Abstract

In this work, we study how legislation can be published as open data using semantic web technologies. We focus on Greek legislation and show how it can be modeled using ontologies expressed in OWL and RDF, and queried using SPARQL. To demonstrate the applicability and usefulness of our approach, we develop a web application, called Nomothesia, which makes Greek legislation easily accessible to the public. Nomothesia offers advanced services for retrieving and querying Greek legislation and is intended for citizens through intuitive presentational views and search interfaces, but also for application developers that would like to consume content through two web services: a SPARQL endpoint and a RESTful API. Opening up legislation in this way is a great leap towards making governments accountable to citizens and increasing transparency.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Legislative knowledge representation

- Linked Open Data

- Public services

- CEN MetaLex

- European Legislation Identifier

1 Introduction

Recently, there has been an increased interest in making government data open and easily accessible to the public. Technological advances in the area of the semantic web have given rise to the development of the so-called Web of Data, which has given an even stronger push to such efforts. The research area of linked data studies how data that are expressed in RDF will be available on the Web and interconnected with other data with the aim of increasing its value for everybody. Therefore, semantic web and linked data provide a set of technologies for making government data open [16].

An important kind of government data is the data related to legislation. Legislation applies to every aspect of people’s living and evolves continuously building a huge network of interlinked legal documents. Therefore, it is important for a government to offer services that make legislation easily accessible to the public aiming at informing them, enabling them to defend their rights, or to use legislation as part of their job. Towards this direction, there are already many European Union (EU) countries that have computerized the legislative process by developing platforms for archiving legislation documents and offering on-line access to them.

In Greece, so far, there has been a limited degree of computerization of the legislative process and even the discovery of legislation related to a specific topic can be a hard task. The legislative work of the Greek government has been published since 1907 in the form of a gazette by the National Printing Office (http://www.et.gr/). Legislation is published on a daily basis in that gazette and it is distributed only in a PDF file format. A small step for making Greek legislation more accessible to the public has been made by Diavgei@ (https://diavgeia.gov.gr/), a Greek program introduced in 2010, enforcing transparency over government and public administration by requiring that government and public administration have to upload their decisions on the Web. However, no common file format is enforced nor any structuring of their textual content.

In this work, we are following the footsteps of other successful efforts in Europe and aim at modernizing the way Greek legislation is made public. We envision a new state of affairs in which ordinary citizens have advanced search capabilities at their fingertips on the content of legislation. We also envision that legislation is published in a way so that developers can consume it, and so that it can be also combined with other open data to increase its value for interested people. Currently, there is no other effort in Greece that takes this perspective on legislation and related decisions made by government institutions and administration alike.

Technically, we view legislation as a collection of legal documents with a standard structure. Legal documents may be linked in complex ways. A legal document might refer to another legal document or it may modify the content of other legal documents. As a result, a complex semantic structure arises from legal documents and their interrelationships. Our aim is to develop intelligent services that not only present the textual content of legal documents but are able to answer complex analytics such as “Which are the 5 most frequently modified legal documents during 2008–2013?” or “Who are the 3 past government members that have signed the most legal documents during their service in 2008–2015?”. In addition, we would like to be able to interlink legislation with other linked data sources (e.g., the administrative geography of Greece) so that queries like “Which legal documents refer to geographical areas that belong to the region of Macedonia-Thrace and have population more than 100,000?” can be posed.

Contributions. Our contributions towards achieving the aforementioned goals are summarized as follows.

We follow the latest European standards and best practices and develop an OWL ontology, called Nomothesia ontology (Nomothesia means legislation in Greek), for modeling the content of Greek legislation documents. The first benefit of this approach is the formulation of rich queries over the content of Greek legislation. The second one is the representation of legislative modifications which enables tracking of the evolution of a legislative document and compact storage of its content in the form of differences (i.e., deltas in the jargon of version control).

