Abstract

Motor planning allows us to conceive, plan, and initiate skilled motor behaviors. Motor planning involves activity distributed widely across the cortex. How this activity dynamically comes together to guide movement remains an unsolved problem. We study motor planning in mice performing a tactile decision behavior. Head-fixed mice discriminate object locations with their whiskers and report their choice by directional licking (“lick left”/“lick right”). A short-term memory component separates tactile “sensation” and “action” into distinct epochs. Using loss-of-function experiments, cell-type specific electrophysiology, and cellular imaging, we delineate when and how activity in specific brain areas and cell types drives motor planning in mice. Our results suggest that information flows serially from sensory to motor areas during motor planning. The motor cortex circuit maintains the motor plan during short-term memory and translates the motor plan into motor commands that drive the upcoming directional licking.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

With a half a second’s planning, we rapidly carry out complex sequences of movements. Motor planning refers to our ability to conceive, plan, and initiate a skilled motor behavior. During motor planning, sensory information must be integrated to inform the appropriate motor responses. Behaviorally relevant information must be kept in short-term memory. Thus the process of motor planning taps into multiple aspects of flexible behavior and offers a way of studying the mental processes that ultimately culminate in a movement, hence a window into cognition.

A neural correlate of motor planning was first reported in humans as a deflection in EEG recordings, over motor and parietal cortex, which anticipates voluntary movements (a.k.a. Bereitschaftspotential; Deecke et al. 1976). The EEG signal appears long before the onset of the movement and hundreds of milliseconds before the subjects are aware of their desire to move (Libet 1985). The neural correlates of motor planning were discovered in the primate motor cortex by Tanji and Evarts (1976), who described neurons that discharged persistently before an instructed movement. This persistent activity ramped up shortly after the instruction, long before the movement onset, and predicted specific types of future movements. These findings opened the possibility of studying the mechanisms of motor planning at the level of neural circuits (Riehle and Requin 1989; Crutcher and Alexander 1990; Turner and DeLong 2000; Shenoy et al. 2013).

Behavioral paradigms in rodents are rapidly developing, and it is possible to train mice in behavioral tasks that dissociate planning and movement in time, analogous to the tasks used in primates (Guo et al. 2014a, b). The mouse is a genetically tractable organism, providing access to defined cell types for recordings and perturbations (Luo et al. 2008; O’Connor et al. 2009). In addition, the lissencephalic macrostructure of the mouse brain allows unobstructed access to a large fraction of the brain for functional analysis. We study motor planning in the context of a tactile decision behavior (Guo et al. 2014a; Li et al. 2015). Mice measure the location of an object using their whiskers and report their judgment by directional licking. We delineate when and how activity in specific cortical regions areas drives the tactile decision behavior in mice. New recording and perturbation methods are beginning to reveal the circuit mechanisms underlying motor planning that, in turn, will shed light on the biophysics of flexible behavior.

Head-Fixed Tactile Decision Behavior and Involved Cortical Regions

We developed a tactile decision task to track the flow of information in cortex during motor planning (Guo et al. 2014a; Li et al. 2015). Head-fixed mice measured the location of a pole using their whiskers and reported their decisions about object location with directional licking (Fig. 1a). In each trial, the pole was presented in one of two positions (anterior or posterior) during a sample epoch (1.3 s; Fig. 1b). During a subsequent delay epoch (1.3 s), the mice planned the upcoming response. An auditory go cue (0.1 s) signaled the beginning of the response epoch, when the mice reported the perceived pole position by licking one of two lickports (posterior → “lick right”, anterior → “lick left”). The mice achieved high levels of performance (~80 % correct). Responses before the go cue were rare (~13 %). They performed the tactile decision behavior across many sessions (up to 85 sessions, >400 trials per session), yielding tens of thousands of trials per mouse. The large number of trials allowed us to use optogenetic silencing to identify the cortical regions involved in an unbiased manner on a cortex-wide scale.

