Abstract

La Draga is an open-air settlement located on the shoreline of Lake Banyoles in the Northeast of the Iberian Peninsula. To date, two occupation phases have been differentiated, both attributed to the Early Neolithic (5300–4900 cal BC). The proximity of the lake has meant that a large part of the site has been covered by the water table; as a consequence organic materials are well preserved. The preservation of wooden artefacts offers an excellent opportunity to study the techniques and crafts developed in the first Neolithic villages. This chapter presents the wooden tools related to agricultural practices. This assemblage consists of 45 pointed sticks, 24 of which can be interpreted as digging sticks according to ethnographic and archaeological parallels and the results of a specific experimental program, and 7 sickle handles, one of which holds a flint blade still inserted in its original position. The information these implements provide for the knowledge of the first agriculture is discussed and compared with data supplied by several archaeobotanical proxies. The two approaches are seen to contribute complementary data allowing a more comprehensive reconstruction of the farming practices of Early Neolithic communities in the Western Mediterranean.

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Many Neolithic settlements are found in wetland locations, on the shores of lakes, lagoons or marshes but close to agricultural land. This pattern was recurrent at Early Neolithic sites in Southern Europe (Guilaine et al. 1984; Fugazzola et al. 1993; Rojo et al. 2008; Karkanas et al. 2011). In some cases, proximity to those wet environments has contributed to the preservation of artefacts made of wood and other organic materials, as occurred at the site of La Draga, on the shoreline of Lake Banyoles (northeastern Iberia), but also at sites in other parts of Europe. The chief examples are the Neolithic sites on lakes in the Alps and Jura Mountains, although the oldest settlements known there date from the mid-fifth to the mid-fourth millennium cal BC (Pétrequin and Pétrequin 1988).

However no site enjoys the conditions found at La Draga; its chronology (5320–4980 cal BC, several centuries older than the Alpine sites) and the diversity of wooden elements and artefacts recovered there confer on this site a special status in understanding the strategies carried out in the exploitation of forest resources, technological carpentry skills and use of wooden implements in the daily subsistence activities of the first farming societies in the Western Mediterranean.

1 The Archaeological Site of La Draga

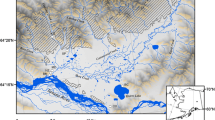

La Draga site has provided evidence of some of the earliest farming societies in open-air settlements in Northeastern Iberia, dated to the late sixth millennium cal BC (Bosch et al. 2011, 2012; Palomo et al. 2014). The site is on the eastern shore of Lake Banyoles , at 173 m asl, 35 km from the Mediterranean Sea and 50 km south of the Pyrenees (Fig. 8.1).

Following its discovery in 1990, excavation has been undertaken at this site during multiple field seasons from 1991 to the present. The first work, initiated under the coordination of the Archaeological Museum of Banyoles, was halted in 2005 in order to finalise the scientific study of its results (Bosch et al. 2000, 2006, 2011, 2012; Tarrús 2008). The project was then redesigned and new institutions were incorporated, such as the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) , the Archaeological Museum of Catalonia (MAC) and the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC-IMF) . During 2008 and 2009 archaeological surveying was carried out on the lake shores—both on land and under water—in order to locate new evidence of settlement and human activity in relation with the prehistoric societies (Bosch et al. 2010; Terradas et al. 2013; Revelles et al. 2014). Finally, from 2010 to the present time, new fieldwork is being conducted in the site (Palomo et al. 2014).

Despite occupying an area of over 8000 m2 (Bosch et al. 2000), archaeological fieldwork to date has concentrated on an area of circa 3000 m2, 825 m2 of which have been excavated in the northern part of the settlement where the site is best preserved. From 1991 to 2005, the excavations concentrated on sectors A, B and C (Fig. 8.2). In Sector A, remains of Neolithic settlement are above the water table and hence waterlogged conditions have not been maintained until the present. However, in Sector B the archaeological evidence is covered by the groundwater level and Sector C is fully under water. New excavations from 2010 have focused on Sectors A and D, the latter located to the south of Sector B and with similar preservation conditions.

Two different phases of occupation with distinctive construction traditions have been documented, both situated by pottery styles within the late Cardial Ware Neolithic culture, in the late sixth millennium and early fifth millennium cal BC according to the available radiocarbon dates. Phase I (5320–4980 cal BC) is characterised by the building of wooden structures (presumably dwellings), attested by the hundreds of stakes, poles and planks that have been recovered from the collapse of these constructions. During this phase the village was a pile dwelling site and the preservation of wooden elements has been possible due to anoxic conditions favoured by the silting of the collapsed structures and the rise in the water table since Neolithic times. Besides uncharred timber remains (Bosch et al. 2006; O. López ongoing PhD), the archaeobotanical record consists of other evidence, both charred and uncharred: charcoal (Piqué 2000; Caruso-Fermé and Piqué 2014), seed and fruit remains (Buxó et al. 2000; Antolín and Buxó 2011; Antolín 2013; Antolín et al. 2014; Antolín and Jacomet 2015), plant tissues and fibres (Bosch et al. 2006), pollen (Revelles et al. 2014), etc. All these forms of evidence constitute an extraordinary palaeoecological record for the region, deserving specific strategies for its sampling, recovery and preservation (Antolín et al. 2013; Piqué et al. 2013).

Phase II (5210–4800 cal BC) is represented by large surfaces covered by pavements of travertine slabs on which domestic activities were carried out. This archaeological level had less optimal conditions of preservation and the organic material is mainly found in a charred state, although some hard-coated uncharred material is occasionally found (Bosch et al. 2000, 2011; Antolín 2013; Palomo et al. 2014).

