Abstract

My text offers an attempt to justify theoretically the existence of an important pillar of contemporary constitutional democracy: judicial review. Why do Supreme and Constitutional Courts that are not electorally accountable organs have the power to modify and occasionally cancel from the books statutory legislation passed by elected and accountable representatives? The argument presented discusses and questions the standard doctrine of the separation of powers and is based on the foundations of modern political authority as the agency the function of which is to protect and guarantee citizens’ rights.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

I agree with Sharon Lloyd’s interpretation when she writes, “ Hobbes sought to discover rational principles for the construction of a civil polity that would not be subject to destruction from within […] Hobbes further assumes as a principle of practical rationality, that people should adopt what they see to be the necessary means to their most important ends [notably the natural right of self preservation]” (Lloyd 2014).

- 2.

On the meaning of this expression, see Pasquino (2012).

- 3.

- 4.

I’m now old enough to know the very limited possibility of modifying entrenched constitutional conventions, and more important, I have no pretensions at all to suggest anything to my American colleagues being a sort of institutional pluralist and not an expert on the American political and constitutional system. By “institutional pluralist” I mean, in the tradition of Machiavelli’s Discorsi, that what is good and possible for Florence may not be possible for Naples. Or, to use a more contemporary example, that good institutions for Sweden (uni-cameralism and parliamentary system with an incipient and timid constitutional adjudication) are not exactly the same as those that are good for the USA or for Afghanistan.

- 5.

I define this form of government by the presence of three elements: (1) a representative government based on universal suffrage, where there are regular, repeated, and competitive elections; (2) a rigid constitution, encompassing fundamental rights and some form of separation in the exercise of political authority; (3) an independent judicial organ in charge of the guardianship of the constitution, which is called in Europe a constitutional court, council, or tribunal.

By accountability I mean the need of an agent or organ elected pro tempore to return to the electoral body to be renewed in her/his mandate. There are many other possible definitions, but in my text the term means only and exclusively what I stipulate.

A definition of constitutionalism as a key aspect of constitutional democracies is the one offered by J. Weiler (2011: 9) that I share: in a constitutional legal order “the constitution meant a higher law with the apparatus of judicial review and constitutional enforcement.”

- 6.

Sub voce democracy we read: “(3) a form of government, usually a representative democracy, in which the powers of the majority are exercised within a framework of constitutional restraints designed to guarantee all citizens the enjoyment of certain individual or collective rights, such as freedom of speech and religion, known as liberal, or constitutional, democracy” The New Encyclopedia Britannica (1993); p. 5 sub voce Democracy, that the guarantee of rights is for good reasons the task of a court of justice (rather than other possible alternatives) is the object of this text.

- 7.

On this question, see now the important book by Gardbaum (2013).

- 8.

This seems to be the opinion of Adam Przeworski (2011) where p. 160 the author shows, moreover, strong skepticism vis-à-vis constitutional adjudication and a clear preference for majoritarian democracy (on this book see my review in La vie des idées: http://www.laviedesidees.fr/Le-peuple-en-democratie.html?lang=fr)

- 9.

Concerning the German Constitutional Court, see: Simon (1994).

- 10.

See a partial English translation of this book in: http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=kt209nc4v2&chunk.id=ch01&toc.depth=1&toc.id=ch01&brand=ucpress Now there is a complete translation of this fundamental text: (Kelsen 2013).

In the Chapter on Administration, there is the only reference to constitutional adjudication (p. 83): “…not only individual administrative acts but also general regulative norms and especially laws can and must be submitted to judicial control – the former with respect to their legality and the latter with respect to their constitutionality. This control falls under the jurisdiction of a constitutional court, whose function is all the more important for democracy, the more the enforcement of the constitution in the legislative process is in the eminent interest of the minority and the more the rules regarding quorum, a qualified majority, etc., serve – as we have already seen [in the chapter I] – to protect that minority. […] The fate of modern democracy depends to large extent on a systematic development of all types of institutional controls. Democracy without such controls is impossible in the long run.”

