Abstract

The world faces a new food economy that likely involves both higher and more volatile food prices; evidence of both conditions was clear in 2007/08 and 2011. After the food price crisis of 2007/08, food prices started rising again in June 2010, with international prices of maize and wheat roughly doubling by May 2011. This situation imposed several challenges. In the short run, the global food supply is relatively inelastic, leading to shortages and amplifying the impact of any shock. The poor are hit the hardest. In the long run, the goal should be to achieve food security. The drivers that have increased food demand in the last few years are likely to persist (and even expand). Thus, there is a significant role for international organizations like the World Bank, IFAD, AFD, and the IADB to play in increasing the countries’ capacity to cope with this new world scenario and in promoting appropriate policies that will help to minimize the adverse effects of the increase in prices and price volatility, as well as to avoid exacerbating the crisis.

In this regard, this chapter describes some of the most important official policies that international organizations prescribed to different countries during the food crisis of 2007/08. In addition, it compares those policies to the scientific evidence on their potential costs and benefits. The review focuses on the short-term, medium-, and long-term policies. In terms of short-term policies, two mechanisms are emphasized: support for the poor and price stabilization (with an emphasis on trade restrictions and food reserves). In terms of medium- and long-term policies, we focus on the recommendations linked to increasing agricultural productivity through productivity gains and elimination of postharvest losses.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

JEL Codes

1 Introduction

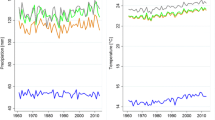

Food prices have increased significantly in the past few years, with particularly sharp spikes seen during the 2007/08 season (see Fig. 19.1). There is some agreement on the causes of such price increases: (a) weather shocks that negatively affected agricultural production; (b) soaring energy and fertilizer costs; (c) rapidly growing income in developing countries, especially in China and India; (d) the devaluation of the dollar against most major currencies; (e) increasing demand for biofuels; and (f) changes in land use patterns. While there is no consensus on the relative importance of each of these culprits, it is widely agreed that most of these factors will further increase food prices in the medium and long run. Prices may become more volatile as well, as evidenced by the subsequent food crisis in 2010. Climate change will induce more weather variability, leading to erratic production patterns. Moreover, the volatile nature of the market is likely to induce possible speculation and exacerbating price spikes. Additionally, in an effort to shield themselves from price fluctuations, different countries may implement isolating policies, further exacerbating volatility.

Looking at the volatility at global level is important because, although the food price spikes of 2008 and 2011 did not reach the heights of the 1970s in real terms as shown in Fig. 19.2, price volatility—the amplitude of price movements over a particular period of time—has been at its highest level in the past 15 years.

High and volatile food prices are two different phenomena with distinct implications for consumers and producers as detailed in Torero (2012). Finally, increased price volatility over time can also generate larger profits for investors, drawing new players into the market for agricultural commodities. Increased price volatility may thus lead to increased—and potentially speculative—trading that in turn can exacerbate price swings further.

This situation imposes several challenges. In the short run, the global food supply is relatively inelastic, leading to shortages and amplifying the impact of any shock. The poorest populations are the ones hit the hardest.Footnote 1 As a large share of their income is already being devoted to food, the poor will likely be forced to reduce their (already low) consumption. Infants and children may suffer lifelong consequences if they experience serious nutritional deficits during their early years. Thus, the short-term priority should be to provide temporary relief for vulnerable groups.

In the long run, the goal should be to achieve food security.Footnote 2 The drivers that have increased food demand in the last few years are likely to persist (and even expand). Thus, there will be escalating pressure to meet these demand requirements. Unfortunately, increases in agricultural productivity have been relatively meager in recent years. In this line, “the average annual rate of growth of cereal yields in developing countries fell steadily from 3 % in the late 1970s to less than 1 % currently, a rate less than that of population growth and much less than the rise of the use of cereals for other things besides direct use of food” (Delgado et al. 2010, p 2).

There is a wide array of options to achieve these short- and long-term objectives, and there are no one-size-fits-all policies. Most policies come with significant trade-offs, and each government must carefully weigh the benefits and costs they would face. For example, governments might try to make food more readily available by reducing food prices through price interventions. While this policy might achieve its short-term goal, it can potentially entail fiscal deficits and discourage domestic farmers’ production. Other policies not only have domestic consequences but can entail side effects for other countries. In their efforts to insulate themselves from international price fluctuations, some countries might impose trade restrictions; if a country is a large food exporter, the government might impose export taxes, quantitative restrictions, or even export bans. Albeit increasing domestic supply and lowering national prices, these policies would reduce the exported excess supply, induce even higher international prices, and hurt other nations. In addition, the “right” policies depend on the particular institutional development of a country. Middle-income countries might already have safety networks for vulnerable populations which can trigger prompt aid to those most in need in times of crisis. However, countries with lower incomes do not have such mechanisms readily available. Finally, the effectiveness of different policies will vary depending on the market characteristics of the commodity in which the government is intervening (i.e., the market structure for wheat is very different from that of rice, which is different from that of soybeans, etc.).

In this regard, this chapter describes some of the most important policies of the International Organizations like the World Bank, IFAD, AFD, and the IADB have prescribed to different countries during the food crisis of 2007/08. The understanding of such policies is important for at least three reasons. First, food crises are very sensitive episodes that affect the basic needs of entire populations, especially those of the world’s poorest countries. As such, they require timely and sensible measures. Second, increasing food prices and price volatility are likely to remain an important challenge in the medium and long run. Third, food policies are usually complex; they need to be assessed to consider their domestic impact, the trade-offs that they entail with respect to other objectives, their consequences for other countries, and their feasibility in particular contexts.

This chapter is divided into five sections (excluding the introduction). The second section analyzes a series of policies recommended by international organizations during the 2007/08 crisis and the policies recommended at the G8 Meeting of Finance Ministers in Osaka, June 13–14, 2008. The third section analyzes the policy recommendations which came out after the 2007/08 crisis and which were the result of research work done by the same international organizations. First, some short-term policies are analyzed in which two mechanisms are emphasized: support for the poor and price stabilization (with an emphasis on trade restrictions and food reserves). Second, medium- and long-term policies to increase agricultural productivity, through productivity gains and elimination of postharvest losses, are discussed. The fourth section describes specific loans and policies prescribed for selected countries during the 2007/08 food crisis. It analyzes their consistency and cohesiveness when contrasted with the general policies that some International Organizations formally recommended as well as with those policies that were recommended after 2008. The final section summarizes and presents some concluding remarks.

2 Proposed Policies and the G8 Summit

In this section, a detailed description of the policies officially proposed and the G8’s document prepared for the Ministers of Finance Meeting in 2008 (Table 19.1 presents a summary of all these policies) are presented. These policies can be classified either as short-term policies or as medium- and long-term policies. Specifically, within the short-term policies, we identify two groups of policies: (a) short-term support for the poorest and (b) price stabilization policies.