2 Landscape and Wood Resource Exploitation

Palynological data from La Draga show that the area was densely forested with broadleaf deciduous trees (Quercus, Corylus avellana), conifers (Abies alba, Pinus sp.) and riparian trees (Salix, Fraxinus, Ulmus). Several pollen analyses in the surroundings of Lake Banyoles and the archaeological site show an abrupt decline in oak forest cover coinciding with the Early Neolithic settlement of La Draga (Pérez-Obiol 1994; Burjachs 2000; Revelles et al. 2014).

Charcoal analyses carried out at the archaeological site allowed identifying 18 tree and shrub taxa (Caruso-Fermé and Piqué 2014). Taxa from deciduous forests were the best represented in both occupation phases. Quercus sp. deciduous was the most important taxa. Shrubs were only represented in very small percentages, although their importance increases in the most recent phase, with the dominant taxa being boxwood (Buxus sempervirens) and Rosaceae/Maloideae. Other taxa represented were Acer sp. and conifers including yew (Taxus baccata), pine (Pinus sylvestris-nigra) and juniper (Juniperus sp.). The best represented species from the riparian vegetation was laurel (Laurus nobilis). Other riparian taxa represented were elm (Ulmus sp.), ash (Fraxinus sp.), hazel (Corylus avellana), willow (Salix sp.), alder (Alnus glutinosa), elder tree (Sambucus sp.), poplar (Populus sp.), old man’s beard (Clematis vitalba) and dogwood (Cornus sanguinea). Some of these species might also have grown in the deciduous forest. Finally, some evidence of Mediterranean vegetation was found: holm oak (Quercus ilex–coccifera) and strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo) were identified albeit in smaller proportions.

The study of timber also shows the importance of the exploitation of deciduous forest by the inhabitants of La Draga. Quercus is the dominant taxon in the record (around 95% of remains), and was mainly used to make posts and boards for architectural purposes (Caruso-Fermé and Piqué 2014). Deciduous Quercus sp. and Buxus sempervirens are the most frequently used raw materials in the manufacture of wooden tools recovered in Phase I (Bosch et al. 2006; Palomo et al. 2013), both being used to make a variety of tools. Other taxa collected in the deciduous oak forests were used more sporadically to make certain artefacts, such as maple (Acer sp.), Rosaceae/Maloideae and lime (Tilia sp.). Riparian forests were also exploited to obtain wood including dogwood Cornus sp., Corylus avellana, Laurus nobilis, Populus sp., Salix sp. and Sambucus sp. Three types of conifers, Taxus baccata, Pinus sp. and Juniperus sp., and some typically Mediterranean taxa, Arbutus unedo and Quercus sp. sclerophyllous, were also used to manufacture wooden tools .

3 Neolithic Wooden Artefacts from La Draga

The waterlogged context of Phase I implies excellent preservation of the bioarchaeological record, resulting in one of the richest Early Neolithic assemblages. So far there are over 5,000 wooden remains recovered at La Draga, 2,085 of which show signs of having been transformed by human activity. The largest part of this assemblage correspond to posts attributed to the foundations of dwellings, as well as other posts, poles and planks related with the collapse of walls, roofs or other architectural elements. In addition, 177 wooden utensils and tools of many different kinds have been recovered (Fig. 8.3). According to the functional hypotheses arising from ethnographic analogies and archaeological analyses, they can be related to the following uses (Bosch et al. 2006; Palomo et al. 2011a, 2013; Piqué et al. 2015; de Diego et al. in press):

-

Agricultural instruments: represented by 8 harvesting tools and 45 pointed sticks. According to ethnographic and archaeological parallels, as well as the results of our experimental program, we can argue that most of the former were sickle hafts and most of the latter were digging sticks.

-

Hunting tools: represented by three bows (two fragmented and one whole), some fragments of possible arrow shafts and projectile points.

-

Food processing: a mixer, ladles and containers of various shapes and sizes have been recovered in the category related to food processing.

-

Woodworking: represented by ten adze handles, very similar in shape. Together with them are some pieces of wood which have been interpreted as possible wedges.

-

Textile production: the three combs recovered and some spindle-like needles may have been used for weaving and spinning within textile production, although other functions cannot be excluded.

-

Indeterminate: for many wooden objects it is not possible to suggest a functional hypothesis due to the absence of archaeological or ethnographic parallels, or because they could be multifunctional. Among these are a paddle, some hook-shaped objects, long pointed sticks, etc .

The use of woody raw materials shows a good understanding of their properties by the inhabitants of La Draga (Bosch et al. 2006; Palomo et al. 2013), demonstrating a clear preference for hardwoods like oak and boxwood. The former were used primarily as a building material, almost all posts and poles belong to this taxon, but it was also used to make containers, adze handles and shovels. Boxwood was preferred for making sickle hafts and digging sticks, but also was used to make wedges, needles and combs, among other objects. Some types of objects were made exclusively with one type of wood, such as bows which are all made of yew, shafts of willow, combs of boxwood, containers and shovels of oak.

In accordance with the topic of this chapter we only focus here on the tools used in agricultural activities (digging sticks and harvesting tools). However, a full description of tools and utensils made with organic materials can be found in a monographic publication (Bosch et al. 2006).

4 Pointed Sticks Used as Digging Sticks

Pointed and double-pointed sticks are the most abundant wooden tools in La Draga, where 45 items have been recovered so far (Palomo et al. 2013). These instruments are made entirely of wood, so in normal conditions they would be completely invisible in the archaeological record.