- 11.

In the crucial section of his book devoted to the conditions for the success of the democratic method, the Austrian economist wrote nonetheless this important remark—on which I have to come back in another section of my research:

“The second condition for the success of democracy is that the effective range of political decision should not be extended too far. How far it can be extended depends not only on the general limitations of the democratic method which follow from the analysis presented in the preceding section but also on the particular circumstances of each individual case.” p. 291.

- 12.

An important exception is the American political theorist Robert Dahl (1989).

- 13.

See some of the most relevant texts of this debate in Vinx (2015).

- 14.

See now the partial English translation of this text in the book quoted at the FN 32.

- 15.

See FN 48 hereafter.

- 16.

Schmitt distinguishes not only statutory legislation from the constitutional provisions (Verfassungsgesetzte) but also the latter from the positive Verfassung, the constitutional core, which can be modified only by the citizens, the holders of the pouvoir constituant. This point has been repeated by the German Constitutional Court that claimed that only the German people and not even the elected representatives can abandon the German national sovereignty in favor of an European federal state (what is the real core of the German national sovereignty or identity (?) is not clear either in Schmitt or in the famous Lissabon Urteil of the German Bundesverfassungsgericht).

- 17.

Elsewhere (Pasquino 1994a), I argued that Schmitt and Kelsen were not really speaking of the same question. Here I’m simply trying to show that the objections that Schmitt presented against the constitutional adjudication are a sort of Ur-criticism later on systematically repeated.

- 18.

I discuss the sense of word “political” in this context in QUADERNI COSTITUZIONALI 2015.

- 19.

See my text on the neutrality of Constitutional Courts (unpublished).

- 20.

Schmitt’s position on this question is presented accurately by Le Divellec (2007).

- 21.

Emmanuel Sieyes used the word électionisme in his manuscripts to characterize his doctrine of the representative government. Electoralism is used here to qualify the theories of contemporary democracy that reduce this form of government to electoral accountability and majority rule.

- 22.

See also Kelsen (1928); this text is the French translation (probably by Charles Eisenmann) of the text presented by Kelsen in 1927 at the meeting of the German-speaking professors of public law in Vienna.

- 23.

One can think that the authoritarian regime established by Fidesz in Hungary through a constitutional revision deprived the Hungarian Constitutional Court of almost any power of controlling the government.

- 24.

- 25.

This distinction is already in John Locke’s Second Treatise; see Pasquino (1998b).

- 26.

Nugent translation

[http://ia700305.us.archive.org/31/items/spiritoflaws01montuoft/spiritoflaws01montuoft.pdf], p. 151; the original text reads: « Il y a dans chaque État trois sortes de pouvoirs: la puissance législative, la puissance exécutrice des choses qui dépendent du droit des gens, et la puissance exécutrice de celles qui dépendent du droit civil. »

- 27.

On the federative power and its modern developments, see Kaufmann (1909).

- 28.

« Par la première, le prince ou le magistrat fait des lois pour un temps ou pour toujours, et corrige ou abroge celles qui sont faites. Par la seconde, il fait la paix ou la guerre, envoie ou reçoit des ambassades, établit la sûreté, prévient les invasions. Par la troisième, il punit les crimes, ou juge les différends des particuliers. On appellera cette dernière la puissance de juger, et l’autre simplement la puissance exécutrice de l’État. », ibidem.

- 29.

On this fundamental: Landi (1981).

- 30.

This expression means, in the best interpretation I know, not that the judicial function is without any power, but that it is not attributed to a permanent body of magistrates, since exercised by jurors: “The judiciary power ought not to be given to a standing senate” (Engl. Transl., p. 153).

- 31.

- 32.

