices in market B, the fraction of exporting firms and average welfare versus import tariffs, respectively. Parameter setting as in Tuinstra et al. (2014).

Import tariffs and lobbying efforts of special interest groups. The panels show the time evolution of prices in market A, prices in market B, import tariffs, and the fraction of exporting firms, respectively. Parameter setting as in Tuinstra et al. (2014).

There have been some other contributions to the literature that have similarly identified a potential trade-off between allocative efficiency on the one hand, and stability on the other. For example, Commendatore and Kubin (2009) show that deregulating labor and product markets may lead to instability and endogenous fluctuations, although it would increase steady state employment. Moreover, recent contributions in the field of New Economic Geography also analyze the effect of trade costs on stability and volatility. Reducing trade barriers, by cutting trade costs, may lead to an increase in instability (see e.g. Agliari et al. 2011, 2014 and Commendatore et al. 2014, 2015). There is also some empirical evidence suggesting a relation between trade openness and volatility. A positive correlation between the two was found by Karras and Song (1996). Moreover, Bordo et al. (2001) argue that the increased incidence of financial and economic crises is due to an increase in deregulation.

3.2 Profit Taxes

As discussed above, Schmitt and Westerhoff (2015, 2017) show that fluctuations on an individual market can be dampened or even fully stabilized by an appropriate level of profit taxes. The intuition is that, in an environment where firms switch strategies on the basis of their past profitability, and instability occurs because firms respond strongly to these profit differences, profit taxes curb the sensitivity with respect to profits. Schmitt et al. (2017a, b) analyze whether profit taxes can have a similar stabilizing effect when there are interacting markets. To that end, they consider a model where there is a large number of firms, and each period all firms have to decide simultaneously on which of the two markets to supply their good. For convenience it is assumed that, after entry decisions have been made, markets immediately adjust such that the market clearing price is established. Therefore there is no production lag and firms are not required to form price expectations. This implies that cobweb dynamics are absent. Equilibrium profits on each market decrease in the number of firms on that market, so firms have to solve a nontrivial coordination problem. If firms are quite sensitive with respect to profit differences the number of firms entering the market that was more profitable in the previous period tends to overshoot the steady state number of firms for that market, and complicated dynamics may emerge. Profit taxes may be introduced to mitigate the response of the firms, thereby slowing down the dynamics and eventually stabilizing it altogether. Schmitt et al. (2017a) and (b) each focus on two potential complications that may come to the fore when regulators contemplate using profit taxes to stabilize interacting markets.

A first complication derives from the observation that profit taxes typically only apply to strictly positive profits. That is, net profits (as a function of gross profits) have a kink at zero, with a slope equal to \( 1 \) for negative profits, and a slope equal to \( 1 - \tau \) for positive profits, where \( 0 \le \tau < 1 \) is the level of profit taxes. This implies that the evolutionary model where firms make entry decisions on the basis of past profits becomes a piecewise (one-dimensional) nonlinear map. These types of maps have been studied extensively in recent years (see Avrutin et al. 2018, for a general introduction and Commendatore et al. 2014, 2015, and Tramontana et al. 2010, 2013 for economic applications) and it turns out they typically give rise to an even richer set of complicated behaviors than smooth nonlinear maps already do.

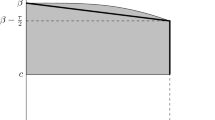

Schmitt et al. (2017a) study the complications that emerge through the kink in the profit function. For convenience they focus on a stylized setting where there is one market and a safe outside option. Profits associated with the outside option are independent of the number of firms choosing that option. Firms have strictly positive fixed costs for supplying in the market implying that profits become negative if too many firms enter the market, and the kink in the profit function then becomes relevant.

