Abstract

In this chapter it is argued that topicalization and focalization such as heavy XP shift involve satisfying the same feature, named [S(yntactic)-Focus], which is satisfied in a left or right peripheral position, and that whether the resulting chain functions as topic or focus is determined representationally at the LF interface. It is demonstrated that these types of movement are subject to the mechanism of minimal Search and MCL applied to Float. Further, based upon the observation that topicalization and wh-movement undergo Float in the same fashion and that wh-movement may block an application of topicalization and vice versa, I argue that this operation also involves satisfaction of [S-Focus]. It is finally argued that this analysis of topicalization and focus movement in terms of satisfying [S-Focus] features is naturally extended to capture the locality effects observed in such elliptic constructions as gapping . Under the assumption that the remnant phrases in the second conjunct carry [S-Focus] features and (ii) that satisfaction of this feature involves the mechanism of minimal Search and Float, it is demonstrated that the second remnant in the second conjunct undergoes rightward movement.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

Nor does this imply that all phrases that are interpreted as foci must carry this feature. Thus such phrases may simply be pronounced with heavy stress without being shifted. In this sense, the feature [S-Focus] is only one way in which a phrase can be interpreted as focus. As the editors correctly point out, a feature named [α] will do instead of [S-Focus] as long as this feature is taken to be licensed in a peripheral position and it is responsible for both topicalization and heavy NP shift (and wh-movement as well, as argued in Sect. 6.3). Nonetheless, I use [S-Focus] in the text to give the reader some grasp of what syntactic and semantic roles its carrier will play in the computational as well as the interpretive component.

- 2.

Thus, I assume throughout this chapter that the linear order information is available not only to the PF component but also to the LF component.

- 3.

This operation of assignment of [S-Focus] needs to obey cyclicity just like other syntactic operations. Otherwise, we could not prevent such assignment from taking place after another instance of movement for licensing [S-Focus], so that this incorrectly allows a violation of minimality with respect to focus movement.

- 4.

I assume that the linear order algorithm that incorporates (7) is applied within narrow syntax, so that the linear order information can be available to the LF component as well. See Footnote 2 for a relevant remark.

- 5.

One may raise the question whether subject, when inserted into Spec-vP, can satisfy its [S-Focus] in this position. Though I do not have any decisive evidence to answer this question, I assume throughout this chapter that a phrase bearing [S-Focus] must create an operator-variable chain. Hence, subject must satisfy its [S-Focus] in a position other than its base-generated Spec-vP.

- 6.

Saito and Fukui (1998) argue that English heavy NP shift shares its basic properties with scrambling. One piece of evidence they provide for this claim is that multiple heavy XP shift, such as illustrated in (19), is in fact possible. They give the following example:

(i) John told t i t j yesterday [a most incredible story]i [to practically everyone who was willing to listen]j. (Saito and Fukui 1998: 445)

I have no idea about what is going on here. This might suggest that there are some dialectal or idiolectal variations among native speakers. I must leave further investigation on this point for future research.

- 7.

I claim in Sect. 6.4 that the DO the house that he will live in is closer to vP than the PP with a hammer under the assumption that what precedes is structurally higher than what follows in VP structures.

- 8.

We have been assuming that Spec-vP also serves as a possible landing site for satisfying [S-Focus], though such a way of licensing [S-Focus] always ends up receiving no appropriate LF interpretation at least in English. Given this assumption, Spec-CP cannot act properly as an escape hatch for long-distance topicalization. I can think of two ways to get over this problem. One is to stipulate that Spec-vP is not a peripheral position, hence does not serve as a possible landing site for satisfying [S-Focus]. This has some intuitive appeal in that Spec-vP does not seem to be peripheral, because of the existence of subject in Spec-TP. The other way is to modify the extension of a minimal domain via a head chain in such a way that a minimal domain of a head is extended up to a domain into which the head moves up. Given the assumption that head movement takes place from V to C sequentially, it follows that these projections work as if they constitute one minimal domain within which any two positions count as equidistant from any arbitrary position below. Alternatively, we may rely on the notion of extended projections in the sense of Grimshaw (2001) to define equidistantce, so that the minimal domain of α relevant for (31) is defined as the maximal extended projection immediately dominating α. Given that C, T, and v categories are extended projections of V, we can maintain that all positions contained in one series of C-T-v-V extended projections are equidistant from some lower position. See the next section for the claim that [S-Focus] can be licensed in Spec-vP in pseudogapping constructions, which is compatible only with the second option mentioned above.

- 9.

Much the same mechanism carries over to cases of successive-cyclic A-movement such as (i), which has the derivation indicated in (ib).

