Abstract

Residential segregation has been called the “structural linchpin” of racial stratification in the United States. Recent work has documented the central role it plays in the geographic concentration of poverty among African-Americans as well as the close connection between exposure to concentrated deprivation and limited life chances. Here we review trends in racial segregation and Black poverty to contextualize a broader analysis of trends in the neighborhood circumstances experienced by two groups generally considered to occupy the top and bottom positions in U.S. society: affluent Whites and poor Blacks. The analysis reveals a sharp divergence of social and economic resources available within the social worlds of the two groups. We tie this divergence directly to the residential segregation of African-Americans in the United States, which remains extreme in the nation’s largest urban Black communities. In these communities, the neighborhood circumstances of affluent as well as poor African-Americans are systematically compromised.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Residential segregation

- School segregation

- Racial segregation

- Hypersegregation

- Poverty concentration

- Poverty

- Neighborhood disadvantage

- Racial stratification

- Geographic mobility

Introduction

Residential segregation has been called the “structural linchpin” of racial stratification in the United States (Pettigrew 1979; Bobo 1989; Bobo and Zubrinsky 1996), and over time its role in the perpetuation of Black disadvantage (and White advantage) has become increasingly clear to social scientists (for a review, see Massey 2013). William Julius Wilson (1987) was the first to notice the rising concentration of poverty in Black inner city neighborhoods during the 1980s. Massey (1990) subsequently sought to explain this growing concentration of Black poverty using a simulation to demonstrate how rising rates of Black poverty interact with high levels of Black segregation to concentrate poverty in certain areas and neighborhoods. Massey and Denton (1993) went on to argue that by concentrating poverty, racial segregation created a uniquely harsh and disadvantaged social environment for poor African-Americans and residential circumstances with much fewer advantages for affluent African-Americans compared to Whites of similar social status.

In his analysis of the mathematics underlying Massey’s simulation exercise, Quillian (2012) demonstrated that concentrated poverty stemmed not simply from an interaction between Black poverty and Black segregation but was also affected by the level of geographic separation between poor and nonpoor Blacks as well as the degree of segregation between poor Blacks and others who were both nonpoor and non-Black. Given conditions that commonly prevail in metropolitan America, however, Quillian (2012, 370) gave his support to Massey’s theoretical argument. When African-Americans are highly segregated, increases in Black poverty are absorbed by a relatively small number of compressed, racially homogeneous neighborhoods, increasing the geographic concentration of poverty in ghetto areas.

Subsequent research has confirmed the close connection between Black segregation and geographically concentrated disadvantage and demonstrated the powerful negative influence of concentrated poverty on individual life chances (Sampson 2012; Massey and Brodmann 2014). Owing primarily to the persistence of racial residential segregation, poor African-Americans experience levels of neighborhood poverty, violence, and social disorder that are rarely, if ever, experienced by the poor of other groups (Peterson and Krivo 2010; Sampson 2012). Moreover, the high exposure of African-Americans to geographically concentrated disadvantage not only persists over the individual life cycle but also is maintained across the generations. Indeed, Sharkey (2013) found that half of all African-Americans nationwide had lived in the poorest quartile of urban neighborhoods for at least two generations, compared to just 7 % of Whites. Whereas in 1968 Otis Dudley Duncan argued that Black socioeconomic disadvantage was transmitted along the lines of race, in the twenty-first century, Sharkey shows how Black disadvantage is increasingly transmitted on the basis of place.

Here we review trends in the degree of Black residential segregation along with rates of Black and White poverty from 1970 to 2010 to assess the structural potential for concentrated poverty and how it has changed over time. We then examine trends in neighborhood conditions experienced by poor Whites and Blacks and compare them to those experienced by affluent Whites and Blacks. Our analysis documents the widening gap between the social worlds inhabited by those at the top and bottom of the U.S. socioeconomic hierarchy and underscores the powerful effect that segregation has in undermining the quality of the neighborhoods even of African-Americans.

Four Decades of Segregation and Poverty

Our analysis draws on census tract data obtained from the decennial censuses of 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010 as well as data from the 2008–2012 American Community Surveys for 287 consistently defined Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs; borrowing liberally from a dataset developed by Rugh and Massey 2014). Figure 2.1 shows trends in the degree of Black–White segregation from 1970 to 2010. The values are weighted averages of segregation indices computed for all MSAs, where weights are the proportion of all metropolitan Blacks living in each MSA. The trends thus represent changes in the degree of segregation experienced by the average Black metropolitan resident over time.