As long as profits remain strictly positive an increase in the sensitivity of firms with respect to profit differences will destabilize the dynamics through a so-called period doubling bifurcation and the fraction of entrants oscillates between a high and a low value. However, due to the kink in the profit function it turns out that a high-amplitude period two cycle already exists when the steady state is locally stable. For some parameter values this high-amplitude period two cycle coexists with the locally stable steady state, and for other parameter values it coexists with a low-amplitude period two cycle. This coexistence of attractors leads to a number of intriguing dynamical phenomena. For example, a small decrease in the profit tax rate may lead to abrupt changes in the dynamics, because suddenly the low-amplitude period two cycle ceases to exist and the dynamics is attracted to the high-amplitude period two cycle. This is illustrated by the upper two panels in Fig. 4, which show that a decrease of the profit tax rate from 0.5 to 0.4 drives the dynamics to a high-amplitude period two cycle. It may prove difficult for the government to correct for this. Increasing the profit tax rate to its initial value typically does not suffice, as is confirmed by period 41–60 in the second panel of Fig. 4 and the corresponding dynamics in the first panel. A much higher increase in the profit tax rate may be required. This hysteresis effect is due to the kink in the profit function and turns out to be very robust to changes in the model. It imposes some important restrictions on stabilizing markets through profit taxes that regulators should be aware of. Even if the profit tax rate is constant over time interesting dynamical phenomena may emerge. The lower two panels of Fig. 4 show the dynamics when the tax rate is constant at 0.5 but where stochastic shocks hit the dynamical system occasionally. These shocks may move the dynamics from the basin of attraction of one of the coexisting attractors to that of the other attractor. The fluctuations that may emerge can be quite complicated, as illustrated by the third panel of Fig. 4.

Time evolution of firms active in market A and the profit tax rate in market A. The first two panels illustrate the hysteresis effect, the latter two panels show the dynamics with occasional exogenous noise, with constant tax rates. Parameter setting as in Schmitt et al. (2017a).

Schmitt et al. (2017b) consider a variation of the model used by Schmitt et al. (2017a) with two important changes. First, the outside option is explicitly modelled as a different market, and second, firms have no fixed costs. The implication of the second adjustment is that firms will never make losses and therefore there is no kink in the profit function. This makes the model more suitable for understanding the effect of profit taxes in the two different markets (or regions) on the stabilization of complicated dynamics and on (the distribution of) welfare in the two different markets, which is exactly the aim of that paper.

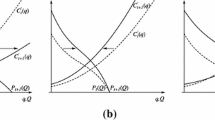

By imposing a profit tax in both regions volatile market dynamics can be stabilized, see the first two lines of Fig. 5. The first line shows the effect of the so-called intensity of choice, a parameter that measures how strongly firms respond to profit differentials. The profit tax rates are zero in both regions, and an increase in the intensity of choice induces instability (left panel), which decreases total average welfare (right panel). The second line shows that this instability can be reversed by increasing profit tax rates in both regions (note that the intensity of choice parameter used in the second line corresponds to the maximum value in the panels on the first line).

The first two lines show bifurcation diagrams for the fraction of firms in region A and average welfare as a function of the intensity of choice (profit tax rate is zero), and as a function of the profit tax rate, taken to be equal in both regions. For the third (fourth) line the profit tax rate in region B is zero (0.5) and the profit tax rate in region A varies. The intensity of choice parameter equals 27 in all graphs (except for those on the first line, where this parameter varies from 0 to 27).

It turns out that, in the symmetric setting of the model, in order to stabilize the dynamics it will be sufficient to introduce a profit tax in only one of the two regions. The third line of Fig. 5 shows the case where only region A imposes a profit tax rate (again with intensity of choice equal to 27). Although the profit tax rate in region A that is required to stabilize the dynamics is higher than before, stabilization of the dynamics is still possible. However, because the difference in profit tax rates distorts the steady state distribution of firms between regions total aggregate welfare is not maximized in this way. If the aim of the regulators is to maximize average welfare aggregated over the two regions it is better to coordinate on profit taxes and set them at the same (sufficiently high) level (see the fourth line of Fig. 5, where total average welfare is maximized when both regions set a tax rate of 0.5). Such a coordinated tax policy may be difficult to achieve in practice, since regulators in each region will have the incentive to reduce the profit tax and thereby attract more firms to their region. Although this may lead to instability, it will also increase tax revenues for the consumers in that region and the net effect may be beneficial. In this way, a coordinated tax policy could easily unravel and the regions then become trapped into a regime with volatile markets and low welfare levels.

4 Conclusions and Outlook

In recent years the interaction between individual markets has received attention for its role in reinforcing, or even creating, instability and complicated endogenous dynamics. In this chapter we have reviewed some of the mechanisms that have been identified, as well as the effect of stabilization policies that have been put forward.

