Abstract

Legal and philosophical accounts of ‘the will’ seem insufficient when thinking about what residents of nursing homes dementia want, and how situations in which a resident wants something else than his or her care worker should be dealt with. In this chapter, I offer an alternative understanding of the will—namely as ‘done’ in sociomaterial interaction, in which it can be aligned by making it relational. Instead of dismissing ‘daily wanting’ of those living with dementia, my analysis enables thinking about it. Based on an ethnography of daily care situations in physical care provision in Dutch nursing homes for people with dementia, I propose the concept of ‘sociomaterial will-work’ to highlight how daily wanting is worked upon in the context of unfolding sociomaterial interaction. I describe ways in which care workers’ and residents’ attempt to align the other’s wanting with their own as a form of labour and as dependent on sociomaterial relations, namely by (1) sculpting moods and emotions, (2) managing attention and (3) creative negotiation involving time and materialities. I argue that we may learn something about good care from taking a closer look at these practices: in doing sociomaterial will-work care workers strive for a positive way of relating, seeking alternatives to nothing for neglecting the resident or exerting force. Indeed, sociomaterial will-work may sometimes fail, but, as is key to doing good care, even so, it keeps on trying.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

‘Daily Wanting’ in Dementia Care

Then,Footnote 1 finally, Ella VeenstraFootnote 2 gets out of bed, and walks to her bathroom. Ella, as her care workers affectively call her, is living with Alzheimer’s disease in a Dutch sub-urban care home called ‘Zonneweide’.Footnote 3 She moved here six years ago, when she was no longer able to manage by herself. That Ms Veenstra gets up in the morning is the result of a lot of work on the part of her care workers. Every day anew, when asked to get up, she insists on staying in bed, stating that she has a headache. Indeed, Ms Veenstra is known to have had migraines for most of her life and is given a light pain killer every morning and ‘more if necessary’. However, so her care workers tell me, her headaches ‘may have become a bit of an excuse to not get up’. Her caregivers check her perspiration and her eyes to determine when she ‘really’ has a headache. When the care worker on duty thinks she does not, sheFootnote 4 starts to encourage Ms Veenstra to get up, acting on the team’s agreement that it is best for Ms Veenstra to get out of bed: once she is up, she eats with the other residents and forgets about wanting to stay in bed. Sometimes Ms Veenstra goes back to bed after breakfast, and her care givers agree that doing so should be allowed. In talking about situations like getting Ella up, care worker Anja tells me: ‘This is the difficulty with care work, especially with people with dementia.’ She gives me other examples: ‘[Another resident] always says “Let me stay in bed, let me stay in bed”. […] But she eats better when she is up—then she sits upright; she drinks better; she reads a paper and participates in activities. Then one sees that getting up has an added value. With people with dementia you typically have to make choices for them, because they cannot do that anymore.’ I push the conversation: ‘But they do make a choice, only not the one that is right in your eyes.’ Anja retorts: ‘I could follow [her] choice, but then I know I am not providing good care. […].’ I ask: ‘So it is about good care?’ upon which Anja answers: ‘Yes, good care is the basis. Taking one shower per week is really the minimum. There is another lady who has a trauma from showering because she once stood under boiling hot water. In that case, she really does not have to shower; I’ll wash her instead. […] I would not coerce her to get into the shower.’

These stories are examples of situations that many caregivers working in dementia care homes will recognise immediately: the resident wants something that the care worker thinks is not good for her. In other words, what a resident wants (here, to stay in bed) does not always align with what the caregiver wants (here, if the resident does not seem to have a migraine, to get the resident up, and, ideally, for the resident to want this as well).Footnote 5

While the tension between opposing desires is certainly not unique to dementia care, it is characteristic for care encounters with those living with decreasing mental capacities. With the progression of the dementia, the person living with the condition requires increasing levels of assistance to complete everyday bodily tasks: she will need more help with getting up and being washed and dressed. Some people simultaneously lose their awareness of the need to get up and keep clean. Although staying in bed and refraining from washing is possible for some days, doing so for longer may come to harm one’s health and well-being. Therefore, accomplishing the tasks of getting residents up and washed falls to care workers . This sometimes results in situations in which residents refuse to get up, do not want a shower or want to wear their favourite shirt while their care worker finds it too dirty to wear.Footnote 6 Studies on care work have pointed out that care workers often call residents who do not want the same as themselves in activities of daily living (ADL) care encounters ‘difficult’ or exhibiting ‘challenging behaviour’ (e.g. Higgs and Gilleard 2015, pp. 89–90). But they frequently stop short at unpacking how this encounter plays out when it presents itself.

To want something is an expression of subjectivity, and being respected in one’s desires is as much part of living a good life in a dementia care home as it is elsewhere. But how can we think about what residents want in cases which lead their care workers to assert that what a resident wants is not good for her? Indeed, if care were just about ‘getting the job done’ then the way it is done would not be relevant. In practice, however, this clearly matters. As care worker Cici remarked: ‘As a normal human being you do not want to be forced all the time!’ Similarly, one may not want to be left to one’s fate all alone either. Indeed, there is a lot in between.

This is not to say that coercion or neglect never happens in care work. When Ms Lichthart woke up covered in her own faeces, but was nevertheless resisting a shower, two care workers held her in a tight grip while another washed her quickly. It seemed ‘the only way to do this’. Ms Lichthart indeed needed a shower, but by washing her this way, what she wanted was overruled. Yet, rather than concluding that ‘things are not going well in care’ because these situations do occur, I want to emphasise here that such generalisations about care work miss something: they miss the work that care workers do on a daily basis to prevent these extreme measures. This work becomes most visible in situations in which what a resident wants is opposed to what a care worker wants.

