Abstract

The UK combines one of the highest rates of lone parenthood with one of the lowest rates of maternal employment in the OECD. In this chapter we look at how becoming a lone mother influences women’s economic position using 18 waves of data from the British Household Panel Survey. First, we look at how women’s economic situation is influenced by the transition to first-time motherhood, and second, at the influence of lone motherhood on these outcomes. The outcomes considered are women’s labour market position and household income. We also look at how these demographic transitions influence different income sources. The results suggest that while becoming a first-time mother has a strong influence on employment, with rates of employment and working hours falling substantially upon becoming a mother, lone motherhood has little additional influence. Looking at income, although motherhood leads to a fall in women’s own earnings, within couples these changes are compensated for over time by increases in partners’ earnings and higher child related benefits. For those who become lone mothers, losses in own income combined with the absence of a partner’s income compensating for this loss leads to substantial and sustained falls in income over time.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

A growing body of research links the rise in lone parent families to growing income inequality and poverty (Burtless 1999; Chevan and Stokes 2000; Martin 2006). These studies suggest that changing family structures and in particular the rise in lone parent families accounted for up to two-fifths of the rise in US family income inequality (for a review see McLanahan and Percheski 2008). However, as these studies use cross-sectional data they are not able to tell how well-off lone parent families would have been had they not become lone parents: those that become lone parents have been poor even if they were had not had children, or if they had remained living with a partner.

In this chapter we address the question: to what extent is becoming a lone parent associated with worse economic outcomes for women? We do so by tracking women over a long period of time to see how they are influenced by (i) transitions to motherhood and (ii) partnership status. As authors such as Esping-Andersen (2009) have noted this first transition, the transition to parenthood, and its influence on women’s employment and earnings appears to have an important impact of lone parent’s later outcomes. Yet while a great deal of previous research has examined the effect of motherhood on women’s earnings and employment (e.g. Harkness and Waldfogel 2003) far fewer studies have looked at the subsequent influence that these losses have on lone mothers’ economic outcomes. The economic consequences of partnership status and, of particular relevance here, partnership dissolution, have been much more widely studied. These studies, with few exceptions, find that women, and in particular women with children, face substantial income losses as a result of partnership breakdown (Page and Stevens 2004; Jenkins 2008; Brewer and Nandi 2014).

While partnership breakdown and divorce are important routes into lone parenthood, a large share of those that experience lone motherhood become lone parents because they give birth to a child without co-residing with a partner. These “birth lone mothers” make up a large share of those who ever experience lone parenthood; data from the UK birth cohort studies show, for example, that among children born in 2000 over 40% of those who experienced lone motherhood before the age of 11 were born to a lone mother (Harkness and Salgado 2018). This route into lone parenthood has been much less widely studied than divorce or separation although a few US studies have looked at the economic consequences of becoming a teenage mother (Geronimus and Korenman 1992) or having children out-of-wedlock (Sigle-Rushton and McLanahan 2002), both groups with a high risk of being lone mothers at birth.

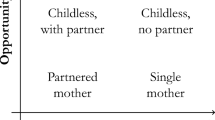

This chapter uses data from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) between 1991 and 2008 to assess the economic consequences of becoming a lone mother. It contributes to the existing literature on lone-parent families in two ways. First, we take a novel approach to assessing the influence of lone motherhood on economic outcomes by tracking individuals over time to see how they are affected both by motherhood and by partnership. Second, the consequences of lone motherhood are considered separately for those that were single at the time of their first child’s birth, and for those that experience later separations. The economic outcomes we consider are labour market outcomes (employment and earnings); household income (gross, net and equivalised); and household income composition.

The rest of the chapter proceeds as follows. In the following section we review the literature on how motherhood and partnership influence women’s economic outcomes. We then describe the UK context. The subsequent sections describe the data and methods, before presenting the results. The final section discusses the implications of our findings and concludes.

Literature Review

In all countries lone mother families face a disproportionately high risk of poverty (Gornick and Jäntti 2007). Here we review the evidence of the effects of parenthood and partnership on women’s economic situation, first looking at the influence that children have on women’s employment, earnings and family incomes and second at the impact of partner absence on these outcomes.