Archaeological wooden objects present difficulties when studied with the usual techniques of use-wear analysis. The archaeological artefacts from waterlogged deposits are usually saturated in water when recovered, so the reflection of light on shiny surfaces does not permit a reliable reading and interpretation of the traces. Moreover, once restored, the surfaces tend to be deformed, and some use and technological traces may be altered. In order to solve this circumstance, a structured-light 3D scanner has been used to measure the three-dimensional shape by means of projected light patterns. The equipment used (CSIC-IMF, Barcelona) allows very high precision resolution (0.015 mm) in a great variety of scientific metrology applications. Likewise, the 3D models allow good reproduction and modelling of both the archaeological and the experimental objects, thus enabling the study of use-wear as well as providing a tool with which to register the original modifications due to prehistoric manufacture and use before their deformation by restoration in archaeological laboratories (Fig. 8.4) (Palomo et al. 2013; Piqué et al. 2013). Despite the fragility of archaeological wooden artefacts, their systematic study by means of a 3D scan before restoration allows their surfaces to be recorded with greater precision. This line of research will surely open new ways to approach the understanding of prehistoric tools as well as new pedagogical possibilities in the dissemination of results obtained by archaeological research .

The pointed sticks recovered in La Draga are made in a wide variety of sizes and raw materials, and their length usually fluctuates between 70 and 80 cm, although the longest can reach 130 cm (Bosch et al. 2006). According to this variability, they would probably have had different functions. In some cases these are branches that have been shaped into a sharp end by means of an adze, as can be recognized from the traces that this stone tool has left over the wood surface. However, the uniformity and standardisation of the double-pointed sticks are noteworthy. These are all made from boxwood (Buxus sempervirens) with both ends generally finishing in a point, when they are made from an entire branch, or a pointed end and a bevelled edge with convex delineation at the opposite end, when a longitudinal segment of a boxwood branch is used (Fig. 8.5).

Double-pointed sticks made from a stem segment display facets, removals and various types of traces, some related to processes involved in their production (tool marks such as splitting, adze removals, scratches and sanding marks) and others generated as a result of their use (use-wear like fractures, flattened areas, use-polishes, abrasion and scratches) (Fig. 8.6). Experimental studies have shown that it is possible to discriminate one type of trace from the other, which has allowed confirmation of their use as digging sticks (López et al. 2012). The facets associated with production processes are of different types. Facets produced using wooden wedges to split the stem are long and may have the same length as the stick, while the removals resulting from adze work are short and narrow. Both are visible on the archaeological digging sticks, which also have polished ends.

To determine the function of these instruments has been another of the objective of the study. At first glance, based on ethnographic parallels, it was thought that they were digging sticks, related with the agricultural task of turning the soil over before sowing. Based on this hypothesis, the sticks produced experimentally were used for this task. This not only aimed to ascertain the efficiency of the tools in this specific activity, but also to obtain a complete record of the use-wear resulting from this action on the active parts of the tool. The main activity was driving the end of the stick into the soil and levering it up (Fig. 8.7). The experimental use of digging sticks to turn the soil produced several macroscopic traces: striations, microscars, notches, fragmentation and flattening of the fibres and polishing. It proved possible to characterise them and differentiate them from one another (López et al. 2012). These types of use-wear were also observed in the surfaces and edges of most of the archaeological sticks. In this way, at least 24 items of the 45 pointed sticks are thought to have been used as digging sticks. According to the length of the sticks and the absence of criteria suggesting that these tools were hafted, they would have been used with both hands, in a kneeling position. Their efficacy is restricted to turning the top centimetres of the soil surface, as they do not allow deep rotation of the land.

5 Wooden Tools Used in Harvesting Tasks

These tools have already been the subject of a specific publication (Palomo et al. 2011a), and therefore only their more relevant aspects will be mentioned here. More specific details on the tools themselves can also be found in the monograph on the wooden tools from La Draga (Bosch et al. 2006). The harvesting tools found in the oldest occupation in La Draga (Phase I) consist of a wooden blade probably used to reap reeds or other aquatic plants and seven sickle handles. Only in one case has a flint blade been found still inserted in the slot in the handle.

The wooden blade is made from deciduous oak (Quercus sp.) and consists of a cylindrical haft, finished with a spherical knob at the proximal end and an active part at the opposite end (Fig. 8.8). The active part is a rectangular appendage with a concave cutting edge. This bore several marks that would suggest that it was used to pull up non-woody plant fibre, such as cereals or aquatic plants. At La Draga, not only numerous seeds from different species of domestic and wild plants have been found, but also some basketwork containers made with plant fibres from reeds and other aquatic plants. Thus tools like this one could be used as a reaper, to pull up stems of these plants in order to take advantage of their length for basket making .

The sickle handles were made from juniper wood (Juniperus sp.) in one case, elder tree (Sambucus sp.) in another and boxwood (Buxus sempervirens) in the remaining five. All these types of wood are hard and resilient. The hafts have the same general morphology; they display a rectilinear shaft, where a slot has been made and into which a blade of flint would be inserted mostly in an oblique way. A lateral appendix serves to gather plant stems as part of the harvesting motion (Fig. 8.9). In most cases there is only one slot per shaft, although in one example there are two slots in the same shaft. Despite them not all being whole (only five, plus one fragmented and another shaft fragment with the slot), it is obvious that in all cases the morphology takes advantage of the shape of the branches in the wild, either because the branch was already angle shaped or because it had a secondary branch (Palomo et al. 2013). The dimensions are variable (Table 8.1); the handle made from juniper wood is the largest but it is fragmented and its full length cannot be appreciated.

