Abstract

A time-reversible cellular automaton can most easily be described by regarding its evolution law as a two-step process, for instance by first allowing the even sites to update, then the odd sites. The discrete Hamiltonian operator procedure of Chap. 19 may be used. Subsequently, we apply a perturbative algebra, starting from the Baker Campbell Hausdorff expansion.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

The fundamental notion of a cellular automaton was briefly introduced in Part I, Sect. 5.1. We here resume the discussion of constructing a quantum Hamiltonian for these classical systems, with the intention to arrive at some expression that may be compared with the Hamiltonian of a quantum field theory [110], resembling Eq. (20.6), with Hamiltonian density (20.7), and/or (20.14). In this chapter, we show that one can come very close, although, not surprisingly, we do hit upon difficulties that have not been completely resolved.

1 Local Time Reversibility by Switching from Even to Odd Sites and Back

Time reversibility is important for allowing us to perform simple mathematical manipulations. Without time reversibility, one would not be allowed to identify single states of an automaton with basis elements of a Hilbert space. Now this does not invalidate our ideas if time reversibility is not manifest; in that case one has to identify basis states in Hilbert space with information equivalence classes, as was explained in Sect. 7. The author does suspect that this more complicated situation might well be inevitable in our ultimate theories of the world, but we have to investigate the simpler models first. They are time reversible. Fortunately, there are rich classes of time reversible models that allow us to sharpen our analytical tools, before making our lives more complicated.

Useful models are obtained from systems where the evolution law \(U\) consists of two parts: \(U_{A}\) prescribes how to update all even lattice sites, and \(U_{B}\) gives the updates of the odd lattice sites. So we have \(U=U_{A}\cdot U_{B}\).

1.1 The Time Reversible Cellular Automaton

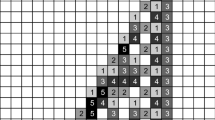

In Sect. 5.1, a very simple rule was introduced. The way it was phrased there, the data on two consecutive time layers were required to define the time evolution in the future direction as well as back towards the past—these automata are time reversible. Since, quite generally, most of our models work with single time layers that evolve towards the future or the past, we shrink the time variable by a factor 2. Then, one complete time step for this automaton consists of two procedures: one that updates all even sites only, in a simple, reversible manner, leaving the odd sites unchanged, while the procedure does depend on the data on the odd sites, and one that updates only the odd sites, while depending on the data at the even sites. The first of these operators is called \(U_{A}\). It is the operator product of all operations \(U_{A}(\vec{x})\), where \(\vec{x}\) are all even sites, and we take all these operations to commute:

The commutation is assured if \(U_{A}(\vec{x})\) depends only on its neighbours, which are odd, but not on the next-to-nearest neighbours, which are even again. Similarly, we have the operation at the odd sites:

while \([U_{A}(\vec{x}), U_{B}(\vec{y})]\ne0\) only if \(\vec{x}\) and \(\vec{y}\) are direct neighbours.

In general, \(U_{A}(\vec{x})\) and \(U_{B}(\vec{y})\) at any single site are sufficiently simple (often they are finite-dimensional, orthogonal matrices) that they are easy to write as exponentials:

\(A(\vec{x})\) and \(B(\vec{y})\) are defined to lie in the domain \([0,2\pi)\), or sometimes in the domain \((-\pi,\pi]\).

The advantage of this notation is that we can now writeFootnote 1

and the complete evolution operator for one time step \(\delta t=1\) can be written as

Let the data in a cell \(\vec{x}\) be called \(Q(\vec{x})\). In the case that the operation \(U_{A}(\vec{x})\) consists of a simple addition (either a plane addition or an addition modulo some integer \({N}\)) by a quantity \(\delta Q(Q(\vec{y}_{i}))\), where \(\vec{y}_{i}\) are the direct neighbours of \(\vec{x}\), then it is easy to write down explicitly the operators \(A(\vec{x})\) and \(B(\vec{y})\). Just introduce the translation operator

to find

The operator \(\eta(\vec{x})\) is not hard to analyse. Assume that we are in a field of additions modulo \(N\), as in Eq. (21.6). Go the basis of states \(|k\rangle_{\hbox{\tiny {U}}}\), with \(k= 0, 1,\ldots,N-1\), where the subscript \(\scriptstyle{\mathrm {U}}\) indicates that they are eigenstates of \(U_{\eta}\) and \(\eta\) (at the point \(\vec{x}\)):

We have

(if \(-{1\over 2}N< k\le{1\over 2}N\)), so we can define \(\eta\) by

mathematical manipulations that must look familiar now, see Eqs. (2.25) and (2.26) in Sect. 2.2.1.