Mothers, whether lone or partnered, face large employment and earnings penalties (see, for example, Harkness and Waldfogel 2003; Harkness 2013). Reasons for this include specialization within the household and reduced work effort (Becker 1985); exchanging jobs for those that are more family friendly (Budig and England 2001); reduced labour market attachment and greater constraints on job choices (Manning 2003), as well as direct discrimination against mothers (Correll et al. 2007). These factors act together to reduce mothers’ earnings. Reduced earnings may in turn lead to women opting-out of the labour market or reducing their working hours, particularly when their children are young and where the costs of childcare are high (Gornick and Jäntti 2010). Because children have a large effect on women’s employment and earnings they also have a substantial influence on families’ disposable incomes, although the size of this effect varies widely across countries. The tax and benefit system also compensates for some of the costs of children, although rarely by a sufficient amount to compensate for losses in female earnings (Todd and Sullivan 2002).

While the arrival of children is associated with reduced female employment and earnings and falls in family income, the absence of a partner can have a substantial additional effect. There is some evidence that marriage matters to women’s earnings, having a negative effect on pay (Loughran and Zissimopoulos 2009), although there is much little evidence on how separation affects labour market outcomes. Instead most studies have looked at the impact of separation on income. Using panel data to follow individuals over time, the literature on relationship breakdown invariably finds that women see large and persistent falls in their income following separation (Jarvis and Jenkins 1999; Fisher and Low 2012; Brewer and Nandi 2014) although being in employment and re-partnering both offer some protection against falling income (Jenkins 2008).

While the loss of a partner leads to a sharp fall in income, recent years have seen a rapid rise in the number of children who born to lone mothers. In the UK, recent analysis of the Millennium Cohort Survey data shows that 11% of all children born in 2000 were born to a lone mother, and of those that experienced lone parenthood before the age of 11, one-third had done so because they were born to a lone mother (Harkness and Salgado 2018). Yet in spite of the importance of birth as a route of entry into lone parenthood very few quantitative studies have examined how having a child while alone influences women’s economic circumstances. One study that does attempt to do so is Page and Stevens (2004). They estimate the “cost” to birth lone parents of not having a partner by seeing how income changes upon re-partnering (although they do not look at the cost of having a child). They find the cost of not having had a partner to be substantial, although they are unable to control for selection effects among those who re-partner which may be important given the positive association between re-partnering and employment and income observed in other studies. Another US study of mothers who had given birth out-of-wedlock concluded that even if both parents had stayed together and had both worked full-time, even under these optimistic conditions, low levels of human capital among the unwed meant that substantial numbers would remain poor (Sigle-Rushton and McLanahan 2002). There are no similar quantitative studies to our knowledge for the UK.

Finally, there is a burgeoning literature on lone mothers which examines how their employment, incomes and poverty rates have been influenced by reforms to the welfare system (Meyer and Rosenbaum 2001; Grogger 2003; Gregg et al. 2009). This literature rarely looks at how the route of entry into lone parenthood influences outcomes, or distinguishes between the influence of motherhood and that of being single for outcomes. Yet there is some reason to expect that this to matter. For example, those that were previously in a relationship may have been more likely to have placed a lower priority on work if they were expecting to be supported by a partner. Those that have children while alone would have fewer expectations of such support and may therefore be more inclined to maintain their labour market position. Other factors matter too. The fathers of mothers that separate are likely, for example, to get greater support from the absent parent, both in terms of maintenance payments but also in the care of their children, which may make it easier to hold down a job. These differences are rarely explored in studies of lone parents.

The UK Context

The UK stands out as having one of the highest rates of lone motherhood and one of the lowest rates of lone mother employment in the OECD, contributing towards high rates of child poverty. This makes the UK a particularly interesting country to study as, although rates of lone parenthood are similar to those in the US (which is where much of the empirical evidence on lone parenthood is drawn from), the institutional and welfare context differs substantially.

In 2011 almost one-in-four children in the UK lived in a lone parent family, one of the highest rates in the OECD (OECD 2014). The rise in the lone parent families is a recent phenomenon, as Fig. 10.1 shows, with the share of families with children that were headed by a lone parent trebling between 1971 and 1995, with a large share of this increase driven by the rise in lone mothers that have never married. Since the 1990s the share of lone parent families stabilized, something that is also reflected in our analysis of the BHPS data which shows little change in the share of mothers who are lone parents between 1991 and 2008.

Share of families with dependent children that are lone parent families by legal marital status (Source: Reproduced from Berrington (2014, p. 5))

High rates of lone motherhood coincide with very low rates of lone parent employment. In 2011 employment rates were among the lowest in the OECD, at around 50% and lone mothers were considerably less likely to work than those who lived with a partner (Fig. 10.2). These differences persisted even after more than a decade of reforms to the British welfare system which had prioritised lone parents’ employment and the introduction of a raft of new policies to provide financial incentives to work (through the introduction of tax credits) and activation policies which aimed to support lone mothers find work. While the generosity of out-of-work benefits for families with children may continue to provide a partial explanation of low rates of employment among lone mothers (OECD 2014), there may be other reasons for low employment rates. First, in the UK, as in the US, lone mothers are “negatively selected”, often being younger and with lower levels of education than mothers with children (Harkness and Salgado 2018). For these younger, less-educated women motherhood is associated with large reductions in employment and earnings (Harkness 2016). These low overall maternal rates among the less educated, rather than benefit levels, may provide an alternative explanation for low employment rates among lone mothers.