Debates on the will are an obvious starting point to take a closer look at these situations. Thinking about the will has long been the domain of philosophers. In the most general sense, philosophers have understood the will as the ‘“faculty, or set of abilities, that yields the mental events involved in volition”, where volition is understood to be “a mental event in the initiation of action”’ (Brand 1995, p. 843 in Murphy and Throop 2010, p. 7). Debates on the topic have focused on the (in)compatibility of relative freedom and determinacy of human choice and action. Within these debates, moral philosophers attach particular value to the free will. After all, whether, or to what extent, we can act freely informs whether we have a choice to act in a good or bad way in the first place. Put differently, without a will that is free (at least to some degree), moral decision making is not possible.

Dementia care presents an interesting case to think about ‘the will’, as dementia is usually said to invalidate it altogether. For instance, Dutch law uses the term ‘wilsonbekwaam’ (which translates freely to ‘will-incompetent’Footnote 7) for those who are unable to understand or deliberate on information that is provided to them, who cannot make a decision and/or who no longer understand the consequences of their decisions (Rijksoverheid 2014). This legal category dismisses the person’s will, making possible, for example, a person’s admission to a nursing home against her will.Footnote 8

The philosophical and legal accounts both reflect an understanding of the will as related to cognition and rationality. This understanding may be useful with regard to long-term decision making (which indeed becomes increasingly difficult for people with dementia with the progression of the condition). However, it is less helpful with regard to the ‘daily wanting’ on the dementia ward. Indeed, a lot is wanted on the dementia ward! How may we think about those situations?

Much anthropological writing can be read as a critique of the rational understanding of ‘the will’. In using concepts such as agency, intentionality, motive, desire, wish and motivation, anthropologists are perhaps only implicitly speaking about the will, but nevertheless bring to light a complex interweaving with emotional and physical states. This literature provides a helpful background against which to rethink the will in relation to dementia and dementia care, and situations in which residents want something different than their caregivers want for them in particular. However, this body of work lacks a definitional consensus and thus a common ground for discussion. In their edited volume ‘Toward an Anthropology of the Will’, Keith Murphy and Jason Throop (2010) make considerable steps towards such a consensus. In his contribution to the volume, Jason Throop argues that the will is experienced as somehow one’s own, goal-directed and effortful (2010, p. 34). While this is important when thinking about why what somebody wants cannot be simply overruled, Throop is right in suggesting that there is still

a necessity of shifting from this descriptive phenomenological approach to willing to exploring how these various experiential correlates of willing may be differently organized, affected and expressed in the context of unfolding social interaction, personal narratives, and reflections upon past, present and future experiences. (Throop 2010, p. 49)

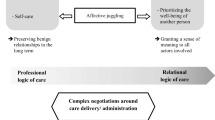

In this chapter, I take up Throop’s invitation to think further about ‘willing’ in interaction. However, as I discuss in more detail in the following paragraph, I focus on ‘daily wanting’ instead of willing, as it is worked upon in the context of unfolding sociomaterial interaction. Moreover, I ask what we may learn about good care from taking a closer look at these practices. Based on my ethnography Footnote 9 of ADL-care situations in which residents with dementia often want something other than what their caregivers think is good for them, I argue that, rather than coercing residents into doing whatever task is at hand, care workers attempt to align what residents’ want with what they themselves want (for them). I propose the concept of ‘sociomaterial will-work’ to describe this work and reflect on its limits and implications. At the same time caregivers may come to want something else too; will-work can thus align the wanting of residents but also of their caregivers.

Work on Wanting: Sociomaterial Will-Work

Before going into the ethnography of ADL encounters in which wanting is aligned, I want to highlight two methodological interventions that I make with this chapter. Firstly, I contend that the term ‘will’ suggests a coherence that hides the relational nature of coming to want something. I therefore suggest that, rather than understanding the will as something we ‘have’, we should understand it as something we ‘do’ in unfolding sociomaterial interaction. Secondly, since my interest here is in understanding the alignment that is strived for in the process of wanting in dementia care settings on a daily basis, I differentiate between ‘willing’ and ‘wanting’. I separate a more cognitive intending, pertaining to the realm of the legal and long-term decision making (‘willing’), from a more immediate, emotionally and physically informed activity (‘wanting’). I understand wantingFootnote 10 to be a fundamental expression of subjectivity, including activities such as desiring, longing, wishing and, significantly, not wanting, which is done in unfolding sociomaterial interaction on an everyday basis.

In defining the will as something we do in sociomaterial interaction, I align myself with the tradition of material semiotics, in which practices take central stage (Law 2009). I put my writings in conversation with the work on care practices (e.g. Jerak-Zuiderent 2015; Mol 2002; 2008; Mol et al. 2010; Moser 2010a, b; Van Hout et al. 2015; Vogel 2017). Within this tradition, I have been particularly inspired by the work of Jeannette Pols with patients in psychiatric and residential care. She draws our attention to the fact that residents of psychiatric nursing homes , rather than saying what they like, make their appreciations known by enacting them (Pols 2005). Positing that appreciations can be enacted means that they can be expressed both verbally as well as non-verbally. Any interaction may thus include gestures, facial expressions and actions. This is important when thinking about dementia, as most nursing home residents—whether aphasic, passive, confused or hallucinating—can and do express whether they want something or not. They may do so by softly uttering a ‘yes’, seeking company or trying to escape it, pushing their plate away or, indeed, by not heeding the call to get out of bed. This has a crucial methodological consequence: as residents do appreciations in situations that are co-produced by the material environment and other people, they may be observed.Footnote 11