In this derivation, John must go through the embedded Spec-TP to satisfy MCL, since even though the Case-feature of John is not actually licensed in this position, it counts as a possible landing site for floating John, given the assumption that any type of Spec-TP serves as such, irrespective of the inherent property of T.

In this derivation, John must go through the embedded Spec-TP to satisfy MCL, since even though the Case-feature of John is not actually licensed in this position, it counts as a possible landing site for floating John, given the assumption that any type of Spec-TP serves as such, irrespective of the inherent property of T. - 10.

I will argue in this section that a wh-phrase that will undergo overt movement to Spec-CP is assigned a [S-Focus] feature, so that Spec-CP is an actual position for licensing a [S-Focus] feature as long as its bearer also serves to mark a clausal type of this CP. On the other hand, CP-adjoined positions never serve to satisfy a [S-Focus] feature or serve for an escape hatch. This indicates that such positions are not possible landing sites for floating a phrase carrying a [S-Focus] feature or that there is no such thing as successive-cyclic applications of pair Merge in principle.

- 11.

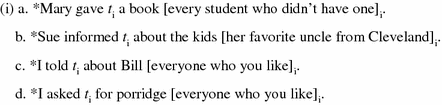

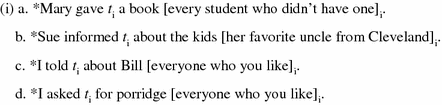

Lasnik and Saito (1992) note an example cited from Baltin (1982) that does not fit the pattern of acceptability given in (40):

(Baltin 1982: 17)

They take this example as an exception and those given in (40) as instantiating a general pattern that should be a target of syntactic explanation. I follow this strategy in the text, though this might not be the right way to go, given Haegeman’s (2012: 58) observation that “in English root wh-questions a pattern in which a fronted argument precedes a fronted wh-constituent gives rise to variable judgments.” Haegeman reproduces from the literature not only some examples that fit the pattern of acceptability given in (40) but also some others, as illustrated below, that do not fit this pattern.

(Haegeman 2012: 59)

There seem to be various factors that affect the relevant judgments. I have nothing interesting to say about this variability of judgments, leaving this matter open for further research. I am indebted to the editors for bringing Haegeman’s (2012) work to my attention.

- 12.

Things may not be that simple, however. Unlike topicalization and heavy XP shift, wh-movement involves a phrase, namely a wh-phrase, that can be detected as focus even though it does not undergo overt movement. In fact, there are so-called wh-in situ languages such as Japanese that do not require overt movement for wh-phrases. Thus, we may need another device to ensure that wh-movement must be overt in languages like English. See Sect. 3.2 for such a device in terms of labeling.

Recall that we have assumed in Sect. 3.2 that in situ wh-phrases in multiple wh-questions are licensed without movement:

Thus, in a multiple wh-question like (ii):

Thus, in a multiple wh-question like (ii): which park is licensed by way of being bound by who. This means under the present assumptions that such an in situ wh-phrase is not assigned [S-Focus]. Notice that it does not follow from this that such an in situ wh-phrase is not interpreted as focus in the LF component. Probably the licensing by way of (i) mediates a mechanism that propagates focused interpretation from one wh-phrase to another.

which park is licensed by way of being bound by who. This means under the present assumptions that such an in situ wh-phrase is not assigned [S-Focus]. Notice that it does not follow from this that such an in situ wh-phrase is not interpreted as focus in the LF component. Probably the licensing by way of (i) mediates a mechanism that propagates focused interpretation from one wh-phrase to another. - 13.

But CP-adjoined positions may not be possible landing sites for [S-Focus], as suggested in Footnote 10.

- 14.

In fact, the wa-phrase in (49a) is ambiguous between topic and contrastive -wa. See Hoji (1985) for the claim that the contrastive -wa phrase put in a sentence-initial position is derived by movement, possibly scrambling, from such an underlying structure as in (49b).

- 15.

Though cases of the contrastive -wa should be included in the relevant examples, it is hard to judge the scope ambiguity observed in (50) with -wa. I guess that this is why Aoyagi does not include -wa to make relevant examples. The scope ambiguity observed in (50) is also observed by Taglicht (1984) in English with only and even. I hope that the discussion in the text extends to such English FPs.

There is one caveat to be noted with (50). Aoyagi (1994) notes that although this example involves a Caseless FP phrase, the latter can be replaced by the Case marked FP phrase sinabita ringo-o-mo/-sae-o and in this case, it is hard to obtain the matrix scope interpretation. Further, Sano (2001) argues that some FPs such as -made ‘as far as’ do not allow the matrix scope interpretation. I must leave such ramifications aside.

