Abstract

The identification of lone-parent households is a challenging task in an era of new family forms and related changes in the legislation regulating parental care and financial responsibilities. Official statistics hardly reflect the composite reality of households between which children circulate and in which relationships with biological and non-biological parents change during the life course. On the basis of an explorative qualitative study in Switzerland, we focus on the blurry boundaries used to define the transition to lone parenthood. We analyse the life course of individuals whose entry into the lone-parent state fits one of these patterns: (a) becoming a lone parent despite beginning parenthood within a couple (separation, divorce, or widowhood); (b) becoming a lone parent coinciding with becoming a parent (contraceptive failure, partner refusal of parenthood, or lone parenthood as a life choice). We explore the way in which individuals describe their transition to lone parenthood and to which extent they identify themselves as lone parents. We conclude that such transitions are often non-linear processes and are often characterized by much ambivalence. They involve an array of heterogeneous and multidirectional transitions that are not always captured by current surveys, and we suggest how we could improve future measurements of the timing and occurrence of lone parenthood.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Variety of Transitions into Lone Parenthood

The rise in lone-parent households is part of the growing diversification of household types, living arrangements, and family forms that have presented in Europe over the last 40 years. In 2009 in Europe, the share of lone-parent households (calculated as the proportion of households with children under 18) ranged from 5–7% in countries like Greece, Spain, Romania, and Slovakia to 20–24% in countries like Estonia, Latvia, Ireland, and the United Kingdom (Chzhen and Bradshaw 2012, p. 490). In Switzerland, the last available survey data from 2013 indicated that 15% of households with children under 25 had one parent. More than 80% of these situations regard lone mothers (2015).Footnote 1 Despite lone-parent households representing a minority of households, researchers are interested in them for two reasons. On the one hand, lone-parent households are considered at risk and are often mentioned when talking about family risks, particularly economic and health risks (Bonoli 2005). On the other hand, they are an alternative living arrangement increasingly contributing to the family diversity that characterizes contemporary families.

Research on lone parents in Europe, which rests on analyses of nationally representative, large-scale surveys, has shown that lone parents are different from other parents in terms of socioeconomic and health characteristics. Lone parents have higher risks of negative outcomes (poverty, unemployment, health) than parents in couple. This is particularly true for lone mothers but less so for lone fathers. Lone parents are also much more likely to be social assistance recipients or to benefit from social housing and health insurance benefits (Whitehead et al. 2000). Children in one-parent families have a much higher risk of living in poverty or social exclusion than dependent children in two-adult families. Around half of one-parent households with dependent children were at risk compared to only about one-fifth of households with two adults and two dependent children (Lopez Vilaplana 2013). Lack of resources (financial but also psychological and social) and a limited capacity to recover from stresses in other life domains (work in particular) are factors of lone parents’ vulnerability. A number of qualitative studies devoted to lone parents, especially in France, the UK, and the United States, have shown that besides the vulnerability associated with lone parenthood, there exist important aspects of resilience triggered by the lone-parenthood experience. In the Anglo–Saxon context, teenage lone mothers from disadvantaged backgrounds hold a positive attitude toward motherhood as turning point in life that allowed them to take a different direction, including going back to education and work (Bell et al. 2004; Coleman and Cater 2006; Duncan 2007; Edin and Kefalas 2011; Phoenix 1991; SmithBattle 2000). Lone mothers and parents who coupled represent equally positive parental role models (Dowd 1997). Research in continental Europe has additionally brought to attention that the population of lone mothers is much more varied than its perception as simply a population composed only of low-educated adolescent mothers. Such research has consistently shown that lone mothers are not only overrepresented in social welfare compared to mothers in a couple but also are more likely to work, and to work full time, than mothers in a couple (Struffolino et al. 2016); it may be of interest to researchers that lone mothers are more likely to reside in poorer districts but also in more well-off ones than mothers in a couple (Lefaucheur and Martin 1997).

What emerges clearly from previous research is that lone parents constitute a very diverse and heterogeneous group and much of this diversity depends on the way lone parenthood is produced and when it occurs in the life course. The most common pathways to becoming lone parent are through divorce or separation, widowhood, and pregnancy or adoption by individuals not in a couple. While widowhood was the privileged path to lone parenthood in the past (Kiernan et al. 2004), with growing union instability, marital break-ups are the primary cause of parents raising children alone for some time in their lives. Besides material and health deprivation, family researchers are interested in lone parents because they represent a nonnormative way of being parents that affects a growing number of children, at least during part of their childhood. Lone parenthood is nonnormative not only because it concerns a minority of parents (although it is a growing minority) but also because shared norms about parenthood in Europe still largely indicate that two parents and children living together is preferable and more appropriate. This is also because being a lone parent is only rarely a planned and a chosen way to parenthood; more often, it is an unexpected or unintended turning point in life.