We build a tool tailored to the particularities of Greek legislation for populating Nomothesia ontology with all issues of the government gazette during 2006–2015 and linking the resulting dataset with DBpedia and the datasets Greek Administrative Geography and Greek Public Buildings (http://linkedopendata.gr/). Overall, the tool processed 2,676 legal documents and stored approximately 1,85M RDF triples. This is the first time such a substantial part of the legislative corpus of Greece is organized in this manner, linked with external sources, and made publicly available.

We develop a prototype web application, called Nomothesia, that offers advanced presentational views, search, and analytics functionality over Greek legislation. Among others, one may view how legal documents evolve through time in response to amendments, retrieve a piece of legislation in various formats, and search for legislative documents based on their metadata or textual content. Moreover, Nomothesia offers a SPARQL endpoint and a RESTful API which enable the formulation of complex queries, such as the ones presented previously.

Organization. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses related work in legislative knowledge representation using semantic web technologies. Section 3 gives background information on the structure and encoding of Greek legislation. Section 4 presents Nomothesia ontology that is developed for the modeling of Greek legislation, the challenges faced in populating it based on a large part of Greek legislation corpus, and discusses interlinking with other publicly available open data. Section 5 gives examples of the RDF representation of two real legal documents according to Nomothesia ontology and demonstrates how the resulting data can be queried using SPARQL. Section 6 presents the Nomothesia web platform. Section 7 presents preliminary user feedback on Nomothesia. Last, Sect. 8 summarizes our contributions and discusses future work.

2 Related Work

Modernization of the way citizens access legislation has been a primary concern of many governments across the world. The development of information systems archiving the content and metadata of legal documents has been a common practice towards making legislation easily accessible to the public [5]. To name a few examples, the MetaLex document server [11] (http://doc.metalex.eu/) offers Dutch national regulations published by the official portal of the Dutch government, while the United Kingdom publishes legislation on its official portal (http://www.legislation.gov.uk/). In the same spirit, [9] presents a service that offers Finnish legislation as linked data. Last, the Publications Office of the EU has developed a central content and metadata repository, called CELLAR, for storing official publications and bibliographic resources produced by the institutions of the EU [8]. The content of CELLAR, which includes EU legislation, is made publicly available by the EUR-lex service (http://eur-lex.europa.eu).

All of the above endeavors adopt semantic web technologies for modeling, querying, and making legislative content easily accessible to the public. The adoption of web standards like XML, RDF, SPARQL as well as common practices for publishing such data as linked data has been a common practice among these efforts in the design of vocabularies and ontologies for legislative documents. One such vocabulary is the XML schema Akoma Ntoso (http://www.akomantoso.org/), which was funded by the United Nations for publishing African parliamentary proceedings and supporting legislative documentation in parliaments [2]. Another one is MetaLex [3], which was originally proposed as an XML vocabulary for the encoding of the structure and content of legislative documents, but updated later on with functionality related to timekeeping and version management [4]. After its adoption by the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) [7], MetaLex evolved to an OWL ontology called CEN MetaLex (in the following just MetaLex). More recently, the European Council introduced the European Legislation Identifier (ELI) [6] as a new common framework that has to be adopted by the national legal publishing systems in order to unify and link national legislation with European legislation. ELI, as a framework, proposes a URI template for the identification of legal resources on the web and it also provides an OWL ontology, which is used for expressing metadata of legal documents and legal events. ELI, like Akomo Ntoso and MetaLex, is not a one-size-fit-all model but it has to be extended to capture the particularities of national legislation systems.

Both Akoma Ntoso and MetaLex have been the keystones for the adoption of relevant practices in the legal domain. Akoma Ntoso has been the vocabulary of choice for the development of the XML schemata LegalDocML [14] and LegalRuleML [1] that aim to offer vocabularies for the modeling and representation of legal documents as well as reasoning capabilities with respect to the normative rules appearing in such documents. MetaLex was extended in the context of EU Project ESTRELLA (http://www.estrellaproject.org/) which developed the Legal Knowledge Interchange Format (LKIF) [12]. LKIF is an ontology for modeling both legal and legislative concepts that mainly express structure, content, and events regarding the process of legislation. In the same spirit, the European Case Law Identifier (ECLI), a sister endeavor of ELI, was introduced recently for modeling case laws [13].