- 16.

Notice that the covert movement in question is what I called inherently covert movement, since when a phrase carrying a [-WH-S-F] is accompanied by an FP, the option of overt movement is unavailable to it. See the relevant discussion around (38) in Sect. 3.2.

- 17.

Sano also attributes the unacceptability of the matrix reading of okane-sae to an intervention effect, though it remains to be seen whether the whole theory he assumes is compatible with that assumed here. See Sano (2001) for his original analysis of FP phrases and their licensing.

- 18.

In (65), to Susan is pair-merged with T’ to satisfy its [-WH-S-F]. There is another option to consider for satisfying this feature: pair-merging with v’. See below for the discussion of what happens in that case.

- 19.

- 20.

I am now showing the relevant derivation step by step, so strictly to Susan is pair-merged with TP before Bill is raised to Spec-TP. It is immaterial whether it is TP or T’ that to Susan is pair-merged with under the bare phrase structure framework.

- 21.

Abe and Hoshi (1997) argue that contrary to English gapping, Japanese gapping involves leftward movement. As they claim, this follows from the constraints on the direction of adjunction sites, since Japanese is a head-final language. See Abe and Hoshi (1997) for a variety of evidence to support this claim.

- 22.

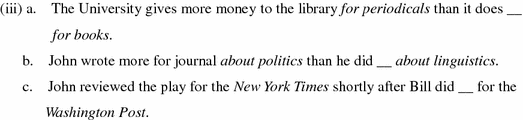

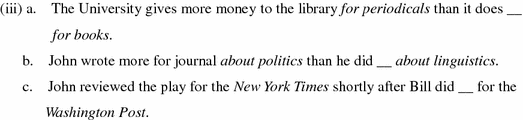

I am not sure whether the present analysis accommodates all the cases of gapping that involve three remnants. Larson (1990) doubts about the validity of the two-constituent test for gapping, providing the following example, which he attributes to Sag (1976):

(Sag 1976: 197)

It does not seem to be plausible to assume that such PP phrases as about his thesis/departmental politics can be base-generated in T’-adjoined position. See also Sag et al. (1985) for the same claim as Larson’s. Note that in fn. 6, I cited an example from Saito and Fukui (1998) that is acceptable even though it involves multiple rightward movement in a single clause. To the extent that there is a correlation in acceptability between multiple rightward movement and gapping with three remnants, it will lend support to the present analysis, but I must leave it aside whether this prediction is in fact borne out.

- 23.

The reason why Sag (1976) gives an independent name to this particular construction is that he considers that it should be dealt with differently from the gapping construction. Larson (1988) notes the possibility that this construction does not involve ellipsis, suggesting an alternative analysis according to which it is derived from VP conjunction plus across-the-board V-raising. It is beyond the scope of the present purpose to discuss this possibility in the text, and we simply assume that the LPD construction is just a special case of gapping. Note nonetheless that the arguments given in the text will lend support to this assumption. See Jackendoff (1990) and Larson (1990) for relevant discussions.

- 24.

It is also predicted under the present analysis that the first remnant of the LPD construction should show Subjacency effects while the second should show clause-bound effects. In fact, Abe and Hoshi (1997) examine relevant data to see if the prediction is borne out. Unfortunately, it does not seem that the judgments on the data are crystal-clear. For this reason, I do not examine this matter any further here.

- 25.

Notice that we are assuming here that on Friday is base-generated within V-projections. Otherwise, leftward movement of this phrase would violate the Last Resort Principle, since its [-WH-S-F] feature could be licensed in an adjoined position of v or T.

- 26.

We need to make sure if (97) overly rules out the structures we have assumed as legitimate in this section. As far as I can determine, no such problem will arise. I want to leave the verification of this to the reader, though.

- 27.

As standardly assumed, a deletion site is encoded with a feature like [Delete] in a syntactic structure, so that this information is available not only to PF but also to LF.

- 28.

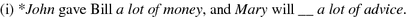

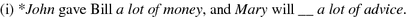

This analysis of pseudogapping owes much to Lasnik’s (1995a, 1999) insightful analysis of this construction, according to which its remnant sits in Spec-Agro, a position for accusative Case checking. Nonetheless, the present analysis differs crucially from his in that it also allows the option of a remnant being licensed in vP right-adjoined position. Thus, it cannot account for the following data, pointed out by Lasnik (1995a, 1999), if their grammatical status is as indicated:

(Lasnik 1999: 143)

This is because nothing goes wrong in the present analysis if the remnant a lot of advice is right-adjoined to vP. That such adjunction should be possible is indicated by the grammaticality of the following sentence:

However, I am not sure how secure the grammatical judgment given in (i) is. Lappin (1991), for instance, provides the following examples as grammatical:

(Lappin 1991: 322)

Lappin notes that pseudogapping constructions are more comfortable in subordination than in coordination. Then, the difference in acceptability between the examples given in (iii) and that in (i) may be partly attributed to this factor. Taking into consideration the fact that pseudogapping is not only a marginal construction to begin with but also seems to involve many unknown factors, I will not pursue this construction any further here.