If wanting is done, as I suggest, in unfolding sociomaterial interaction, how it is then acted upon is almost inevitably an ethical and political question. As I have mentioned before, wanting is an essential expression of subjectivity, and is thus best respected and stimulated. Indeed, avoiding coercion was central to many conversations I had with care workers . They commonly held the understanding that in order to get residents to ‘cooperate’ [meewerken], ‘urging [aandringen] is allowed, but coercing [dwingen] is not’.Footnote 12 Care workers also told me time and again that ‘[i]f a resident really does not want to do something, then she does not have to do it’. The distinction that is made between ‘what a resident wants’ and ‘what a resident really wants’ is an interesting one. Indeed, the word really indicates that what is wanted is—at least to some degree—flexible. It is this flexibility that is used to ‘urge’ residents. The exchange with Anja makes this visible: while she says she makes decisions for residents, she adapts her way of providing care to them, and what they ‘really’ want, or do not want. She thus strives to complete ADL-care without coercion or neglect: the resident who is traumatised from standing under boiling water does not have to shower, and Anja washes her by the sink instead. Indeed, care workers tried to negotiate with residents if they did not want to do a task the care givers asserted needed to be done. Care workers also often proved flexible in showering residents at another point in time and giving in to residents who, for instance, insisted on wearing certain clothes.

I propose to call the practices in which residents and care workers seek to (creatively) align what they both want ‘sociomaterial will-work’.Footnote 13 , Footnote 14 I am indebted to three bodies of work for the concept. First, my choice of the word ‘sociomaterial’ builds on the material semiotic tradition. Herein, social and material ‘aspects’, previously separated in social sciences, ‘get mixed up in ethnographic descriptions of the practices in which they are being handled’ (Harbers et al. 2002, p. 208). Second, my choice for the word ‘work’ relies on theories of (interpersonal) body work (Gimlin 2007; Twigg et al. 2011; Twigg 2000; Wolkowitz 2002), emotional labour (Hochschild 1979, 1983) and sentimental work (Strauss et al. 1982). This literature emphasises the dual nature of these types of work (largely organised as ‘women’s work’) as both a loving attitude and a form of (paid) labour. This insight informs the concept of will-work in significant ways: will-work is work; it takes time, effort, and skills, and it is a central aspect of care giving, which requires an attentive caregiver. The types of work described above and will-work can be highly entangled. Acknowledging this adds to a more complex understanding of what giving care to people with dementia entails. Third, the concept of will-work rests on the shoulders of feminist care ethicists (e.g. Gilligan 1982; Tronto 1993), who have advocated for an acknowledgement of peoples’ dependence and interdependency on one another. Will-work is a deeply relational practice: in doing will-work care workers rely on relational knowledge, acquired in their everyday work with the same people, often for the duration of years. In the unfolding interactions, resident and care worker relate to one another. Care ethics has been critiqued by disability studies for rendering care receivers passive recipients of care (Williams 2001, pp. 478–479).Footnote 15 While existing power differences in the care encounter should not be disregarded, the concept of will-work is explicitly not applicable to the work of care workers only: care receiver’s wanting may be aligned to having a shower, but the caregivers’ wanting may also be aligned to flexibly adjust to what the care receiver wants. This could take the form of providing assistance with a shower later, asking another caregiver to step in or perhaps reconsidering whether the task at hand is necessary at all.

I contend that doing will-work (rather than neglecting or overruling residents’ wanting) makes the caregivers’ work good care. Good care includes being attentive to people’s desires and striving ‘to lighten what is heavy, and even if it fails it keeps on trying’ (Mol et al. 2010, p. 14) . Good dementia care, then, ‘persistently strives to create conditions for and enable better interaction, and also to afford people living with dementia positions in which they can act and exert valued forms of subjectivity’ (Moser 2010a, p. 295). Coercion or neglect forecloses opportunities for ‘better interaction’. Through coercion , positions in which subjectivity can be exerted are not afforded, and wanting can, by definition, not be shared. If wanting cannot be done together, and cannot be aligned, it remains unilateral—which can be harmful in situation where one must agree and where there are power differences. In these situations, will-work aims to achieve what is good for those living with dementia (an assertion that often relies on professional knowledge) in a way that is pleasant for the resident as well as for the caregiver. At the same time, it must includes a reflecting upon whether the task at hand must be completed now, and in this particular way.

In the remaining pages, I describe the work care workers do on residents’ wanting as (1) sculpting moods and emotions, (2) managing attention and (3) creative negotiation involving time and materialities.

Sculpting Moods and Emotions

The first way in which will-work is done, begins before something is wanted. Consider the following interview excerpt:

- Annelieke::

-

Can you tell me something about ADL-care and dementia, and what is specific for people with dementia, particularly when compared to people with somatic complaints?

- Leandra::

-

Specific? I think it differs, and depends on the person [you are dealing with] and how you deal with it. […] I always adjust to how advanced someone is [in his/her dementia].

- Annelieke::

-

Hmm. What do you mean? Or—what do you do?

- Leandra::

-

You walk in [to the resident’s room] and then you try to come in as ‘cheerfully’ [luchtig] as possible.

- Annelieke::

-

Do you mean like [happy tone of voice] ‘Hallo’?

- Leandra:

-

Yes, you try to brighten up the room when you walk in [het zonnetje in huiszijn]. I notice that Ms Koch, […] when I go there and I am cheerful, then she also becomes cheerful. [I]magine you come in looking all serious, not even sad, but just neutral, […] then she is already more sad. So, the emotion that you radiate, she magnifies that. [Sometimes] you notice that nothing works and that [the fact that she does not want to be washed] is due to her mood at that moment. […] But I see that it works when I enter happily, because it relaxes her and she will allow me to do more.

