Abstract

The relationships between the five parental involvement components and student literacy were modelled using latent multilevel modeling. The models incorporated data from all 41 participating PIRLS countries. Outcomes for the components entered as fixed effects are presented. Models with random slopes at county level for two components establish whether their effect differs across countries. Comparing the outcomes of the multi-level models for different modeling approaches of the CDIF in the parental involvement constructs reveals the impact of CDIF.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Multilevel modeling

- Item response theory

- Cultural differences

- Parental involvement

- Reading literacy

- PIRLS

5.1 Method and Rationale for Latent Regression Models

After modeling parental involvement, we investigated its relationship with reading literacy using a three-level regression model in which students (level 1) were clustered within schools (level 2) and schools were clustered within countries (level 3). Although it is important to recognize that the countries participating in PIRLS-2011 cannot necessarily be regarded as being representative of the whole world, incorporating a country level in our analyses provides some indication whether the parental involvement influences reading achievement in countries worldwide. The majority of previous studies on parental involvement applied only to the USA.

In our multilevel model, the dependent variable was the reading literacy variable from the PIRLS dataset. To account for the unreliability of this outcome variable, five plausible values are available in the PIRLS dataset. All analyses were repeated for all five plausible values and then aggregated to overall estimates of fixed and random factors, thus incorporating the differences in standard errors for the different effect sizes (Von Davier et al. 2009). The sampling procedure was accounted for by including a student-class weight at the student level and a school weight at the school level. It is important to concurrently use school and student weights in the analyses, because schools were sampled first and then students were sampled within schools.

To assess the relationships between the components of interest and the reading literacy outcome, important determinants of student achievement such as gender and socioeconomic status (SES) were also included. The analytic framework described in Chap. 3 included questions that could be regarded as proxies for SES, such as “number of books in the home” and “highest educational level attained by one of the parents”. Together with gender, these variables were added as control variables.

We evaluated the different multilevel models for each set of estimates resulting from the measurement models described in Chap. 4. Having already compared the outcomes for the means on the latent scales for the different corrections for CDIF, comparing the results of the structural multilevel model reveals the extent to which CDIF may influence the relationship between parental involvement and students’ reading literacy, and level of control provided by the measurement models.

The five variables for the five parental involvement components were generated using the five IRT models considered in the previous chapter: the GPCM, the GPCM with 10 and 20 % country-by-item interaction, the GPCM with random item parameters and the bi-factor GPCM. We included the last four models to assess whether taking potential CDIF into account would direct toward different conclusions. For all five models, we obtained a posteriori estimates for the student parameters and entered these estimates as independent variables into the multilevel model.

For the GPCM, first an empty model (model 0) was estimated to see how the variance in the outcome variable is distributed over the three levels. Subsequently, control variables (student background characteristics) were added as fixed effects (model 1). The resulting model can be seen as a baseline to which the models, including the parental involvement variables of interest, can be compared. The separate parental involvement components were added as fixed effects on either the student level (i.e., components 1–4) or school level (component 5), resulting in models 2A–2E. We also created a model that included all five components simultaneously (model 3).

By entering the five components as fixed factors, the factor was assumed to have the same effect across all countries. However, in the context of this study, we also wanted to determine the extent of differences in the effects of parental involvement across countries. Therefore, we also considered a model with random slopes at the country level for the parental involvement components (model 4). A random slopes model includes a variance component for the slope of one or more predictor variables, while the other models may be considered special versions obtained by fixing parameters. The full model, a random intercepts-and-slopes model, with one component for parental involvement is given by:

where \( \epsilon_{ijk} \) is a normally distributed error term with variance \( VAR\left({\epsilon_{ijk}} \right) = \sigma^{2} \) that is independent over students i, schools j, and countries k. The first term on the right-hand side is a random intercept, decomposed as

where \( \gamma_{000} \) is the grand mean, and the other two terms are independent normally distributed error components with mean zero and variance \( VAR\left( {u_{0jk} } \right) = \xi_{0}^{2} \) and \( VAR\left( {v_{k} } \right) = \tau_{0}^{2} \). The regression coefficients \( \beta_{1} , \beta_{2} , \) and \( \beta_{3} \) pertain to gender, the number of books in the home, and the highest educational level attained by one of the parents, respectively. The regression coefficient for the parental involvement component is decomposed as

where \( \gamma_{400} \) is the average slope for the component over all countries and schools, and the two error terms have variances \( VAR\left( {u_{4jk} } \right) = \xi_{4}^{2} \) and \( VAR(u) = \tau_{4}^{2} \), respectively. Finally, random intercepts and random slopes are allowed to covary; at the country level this leads to a parameter \( COV\left( {v_{k} , u_{4k} } \right) = \tau_{04}^{2} \).

The fixed effects models are obtained by setting \( VAR(u) = \tau_{4}^{2} = 0 \), and the baseline models, model 0 and model 1, are obtained by removing the appropriate predictors.

To keep the model interpretable and relevant, only the components showing a meaningful effect in the fixed model were entered as covariates in the random-intercepts-and-slopes model.

We conducted all analyses using the software package Mplus version 7.11 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012).

5.2 Results of Latent Regression Models

The effects on student reading literacy were first modelled using the GPCM without correction for CDIF (Tables 5.1, 5.2, 5.3 and 5.4). Model 0 indicates that most of the variance in student achievement in reading literacy was situated at the student level (44 %; Table 5.1). Differences between countries were also considerable; 39 % of the variance could be accounted for by between-country differences. This was to be expected based on the large range of average country scores reported in the international report of PIRLS-2011 (Mullis et al. 2012).