The present work follows in the footsteps of the aforementioned efforts by offering to citizens a prototype system through which they may browse, search, and query Greek legislation. Similar to other efforts, the system is based on semantic web technologies; it offers an OWL ontology that extends MetaLex and ELI and is linked with DBpedia and two Greek linked geospatial datasets.

3 Background on Greek Legislation

Greek legislation is published through different types of documents depending on the government body enacting the legislation. Each piece of legislation has a standardized structure and follows an appropriate encoding. Both of these aspects are discussed in detail below.

3.1 Types and Encoding of Greek Legislation

The encoding of Greek legislation follows the rules set out in the document “Manual Directives for the encoding of legislation”, which has been issued by the Greek Central Committee of Encoding Standards and has been legislated in Law 2003/3133. In this work we are considering the encoding of five primary sources (types) of Greek legislation: constitution, presidential decrees, laws, acts of ministerial cabinet, and ministerial decisions. We also consider two secondary sources of Greek legislation: legislative acts and regulatory provisions. These sources of legislation are materialized in legal documents (see Fig. 1 for an example) that adhere to a typical structure organized in a tree hierarchy around the concept of fragments (divisions).

Articles are the basic units in the main body of a legal document, numbered using Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, ...). An article may consist of a list of paragraphs that are numbered using Arabic numerals as well. Paragraphs may have a list of indents (cases). Indents are numbered using lower-case Greek letters (\(\alpha \), \(\beta \), \(\gamma \), ...) and may have sub-indents which are numbered using double lower-case Greek letters (\(\alpha \alpha \), \(\beta \beta \), \(\gamma \gamma \), ...). Passages are the elementary fragments of legal documents and are written contiguously, i.e., without any line breaks between them. Passages are the building blocks of indents and paragraphs. The main body of legal documents may be subdivided according to their size in larger units, such as sections, chapters, parts or books, which are numbered using upper-case Greek letters. Larger units and articles may have a title, which must be general and concise in order to reflect their content, and is used in the systematic classification of the substance of legal documents.

3.2 Metadata of Greek Legislation

In addition to the aforementioned structural elements, legal documents are accompanied by metadata. This primarily includes the title of the legal document, which must be general enough but concise so as to reflect its content, the type (e.g., Law, Presidential Decree), the year of publication, which can be inferred by the publication date, and the serial number. These latter elements (type, year, number) of metadata information serve also as a unique identifier of the legal document. Of equal importance are also the issue and the sheet number of the government gazette in which the legal document is published.

When reference to other legislation or public administration decisions is necessary, this is done with citations. For purposes of accuracy, citations must include the type of the legal document, its number, and its year of publication.

There is a large number of secondary metadata information, which could be related to a legal document. Currently in our model we consider three types of such metadata (named entities): the signatories (government members) that introduced the legislation, the administrative areas (locations), and the organizations mentioned in the text.

3.3 Legislative Modifications

Legislation is an event-driven process. Legal documents are passed based on an appropriate legislative procedure and then published in the government gazette. They may be modified by later legal documents with respect to their content (amendments) or they may be repealed (see Fig. 2). In the course of this process, we need to capture the structure of a legal document and the evolution of its content through time, given by the legislative modifications applied on the primary legal document or its versional successors. Although there is a standard encoding of Greek legislation (as presented in Sect. 3.1), there is no standard encoding for the codification of amendments or repeals. This is a challenge for any work [4, 10] like ours to which we offer the following solution.