2.1 Short-Term Policies (Social Protection and Trade Policies)

2.1.1 Short-Term Support for the Poorest

Governments’ short-term objective is to increase access to food, especially for the most vulnerable shares of their population. In this sense, policies should provide targeted short-term subsidies to those in the most distress. Countries that already have Targeted Cash Transfer (TCT) and Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) programs in place can scale them up and increase the subsidies they provide (World Bank 2008). TCTs provide additional income to poor households with children or disabled or elderly members. CCTs provide the same benefits but are contingent on some conditionality (which usually encompasses an educational, nutritional, or health requirement). These approaches of cash transfer constitute first-best responses for several reasons: (a) they prioritize assistance for targeted groups, (b) they do not entail additional costs of food storage and transportation, (c) they do not distort food markets, and (d) in the case of CCTs, they explicitly prevent human capital deterioration. However, there is an important shortcoming to these approaches: countries with weaker administrative capacity—which are usually those most affected by food crises—are less likely to have implemented any TCTs or CCTs.Footnote 3 In this line, Delgado et al. (2010) argue that “it is essential that during noncrisis years, countries invest in strengthening existing programs—and piloting new ones—to address chronic poverty, achieve food security and human development goals, and be ready to respond to shocks.”

When TCTs and CCTs are not available, governments may implement other types of assistance programs. First, school feeding (SF) programs might be useful to relieve child malnourishment. However, they are usually ineffective to combat infant malnutrition (when adequate nutrition is most needed), unless food consumed at school can be complemented with take-home rations for younger siblings. Additionally, SF relies on geographic rather than household-specific targeting and entails food storage and distributions costs. Food for Work (FfW) programs are a second option. These are easier to implement and are (in principle) self-targeted: they provide low wages so only poor people should be interested in participating. However, in very poor regions, the vast amount of unemployed and underemployed may lead to considerable leakages and distortions in the labor market (Wodon and Zaman 2008). Also, only a portion of the funds allocated to these programs directly cuts poverty. Beneficiaries leave other jobs to participate in them; thus, the benefits of FfW are not the whole wages they provide, but only the differential income (with respect to the previous job). These programs might create distortions in the labor market. Finally, governments can also provide direct food aid. However, there is no guarantee that this aid can be effectively targeted toward the most vulnerable populations. Furthermore, food aid may become an entitlement and might result in long-term fiscal problems.

2.1.2 Price Stabilization Policies

Support programs for the poorest might not be easily implemented during food emergencies because they take time to be put into action. At the very least, they require a distribution network and plenty of logistical coordination. This forces governments to implement other policies to shield their population from food emergencies. Moreover, even when technically sound schemes such as CCTs are readily available during a crisis, some countries might still try to pursue more widespread measures for political reasons.Footnote 4 Constituencies (and, in general, populations) are very sensitive to food prices, and governments may fear opposition, turmoil, or even being ousted. For example, Burkina Faso suspended import taxes on four commodities after the country experienced riots over food prices in February 2008. Other countries that experienced riots during the 2007/08 crisis were Bangladesh, Cambodia, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Indonesia, Mauritania, Senegal, and Yemen (Demeke et al. 2008).

In this light, many countries try to stabilize prices through trade policies and management of food reserves. The specific trade-offs imposed by these mechanisms will be discussed subsequently. In general, they are not first-best options: countries use scarce resources to reduce general prices, effectively subsidizing both the poor and the nonpoorFootnote 5 and creating potentially pervasive market distortions. However, countries with no other means or with politically unstable regimes may have few other options to cope with food emergencies.

2.2 Medium- and Long-Term Policies

Short-term responses mainly deal with demand problems as consumers—and especially the poor—are hard-hit. However, short-term policies that help consumers might be detrimental for producers and for market development in the long run. For example, export taxes on wheat in Argentina help decrease consumer prices, but also disincentive production. As suggested by a newspaper article, “with scant incentive to produce, farmers have slashed the land sown with wheat to a 111-year low, and cereal exports from the rolling pampas of what should be a breadbasket country have virtually halved over the past 5 years. Wheat farmers in Argentina have turned to other crops, such as soybean, while some international investors, who are critical to the flow of money into capital-intensive agriculture, have left the country and turned to Uruguay, Paraguay, and Brazil”.Footnote 6 While acknowledging the importance of short-term responses to food crises, these responses should be chosen to minimize any long-term adverse effects on agricultural supply.

Long-term policies that expand food availability are becoming increasingly important.Footnote 7 Agricultural demand has experienced large expansions in recent years—even above that regularly imposed by population growth—due to rapidly growing incomes in developing countries (such as China and India) and rising demand of food for biofuel production in developed countries.Footnote 8 As these patterns are likely to persist, there is a need to increase agricultural supply in order to keep up with the additional demand.Footnote 9

There are two main policies targeted toward increasing food production. The rate of growth of the yields of major crops has been declining steadily since the 1970s. Thus, on the one hand, there is the need to enhance the productivity and resilience of major crops. Yet many challenges will make this a daunting task. Availability of fertile land will be limited by increasing urbanization, salinization, erosion, and degradation. Water will also become scarcer. Additionally, climate change will most certainly have an adverse effect on agricultural production through erratic rainfall, pest proliferation, and crop failure. Thus, any policy to increase agricultural productivity should address these complex obstacles.

On the other hand, supply can also be expanded through the enhancement of postharvest practices. Between harvest and consumers’ access to food, agricultural production goes through many stages: product processing, storage, handling, transportation, and distribution. In each of these phases, there are production losses. For example, grains molder with improper storage technologies and facilities, as well as poor roads, preventing food from reaching markets. Albeit complementary, even in the absence of productivity gains, better postharvest practices can have a significant impact on food availability.

3 Policies Recommended After 2008

3.1 Short-Term Policies

3.1.1 Trade Policies

When faced with increasing food prices, net food exporters can impose export taxes or bans. While lower prices hurt local producers, these policies do benefit domestic consumers and boost the revenue of governments enacting them. Thus, it is not surprising that many food-producing countries enacted some form of export restriction during the 2007/08 food crisis. Demeke et al. (2008) surveyed different government policies in 81 developing countries and found that 25 of them either banned exports completely or increased export taxes.

Analogously, net food importers can decrease their tariffs (or even subsidize imports) to buffer the impact of rising international food prices. At least in the short run, these policies are able to temporarily reduce internal prices; however, they also have domestic side effects (see Table 19.1). Some argue that tariff reductions might not have been effective in shielding importing countries from the 2007/08 food crisis. FAO et al. (2011) argue that “the scale of price increases was such that for many countries reducing import tariffs had relatively modest impact because the initial tariffs were low or the scale of the price increases was so large. In any event, this instrument was quickly exhausted as tariffs were reduced to zero” (p. 14). Additionally, tariff reductions diminish governments’ revenue, leaving them with fewer resources with which to palliate the impact of food price increases. The situation might be especially serious when there are few alternative sources of revenue (e.g., weak tax collection, large informal sector, etc.). Eventually, this could lead to serious fiscal deficits.