This example shows Leandra doing will-work. She wants to shower Ms Koch.Footnote 16 In order to do this, she needs Ms Koch to want to shower, or at least to not refuse it. Leandra’s initial use of the generic ‘you’ indicates that entering the room cheerfully is a more general way of approaching residents. But she then adjusts to the person herself and to the severity of the resident’s condition, as is evidenced in Ms Koch’s example. In other words, generalisations are not useful here. To get Ms Koch to want to shower, Leandra attempts to sculpt her mood. Although sometimes ‘nothing works’ and wanting remains not amenable to Leandra to work upon it, sometimes it does work: in those situations, Leandra’s smile causes Ms Koch to ‘also become cheerful’, to ‘magnify the emotion’ and to relax. This, in turn, results in her allowing Leandra ‘to do more’, including giving her a shower.

In another example of this way of doing will-work, Joani often brought three cups of hot chocolate to Ms Veenstra along with her medicine. We drank the chocolate by her bedside together. Meanwhile, we talked about the weather or what we had done yesterday, or about the joint breakfast awaiting her downstairs. By doing this, Joani hoped to get Ms Veenstra into the mood for getting out of bed, and it often worked. In those cases, what Ms Veenstra wanted was aligned with Joani’s desire for her to have breakfast, and for her to be with others.

Sculpting moods and emotions is one way to align wanting. Two important conclusions can be drawn from this. Firstly, the story affirms that moods and emotions cannot be separated from wanting.Footnote 17 Secondly, it shows will-work as a relational practice: Ms Koch and Leandra are responsive to one another’s moods, smiles and tone of voice. Joani and Ms Veenstra first had a chat, after which wanting to get up could become a shared desire. Thirdly, materialities, such as cups of hot chocolate or breakfast, may be part of the attempt to align wanting.

Managing Attention

So far, I have described how care workers sculpt moods and emotions that then allow residents to want what care workers want for them. Sometimes, when Leandra enters the room cheerfully, Ms Koch ‘magnifies the emotion’. Leandra’s cheerfulness changes Ms Koch’s mood and thus her willingness to take a shower. But ‘coming in cheerfully’ is not enough. What do care workers do to keep the wanting aligned once they walk through the door? Leandra engages in a second way of will-work after she has entered the room cheerfully:

- Annelieke::

-

Okay, […] you try to brighten up the room when you walk in. […] And then?

- Leandra::

-

And then you start instructing [the resident]: ‘what are we going to do today’ […] and instead of pausing for a long time afterwards [you] talk about other things and […] you keep control over the topic of conversation. You have the lead in what happens. […] Take Ms Stein, if you tell her ‘Good morning, I will give you a nice wash’, she will say ‘yes, but but but […]’. But if you right away talk about something else, then the ‘but but’ that you could expect is over. Then she is already somewhere else. […] I say: ‘How did you sleep?’, ‘Not so well’. Then I say ‘How is that possible? Was it too warm? Was it too cold?’ ‘Well no, no, I don’t know. I don’t know’. ‘Are you hungry?’ ‘Yes, I am quite hungry’ ‘Well, then I will [say] ‘look, a wash cloth’ or something, you know, ‘Then you can have a nice breakfast. What would you like? White bread, brown bread? A whole conversation about what is about to happen. […] Well, then you are nicely engaged. I am too; I don’t like saying nothing. So it is also nicer for […] me.

Leandra seems to imply that Ms Stein’s cannot want something other than the tasks at hand—being washed while having a conversation. In other words, doing wanting (here, not wanting to shower) requires Ms Stein’s attention . Doing will-work in this situation entails managing that attention: Leandra orients Ms Stein towards what they are going to do, away from not wanting to shower, and times her questions to ‘keep control over the topic of conversation’. In doing so, Leandra keeps Ms Stein’s ‘yes but’ at bay. By ‘talking about something else’, Leandra can distract Ms Stein from the task at hand and let it go almost unnoticed. Leandra thus prevents that Ms Stein comes to want something other than a shower. When Leandra ‘has the lead in what happens’, Ms Stein is ‘already somewhere else’ instead of in her rejection of the washing. Both are ‘nicely engaged’. This affects Ms Stein positively: if she is off to a good start, she is more likely to enjoy the rest of her day as well.

In a similar vein, Anja manages the residents’ attention by offering a choice about the timing of showering, rather than about showering itself:

- Anja::

-

My biggest trick is to give people one choice, no discussion. I ask […]: ‘would you like to shower now or in half an hour?’ Then they feel like they have a say in it, although they do not [have a say about whether to actually have a shower or not] … ‘It would be nice if you would wear a clean shirt today. Do you want this one or that one?’ (She holds up her hands as if she is holding two shirts next to each other.) Idem ditto with ‘do you want to have a shower now or in thirty minutes?’ In fact, they do not get a say. … ‘Yes…’; ‘That one’ (and she points to one of her hands with the imaginary shirt). It simply is a bath-day! Then [when I pose this question], they are often so overwhelmed, that they just come along. (Emphasis original)

Anja emphasises that, if she does not provide ADL-care, she says that she knows she is ‘not providing good care’. Good care, as described by Anja here, means to make the resident want what Anja thinks is good for her. In providing a binary choice about timing, she offers the resident a sense of choice, yet makes sure that she chooses the shower, which Anja says is good for her.

Leandra and Anja manage the resident’s attention to prevent that she may come to want something other than what they, as her care workers , contend is good for her. One could argue that these ways of doing will-work are manipulative.Footnote 18 If we consider the will to be a fixed entity, it may well be. But if, as I suggested, we see wanting as done in unfolding sociomaterial interaction (which may include cups of hot chocolate, smiles and a cheerful tone of voice, as well as attempts to keep control over the conversation), we can understand the attempts to manage attention as attempts to turn wanting into a relational activity, rather than an individual one: Care workers take what residents want as something that can be worked upon and made relational in the care encounter. In doing so, care workers take residents’ wanting seriously in that it cannot simply be overruled, but neither can it be taken to be a fixed entity which cannot be changed. Rather than forcing their will upon residents, care workers remain in conversation. They offer a sense of choice where perhaps there is none (as Anja put it, it may be ‘simply a bath-day’!Footnote 19), but do not merely impose something on the resident . Managing attention is thus part of the larger attempt to align wanting in a way that ensures that care tasks that care workers deem necessary get done, in a way that is as pleasant as possible for both people involved. At best, both are ‘nicely engaged’.