- 29.

Notice that the remnant phrases carrying [S-Focus] features in such elliptic constructions as gapping, stripping, LPD and pseudogapping discussed in the text are all interpreted as foci, in fact contrastive foci, irrespective of whether they are located in left-peripheral or right-peripheral positions. Hence, the relevant interpretive rules that assign proper interpretation to such remnant phrases in the LF component must be different from those that are involved in non-elliptic constructions; according to the latter rules, when a phrase carrying [-WH-S-F] is located in a left-peripheral position, it is interpreted as topic, and when it is located in a right-peripheral position, it is interpreted as focus. I speculate that the difference may be attributed to the fact that in such elliptic constructions, [S-Focus] features are assigned not only to the remnant phrases in the second conjuncts but also to the corresponding phrases in the first conjuncts. But I must leave it open exactly how such a feature distribution affects the interpretations of those phrases carrying [S-Focus] features.

- 30.

Rightward movement can take place from the subject position of the ECM construction to the matrix TP-adjoined position, as shown below [the example is taken from Lasnik and Saito (1991)]:

As noted in the discussion on (106a), in this case, the shifted DP his recent discovery about Gapping first undergoes overt raising to the matrix Spec-VP and then is pair-merged with the matrix TP, hence inducing no violation of MCL.

As noted in the discussion on (106a), in this case, the shifted DP his recent discovery about Gapping first undergoes overt raising to the matrix Spec-VP and then is pair-merged with the matrix TP, hence inducing no violation of MCL. - 31.

- 32.

It is not clear what effects are imposed upon interpretation in the LF or PF component apart from altering scope order when QPs carry [-WH-S-F]. I suggested at the beginning of this chapter that in English, a phrase occupying a right-peripheral position is interpreted as a focalized element. Then we want to claim that an inverse scope interpretation is available only when the lower QP gets focused. It is not clear, however, that this is the right observation of the data involved. It is beyond the scope of the present discussion to elaborate this matter further.

- 33.

The present analysis makes a further prediction with respect to the possibility of inverse scope readings. As noted in the previous section, in the double object construction, IO cannot undergo heavy NP shift, as shown below [sentences (ia,b) are taken from Pesetsky (1995: 259)]:

It is then predicted that in these configurations, IO cannot take scope over subject. Relevant examples are given below:

It is then predicted that in these configurations, IO cannot take scope over subject. Relevant examples are given below: According to the native speaker I consulted with, it seems to be the case that the inverse scope reading of the every-phrases is rather hard to obtain. Thus, to the extent that the facts are clear, they lend further support to the present analysis of inverse scope readings.

According to the native speaker I consulted with, it seems to be the case that the inverse scope reading of the every-phrases is rather hard to obtain. Thus, to the extent that the facts are clear, they lend further support to the present analysis of inverse scope readings. - 34.

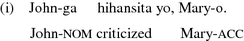

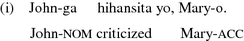

Though I argue in Abe (2015a) that a right-dislocation sentence such as the following involves focus movement:

I argue there that (i) has a bi-clausal structure in which the second clause involves an elliptic construction with leftward focus movement of Mary-o. It seems to be the case, then, that focus movement is available in Japanese elliptic constructions. See Abe and Hoshi (1997, 1999) for other such constructions.

I argue there that (i) has a bi-clausal structure in which the second clause involves an elliptic construction with leftward focus movement of Mary-o. It seems to be the case, then, that focus movement is available in Japanese elliptic constructions. See Abe and Hoshi (1997, 1999) for other such constructions. - 35.