The lone-parenthood experience itself varies depending not only on the material and social resources available to parents and children but also on the specific legal arrangements with the nonresident parent (provided that he or she is living and available), such as arrangements for child custody, parental authority, and child support. The age and the number of children are important aspects related to this experience. Although quantitative data and analyses are certainly necessary to gain an understanding of family structures and processes that can be generalized across populations, qualitative studies are critically important to formulating new hypotheses and theories about new family forms. In-depth knowledge from a few cases can be used to do so (Bernardi and Hutter 2007; Ragin and Becker 1992). Analyses of qualitative data provide us with answers regarding how some processes take place, which is critical to theory development. Last, the measurement of lone parenthood in surveys requires standardization; we know that estimates of the prevalence of lone parenthood are affected by how it is measured (Letablier 2011).

For all these reasons, we aim to contribute to the understanding of lone-parent families’ experiences through a qualitative study based on semistructured interviews. In Switzerland in 2013–2014, we interviewed women and men who had recently faced an experience of lone parenthood with full custody of their young children. We focused on the transition to lone parenthood and its boundaries from a life-course perspective. In the life-course tradition, transitions are defined as periods of rapid change in the life course when individuals redefine one or more of their social roles and pass from one phase to another. Transitions may represent turning points in life when they challenge and redefine future expectations and trajectories in fundamental ways. The process is not necessarily unidimensional and unidirectional, and a qualitative study is crucial to pointing out the challenges of identifying ways to model and measure lone-parenthood trajectories appropriately and improve the quality of our data about this increasingly important family form. At what point can we consider lone parents as such? Is it at separation due to discord, at formal residential separation, or at the moment when the financial and legal responsibilities for the child are assigned to one parent? Through this examination of the transition into lone parenthood, we aim to contribute to the understanding of what events and circumstances can be best considered as defining the onset of lone parenthood.Footnote 2

Background and Significance

Who are lone parents? Lone-parent households are not easily and univocally identifiable since their definition varies from country to country and from data source to data source. The most comprehensive definition includes households where one parent coresides with his or (more often) her children and bears the financial responsibility for the children alone, irrespective of whether other adults coreside in the household. Surveys often have more restrictive distinctions, which exclude situations where a parent resides with his or her children and a new partner, or with his or her children and their grandparents, other family members, or unrelated adults. Other criteria, which may vary, are a child’s age (some data sources limit it to age 16, 18, or 25 to qualify a household as a lone-parent household). In Switzerland, the official statistics of the Federal Statistical Office recently distinguished the households in which at least one child under 25 lives with one parent alone as a specific living arrangement (Mosimann and Camenisch 2015). Other than this official descriptive criterion, there is no legislation addressing lone-parent households as such.Footnote 3

Research dealing with lone parenthood in demography is concentrated on lone parents as defined by the type of household or living arrangement. More recently, and thanks to the availability of longitudinal data, pathways to and out of lone parenthood have concentrated on the typology of individual union and employment trajectories before and after lone parenthood (Bastin 2013; Schnor 2013; Struffolino and Bernardi 2017). Most of these studies identify a date of entry into lone parenthood as if there were a straightforward time marker for it, ignoring the complexity and the number of events involved in the transition process.

Yet, the onset of lone parenthood is likely to be a fuzzy process. The difficulties in identifying lone parents emerge from at least two distinct sources: one relating to the partnership status and the second relating to the parenting responsibilities and practices. First, the kind of noncoresidential partnership may vary depending on the arrangements between the members of a couple or the financial and emotional involvement of the partner with the children. Consequently, establishing the extent to which lone parents are “alone” is an empirical question. Second, independent of the possible involvement of a new partner, a second set of difficulties in the identification of what lone parents are comes from the assumption of parenting responsibilities and the residential and care arrangements for children. When children circulate across two parents’ households according to more or less fixed schedules and more or less formalized agreements, what is the status of those parents who formally have the custody and legal responsibility for children? In addition to these objective difficulties related to residential and legal arrangements, the identification of individual parents as being alone in assuming parental responsibility—financially, educationally, and emotionally—complicate the picture even further.

Given the importance of the timing and sequencing of events—both as independent and dependent variables—in demographic and social-policy analyses, it is important to understand how the transition to and out of lone parenthood is defined and experienced. The boundaries between couple-parenthood and lone-parenthood cohabitation may be much blurrier than is generally assumed. In this regard, lone-parenthood endings may also be blurred, not unidirectional, and often involve ambivalence and gradual entry into a new relationship.