Creative Negotiation Involving Time and Materialities

Leandra enters the room in a friendly mood. She controls the conversation and diverts the residents’ attention away from coming to want something other than the care task at hand. Anja offers a choice on time, rather than on the task itself. These are ways to work on residents’ wanting before they fixate on wanting something. In this section I describe how care workers attempt to modify what a resident wants when a resident already expressed a wanting before it could be sculpted. I call this work ‘creative negotiation’.Footnote 20

First and foremost, care workers ask residents for their ‘cooperation’ in the care activity. If this does not work, care workers also reason with residents, either jokingly or seriously. Herein they often argue based on visible materialities in the present (‘Look, your shirt is dirty’), relating them to what is to be done now (‘Let’s put on a clean shirt’) or in the near future (‘Don’t you want to look clean when your family visits this afternoon?’). These strategies seem to appeal to a cognitive willing (resonating the philosophical understanding of the will)—which is precisely what residents in the early stages of dementia seem to be losing grip on—but not to an emotional wanting. Indeed, these strategies do not work with all residents, and certainly not every time.

If reasoning does not work, there are other strategies. Care workers , for instance, play with the timing of caregiving. When Mr Bakker does not want to get up, Joani often asks: ‘Would you like me to come back in half an hour?’ If he agrees, she simply helps the residents in a different order, creating a temporary alignment between what she and Mr Bakker want: to not shower (just yet). Mr Bakker is often willing to get up after half an hour or so, perhaps having fulfilled his desire to stay in bed longer, or perhaps having forgotten his reluctance to get up in the first place. As such, time helps in aligning wanting.Footnote 21

When continuing attempts to align the residents’ wanting with their own become too challenging, care workers sometimes call upon a colleague to take over. Care workers remain patient with the resident by putting space between themselves and a resident whose wanting remained not amenable to negotiation. Sometimes a specific colleague is asked. This once again highlights the relational nature of will-work: if a care worker gets along well with a resident, aligning wanting becomes easier to do. For instance, when nobody can get Ms Veenstra out of bed and Lucia is working that day, her colleagues ask her to come and help. Lucia can ‘pull off’ a stricter approach and ‘get away with it’. She can tell Ms Veenstra: ‘My dear, you stink, you must get up’. Anja said: ‘Ms Veenstra would get angry at any other care worker for saying anything of the sort, but she loves Lucia’.

Like the cups of hot chocolate worked for sculpting wanting, materialities can also play a role in creative negotiation. Take the case of Mr Bakker. Convincing Mr Bakker to wear clean clothes and to take a shower poses a challenge every day. He is known to feel cold and claustrophobic, so that the bathroom door cannot be closed to make him feel warmer. Mr Bakker has vascular dementia and is aphasic: he can utter short sentences, with the occasional loss of a word. Not being able to find and understand words frustrates Mr Bakker and reasoning is likely to upset him. Joani is particularly skilledFootnote 22 in finding alternatives to reasoning by ‘creatively negotiating’ with him, not only verbally, but also non-verbally: one day, when faced with his refusal to take a shower, she gave him a foot bath. Then he wanted the shower.

In talking about this situation, Joani and I offered differing explanations for why the foot bath had worked. I suspected that giving Mr Bakker the foot bath made him feel less cold, undoing his reason to refuse the shower. Joani said: ‘The foot bath gets him out of his head. If he puts his feet in warm water—maybe he remembers something, that he walks down the beach for instance—but once his feet feel the warm water, he would have to hold onto his thoughts of “not wanting to shower” very rigidly’. Joani imagines that the sensation of warm water on his feet reminds Mr Bakker of the ocean. This goes further than to think about the ocean: the water makes him feel something he has felt before and thus conjures up (hopefully happy) memories. This pleasant feeling, then, in her understanding, made him let go of his opposition to showering.

How the foot bath ‘really’ changed Mr Bakker’s wanting is up for speculation. But two other points illustrate my argument about daily wanting and will-work here. Firstly, wanting something seems highly entangled with the feeling body , which may then be ‘tinkered with’ (cf. Mol et al. 2010) in the context of the care relationship . In doing will-work, the feeling body may be skilfully appealed to. Secondly, not only interactions between people sculpt or prevent a specific wanting, but so do non-human actors: here, work on Mr Bakker’s wanting required a foot bath. If the foot bath had not been part of the encounter, Joani could have tried cheering up Mr Bakker, arranging another time slot for his care or asking one of her colleagues to take over. But instead, the will-work was ‘delegated’ (Latour 1988, p. 299) to the foot bath. Herewith, it becomes clear that will-work can be done involving objects: the foot bath creates the material conditions that work upon what Mr Bakker enjoys, and in doing so, change what Mr Bakker wanted. The foot bath opened up an avenue for Mr Bakker to want a shower.