Mapping the cortical regions underlying tactile decision behavior. (a) Head-fixed mouse responding “lick right” or “lick left” based on pole location. (b) The pole was within reach during the sample epoch. Mice responded with licking after a delay and an auditory go cue. (c) Fifty-five cortical locations were tested in loss-of-function experiments during different behavioral epochs. Top, photoinhibition during sample (left) and delay (right) epochs. Bottom, cortical regions involved in the tactile decision behavior during sample (left) and delay (right) epochs in “lick right” trials. Color codes for the change in performance (%) under photoinhibition relative to control performance. Circle size codes for significance (p values, from small to large; >0.025, <0.025, <0.01, <0.001). Figure adapted from Guo et al. (2014a)

To achieve powerful cortical inactivation, we used transgenic mice expressing Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) in cortical GABAergic interneurons. This photoinhibition silenced millimeter-size tissue volumes by photostimulating through the intact skull (85 % activity reduction) with time resolutions on the order of 100 ms. We developed a scanning laser system to survey the neocortex for regions driving behavior during specific behavioral epochs. First, we outfitted the mice with a clear-skull cap preparation that provided optical access to half of the neocortex. A scanning system targeted photostimuli in a random access manner. Head-fixation and precise control of the laser position allowed each mouse to be tested repeatedly across multiple behavioral sessions. We tested 55 evenly spaced cortical volumes in sensory, motor, and parietal cortex for their involvement in the behavior by applying photoinhibition during specific behavioral epochs (Fig. 1c).

Inactivation of most cortical volumes did not cause any behavioral change. Inactivating vibrissal primary somatosensory cortex (vS1, “barrel cortex”) caused deficits in object location discrimination. The effect was temporally specific: inactivation during the delay epoch produced a much smaller deficit, suggesting that tactile information was transferred out of the vS1 during the sample epoch (Fig. 1c). During the delay epoch, preceding the motor response, inactivation of an anterior lateral region of the motor cortex (ALM) biased the upcoming movement (Fig. 1c). We used silicon probes to record single units from vS1 and ALM in mice performing the tactile decision behavior. Single unit recordings supported the photoinhibition experiments: a large fraction of neurons in vS1 showed object location-dependent activity during the sample epoch, whereas the majority of neurons in ALM showed movement-specific preparatory activity and peri-movement during the delay and response epochs. These results begin to outline the information flow in mouse cortex involved in the tactile decision behavior. The information flow is largely consistent with a serial scheme, where information is passed from sensory areas to motor areas during motor planning (Guo et al. 2014a).

Premotor Dynamics Underlying Motor Planning

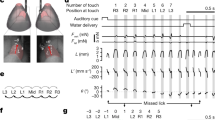

A large fraction (>70 %) of ALM neurons significantly distinguished upcoming movements during at least one of the trial epochs (p < 0.05, two-tailed t-test; Fig. 2a). On error trials, when mice licked in the opposite direction to the instruction provided by object location (Fig. 1a), most ALM neuron activities predicted the licking direction (Guo et al. 2014a; Li et al. 2015). Such movement-specific activity is consistent with a role in planning and driving movements (Fig. 1c). Interestingly, the preparatory activity in ALM was not static but evolved with complex dynamics: subsets of neurons showed selective activity during the sample epoch whereas other neurons showed “bumps” of activity during different times of the delay epoch (Fig. 2a). Despite these fluctuating responses at the level of the single neurons, selectivity for the upcoming movement remained stable at the level of the population (Fig. 2b). On average, selectivity emerged in the sample epoch and ramped up throughout the delay epoch, reaching a maximum at the beginning of the response epoch (Fig. 2b). This ramping activity in ALM during the delay epoch is similar to the ramping activity reported in frontal (Hanes and Schall 1996; Murakami et al. 2014), parietal (Roitman and Shadlen 2002; Maimon and Assad 2006; Harvey et al. 2012), and motor cortex (Erlich et al. 2011; Thura and Cisek 2014), anticipating voluntary movements in primates and rodents. The ALM preparatory activity could provide a substrate for the maintenance of the motor plan during the delay epoch. Information about the upcoming movement is likely coded at the level of the population (Laurent 2002; Harvey et al. 2012; Shenoy et al. 2013; Murakami and Mainen 2015). Consistent with a distributed code, we found that spatially intermingled ALM neurons in each hemisphere have a preference for either contra- or ipsi-lateral movements in roughly equal proportions (Li et al. 2015).