Some traces preserved on the surfaces of the sickle hafts allow a determination of the steps followed in the manufacturing process, even if it is quite variable. Once the blank had been chosen, the shaft and the appendix were generally thinned longitudinally with an adze around their whole perimeter. When the desired length was achieved the shaft was thinned more intensively until it was enough fine to be broken. This type of cutting has been attested for at least two sickle handles as well as for other wooden objects. Furthermore, there are two sickle haft blanks with removals left by an adze-like tool. As regards their finishing, on the one hand, most handles made from boxwood are well polished over their entire surface. On the other hand, the sickle haft made from elder tree wood is the least worked and still preserves the original shape of the branch. In some cases, at the proximal end of the shaft, a knob has been carved so that the sickle could be held more easily.

The form and function of the sickles can be best appreciated in the case of the one made from elder tree wood, which retained its flint blade in place (Fig. 8.10). It consists of a cylindrical haft terminating in a cylindrical knob at the proximal end, with a branch forming a right angle at the distal end. The flint blade was fixed in a groove on the axis of the shaft, obliquely in relation to the handle. According to the phytolith study carried out (Juan 2000), the flint blade was affixed with pine resin (Pinus sylvestris). Use-wear analysis of the blade has confirmed its use as a sickle (Palomo et al. 2011a). Very shiny micro-polish was observed, spreading substantially towards the inner area, characteristic of cereal cutting. In the inner part of the micro-polish area, some deep narrow striations both parallel and diagonal to the edge indicate the sickle kinematics in harvesting activities. According to its morphology, motion dynamics and use-wear observed on the flint blade, the sickle would have been used for cutting the higher part of the stem—ear included—rather than the whole stalk. Indeed, the lateral appendix used to gather plant stems during the harvesting motion would impede a cut close to soil level in order to obtain the ear and most of the stalk (Fig. 8.11). Furthermore, the blade displays no evidence of abrasive soil particles, as specified below .

6 Harvesting Activities Through Flint Blades

Use-wear analysis carried out with the stone tools recovered in La Draga has shown that some flint blades were used as sickle blades in harvesting activities (Gibaja 2011). The knapped stone tool assemblage from La Draga consists of circa 1000 items. Most of them (93%) have been knapped in micro-cryptocrystalline flint coming from formations of Oligocene-Miocene age in the Narbonne-Sigean Basin, 110 km north of Banyoles (Terradas et al. 2012). Despite some evidence attesting the development of flint knapping processes in La Draga, the remains characteristic of core shaping-out are found in very small proportions. Therefore, flint products would have been introduced in La Draga largely as cores already shaped out or as blade products already knapped. The most common implemented knapping technique would be indirect percussion, allowing the production of blades that rarely exceed 5–6 cm in length (Palomo et al. 2011b).

A large number of used tools (about 24.6%) were used on non-woody vegetable matter such as cereals. Most of these products are blades of which a large proportion (60%) was used on both their edges, so the cutting edges of the blades would be interchangeable whenever they became unusable. The rest of the tools are flakes, with only one edge used. The characteristics of use-wear on several of these blades, particularly the micro-polishes, are probably connected with cereal reaping. In some cases, due to the presence of specific micro-polishes, it can be proposed that the sickles were used for cutting unripe cereals for limited time periods or even for cutting other kinds of wild plants such as reeds (Gibaja 2011).

Some blades present very extensive micro-polish with many striations produced by a totally rounded edge. Their comparison with similar results obtained from experimentation has revealed that these kinds of use-wear might have developed as a consequence of continuous contact with the ground, during low reaping, cutting the stalk in its lower part or due to the cutting of the culms on the ground (Clemente and Gibaja 1998). According to the distribution of micro-polishes along the flint blade edge, if these blades were hafted they would be parallel to the axis of the sickle handle. Although this type of sickle is well represented by means of the flint blades, as yet in La Draga no wooden haft that could be attributed to this type of sickle has been recovered .

Therefore two types of sickles are attested in La Draga. On the one hand, sickles with a lateral appendix and a single flint blade are inserted obliquely to the shaft. On the other hand, sickles with one or several flint blades are inserted parallel to the shaft. This difference could be related to diverse technical traditions noted in sickle handling in the Western Mediterranean (Ibáñez et al. 2008; Ibáñez et al. 2017). These authors differentiate between straight or curved sickles with short blades inserted diagonally in order to shape a toothed edge (South Portugal, Andalusia and the Spanish Levantine coast), sickles with one or more blades inserted parallel to the handle (Provence and Languedoc, Catalonia, as attested in La Draga by means of the use-wear analysis of flint blades) and places where harvesting activities were carried out without sickles (Cantabrian Spain). These technical traditions seem to be already present in the earliest Neolithic communities settled in these areas, and stay unchanged for over a millennium.

A specific type of sickle with a single blade inserted obliquely to the shaft is well documented in La Draga by the examples of wooden handles (Figs. 8.9 and 8.10). This type of sickle would also be present at other Early Neolithic sites in inland Iberia such as Revilla del Campo and La Lámpara (Ambrona, Soria) (Gibaja 2008), and the mining complex of Casa Montero (Terradas et al. 2011).

7 The Archaeobotanical Data: Crops

The carpological record—seed and fruit remains—recovered in the two occupation phases documented at La Draga is very abundant. This chapter focuses on the results obtained for Phase I that provided the wooden tools, and specifically on Sector D, where this phase was clearly identified and proper sampling and sieving techniques were applied (Antolín 2013; Antolín et al. 2013). Samples from three profile columns (circa 5 L of volume of sediment), around 40 surface samples (circa 30 L of sediment) and several bulk samples were studied in the context of a PhD (Antolín 2013). A previous publication focuses specifically on the charred record from this occupation phase (Antolín et al. 2014).