Conclusion

In this chapter, I set out to explore in more detail the way in which daily wanting is worked upon in the context of unfolding sociomaterial interaction in residential dementia care, and I asked what we may learn about good care from taking a closer look at these practices. I stated that wanting is an expression of subjectivity, and being respected in this is a prerequisite for living a good life with dementia. At the same time, wanting something is a relational process. How it is acted upon thus is an ethical and political question. Nobody wants to constantly be overruled by another person, and indeed much work goes into avoiding coercing somebody. To describe what is done instead, I coined the term ‘sociomaterial will-work’. The concept highlights care workers’ and residents’ attempts to align the other’s wanting with their own as a form of labour and as dependent on sociomaterial relations. I described care workers doing will-work by (1) sculpting moods and emotions, (2) managing attention and (3) creative negotiation involving time and materialities. With smiles, cups of hot chocolate and foot baths, changes to the order in which care is provided and to who shows up at a resident’s bed, care workers strive for a positive way of relating—of being ‘nicely engaged’ in conversation and activity. Will-work ventures into the space between doing nothing and exerting force. It is the ‘urging’ that care workers name when seeking alternatives for coercion and neglect. I have argued that this aligning residents’ wanting makes the caregivers’ work good care.

I have offered an alternative understanding of the will—namely as something that is ‘done’ in sociomaterial interaction, in which it can be aligned by making it relational. Indeed, instead of dismissing ‘daily wanting’ of those living with dementia, my analysis enables thinking about it. At the same time, the finding that moods and the feeling body can be appealed to in care encounters and that materialities can be used in creative negotiation with residents, offers new ways of thinking about what good care may entail in situations in which residents want something that their care workers understand as ‘not good’ for them. As such, my contribution is one that can inform care practice.

Some may say I have painted a rather ideal picture. What can be done when ‘nothing works’, which, as Leandra noted, sometimes happens? In these cases, will-work seems to hit its limit and coercion may seem the only way to get a task done (we may think again of Ms Lichthart, who, covered in faeces, resisted a shower). It is important not to forget that people living with dementia, who are often aphasic and have a fragmented memory, are particularly vulnerable to maltreatment and situations in which what they want (or resist) is overruled. Doing will-work requires the continuous reflection upon the fine line between ‘urging’ and ‘coercing’. Once, when Ms Veenstra did not want to get out of bed, her care worker Linda turned on the TV, radio and shower, and pulled away her blankets. These were trying moments of participant observation, as being there without doing anything about it made me complicit. Upon my inquiry why Linda did this, she explained: ‘This will annoy her so much that she will get up. She is better off if she gets up and eats something’. Paradoxically, Linda was convinced that what she was doing was caring. The example shows that a care worker can easily abuse his or her power , even if the actions are based on the idea that the resident in question is ‘better off’ like this. But the way in which care tasks are achieved matters. Coercion , neglect and incisive refusal leave no room for alignment in wanting. Wanting, in those situations, remains unilateral and cannot be shared. Although coercion does indeed result in Ms Veenstra getting up, how this is achieved imposes what Linda wants on her; wanting, instead of being done together, remains unilateral. Indeed, it is dubious whether this can still be called good care.

I contend that will-work has failed when a resident is coerced into doing something. Sociomaterial will-work makes good care only if care workers continue to attempt to align residents’ wanting with what they think is good for them, after critically reflecting on the question whether this is indeed so. If will-work fails, coercion and neglect remain tragic occurrences. But if given enough time, trust and support, care workers doing will-work may indeed realise the proverbial ‘otherwise’ (Star 1990, pp. 89–90), enabling residents like Ms Lichthart to want the shower that they need.

I do not want to make it seem that care work is easy. On the contrary, I explicitly want to acknowledge that persistent tinkering without ‘successes’ requires a lot of patience, which under trying circumstances is sometimes sheer impossible. This is why time, energy and motivation are indeed essential for retaining the flexibility that is needed to do will-work in delicate care situations with frail and fragile residents. Cuts to staff, the subsequent increase in work load and a lack of trust within care teams are detrimental to the care staff’s ability to do good care. Under such circumstances, residents such as Ms Lichthart covered in faeces are sometimes forced to shower. At the same time, however, good care is already being done. I have taken all examples presented in this chapter from what I have seen in the care homes where I conducted my research. In writing about these, rather than about the situations in which care falls short, I hope to give this work the attention it deserves. I use these examples to hold up to others: that way, what already works well, can be done more often.

Notes

- 1.

Like any text, this text is the result of a collaborative effort. I would like to extend my gratitude to the Gieskes-Strijbis Fonds for funding this research. I owe my deepest thanks to the care institutions which granted me access for my fieldwork, and the care professionals and residents who gave so much of their time to me, and patiently took me along in their daily life and work. In particular, I would like to thank the organisers of the summer school that led to this book, Joachim Boldt and Franziska Krause, and to the summer school’s participants, whom I can now proudly call my esteemed co-authors and friends. Special thanks go to Patrick McKearney and my dear colleagues at the University of Amsterdam, of whom I want to mention in particular Willemijn Krebbekx, Else Vogel, Lex Kuiper, Annekatrin Skeide, my in the Anthropology of Care research group Silke Hoppe, Laura Vermeulen, Natashe Lemos Dekker and Susanne van den Buusethe members of the Writing Care Seminar and the Walking Seminar Amsterdam. Daniel Guinness, thank you for editing my English! Lastly, but with emphasis, I want to thank my supervisors at the University of Amsterdam: Anne-Mei The for giving me the opportunity to do this research, and Jeannette Pols and Kristine Krause for being such a big source of inspiration and support throughout the research and writing process.

- 2.

All names used in this chapter, for sites as well as interlocutors, are pseudonyms.

- 3.

‘Zonneweide’ (a fictitious name) is one of three care homes in which I conducted ethnographic fieldwork. It is a care home in a sub-urban area in the Netherlands and home to 50 people with a wide variety of diagnoses. Fifteen of them live on the floor reserved for people with early stage dementia, although, if possible, residents live here until they pass away. Recent changes in Dutch health care policy resulted in the closing of many of the care homes that are providing care to people with ‘lower’ care needs. Those that remain open, like Zonneweide, are increasingly providing care to people with ‘higher’ care needs, including those in the later stages of dementia.