These strategies should not entail any consequences for international markets if only small countries implement them. These countries’ food exports or imports are not substantial relative to international trade, and they are mostly price takers on the world markets. However, trade policies of large food exporters or importers do effectively affect international supply or demand of a commodity. When large exporters impose export restrictions during a food emergency, they tighten the already short supply abroad and further increase international prices. In a similar fashion, as large food importers reduce their tariffs, they increase internal consumption, fueling global demand and generating further escalations of food prices in external markets. If exporting and importing countries both follow these strategies, their efforts to insulate themselves might cancel out each other’s efforts.

Martin and Anderson (2011) describe this phenomenon on the international market for a certain commodity. Initially, there is excess supply from world’s exporters and excess demand from importers. The authors then consider an exogenous shock that reduces production in some exporting countries. In the absence of any trade policy, this shock changes the balance between supply and demand. If a large exporting country tries to avoid an increase in domestic prices and imposes a tax on exports, this further reduces the excess supply and leads to higher international prices. If a large importing country retaliates and reduces its tariffs to exactly offset the trade policy imposed by the large exporter, this would increase global excess demand. The final outcome in this scenario is that the traded quantity and price in both countries would be the same as before either policy was enacted. However, other countries around the world would be worse off, as the final price on the international market would soar. This can eventually give other countries the incentive to impose similar policies, leading to a trade war of import tariffs and export taxes. As Martin and Anderson (2011) suggest, “insulation generates a classic collective-action problem akin to when a crowd stands up in a stadium: no one gets a better view by standing, but any that remain seated gets a worse view.”

So to what extent should countries implement such policies and impose beggar-thy-neighbor consequences upon others? There is no consensus in this respect. On one hand, Timmer (2010) analyzes the implications of trade restrictions on rice markets during the 2007/08 food crisis and finds that stabilizing domestic prices using domestic border intervention could be an effective strategy to handle food crises. Timmer argues that unstable demand and supply needs to be accommodated somehow, and that passing this responsibility to the international market may be the most fair and successful way to do so.

On the other hand, Anderson and Nelgen (2012) advise against any trade restrictions, using a model of supply and demand for the market of a particular commodity. Their results are presented in Tables 19.2 and 19.3. Table 19.2, not surprisingly, shows that trade restrictions did boost international food price increases between 2006 and 2008.Footnote 10 Yet the results also suggest that everyone should take part of the blame for this: the policies of both exporting and importing countries, and both developing and high-income countries, fueled the price increases. Table 19.3 compares the changes in international prices that would have taken place without trade interventions with effective domestic prices. All in all, their estimates show that these policies had a very heterogeneous impact for different countries and commodities. On average for all countries, domestic wheat prices increased more than adjusted international prices. These policies were somewhat more effective for other crops, but overall their effect was not large: 2 % for maize and 12 % for rice.

Anderson and Nelgen (2012) advise governments to refrain from imposing insulating trade policies because they amplify price increases and, moreover, are not always effective. Theoretically, small countries cannot affect international markets individually by changing their trade policies. However, Anderson and Nelgen (2012) claim that if many small countries do so simultaneously, it can have an aggregate sizeable impact. In this line, they argue that trade restrictions and reduction of import tariffs should be discouraged across the board.

To analyze this last point, Table 19.4 shows the shares of imports and exports for soybean, rice, wheat, and maize by region (following the World Bank classification)Footnote 11 in 2004, before the food crisis. We posit that Anderson and Nelgen’s results (in Tables 19.2 and 19.3) seem to hide very large disparities within their “exporting,” “importing,” “developing,” and “high-income” labels. For example, estimates in Table 19.2 show the impact of trade restrictions on the increase of the international price of rice to be around 40 %; 38 % is from developing (with the remaining 2 % from high-income countries) and 18 % is from importing countries (and the remaining 22 % from exporting countries). From the export side, Thailand, India, and Vietnam—which account for 65 % of all rice exports—imposed trade restrictions. From the import side, important importers such as the Philippines and other Asian countries were concerned about a potential shortage and reduced their tariffs. Policies enacted by these large players exemplify how trade restrictions can lead to significant price spikes. However, from the evidence presented in Tables 19.2 and 19.3, it is unclear if trade restrictions by smaller countries would entail serious consequences for international markets. For example, Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for 0.1 % of rice exports worldwide. Excluding Nigeria, South Africa, Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana, the share of all other Sub-Saharan African countries was only 10.7 % of worldwide rice imports. It is reasonable to believe that, even if all nations in this region changed their trade policies, there would not be a sizable impact on the international rice market.

While economists tend to be more critical of the use of import barriers as creating instability in world markets, they frequently applaud import barrier reductions undertaken in the same context. There may be some basis for this support if the reduction is believed to be permanent once undertaken. If, however, it is undertaken purely on a temporary basis as a way to reduce the instability of domestic prices, the effects on the instability of world prices are clearly quite symmetric. From a policy viewpoint, this remains an important distinction because the multilateral trading system has quite different rules in the two cases (see Bouët and Laborde 2010).

In addition, any of these policies may have important beggar-thy-neighbor consequences and may fuel price increases of important commodities. Insulating trade policies imposed by importers and exporters (as well as high-income and developing countries) were indeed responsible for a considerable share of price spikes seen during the 2007/08 food crisis. However, most of the turmoil was likely caused by large exporters and importers. In this sense, policy recommendations should distinguish between larger and smaller countries.

Finally, there is a key asymmetry between net exporters and net importers of an agricultural commodity during a food crisis. Net exporters can benefit from increases in world prices, but net importers are hurt and have no capacity to retaliate efficiently. If large exporting and importing countries cooperate, then it is possible for smaller countries to implement policies to reduce import tariffs and, in the short term, reduce national prices. Clearly, however, any non-cooperation by large importing countries implementing similar policies will neutralize this effect.

3.1.2 Food Reserves

Food reserves can be maintained in order to service emergency relief operations, support public distribution of food to chronically food insecure shares of a country’s population, and reduce volatility in consumer and/or producer prices, thus stabilizing prices. The basic idea is simple: accumulate food stocks when prices are low (to prevent very low prices that would harm producers) and release them when supply becomes tighter (to reduce very high prices that harm consumers). However, international experience in the management and use of reserves is not clear and is open to significant variation in policies under the Global Food Crises Response Program (GFRP) operations because the so-called strategic grain reserves were not clearly defined.

Timmer (2010) advises governments to hold rice buffer stocks to reduce volatility in the domestic market. Rather than requiring governments to cope with the consequences of food crises, reserves would ensure price stability and prevent acute crises from taking place. However, Timmer’s recommendations should be taken with caution, as his analysis is very specific to the rice market, which is much more speculative than other markets.

Gouel and Jean (2012) argue that buffer stocks do not provide relief when there are sharp increases in international food prices. Using a theoretical model for a small open economy, the authors find that buffer stocks might help producers by keeping prices from reaching low levels. However, such stocks do not protect consumers from price spikes without further trade restrictions; this is because small economies are price takers, so domestic prices will follow the international markets (adjusted by transport costs). When prices are high on the international market and there are no export restrictions in place, at least part of the reserves accumulated in buffer stocks will be exported, given that there is no need for local distribution, and will maximize the returns to the commodities being held, which need to rotate to minimize operation costs. While these policies may increase governments’ revenues (exporting their stocks when international prices are high), they do not protect consumers from high commodity prices.