We measure segregation using the well-known index of dissimilarity , which gives the relative share of two groups that would have to exchange neighborhoods to achieve an even residential distribution (Massey and Denton 1988). We proxy neighborhoods using census tracts, which are small local areas averaging around 4,000 persons defined by the U.S. Census Bureau. In an even residential distribution each tract would replicate the racial composition of the metropolitan area as a whole. For example, if an MSA were 10 % Black and 90 % White, then evenness would be achieved when each tract was 10 % Black and 90 % White, yielding an index value of zero. In general, tract-based dissimilarity indices of 60 or greater are considered to be high, those between 30 and 60 moderate, and those under 30 low.

According to these criteria, average levels of Black-White segregation have remained in the high range throughout the past four decades. Nonetheless, levels of racial segregation have displayed a slow but steady decline over time, with the dissimilarity index going from 78 in 1970 to around 60 in 2010, a decline of about five points per decade. Although the trend in Black-White segregation may have been downward on average, Rugh and Massey (2014) found considerable variation across MSAs in the rate of decline. Their statistical analysis revealed that lower levels of Black segregation and more rapid shifts toward integration were predicted by small metropolitan population size, high Black socioeconomic status, low levels of anti-Black prejudice, permissive density zoning in suburbs, the presence of a college or university, larger concentrations of military personnel, and a small Black percentage. In general, therefore, metropolitan areas experiencing a decline in segregation over the past 40 years have been those of small size with a relatively small Black population of high socioeconomic status, with suburban zoning regimes that allow multi-unit housing, and a military base and/or colleges or universities in the metropolitan region. Obviously this profile does not fit the metropolitan areas where most African-Americans live.

Figure 2.1 also shows trends in Black and White poverty from 1970 to 2010. We define poverty as coming from a household within an income of $30,000 or less (the cutoff for receipt of a federal Pell college grant for low-income students). As can be seen, there is little evidence of any downward trend in the level of Black poverty over time. Indeed, the poverty rate rose from 34 to 40 % between 1970 and 1990; and although it fell to a rate of 35 during the economic boom of the 1990s by 2010, it had risen back to up 36 %, two points above where it stood in 1970. The rate of White poverty likewise rose between 1970 and 1990, going from 16 to 24 % before dropping back to 21 % in 2000 and then rising back up to 23 % in 2010. For both racial groups, we expect trends in the concentration of poverty generally to follow trends in the rate of poverty (Jargowsky 1997). Thus it should rise during the 1970s and 1980s, fall in the 1990s, and then rise again during the 2000s, though absolute levels of poverty concentration naturally will be much lower for Whites than Blacks.

As already noted, declines in Black-White segregation were quite uneven across regions, with high levels generally persisting in sizable poor Black communities located in the nation’s large metropolitan areas. In their analysis of 1980 census data, Massey and Denton (1989) went further to identify a subset of areas in which African-Americans were segregated along multiple geographic dimensions simultaneously, a pattern of intense isolation they labeled hypersegregation . In hypersegregated metropolitan areas, African Americans are highly segregated (index value above 60) on at least four of segregation’s five underlying geographic dimensions. Thus African-Americans were not only unevenly distributed across neighborhoods but also experienced high levels of isolation , living in nearly all-Black neighborhoods that were clustered tightly together to form a densely packed community located in and around the city center. In 1980, such areas housed a disproportionate share of all African-Americans. Although a recent analysis by Massey and Tannen (2015) revealed that the number of hypersegregated areas dropped sharply between 1970 and 2010, 34 % of all metropolitan Black residents still lived under conditions of hypersegregation 40 years later, with another 21 % living under conditions of “high” segregation (dissimilarity index above 60).

The top of Fig. 2.2 shows trends in Black-White segregation for the five most racially segregated metropolitan areas as of 2010. These data underscore how limited progress toward racial integration has been in the nation’s largest urban Black communities. In MSAs such as Milwaukee , New York, Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland—places with well-known and long-established Black ghettos—progress toward residential integration has been limited, with dissimilarity indices ranging narrowly between 73 and 80 even in the age of Obama. Among all hypersegregated areas, the average Black-White dissimilarity index fell from 79 in 1970 to 66 in 2010, and their ranks included St. Louis , where Blacks and Whites at present are bitterly divided over the killing of an unarmed Black teenager by a White police officer in the predominantly Black suburb of Ferguson .