- 4.

For purposes of legibility, I use the female pronoun to refer to residents and care workers in general.

- 5.

The caregivers’ reasons to want something pertain to achieving a high level of well-being for the resident in question, and thus doing their job well. In a way, it is thus what professional caregivers want for residents and for themselves. If wanting can be aligned, the situation is significantly more pleasant for both parties involved.

- 6.

In this chapter, I focused on those situations in which residents want something else than the care worker (s) in care encounters that centre around activities of daily living (ADL). These particular situations are characterised mostly by a resident not wanting to do what the care worker has to ‘get done’: getting residents up, bathing and dressing them. I have chosen these situations because they most clearly bring out how wanting is negotiated in care encounters . However, in focusing on ADL care, my writing seems to suggest that residents merely refuse and hardly actively want anything. This is not the case in practice: residents want many things, some of which are equally ‘problematic’ for care workers (such as wanting to go home, contiuously wanting to go to the toilet or desiring intimacy with other residents. In those situations the family’s wishes may also play an important role, a party that I have not been able to include in this chapter). By the same token, the situations in which residents do not necessarily want anything, but care workers stimulate them to do so, are left out. Both this ‘wanting something’ and the ‘activation to want something’ warrant further exploration.

- 7.

In English, a person is said to no longer have legal capacity or to be (legally) incapacitated.

- 8.

The issue of admitting somebody to a nursing home against her will is more complex than can be accounted for within the scope of this chapter. It must be noted here, however, that admission against somebody’s will is only possible if (a) somebody is endangering her own or other peoples’ safety, (b) this situation cannot be resolved without admission to a nursing home and (c) a BOPZ-indication is assigned [a designation assigned to the person by a medical professional under the law of ‘Bijzondere Opnemingen in Psychiatrische Ziekenhuizen’ (Special admissions in psychiatric hospitals)] (cf. Rijksoverheid n.d.).

- 9.

I build my argument with ethnographic material that I gathered during 14 months of fieldwork in three Dutch care institutions between summer 2013 and fall 2015. In all three care institutions I met the residents , and observed and participated in their daily activities. Additionally, I observed and participated in care practices , helping care workers with their ADL-tasks on the wards during day, evening and night shifts. I conducted interviews with carers and family members. The analysis consisted of a careful readings and re-readings of all interview transcripts and field notes. I coded the data for recurring themes, using NVivo qualitative data analysis software. One of these themes is ‘daily wanting’ on the ward and how it was negotiated in care encounters, the analysis of which I present in this chapter. Ethical consent for the research was obtained from the Anthropology Ethics Board of the University of Amsterdam.

- 10.

I deliberately choose the term ‘wanting’ over ‘agency’. While agency, most generally, refers to the ‘socioculturally mediated capacity to act’ (Ahearn 2001, p. 112), hence potentialities of action, I here discuss actual practices in which wanting is done, and thus actually takes place.

- 11.

This approach is useful to make visible how people with dementia who can no longer express themselves in verbally coherent ways, are nevertheless actors in the world. However, it simultaneously makes invisible mixed motives and intentions. If, for example, a resident steps into the shower upon the urging of her care worker , this action could, instead of an enactment of the will, also be a way to please her, or to put an end to the conversation. These considerations cannot be grasped through the approach chosen.

- 12.

The statement can be said to reflect a wider shift away from coercive measures in Dutch health care, and may thus have been related to the language used in culture change programmes aiming to change care workers’ attitude towards the use of coercion . At the same time, neglect, or the milder form of ignoring somebody, was less discussed. These situations (for instance, when a resident indicates that she wants to use the toilet, but care workers assert that ‘she does not really need to go, she just thinks she does’) merit more analysis.

- 13.

For purposes of brevity, I hereafter use ‘will-work’.

- 14.

I chose to call the practice ‘will-work’ rather than ‘wanting-work’ because it allows me to put my writings in conversation with philosophical work on the will.

- 15.

Interestingly, disability studies itself has been critiqued for putting care recipients into the same position (Winance 2010, p. 95).

- 16.

For a wonderful analysis of repertoires in washing practices, see Jeannette Pols’s ‘Washing the citizen’ (Pols 2006).

- 17.

This illustrates the entanglement of will-work and emotional labour, defined by Arlie Hochschild as the ‘management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial and bodily display’ (Hochschild 1983, footnote p. 7) which ‘requires one to induce or suppress feeling in order to sustain the outward countenance that produces the proper state of mind in others’ (ibid., p. 7). Here, Leandra manages her own facial display to produce a happy state of mind in Ms Koch, who is then more likely to want a shower.

- 18.

For an interesting reflection on deception and dementia, see ‘Nothing but the truth? On truth and deception in dementia care’ (Schermer 2007).

- 19.

On a critical note: it is important that care workers keep asking themselves whether the resident really cannot skip the shower, or really does not want to shower—if the answer is no to both, then the shower may just be postponed, therein aligning the care worker’s wanting with what the resident wants.

- 20.

It goes without saying that the examples of creative negotiation provided here are not an exhaustive list. Whenever one ‘way of doing things’ did not work, care workers mostly tried another one, or combined them creatively. Therefore the list should not be seen as a scheme of possible actions, but rather to give an idea of how care workers improvise in situations in which residents’ wanting does not align with what caregivers believes to be good for the resident (and thus with what the care worker would want the residents to want as well).

- 21.