Domestic buffer stocks posit other problems. First, as they aim to control general prices, they are less effectively targeted toward the neediest shares of a country’s population (Wright 2009). Second, storage can be expensive, and the poorest countries (which are most vulnerable to food crises) are the ones least likely to be able to afford expensive storage costs (Torero 2011). Third, poor management renders buffer stocks ineffective in many cases. When controlled by parastatals and other government agencies without strong accountability systems, they are potentially subject to political use and mismanagement. Finally, buffer stocks create market distortions; as perishable reserves have to be rotated, their cyclical interventions in the market can send wrong signals to producers and consumers.

For most of these authors, national emergency reserves seem to be a better option than domestic buffer stocks for price stabilization. While buffer stocks for price intervention require considerable stockpiling and subsidize both the poor and the nonpoor, emergency food reserves can more effectively provide aid to the most vulnerable shares of a country’s population and entail smaller costs because they require smaller reserves (see Wright 2009). Also, reserves are less likely to create market distortions and disrupt private sector activities (FAO et al. 2011). These mechanisms might prove especially useful for isolated or landlocked countries where, in case of distress, sluggish transportation of food assistance can pose serious threats to vulnerable shares of the population.

The extreme volatility observed during the 2007/08 food crisis suggests that some mechanism of food reserves for price stabilization is necessary to ease the effect of shocks during periods of commodity price spikes and high volatility. (For further discussion of such mechanisms, see Chap. 6 of this book.) There seems to be some consensus around this idea, but policymakers disagree about which specific mechanisms to use to implement such food reserves. As in the case of trade interventions, the most appropriate choices are likely to depend on the characteristics of the specific market under intervention, each country’s capacity to cope with crises, and the possibility of establishing international coordination mechanisms. While it likely does not make sense to establish national buffer stocks in most grain markets, Timmer’s (2010) support for them may be more valid in a few cases. For example, rice markets might be more speculative than others; thus, price stabilization through buffer stocks makes somewhat more sense in this case. On the other hand, buffer stocks usually entail high costs and market distortions and are prone to corruption. Thus, most countries—especially those with weak institutions and scarce resources—should probably refrain from using stocks and should instead establish emergency reserves for humanitarian reasons.

3.2 Medium- and Long-Term Policies

In this section, we summarize the major medium- and long-term policies proposed.

3.2.1 Policies to Increase Agricultural Productivity and Resilience

There is a wide array of policies aimed at increasing agricultural productivity and resilience; some of the most widely discussed include:

3.2.1.1 Input Subsidies

The World Bank (2008) argues that “while development of efficient agricultural input market is a long-term process, this subcomponent (improving smallholder access to seed and fertilizer) would provide rapid support to clients facing immediate and near-term constraints related to seed and fertilizer availability, distribution, affordability and utilization” (p. 90). The plan envisages the implementation of a market-smart approach, characterized by: (a) targeting poor farmers; (b) not displacing existing commercial sales; (c) utilizing vouchers, matching grants, or other instruments to strengthen private distribution systems; and (d) being introduced for limited periods of time only.

While they provide a sensible rationale, it is unclear how these principles would be implemented in practice. Poorer countries—which likely have the least developed input markets—may find it difficult to target only those farmers in need. Additionally, subsidy programs that would strengthen, rather than displace, the private sector are likely to require complex mechanisms; institutional weaknesses in poor countries may render these programs unfeasible.

Moreover, these programs usually entail significant fiscal costs. Zaman et al. (2008) estimate that Malawi’s input subsidy program costs approximately 3 % of GDP. Importantly, in recent years, rising fuel prices have considerably increased fertilizer costs. If this trend continues in the future, the budget implications of these policies would become even larger.

Finally, more evidence is required to assess the effectiveness of these policies. Dorward et al. (2010) evaluate the 2005/06–2008/09 fertilizer subsidy program in Malawi; their estimates of the benefit–cost ratios of the program range from 0.76 to 1.36, with a (rather small) mid-estimate of 1.06. Arguably, with recent increases in fertilizer prices, a current benefit–cost ratio of the program may be even smaller. Additional potentially adverse impacts of the displacement of private sector operations still require more thorough evaluation and understanding.

3.2.1.2 Investment in Research and Development

The introduction of high-yield varieties was instrumental for increases in agricultural supply during the 1960s and 1970s. The foreseeable worsening of climatic conditions imposes new challenges, however. Currently, new strands of wheat, maize, rice, and other crops are being developed to have enhanced resistance to droughts, diseases and insects, salinity and other soil problems, extreme temperatures, and floods. In addition, other developments promise enriched varieties with higher nutritional content.

Such policies are highly profitable. Byerlee et al. (2008) find that “many international and national investments in R&D have paid off handsomely, with an average internal rate of return of 43 % in 700 R&D projects evaluated in developing countries in all regions” (p. 11). However, research and development (R&D) is a typical public good and, as such, faces considerable underinvestment, particularly in developing countries. Thus, governments must expand their expenditures in R&D and must complement this budget increase with other policies. For example, the sustainability of these programs requires private–public participation in the seed industry to generate demand and supply coordination. It also requires strengthening regulatory policies in seed markets, including variety release, seed certification, and phytosanitary measures. R&D should also envisage extension services and other mechanisms to facilitate diffusion and technology adoption by farmers.

3.2.1.3 Irrigation

Investment in irrigation should be a critical component of any strategy to increase agricultural supply. Irrigation more than doubles the yields of rain-fed areas because more crops can be harvested in any given year; it also at least partially promotes resilience, protecting farmers against droughts. Delgado et al. (2010) estimate that expansion of irrigation infrastructure to all land in developing countries “would contribute about half of the total value of needed food supply by 2050.”Footnote 12

Irrigation projects appear to exhibit high rates of return. Jones (1995) analyzes 208 World Bank-funded irrigation projects and finds an average rate of return of 15 %. Despite the importance and impact of such projects, the Global Food Crises Response Program (GFRP) has determined that “under this emergency response program, it is not anticipated that investment support would be provided for new irrigation schemes, as this would be supported under the Bank’s regular lending program.”Footnote 13

3.2.2 Policies to Reduce Postharvest Losses

Developing countries face significant postharvest losses due to mishandling. For cereals, these are estimated to be 10–15 % of harvest; when combined with deterioration in storage (in farms and facilities) and milling, this number can reach 25 %. Poor (or nonexistent) roads compound these losses, as agricultural products cannot reach consumer markets, and information failures impede supply from reaching demand (or at least prevent it from reaching the most efficient markets). Some of the policies discussed to reduce postharvest wastage include:

3.2.2.1 Improved Handling of Harvests and Storage Practices

Significant portions of agricultural production are lost due to postharvest mishandling. One example comes from improper drying of crops. If crops are stored in high humidity, they can be affected by mycotoxins and become unfit for consumption. In addition to the risk of growing mold, production stored in improper containers can also attract plagues, insects, and rodents, which can spoil the food. This is only one example of postharvest mishandling in a process where any number of small practices can potentially spoil food. Training in proper drying techniques and building adequate infrastructure in this area can considerably reduce wastage and improve food availability.