Head-fixed tactile decision behavior and involved cortical regions. (a) Nine examples of ALM neurons. Top, spike raster. Bottom, PSTH. Correct “lick right” (blue) and “lick left” (red) trials only. Dashed lines, behavioral epochs. (b) Average ALM population selectivity in spike rate (± s.e.m. across neurons, bootstrap). Selectivity is the difference in spike rate between the preferred and non-preferred movements. Time zero is the onset of the go cue. Averaging window, 200 ms

The preparatory activity encodes upcoming movement, yet it does not cause movement during planning. How does preparatory activity evolve into commands that descend to motor centers to trigger movement? Paradoxically, ALM neurons in each hemisphere have a preference for contra- or ipsi-lateral movements in roughly equal proportions, yet unilateral inactivation of ALM biased the upcoming movement to the ipsi-lateral direction. How does silencing a brain area with non-lateralized selectivity cause a directional movement bias? We measured neuronal activity within hierarchically organized ALM circuits. ALM projection neurons include two major classes: intratelencephalic (IT) neurons that project to other cortical areas and pyramidal tract (PT) neurons that project out of the cortex, including to motor-related areas in the brainstem (Komiyama et al. 2010; Shepherd 2013). IT neurons connect to other IT neurons and excite PT neurons, but not vice versa. PT neurons are thus at the output end of the local ALM circuit (Morishima and Kawaguchi 2006; Brown and Hestrin 2009; Kiritani et al. 2012; Shepherd 2013). We recorded activity from identified IT and PT neurons using cell-type specific electrophysiology and two photon imaging. We found that ALM IT neurons have mixed preparatory activity for both ipsi- and contra-lateral movements. Contra-lateral population activity in PT neurons arose late during the delay epoch to drive directional licking. To test the causal role of the PT neuron population activity in driving movements, we manipulated PT neurons by expressing ChR2 in mouse lines selectively expressing cre in these neurons. Weak activation of the PT neurons during movement planning could “write-in” specific motor plans that resulted in contra-lateral licking movements. These results suggest that, during movement planning, distributed preparatory activity in IT neuron networks is converted into a movement command in PT neurons (‘output-potent’ activity; Kaufman et al. 2014), which ultimately triggers directional movements (Li et al. 2015).

Open Questions

Several key questions remain unsolved. What circuit mechanisms are responsible for the maintenance of motor plan during short-term memory? How is sensory information integrated into the motor plan? How do the basal ganglia and motor thalamus interact with cortical regions during motor planning? Answering these questions will require recordings and manipulation of specific cell types. Importantly, architectural and cell type information must be incorporated into models of cortical dynamics. Tools to manipulate projections between brain regions are needed to study the interactions between brain regions. Finally, there is still a long way to go in developing richer behavioral paradigms that tap into the capabilities of the mammalian brain.

References

Brown SP, Hestrin S (2009) Intracortical circuits of pyramidal neurons reflect their long-range axonal targets. Nature 457:1133–1136

Crutcher MD, Alexander GE (1990) Movement-related neuronal activity selectively coding either direction or muscle pattern in three motor areas of the monkey. J Neurophysiol 64:151–163

Deecke L, Grozinger B, Kornhuber HH (1976) Voluntary finger movement in man: cerebral potentials and theory. Biol Cybern 23:99–119

Erlich JC, Bialek M, Brody CD (2011) A cortical substrate for memory-guided orienting in the rat. Neuron 72:330–343

Guo ZV, Li N, Huber D, Ophir E, Gutnisky DA, Ting JT, Feng G, Svoboda K (2014a) Flow of cortical activity underlying a tactile decision in mice. Neuron 81:179–194