Several potential crops were identified in both charred and waterlogged states in Phase I (Fig. 8.12): hulled barley (mostly) of two-rowed type (Hordeum distichum); naked wheat, mainly of tetraploid type but also of hexaploid type (Triticum durum/turgidum; Triticum aestivum); emmer (Triticum dicoccum); einkorn (Triticum monococcum); the so-called new glume wheat (Triticum sp./new type); and opium poppy (Papaver somniferum). The representation of each crop differs depending on the preservation type .

Both grains and chaff remains of barley were significantly better represented in the charred record. In fact, several ear fragments of two-rowed barley were found in charred state in an area where large concentrations of charred grain and chaff were found (probably an in situ-burnt store), which was interpreted as a clear sign that they were stored in ear form. Nevertheless, in comparison with naked wheat, it seems to be a secondary crop. Uncharred chaff remains of barley were found but only in small numbers. This probably confirms the lesser importance of the taxon at the site.

Naked wheat is the best represented cereal at La Draga, both in the charred and in the waterlogged record. It was present in almost 90% of the samples from Phase I and high concentrations of remains were found in particular areas, showing that stores could have been burnt in situ. It is also the best represented crop in other areas and phases within the settlement (Buxó et al. 2000; Antolín and Buxó 2011). Charred chaff remains of naked wheat were also abundant. Grain was probably stored after manual threshing and almost clean of any weeds (Antolín et al. 2014). The representation of charred remains of glume wheat was rather limited, but einkorn was almost as well represented as naked wheat in the waterlogged record. It is therefore difficult to say if they were minor crops or unwanted contaminants in the fields. No concentrations of any of them were found.

Opium poppy is well attested among the waterlogged remains, being represented in all of the systematic surface samples. Charred remains were very scarce in both levels. The find of a charred capsule fragment could respond to the processing of capsules in the house in order to obtain the grains. The capsule fragments would then be discarded and by chance they might become charred. This is a very rare case, even for a lakeshore site where the preservation of charred remains is better than in dry sites. The different ways in which poppy could have been used at La Draga are, at the moment, unknown. Some of the closest references were found in the La Marmotta site, another Early Neolithic lakeshore settlement near Rome, where the appearance of opium poppy was reported (Rottoli 1993). Apparently, some of these remains could have appeared within a particular ritual context (Merlin 2003). The contexts in which it has appeared so far in La Draga are of domestic type, and they would rather suggest a more regular consumption of the plant. On the other hand, there are no reasons to exclude the possibility that the psychoactive properties of the plant were known and used. No cultivated legumes have as yet been identified in this phase of occupation at La Draga.

Potential weeds are most easily identified in the charred record, due to the more complex routes of entry that affect the waterlogged record. They appeared in low numbers and were mostly annuals (Avena sp., Bromus sp., Lathyrus aphaca type, Vicia sepium, V. villosa type). Most of them were classified as ‘big-free-heavy’, according to the classification of G. Jones (1984), which is typical for cleaned crops. Particularly noteworthy was the relatively large number of legumes within this group of plants. These may be classified as climbing taxa, that is to say, plants which climb on other plants and so are difficult to detach as weeds. No plants of low height were identified. This type of weeds would be a hint towards a high harvesting technique (for a more detailed discussion on this topic see Antolín et al. 2014). This would be in accordance to the type of sickles found at the site .

8 Discussion

The analysis of use-wear preserved on tool surfaces and the experimentation carried out on the hypotheses of tool use, in connection with the archaeobotanical data, enable a discussion on the techniques of cultivation and harvesting. In addition, archaeobotanical and geoarchaeological proxies provide helpful evidence to evaluate the impact of these activities on the landscape.

The assemblage of wooden tools used in agricultural practices is quite restricted, being limited to digging sticks and harvesting tools—essentially sickles. Pointed sticks used as digging sticks in La Draga could be used for turning over the soil to improve its oxygenation. Use-wear recorded on their edges and surfaces is similar to that produced during the experimental studies, attesting their use in actions where reiterated contact with abrasive particles—such as these located into the soil—would have occurred. Nevertheless the morphology and size of the digging sticks prevent deep penetration when they are manually stuck into the ground. So, their efficiency is limited to the uppermost layers of the soil, preventing a deep rotation. We cannot exclude the possibility that they were anyway used for this purpose, but alternative interpretations are possible when taking into consideration other proxies.

The use-wear evidence on flint blades used for harvesting activities seems to confirm the presence of two types of sickles , each related with respective harvesting motions and technical traditions attested among the earliest farming communities in the Western Mediterranean. On the one hand, sickles with one or several flint blades were hafted parallel to the axis of the shaft and used in a low harvesting technique, that is to say cutting the stalk by its lower part. This type of sickle would not be represented among the wooden hafts from La Draga. On the other hand, sickles with a single flint blade are inserted obliquely in the sickle shaft. This type of sickle is well attested among the wooden handles, in which a lateral appendix has been shaped out in order to gather plant stems during the harvesting motion. In this case, the sickle would be used for cutting the higher part of the stem—ear included—rather than the whole stalk.