The implementation of extension services for postharvest losses should include: (1) training and demonstration of low cost-on-farm storage; (2) technical assistance and investment support for community-level food banks; and (3) training and investment support for grain traders and millers in drying and sorting, as well as fumigation equipment and upgrades in existing storage facilities. These should be complemented with strengthening inspections and quality control surveillance to prevent the spread of pests or diseases.

3.2.2.2 Information Systems

Imperfect information is especially pervasive in agricultural markets at both the domestic and the international levels. In both cases, a lack of adequate and timely information creates a mismatch between supply and demand. In many cases, the consequence is the allocation of production to suboptimal markets, where the demand is lower. In other cases, severe information constraints can result in agricultural production not reaching any market at all and thus being wasted.

At the domestic level, many countries have implemented agricultural information systems that can be accessed through internet portals, SMS on mobile phones, kiosks, radio shows, etc. The challenge ahead is to find cost-effective mechanisms to produce timely information that can be easily and widely accessed by producers and traders.

At the international level, there is scarce reliable data on stocks and availability of grains and oilseeds. Additionally, there is little monitoring of the state of crops and short-term forecasts based on trustworthy technology (remote sensing, meteorological information, etc.). FAO et al. (2011) proposed the creation of the Agricultural Market Information System (AMIS), which involves major agricultural exporters and importers, as well as international organizations with expertise in food policy. It comprises two organisms: the Global Food Market Information Group (to collect and analyze food market information) and the Rapid Response Forum (to promote international coordination). While the specific details of its duties and membership (and the political negotiations surrounding them) still need to be addressed, AMIS is a first step in answering the need for global information and coordination mechanisms.

3.2.2.3 Rural Roads

Transport infrastructure plays an important role in the reduction of both the level and variability of food prices. Without roads to transport their agricultural production, some farmers cannot reach consumer markets; others have market access, but at a very high cost. Delgado et al. (2010) argue that, in most cases, transport costs represent 50–60 % of total marketing costs. Byerlee et al. (2008) estimate that less than 50 % of the rural African population lives close to an all-season road. Transport infrastructure can also help reduce price variability. Roads are useful means to spread out regional shocks; if a certain region is hit by a shock (weather or other), it can import food from another region. For example, during the food crisis, regions with better infrastructure in Indonesia were not hit as hard as those poorly connected.

4 Analysis of Consistency

The question that this section tries to answer is how consistent or inconsistent the operational policy recommendations have been with respect to: (a) Proposals of International Organizations and the G8’s document prepared for the Ministers of Finance Meeting in 2008 and (b) the different policy recommendations proposed by key researchers and analyzed in detail in the previous two sections. With this objective in mind, we analyze as an experiment the portfolio of loans of GFRP operations detailed in Table 19.5, covering operations in 13 developing countries. Table 19.6 provides a detailed summary of all these World Bank operations which have as their core objective the mitigation of the impact of the food crisis.

Following an assessment of each of the specific operations for the 13 developing countries, benefits are analyzed and summarized in Table 19.7:

-

(a)

Mozambique: Overall, consistent with the policy recommendations in 2007/08 and after 2008. The government allowed a pass-through of international prices while protecting vulnerable groups (expanding PSA program). In addition, through the GFRP operation, the World Bank supported the implementation of reforms to increase agricultural productivity through the provision of infrastructure and public goods (technology adoption, construction of silos, agricultural infrastructure, etc.).

-

(b)

Bangladesh: Overall, consistent with the policy recommendations on trade in 2007/08 but not consistent with later World Bank research after 2008. Specifically, the GFRP operation was used in accordance with the GFRP framework to support the reduction of import duties for rice and wheat, and there was an increase of public food stocks (at least partially to act as price buffers) from 1 to 1.5 million tons. On the other hand, it is important to mention that the increased public targeting for aid programs was positive in terms of performance of the program in identifying the proper beneficiaries. However, most of it was untargeted and had severe leakages (e.g., large share of budget allocated to open market sales).

-

(c)

Philippines: The GFRP operation resulted in a combination of policies which were consistent with the official World Bank policy recommendations in 2007/08 and were both consistent and inconsistent with the post-2008 recommendations. On the consistent side, as a result of the GFRP operation, the government launched the Household Targeting System for Poverty Reduction (NHTS-PR) and introduced a CCT (Pantawid Pamilya). In addition, the NHTS-PR will become a targeting instrument for other social programs, and the Food for School Program is prioritizing the poorest provinces and municipalities to enhance targeting of the most vulnerable share of the population. Finally, the government pushed for a regional rice reserve mechanism through ASEAN, which is an emergency regional rice reserve to assure food security in the region and which has a very clear trigger mechanism and governance. In addition, the country was engaged in large rice import tenders, exacerbating increases in international food prices, but the GFRP made the government commit, as part of the loan, to change its tendering policy in a way that would reduce prices. The government also agreed to withdraw a big tender that was going to increase price pressure in the international market. Finally, bilateral rice deals were established, reducing pressure on external markets. These policies, although consistent in the short term with the GFRP framework, are inconsistent with later World Bank recommendations. In the medium term, the government is due to lift quantitative trade restrictions by WTO agreements, and there is a medium-term plan to transfer rice trade to the private sector. However, currently the National Food Authority (NFA) has the monopoly over rice imports. NFA still concentrates a significant proportion of its food aid budget, which is poorly targeted. NFA’s reserves act as a buffer stock for price stabilization.

-

(d)

Djibouti: The GFRP operation resulted in a combination of policies which were consistent in general with the official World Bank policy but which, at the same time, were inconsistent with the policy recommendations after 2008. On the consistent side, when the crisis started, there were few social protection mechanisms; the government was able to expand the WFP-operated food assistance program in rural areas (one of the few existing) with GFRP support. It also completed a population census as a first step to implement direct and targeted protection mechanisms for the poor and provided support for fisheries to boost food production. On the inconsistent side with the post-2008 recommendations but consistent with the GFRP framework and official policy of the World Bank, the government eliminated the consumption tax rates on five basic staples; this policy was not effective in reducing consumer food prices. Low pass-through rates were probably due to high concentration in the food market (few importers and distributors) and security risks posed by pirates in international waters.

-

(e)

Honduras: Overall, consistent with the policy recommendations. The proposed operation seems to be more oriented to releasing funds for the government to aid the financial sector, given the government is concerned about the effect of increasing food prices on households’ real income; therefore, the government uses the resources as a buffer to mitigate the expected adverse effect on banks’ outstanding portfolio of consumer loans. However, the financial sector was not the real target of the operation; it was just the fastest way to transfer cash to the government for more general crisis response policies.

-

(f)

Haiti: The GFRP operation resulted in a combination of policies which were both consistent and inconsistent with the policy recommendations. On the consistent side, as a result of the GFRP, a “Program of Action against the High Cost of Living” (with a focus on employment generation through labor-intensive works and expansion of food assistance programs) was developed. In addition, the government also implemented what they refer to in the GFRP framework as a second best policy, i.e., subsidies to reduce the price of rice between May and December 2008 (US$30 million). However, there are specific circumstances that need to be met for the Bank to accept this type of policy (see GFRP Framework document p.26, para. B2). Moreover, post-2008 these policies were not supported.