It is beyond the scope of the present purpose to make a full discussion on alternative approaches to the (un)availability of inverse scope readings of QPs, but as long as the correlation between the availability of such inverse scope readings and that of focus movement triggered by [-WH-S-F] is empirically motivated, as witnessed by the contrast between English and Japanese as well as the English examples given in (124), this gives strong support to the present approach to the (un)availability of inverse scope readings of QPs. Recently, Bobaljik and Wurmbrand (2012) develop the idea that scope rigidity is correlated with the availability of scrambling, capturing this correlation in terms of violable constraints: when scrambling is available, scope order and word order must correlate, hence inducing scope rigidity, but if word order change is impossible by way of scrambling, the constraint that regulates this correlation is relaxed, which thus makes inverse scope readings possible. This mechanism of scope order properly captures the difference between Japanese and English with respect to the availability of inverse scope readings, but it is silent about why the availability of such readings correlates with that of focus movement, as illustrated in (124). Furthermore, there is an empirical question about the plausibility of the claim that scope rigidity is correlated with the availability of scrambling, as Huang (1982) observes that Chinese shows scope rigidity despite the fact that scrambling is unavailable to this language. Obviously, a counterexample from only one language would not necessarily discourage a Bobaljik and Wurmbrand (2012) type of approach, and I leave it open whether the present approach is really superior to this type of approach (or any other, for that matter).

References

Abe, Jun. 2001. Relativized X’-theory with symmetrical and asymmetrical structure. Minimalization of each module in generative grammar, Report for Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B)(2), 1–38. Graduate School of Humanities and Informatics, Nagoya University.

Abe, Jun. 2012. Scrambling and operator movement. Lingua 122: 66–91.

Abe, Jun. 2015a. The nature of scrambling and its resulting chains: Operator or mediator of various constructions. Ms.

Abe, Jun. 2015b. Head parameter as encoded in functional categories. Ms.

Abe, Jun, and Hiroto Hoshi. 1997. Gapping and P-stranding. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 6: 101–136.

Abe, Jun, and Hiroto Hoshi. 1999. Directionality of movement in ellipsis resolution in English and Japanese. In Fragments: Studies in ellipsis and gapping, ed. Shalom Lappin, and Elabbas Benmamoun, 193–226. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aoyagi, Hiroshi. 1994. On association with focus and scope of focus particles in Japanese. In Formal approaches to Japanese linguistics 1, MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 24, ed. Masatoshi Koizumi and Hiroyuki Ura, 23–44. Cambridge, MA: MITWPL.

Baltin, Mark R. 1982. A landing site theory of movement rules. Linguistic Inquiry 13: 1–38.

Bobaljik, Jonathan David. 1995. Morphosyntax: The syntax of verbal inflection. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Bobaljik, Jonathan David, and Susi Wurmbrand. 2012. Word order and scope: Transparent interfaces and the 3/4 signature. Linguistic Inquiry 43: 371–421.

Chomsky, Noam. 1973. Conditions on transformations. In A festschrift for Morris Halle, ed. Stephen R. Anderson and Paul Kiparsky, 232–286. New York: Holt, Reinhart and Winston.

Chomsky, Noam. 1993. A minimalist program for linguistic theory. In The view from Building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, ed. Ken Hale, and Sammuel J. Keyser, 1–52. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2004. Beyond explanatory adequacy. In Structure and beyond: The cartography of syntactic structures, vol. 3, ed. Adriana Belletti, 104–131. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational issues in linguistic theory: Essays in honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, ed. Robert Freiden, Carlos P. Otero, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta, 133–166. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fukui, Naoki. 1986. A theory of category projection and its applications. Doctoral dissertation, MIT. Revised version published as Theory of Projection in Syntax. CSLI Publications (1995), Stanford, California, distributed by University of Chicago Press.

Fukui, Naoki. 1993. Parameters and optionality. Linguistic Inquiry 24: 399–420.

Fukui, Naoki, and Margaret Speas. 1986. Specifiers and projection. In MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 8, ed. Naoki Fukui, Tova Rapoport, and Elizabeth Sagey, 128–172. Cambridge, MA: MITWPL.

Grimshaw, Jane. 2001. Extended projection and locality. In Lexical specification and insertion, ed. Peter Coopmans, Martin Everaert, and Jame Grimshaw, 115–133. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Haegeman, Liliane. 2012. Adverbial clauses, main clause phenomena, and composition of the left periphery: The cartography of syntactic structures, vol. 8. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hoji, Hajime. 1985. Logical form constraints and configurational structures in Japanese. Doctoral dissertation, University of Washington.

Hornstein, Nobert. 1984. Logic as grammar: An approach to meaning in natural language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Huang, C.-T. James. 1982. Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1971. Gapping and related rules. Linguistic Inquiry 2: 21–35.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1990. On Larson’s analysis of the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 21: 427–456.

Jayaseelan, K.A. 1990. Incomplete VP deletion and gapping. Linguistic Analysis 20: 64–81.