Our study is an ongoing project that aims at capturing both the diversity of pathways into lone parenthood and the subjective experiences of being a lone parent in Switzerland through a mixed-methods design. The quantitative part, based on longitudinal survey data, describes and analyses trajectories in and out of single parenthood as well as analysing specificities of lone parents in comparison to nonparents and cohabiting or married parents with similar characteristics (e.g., Struffolino et al. 2016). In the qualitative part of the project, we are interested in the objective adjustments one takes when entering the new lone-parent status, arrangements for the daily care for children, in working life, and in relational life. The subjective recognition of one’s own state of lone parenthood takes time; it is often nonlinear and marked by ambiguity toward the role of main carer for the children and ambivalence in the acceptance of such a role. For this chapter, we restricted the analysis to the crucial aspect of defining the boundaries of the transition to lone parenthood and how parents define lone parenthood. In particular, we draw on a set of semistructured interviews with parents who identified themselves as “parents raising their children alone” at the moment of the interview in order to show the challenges in defining the beginning and the end of a lone-parent status. In lone parents’ discourses about their transition to lone parenthood, objective residential arrangements, legal arrangements, and subjective feelings about their relationships and about the ways in which caring is shared are all important elements of the definition.

Data and Methods

We analysed 40 open-ended interviews reconstructing the life course of individuals who, at the moment we met them, were living as lone parents (i.e., men and women who identified themselves as parents raising their children alone). All the respondents lived in urban settings in the two Swiss cantons of Geneva and Vaud.Footnote 4

We purposively built our sample to explore a variety of lone-parenthood experiences. In particular, we aimed at having variations in the patterns of entry into lone parenthood. One group of respondents entered lone parenthood as a consequence of having lost their partners, either through union breakup or a partner’s death. In both cases, parenthood was experienced while in partnership and followed by separation, divorce, or widowhood. When the other parent was alive, we included cases in which parents were in contact with each other on a regular basis and cases where contacts were occasional or absent (either because of conflict or because of important geographical distance). The important aspect here is that parenthood began as a couples’ experience, transformed itself through the separation and postseparation processes, and had to be unmade and rebuilt under a different configuration of relationships. A second pattern is represented by a transition to lone parenthood that began as a lone experience and not within a couple. These are cases of unplanned children conceived because of contraceptive failure with an occasional partner, cases in which a partner has not accepted the role of a parent from the very start, or, more rarely, conceptions obtained through a donor. Often in these circumstances, the mother experiences lone parenthood beginning at the birth of her child. In other cases, the nonresident parent may have existed and known about and had occasional contact with the child. Parenthood then “belongs” to the individual from scratch and is constructed as an individual experience throughout.

The 40 respondents we interviewed were recruited through a multiple-entry snowballing technique. Initial seed individuals were reached through personal contacts, mailing lists from lone parents and family associations, researchers’ contact boxes at a kindergarten, and flyer distribution in public places visited by parents and children. Entering the field was, as often happens, a gradual process. Flyers and mailing lists did not produce as many results before we entered contact with the family associations and before the word spread among lone parents’ own contacts through snowballing. This technique has the advantage of reducing self-selection and reaching out to individuals who would not otherwise be willing to answer an anonymous phone call or e-mail from someone requesting participation in a survey. The fact that we gathered our initial contacts from several different sources reduces the biases that may occur when interviewing only a group of people in contact with each other, who could be similar to each other and therefore give access to only a specific experience of lone parenthood.

We also limited the interviews to parents who experienced a relatively recent transition to lone parenthood (mostly within 1–5 years), who had in most cases a child aged between 0 and 10 years,Footnote 5 and who had full legal custody of their children as much as possible. These choices were made after a pilot study with larger inclusion criteria, which showed that recalling transitions happening further in the past was not easy, and lone parenthood when children are older and more autonomous is a completely different experience. In addition, the focus on recent transitions is justified by the fact that our longitudinal setup will enable us to follow the evolution of our lone parents in the medium run (up to 4 years from the previous interviews) and to understand the effects of duration on lone parenthood and the process of exiting lone parenthood. The focus on younger children is justified by the fact that these are children who still require a relatively high amount of care (i.e., they need continuous adult supervision). We did not include cases in which child custody was equally shared between the two parents, since coparenthood implies a different kind of relationship among parents and parents and children, and we wanted to limit our sample to lone-parenthood situations.

Interviews were extensive; on average they lasted 90 min. The sensitive nature of the topic caused emotionally intense experiences for both respondents and interviewersFootnote 6 at times. Participants were asked to sign an informed-consent form, which sometimes generated concerns, even in cases in which parents happily agreed on being interviewed. The interviewing team was composed of experienced researchers. The team met regularly to adjust the interview guidelines with the experience gained in the field and to discuss specific cases and situations that challenged our questions and methods.