Tuinstra et al. (2014), for example, show that market interaction may imply that, although import tariffs between markets may decrease allocative efficiency at the steady state equilibrium, such tariffs may be welfare enhancing nevertheless. This is because they weaken the link between markets and thereby stabilize consumption and production patterns. Schmitt et al. (2017a, b) investigate how the introduction of profit taxes may stabilize interacting markets where firms responds strongly to past profit differences. Schmitt et al. (2017a) argue that profit taxes result in an additional nonlinearity in the dynamics (a kink of the profit function at zero), which introduces complicated dynamics such as coexistence of attractors and hysteresis. Schmitt et al. (2017b) discuss the scenario where each region is overseen by an independent local government or regulatory authority. Optimally, these two regulators coordinate their profit taxes in such a way that markets are stable and total welfare is maximized. However, Schmitt et al. (2017b) argue that, if regulators are only (or mainly) interested in welfare in their own region, each of them will have the incentive to decrease the profit tax, which can destabilize markets.

We conclude this chapter by briefly discussing several possible extensions to the work discussed here. One extension is to present the tax competition discussed in Schmitt et al. (2017b) as a game between the regulators of the two regions, where each regulator independently sets the profit tax rate for its own region with the goal to maximize average welfare in that region. The question then is under which conditions the Nash equilibria of this game are characterized by unstable market dynamics and suboptimal global welfare levels. Other interesting extensions naturally follow from the observation that the models that we discussed in this chapter are quite stylized. One simplifying assumption has been to consider a partial equilibrium framework. An obvious question is whether the main insights discussed in this chapter will also be valid in a full-fledged general equilibrium model. Moreover, thus far we have only looked at interaction between markets on the supply side. New insights may be obtained if markets are also connected through consumer demand. Similarly, it makes sense to consider models that depart from the assumption that producers can migrate free of any costs between markets or regions and that consumers are fully immobile. Relaxing these assumptions may to a certain extent mitigate some of the adverse effects of stabilization policies on stability, although we believe the basic mechanism will survive the generalizations discussed here.

References

Agliari, A., Commendatore, P., Foroni, I., Kubin, I.: Border collision bifurcations in a footloose capital model with first nature firms. Comput. Econ. 38, 349–366 (2011)

Agliari, A., Commendatore, P., Foroni, I., Kubin, I.: Expectations and industry location: a discrete time dynamical analysis. Decis. Econ. Finance 37, 3–26 (2014)

Avrutin, V., Gardini, L., Schanz, M., Sushko, I., Tramontana, F.: Continuous and Discontinuous Piecewise-Smooth One-Dimensional Maps: Invariant Sets and Bifurcation Structures. World Scientific, Singapore (2018)

Bordo, M., Eichengreen, B., Klingebiel, D., Soledad, M., Martinez-Peria, M.S., Rose, A.K.: Is the crisis problem growing more severe? Econ. Policy 16, 51–82 (2001)

Branch, W.A.: Local convergence properties of a cobweb model with rationally heterogeneous expectations. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 27, 63–85 (2002)

Brock, W., Hommes, C.: A rational route to randomness. Econometrica 65, 1059–1095 (1997)

Brock, W., Hommes, C.: Heterogeneous beliefs and routes to chaos in a simple asset pricing model. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 22, 1235–1274 (1998)

Bullard, J.: Learning equilibria. J. Econ. Theory 2, 468–485 (1994)

Chiarella, C.: The cobweb model – its instability and the onset of chaos. Econ. Model. 5, 377–384 (1988)

Chiarella, C., He, X.Z.: Dynamics of beliefs and learning under a(L)-processes – the heterogeneous case. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 27, 503–531 (2003)

Commendatore, P., Kubin, I.: Dynamic effects of regulation and deregulation in goods and labor markets. Oxford Econ. Papers 61, 517–537 (2009)

Commendatore, P., Kubin, I., Petraglia, C., Sushko, I.: Regional integration, international liberalisation and the dynamics of industrial agglomeration. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 48, 265–287 (2014)

Commendatore, P., Kubin, I., Sushko, I.: Typical bifurcation scenario in a three region symmetric New Economic Geography model. Math. Comput. Simul. 108, 63–80 (2015)

Dawid, H., Kopel, M.: On optimal cycles in dynamic programming models with convex return function. Econ. Theory 13, 309–327 (1999)

Day, R.H., Huang, W.H.: Bulls, bears and market sheep. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 14, 299–329 (1990)