By the analysis of a large corpus of Greek legislation and the consultation of Greek government officials, we have defined three main types of legislative modifications: insertion, repeal, and substitution. All three operations are applied with respect to an enacted and published legal document and an enacted but not yet published one. We explain these operations below and refer to the two documents by the identifiers \(\mathbf {D1}\) and \(\mathbf {D2}\), respectively.

Insertion. Document \(\mathbf {D2}\) specifies the exact structure and content of a new fragment that is to be inserted verbatim at a certain place of document \(\mathbf {D1}\).

Repeal. Document \(\mathbf {D2}\) revokes a specific fragment of document \(\mathbf {D1}\).

Substitution. Document \(\mathbf {D2}\) specifies the exact structure and content of a new fragment as well as a fragment of document \(\mathbf {D1}\) that is to be replaced in document \(\mathbf {D1}\) by the new fragment.

These three kinds of modifications (amendments) produce new versions of the original, as enacted, legal document (see Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

4 Modeling Greek Legislation Using Semantic Web Technologies

In this section, we develop an OWL ontology for modeling the structural information of legal documents along with their accompanying metadata (i.e., title, gazette, publication date, etc.) and capturing how these documents may evolve through time in response to modifications. We call our ontology Nomothesia ontology and we discuss its current version (http://legislation.di.uoa.gr/nomothesia.owl) that adopts the ELI framework discussed in Sect. 2.

4.1 An OWL Ontology for Greek Legislation

Legal documents (LegalResource) are organized in fragments (LegalResourceSubdivision). Each legal document has (is_realized_by) subsequent versions (LegalExpression), which are differentiated by the previous ones based on (matterf) some subsequent modifications (LegislativeModification) that are referred (legislativeCompetenceGroundOf) in subsequent legal documents and affect (patient) specific fragments. A legal document (LegalResource) changes an enacted legal document, which automatically inherits a new version (LegalExpression). Legal documents also include references (BibliographicCitation), which cite (cites) other legal documents or their fragments (CitableBibliographicObject).

Most of the above concepts are adopted from the ELI ontology discussed in Sect. 2. The rest of the concepts belong to the MetaLex ontology and there are no counterparts of them in ELI. Both ELI and MetaLex describe the event-driven process of legislation. We have extended this basis to describe also the structure, the content and the metadata of Greek legal documents (see Fig. 4).

As we already mentioned in Sect. 3, Greek legal documents are organized in specific types of fragments (e.g., Article, Paragraph, Indent). Indents and passages are the bottom elements of the main body’s hierarchy, that define text (has_text). Legislative modifications are also classified in the three predefined types: Insertion, Repeal and Substitution. Given the above extensions, we can represent and store legislation natively only in the RDF format. Given the RDF encoding of a legal document, any additional format (e.g., PDF, XML) can be produced dynamically. Through this process, we eliminate the need to include special information about the different manifestations (Format) of any given legal document.

Primary metadata for identification of the legal documents are captured using both the ELI vocabulary and our own extensions: type of document (e.g., Law, Presidential Decree), title (title), serial number (id_local), date of publication (date_publication) and the Gazette issue (Gazette) in which a legal document has been published (published_in). We also capture a few secondary metadata (named entities) such as: signatories (Signatory), that is, the government members who signed (passed_by) a legal document, and possibly an administrative area (AdministrativeArea) or an organization (Organization) referred in (relevant_for) the document. There is also the appropriate means for the classification (is_about) of legal documents or divisions. As European legislation is adopted in Greek legislation, we should link the ELI URIs of directives, that are adopted (transposes) by national legal documents.

4.2 Persistent URIs in Nomothesia

In order to identify legal resources, we need appropriate URIs. Persistent URIs is a strong recommendation by EU [15] according to ELI. It is very important to have reliable means to identify legal documents, their fragments and generally any aspect related with a legal document. In Nomothesia, we structure the persistent URIs of legal documents according to template http://legislation.di.uoa.gr/eli/type/year/id. This pattern serves as a unique URI for each legal document based on its individual information: type of legislation (e.g., pd is the abbreviation for Presidential Decree), year of publication, and identifier (serial number). For example, the URI for Presidential Decree 54/2011 is http://legislation.di.uoa.gr/eli/pd/2011/54.