The interview content began with questions designed to create sketches of the participants’ life-course trajectories in different domains (union, family, education, and employment). We then asked participants to place parenthood and the transition to lone parenthood in the context of the life course. We probed for different topics: the evolution of the relationship with the other parent (when appropriate) and of his/her relationship with the child/children; the relationship of the child/children with the respective parents’ families; the current legal arrangements for the child/children; the possible employment adjustments related to lone parenthood; the role of institutional support in the transition and afterwards; the daily-life organization and childcare arrangements; the perceived advantages and disadvantages of lone parenthood; the partnership situation at the moment of the interview; and the current network configuration and social support.

We used a semistructured interview guideline. The openness also allowed for exploring the justification given for any behavioural patterns, meanings attributed to choices, and perceptions and expectations. All of these elements were crucial to understanding family-related processes described by statistical analyses. Each interview was tape recorded (after receiving participants’ consent) and transcribed verbatim. The analysis of material was driven by the research question (What is the respondent’s description of his or her transition to lone parenthood? What are the markers of the transition to lone parenthood he or she introduced as crucial in the process?). Even though the interview guide was the same, the themes emerged at different stages along the conversation. Analyses are interpretative and based on comparisons of individual cases and cross-case thematic coding. Top-down coding—based on the topic guide—and bottom-up coding—generated by spontaneous parts of the interview—were combined to produce categories that identified the salient characteristics defining the transitions to lone parenthood (Corbin and Strauss 1990).

Findings: Marking the Transition to Lone Parenthood

The main question of interest in this paper regarded how lone parents defined lone parenthood and what they identified as the marker or the markers of such a transition. The rationale was to ensure that we produced valid survey indicators to analyse transitions into and out of lone parenthood. Transition markers that we usually found in surveys may have diverged greatly from subjective markers of lone parenthood indicated as salient by the lone parents we interviewed. Under these circumstances, modelling the transition to lone parenthood in a valid way was an open challenge. In the next section, we report the way in which interviewees marked their transition to lone parenthood. We have three sets of cases: First, we have cases in which respondents identified a number of markers that corresponded to objective and easily recordable events (end of cohabitation and legal separations for instance). Second, we have a large number of cases in which parents referred to changes in their lives that for them were pivotal in marking the onset of lone parenthood but were not often used to model the transition to lone parenthood (e.g., realising that one will have to care for the children alone, in-house separations, inner resolution to assume parenthood alone). The degree of correspondence between the way in which parental responsibilities are formally agreed on and the way in which they are arranged on a day-by-day basis varied substantially (e.g., parents with formal full custody and authority who actually lived in a situation of shared custody and did not feel they were lone parents and vice versa). Third, we examined cases in which the boundaries between couple parenthood and lone parenthood were blurred for the interviewee him or herself and in which individuals were ambivalent about their status as lone parents.

In what follows, we flesh out our argument by illustrating each of these situations with individual cases.

Objective Markers Usually Used in Modelling Union and Family Transitions

In a number of cases, residential and legal markers (residential separation, legal separation, decisions about the financial responsibilities for children, the children’s custody, and authority) are sufficiently clear-cut to allow parents to refer to them as marking the start of lone parenthood. An objective marker of another nature is the diagnoses of pregnancy for women not in a relationship. Typically, interviewees identified a series of circumstances and described the transition toward lone parenthood as a gradual process composed of several events, making it clear that the transition to lone parenthood is multidimensional.

Case No. 1

Antoinette (legal separation): “I knew already that there was something that did not work, but putting words to it ... I knew it did not work but I did not have the courage to leave...” She was a housewife or worked occasionally until she found a full-time job but left to go back to school. This accelerated the crisis of her marriage: “He did not accept the separation. He said to the judge that I should absolutely not work because it is impossible to study and raise the children; she must stop studying.” The separation was formalized 1 year later, and it is this official date that Antoinette cites as the beginning of her lone parenthood (Antoinette 41, two children aged 13 and 16).

Case No. 2

Céline (residential separation): Céline has been in a relationship and cohabiting with a man for about 6 years. She became the mother of two children but after the second child, she definitely realized that the relationship with her partner was gradually deteriorating. 2 years after the birth of their second child and after several attempts to make her relationship work again, she decided to break up with her partner. Her residential separation from the partner marked the watershed in this story: “I think the birth of the kids did not ... did not help our relationship ... We wanted to have children, but it’s true that afterwards there was no more feeling in our relationship ... Sometime after the birth of the second ... we were parents, but as to our relationship we were living as ... I don’t know, as friends ... we could perfectly deal with everyday family life but there was nothing more in our life as a couple ... We tried to find the means ... we did not ask for help, but we have tried ... but we did not succeed ... and then we decided to separate in October 2010 ... At the beginning, I wanted to keep the flat, it was a four room flat, and he would find a smaller one, but then I found [one] by chance.” Since then, Céline has had full custody of her children and receives regular payments from her expartner: “Yes, he gives me what we stated in the partnership agreement, then he takes them one evening every week and once every two weekends ...” (Céline 34, two children aged 4 and 6).