Figure 2.2 also shows trends in Black-White dissimilarity among the five least segregated metropolitan areas in 2010. As can be seen, in smaller metropolitan areas with tiny Black populations levels of segregation, the dissimilarity index fell quite rapidly over the past four decades. In Provo, Utah , for example, the index fell from 83 in 1970 to just 18 in 2010. Of course, the Black population of Provo numbered just 4,012 in 2010 and was relatively affluent, not to mention Provo is a college town (home to Brigham Young University). The average dissimilarity index for all five areas went from 66 in 1970 to 19 in 2010, but the average size of the Black population was 2,600 and all five areas contained colleges or universities, again not a profile that applies to most Black metropolitan residents.

The link between the degree of Black segregation and the relative size of the Black population reflects changes in White racial attitudes since the civil rights era . In the 1960s, large majorities of White Americans supported racial segregation in principle, agreeing that Whites had a right to keep Blacks out of their neighborhoods and that African-Americans should respect that right. By the 1990s, however, the percentage of Whites expressing this viewpoint had fallen to single digits, and most had adopted a color-blind ideology of equal opportunity for all regardless of race (Schuman et al. 1998).

Despite the collapse of White support for segregation in principle, however, negative racial stereotypes remain firmly rooted in White social cognition and White respondents show little tolerance for associating with very many African-Americans in practice, especially in intimate settings such as neighborhoods and schools. On surveys, as the hypothetical number of Black students or neighbors increases, larger and larger shares of White respondents express discomfort, declaring a reluctance to enter a neighborhood and expressing a desire to leave (Charles 2003, 2006). Even after controlling for a neighborhood’s property values, crime rates , and school quality, the likelihood that a White subject would be willing to purchase a home in a neighborhood declines sharply as the percentage of Blacks rises (Emerson et al. 2001).

Under these circumstances, in metropolitan areas with small Black populations, Whites can simultaneously honor their ideological commitment to equal opportunity and satisfy their desire not to share schools or neighborhoods with many Black people. In Provo, for example, the Black percentage is just 0.7 %, so under conditions of complete integration (a Black-White dissimilarity index of zero) each neighborhood would be just 0.7 % Black, which is well within White tolerance limits. In contrast, Milwaukee County is 27 % Black, so complete integration there would yield neighborhoods that were 27 % Black, which is well beyond the comfort level of most Whites—hence the current pattern of high, stubborn levels of segregation in metropolitan areas containing large Black communities but rapid shifts toward integration in areas where few African-Americans actually live.

Nonetheless, patterns of racial segregation did change after the civil rights era. Whereas virtually all metropolitan areas were highly segregated by race in 1970, 40 years later, segregation levels vary widely across metropolitan areas. Indeed, from 1970 to 2010 the standard deviation of Black-White dissimilarities rose from 10.2 to 11.2. At the same time, the standard deviation of Black poverty rates fell from 10.1 to 8.2. With stable means and declining variability in rates of Black poverty but declining means and rising variability with respect to Black segregation, the geographic concentration of Black poverty over time has increasingly come to be determined by inter-metropolitan variation in the degree of Black residential segregation.

Poverty and Privilege in Black and White

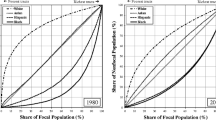

Historically, poor African-Americans have been concentrated disproportionately at the bottom of the U.S. socioeconomic distribution while affluent Whites have congregated near the top. As noted earlier, we define poverty as having a household income of $30,000 or lower; for our purposes we define affluence as having a household income of $120,000 or greater. In order to examine shifts in the size of the gap between the top and bottom of American society, therefore, we chart trends in the social and economic characteristics of neighborhoods occupied by the affluent and poor of both races, with dollar amounts expressed in constant 2010 dollars. Figure 2.3 begins the analysis by plotting trends in the proportion of households with incomes of $30,000 or lower in the neighborhoods inhabited by affluent Blacks and poor Blacks, as well as affluent Whites and poor Whites.

Figure 2.3 indicates the degree to which Blacks and Whites at the top and bottom of the income distribution are exposed to poverty within the social worlds defined by their neighborhoods. Obviously poor African-Americans have always experienced a higher concentration of poverty than other groups, and as expected, changes in the degree of poverty concentration closely follow trends in the rate of poverty generally. In 1970 the average poor African-American lived in a neighborhood that was 40 % poor, and this figure increased to 49 % by 1990 before dropping to 44 % in 2000 and then edging back up to 45 % in 2010. Although affluent African-Americans are less exposed to neighborhood poverty than poor Blacks (25 % and 27 %, respectively), in 1970 and 1980 their exposure to poverty was on a par with levels typically experienced only by poor Whites, whose respective figures stood at 23 and 26 % in the 2 years. In contrast, affluent Whites experienced neighborhood poverty rates of just 11 and 13 %, indicating their privileged status in the American status hierarchy.