Kuno, Susumu. 1973. The structure of the Japanese language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lappin, Shalom. 1991. Concepts of Logical Form in linguistics and philosophy. In The Chomskyan turn, ed. Asa Kasher, 300–333. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell.

Larson, Richard K. 1988. On the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 19: 335–391.

Larson, Richard K. 1990. Double objects revisited: Reply to Jackendoff. Linguistic Inquiry 21: 589–632.

Lasnik, Howard. 1995a. A note on pseudogapping. In Papers on minimalist syntax, MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 27, ed. Rob Pensalfini and Hiroyuki Ura, 143–163. Cambridge MA: MITWPL.

Lasnik, Howard. 1995b. Verbal morphology: Syntactic Structures meets the Minimalist Program. In Evolution and revolution in linguistic theory: Essays in honor of Carlo Otero, ed. Héctor Campos and Paula Kempchinsky, 251–275. Washington D. C.: Georgetown University Press.

Lasnik, Howard. 1999. Pseudogapping puzzles. In Fragments: Studies in ellipsis and gapping, ed. Shalom Lappin, and Elabbas Benmamoun, 141–174. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lasnik, Howard, and Mamoru Saito. 1991. Curious correlations between configurations licensing (or failing to license) HNPShift and those for gapping. Note: University of Connecticut.

Lasnik, Howard, and Mamoru Saito. 1992. Move α: Conditions on its application and output. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Pesetsky, David. 1982. Paths and categories. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Pesetsky, David. 1995. Zero syntax: Experiencers and cascades. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Postal, Paul M. 1974. On raising: One rule of English grammar and its theoretical implications. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1976. The syntactic domain of anaphora. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1991. Elliptic conjunctions—Non-quantificational LF. In The Chomskyan turn, ed. Asa Kasher, 360–384. Cambridge MA: Blackwell.

Ross, John. 1967. Constraints on variables in syntax. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Sag, Ivan A. 1976. Deletion and Logical Form. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Sag, Ivan A., Gerald Gazdar, Thomas Wasow, and Steven Weisler. 1985. Coordination and how to distinguish categories. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 3: 117–171.

Saito, Mamoru. 1985. Some asymmetries in Japanese and their theoretical implications. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Saito, Mamoru. 1991. Extraposition and parasitic gaps. In Interdisciplinary approaches to language: Essays in honor of S.-Y. Kuroda, ed. Carol Georgopoulos and Roberta Ishihara, 467–486. Dordrecht: Foris.

Saito, Mamoru, and Naoki Fukui. 1998. Order in phrase structure and movement. Linguistic Inquiry 29: 439–474.

Sano, Masaki. 2001. On the scope of some focus particles and their interaction with causatives, adverbs, and subjects in Japanese. English Linguistics 18: 1–31.

Taglicht, Josef. 1984. Message and emphasis: On focus and scope in English. London: Longman.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix Focus Movement and QR

Appendix Focus Movement and QR

I have argued above that the clause-boundedness effects observed with rightward movement are derived from MCL: a Float operation cannot take place across a clause boundary since in that case, it would skip a possible landing site . However, as Postal (1974) notes, rightward movement is not strictly clause-bound, but it violates this restriction when the clause involved is infinitival, as shown below:

(Postal 1974: 92)

However, if an overt subject appears in the embedded infinitival clause in (115), the resulting sentence becomes ill-formed, as shown below:

I have suggested in the previous section that in such a case as (115), “reanalysis” takes place in such a way that the embedded V moves all the way up to the matrix V. This makes any two positions belonging to either the matrix or the embedded TP equidistant from any lower position. Thus, when the DP exactly what happened to Rosa Luxemburg in (115) undergoes Float to pair-merge with the matrix TP, it can skip the embedded TP-adjoined position without violating MCL, since this position and the matrix TP adjoined position are equidistant from the position from which this DP undergoes Float.Footnote 30

A curious correlation emerges between the locality of rightward movement and the scope interaction among QPs in English. As noted in Chap. 3, Reinhart (1976) claims that in a sentence such as the following:

everyone cannot take scope over someone, and she attributes this to the fact that someone asymmetrically c-commands everyone. There are many speakers, however, who allow the wide scope reading of everyone in such a case as (117). Noting this fact, Huang (1982) suggests that this reading is derived when the object QP undergoes rightward movement at LF to be shifted to a position high enough to c-command someone. That this type of analysis is on the right track is confirmed by the fact that the availability of such an inverse scope interpretation is constrained in the same way as the possibility of overt rightward movement for satisfying [-WH-S-F]. Note first that even those who allow the wide scope reading of everyone in (117) do not allow such a reading for the following sentence:

Further, it seems to be the case that these speakers see a contrast between the following sentences with respect to the availability of the wide scope reading of everyone Footnote 31:

Whereas everyone can take scope over someone in (119a), it cannot in (119b). These facts will receive a natural account if the inverse scope interpretation is possible only when rightward movement is available, as suggested by Huang (1982).