Relational and Subjective Markers of the Transition to Lone Parenthood

Some of our stories speak about lone parenthood as starting with in-house separation, in which the parents still live together but one of the two clearly withdraws from his or her role both as a parent and as a partner. Here, the timing is more diffused. It refers to relational changes rather than factual events: the other parent begins a new relationship, the worsening of conflicts or the interruption of contacts between parents, and a growing inner resolution to assume parenthood alone.

In Marie-Jo’s account and, more dramatically, in Arthur’s story, (both of their cases are described below) residential and legal objective markers occur much later than the beginning of their lone parent status. In such situations, the relationship as a couple is nonexistent and only one parent actually cares for the children, despite the fact that the parents continue to cohabit. These couples would be coresidents and even married in the case of Arthur, and they officially share responsibilities and rights for the children.

Case No. 3

Marie-Jo (in-house separation): Marie-Jo was in a relationship with a man whom she began to live with soon after they met. Her partner convinced her to have a child together, but once she was pregnant, he seemed to have lost interest in parenthood. This became evident when she entered her sixth month of pregnancy. According to Marie-Jo, “The situation became very difficult at home ... I think I have lived through this pregnancy alone ... We were living under the same roof, but we would not meet each other. He started sleeping in the other room. He would go to work early in the morning, he would come home late ... I mean [we were] not even housemates.” The situation remained the same until the child was 6 months old: “He (the partner) would come home in the evening ... he would not even hold the baby in his arms ... he would hardly look at her.” Marie-Jo dates the beginning of her lone parenthood from a long time before the residential separation, which happened when the baby was 6 months old. To her, the transition started when the father of the child began withdrawing from his role as a partner and as a father simultaneously. She experienced his leaving the common household as the inevitable consequence of her lone parenthood, not its onset. Despite the father financially contributing the sum of money legally established, he has not seen his daughter since the separation. Marie-Jo feels that she was the only parent caring for her daughter since her birth. All in all, Marie-Jo’s residential trajectory does not overlap with her trajectory as a lone parent (Marie-Jo, 37, one child, aged 5).

Case No. 4

Arthur (in-house separation): Arthur has the custody of his two daughters of 5 and 3 (they were 2 and 4 when the parents wanted to break up). When his wife left the apartment, he started filling out the paper work for a formal separation, which was not ready when she decided to move in again after 6 months: “The lawyer said she has the right to come back home. So she came back but meanwhile she had started a new life. I have to say that I was alone to care for the children. There was absolutely no love anymore. So it was extremely difficult when she came back, just impossible to bear it…. It was difficult in relation to the children, because I prepared them, I told them, I explained to them, but the fact that they saw her coming back, it was difficult, in the sense that they thought ‘ah, here they come back together.’” Arthur’s wife used to bring her temporary relationships to their home, leaving Arthur to care for the children as if he were alone. The tension between them rose to the point that she tried to stab Arthur in front of the children. Only at that point could legal measures be taken to oblige the mother to leave the common household (Arthur, 31, two children aged 5 and 3). In such situations, it may happen that legal and residential markers of lone parenthood do not correspond to the parents’ daily arrangements or their understandings of the situation.

Case No. 5

Anouk (residential separation but formally shared parenting): Anouk’s lone parenthood status was hidden by the formal shared custody. Anouk separated from the father of her child in 2011 due to his alcohol addiction. She simply moved out. She does not receive any alimony and there is no legal arrangement about the father’s visiting rights given that what was legally foreseen in the case of separation was shared custody and authority. In reality, the father does not care for the child regularly. Social services workers know that Anouk has troubles claiming maintenance payments from her partner due to his alcohol addiction, but since the father has never abused the child they refuse to mediate. The only way for Anouk to have her rights recognized would be to go to court and ask for a change in the legal arrangements, which she is not ready to do since she is still very much emotionally connected to the father of the child. She prefers to find her own way to regulate parental responsibilities, independently of what the laws say: “So I said, ‘okay, you can have your son every week, one day in the weekend, and one day on weekdays, there is no problem, when you want,’ but he had to show me that he was sober. So we set up a system whereby I would make him take a breathalizer test. I had ... a device, and so I was a controller” (Anouk, 41, 1 child, aged 4).