As levels of racial segregation moderated after 1980, however, affluent African-Americans began to achieve greater geographic separation from the poor, and the poverty rate in affluent Black neighborhoods dropped from 27 % to 23 % between 1980 and 2010. The degree of concentrated poverty experienced by poor Whites rose, however, in keeping with the overall rise in levels of White poverty, with concentration going from 26 to 32 % over the period. Affluent Whites, of course, continued to experience the least exposure to poverty within their neighborhoods across the four decades, with the degree of poverty concentration rising slowly from 13 to 17 % but always remaining well below the levels observed for other race-class groups.

In summary, as of 2010 we observe a clear hierarchy with respect to neighborhood disadvantage, with poor African-Americans experiencing by far the greatest concentration of poverty (45 %), followed by poor Whites (32 %), affluent Blacks (23 %), and affluent Whites (17 %). This ordering is important because research indicates that the high rate of neighborhood disadvantage commonly experienced by poor Blacks is the principal structural reason for the remarkable lack of socioeconomic progress among African-Americans since the end of the civil rights era (Sharkey 2013).

Figure 2.4 continues the analysis by looking at the other end of the spectrum of neighborhood quality, focusing on exposure to neighborhood affluence by examining trends in the percentage of households earning $120,000 or more in neighborhoods occupied by the affluent and poor of both races. In keeping with affluent Whites experiencing the least exposure to poverty, they also display by far the highest exposure to affluence within their social worlds. Although the percentage of affluent households in the neighborhood of the average affluent White person fell slightly from 22 % to 20 % from 1970 to 1980, thereafter the figure steadily rose to reach 30 % in 2010. Once again, affluent African-Americans experienced great difficulty translating their income attainments into improved neighborhood circumstances in 1970, achieving only the concentration of affluence attained by poor Whites, at just under 10 %. As racial segregation moderated over time, however, the concentration of Black affluence steadily rose, until by 2010 the average affluent African-American lived in a neighborhood in which 22 % of the households were also affluent.

Although exposure to affluent households within neighborhoods also rose somewhat for poor Blacks and Whites between 1970 and 2010, the increase was quite modest: the percentage affluent rose from 9 to 13 % for poor Whites and from 4 to 7 % for poor Blacks. In general, then, the range of exposure to affluence, along with the benefits it confers, widened substantially over the decades, as indicated clearly in the figure. Even though affluent African-Americans improved their standing with respect to poor Whites and poor Blacks, however, they by no means caught up to affluent Whites, replicating the clear hierarchy observed in Fig. 2.3, with affluent Whites on top, followed in order by affluent Blacks, poor Whites, and poor Blacks.

Exposure to affluence within neighborhoods necessarily implies exposure to attributes and characteristics associated with affluence, thus generating a range of benefits for residents. One such attribute is education, and Fig. 2.5 shows the percentage of college graduates within neighborhoods occupied by affluent and poor Blacks and Whites. Holding college degrees confers status and prestige, of course, but college graduates also vote at higher rates to generate more political influence, exhibit lower rates of crime and delinquency, express greater interpersonal tolerance and trust, are more involved in cultural and educational institutions, and generally exhibit healthier lifestyles, thus creating a more salubrious, nurturing, and supportive neighborhood environment.

On this important indicator of neighborhood advantage, we once again observe the familiar pattern of racial and class stratification and a growing spread between race-class segments over time. Again affluent Whites experience the highest exposure to college graduates and poor Blacks experience the least, with affluent Blacks and poor Whites falling in-between. From 1970 to 2010 the percentage of college graduates in affluent White neighborhoods rose from 19 to 44 %, whereas the share rose only from 5 to 19 % in poor Black neighborhoods, widening the gap from 14 to 25 points. As before, affluent Blacks were only able to experience the low levels of exposure to college graduates in 1970; but over time they again improved their relative standing. By 2010 the average affluent African-American lived in a neighborhood where 33 % were college graduates, compared to a figure of 27 % for poor Whites. Despite this improvement relative to poor Whites, affluent Blacks still had not closed the gap with affluent Whites, which remained fairly constant from 2000 to 2010.