Share of lone and partnered mothers (age 15–64) in paid employment, 2011Source: OECD (2014), OECD Family Database, OECD, Paris (www.oecd.org/social/family/database.htm))

Low maternal employment rates have an important effect on families’ income. It is no surprise then, given the large effect that children have on employment rates of mothers that the relative income of families with children in the UK is also among the lowest in the OECD (Fig. 10.3): couples with children have disposable incomes almost one-quarter lower than couples without, while lone mothers average disposable income is just 40% of that of childless couples. Similarly, low employment rates and, for those in work, high rates of part-time work and low wages, mean that a very large share of lone parent families are poor. In 2008 over one-third of lone parent families lived in poverty (DWP 2014).

Relative disposable household income of single parents and couples with children relative to working-age couples without children (Source: OECD Family Database 2014, CO2.1, http://www.oecd.org/els/soc/database.htm)

Data Description

Data from 18 waves of the British Household Panel Survey (1991–2008) is used to track women over time. In each wave the survey reports data from a nationally representative sample of around 10,000 individuals. Households are followed over time, with children joining the main sample once they reach age 16, and new partners of original sample members are also included. The survey is designed to ensure that the sample remains representative of the UK population over time. Later waves also saw the addition of booster samples were for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The main BHPS data files are supplemented by data from ESRC Data Archive study number SN3909, which provides supplementary estimates of net income and some of its components (such as benefit income) which have been constructed using definitions that match those reported in UK official income distribution statistics, as well as a set of variables that classify individuals by family type, and family economic status (Levy and Jenkins 2012).

The main concern of the paper is to examine how motherhood and subsequent (or concurrent) transitions to lone motherhood influence economic outcomes. Only those who are observed to become a mother to a first child are included in the sample. The sample is restricted to those who are aged under-55, so as to exclude those who may be affected retirement decisions. The final sample, summarized in Table 10.1, includes 1431 individuals who become first time mothers, and 15,786 observations. Of these first time mothers 356 are also observed to become lone mothers (3748 observations) with 187 of these lone mothers being observed entering lone motherhood directly as a result of a first birth and 166 entering lone parenthood as a result of separation. Some women are observed to become lone parents more than once. Where this is the case we assess how their economic trajectories are influenced as a result of the first transition to lone parenthood. Among our sample, as shown in Table 10.1, the average length of time over which birth lone mothers are observed following a first birth is 6 years, and they are observed for 3-years before the birth. For those that separate, we observe them for an average of 10-years after a first birth and for an average of 5-years after separation. Those that remain coupled are observed for an average of 11-years and for 7-years with children.

In our sample, more than half of those observed to become lone mothers enter lone parenthood as a result of a first birth. While this share is high, it is consistent with data reported elsewhere (see Harkness et al. ibid.). In our data we observe children until, on average, the age of 7 and so we can expect this share to be higher. It is also worth noting that lone parenthood is a transitory state, and where lone mothers re-partner the new relationships they form are often unstable. Our calculations using BHPS data, not reported hers, show what while at any point in time the share of lone mothers who enter lone parenthood as a result of a child’s birth is around one-if-five, a similar share become lone parents as a result of a breakdown in relationships within step or blended families.

Finally, one concern may be that non-random sample attrition influences our results. Other studies that look at how partnership dissolution influences income using BHPS data find that non-random attrition does not bias their results (Jenkins 2008; Fisher and Low 2012) which provides some reassurance for the results reported here although of course this remains a limitation of this study.

Methods

One of the primary concerns of any study of lone motherhood is to assess how selection into lone parenthood influences observed economic outcomes. Using panel data to follow women over a long period of time helps overcome this problem as we are able to observe how these women were faring both before and after parenthood and lone parenthood. Studies of divorce and separation take a similar approach, using panel data to follow the same individuals’ over time to see how their economic circumstances change as a result of partnership transitions (e.g. Jenkins 2008; Brewer and Nandi 2014; DiPrete 2002; Smock et al. 1999).