-

(g)

Cambodia: The GFRP operation resulted in a combination of policies which were consistent with the GFRP framework and official position of the World Bank. Despite the initial ban on rice exports in March 2008, they lifted this ban in May 2008 and are currently seeking to promote rice production. The main policy is to create price incentives by promoting exports (goal of one million tons of milled rice exported by 2015). In addition, they expanded the “Identification of Poor Households Targeting Program” to be applied to safety nets, implemented food for cash and food for work programs, and boosted credit for milling facilities which act as an interface between smallholders and markets. In addition, consistent with the GFRP framework and official World Bank position in 2008, the GFRP operation subsidized fertilizers by the suspension of the VAT and by implementing a pilot for “smart subsidies” using vouchers to be distributed to smallholders. However, this type of policy was not recommended post-2008, given (as it has been shown in the case of Malawi) that it bears the risk of significant fiscal deficit. Finally, the government regulated the fertilizer market in principle to avoid adulteration; however, most of the adulteration appears to happen in Vietnam (from where fertilizer is imported) rather than in Cambodia.

-

(h)

Mali: The GFRP operation resulted in policies which were both consistent and inconsistent with the official policy recommendations of the World Bank and with what was recommended after 2008. On the consistent side, the government increased seed availability for locally produced rice varieties and improved marketing channels to facilitate relationships between producer organizations. Finally, a program of subsidies for equipment, access to water/irrigation, and extension services was implemented. On the inconsistent side, the government introduced 6 month VAT and tariff exemptions for rice, implemented a price-stabilizing buffer stock through the Food Security Commission, introduced subsidies on crop inputs which were not “smart subsidies,” and finally, despite acknowledgement of weak safety nets, made no efforts to strengthen them.

-

(i)

Guinea: The GFRP operation resulted in a combination of policies which were both consistent and inconsistent with the official World Bank policy recommendations and with the post-2008 recommendations. On the consistent side, in both policies recommended in 2008 and after 2008, the government implemented a safety net system to distribute take-home rations for children of families of 5+ members, an emergency school feeding and nutrition support, and an emergency urban labor-intensive public works program. On the inconsistent side, the country imposed a ban on agricultural exports in 2007; although it was lifted in 2008 for most products, it was not lifted for rice. Although the GFRP operation did not support this, the government could have included a conditionality to be able to obtain the loan. In addition, and consistent with the GRFP framework but not the post-2008 recommendations, with support from the GFRP, the country was able to eliminate custom duties for low quality rice between June 1 and October 31, 2008, and initiated plans to build an emergency food reserve of 25,000 metric tons, although it is not clear if this is for humanitarian or price-stabilizing purposes. Finally, the government implemented the “Emergency Agricultural Productivity Support,” which includes the distribution of subsidized seed and fertilizer packages to 70,000 smallholder farmers, although these were not the type of smart subsidies proposed by the GRFP framework.

-

(j)

Burundi: The GFRP operation resulted in a combination of policies which were both consistent and inconsistent with the official World Bank policy recommendations. On the consistent side, the government scaled up WFP’s school feeding and nutrition program. However, funds allocation and the number of beneficiaries fell short of initial goals. In addition, the government supported the return of refugees to the country. Finally, and consistent with the GRFP framework but inconsistent with post-2008 recommendations, the government implemented exemption of transaction taxes and import duties until July 2009.

-

(k)

Madagascar: The GFRP operation resulted in a combination of policies which were consistent with the official World Bank policy recommendations. The government expanded the food for work and school feeding programs and introduced a rice intensification campaign through producer associations. This program aims to provide subsidies for selected agricultural technologies through microfinance institutions. Finally, the government eliminated the VAT for rice, which, although consistent with the GFRP framework, was not consistent with post-2008 recommendations.

-

(l)

Sierra Leone: The GFRP operation resulted in a combination of policies which were both consistent and inconsistent with the official World Bank policy recommendations. On the consistent side, the government protected selected basic services from increasing costs of food and fuel (those for hospital patients, lactating mothers, government’s boarding schools, etc.). In addition, the tariffs for four products were reduced; this reduction is to be maintained until prices return to precrisis levels. On the inconsistent side, the government provided fully subsidized rice seed to farmers (71,000 bushes), which were not targeted as the “smart subsidies” strategy recommended in the GFRP.

-

(m)

Rwanda: The GFRP operation resulted in policies which were inconsistent with both the official World Bank policy recommendations and the post-2008 recommendations. Specifically, the government implemented the Crop Intensification Program for food crops which included significant market intervention by the government: (a) purchasing fertilizers in bulk in international markets; (b) auctioning fertilizer to private traders; (c) promoting private microcredit for smallholders; and (d) providing additional targeted subsidies through vouchers. This program has significant risks: mis-targeting, crop leakage (i.e., cannot be used for export crops), collusion among traders, and an extremely low loan recovery rate (during a pilot in 2008, recovery was only 4 %).

5 Final Remarks

The world faces a new food economy that likely involves both higher and more volatile food prices, and evidence of both conditions was clear in 2007/08 and 2011. After the food price crisis of 2007/08, food prices started rising again in June 2010, with international prices of maize and wheat roughly doubling by May 2011. This situation imposes several challenges. In the short run, the global food supply is relatively inelastic, leading to shortages and amplifying the impact of any shock. The poor are hit the hardest. In the long run, the goal should be to achieve food security. The drivers that have increased food demand in the last few years are likely to persist (and even expand). Thus, there is a significant role for the World Bank to play in increasing the countries’ capacity to cope with this new world scenario and in promoting appropriate policies that will help to minimize the adverse effects of the increase in prices and price volatility, as well as to avoid exacerbating the crisis.

In this regard, this chapter describes some of the most important official policies that the World Bank prescribed to different countries during the food crisis of 2007/08. In addition, it compares those policies to what was proposed by World Bank research after 2008. The chapter focuses on the proposed short-term, medium, and long-term policies. In terms of short-term policies, two mechanisms are emphasized: support for the poor and price stabilization (with an emphasis on trade restrictions and food reserves). In terms of medium- and long-term policies, we focus on the recommendations linked to increasing agricultural productivity through productivity gains and elimination of postharvest losses.

In support of the poor, Targeted Cash Transfers (TCT) and Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) programs already in place clearly constitute first-best responses for several reasons: (a) they prioritize assistance for targeted groups, (b) they do not entail additional costs of food storage and transportation, (c) they do not distort food markets, and (d) in the case of CCTs, they explicitly prevent human capital deterioration. When TCTs and CCTs are not available, governments may also implement other types of assistance programs, although this could bring some inefficiency. Therefore, in poor countries where TCTs and CCTs are not yet in place (such as most Sub-Saharan Africa), it is essential that during noncrisis years, countries invest in strengthening existing programs—and piloting new ones—to address chronic poverty, achieve food security and human development goals, and be ready to respond to shocks. Across the different GFRPs, we see these policies implemented by the World Bank, specifically in the Philippines, Djibouti, Haiti, Cambodia, Guinea, Burundi, and Madagascar.