Now \(\delta Q(\vec{y}_{i})\) does not commute with \(\eta(\vec{y}_{i})\), and in Eq. (21.7) our model assumes the sites \(\vec{y}_{i}\) to be only direct neighbours of \(\vec{x}\) and \(\vec{x}_{i}\) are only the direct neighbours of \(\vec{y}\). Therefore, all \(A(\vec{x})\) also commute with \(B(\vec{y})\) unless \(|\vec{x}-\vec{y} |=1\). This simplifies our discussion of the Hamiltonian \(H\) in Eq. (21.5).

1.2 The Discrete Classical Hamiltonian Model

In Sect. 19.4.4, we have seen how to generate a local discrete evolution law from a classical, discrete Hamiltonian formalism. Starting from a discrete, non negative Hamiltonian function \(H\), typically taking values \(N=0,1,2,\ldots\) , one searches for an evolution law that keeps this number invariant. This classical \(H\) may well be defined as a sum of local terms, so that we have a non negative discrete Hamiltonian density. It was decided that a local evolution law \(U(\vec{x})\) with the desired properties can be defined, after which one only has to decide in which order this local operation has to be applied to define a unique theory. In order to avoid spurious non-local behaviour, the following rule was proposed:

The evolution equations (e.o.m.) of the entire system over one time step \(\delta t\), are obtained by ordering the coordinates as follows: first update all even lattice sites, then update all odd lattice sites

(how exactly to choose the order within a given site is immaterial for our discussion). The advantage of this rule is that the \(U(\vec{x})\) over all even sites \(\vec{x}\) can be chosen all to commute, and the operators on all odd sites \(\vec{y}\) will also all commute with one another; the only non-commutativity then occurs between an evolution operator \(U(\vec{x})\) at an even site, and the operator \(U(\vec{y})\) at an adjacent site \(\vec{y}\).

Thus, this model ends up with exactly the same fundamental properties as the time reversible automaton introduced in Sect. 21.1.1: we have \(U_{A}\) as defined in Eq. (21.1) and \(U_{B}\) as in (21.2), followed by Eqs. (21.3)–(21.5).

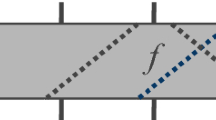

We conclude that, for model building, splitting a space–time lattice into the even and the odd sub lattices is a trick with wide applications. It does not mean that we should believe that the real world is also organized in a lattice system, where such a fundamental role is to be attributed to the even and odd sub lattices; it is merely a convenient tool for model building. We shall now discuss why this splitting does seem to lead us very close to a quantum field theory.

2 The Baker Campbell Hausdorff Expansion

The two models of the previous two subsections, the arbitrary cellular automaton and the discrete Hamiltonian model, are very closely related. They are both described by an evolution operator that consists of two steps, \(U_{A}\) and \(U_{B}\), or, \(U_{\mathrm{even}}\) and \(U_{\mathrm{odd}}\). The same general principles apply. We define \(A, A(\vec{x}), B\) and \(B(\vec{x})\) as in Eq. (21.4).

To compute the Hamiltonian \(H\), we may consider using the Baker Campbell Hausdorff expansion [71]:

a series that continues exclusively with commutators. Replacing \(P\) by \(-iA\), \(Q\) by \(-iB\) and \(R\) by \(-iH\), we find a series for \(H\) in the form of an infinite sequence of commutators. We noted at the end of the previous subsection that the commutators between the local operators \(A(\vec{x})\) and \(B(\vec{x} ')\) are non-vanishing only if \(\vec{x}\) and \(\vec{x} '\) are neighbours, \(|\vec{x}-\vec{x} '|=1\). Therefore, if we insert the sums (21.4) into Eq. (21.11), we obtain again a sum. Writing

so that

we find

where

The sums here are only over close neighbours, so that each term here can be regarded as a local Hamiltonian density term.

Note however, that as we proceed to collect higher terms of the expansion, more and more distant sites will eventually contribute; \(\mathcal{H} _{n}(\vec{r})\) will receive contributions from sites at distance \(n-1\) from the original point \(\vec{r}\).

Note furthermore that the expansion (21.14) is infinite, and convergence is not guaranteed; in fact, one may suspect it not to be valid at all, as soon as energies larger than the inverse of the time unit \(\delta t\) come into play. We will have to discuss that problem. But first an important observation that improves the expansion.

3 Conjugacy Classes

One might wonder what happens if we change the order of the even and the odd sites. We would get

instead of Eq. (21.5). Of course this expression could have been used just as well. In fact, it results from a very simple basis transformation: we went from the states \(|\psi\rangle\) to the states \(U_{B}|\psi\rangle\). As we stated repeatedly, we note that such basis transformations do not affect the physics.

This implies that we do not need to know exactly the operator \(U(\delta t)\) as defined in Eqs. (21.5) or (21.16), we need just any element of its conjugacy class. The conjugacy class is defined by the set of operators of the form

where \(G\) can be any unitary operator. Writing \(G=e^{F}\), where \(F\) is anti-Hermitian, we replace Eq. (21.11) by

so that

We can now decide to choose \(F\) in such a way that the resulting expression becomes as simple as possible. For one, interchanging \(P\) and \(Q\) should not matter. Secondly, replacing \(P\) and \(Q\) by \(-P\) and \(-Q\) should give \(-\tilde{R}\), because then we are looking at the inverse of Eq. (21.19).