As expected, model 1 indicated that gender and the two SES-indicators are important predictors of reading literacy. On average, girls outperformed boys by almost 13 points on the PIRLS-test. The number of books at home and the educational level of the parents are both positively related to reading achievement. The three background variables explain a considerable amount of variance; 40 % at school level and 62 % at country level. This suggests that a substantial part of the differences in achievement scores between PIRLS countries can be attributed to individual differences in student background characteristics.

In models 2A–2E, we explored the fixed effects of the different components of parental involvement, taken into account the effect of the three background variables (Table 5.2). The effect sizes of the background variables did not change noteworthy when the different components of parental involvement were included in the model. Parental report of literacy activities before their child starts in first grade, and helping with homework were both related to a student’s reading literacy, but each in a different way. Students of parents reporting spending more time on early literacy activities with their child showed higher achievement levels than those whose parents spent less time on these activities (the scale runs from high involvement to low involvement, therefore the effect in Table 5.2 appears as a negative score). This is in agreement with the results presented in the international report (Mullis et al. 2012). With regard to helping with homework, there is a negative relationship (this scale also runs from high involvement to low involvement, therefore the effect in Table 5.2 appears as a positive). Because of the large number of respondents recorded in the data (over 200,000 students), each relationship with achievement, even when very weak, is significant. Therefore, the relevance of these relationships was assessed in terms of changes in the achievement score if the predictor increased by one standard deviation. The standard deviation of early literacy activities was almost 1 (0.97, and thus excluded from this report). If parents’ perceptions of the time they spent on early literacy activities increased one point (i.e., from average to one standard deviation above the mean), the score of the student on the PIRLS test increased by nine points. On a scale with a mean of 500 and a standard deviation of 100, this could be considered a small effect. This also applies to the negative association between helping with homework and reading achievement. The standard deviation of this component was also 1, and the reduction in student achievement was 9.3 if parents reported that they spent one standard deviation more in time in helping their child.

At first glance, it seems that students whose parents had less positive views about school practices outperformed the classmates whose parents held more positive views. However, as the standard deviation of this scale was 1.6 and the effect size 5.1, the increase in scores was only three points. The same was true for students’ perception of parental involvement (decrease of almost three points) and school perception of parental involvement (increase of three points). These are very small effects.

Models 2A–2E revealed that for each of the five components, the percentages suggested hardly any alteration in the variance, as compared with model 1. Thus, in model 3, we entered the fixed effects for all components of parental involvement simultaneously (Table 5.3). The influence of early literacy activities and helping with homework increased slightly when the effects of the other components were held constant; variance increased to 15 % at student level, 46 % at school level, and 69 % at country level.

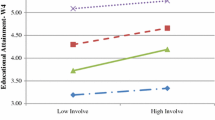

The next step was to estimate two models with random slopes at country level for early literacy activities and helping with homework, to determine whether the effects of components of parental involvement differed across countries. While recognizing this is still open for discussion, we considered these two components as showing a small, but meaningful relation with reading achievement. We included the three background variables as fixed effects in the random model (Table 5.4).

For early literacy activities we see a very small increase in the average overall effect, from –9.0 in model 2A to –8.7 in model 4. The variance over countries is 14.57; relative to the total variance in the outcome variable this is very small, but relative to the effect of early literacy activities, the effect is clearly larger. Ninety-five percent of the range of the slope over countries lay roughly between –37.5 and 20.5. A covariance of 27.25 indicated there was a relationship between the intercept of a country and the steepness of the slope within a country. A positive covariance means that the relationship between parental involvement and reading achievement is stronger in countries that performed strongly in the PIRLS test; a negative covariance means that the association between the predictor and dependent variable becomes stronger as the country average of reading achievement decreases. The standard error of the covariance for early literacy activities was larger than the covariance, indicating that there was no relation between the intercept and slope. From the variance components and the covariance, we obtained a correlation of 0.07, which must be considered small.

For helping with homework, the average effect size increased from 9.3 to 11.8. The variance of the slope over countries was 74.42; 95 % of the range of the slope over countries lay between –134.0 and 159.5, which can be considered substantial. Further, a positive covariance of 109.23 led to a correlation of 0.34, which is also substantial. As this scale runs from high involvement to low involvement, although the effect reported was positive, in truth it is a negative effect (more help = lower achievement). The positive covariance suggests that this negative association of helping with homework with achievement was stronger in high-performing countries.

To assess the impact of CDIF, we replicated the last analysis (Table 5.4) with the a posteriori estimates of the latent student parameters from all five IRT models (Table 5.5). Estimates from all models were very close and never more than one standard deviation away from the estimates under the GPCM. We conclude that CDIF did not bias the inferences.

References

Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., & Drucker, K. T. (2012). PIRLS 2011 international results in reading. Chestnut Hill, MA, USA: TIMSS&PIRLS International Study Center, Boston College.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide. (7th ed.) Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/Mplus%20user%20guide%20Ver_7_r3_web.pdf.

Von Davier, M, Gonzalez, E, & Mislevy, R. J. (2009). What are plausible values and why are they useful? In M. Von Davier & D. Hastedt (Eds.), IERI. monograph series. issues and methodologies in large-scale assessments (pp. 9–36). Hamburg: IER Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, a link is provided to the Creative Commons license, and any changes made are indicated. The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt, or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Punter, R.A., Glas, C.A.W., Meelissen, M.R.M. (2016). Relation Between Parental Involvement and Student Achievement in PIRLS-2011. In: Psychometric Framework for Modeling Parental Involvement and Reading Literacy. IEA Research for Education, vol 1. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28064-6_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28064-6_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-28710-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-28064-6

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)