Some experimental studies concluded that sickles with lateral appendix would only be necessary when the plants were not densely sown (Pétrequin et al. 2006). Therefore it is possible that cereals were sown in rows by dibbling with digging sticks such as those recovered in La Draga. The type of potential weeds (climbing taxa, lacking low-growing taxa) identified at the site would also indicate a high harvesting technique (Antolín et al. 2014). Furthermore, the finding of clean grain stores almost lacking weeds would suggest very intensively weeded fields, which would support a medium- to low-density sowing technique. In conclusion, the available data seem to support high harvesting of the crop, between the ear and the first culm node. This would agree with the existence of medium- to low-densely sown fields and the use of the sickle types that were found at La Draga. Similar conclusions were achieved in previous work carried out in the Lake Constance region, at the northern foot of the Alps (Schlichtherle 1992).

Cereals are the most important crop in the site. Among them, the importance of naked wheat from a quantitative point of view should be noted. The fact that the identified weed taxa were mostly annuals would indicate that the cultivation of the fields was permanent, while the presence of plants with vegetative reproduction (like Vicia sepium) could indicate intensive soil perturbation. The available archaeobotanical record lacks evidence in favour of shifting agriculture (Bogaard 2002; Antolín 2013; Antolín et al. 2014; Revelles et al. 2014).

In that sense, the opening of farming plots, which were probably small and intensively managed, had a relatively minor impact on the landscape (Antolín et al. 2014). This might enter into some contradiction with some of the palynological data available. New archaeobotanical and geoarchaeological proxies obtained from core sampling carried out on the western shore of Lake Banyoles show how deforestation processes affected natural vegetation development in the Early and Late Neolithic, in the context of broadleaf deciduous forest resilience against cooling and drying oscillations (Revelles et al. 2014, 2015). The first agriculture in the area took place in a densely forested landscape, where riparian and deciduous forests covered the surroundings of the settlement, as shown by pollen and charcoal analyses. The effects of later maintenance of the clearances opened in oak forests should also be taken into account, either for the specific activities related to strategies involved in the management of plant resources or by means of the productive processes implied in an intensive farming system. The intensive exploitation of oak forest to obtain raw materials for the construction of dwellings would be mainly responsible for the large impact on vegetation dynamics at the beginning of the Neolithic occupation at La Draga. Probably, the perpetuation of these clearances was the main anthropogenic impact on the environment during the Neolithic (Revelles et al. 2014, 2015).

References

Antolín, F. (2013). Of cereals, poppy, acorns and hazelnuts. Plant economy among early farmers (5400–2300 cal BC) in the NE of the Iberian Peninsula. An archaeobotanical approach. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10803/128997.

Antolín, F., & Buxó, R. (2011). L’explotació de les plantes: contribución a la història de l’agricultura i de l’alimentació vegetal del Neolític a Catalunya. In A. Bosch, J. Chinchilla, & J. Tarrús (Eds.), El poblat lacustre del Neolític antic de la Draga. Excavacions 2000–2005, Monografies del CASC (Vol. 9, pp. 147–174). Girona: CASC—Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya.

Antolín, F., & Jacomet, S. (2015). Wild fruit use among early farmers in the Neolithic (5400–2300 cal BC) in the north-east of the Iberian Peninsula: An intensive practice? Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 24(1), 19–33.

Antolín, F., Blanco, A., Buxó, R., Caruso, L., Jacomet, S., López, O., et al. (2013). The application of systematic sampling strategies for bioarchaeological studies in the Early Neolithic Lakeshore site of La Draga (Banyoles, Spain). Journal of Wetland Archaeology, 13(1), 29–49.

Antolín, F., Buxó, R., Jacomet, S., Navarrete, V., & Saña, M. (2014). An integrated perspective on farming in the early Neolithic lakeshore site of La Draga (Banyoles, Spain). Environmental Archaeology, 19(3), 241–255.

Bogaard, A. (2002). Questioning the relevance of shifting cultivation to Neolithic farming in the loess belt of Europe: evidence from the Hambach Forest experiment. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 11, 155–168.

Bosch, A., Buxó, R., Chinchilla, J., Nieto, X., Palomo, A., Piqué, R., et al. (2010). Prospecció arqueològica de la riba de l’Estany de Banyoles 2008–2009. In S. Manzano, A. Martín, M. Mataró, & J. M. Nolla (Eds.), Desenes Jornades d’Arqueologia de les Comarques de Girona (pp. 745–751). Arbúcies: Museu Etnològic del Montseny—La Gabella.

Bosch, A., Buxó, R., Chinchilla, J., Palomo, A., Piqué, R., Saña, M., et al. (2012). El jaciment neolític lacustre de la Draga, Quaderns de Banyoles (Vol. 13). Banyoles: Ajuntament de Banyoles.

Bosch, A., Chinchilla, J., & Tarrús, J. (Eds.). (2000). El poblat lacustre neolític de la Draga. Excavacions de 1990–1998, Monografies del CASC (Vol. 2). Girona: CASC—Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya.

Bosch, A., Chinchilla, J., & Tarrús, J. (Eds.). (2006). Els objectes de fusta del poblat neolític de la Draga. Excavacions de 1995–2005, Monografies del CASC (Vol. 6). Girona: CASC—Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya.

Bosch, A., Chinchilla, J., & Tarrús, J. (Eds.). (2011). El poblat lacustre del Neolític antic de la Draga. Excavacions 2000–2005, Monografies del CASC (Vol. 9). Girona: CASC—Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya.

Burjachs, F. (2000). El paisatge del neolític antic. Les dades palinològiques. In A. Bosch, J. Chinchilla, & J. Tarrús (Eds.), El poblat lacustre neolític de la Draga. Excavacions de 1990 a 1998, Monografies del CASC (Vol. 2, pp. 46–50). Girona: Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya.