The final indicator of neighborhood advantage we consider is potential home wealth , which we measure by multiplying median home values within neighborhoods by the proportion of homeowners in the same neighborhoods. The product, plotted in Fig. 2.6, indicates the amount of wealth potentially accessible to the average neighborhood resident in the form of home equity. As can be seen, in 1970 the average affluent White person lived in a neighborhood where potential home wealth stood at $105,000 compared to only $29,000 in the neighborhood of the average poor Black person (figures once again in constant 2010 dollars). Among affluent African-Americans, potential home wealth was only $50,000, a figure even lower than the $56,000 figure for poor Whites.

Over time potential home wealth increased for all race-class groups, but the increase was greatest for affluent Whites, whose potential home wealth stood at $275,000 in 2010. Although affluent African-Americans were again able to improve their standing relative to poor Whites, they were unable to close the gap with affluent Whites. As of 2010, their potential home wealth stood at around $193,000, roughly $82,000 below affluent Whites (compared to a gap of $55,000 in 1970) but nonetheless above the value of $136,000 experienced by poor Whites. As expected, poor African-Americans displayed the least access to potential home wealth, with a figure of just $81,000 in 2010, only 29 % of the potential home wealth accessible to affluent Whites in their neighborhoods.

In addition to the financial cushion provided by access to wealth, home values also translate directly into access to higher quality education given that public schools in the United States are financed mostly by real estate taxes. Thus the 3.4-to-1 differential in potential home wealth between affluent Whites and poor Blacks translates into a comparable differential with respect to school funding, ultimately producing a profound gap in the quality of education available to those at the top and bottom of American society. The connection between racial segregation and stunted educational achievement among Blacks is very well established empirically (Goldsmith 2009; Billings et al. 2012; Rothstein 2004, 2014). The close connection between school segregation and residential segregation is confirmed by the data in Fig. 2.7, which displays the relationship across states between the level of neighborhood segregation (Black-White dissimilarities computed for tracts) and the degree of educational segregation (Black-White dissimilarity between school districts using state-level data obtained from the National Center for Educational Statistics; http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/bat/). As can be seen, residential segregation explains 61 % of the variance in school segregation across states, suggesting that the continued segregation of African-Americans thus explains much of Black underachievement in the educational realm.

Segregation and the Divergence of Social Worlds

Earlier we explained that geographically concentrated poverty follows directly from two fundamental structural conditions in society: a high rate of minority poverty and a high degree of minority residential segregation, a relation now established both mathematically and empirically. We also noted that although average levels of Black residential segregation have fallen in the past four decades, the declines have been highly uneven and inter-metropolitan variation in the degree of segregation has increased. In contrast, levels of Black poverty have remained fairly stable, on average, and inter-metropolitan variability has decreased. Under these circumstances we would expect to observe a significant positive association between Black-White segregation and the concentration of Black poverty. To the extent that Whites are disproportionately affluent, of course, a high degree of Black-White segregation also tends to concentrate White affluence, as shown in Fig. 2.4. Thus we expect variation in racial residential segregation to substantially affect the size of the gap in neighborhood circumstances experienced by poor Blacks and affluent Whites in American society, that is, between the social worlds of the most affluent and poorest segments of the nation.

Figure 2.8 illustrates this relationship through a scatterplot showing the ratio of the average percentage affluent in neighborhoods occupied by affluent Whites (indicating the neighborhood privilege enjoyed by those at the top of American society) to the average percentage affluent in neighborhoods occupied by poor Blacks (indicating the relative lack of neighborhood privilege suffered by the bottom of U.S. society) expressed as a function of the level of Black-White segregation. The diagram reveals an obvious positive relationship, confirming the close connection between segregation and race-class inequality in the United States.

As can be seen, as the degree of racial segregation rises, the gap between affluent White and poor Black neighborhoods with respect to the rate of affluence steadily rises. According to the estimated equation, shifting the Black-White dissimilarity index from 15 to 80 (roughly the observed range of Black-White segregation) would raise the size of the gap from a ratio of 1.5 to 5.3. Although the equation does not control for the many other factors that might be expected to influence the size of the gap between those at the top and bottom of American society, it nonetheless illustrates the degree to which segregation by itself operates to concentrate geographical advantages and disadvantages , as demonstrated analytically by Quillian (2012) and empirically by a growing number of studies (cf. Massey and Denton 1993; Sampson 2012; Sharkey 2013; Massey and Brodmann 2014).

Figure 2.9 repeats the analysis using the ratio of affluent White to poor Black potential housing wealth to reveal an even stronger relationship between segregation and the gap in neighborhood access to wealth. Shifting levels of Black-White segregation from their minimum to maximum would raise the housing wealth gap from a ratio from 1.4 to 3.8. Black residential segregation thus goes a long way toward explaining the savage neighborhood inequalities in wealth that increasingly separate poor African-Americans from affluent Whites in American society today.