Dieci, R., Westerhoff, F.: Stability analysis of a cobweb model with market interactions. Appl. Math. Comput. 215, 2011–2023 (2009)

Dieci, R., Westerhoff, F.: Interacting cobweb markets. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 75, 461–481 (2010)

Ezekiel, M.: The cobweb theorem. Q. J. Econ. 52, 255–280 (1938)

Goeree, J.K., Hommes, C.H.: Heterogeneous beliefs and the non-linear cobweb model. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 24, 761–798 (2000)

Grandmont, J.M.: On endogenous competitive business cycles. Econometrica 53, 995–1045 (1985)

Heemeijer, P., Hommes, C., Sonnemans, J., Tuinstra, J.: Price stability and volatility in markets with positive and negative expectations feedback: an experimental investigation. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 33, 1052–1072 (2009)

Hommes, C.H.: Dynamics of the cobweb model with adaptive expectations and nonlinear supply and demand. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 24, 315–335 (1994)

Hommes, C.H.: On the consistency of backward-looking expectations: the case of the cobweb. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 33, 333–362 (1998)

Hommes, C., Sonnemans, J., Tuinstra, J., van de Velden, H.: Coordination of expectations in asset pricing experiments. Rev. Finan. Stud. 18, 955–980 (2005)

Hommes, C., Sonnemans, J., Tuinstra, J., van de Velden, H.: Learning in cobweb experiments. Macroecon. Dyn. 11, 8–33 (2007)

Huang, W.: The long-run benefits of chaos to oligopolistic firms. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 32, 1332–1355 (2008)

Karras, G., Song, F.: Sources of business-cycle volatility: an exploratory study on a sample of OECD countries. J. Macroecon. 18, 621–637 (1996)

Kopel, M.: Simple and complex adjustment dynamics in Cournot duopoly models. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 7, 2031–2048 (1996)

Lux, T.: Herd behavior, bubbles and crashes. Econ. J. 105, 881–896 (1995)

Matsumoto, A.: Let it be: chaotic price instability can be beneficial. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 18, 745–758 (2003)

Puu, T.: Chaos in duopoly pricing. Chaos, Solitons Fractals 1, 573–581 (1991)

Schmitt, N., Tuinstra, J., Westerhoff, F.: Side effects of nonlinear profit taxes in a behavioral market entry model: abrupt changes, coexisting attractors and hysteresis problems. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 135, 15–38 (2017a)

Schmitt, N., Tuinstra, J., Westerhoff, F.: Stability and welfare effects of profit taxes within an evolutionary market interaction model. Review of International Economics, forthcoming (2017b)

Schmitt, N., Westerhoff, F.: Managing rational routes to randomness. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 116, 157–173 (2015)

Schmitt, N., Westerhoff, F.: Evolutionary competition and profit taxes: market stability versus tax burden. Macroeconomic Dynamics (2017). in press

Shiller, R.: Irrational Exuberance. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2015)

Sonnemans, J., Hommes, C., Tuinstra, J., van de Velden, H.: The instability of a heterogeneous cobweb economy: a strategy experiment on expectation formation. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 54, 453–481 (2004)

Theocharis, R.D.: On the stability of the Cournot solution to the oligopoly problem. Rev. Econ. Stud. 27, 133–134 (1959)

Tramontana, F., Westerhoff, F., Gardini, L.: On the complicated price dynamics of a simple one-dimensional discontinuous financial market model with heterogeneous interacting traders. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 74, 187–205 (2010)

Tramontana, F., Westerhoff, F., Gardini, L.: The bull and bear market model of Huang and Day: some extensions and new results. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 37, 2351–2370 (2013)

Tuinstra, J., Wegener, M., Westerhoff, F.: Positive welfare effects of trade barriers in a dynamic partial equilibrium model. J. Econ. Dyn. Control 48, 246–264 (2014)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

Schmitt, N., Tuinstra, J., Westerhoff, F. (2018). Market Interactions, Endogenous Dynamics and Stabilization Policies. In: Commendatore, P., Kubin, I., Bougheas, S., Kirman, A., Kopel, M., Bischi, G. (eds) The Economy as a Complex Spatial System. Springer Proceedings in Complexity. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65627-4_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65627-4_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-65626-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-65627-4

eBook Packages: Physics and AstronomyPhysics and Astronomy (R0)