The results presented in this study are descriptive and show how employment rates and incomes change for women before and after the birth of a first child and before and after separation. To look at the influence of a first birth on economic outcomes, and to see whether these outcomes are transient or persistent over time, we report outcomes 1-year prior to a first birth, the year of birth, and 1 and 3 years. To look at the association of these outcomes with separation, we similarly look at socio-economic circumstances 1 year prior to separation, the year of separation and 1 and 3 years after. This allows us to assess the separate influence of birth and separation on the economic circumstances of lone mothers.

The socio-economic circumstances we look at are the shares in employment, full-time employment, that are homeowners and who live with their parents as well as hourly wages and income. The measures of income reported are gross, net and equivalised income (using the modified OECD scale). We also report components of income. Parenthood and lone parenthood may influence not only the earnings of women and, where present, their partners, but also their influence benefit receipt. We report descriptive data to show how women’s earnings, (where present) spouse’s earnings, transfer income and benefits change around transitions to parenthood and lone parenthood. All monetary values are deflated to January 2010 prices. We trim household income data at 1% to avoid including negative or zero incomes, and to avoid problems of top coding. Finally, to adjust income for needs we use the modified OECD equivalence scale which give the first adult a weight of 1, each person age 14 or over a weight of 0.5 and each child under 14 a weight of 0.3.

Throughout, lone mothers who separate and those who become lone mothers as a result of a first birth are considered separately, and their incomes are compared to those of families where children continue to live with both biological parents. This allows us to get a sense of the importance of prior economic circumstances for the observed poor economic circumstances of lone mothers.

Lone Mothers in the UK: Characteristics, Employment and Income

The US literature has described the “diverging destinies” of children being brought up in lone parent families and those living with both biological parents (McLanahan 2004). Over recent decades, she argues, the resources (in terms of parental inputs and income) available to those growing up in these different family types have diverged with lone parenthood becoming increasingly concentrated among the less educated. Table 10.2 shows a similar picture for the UK, lone mothers being on average younger at the time of first birth and holding fewer qualifications than mothers who live with a partner. Most studies of lone parents look only at characteristics of lone mothers observed at a particular point in time and do not distinguish lone mothers by their route of entry to lone parenthood. Looking only at those who become lone mothers over the period of study, reported in Table 10.2, we see large differences between lone mothers that separate and those that become lone mothers by birth: while those that separate have lower levels of education, are on average younger at the time of becoming a first time parent and are more likely to be home owners or live with their parents than those in couples. The differences between those who separate and who become lone mothers by birth are larger again. For example, one-third of birth lone mothers were homeowners compared to 51% of those that separated and over 80% of those in couples. One-quarter lived with their own parents compared to just 6% of separating lone mothers and 1% of couples. The average age at the time of a first birth among birth lone mothers is 24, compared to 27 for those who separate and 29 years among those who remain partnered. However, there is a large degree of heterogeneity among birth lone mothers in particular. While birth lone mothers are particularly likely to be young and hold no qualifications, there are also a fairly large number of women who are older at the time of a first birth (one-in-five birth lone parents had their first child after the age of 35) and 10% had degrees. Comparing all lone and partnered mothers to the sub-samples that are observed before the birth of their first child in Table 10.2 shows strong similarities between the full and restricted samples.

As in the US then, lone mothers in the UK have lower levels of human capital than mothers that remain in couples. This is reflected in their labour market outcomes and incomes, reported in Table 10.3. Average employment rates of lone mothers stand at around 50%, compared with 65% among mothers in couples, while weekly earnings (which exclude those with no earnings) are almost 30% lower. These aggregate figure again disguises large discrepancies between those who were birth lone mothers and those that separated after having a first child. In particular, separated lone mothers have employment rates similar to partnered mothers, at 64%. In contrast only 38% of birth lone mothers were employed. Earned income is also much lower for birth lone mothers; so while those that separated have weekly wages around 10% lower than partnered mothers, at £185 per week compared to £205, the earnings of birth lone mothers were only just over half the earnings of those that separated at £106. Yet, in spite of these differences in the labour market outcomes of birth and separating lone mothers, income differences were much smaller. Average needs adjusted, or equivalised, incomes for mothers in couples were £319 a week compared to £226 in separated lone mother families and £203 in birth lone mother families. The distribution of equivalised income in lone mother families, and mothers in couples is shown in Fig. 10.4. Even after adjusting for family size lone mothers’ incomes fall far below those of mothers in couples, and their incomes are strongly clustered at the bottom of the income distribution: only a very small number of lone mothers have incomes higher than the median income of couples with children.

Trajectories Over Time: Changes in Economic Outcomes

The labour market outcomes and income data reported in Table 10.3 show lone mothers do badly. These are at least in part likely to be due to the relatively poor characteristics of these mothers. However, they may also be a result of having become a lone mother, whether by birth or separation. To examine the extent to which this is the case we look at how well these women were faring before becoming mothers and lone mothers.