P. 155; “Il y a toujours dans un État des gens distingués par la naissance les richesses ou les honneurs; mais s’ils étaient confondus parmi le peuple, et s’ils n’y avaient qu’une voix comme les autres, la liberté commune serait leur esclavage, et ils n’auraient aucun intérêt à la défendre, parce que la plupart des résolutions seraient contre eux. La part qu’ils ont à la législation doit donc être proportionnée aux autres avantages qu’ils ont dans l’État: ce qui arrivera s’ils forment un corps qui ait droit d’arrêter les entreprises du peuple, comme le peuple a droit d’arrêter les leurs.

Ainsi, la puissance législative sera confiée, et au corps des nobles, et au corps qui sera choisi pour représenter le peuple, qui auront chacun leurs assemblées et leurs délibérations à part, et des vues et des intérêts séparés.”

- 33.

- 34.

On the rationale of the independent exercise of the judicial function, see Pasquino (2001a). The bottom line of the argument seems to be the following: Montesquieu speaking of the separation of powers in England was defending the idea that the agencies that have to exercise the function of applying the laws need to be independent from the agency which exercises the function of making law. Why? To avoid judicial decisions ad personam. A loi for Montesquieu, likewise for Locke, is/has to be a general abstract commandment—cannot be a bill of attainder meaning a norm targeting a specific subject. So the judge cannot make special decisions, since he has to enforce the law that is general and equal for everyone (how is that compatible with a society of ranks cannot be discussed here). In this sense the citizen is protected vis-à-vis the extemporary decrees of a biased judge (and moreover he can appeal, at least in the contemporary judicial systems) against a judge’s decision which seems arbitrary). The law has to be abstract and general, and the judge independent (tenured) to be able to resist the power of the other branches (for instance, the King), which could try to force the judge to decide in a way that pleases the King. In the case of the CC, the point is different, and I need to be clear about that: the CC is a co-legislator and if the CC is not legally and de facto independent from the political (elected) branches, the CC cannot be a counter-power and its function would evaporate.

- 35.

P. 17; “Il ne suffit pas qu’il y ait, dans une monarchie, des rangs intermédiaires; il faut encore un dépôt de lois. Ce dépôt ne peut être que dans les corps politiques, qui annoncent les lois lorsqu’elles sont faites et les rappellent lorsqu’on les oublie.” Montesquieu was referring at the practice of enregistrement des ordonnances royales and to the remontrances of the Parlements d’ancien régime. See Flammermont (1898).

- 36.

I’m avoiding the ambiguous word power, but if we understand the exercise of a function as an ability of doing, a power that can be entrusted to different organs or agencies, it is possible to speak of legislative power as the equivalent of the exercise of this paramount function. What matters is to take seriously the split of the legislative sovereign function/power among three independent branches—the point that Madison derived from the “celebrated” Montesquieu and that he adapted to his “republican” (elective) government with two Houses and the President exercising legislative veto.

- 37.

- 38.

«Séparation des pouvoirs», Dictionnaire électronique Montesquieu (2013): http://dictionnaire-montesquieu.ens-lyon.fr/index.php?id=286

- 39.

This idea is already in the text by Kelsen of 1928, and repeated in his answer to Schmitt (Kelsen 2008).

- 40.

- 41.

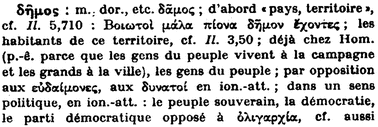

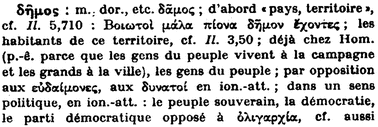

See Chantraine (1970: 273):

- 42.

The reform of the French constitution that, starting from 2010, introduced a mechanism of constitutional adjudication of enacted statutes is probably the most important sign of the expansion of the constitutional democracy (Pasquino 2009b).

- 43.

To be more precise, the Aristotelian mixed politeia was a form of government combining elements of two bad forms: oligarchy and democracy. Aristocracy was a good but ideal form, of limited interest for him because of its ideal character.

- 44.

Alito was born to Italian-American immigrants.

- 45.