Guo ZV, Hires SA, Li N, O’Connor DH, Komiyama T, Ophir E, Huber D, Bonardi C, Morandell K, Gutnisky D, Peron S, Xu NL, Cox J, Svoboda K (2014b) Procedures for behavioral experiments in head-fixed mice. PLoS One 9:e88678

Hanes DP, Schall JD (1996) Neural control of voluntary movement initiation. Science 274:427–430

Harvey CD, Coen P, Tank DW (2012) Choice-specific sequences in parietal cortex during a virtual-navigation decision task. Nature 484:62–68

Kaufman MT, Churchland MM, Ryu SI, Shenoy KV (2014) Cortical activity in the null space: permitting preparation without movement. Nat Neurosci 17:440–448

Kiritani T, Wickersham IR, Seung HS, Shepherd GM (2012) Hierarchical connectivity and connection-specific dynamics in the corticospinal-corticostriatal microcircuit in mouse motor cortex. J Neurosci 32:4992–5001

Komiyama T, Sato TR, O’Connor DH, Zhang YX, Huber D, Hooks BM, Gabitto M, Svoboda K (2010) Learning-related fine-scale specificity imaged in motor cortex circuits of behaving mice. Nature 464:1182–1186

Laurent G (2002) Olfactory network dynamics and the coding of multidimensional signals. Nat Rev Neurosci 3:884–895

Li N, Chen TW, Guo ZV, Gerfen CR, Svoboda K (2015) A motor cortex circuit for motor planning and movement. Nature 519:51–56

Libet B (1985) Unconscious cerebral initiative and the role of conscious will in voluntary action. Behav Brain Sci 8:529–539

Luo L, Callaway EM, Svoboda K (2008) Genetic dissection of neural circuits. Neuron 57:634–660

Maimon G, Assad JA (2006) A cognitive signal for the proactive timing of action in macaque LIP. Nat Neurosci 9:948–955

Morishima M, Kawaguchi Y (2006) Recurrent connection patterns of corticostriatal pyramidal cells in frontal cortex. J Neurosci 26:4394–4405

Murakami M, Mainen ZF (2015) Preparing and selecting actions with neural populations: toward cortical circuit mechanisms. Curr Opin Neurobiol 33C:40–46

Murakami M, Vicente MI, Costa GM, Mainen ZF (2014) Neural antecedents of self-initiated actions in secondary motor cortex. Nat Neurosci 17:1574–1582

O’Connor DH, Huber D, Svoboda K (2009) Reverse engineering the mouse brain. Nature 461:923–929

Riehle A, Requin J (1989) Monkey primary motor and premotor cortex: single-cell activity related to prior information about direction and extent of an intended movement. J Neurophysiol 61:534–549

Roitman JD, Shadlen MN (2002) Response of neurons in the lateral intraparietal area during a combined visual discrimination reaction time task. J Neurosci 22:9475–9489

Shenoy KV, Sahani M, Churchland MM (2013) Cortical control of arm movements: a dynamical systems perspective. Annu Rev Neurosci 36:337–359

Shepherd GM (2013) Corticostriatal connectivity and its role in disease. Nat Rev Neurosci 14:278–291

Tanji J, Evarts EV (1976) Anticipatory activity of motor cortex neurons in relation to direction of an intended movement. J Neurophysiol 39:1062–1068

Thura D, Cisek P (2014) Deliberation and commitment in the premotor and primary motor cortex during dynamic decision making. Neuron 81:1401–1416

Turner RS, DeLong MR (2000) Corticostriatal activity in primary motor cortex of the macaque. J Neurosci 20:7096–7108

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Howard Hughes Medical Institute. N.L. is a Helen Hay Whitney Foundation postdoctoral fellow.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/) which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Li, N., Guo, Z.V., Chen, TW., Svoboda, K. (2016). Flow of Information Underlying a Tactile Decision in Mice. In: Buzsáki, G., Christen, Y. (eds) Micro-, Meso- and Macro-Dynamics of the Brain. Research and Perspectives in Neurosciences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28802-4_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28802-4_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-28801-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-28802-4

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)