Extending the basic URI of a legal document, we have URI extensions for its version. We define three different types: original (as enacted); current and chronological version given in the ISO 8601 format “YYYY-MM-DD”. To retrieve Law 2014/4225 as of 21/10/2015, we use URI http://legislation.di.uoa.gr/eli/law/2014/4225/2015-10-21. Moving a step forward, we extend the versional URIs to capture the available manifestations of its version (e.g., PDF, XML, JSON). Despite the fact that our ontology does not capture such information, our RESTful API will serve such commodities, producing the appropriate representations on-the-fly. Through an HTTP GET request, an agent may request the JSON format of the enacted version of Ministerial Decision 2015/240 using URI http://legislation.di.uoa.gr/eli/md/2015/240/enacted/data.json. We can also refer to specific fragments of a legal document, following its nested structure from the top fragment level to our own point of interest. For instance, to refer to the first paragraph of the second article of Act of Ministerial Cabinet 2013/10 (as enacted version), we use URI http://legislation.di.uoa.gr/eli/pd/2013/10/article/2/paragraph/1.

4.3 Population of Nomothesia Ontology

Population of Nomothesia ontology proved to be a demanding task that led us develop a tool tailored to the particularities of Greek legislation. We next list some of the challenges we faced, which highlight the need for an advanced computerized legislative system in Greece. First, the government gazette is only made available in PDF format and follows a two-column layout. It is well-known that transformation of PDF documents into plain text, written in a non Latin alphabet is error-prone. Second, although the encoding of Greek legislation is standardized, there are many instances of Greek legislation that do not conform with this encoding. This is mainly due to human errors during the typing process, a fact that contributes to the fragility of the task of ontology population. Third, recognition of legislative modifications is even more intricate taking into account the lack of a standard encoding for the codification of amendments or repeals.

To deal with the above challenges, we built the Greek Government Gazette Parser (G3 Parser), which is a rule-based parsing tool designed to be flexible and robust towards frequent errors during the typing process of a legislative document, common deviations from the encoding of Greek legislation (see Sect. 3), as well as recognition of certain phrases denoting amendments and repeals (see Sect. 3.3). We successfully applied G3 Parser in almost all gazette issues during 2006–2015 (corresponding to 2,676 legal documents) producing approximately 1,85M RDF triples. The various stages of G3 Parser can be described as follows. (a) Transformation of double column PDF documents (gazette issues) in one-column plain text. (b) Split of text in individual legislative documents using appropriate regular expressions. (c) Parsing of the beginning of each legislative document for extracting primary metadata (i.e., title, issue number, etc.) and producing the corresponding RDF triples. (d) Parsing of the rest of the textual content of the document following a context free-grammar expressing the encoding of Greek legislation as described in Sect. 3. During this stage, G3 Parser is able to organize the textual content into fragments (e.g., articles and their cases, paragraphs, and passages) and generate the corresponding RDF triples following Nomothesia ontology. (e) Extraction of additional information from the bottom-level fragments (i.e., passages), like citations, legislative modifications, and named entities.

4.4 Linking Legislation with Other Open Data

The textual content of Greek legislation is very rich in references to named entities of three kinds: persons, places, and organizations. Nomothesia is able to capture these references and link them with the corresponding entities found in other public data sets, which provide additional information about them. To achieve this, for each of the above three kinds of entities, Nomothesia consults, respectively, the datasets of Greek DBpedia (http://el.dbpedia.org/), Greek Administrative Geography, and Greek Public Buildings. The last two datasets are part of a broader initiative started in the University of Athens for expressing various Greek geospatial data in RDF and publishing them as linked data on the Greek Linked Open Data portal (http://linkedopendata.gr/dataset).