Sotomayor was born in The Bronx, New York City, and is of Puerto Rican descent. Her father, who had a third-grade education, did not speak English, died when she was nine, and she was subsequently raised by her mother a telephone operator and then a practical nurse (Wikipedia). Antonin Scalia is the son of a Sicilian immigrant. Clarence Thomas was the second of three children born to M.C. Thomas, a farm worker, and Leola Williams, a domestic worker. They were descendants of American slaves, and the family spoke Gullah as a first language (Wikipedia).

- 46.

If one uses this type of rhetoric, it is difficult to understand why the US members of the Senate would be less aristocratic than the judges who exercise judicial review. It is more persuasive and less rhetorical to speak as I do of non-elected, non-accountable public officials.

- 47.

This was the Marxist preoccupation, following the radical model of the French Revolution according to which the Third Estate was all, and Marx was at the same time against the capitalist oligarchs and against the mixed government somehow revived by the social-democrats.

- 48.

Qualifying as Schmittians the authors who criticize constitutional adjudication is not an easy rhetorical trick to disqualify them; this effortless and commonly used strategy is not what I need in my justificatory theory to show that they are wrong. It is just “to give to Caesar what is Caesar’s.” I know C. Schmitt’s theoretical work well enough to consider disqualifying the reference to his theses and arguments. Even though his answers were often wrong, like the presidential role in the constitution, which American colleagues like Vermuele and Posner (2010) seem to appreciate, his questions are in many cases still with us.

- 49.

- 50.

The case of conflict among the central state organs. (See the decision of the It.CC concerning the conflict between the justice minister Mancuso and the Parliament: http://www.giurcost.org/decisioni/1996/0007s-96.htm)

- 51.

English translation on the website of the French Constitutional Council.

- 52.

Starting famously Hume (1748).

- 53.

Hobbes (1651: Ch. XXX): “The office of the sovereign, be it a monarch or an assembly, consisteth in the end for which he was trusted with the sovereign power, namely the procuration of the safety of the people, to which he is obliged by the law of nature […] But by safety here is not meant a bare preservation, but also all other contentments of life, which every man by lawful industry, without danger or hurt to the Commonwealth, shall acquire to himself..”

- 54.

- 55.

On Hobbes’ method, the following passage from the Preface to the 1647 edition of the De cive is relevant: “Concerning my method, I thought it not sufficient to use a plain and evident style in what I have to deliver, except I took my beginning from the very matter of civil government, and thence proceeded to its generation, and form, and the first beginning of justice; for everything is best understood by its constitutive causes. For as in a watch, or some such small engine, the matter, figure, and motion of the wheels cannot well be known, except it be taken in sunder, and viewed in parts; so to make a more curious search into the rights of states, and duties of subjects, it is necessary (I say not to take them in sunder, but yet that) they be so considered, as if they were dissolved.”

- 56.

I do not need to suppose any natural rights, just those established in a liberal–democratic constitution like the American or the German ones.

- 57.

I do not know of anyone who claims that the representative majority can do whatever it wants (which means a clear rejection of the axiom called “neutrality” of May’s theorem justifying majority rule!). May (1952). The supporters of majoritarian democracy have to suppose that periodical elections and perhaps bicameralism are sufficient mechanisms to guarantee the protection of fundamental rights , though both weak protection mechanisms. Bicameralism with absolute veto power of the two houses in a political system dominated by one political party is of some ambiguous help only if, like in presidential systems, divided government is possible. I speak of ambiguous help since this type of system can produce serious gridlock. (The English classical bicameralism with a House of Lords is an effective anti-despotic device, but presupposes a pre-modern, non-equalitarian society.) Elections are certainly an instrument of moderation of the power of the majority of representatives, but only for those who can produce an alternative majority; they can be called pivotal voters.

- 58.

“The Fourth Amendment [of the Hungarian Constitution], adopted 11 March 2013, prohibits the Constitutional Court from examining the substantive constitutionality of future proposed amendments to the Constitution and strips the Court of the right to refer in its rulings to legal decisions made prior to January 2012, when the new constitution came into effect” (from the website of the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute).