In terms of short-term price stabilization policies through trade policies and management of food reserves, we identify important inconsistencies in what was recommended in the official position by the World Bank, through the GFRP framework document and in the G8’s document prepared for the Ministers of Finance Meeting in 2008, and in post-2008 recommendations. Clearly, the official recommendations in 2008 were more flexible, especially in regards to trade policies and physical reserves, and in some cases allowed short-term interventions that could end in pervasive market distortions. As a result, most of the operations under the GFRPs were consistent with the official policy recommendations with the exception of Cambodia, Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Rwanda (see summary in Table 19.7).

On the other hand, if we look at the post-2008 recommendations, all of them will avoid any potentially pervasive market distortions. Even more, regarding trade policies, most of the work of the World Bank will advise against any trade restrictions (on both the import and the export side). In that sense, if we assess ex post the GFRP operations, we find that in many of the countries, the policies implemented as a result of the GFRP created additional trade restrictions other than export bans, which was the only bad policy identified in the GFRP framework document. This was the case for Bangladesh, Philippines, Mali, Guinea, Burundi, and Sierra Leone.

Nevertheless, and as explained in Sect. 19.3, it is important to mention that what the GFRP framework recommended in 2008 relative to what was recommended post-2008 is in a certain way justifiable as a short-term measure given that all in all, trade policies may be an effective instrument for short-term price stabilization purposes in some nations: those facing considerable political unrest, lacking adequate food distribution networks, with no safety nets available, etc. However, they may have important beggar-thy-neighbor consequences and may fuel price increases of important commodities. The 2007/08 food crisis—especially in the case of rice—is quite illustrative in this respect. Insulating trade policies imposed by importers and exporters (as well as high-income and developing countries) were indeed responsible for a considerable share of price spikes. However, even when the aggregate effect of the actions of these broad groups is quite large, most of the turmoil was likely caused by large exporters and importers. In this sense, if the argument is that such policies create further imbalances for others, policy recommendations should distinguish between larger and smaller countries; from all the countries where we see these inconsistencies, the Philippines is the only one falling into the category of a significant importer of rice where the World Bank should be clearly against import tenders and quantitative restrictions, given they clearly helped to exacerbate international prices in the rice market.

With respect to food reserves, the discussion seems to highlight the need for food reserves to ease the effect of shocks during periods of commodity price spikes and volatility. There seems to be some consensus around this idea. The disagreement stems from the specific mechanisms to implement food reserves. As in the case of trade interventions, the most appropriate choices are likely to depend on the characteristics of the specific market under intervention, the country’s capacity to cope with crises, and the possibility of establishing international coordination mechanisms. While it likely does not make sense to establish national buffer stocks in most grain markets, it may be more valid in a few cases, such as in the rice market. Again, however, regional reserves with strong governance and clear triggers are preferred. However, it is important to mention that the GFRP framework is not extremely clear on this in difference to what was recommended post-2008. It is in that sense that when analyzing the operational plans of the GFRPs, proposals can be identified that promote country-level reserves as buffer stocks, as in the case of: (a) Bangladesh where the stocks were increased from 1 to 1.5 million MT of rice, (b) the NFAs in Philippines, and (c) the NFAs in Guinea. It could also be argued that these reserves were consistent with the official position of the World Bank through the GFRP framework, although clearly these types of policies are problematic in countries where the necessary conditions for these reserves to work don’t exist. Additionally, buffer stocks usually entail high costs and market distortions and are prone to corruption. Thus, most countries—especially those with weak institutions and scarce resources—should probably refrain from using buffer stocks.

Finally, with respect to the medium- and long-term policies, we see significant investment in the GFRPs (e.g., the provision of infrastructure and public goods in Mozambique, increasing seed availability in Mali, and the rice intensification program in Madagascar). In addition, and as recommended in the GFRP framework document, we also see the important presence of input subsidies similar to those that have failed in Malawi with a fiscal cost of around 3 % of the GDP. These plans envisage the implementation of a market-smart approach to input subsidies. Such a strategy is characterized by: (a) targeting poor farmers; (b) not displacing existing commercial sales; (c) utilizing vouchers, matching grants, or other instruments to strengthen private distribution systems; and (d) being introduced for a limited period of time only. Albeit outlining a sensible rationale, it is unclear how these principles would be implemented in practice in poor countries like in the GFRPs in Haiti, Cambodia, Mali, Sierra Leone, and Rwanda. Poorer countries—which likely have the least developed input markets—may find it difficult to target only those farmers in need. Additionally, subsidy programs that would strengthen, rather than displace, the private sector are likely to require complex mechanisms. Institutional weaknesses of poor countries may render them unfeasible, aside from the fiscal costs.

It is important to note that in many countries, input markets are not well developed, as they are hampered by various policy, institutional, and infrastructure constraints that can only be overcome over time, while improvement in access to inputs would provide substantial benefits in the short run, given the crisis circumstances. It is in that sense that the “smart subsidies” proposed under the GFRP framework could be conceptually justifiable even though as a short-term measure they can also create fiscal problems as previously mentioned based on the Malawi experience. Moreover, it is of central importance that any “smart subsidy” policy includes the five key characteristics mentioned in the previous paragraph. Furthermore, a long-time horizon is required to apply the “first-best” policies, namely, the alleviation of constraints (such as infrastructure and missing credit markets) which inhibit the development of efficient input markets.

Therefore, although this “second best measure” in the face of existing constraints as stated in the GFRP framework document could be justifiable in the short term the key is to assure all other needed elements are in place for its success; specifically, it has to be guaranteed that investments to alleviate the key constraints of the input market are also started at the same time. All of these arguments are conceptually valid, although their applicability in any given country cannot be taken for granted; in most cases, applicability was not actually and explicitly verified in the assistance programs funded under GFRP, and the key four characteristics of the proposed “smart subsidies” strategies were not validated in advance.

In summary, when assessing the consistency of the specific loans and policies prescribed officially by the World Bank for selected countries during the 2007/08 food crisis, we identify that (given the significant flexibility of the World Bank official recommendations) most of the loans comply with what was proposed in the GFRP framework. However, when analyzing the consistency of those recommendations to the research results published by the World Bank post-2008, we found significant inconsistencies, especially in short-term policies. As a result, it is extremely important for the World Bank to carefully assess the risks and costs of the implementation of the official, more flexible, recommendations of the GFRP against what is currently being advocated at the Bank and to carefully assess how to avoid these inconsistencies in the future.

Notes

- 1.

There is a general concern that increasing food prices has especially adverse effects on the poor. However, until recently, there was no rigorous evidence of this. On the one hand, there would most probably be negative effects on poor urban consumers who spend a considerable portion of their budget on food. But on the other, there are gains to farmers who benefit from increased prices for their output. In general, this impact depends on whether the gains to net agricultural producers are larger than the losses to consumers. Directly dealing with this issue, Ivanic and Martin (2008) and Ivanic et al. (2011) find that the food crisis has led to significant increases in poverty rates in developing countries.

- 2.