As mentioned in the previous section, Stage (e) of G3 Parser is responsible for recognizing these entities. For each entity type and its corresponding dataset, G3 Parser has access to an inverted index, implemented using Apache Lucene (https://lucene.apache.org/), that associates the textual description of entities of this type with their corresponding URI. For example, there is an inverted index for entities of type dbpedia-owl:Person associating the lexical value of property prop-el:name to their URI. While in Stage (e), G3 Parser is able to recognize proper nouns and perform lookups on each one of the inverted indices. Whenever a lookup is successful over the inverted index for persons, G3 Parser creates a new entity linking it with the corresponding URI of DBpedia. On the other hand, if there is a successful lookup for a place or organization name, G3 Parser generates an RDF triple of the form \(\langle duri, \textsf {eli:relevant\_for}, euri \rangle \) where duri and euri correspond to the URIs of the current legislation document and named entity, respectively. As it is demonstrated in Sect. 5.3, interlinking Greek legislation with other relevant datasets allows for the formulation of sophisticated queries by indirectly accessing the additional information provided by these datasets.

5 Modeling Greek Legislation Using Nomothesia: A Short Example

In this section we give an example of how Nomothesia could be used to model Greek legislation. The example employs two legal documents, Presidential Decree 2011/54 and Presidential Decree 2012/10.

5.1 Representing P.D. 2011/54 in RDF

P.D. 2011/54 (see Fig. 1) is a Presidential Decree, which comes as a subclass of Legal Resource. It consists of 6 articles, each of which has its own nested subdivisions (paragraphs, passages, etc.). There are also primary metadata (title, publication date, etc.) related with the specific resource (see Fig. 5).

5.2 Capturing the Legislative Interaction between P.D. 2011/54 and P.D. 2012/10

P.D. 2012/10 (see Fig. 2) is a subsequent legal document that changes P.D. 2011/54 by applying legislative modifications to produce a new version that realizes the specific legal document. The legislative modifications are of a specific type (Insertion, Substitution). They have a specific structure and they refer to a specific part of the precedent legal document, which acts as the patient of the legislative modification (see Fig. 6).

5.3 Linking P.D. 2011/54 with Greek administration Geography

Document P.D. 211/54 refers to multiple named entities related to administrative divisions and rivers. In this example, we demonstrate linking of this document with the geographical entity of Greek Administrative Geography corresponding to the subdistrict of Evros (see Fig. 7).

5.4 Querying the Resulting RDF Data Using SPARQL

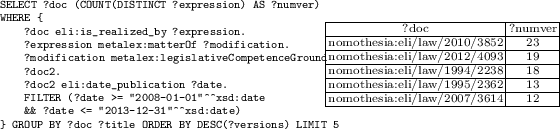

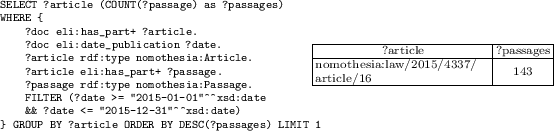

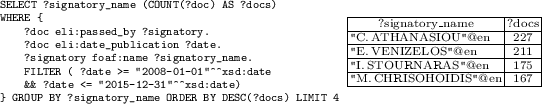

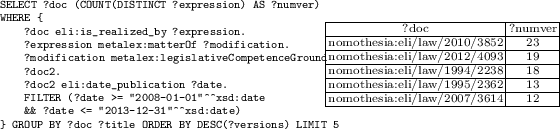

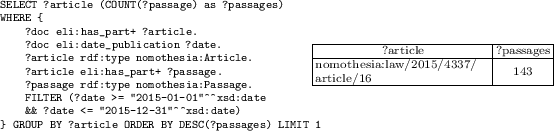

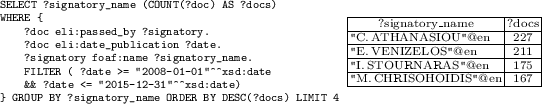

Based on the above, we have the ability to pose queries on the resulting RDF graph. Three queries are given in natural language together with their expression in SPARQL.