Table 10.4 shows how labour market outcomes changed around two critical points (i) becoming a first time mother, and (ii) following the dissolution of a partnership. Rates are reported for any employment and being in full-time work (30+ hours) and for three groups; mothers who remain with their partner after birth; those that separate and those who were single at the first birth. The first thing to stand out from this table is the large difference in employment rates that existed prior to becoming a mother. Only 63% of birth lone mothers were working prior to a first birth compared to 76% of those who later separated and 87% of those who remained partnered. Differences between those that become lone mothers and those that do not therefore appear to account for large differences in employment outcomes. Second, employment drops much more sharply for those that go on to become lone mothers in the years just after a first birth: while for partnered women employment rates were 18 percentage points lower after a first birth than they had been the year before, the drop was 29 percentage points for both separating and birth lone mothers. For both these groups employment rates recovered 3-years after the birth.

We find separation to have very little association with employment rates. In the year preceding separation 57% of women were in work, and this fell by less than 1% in the year of separation. Employment rates then began to recover and three years after separation were 9 percentage points higher than they had been before the split. For full-time employment, we observe a sharp drop in employment following a first birth with only one-quarter of women who remained living with the child’s father in full-time work three years later and with the share among those that went on to become lone mothers far lower. Separation had little influence on full-time employment rates.

Of course, becoming a mother and a lone mother may also be associated with other changes in living arrangements. Table 10.5 shows how living arrangements changed before and after having children and becoming a lone parent. In particular, we look at changes in homeownership, co-residence with own parents; and re-partnering. Those that become lone mothers are much less likely to be in owner-occupied accommodation in the year before becoming a first time parent. Among those that do not separate, around 80% are home owners the year before a first birth and this share rises slowly with time. Only a very small share live with their own parents at the time of their first child’s birth (6% the year before a first birth and less than 1% three years after). Among those families that going on to separate, just under 3-in-5 are home owners at the time of the first child’s birth. These women are also likely to be living with their own parents in the year preceding a birth (1-in-5 mothers), and at the point of separation almost 1-in-10 live with their parents. Those that have children while alone are least likely to be in owner occupied accommodation and are most likely to live with their own parents – around half live with their parents at the time of birth and while this declines over time the share co-residing with their parents remains high, at 1-in-6 three years after a first birth. Finally, around 1-in-10 lone mothers re-partner within a year of birth (for birth lone mothers) or separation, while around one-quarter have re-partnered within three years.

Figure 10.5 looks at how transitions to motherhood and lone parenthood affect income. It illustrates how the income distribution shifts before and after having a first child, and before and after separation. Panel (a) shows how income changes before and after childbirth for those who remain in couples. For this group the income distribution shifts to the left following a first birth with a further fall in income three years’ post-birth. Birth lone mothers (Fig. 10.5, panel (b)) have much lower levels of income before a first birth, and while we see a similar leftward shift in the distribution of income following a birth this shift is less marked than that for those in couples. Those that separate have more dispersed incomes than either of the other two groups prior to a first birth. A first birth again leads to a left-ward shift in the income distribution, with the post first-birth distribution resembling that for those mothers who remain in couples. The association with subsequent separations is shown in panel (d). Most notable here is that while income declines following a split across the distribution, the influence on income of separation is smaller than that of having a first child, particularly when we observe income 3 years after the split.

Income before and after children and before and after separation. (a) Remain in couples. (b) Birth lone mothers. (c) Separating mothers: change following motherhood. (d) Changes following separation (Notes: as Table 10.4)

Table 10.6 shows which income components drive the overall change in income. For partnered families, mothers’ labour income drops substantially following a first birth and continues to decline over the following three years, partly as a result of changes in employment, partly because of changes in working hours (in particular the switch to part-time work), and partly as a result of reduced hourly wages. On average mothers’ labour market earnings fall by around one-third three years after a first birth. However, within couples, losses in women’s earnings around childbirth are to some extent offset by increases in their partners’ earnings. In row (2) of Table 10.6 (i) the sum of both partners’ earnings is reported. The combined earnings of couples, while showing a small dip around the years of childbirth, recover to a level very similar to their pre-birth levels within three years. In row 3 transfers are added to earned income (row 2). As couples with children receive low levels of transfer income this does not lead to a substantial change. Row 4 adds other income, which includes income from savings and pensions and other household members’ income. Income from these sources falls too around the time of a first child’s birth, further squeezing incomes. Compensating for these losses however are transfers through the benefit system (row 5). Household benefits, including child related benefits, offset the losses in private income which result from having children. These increases in benefit receipt, together with increased male earnings, mean that the overall influence on gross income of having a first child is roughly neutral. The change in net income is similarly neutral (column 6). Finally, after adjusting for needs, in column 7, equivalised income shows a fall of up to 25% in the years following a first birth with no recovery over the next three years that we observe them for. Among mothers in couples therefore we see sharp falls in own earnings following a first birth but that these losses are to some extent offset by increases in the earnings of their partners and by increases in benefit income.