Recall that under our assumptions, (117) has the following representation:

In this representation, the [Scope] of everyone is licensed by means of being bound by the <Scope> of someone, and the latter feature in turn is licensed by QI. Thus, (120) represents the reading in which someone takes scope over everyone, since the former asymmetrically c-commands the latter. In order to obtain the inverse scope interpretation, we would have to covertly merge everyone with the whole TP, as shown below:

This representation is underivable, however, since the minimal Search[Scope] applied at TP cannot find everyone as its goal due to the intervening QP someone.

In order to capture the correlation of the possibility of rightward movement with that of an inverse scope reading, it is natural to assume that QPs can optionally carry [-WH-S-F].Footnote 32 If a subject QP carries this feature, no overt effects will be seen in CHL since this feature is satisfied in Spec-TP position, together with [Scope]. If a non-subject QP carries it, in contrast, it triggers pair Merge with v’ or T’. Thus, in (120), the object QP, when it carries [-WH-S-F], is pair-merged with either to vP or TP, undergoing string-vacuous rightward movement. Suppose that it is pair-merged with TP, as shown below:

This represents the stage of derivation in which everyone is pair-merged with TP to satisfy its [-WH-S-F], and someone is inserted into Spec-vP. Since the minimal Search for pair-merging everyone with TP is conducted with respect to [-WH-S-F], its [Scope] is simply carried along when everyone undergoes Float to satisfy its [-WH-S-F]. Suppose further that [Scope] can be satisfied when it is pair-merged with TP as well as when it is set-merged with it. Then, in (122), not only the [-WH-S-F] of everyone but also its [Scope] is licensed in the TP-pair-merged position. From this stage of derivation, someone moves to Spec-TP to satisfy the [EPP] feature of T, which may lead to the following structure:

In this derivation, the <Scope> of someone is left behind when this QP moves to Spec-TP, hence asymmetrically c-commanded by the [Scope] of everyone. Thus, (123) represents the inverse scope reading of everyone. In this way, the above account correctly captures the fact that the inverse scope reading of everyone obtains only if it undergoes rightward movement.

It is, then, natural to conjecture that those who do not obtain such an inverse scope reading in a sentence such as (117) do not allow rightward movement to be involved in deriving this sentence. This can be attributed to the fact that string-vacuous movement is a marked option for satisfying [S-Focus] features. It seems to be true that focus phenomena are closely connected to PF interpretations, so that they usually require overt manifestation of their effects. Given this, it is not implausible to reason that some speakers do not allow string-vacuous movement for satisfying [-WH-S-F].

The present account straightforwardly explains the scope facts observed in (118) and (119), repeated below:

In (124a), pair-merging everyone with the embedded TP for satisfying its [-WH-S-F] does not help it to take scope over someone, since even in that case, it is still not located high enough to c-command someone. Under the present assumptions, (124b) may have the following representation when everyone carries a [WH-S-F] feature:

In this representation, everyone is pair-merged with the matrix TP to satisfy its [-WH-S-F]. The Float operation required for this pair Merge does not violate MCL, since as a result of reanalysis , every intermediate position available to this operation and its final landing site count as equidistant from the position from which this operation is applied. The [Scope] of everyone is carried along as a free ride in this Float operation, thereby being licensed in the matrix TP-pair-merged position. The <Scope> of someone, on the other hand, is left behind when it moves to Spec-TP, hence asymmetrically c-commanded by the [Scope] of everyone. Thus, (125) represents the inverse scope reading of everyone for sentence (124b).

(124c), in contrast, cannot have such a representation as in (125), since the Float operation required for pair-merging everyone with the matrix TP will violate MCL, skipping a possible landing site , namely, the embedded TP-pair-merged position. Note that this case does not involve reanalysis , so that the embedded TP-pair-merged position and the matrix one do not count as equidistant from the position from which the Float operation is applied. Hence MCL forces everyone to be pair-merged with the embedded TP for satisfying its [-WH-S-F], as shown in the following representation, in which everyone is pair-merged with the TP of the infinitival clause and John is inserted to Spec-vP:

In this representation, the [Scope] of everyone is licensed in this TP-pair-merged position. It follows, then, that everyone must take scope in the embedded infinitival clause in (124c), and hence cannot take scope over someone.Footnote 33