The calculations simplify if we write

(or, in the previous section, \(S=-{1\over 2}i K,\ D=-{1\over 2}i L\) ). With

we can now demand \(F\) to be such that:

which means that \(\tilde{R}\) contains only even powers of \(D\) and odd powers of \(S\). We can furthermore demand that \(\tilde{R}\) only contains terms that are commutators of \(D\) with something; contributions that are commutators of \(S\) with something can be removed iteratively by judicious choices of \(F\).

Using these constraints, one finds a function \(F(S,D)\) and \(\tilde {R}(S,D)\). First let us introduce a short hand notation. All our expressions will consist of repeated commutators. Therefore we introduce the notation

Subsequently, we even drop the accolades \(\{\ \}\). So when we write

Then, with \(F=-{1\over 2}D+{1\over 24}S^{2}D+\cdots\), one finds

There are three remarks to be added to this result:

-

(1)

It is much more compact than the original BCH expansion; already the first two terms of the expansion (21.24) correspond to all terms shown in Eq. (21.11).

-

(2)

The coefficients appear to be much smaller than the ones in (21.11), considering the factors \(1/2\) in Eqs. (21.20) that have to be included. We found that, in general, sizeable cancellations occur between the coefficients in (21.11).

-

(3)

However, there is no reason to suspect that the series will actually converge any better. The definitions of \(F\) and \(\tilde {R}\) may be expected to generate singularities when \(P\) and \(Q\), or \(S\) and \(D\) reach values where \(e^{\tilde{R}}\) obtains eigenvalues that return to one, so, for finite matrices, the radius of convergence is expected to be of the order \(2\pi\).

In this representation, all terms \(\mathcal{H}_{n}(\vec{r})\) in Eq. (21.14) with \(n\) even, vanish. Using

one now arrives at the Hamiltonian in the new basis:

and \(\tilde{\mathcal{H}}_{7}\) follows from the second line of Eq. (21.24).

All these commutators are only non-vanishing if the coordinates \(\vec{s}_{1}\), \(\vec{s}_{2}\), etc., are all neighbours of the coordinate \(\vec{r}\). It is true that, in the higher order terms, next-to-nearest neighbours may enter, but still, one may observe that these operators all are local functions of the ‘fields’ \(Q(\vec{x}, t)\), and thus we arrive at a Hamiltonian \(H\) that can be regarded as the sum over \(d\)-dimensional space of a Hamiltonian density \(\mathcal{H}(\vec{x})\), which has the property that

At every finite order of the series, the Hamiltonian density \(\mathcal{H}(\vec{x})\) is a finite-dimensional Hermitian matrix, and therefore, it will have a lowest eigenvalue \(h\). In a large but finite volume \(V\), the total Hamiltonian \(H\) will therefore also have a lowest eigenvalue, obeying

However, it was tacitly assumed that the Baker–Campbell–Hausdorff formula converges. This is usually not the case. One can argue that the series may perhaps converge if sandwiched between two eigenstates \(|E_{1}\rangle\) and \(|E_{2}\rangle\) of \(H\), where \(E_{1}\) and \(E_{2}\) are the eigenvalues, that obey

We cannot exclude that the resulting effective quantum field theory will depend quite non-trivially on the number of Baker–Campbell–Hausdorff terms that are kept in the expansion.

The Hamiltonian density (21.26) may appear to be quite complex and unsuitable to serve as a quantum field theory model, but it is here that we actually expect that the renormalization group will thoroughly cleanse our Hamiltonian, by invoking the mechanism described at the end of Sect. 20.8.

Notes

- 1.

The sign in the exponents is chosen such that the operators \(A\) and \(B\) act as Hamiltonians themselves.

References

A.A. Sagle, R.E. Walde, Introduction to Lie Groups and Lie Algebras (Academic Press, New York, 1973). ISBN 0-12-614-550-4

Papers by the author that are related to the subject of this work:

G. ’t Hooft, Classical cellular automata and quantum field theory, in Proceedings of the Conference in Honour of Murray Gell-Mann’s 80th Birthday, ed. by H. Fritzsch, K.K. Phua. Quantum Mechanics, Elementary Particles, Quantum Cosmology and Complexity, Singapore, February 2010 (World Scientific, Singapore, 2010), pp. 397–408; repr. in: Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 25(23), 4385–4396 (2010)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, a link is provided to the Creative Commons license and any changes made are indicated.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work's Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

’t Hooft, G. (2016). The Cellular Automaton. In: The Cellular Automaton Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Fundamental Theories of Physics, vol 185. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41285-6_21

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-41285-6_21

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-41284-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-41285-6

eBook Packages: Physics and AstronomyPhysics and Astronomy (R0)