Next we investigate how the experience of those that become lone mothers differs to those who remain in couples. In panel (ii) of Table 10.6 income changes are shown for birth lone mothers. Among this group, average earnings are much lower before childbirth than the mothers who remain in couples, at £163 per week compared to £309 for partnered mothers. And for these women earnings also fall, by around one-third three years after a first birth, following childbirth. These fall leads to an overall drop in family earnings (row 2), although this loss is slightly lower than that reported in row 1 because some birth lone mothers re-partner. Transfer income (row 3), including maintenance, is also low among this group and does little to compensate for losses in earned income. Other household income, and in particular other household members’ earnings, are a particularly important income source for birth lone mother in the years before and after a first birth (row 4), as is household benefit income (row 5). However, over time as birth mothers establish their own homes there are sharp drops in other family members’ income. These losses, together with falls in their own labour income, lead to substantial falls in gross income. To some extent these losses in gross income are compensated for through the tax system (row 6), and changes in family structure as women set up their own households reduces income needs. As a result, overall needs adjusted, or equivalised, income falls by around 20% on becoming a birth lone mother and remains at this level in the subsequent year.

The final panel of Table 10.6 (iii) show income changes for our second group of lone mothers; those that become lone mothers by separation. For this group earnings, while higher than those among birth lone mothers, are lower than for those in couples that remain together and fall by a similar magnitude following a first birth. Following separation earning begin to increase slowly, contrasting with the experience of those that remain in couples whose own earnings decline with time. In row 2 the total earnings of mothers and their partner are reported and again this shows a decline in the couples’ earnings following a birth, but that at the point of separation couples’ income was higher than it had been prior to the first birth. Separation is associated with substantial losses in earned income because of the fall in spouses’ earned income. Transfers, including maintenance payments, play only a very minor role in offsetting these losses. Row 4 also shows a decline in income resulting from other family income which may reflect changes in living arrangements with time. Finally, benefit income has an important impact on reducing the income losses associated with both motherhood and lone parenthood. As a result, for those that separate, motherhood leads to an overall fall in gross household income of around 10%. This recovers to its earlier levels by the year before separation, largely because of gains in partners’ income and in benefit receipt. Separation leads to large further losses in gross income with gross income halving in the years before and after separation largely because of loss partners’ earnings although there is some additional compensation through the benefit system and increased own earnings reduce this gap with time. Net income also falls around separation (row 6). However, adjusting for needs in row 7 we find that having a first child reduced income by almost 20%, although there is some recovery before separation. At the point of separation equivalised income falls again, by a magnitude only slightly larger than that following the arrival of having a first child.

Finally, comparing the incomes of those that enter lone parenthood as a result of a first birth while single and those that become lone parents through separation, we find that incomes are almost identical for these two groups once they become lone parents. This is in spite of the fact that those that separate have higher incomes before having children, and that upon become lone mothers have higher own labour income and receive more income from transfer payments.

Discussion and Conclusion

Lone parenthood in the UK is common and strongly associated with low income. The analysis that we present here suggests that differences in lone mothers and those who are partnered partly result from differences in selection. As the descriptive statistics showed, lone mothers, whether they enter lone motherhood as result of separation or through the birth of a first child while alone, are on average younger at the time of a first birth and less educated than those who are never observed as lone mothers. Levels of human capital among birth lone mothers are particularly low. Even before the birth of a first child, rates of employment and earnings of both groups are far lower than those of mothers never observed to be lone parents.

In addition, partnership and parenthood matter. Becoming a first time mother imposes a substantial economic cost on women and families, reducing their labour force participation, hours of work (with many women switching to part-time employment), and wages. The association of becoming a first time mother with the employment rates and earnings of those that also become lone mothers are of a similar magnitude to those for women in couples that remain together. Our analysis therefore questions the idea that low employment rates among lone mothers in the UK are driven by high levels of benefit receipt (OECD 2014). Instead, we find no indication of differences in the labour market behaviour of those that become lone mothers and those that do not: lone mothers respond in a similar fashion to other mothers following the birth of a first child. The low employment rates among lone mothers instead appear to reflect first “selection” into lone parenthood – those that become lone mothers had low employment rates even before they became parents; and second the large negative influence that parenthood has on maternal employment among all mothers in the UK.