Case No. 6

Susan (residential separation but formally shared parenting): The case of Susan illustrates a similar incongruence between legal and actual arrangements. Subjectively, the transition to lone parenthood for Susan started with the resolution to leave the country of common residence and return to Switzerland. However, no objective markers of transition can be tracked down, as she is still formally married according to African law and has no legally registered children according to Swiss law. Susan has lived as a lone parent in her daily life for a year, but the separation from her husband has not yet been formalized. She worked and lived for 10 years in Africa where she met the father of her children, who still works seasonally there. After a five-year relationship, they had the first unplanned child and then a second intended one, as a couple. Susan felt that their relationship was not working anymore after this second birth and returned to Switzerland with the children to have her mother’s help with childcare. Despite being de facto separated for a few years at the moment of the interview, she has not started any formal separation from her husband yet: “So we did not start any formal procedure to end the separation process, and even if we did, we know that it would be complicated ... to arrange something regular. Because ... he has a job that is not regular.” In addition, due to administrative complications, her children do not have official documents either as foreigners or as Swiss nationals. This is despite the fact that they attend school regularly as residents of a Swiss territory; otherwise, they are not officially acknowledged by the Swiss government (Susan, 36, two children, aged 7 and 5).

Case No. 7

Catalina (flexible custody arrangements): In contrast to Anouk’s and Susan’s cases, there are situations in which lone parenthood is formally recognized but parental practices imply day-by-day shared parental arrangements. Catalina, a mother of a six-year-old child, is actually closer to living in a shared custody situation than being a lone parent. Catalina separated from her cohabitant partner when her daughter was 6 months old and has formally obtained full custody and authority over her child. She said, “He has the right to visit her ... every Thursday evening ... and one [out of] every two weekends.” However, when reporting on her day-to-day parental practices, we find out that on many occasions, the formal custody agreement is completely reversed. She said, “It was good for me that he was not working in a way ... because last year, he took her during the whole school break.... Yes, the whole week, and I would stay with her over the weekends” (Catalina, 40, one child, aged 6).

Ambivalence About Lone-Parenthood Status

The previous cases point out two important findings: first, there are multiple markers of the transition to lone parenthood that are relevant for parents depending on their parental and relational history; and second, objective markers do not always correspond to the onset of the experience of lone parenting. There is one more set of answers that could not be coded within the two previous groups of cases. For some respondents, it is not possible to univocally define their status as a lone parent or a parent in a couple. On the one hand, they answered our call for interviews with lone parents, but on the other hand, they attached a strong meaning to their relationship with the other parent, who was still perceived as a partner. As a result, they expressed a considerable amount of ambivalence about their own parental status.

Case No. 8

Alexandra (ambivalent relationship with the child’s father): After her divorce, Alexandra met Edouard, a professional who was living with his wife and children. Alexandra moved to be closer to him and continued being his lover, regularly spending holidays with him. Their 13-year secret relationship ended when she became pregnant. She kept the child despite the father initially trying to convince her to have an abortion and refusing to recognize him or see him. After 2 years of separation, Alexandra and Eduard started seeing each other again, and the father started to spend time with his child, introducing him to his official family (Alexandra, on the contrary, did not have access to them until now). She said, “From my side, I have always considered him as my partner and introduced him as such to my family, to my friends, and to others; in his circle, it is rather the opposite … I stay illegitimate, forbidden, etc.” Alexandra lives as a lone parent in her daily life, but at the same time, she is in a sort of living-apart-together relationship with the father of her child and is conscious of the inner contradiction in her situation. “Again, there is a rather fundamental contradiction given that it is not long that I felt ready to live with Edouard, not like a fusion-like couple, but like we had already discussed for years ... we would need a duplex or an apartment with two entries so that we can be separate and together when we want” (Alexandra, 45, one child, aged 3).

Discussion

Lone parenthood is a form of “doing and being” a family. It is sometimes a transitory period in family development and sometimes a long-term experience of parenting alone. This paper draws on qualitative interviews belonging to an ongoing project on lone parenthood in Switzerland. The aim of the paper was to study the ways in which men and women who are raising their children alone narrate their transition to lone parenthood and when they identify the onset of their lone parenthood. By focusing on relational configurations and practices, rather than on economic and residential living arrangements only, this study calls into question the usual assumptions on which most studies on lone parents are based.