Buxó, R., Rovira, N., & Sauch, C. (2000). Les restes vegetals de llavors i fruits. In A. Bosch, J. Chinchilla, & J. Tarrús (Eds.), El poblat lacustre neolític de la Draga. Excavacions de 1990 a 1998, Monografies del CASC (Vol. 2, pp. 129–140). Girona: Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya.

Caruso-Fermé, L., & Piqué, R. (2014). Landscape and forest exploitation at the ancient Neolithic site of La Draga. The Holocene, 24(3), 266–273.

Clemente, I., & Gibaja, J. F. (1998). Working processes on cereals: an approach through microwear analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science, 25(5), 457–464.

De Diego, M., Piqué, R., Palomo, A., Terradas, X., Clemente, I., & Mozota, M. (in press). Traces of textile technology in the lacustrine Early Neolithic site of La Draga (Banyoles, Catalonia). In Proceedings of the IVth International Conference on Experimental Archaeology. Burgos: Museo de la Evolución Humana.

Fugazzola, M., D’Eugenio, G., & Pessina, A. (1993). La Marmotta. Scavi 1989. Un abitato perilacustre di età neolitica. Bulletino di Paletnologia Italiana, 84, 181–304.

Gibaja, J. F. (2008). La función del utillaje lítico documentado en los yacimientos neolíticos de Revilla del Campo y La Lámpara (Ambrona, Soria). In M. A. Rojo, M. Kunst, R. Garrido, I. Garcia, & G. Moran (Eds.), Paisaje de la memoria: asentamientos del neolítico antiguo en el Valle de Ambrona, Soria, España, Arte y Arqueología (Vol. 23, pp. 451–493). Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid.

Gibaja, J. F. (2011). La función de los instrumentos líticos tallados. In A. Bosch, J. Chinchilla, & J. Tarrús (Eds.), El poblat lacustre del Neolític antic de la Draga. Excavacions 2000–2005, Monografies del CASC (Vol. 9, pp. 91–100). Girona: CASC—Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya.

Guilaine, J., Freises, A., & Montjardin, R. (1984). Leucate-Corrège: Habitat noyé du Néolithique cardial. Toulouse: Centre d’Anthropologie des Sociétés Rurales.

Ibáñez, J. J., Clemente, I., Gassin, B., Gibaja, J. F., González, J. E., Márquez, B., et al. (2008). Harvesting technology during the Neolithic in South-West Europe. In L. Longo & N. Skakun (Eds.), ‘Prehistoric Technology’ 40 years later: Functional studies and the Russian Legacy, British Archaeological Reports—International series (Vol. S1783, pp. 183–196). Oxford: Archaeopress.

Jones, G. (1984). Interpretation of archaeological plant remains: ethnographic models from Greece. In W. Van Zeist & W. A. Casparie (Eds.), Plants and ancient man (pp. 43–61). Rotterdam: Balkema.

Juan, J. (2000). Estudio de los restos de resina asociados a un diente de hoz neolítico de La Draga. In A. Bosch, J. Chinchilla, & J. Tarrús (Eds.), El poblat lacustre neolític de la Draga. Excavacions de 1990–1998, Monografies del CASC (Vol. 2, pp. 149–150). Girona: CASC—Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya.

Karkanas, P., Pavlopoulos, K., Kouli, K., Ntinou, M., Tsartsidou, G., Facorellis, Y., et al. (2011). Palaeoenvironments and site formation processes at the Neolithic lakeside settlement of Dispilio, Kastoria, Northern Greece. Geoarchaeology, 26(1), 83–117.

López, O., Piqué, R., & Palomo, A. (2012). Woodworking technology and functional experimentation in the Neolithic site of La Draga (Banyoles, Spain). In Experimentelle Archäologie in Europa, Bilanz 2012 (pp. 56–65). Schleswig: EXARC Conference 2011.

Merlin, M. D. (2003). Archaeobotanical evidence for the tradition of psychoactive plant use in the old world. Economic Botany, 57, 295–323.

Palomo, A., Camarós, E., & Gibaja, J. F. (2011a). La indústria lítica tallada. Una visió tècnica i experimental. In A. Bosch, J. Chinchilla, & J. Tarrús (Eds.), El poblat lacustre del Neolític antic de la Draga. Excavacions 2000–2005, Monografies del CASC (Vol. 9, pp. 71–89). Girona: CASC—Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya.

Palomo, A., Gibaja, J. F., Piqué, R., Bosch, A., Chinchilla, J., & Tarrús, J. (2011b). Harvesting cereals and other plants in Neolithic Iberia: the assemblage from the lake settlement at La Draga. Antiquity, 85, 759–771.

Palomo, A., Piqué, R., Terradas, X., Bosch, A., Buxó, R., Chinchilla, J., et al. (2014). Prehistoric occupation of Banyoles lakeshore: Results of recent excavations at La Draga site, Girona, Spain. Journal of Wetland Archaeology, 14, 58–73.

Palomo, A., Piqué, R., Terradas, X., López, O., Clemente, I., & Gibaja, J. F. (2013). Woodworking technology in the Early Neolithic site of La Draga (Banyoles, Spain). In P. C. Anderson, C. Cheval, & A. Durand (Eds.), Regards croisés sur les outils liés au travail des végétaux (pp. 383–396). Antibes: Éditions APDCA.

Pérez-Obiol, R. (1994). Análisis polínicos de sedimentos lacustres y de suelos de ocupación de la Draga (Banyoles, Pla de l’ Estany). In I. Mateu-Andrés, M. Dupré-Ollivier, J. Güemes-Heras, & M. E. Burgaz-Moreno (Eds.), Trabajos de Palinología básica y aplicada (pp. 277–284). València: Universitat de València.