- 59.

“Vous avez juridiquement tort car vous êtes politiquement minoritaires.” This sentence was addressed to the conservatives in the National Legislative Assembly by the socialist MP André Laigniel in 1981 at the time of the debates concerning the nationalizations.

- 60.

On majority and truth, see Pasquino (2010).

- 61.

New York Senator Charles Schumer once said during the hearings for a nominee at the USSC: “You will decide about our life and death” (abortion and euthanasia, and now we could add marriage).

- 62.

“If it be said that the legislative body are themselves the constitutional judges of their own powers, and that the construction they put upon them is conclusive upon the other departments, it may be answered, that this cannot be the natural presumption, where it is not to be collected from any particular provisions in the Constitution. It is not otherwise to be supposed, that the Constitution could intend to enable the representatives of the people to substitute their will to that of their constituents. It is far more rational to suppose, that the courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature, in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority.” Montesquieu attributed a crucial role to the corps intermédiaires in his theory of limited/moderated government (see Mosher 2001: 183).

- 63.

- 64.

Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. (6 Pet.) 515 (1832).

- 65.

Sentenza n. 826/1988 and sentenza 466/2002.

- 66.

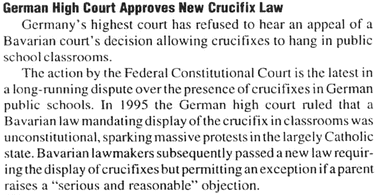

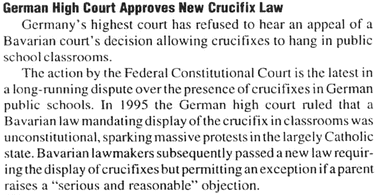

BVerfG 1995b: 2477. After that decision though:

- 67.

In any event, the parliament can overrule a decision of the constitutional court amending the constitution. An interesting example is the amendment of the Italian constitution overruling a sentence of the It. CC concerning rules of criminal procedure: the Sentenza 361/1998 canceling art. 513 of the criminal code modified by a statute of August 7th 1997, n. 267, was indeed overridden by the amendment of art. 111 of the Italian constitution passed on November 23rd 1999.

- 68.

For examples in contexts other than US constitutional history, see J. Ferejohn & P. Pasquino, The Countermajoritarian Opportunity, 13 (2010) U. PA. J. CONST. L. 353–395.

References

Arndt, Adolf. 1976. Politische Reden und Schriften. Berlin/Bad Godesberg: Dietz.

Barthélemy, Joseph. 1906. Le rôle du pouvoir exécutif dans les républiques modernes. Paris: Giard et Brière.

Blythe, James. 1992. Ideal Government and the Mixed Constitution in the Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cappelletti, Mario. 1984. Giudici Legislatori? Milano: Giuffrè.

Chantraine, Pierre. 1970. Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque. Histoire des mots. Paris: Klincksieck.

Cheli, Enzo. 1961. Atto politico e funzione d’indirizzo politico. Milano: Giuffrè.

Cohen, M., and P. Pasquino. 2013. La motivation des décisions de justice. Le cas des cours souveraines et constitutionnelles. Paris: Rapport pour le Ministère de la Justice.

Dahl, Robert. 1989. Democracy and Its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Eisenmann, Charles. 2002. Essais de théorie du droit, de droit constitutionnel et d’idées politiques. Paris: LGDJ. [notably: « L’esprit des Lois et la séparation des pouvoirs », originally published in Mélanges Carré de Malberg. Paris: Libr. du Recueil Sirey.].

Ferejohn, John, and Pasquale Pasquino. 2010. The Countermajoritarian Opportunity. University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law 13: 353–395.

Flammermont, Jules. 1898. Remontrances du Parlement de Paris au XVIII e siècle. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

Gardbaum, Stephen. 2013. The Commonwealth Model of Constitutionalism. Theory and Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ginsburg, Thomas. 2003. Judicial Review in New Democracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goldoni, Marco. 2009. La dottrina costituzionale di Sieyès. Firenze: Firenze University Press.