We point out at least two limitations of the current practices in quantitative research. First, we show the limitation of residential and administrative criteria to delimit lone-parent status and which are used as bases for current statistics. Lone parents are most often defined as parents residing with at least one child in the absence of the other parent. Variations in such a definition concern the presence of other adults in the household, like a new partner (stepfamilies), other relatives or unrelated adults (multiple generation or enlarged families), or the maximal age of the dependent children present in the household (16, 18, or 25). Alternatively, lone parents are those parents who are financially and legally responsible for the children alone. Such objective definitions are most useful for counting aggregate population data and for having a gross estimation about who is entitled to receive child allowances, child support, and social support. Yet, were our interest as family scientists to be the measuring and modelling of individual lone-parenthood trajectories and understanding their implications as life-course experiences, then we would need to consider subjective markers such as those pointed out by our interviewees in addition to more standard objective indicators. Family surveys, particularly longitudinal perspective surveys, would ideally include measures of social isolation, asking for instance whether the respondent feels to be the only person responsible for their children’s development. Analyses of lone parents’ financial situation would assay respondents to capture retrospectively whether their financial hardships had begun before or after lone parenthood even in cases when individual incomes were unchanged or had increased. Similarly, one could monitor variations in relational quality or in the amount of time that each parent spends with the children. Relational criteria are as important as administrative or residential criteria for identifying whom policies should be addressed to, but they are also crucial for capturing the meaning and effects of lone parenthood in the life course.

Second, our findings call into question the assumption that parental and partnership trajectories evolve simultaneously in the transition to lone parenthood. In fact these trajectories do not always follow the same timing (e.g., Anouk’s case) and this may cause a mismatch in the way lone parenthood is measured and modelled in qualitative and quantitative research. Our interviews show that many current lone parents who were in a couple take some time to end the relationship with the other parent. Cohabitation may not be coincident with a partnership and with coparenting (e.g., in Arthur’s case). These findings suggest the importance of looking at how families “do family” through the meanings they attach to relationships. However, it may also be difficult to describe the status of a relationship. Those who were not in a relationship when a child was born can be ambivalent about their partnership status in relation to the other parent (e.g., in Alexandra’s case). The transition to lone parenthood, particularly lone parenthood as a consequence of separation or divorce (as analysed in this chapter), is often a gradual and ambivalent transition, which involves a variety of dimensions. The fact that it is gradual makes it hard for respondents to identify a date at which it began. The ambivalence makes it hard for them to identify the relevant marker for the transition. In addition, it is not necessarily a unidirectional transition since separation and reconciliations happen without being marked by consequent legal and residential steps. The latter characteristic increases the risk that retrospective data misestimate periods of lone parenthood. The gradual evolution from couple to lone parenthood or from a pregnancy with a potential future partner and coparent to lone parenthood includes some analytic challenges. Demographers have often felt the need to assume that there is a clear distinction between being single and being in a partnership. This is even truer in the case of a pregnancy or a child. However, as we have seen, this is not always the case. What are the consequences and why do we care? For instance, if we were to study lone parenthood together with noncustodial parenthood, we may find mismatches in the declarations of men and women concerning the start of their respective new situations (some may think of themselves as in a partnership and some as already single). These challenges are not unique to lone parenthood and are strictly related to similarly blurred frontiers and definitions of cohabitation and Living Apart Together relationships (Binstock and Thornton 2003; Manning and Smock 2005). By pointing out the complexities associated with studying lone parenthood, we hope to contribute to the field by informing future data collection and empirical analysis of lone parenthood.

Notes

- 1.

These figures refer to the prevalence of lone parents in the population at any given point in time. Yet, if one were to have data from a longitudinal perspective and could calculate the percentage of individuals who have ever been single parents, it certainly would be higher, meaning that this condition is experienced and relevant for a larger share of the population.

- 2.

Similar questions can be asked about the definition of the end of the lone-parenthood state and constitute our next investigation.

- 3.

This is different from the case of France, for instance, where two official definitions exist: one residential statistical definition and one legal administrative definition. The latter is historically related to the creation allocation de parent isolé (isolated parent benefit) introduced in 1976 (Letablier 2011), which assigned social benefits to eligible lone parents. Eligible lone parents are those whose children are not financially supported by the nonresidential parent. The residential definition alone was not appropriate to discriminate those households.

- 4.

A short description of the main characteristics of the cases is included in our sample is in the Appendix.

- 5.

In only two cases were children of preadolescent ages.

- 6.

In one case, after 2 h of interviewing, a respondent asked to withdraw from the study, citing that she could not bear the emotions. This respondent was taken out of the sample.

References

Bastin, S. (2013). Exploring partnership trajectories of single mothers: Sequence analyses using the German family panel. Poster session presented at a meeting of the workshop life course after separation, Berlin, Germany.

Bell, J., Clisby, S., & Stanley, N. (2004). Learning from life: An evaluation of peer education in Lincolnshire. Hull: University of Hull.