Pétrequin, A. M., & Pétrequin, P. (1988). Cités lacustres du Jura. Préhistoire des lacs de Chalain et de Clairvaux (4000–2000 ans av. J.-C.). Paris: Editions Errance.

Pétrequin, P., Lobert, G., Maitre, A., & Monnier, J. (2006). Les outils à moissonner et la question de l’introduction de l’araire dans le Jura (France). In P. Pétrequin, R. Arbogast, A. Pétrequin, S. van Willigen, & M. Bailly (Eds.), Premier chariots, premiers araires. La diffusion de la traction animale en Europe pendant les IVe et IIIe millénaires avant notre ère (pp. 107–120). Paris: CNRS Éditions.

Piqué, R. (2000). El paisatge del Neolític antic: les dades antracològiques. In A. Bosch, J. Chinchilla, & J. Tarrús (Eds.), El poblat lacustre neolític de la Draga. Excavacions de 1990–1998, Monografies del CASC (Vol. 2, pp. 50–53). Girona: CASC—Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya.

Piqué, R., Palomo, A., Terradas, X., Aguer, C., Bogdanovic, I., Chinchilla, J., et al. (2013). Registro, análisis y conservación de los objetos de madera del yacimiento neolítico de La Draga (Banyoles, Catalunya). In X. Nieto, A. Ramírez, & P. Recio (Eds.), I Congreso de Arqueología náutica y subacuática española (pp. 1136–1148). Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte.

Piqué, R., Palomo, A., Terradas, X., Tarrús, J., Buxó, R., Bosch, A., et al. (2015). Characterizing prehistoric archery: Technical and functional analyses of the Neolithic bows from la Draga (NE Iberian Peninsula). Journal of Archaeological Science, 55, 166–173.

Revelles, J., Antolín, F., Berihuete, M., Burjachs, F., Buxó, R., Caruso, L., et al. (2014). Landscape transformation and economic practices among the first farming societies in Lake Banyoles (Girona, Spain). Environmental Archaeology, 19(3), 298–310.

Revelles, J., Cho, S., Iriarte, E., Burjachs, F., van Geel, B., Palomo, A., et al. (2015). Mid-Holocene vegetation history and Neolithic land-use in the Lake Banyoles area (Girona, Spain). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 435, 70–85.

Rojo, M. A., Kunst, M., Garrido, R., Garcia, I., & Moran, G. (Eds.). (2008). Paisaje de la memoria: asentamientos del neolítico antiguo en el Valle de Ambrona, Soria, España, Arte y Arqueología (Vol. 23, p. 4). Valladolid: Universidad de Valladolid.

Rottoli, M. (1993). “La Marmotta”, Anguillara Sabazia (RM). Scavi 1989. Analisi paletnobotaniche: Prime risultanze. Bulletino di Paletnologia Italiana, 84, 305–315.

Schlichtherle, H. (1992). Jungsteinzeitliche Erntegeräte am Bodensee. Plattform, 1, 24–44.

Tarrús, J. (2008). La Draga (Banyoles, Catalonia), an Early Neolithic lakeside village in Mediterranean Europe. Catalan Historical Review, 1, 17–33.

Terradas, X., Antolín, F., Bosch, A., Buxó, R., Chinchilla, J., Clop, X., et al. (2012). Áreas de aprovisionamiento, territorios de subsistencia y producciones técnicas en el Neolítico antiguo de La Draga. In M. Borrell, F. Borrell, J. Bosch, X. Clop, & M. Molist (Eds.), Networks in the Neolithic. Exchange of raw materials, products and ideas in the Western Mediterranean (VII–III millennium BC), Rubricatum (Vol. 5, pp. 441–448). Gavà: Museum of Gavà.

Terradas, X., Clemente, I., & Gibaja, J. F. (2011). Mining tools use in a mining context or how can the expected become unexpected. In M. Capote, S. Consuegra, P. Díaz-del-Río, & X. Terradas (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference of the UISPP Commission on Flint Mining in Pre- and Protohistoric Times, British Archaeological Reports—International series (Vol. S2260, pp. 243–252). Oxford: Archaeopress.

Terradas, X., Palomo, A., Piqué, R., Buxó, R., Bosch, A., Chinchilla, J., Tarrús, J., & Saña, M. (2013). El poblamiento del entorno lacustre de Banyoles: aportaciones de las prospecciones subacuáticas. In X. Nieto, A. Ramírez, & P. Recio (Eds.), I Congreso de Arqueología náutica y subacuática española (pp. 709–719). Madrid: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte.

Acknowledgments

This research was undertaken through the following projects ‘Organización social de las primeras comunidades agrícola-ganaderas a partir del espacio doméstico: Elementos estructurales y áreas de producción y consumo de bienes’ (HAR2012-38838-C02-01), and ‘Arquitectura en madera y áreas de procesado y consumo de alimentos’ (HAR2012-38838-C02-02), funded by the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad—Subdirección General de Proyectos de Investigación (Spain), and ‘La Draga en el procés de neolitització del Nordest peninsular; 2014–2017’ funded by the Generalitat de Catalunya. The research has been conducted in the framework of the research group AGREST (2014 SGR 1169) supported by the Generalitat de Catalunya.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Terradas, X. et al. (2017). Farming Practices in the Early Neolithic According to Agricultural Tools: Evidence from La Draga Site (Northeastern Iberia). In: García-Puchol, O., Salazar-García, D. (eds) Times of Neolithic Transition along the Western Mediterranean. Fundamental Issues in Archaeology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52939-4_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52939-4_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-52937-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-52939-4

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)