Interestingly, asking and rearranging the order in which residents are helped during the morning shift can become part of the daily routine too, without clashing with the efficiency-based logic of work in today’s Dutch care homes. Indeed, investing time in doing will-work may thus even contribute to efficiency in some instances. As a care worker told me in response to a presentation of this chapter during a ‘Dialogue meeting’ [Dialoogbijeenkomst] organised by the Long Term Care and Dementia research team I am part of, if a resident does not want to get dressed, time may be best spent ‘seducing’ that person into wanting to get dressed, rather than spending time in forcing the person into her clothes, as the latter action may be less pleasant for caregiver and care receiver, as well as more time consuming.

- 22.

Clearly, it is necessary to take into account that these are largely personal and cannot be transferred from one care worker to another in every case. Indeed, not all care workers put as much creativity into the negotiation with residents . For instance, when Joani told Lucia about the foot bath she had given to Mr Bakker, Lucia replied ‘I am not going to do that!’.

References

Ahearn, L. M. (2001). Language and Agency. Annual Review of Anthropology, 30, 109–137.

Brand, M. (1995). Volition. The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Gimlin, D. (2007). What Is “Body Work”? A Review of the Literature. Sociology Compass, 1(1), 353–370.

Harbers, H., Mol, A., & Stollmeyer, A. (2002). Food Matters. Theory, Culture & Society, 19(5/6), 207–226.

Higgs, P., & Gilleard, C. (2015). Rethinking Old Age: Theorising the Fourth Age. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hochschild, A. R. (1979). Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure. American Journal of Sociology, 85(3), 551–575.

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jerak-Zuiderent, S. (2015). Accountability from Somewhere and for Someone: Relating with Care. Science as Culture, 24(4), 412–435.

Latour, B. (1988). Mixing Humans and Nonhumans Together: The Sociology of a Door-Closer. Social Problems, 35(3), 298–310.

Law, J. (2009). Actor Network Theory and Material Semiotics. In B. S. Turner (Ed.), The New Blackwell Companion to Social Theory (pp. 141–158). Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Mol, A. (2002). The Body Multiple. Ontology in Medical Practice. Durham: Duke University Press.

Mol, A. (2008). The Logic of Care: Health and the Problem of Patient Choice. New York: Routledge.

Mol, A., Moser, I., & Pols, J. (Eds.). (2010). Care in Practice: On Tinkering in Clinics, Homes and Farms. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Moser, I. (2010a). Perhaps Tears Should Not Be Counted but Wiped Away: On Quality and Improvement in Dementia Care. In A. Mol, I. Moser, & J. Pols (Eds.), Care in Practice: On Tinkering in Clinics, Homes and Farms (pp. 277–322). Bielefeld: Transcript.

Moser, I. (2010b). Dementia and the Limits to Life: Anthropological Sensibilities, STS Interferences, and Possibilities for Action in Care. Science, Technology, & Human Values, 36(5), 704–722.

Murphy, K. M., & Throop, C. J. (Eds.). (2010). Toward an Anthropology of the Will. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Pols, J. (2005). Enacting Appreciations: Beyond the Patient Perspective. Health Care Analysis, 13(3), 203–221.

Pols, J. (2006). Washing the Citizen: Washing, Cleanliness and Citizenship in Mental Health Care. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 30(1), 77–104.

Rijksoverheid. (2014). Dwang in de zorg bij geheugenproblemen (dementie): wilsonbekwaam. Dwangindezorg.nl. Retrieved from https://www.dwangindezorg.nl/begrippenlijst/wilsonbekwaam

Rijksoverheid. (n.d.). Gedwongen opname in de zorg. Rijksoverheid.nl. Retrieved March 31, 2016, from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/geestelijke-gezondheidszorg/inhoud/gedwongen-opname-en-dwang-in-de-zorg

Schermer, M. (2007). Nothing but the Truth? On Truth and Deception in Dementia Care. Bioethics, 21(1), 13–22.

Star, S. L. (1990). Power, Technology and the Phenomenology of Conventions: On Being Allergic to Onions. Sociological Review, 38(S1), 26–56.

Strauss, A., Fagerhaugh, S., Suczek, B., & Wiener, C. (1982). Sentimental Work in the Technologized Hospital. Sociology of Health and Illness, 4(3), 254–278.

Throop, C. J. (2010). In the Midst of Action. In K. M. Murphy & C. J. Throop (Eds.), Toward an Anthropology of the Will (pp. 24–49). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Tronto, J. (1993). Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. London: Routledge.

Twigg, J. (2000). Carework as a Form of Bodywork. Ageing and Society, 20(4), 389–411.

Twigg, J., Wolkowitz, C., Cohen, R. L., & Nettleton, S. (2011). Conceptualising Body Work in Health and Social Care. Sociology of Health & Illness, 33(2), 171–188.

Van Hout, A., Pols, J., & Willems, D. (2015). Shining Trinkets and Unkempt Gardens: On the Materiality of Care. Sociology of Health & Illness, 37(8), 1206–1217.

Vogel, E. (2017). Hungers that Need Feeding: On the Normativity of Mindful Nourishment. Anthropology & Medicine, 1–15. doi:10.1080/13648470.2016.1276322.

Williams, F. (2001). In and Beyond New Labour: Towards a New Political Ethics of Care. Critical Social Policy, 21(4), 467–493.

Winance, M. (2010). Care and Disability: Practices of Experimenting, Tinkering with, and Arranging People and Technical Aids. In A. Mol, I. Moser, & J. Pols (Eds.), Care in Practice: On Tinkering in Clinics, Homes and Farms (pp. 93–117). Bielefeld: Transcript.

Wolkowitz, C. (2002). The Social Relations of Body Work. Work, Employment and Society, 16(3), 497–510.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

This chapter is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Driessen, A. (2018). Sociomaterial Will-Work: Aligning Daily Wanting in Dutch Dementia Care. In: Krause, F., Boldt, J. (eds) Care in Healthcare. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61291-1_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61291-1_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-61290-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-61291-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)