The above queries are simple examples of the high level expressiveness (see Sect. 4) we can apply on Greek legislation, because we recorded a minimum number (only two) of legal documents in our example. Based on the above representation, we could build and present the current version of P.D. 2011/54 (see Fig. 3) through an automated process.

6 The Nomothesia Web Platform and RESTful API

We have implemented a web platform, using Java Spring framework, called Nomothesia (http://legislation.di.uoa.gr), which publishes legislation on the web. Legal documents are stored in RDF, using Sesame RDF store. Nomothesia comes with an intuitive interface for presenting legal documents. Among other capabilities, one may view how a certain legal document has evolved through time in response to modifications; view the actual modifications highlighted, or view the state of a legal document at a certain time point by applying all modifications to the initial document. With respect to search, Nomothesia offers an advanced search interface over the metadata of a legal document (e.g., title, enactment date) and the textual content of its structural elements. There are also pages presenting interesting statistics.

Last, Nomothesia offers a RESTful API serving legal documents in various formats (e.g., XML, JSON) and a SPARQL endpoint that can be used by more advanced users to form complex queries and easily retrieve and access legal documents as web resources. The latter functionality gives the opportunity to a programmer for direct open access to the knowledge base of Nomothesia, which can be employed to consume the legislative work of government into applications and combine it with other resources on the web so as to increase its value. Therefore, third party developers can build applications that utilize legislation for societal and business interests.

6.1 Querying Legislation Using SPARQL

Using Nomothesia SPARQL endpoint, we can answer complex queries as the following.

-

Retrieve the 5 most frequently modified legal documents during 2008–2013.

-

Retrieve the longest article that has been published in 2015.

-

Find the 3 post government members that have signed the most legal documents during their service in 2008–2015.

7 Preliminary Feedback on Nomothesia

Nomothesia is a research prototype and it is still not well-known to the public. Thus, we have currently received limited feedback from our main target group, the citizens. In April of 2016, Nomothesia was presented and received an award in the 1st IT4GOV Contest, which was organized by the Greek Ministry of Administrative Reform & Electronic Governance. Among the contest jury members were 3 ministers and people from the industry, who judged Nomothesia positively. Following this contest, we have been in contact with officials from the House of Parliament and the Ministry of Administrative Reform & Electronic Governance, who have expressed interest in deploying Nomothesia in the governmental portal.

8 Conclusions and Future Work

In this paper we presented how Greek legislation can be published as open data using semantic web technologies. Our work is based on the latest European standards. We highlighted the significance of extending those standards in order to produce a semantic national legal publishing system and capture the particularities of Greek legislation. We highlighted the importance of interlinking legislation with other publicly available open data. Finally, we demonstrated the Nomothesia web platform, SPARQL endpoint and RESTful API, which offer advanced services to both citizens and programmers.

As an initial step of our future work we would like to proceed with an evaluation of our system based on user experience and study possible improvements. As a part of functional improvements, we would like to re-engineer the existing parsing system with natural language components for document zoning and entity recognition. Another direction would be the interlinking of Greek legislation with European legislation and case laws following the European Case Law Identifier scheme. Finally, we would like to extend our ontology to capture more complex legislative modifications.

References

Athan, T., Governatori, G., Palmirani, M., Paschke, A., Wyner, A.Z.: LegalRuleML: design principles and foundations. In: Faber, W., Paschke, A. (eds.) Reasoning Web 2015. LNCS, vol. 9203, pp. 151–188. Springer, Cham (2015). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-21768-0_6

Barabucci, G., Cervone, L., Palmirani, M., Peroni, S., Vitali, F.: Multi-layer markup and ontological structures in Akoma Ntoso. In: Casanovas, P., Pagallo, U., Sartor, G., Ajani, G. (eds.) AICOL -2009. LNCS (LNAI), vol. 6237, pp. 133–149. Springer, Heidelberg (2010). doi:10.1007/978-3-642-16524-5_9