Parenthood also has a substantial influence on income. Even among those that remain in couples we see falls in equivalised income, of up to 25% immediately following a first birth. This loss is largely driven by reduced maternal income and increased family size, although this is compensated for by increases in the earnings of male partners and increases in benefit receipt (including child benefit). For those that become birth lone mothers, mothers’ earnings similarly fall. For this group however there is no male partner to compensate for the loss in mothers’ earnings by increasing their labour supply. Nor do this group receive significant income in the form of transfer payments, including maintenance. This group are instead particularly likely to live with other family members, in particular their own parents, and the earnings of these other household members make up a very important source of income, alongside benefit receipt, in the years before and after a first birth.

Mothers that separate, while having lower levels of human capital, employment and earnings than those that remain in couples, start off with higher levels of income and earnings than those that become lone parents by birth. They are also much more likely to be living independently of their parents at the time they have a first child. On becoming mothers this group too face large falls in their earnings, although becoming a lone parent is associated with slight increases in mothers’ earnings. For these women transfer income, including maintenance payments, and benefits are important sources of income following separation. However, upon becoming a lone mother the economic situation of these women converges to become very similar to that of birth lone parents (Fig. 10.5) in spite of their earlier economic advantage and higher levels of earned income and maintenance payments.

The results reported in this study are descriptive and, while they follow women over time, they do not directly account for the effect of differences in characteristics on observed outcomes. In addition, they do not take account of unobservable differences between lone mothers and those with partners that influence “selection” into lone parent or employment. Nonetheless, in spite of these limitations, they indicate that the poor economic circumstances of lone mothers are likely to be only partially driven by the transition to lone parenthood.

Overall we have shown that for all families there is a high economic cost attached to motherhood in the UK. The results reported here echo those of Todd and Sullivan (2002) who find families with children to have significantly lower disposable incomes than those without in the UK. The difference in incomes of families with children and those without is, they argue, largely a result of the effect that children have on women’s employment. They show that in countries where mothers remain in work after having children families fare better economically: in countries including the US and Scandinavian countries incomes are actually higher among families with children. Other studies similarly show that high rates of female employment are associated with reduced levels of income inequality (Harkness 2013).

Esping-Andersen (2009) argues that in countries where rates of employment are high among mothers’ rates of family poverty tend to be low, particularly because the rate of lone parent poverty falls. For the UK we have shown that falling female earnings following a first birth accounts for around half of the income loss associated with becoming a lone mother among those that separate, with subsequent partnership dissolutions lead to further falls in income of a similar magnitude. Maintaining the earnings position of women at the same level that they had prior to having children would considerably improve the income of all lone mothers. Other studies suggest that this matters not only in the short term; as Brewer et al. (2012) note “family income during the main child-bearing years is an especially good predictor of lifetime income as the consequence of permanent differences in productivity and marriage prospects can be more visible at a time when working is particularly costly” (p. 36).

In the UK many women, and in particular those with lower levels of education, find it hard to sustain employment, and in particular full-time employment, following the birth of a first child. For these women the earnings of a partner are a critical source of income. Yet it is these women, who have the weakest attachment to the labour market, that are also at greatest risk of becoming lone mothers (Gregg et al. 2015). This combined risk of non-employment and lone parenthood means that for many mothers the risk of poverty and low income are likely to continue to remain very high.

References

Becker, G. (1985). Human capital, effort, and the sexual division of labor. Journal of Labor Economics, 3(1, Part 2), 33–58.

Berrington, A. (2014). The changing demography of lone parenthood in the UK (ESRC Centre for Population Change Working Paper Number 48).

Brewer, M., & Nandi, A. (2014). Partnership dissolution: How does it affect income, employment and well-being? (Institute for Social and Economic Research (ISER) Working Paper 2014).

Brewer, M., Dias, M., & Shaw, J. (2012). Lifetime inequality and redistribution (IFS Working Paper 12/23).

Budig, M. J., & England, P. (2001). The wage penalty for motherhood. American Sociological Review, 66(2), 204–225.

Burtless, G. (1999). Effects of growing wage disparities and changing family composition on the US income distribution. European Economic Review, 43(4), 853–865.

Chevan, A., & Stokes, R. (2000). Growth in family income inequality, 1970–1990: Industrial restructuring and demographic change. Demography, 37(3), 365–380.

Correll, S. J., Benard, S., & Paik, I. (2007). Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology, 112(5), 1297–1338.