———. 2012. At the Origins of Constitutional Review: Sieyès’ Constitutional Jury and the Taming of Constituent Power. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 32 (2): 211–234.

Hobbes, Thomas. 1651. Leviathan.

Hume, David. 1748. Of the Original Contract.

Kaufmann, Erich. 1909. Auswärtige Gewalt und Kolonialgewalt in der Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika: Eine rechtsvergleichende Studie über die Grundlagen des amerikanischen und deutschen Verfassungsrecht. Leipzig: Duncker and Humblot.

Kelsen, Hans. 1928. La garantie juridictionnelle de la constitution. Revue de droit public 44: 197.

———. 1945. General Theory of Law and State. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

———. 2008 [1931]. Wer soll der Hüter der Verfassung sein? Berlin: Mohr Siebeck.

———. 2013. The Essence and Value of Democracy. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Kramer, Larry. 2004. The People Themselves: Popular Constitutionalism and Judicial Review. New York: Oxford University Press.

Landi, Lando. 1981. L’Inghilterra e il pensiero politico di Montesquieu. Padova: CEDAM.

Le Divellec, Armel. 2007. Le gardien de la constitution de Carl Schmitt. In La controverse sur « le gardien de la Constitution » et la justice constitutionnelle. Kelsen contre Schmitt – Der Weimarer Streit um den Hüter der Verfassung und die Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit, Kelsen gegen Schmitt, ed. P. Pasquino and Olivier Beaud, 33–78. Paris: Editions Panthéon Assas.

Lloyd, Sharon. 2014. Hobbes’s Moral and Political Philosophy. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/hobbes-moral/

Machiavelli, Niccolo. 1989. The Chief Works and Others. Vol. 1, 101–115. Durham: Duke University Press.

Manin, Bernard. 1989. Montesquieu. In A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution, ed. F. Furet and M. Ozouf. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

May, Kenneth O. 1952. A set of independent necessary and sufficient conditions for simple majority decisions. Econometrica 20: 680–684.

Mosher, M.A. 2001. Monarchy’s Paradox: Honor in Face of Sovereignty. In Montesquieu’s Science of Politics. Essays on The Spirit of Laws. New York: Rowman & Littlefield.

Necker, Jacques. 1792. Du pouvoir exécutif dans les grands États, 2 vols.

Nippel, Wilfried. 1980. Mischverfassungstheorie und Verfassungsrealität in Antike und früher Neuzeit. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

Parfit, Derek. 1986. Reasons and Persons. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pasquino, Pasquale. 1994a. Gardien de la constitution ou justice constitutionnelle? C. Schmitt et H. Kelsen. In 1789 et l’invention de la constitution, ed. M. Troper and L. Jaume, 141–152. Paris: Bruylant – L.G.D.J.

———. 1994b. Thomas Hobbes. La condition naturelle de l’humanité. Revue Française de Science Politique 44: 294–307.

———. 1996. Political Theory, Order and Threat. In Nomos XXXVIII: Political Order, 19–40. New York: NYU Press.

———. 1998a. Sieyes et l’invention de la constitution en France. Paris: Odile Jacob.

———. 1998b. Locke on King’s Prerogative. Political Theory 26 (2): 198–208.

———. 1998c. Constitutional Adjudication and Democracy. Comparative Perspectives: USA, France, Italy. Ratio Juris 11: 38–50.

———. 2000. Th. Hobbes: la condition légale dans le Commonwealth. Cahiers de Philosophie de l’Université de Caen 34: 147–164.

———. 2001a. One and Three: Separation of Powers and the Independence of the Judiciary in the Italian Constitution. In Constitutional Culture and Democratic Rule, ed. J. Ferejohn, J. Rakove, and J. Riley, 205–222. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2001b. Hobbes, Religion and Rational Choice. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 82: 406–419.