Boer, A., Hoekstra, R., Winkels, R., van Engers, T., Willaert, F.: \(^{META}lex\): legislation in XML. In: JURIX: The Fifteenth Annual Conference, London (2002)

Boer, A., Winkels, R., van Engers, T., de Maat, E.: Time and versions in \(^{META}lex\) XML. In: Proceeding of the Workshop on Legislative XML, Kobaek Strand (2004)

Casanovas, P., Palmirani, M., Peroni, S., van Engers, T.M., Vitali, F.: Semantic web for the legal domain: the next step. Semant. Web 7(3), 213–227 (2016)

ELI Task Force. ELI - A technical implementation guide (2015)

E. C. for Standardization (CEN). CEN Workshop Agreement: Metalex (Open XML Interchange Format for Legal and Legislative Resources). Technical report (2006)

Francesconi, E., Küster, M.W., Gratz, P., Thelen, S.: The ontology-based approach of the publications office of the EU for document accessibility and open data services. In: Kő, A., Francesconi, E. (eds.) EGOVIS 2015. LNCS, vol. 9265, pp. 29–39. Springer, Cham (2015). doi:10.1007/978-3-319-22389-6_3

Frosterus, M., Tuominen, J., Wahlroos, M., Hyvönen, E.: The finnish law as a linked data service. In: Cimiano, P., Fernández, M., Lopez, V., Schlobach, S., Völker, J. (eds.) ESWC 2013. LNCS, vol. 7955, pp. 289–290. Springer, Heidelberg (2013). doi:10.1007/978-3-642-41242-4_46

Hallo Carrasco, M., Martínez-González, M.M., De La Fuente Redondo, P.: Data models for version management of legislative documents. J. Inf. Sci. 39(4), 557–572 (2013)

Hoekstra, R.: The MetaLex document server – legal documents as versioned linked data. In: Aroyo, L., Welty, C., Alani, H., Taylor, J., Bernstein, A., Kagal, L., Noy, N., Blomqvist, E. (eds.) ISWC 2011. LNCS, vol. 7032, pp. 128–143. Springer, Heidelberg (2011). doi:10.1007/978-3-642-25093-4_9

Hoekstra, R., Breuker, J., Di Bello, M., Boer, A.: LKIF core: principled ontology development for the legal domain. In: Proceedings of the 2009 Conference on Law, Ontologies and the Semantic Web: Channelling the Legal Information Flood, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, pp. 21–52. IOS Press (2009)

Van Opijnen, M.: European case law identifier: indispensable asset for legal Information retrieval. In: Biasiotti, M.A., Faro, S. (eds.) From Information to Knowledge. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications, vol. 236, pp. 91–103. IOS Press (2011). doi:10.3233/978-1-60750-988-2-91. ISBN: 978-1-60750-987-5

Palmirani, M., Vitali, F.: Akoma-Ntoso for legal documents. In: Sartor, G., Palmirani, M., Francesconi, E., Biasiotti, M.A. (eds.) Legislative XML for the Semantic Web. Law, Governance and Technology Series, vol. 4, pp. 75–100. Springer, Heidelberg (2011)

Archer, P., Goedertier, S., Loutas, N.: Study on persistent URIs, with identification of best practices and recommendations on the topic for the MSs and the EC (2012)

PwC EU Services. Case study: How Linked Data is transforming eGoverment (2013)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Chalkidis, I., Nikolaou, C., Soursos, P., Koubarakis, M. (2017). Modeling and Querying Greek Legislation Using Semantic Web Technologies. In: Blomqvist, E., Maynard, D., Gangemi, A., Hoekstra, R., Hitzler, P., Hartig, O. (eds) The Semantic Web. ESWC 2017. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10249. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58068-5_36

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58068-5_36

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-58067-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-58068-5

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)