Bernardi, L., & Hutter, I. (2007). The anthropological demography of Europe. Demographic Research, 17, 541–566.

Binstock, L. L., & Thornton, A. (2003). Separations, reconciliations and living apart together in cohabiting unions. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 65(2), 432–443.

Bonoli, G. (2005). The politics of the new social policies: Providing coverage against new social risks in mature welfare states. Policy and Politics, 33(3), 431–449.

Chzhen, Y., & Bradshaw, J. (2012). Lone parents, poverty and policy in the European Union. Journal of European Social Policy, 22, 487–506.

Coleman, L., & Cater, S. (2006). ‘Planned’ teenage pregnancy: Perspectives of young women from disadvantaged backgrounds in England. Journal of Youth Studies, 9(5), 593–614.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory method: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13, 3–21.

Dowd, N. (1997). In defense of single-parent families. New York: New York University Press.

Duncan, S. (2007). What’s the problem with teenage parents? And what’s the problem with policy? Critical Social Policy, 27(3), 307–334.

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M. (2011). Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kiernan, K., Land, H., & Lewis, J. (2004). Lone motherhood in twentieth-century Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Lefaucher, N., & Martin, C. (1997). Single mothers in France: Supported mothers and workers. In S. Duncan & R. Edwards (Eds.), Single mothers in an international context: Mothers or workers? (pp. 217–239). London: UCL Press.

Letablier, M. (2011a). La monoparentalité aujourd’hui : Continuités et changements. In E. Ruspini (Ed.), Monoparentalité, homoparentalité, et transparentalité en France et en Italie. Tendances, defies et nouvelles exigencies (pp. 33–68). Paris: Harmattan.

Lopez, V. C. (2013). Children were the age group at the highest risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2011, statistics in focus 4/2013. Luxembourg: Eurostat.

Manning, W., & Smock, P. (2005). Measuring and modeling cohabitation: New perspectives from qualitative data. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 67, 989–1002.

Mosimann, A., & Camenisch, M. (2015). Enquête sur les familles et les générations 2013: Prémiers résultats. Neuchatel: OFS.

Phoenix, A. (1991). Young mothers. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Ragin, C., & Becker, H. (1992). What is a case? Exploring the foundations of social enquiry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Schnor, C. (2013). Pathways to lone parenthood. The effect of partnership duration prior to household formation and parental status on union stability. Poster presentation at a meeting of the Workshop Life Course After Separation, Berlin, Germany.

SmithBattle, L. (2000). The vulnerabilities of teenage mothers: Challenging prevailing assumptions. Advances in Nursing Science, 23(1), 29–40.

Struffolino, E., & Bernardi, L. (2017). Vulnerabilität alleinerziehender Mütter im Laufe des Lebens in der Schweiz. Zeitschrift für Soziologie der Erziehung und Sozialisation, 37(2), 123–141.

Struffolino, E., Bernardi, L., & Voorpostel, M. (2016a). Self-reported health among lone mothers: Do employment and education matter? Population-E, 71(2), 187–214. https://doi.org/10.3917/pope.1602.0187.

Whitehead, M., Burström, B., & Diderichsen, F. (2000). Social policies and the pathways to inequalities in health: A comparative analysis of lone mothers in Britain and Sweden. Social Science Medicine, 50(2), 255–270.

Acknowledgement

This paper benefited from the support of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research LIVES–Overcoming Vulnerability: Life Course Perspectives, which is financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant number: 51NF40-160590).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Annex 1: Respondents’ Profiles at Interview

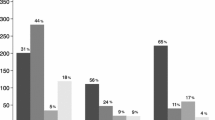

Annex 1: Respondents’ Profiles at Interview

Sample size | 40 |

Average age | 38 |

Sex | |

Male | 2 |

Female | 38 |

Civil status | |

Divorced | 9 |

Male | 1 |

Female | 8 |

Separated | 9 |

Male | 1 |

Female | 8 |

Single | 19 |

Widow | 2 |

Civil partnership (PACS) | 1 |

Entry into lone parenthood | |

LPa after couple | 30 |

Male | 2 |

Female | 28 |

Began as lone parent | 10 |

Number of children | |

1 | 23b |

2 | 15 |

3 | 2 |

Education level c | |

High | 23 |

Low | 17 |

Male | 2 |

Female | 15 |

Income level | |

High | 2 |

Medium | 21 |

Male | 2 |

Female | 19 |

Low | 17 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bernardi, L., Larenza, O. (2018). Variety of Transitions into Lone Parenthood. In: Bernardi, L., Mortelmans, D. (eds) Lone Parenthood in the Life Course. Life Course Research and Social Policies, vol 8. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63295-7_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63295-7_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-63293-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-63295-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)