Food security is a situation in which “all people at all times have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs, and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (World Food Summit 1996). Even when increases in food production are not a sufficient condition for food security, they are indeed a necessary condition thereof (von Braun et al 1992).

- 3.

For example, these policies might be more suitable for medium-income countries, such as in Latin America. World Bank—LAC (2008, Table 8) documents 17 countries with CCTs and 18 countries with Targeted Nutritional or Social Assistance Programs.

- 4.

As suggested by HDN and PREM (2008), “effective nutritional and social protection interventions can protect the most vulnerable from the devastating consequences of nutritional deprivation, asset depletion and reductions in education and health spending. Policy responses need to balance political economy considerations that call for measures to help a broad swath of the affected population, with the urgency of protecting the very poor.”

- 5.

Wodon and Zaman (2008) posit the following argument: “Consider the share of rice consumption in the bottom 40% of the population. This share varies from 11% in Mali to 32% in Sierra Leone. This means that if one considers the bottom 40% as the poor, out of every dollar spent by a government for reducing indirect taxes on rice, and assuming that the indirect tax cuts result in a proportionate reduction in consumer prices, only about 20 cents will benefit the poor on average.”

- 6.

“Argentina’s farmers unable to fill the wheat gap,” Financial Times, August 10th, 2007. Link: http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/910f25ac-a4a8-11df-8c9f-00144feabdc0.html\#axzz1vXMMOjP5

- 7.

Examples of other policies in the long run are: production and price insurance for farmers; provision of other public goods for rural areas (such as education and health services); policies for water basin management; technology improvements for rainfed land (water capture infrastructure, practices for water retention in soil, etc.); strengthening of producer organizations; etc. Certainly, these are also important policies. However, for the sake of brevity, they are not mentioned here.

- 8.

Mitchell (2008) estimates that about 70–75 % of food price increases were due to rising food demand for biofuel production.

- 9.

As suggested by the World Bank’s South Asia Region report (2010), “the food crisis is by no means over… There is growing agreement that a two-track approach is required, combining investments in safety nets with measures to stimulate broad-based agricultural productivity growth, with major emphasis on major food staples.”

- 10.

Their findings are qualitatively consistent with those of Bouët and Laborde (2010). Their calculations are based on a multicountry general equilibrium model for wheat. They show how price increases are amplified by both tariffs and export taxes.

- 11.

- 12.

This would require, however, 40 % more withdrawals of water for agriculture. Thus, these policies should be complemented by increased productivity in existing irrigated areas.

- 13.

GFRP would limit their financing to: (i) support quick turnaround physical investments in rehabilitation of existing irrigation (small-scale) schemes; (ii) finance investments in rehabilitation or development of field drainage and collector drains to reduce problems of water logging and soil salinity; (iii) finance training for water-user groups and others on operation and maintenance of investments; (iv) finance assessments of groundwater or surface water hydrology and sustainable water use; and (v) finance feasibility studies for medium-term irrigation investments.

References

Anderson K, Nelgen S (2012) Agricultural trade distortions during the global financial crisis. Oxf Rev Econ Policy 28(1):1–26

Bouët A, Laborde D (2010) Economics of export taxation in a context of food crisis: a theoretical and CGE approach contribution. IFPRI discussion paper 00994. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Byerlee D, de Janvry A, Townsend R, Savanti P (2008) A window of opportunities for poor farmers: investing for long-term food supply. Dev Outreach 10(3):9–12, The World Bank, Washington, DC

Delgado C, Townsend R, Ceccacci I, Tanimichi Hoberg Y, Bora S, Martin W, Mitchell D, Larson D, Anderson K, Zaman H (2010) Mimeo. Available at http://www.g24.org/TGM/fsec.pdf. The World Bank, Washington, DC

Demeke M, Pangrazio G, Maetz M (2008) Country responses to the food crisis: nature and preliminary implications of the policies pursued. Mimeo, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Dorward A, Chirwa E, Jayne TS (2010) The Malawi Agricultural Inputs Subsidy Programme, 2005/06 to 2008/09. Available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/AFRICAEXT/Resources/258643-1271798012256/MAIP_may_2010.pdf

FAO, IFAD, IMF, OECD, UNCTAD, WFP, The World Bank, the WTO, IFPRI and the UN HLTF (2011) Price volatility in food agricultural markets: policy responses. Mimeo

Gouel C, Jean S (2012) Optimal food price stabilization in a small open developing country. Policy research working paper 5943. The World Bank, Washington, DC

Human Development Network (HDN) and Poverty Reduction and Economic Management (PREM) Network (2008) Rising food and fuel prices: addressing the risks to future generations. Mimeo. The World Bank, Washington, DC

Ivanic M, Martin W (2008) Implications of higher global food prices for poverty in low-income countries. Policy research working paper 4594. The World Bank, Washington, DC

Ivanic M, Martin W, Zaman H (2011) Estimating the short-run poverty impacts of the 2010-11 surge in food prices. Policy research working paper 5633. The World Bank, Washington, DC

Jones WI (1995) The World Bank and irrigation. OED: a world bank operations evaluation study. Mimeo. The World Bank, Washington, DC

Martin W, Anderson K (2011) Policy research working paper 5645. The World Bank, Washington, DC

Mitchell D (2008) A note on rising food prices. Policy research working paper 4682. The World Bank, Washington, DC

Timmer CP (2010) Reflections of food crises past. Food Policy 35:1–11

Torero M (2011) Alternative mechanisms to reduce food price volatility and price spikes. Science review 21. Government Office for Science—Foresight Project on Global Food and Farming Futures, UK

Torero M (2012) Food prices: riding the rollercoaster. In: 2011 Global food policy report. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

von Braun J, Bouis H, Kumar S, Pandya-Lorch R (1992) Improving food security of the poor: concept, policy and programs. Occasional papers # 23. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

Wodon Q, Zaman H (2008) Rising food prices in Sub-Saharan Africa: poverty impact and policy responses. Policy research working paper 4738. The World Bank, Washington, DC

World Bank (2008) Framework document for proposed loans, credits and grants in the amount of US$ 1.2 billion equivalent for a Global Food Crisis Response Program. Mimeo. The World Bank, Washington, DC

World Bank—LAC (2008) Rising food prices: the World Bank’s Latin America and Caribbean Region position paper. Mimeo. The World Bank, Washington, DC

World Bank—South Asia Region (2010) Food price increases in South Asia: national responses and regional dimensions. The World Bank, Washington, DC

World Food Summit (1996) Rome declaration on world food security and world food summit plan of action. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome

Wright B (2009) International grain reserves and other instruments to address volatility in grain markets. Policy research working paper 5028. The World Bank, Washington, DC

Zaman H, Delgado C, Mitchell D, Revenga A (2008) Rising food prices: are there right policy choices? Dev Outreach 10(3):6–8, The World Bank, Washington, DC

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/) which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Torero, M. (2016). Consistency Between Theory and Practice in Policy Recommendations by International Organizations for Extreme Price and Extreme Volatility Situations. In: Kalkuhl, M., von Braun, J., Torero, M. (eds) Food Price Volatility and Its Implications for Food Security and Policy. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28201-5_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28201-5_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-28199-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-28201-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)