Inequality in Hypersegregated America

Results from the foregoing sections reveal sharply rising disparities in the neighborhood circumstances experienced by those at the bottom and top of the American socioeconomic distribution. Whether we consider exposure to poverty, concentrated affluence, exposure to college graduates, or potential home wealth, the gap in the quality of the social worlds inhabited by affluent Whites and poor Blacks has increased steadily over the past four decades. The gap between affluent Whites and poor Whites has also increased, and although affluent Blacks have gained ground on poor Whites as their neighborhood circumstances have improved, they have not come close to closing the gap with respect to affluent Whites.

These results prevail across U.S. metropolitan areas generally, including many that have displayed falling levels of Black-White segregation over the decades and are now characterized by moderate rather than high levels of racial segregation. However, roughly a third of all Black metropolitan residents still lived under conditions of hypersegregation in 2010, and in this section, we consider the changing fortunes of different race-class groups living under conditions of the most extreme form of residential segregation seen in the United States. Figure 2.10 begins the analysis by showing trends in exposure to neighborhood poverty experienced by different race-class groups in the 21 metropolitan areas that were hypersegregated as of 2010.

Although the trends in poverty concentration are similar to those observed across metropolitan areas generally (see Fig. 2.3), in hypersegregated areas the levels of Black poverty concentration are systematically higher. The percentage poor in the neighborhood of the average poor Black resident of a hypersegregated area thus rises from 40 % in 1970 to a peak of 53 % in 1990 before dipping and rising again to stand at 51 % in 2010. In addition, rather than decreasing as in Fig. 2.3, the concentration of poverty experienced by affluent African-Americans hardly changes at all and affluent African-Americans fail to improve their geographic position relative to poor Whites. In 2010 the exposure of affluent Blacks to poverty was 30 % greater in hypersegregated areas compared with all metropolitan areas (30 % compared to 23 %) and the exposure of poor Blacks to poverty was 12 % greater (50.5 % compared to 45 %). Thus high levels of Black residential segregation severely constrain the ability of affluent Blacks to limit their exposure to poverty and its problems (see Pattillo 2013).

We observe the same pattern of change over time with respect to exposure to affluence, only in reverse, as shown in Fig. 2.11. Under conditions of hypersegregation, both affluent and poor African-Americans experience less exposure to affluence in their neighborhoods relative to those in metropolitan areas generally, and once again affluent Blacks are unable to distance themselves geographically from the neighborhood circumstances experienced by African-Americans across metropolitan areas generally. As of 2010, the average affluent African-American living in a hypersegregated area experienced an affluence rate of just 16 % compared to 22 % for affluent African-Americans across metropolitan areas generally. Under conditions of the most intense segregation, in other words, affluent African-Americans experienced just 73 % of the neighborhood affluence experienced by those in all metropolitan areas.

Figure 2.12 shows trends in neighborhood exposure to college graduates within neighborhoods of hypersegregated metropolitan areas and demonstrates once again how affluent African-Americans are less able to achieve residential contact with this advantaged group under conditions of high residential segregation and are unable to move much above the geographic position of poor Whites. Whereas the average affluent Black resident lived in a neighborhood where 33 % had graduated from college (compared with 27 % for poor Whites, as shown in Fig. 2.5) when averaged across all metropolitan areas, the average affluent Black person living in a hypersegregated metropolitan area lived in a neighborhood where only 30 % were college graduates (compared with 26 % among poor Whites). Under conditions of hypersegregation, the most affluent African-Americans achieve neighborhood circumstances that are little better than those achieved by poor Whites.

Finally, Fig. 2.13 demonstrates the especially pronounced effect of hypersegregation on potential home wealth. Not only do poor and affluent African-Americans in hypersegregated metropolitan areas experience less access to housing wealth than those in all metropolitan areas, but the shortfalls are quite dramatic. As of 2010, the typical affluent African-American lived in a neighborhood with $193,000 in potential home wealth when averaged across all metropolitan areas, but only $123,000 when averaged across hypersegregated areas (see Fig. 2.6). Among poor African-Americans, potential home wealth averaged $81,000 across all metropolitan but only $62,000 in hypersegregated areas. Thus hypersegregation reduced access to home wealth by 23 % for poor Blacks and 37 % for affluent Blacks.