DiPrete, T. A. (2002). Life course risks, mobility regimes, and mobility consequences: A comparison of Sweden, Germany, and the United States. American Journal of Sociology, 108(2), 267–309.

DWP. (2014). Households below average income 1994/95 to 2012/13. London: HMSO.

Esping-Andersen, G. (2009). The incomplete revolution: Adapting to women’s new roles. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Fisher, H., & Low, H. (2012). Financial implications of relationship breakdown: Does marriage matter? (IFS Working Papers W12/17).

Geronimus, A. T., & Korenman, S. (1992). The socioeconomic consequences of teen childbearing reconsidered. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(4), 1187–1214.

Gornick, J., & Jäntti, M. (2007). Women, poverty, and social policy regimes: A cross-national analysis. In P. Saunders & R. Sainsbury (Eds.), Social security, poverty and social exclusion in rich and poorer countries (pp. 63–96). Antwerp: Intersentia.

Gornick, J. C., & Jäntti, M. (2010). Women, poverty, and social policy regimes: A cross-national analysis (No. 534, LIS Working Paper Series).

Gregg, P., Harkness, S., & Smith, S. (2009). Welfare reform and lone parents in the UK. The Economic Journal, 119(535), F38–F65.

Gregg, P., Harkness, S., & Salgado, M. (2015). The changing nature of lone parenthood and its consequences for children, University of Bath.

Grogger, J. (2003). The Effects of time limits, the EITC, and other policy changes on welfare use, work, and income among Female-Headed families. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85(2), 394–408.

Harkness, S. (2013). Women’s employment and household income inequality. In M. Jäntti & J. Gornick (Eds.), Income inequality: Economic disparities and the middle class in affluent countries. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Harkness, S., & Waldfogel, J. (2003). The family gap in pay: Evidence from seven industrialized countries. Research in Labor Economics, 22, 369–414.

Harkness, S. E. (2016). The effect of motherhood and lone motherhood on the employment and earnings of British women: A lifecycle approach. European Sociological Review, 32(6), 850–863.

Harkness, S. E., & Salgado, M. (2018, forthcoming). Children’s Emotional development and educational attainment in single mother families in the UK. In R. Nieuwenhuis & L. Moldano (Eds.), The triple bind of single parents. Bristol: Policy Press.

Jarvis, S., & Jenkins, S. P. (1999). Marital splits and income changes: Evidence from the British household panel survey. Population Studies, 53(2), 237–254.

Jenkins, S. P. (2008). Marital splits and income changes over the longer term (Institute for Social and Economic Research Working Paper No. 2008–07).

Levy, H., & Jenkins, S. P. (2012). Documentation for derived current and annual net household income variables, BHPS waves 1–18. Manchester: ESDS.

Loughran, D. S., & Zissimopoulos, J. M. (2009). Why wait? The effect of marriage and childbearing on the wages of men and women. Journal of Human Resources, 44(2), 326–349.

Manning, A. (2003). Monopsony in motion: Imperfect competition in labor markets. Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Martin, M. A. (2006). Family structure and income inequality in families with children, 1976 to 2000. Demography, 43(3), 421–445.

McLanahan, S. (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41(4), 607–627.

McLanahan, S., & Percheski, C. (2008). Family structure and the reproduction of inequalities. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 257–276.

Meyer, B. D., & Rosenbaum, D. T. (2001). Welfare, the earned income tax credit, and the labor supply of single mothers. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(3), 1063–1114.

OECD. (2014). Family database. Paris: OECD.

Page, M. E., & Stevens, A. H. (2004). The economic consequences of absent parents. Journal of Human Resources, 39(1), 80–107.

Sigle-Rushton, W., & McLanahan, S. (2002). The living arrangements of new unmarried mothers. Demography, 39(3), 415–433.

Smock, P. J., Manning, W. D., & Gupta, S. (1999). The effect of marriage and divorce on women’s economic well-being. American Sociological Review, 64, 794–812.

Todd, E., & Sullivan, D. (2002). Children and household income packages: A cross-national analysis. American Economic Review, 92, 359–362.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Economic and Social Research Council for supporting this research under grant number ES/K003984/1.

This paper benefited from the support of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research LIVES–Overcoming Vulnerability: Life Course Perspectives, which is financed by the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant number: 51NF40-160590).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Harkness, S. (2018). The Economic Consequences of Becoming a Lone Mother. In: Bernardi, L., Mortelmans, D. (eds) Lone Parenthood in the Life Course. Life Course Research and Social Policies, vol 8. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63295-7_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63295-7_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-63293-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-63295-7

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)