We have observed in Chap. 3 that in Japanese, an object QP cannot take scope over a subject QP in a sentence that has an underlying order, as illustrated below:

If the above analysis is correct, this fact will suggest that Japanese does not have the option of focus movement [=movement for satisfying [-WH-S-F]] being applied to an object QP to derive an inverse scope reading. This is exactly what we expect since, as we have seen above, Japanese exploits FPs such as -wa, -sae, and -mo rather than movement to mark topic and focus.Footnote 34 , Footnote 35 This will lead to the prediction that an object QP will be able to take scope over a subject QP when it bears an FP in Japanese, since in that case, its [Scope] will be carried along as a free ride in the Float operation for satisfying its [-WH-S-F]. This does not seem to be borne out, however:

This sentence does not allow the wide scope reading of sono hutari-no sensei ‘those two teachers’. Recall that FP phrases undergo covert movement to satisfy their [-WH-S-F]. Thus, under the present assumptions, (128) could have the following representation:

Since the minimal Search applied at TP is conducted with respect to [-WH-S-F], the [Scope] of sono hutari-no sensei-mo/-sae ‘even those two teachers’ should be able to be carried along as a free ride. I suggest that this free ride of a feature is available only when the Float operation in question is overt, as stated below:

Given this, the minimal Search applied at TP in (129) must be conducted with respect to [Scope] as well as [-WH-S-F], and hence it cannot find the object QP as its goal due to the intervening subject QP dareka ‘someone’. I do not have any good answer to the question why (130) holds, but this condition will capture the standardly observed fact that overt movement affects scopal phenomena of QPs and wh-phrases whereas covert movement does not.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Abe, J. (2017). Search and Float for Topicalization and Focalization. In: Minimalist Syntax for Quantifier Raising, Topicalization and Focus Movement: A Search and Float Approach for Internal Merge. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, vol 93. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47304-8_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47304-8_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-47303-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-47304-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)

In this derivation, John must go through the embedded Spec-TP to satisfy MCL, since even though the Case-feature of John is not actually licensed in this position, it counts as a possible landing site for floating John, given the assumption that any type of Spec-TP serves as such, irrespective of the inherent property of T.

In this derivation, John must go through the embedded Spec-TP to satisfy MCL, since even though the Case-feature of John is not actually licensed in this position, it counts as a possible landing site for floating John, given the assumption that any type of Spec-TP serves as such, irrespective of the inherent property of T.

Thus, in a multiple wh-question like (ii):

Thus, in a multiple wh-question like (ii): which park is licensed by way of being bound by who. This means under the present assumptions that such an in situ wh-phrase is not assigned [S-Focus]. Notice that it does not follow from this that such an in situ wh-phrase is not interpreted as focus in the LF component. Probably the licensing by way of (i) mediates a mechanism that propagates focused interpretation from one wh-phrase to another.

which park is licensed by way of being bound by who. This means under the present assumptions that such an in situ wh-phrase is not assigned [S-Focus]. Notice that it does not follow from this that such an in situ wh-phrase is not interpreted as focus in the LF component. Probably the licensing by way of (i) mediates a mechanism that propagates focused interpretation from one wh-phrase to another.

As noted in the discussion on (106a), in this case, the shifted DP his recent discovery about Gapping first undergoes overt raising to the matrix Spec-VP and then is pair-merged with the matrix TP, hence inducing no violation of MCL.

As noted in the discussion on (106a), in this case, the shifted DP his recent discovery about Gapping first undergoes overt raising to the matrix Spec-VP and then is pair-merged with the matrix TP, hence inducing no violation of MCL.

It is then predicted that in these configurations, IO cannot take scope over subject. Relevant examples are given below:

It is then predicted that in these configurations, IO cannot take scope over subject. Relevant examples are given below: According to the native speaker I consulted with, it seems to be the case that the inverse scope reading of the every-phrases is rather hard to obtain. Thus, to the extent that the facts are clear, they lend further support to the present analysis of inverse scope readings.

According to the native speaker I consulted with, it seems to be the case that the inverse scope reading of the every-phrases is rather hard to obtain. Thus, to the extent that the facts are clear, they lend further support to the present analysis of inverse scope readings. I argue there that (i) has a bi-clausal structure in which the second clause involves an elliptic construction with leftward focus movement of Mary-o. It seems to be the case, then, that focus movement is available in Japanese elliptic constructions. See Abe and Hoshi (

I argue there that (i) has a bi-clausal structure in which the second clause involves an elliptic construction with leftward focus movement of Mary-o. It seems to be the case, then, that focus movement is available in Japanese elliptic constructions. See Abe and Hoshi (