Conclusion

In any metropolitan area, resources are unevenly distributed in space, and in order to gain full access to opportunities in society, people must be free to move. In the United States, especially, geographic mobility has always been part and parcel of economic mobility (Park 1926). As members of different ethnic groups have moved upward economically, they have sought to translate their economic gains into improved neighborhood circumstances, gaining access to better schools, lower crime rates, more supportive peer groups, lower insurance rates, and higher home values (Massey and Denton 1985). By moving up the residential ladder, they put themselves and their children in a better position to achieve additional socioeconomic mobility .

For African-Americans, however, the translation of economic mobility into residential mobility and improved neighborhood conditions has historically been thwarted by segregation and the prejudice and discrimination that create and maintain it (Massey and Denton 1993). Owing to the combination of high segregation and high poverty, the concentration of poverty in Black neighborhoods has persisted and in many ways deepened over the decades. As a result, a large share of African-Americans has become “stuck in place,” passing place disadvantage and its deleterious effects from generation to generation (Sharkey 2013). Although poor African-Americans actually move quite frequently, each move simply replicates the status quo of place disadvantage (Sampson 2012).

Our findings here reveal both continuity and change with respect to racial residential segregation in the United States. Whereas racial segregation was universal across metropolitan areas in 1970, by 2010 it had declined in many areas, particularly those of lesser size with smaller and more affluent Black populations, more permissive density zoning, and lower levels of racial prejudice . Although Whites no longer supported segregation in principle, they remained concerned about its implications in practice and expressed reluctance to live in neighborhoods with more than a small share of African-Americans, leading to rapid desegregation in many metropolitan areas but persistently high segregation in the nation’s largest Black communities, with hypersegregation prevailing in 21 metropolitan areas containing around a third of Black metropolitan residents.

In this context, segregation has emerged as a major structural determinant of exposure to neighborhood advantage and disadvantage in American society. Whether we consider the concentration of poverty, access to affluence, exposure to college graduates, or potential home wealth, the differential in neighborhood quality between those at the top and bottom of the American social hierarchy has steadily widened over the past four decades, and as of 2010 the size of this gap was substantially determined by the degree of Black-White segregation prevailing in different metropolitan areas. The higher the level of racial segregation in an area, the greater the inequality in the social worlds defined by circumstances within affluent White and poor Black neighborhoods; the greater the level of racial segregation across neighborhoods, the greater the degree of segregation within schools.

Our focused analysis of neighborhood trends in hypersegregated areas further demonstrated the power of segregation not only to compromise the neighborhood circumstances of poor African-Americans but also to limit the ability of affluent Black residents to improve their geographic position in urban society. Although affluent African-Americans were unable to close the gap with affluent Whites in terms of exposure to affluence, education, and wealth over the past four decades, across metropolitan areas they were able to improve their geographic situation relative to poor Whites. In hypersegregated areas, however, this was not the case. Not only was the quality of neighborhoods inhabited by affluent Blacks lower in absolute terms compared to their affluent counterparts across metropolitan areas generally, but also their neighborhood circumstances improved little relative to those experienced by the very poorest of Whites. These findings confirm what social scientists have long known: Residential segregation continues to be the structural linchpin in America’s system of racial stratification.

Beyond its role in creating and perpetuating the Black urban underclass, recent evidence suggests the pernicious effects of persistent, high segregation need our focus because they are likely not limited to just one group. It may be spreading to Hispanics as well. Although Massey and Denton (1989) failed to identify any metropolitan area in which Hispanics were hypersegregated in 1980, by 2000 Wilkes and Iceland (2004) found that the two largest Hispanic communities—New York and Los Angeles—had both become hypersegregated, and according to Rugh and Massey (2014), Hispanic segregation is generated by the same factors that segregate African-Americans. In addition, a large share of Hispanics are undocumented and lack any social, economic, or civil right in the United States, and Hall and Stringfield (2014) find that Hispanic-White segregation rises as the estimated prevalence of undocumented migrants in the population increases. In the United States, therefore, we may be gravitating to a new racial order with Whites (and possibly Asians, given their educational income and levels) occupying privileged social worlds at the top of the socioeconomic hierarchy and Blacks and Hispanics inhabiting positions of concentrated disadvantage at the bottom.

References

Billings, Stephen B., David J. Deming, and Jonah E. Rockoff. 2012. School segregation, educational attainment and crime: Evidence from the end of busing in Charlotte-Mecklenburg (NBER Working Paper 18487). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bobo, Lawrence D. 1989. Keeping the linchpin in place: Testing the multiple sources of opposition to residential integration. International Review of Social Psychology 2: 305–323.