———. 2006a. L’origine du contrôle de constitutionnalité en Italie: Les débats de l’Assemblée constituante (1946–47). Rivista trimestrale di diritto pubblico 1: 1–11.

———. 2006b. Voter et juger: La démocratie et les droits. In L’architecture du droit. Mélanges en l’honneur de Michel Troper, 775–787. Paris: Economica.

———. 2009a. Machiavelli and Aristotle: The Anatomies of the City. History of European Ideas 35: 397–407.

———. 2009b. The New Constitutional Adjudication in France. The Reform of the Referral to the French Constitutional Council in Light of the Italian Model. Indian Journal of Constitutional Law 3: 105–117.

———. 2010. Samuel Pufendorf: Majority Rule (Logic, Justification and Limits) and Forms of Government. Social Science Information, (Collective Decision Making Rules) 49: 99–109.

———. 2012. Classifying Constitutions: Preliminary Conceptual Analysis. Cardozo Law Review 34: 999–1019.

———. 2013a. Democracy: Ancient and Modern, Good and Bad. In Democracy in a Russian Mirror, ed. A. Przeworski, 99–118. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2013b. Majority Rules in Constitutional Democracies. Some Remarks About Theory and Practice. In Majority Decisions, ed. Stéphanie Novak and Jon Elster, 134–156. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2015. Disclosed and Undisclosed Voting in Constitutional/Supreme Courts. In Secercy and Publicity in Votes and Debates, ed. Jon Elster. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Przeworski, Adam. 1999. Minimalist Conception of Democracy. A Defense. In Democracy’s Value, ed. I. Shapiro and C. Hacker-Cordon, 23–55. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

———. 2011. Democracy and the Limits of Self-Government. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sartori, Giovanni. 1987. The Theory of Democracy Revisited. Chatham: Chatham House.

Schmitt, Carl. 1931. Der Hüter der Verfassung. Berlin: Dunker and Humblot.

Shapiro, Martin. 1981. Courts: A Comparative and Political Analysis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Simon, H. 1994. Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit. In Handbuch des Verfassungsrechts, ed. E. Benda, H. Maierhofer, and W. Vogel, 1637–1681. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Smend, Rudolf. 1923. Die politische Gewalt in Verfassungsstaat und das Problem der Staatform. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr (P. Siebeck).

Strauss, Leo. 1995 [1932]. Notes on Carl Schmitt, The Concept of Political. Trans J. Harvey Lomax. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Strawson, P.F. 1959. Individuals – An Essay in Descriptive Metaphysics. London: Methuen.

Sutter, Daniel. 1997. Enforcing Constitutional Constraints. Constitutional Political Economy 8: 139.

The New Encyclopedia Britannica. 1993. Micropaedia, 15th ed. Vol. 4. Macmillan: New York.

Tushnet, Mark. 1999. Taking the Constitution Away from the Courts. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Vermuele, Adrian. 2011. Second Opinions and Institutional Design. Virginia Law Review 97: 1435.

Vermuele, Adrian, and Eric Posner. 2010. The Executive Unbound: After the Madisonian Republic. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vinx, Lars. 2015. The Guardian of the Constitution. Hans Kelsen and Carl Schmitt on the Limits of Constitutional Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Von Bruneck, A. 1988. Constitutional Review and Legislation in Western Democracies. In Constitutional Review and Legislation: An International Comparison, ed. C. Landfried. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

Waldron, Jeremy. 1999. Law and Disagreement. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weiler, J.H.H. 2011. In The Worlds of European Constitutionalism, ed. G. de Burca and J.H.H. Weiler. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Zakaria, Fareed. 2003. The Future of Freedom: Illiberal Democracy at Home and Abroad. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pasquino, P. (2018). A Political Theory of Constitutional Democracy: On Legitimacy of Constitutional Courts in Stable Liberal Democracies. In: Christiano, T., Creppell, I., Knight, J. (eds) Morality, Governance, and Social Institutions. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61070-2_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-61070-2_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-61069-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-61070-2

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)