Bobo, Lawrence, and Camille L. Zubrinsky. 1996. Attitudes on residential integration: Perceived status differences, mere in-group preference, or racial prejudice? Social Forces 74(3): 883–909.

Charles, Camille Z. 2003. The dynamics of racial residential segregation. Annual Review of Sociology 29: 167–207.

Charles, Camille Z. 2006. Won’t you be my neighbor? Race, class and residence in Los Angeles. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Duncan, Otis D. 1968. Inheritance of poverty or inheritance of race? In Understanding poverty, ed. Daniel P. Moynihan, 85–110. New York: Basic Books.

Emerson, Michael O., George Yancey, and Karen J. Chai. 2001. Does race matter in residential segregation? Exploring the preferences of White Americans. American Sociological Review 66(6): 922–935.

Goldsmith, Pat Rubio. 2009. Schools or neighborhoods or both? Race and ethnic segregation and educational attainment. Social Forces 87(4): 1913–1942.

Hall, Matthew, and Jonathan Stringfield. 2014. Undocumented migration and the residential segregation of Mexicans in new destinations. Social Science Research. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.03.009.

Jargowsky, Paul A. 1997. Poverty and place: Ghettos, barrios, and the American city. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Massey, Douglas S. 1990. American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. American Journal of Sociology 95: 1153–1188.

Massey, Douglas S. 2013. Inheritance of poverty or inheritance of place? The emerging consensus on neighborhoods and stratification. Contemporary Sociology 42: 690–697.

Massey, Douglas S., and Stefanie Brodmann. 2014. Spheres of influence: The social ecology of racial and class inequality. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Massey, Douglas S., and Nancy A. Denton. 1985. Spatial assimilation as a socioeconomic outcome. American Sociological Review 50: 94–105.

Massey, Douglas S., and Nancy A. Denton. 1988. The dimensions of residential segregation. Social Forces 67: 281–315.

Massey, Douglas S., and Nancy A. Denton. 1989. Hypersegregation in U.S. metropolitan areas: Black and Hispanic segregation along five dimensions. Demography 26: 373–393.

Massey, Douglas S., and Nancy A. Denton. 1993. American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Massey, Douglas S., and Jonathan Tannen. 2015. A research note on trends in Black hypersegregation. Demography 52: 1025–1034.

Park, Robert. 1926. The urban community as a spatial pattern and a moral order. In The urban community, ed. Ernest W. Burgess and Robert E. Park, 3–18. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pattillo, Mary. 2013. Black picket fences: Privilege and peril among the Black middle class, 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Peterson, Ruth D., and Lauren J. Krivo. 2010. Divergent social worlds: Neighborhood crime and the racial-spatial divide. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Pettigrew, Thomas. 1979. Racial change and social policy. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 441: 114–131.

Quillian, Lincoln. 2012. Segregation and poverty concentration: The role of three segregations. American Sociological Review 77(3): 354–379.

Rothstein, Richard. 2004. Class and schools: Using social, economic, and educational reform to close the Black-White achievement gap. Washington, DC/New York: Economic Policy Institute and/Teachers College Press.

Rothstein, Richard. 2014. The racial achievement gap, segregated schools, and segregated neighborhoods—A constitutional insult. Race and social problems 6, doi:10.1007/s12552-014-9134-1.

Rugh, Jacob S., and Douglas S. Massey. 2014. Segregation in Post-Civil Rights America: Stalled integration or end of the segregated century? The DuBois Review: Social Science Research on Race 11(2): 202–232.

Sampson, Robert J. 2012. Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Schuman, Howard, Charlotte Steeh, Lawrence D. Bobo, and Maria Krysan. 1998. Racial attitudes in America: Trends and interpretations. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Sharkey, Patrick. 2013. Stuck in place: Urban neighborhoods and the end of progress toward racial equality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wilkes, Rima, and John Iceland. 2004. Hypersegregation in the twenty-first century: An update and analysis. Demography 41(1): 23–36.

Wilson, William Julius. 1987. The truly disadvantaged: The inner city, the underclass, and public policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 2.5 License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.5/) which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the work’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if such material is not included in the work’s Creative Commons license and the respective action is not permitted by statutory regulation, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to duplicate, adapt or reproduce the material.

Copyright information

© 2016 Educational Testing Service

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Massey, D.S., Tannen, J. (2016). Segregation, Race, and the Social Worlds of Rich and Poor. In: Kirsch, I., Braun, H. (eds) The Dynamics of Opportunity in America. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25991-8_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25991-8_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-25989-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-25991-8

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)