Abstract

This chapter considers age, period and cohort (APC) as different sources of health-related change. Age (or, life course) effects are individual, often biological, sources of change, whilst periods and cohorts can be thought of as social contexts affecting individuals that reside within them. Due to the mathematical confounding of age, period and cohort, careful consideration of each is important – otherwise what appears to be, for example, a period (year) effect could in fact be a mixture of age and cohort processes. Naive life course approaches could thus produce misleading results when APC effects are not all considered. However, the mathematical confounding also often makes modelling all three effects together impossible, and the dangers of attempting to do so, or of ignoring one effect without critical forethought, is illustrated through the example of the obesity epidemic. This example uses Yang and Land’s Hierarchical APC model which it is claimed (incorrectly) solves the identification problem. Finally, we suggest a flexible multilevel framework that extends Yang and Land’s model, and by making relatively strong assumptions (in this case that there are no long-run period trends) can model age, period and cohort effects robustly and explicitly, so long as those assumptions are correct. This is illustrated using health data from the British Household Panel Survey. We argue that this theory driven approach is often the most appropriate for conceptualising APC effects, and producing valid empirical inference about both individual life courses and the spatial and temporal contexts in which they exist.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Monte Carlo Markov Chain

- Cohort Effect

- General Health Questionnaire

- Deviance Information Criterion

- Micro Model

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

Age, period and cohort (APC) effects represent three distinct ways in which health can change over time, and researchers across the social and medical sciences have long been interested in how to differentiate and understand these changes. First, individuals can age, meaning that they change as they progress through their life course. Second, change can occur over time due to differences between cohort groups, whereby as new cohorts replace old cohorts, the social composition (and thus the health) of society as a whole can change. Third, and finally, change can occur as a result of period effects, whereby passage through time results in a change in health, regardless of the age of the individual. Suzuki (2012, p. 452) demonstrates the difference between these with the following fictional dialogue:

- A::

I can’t seem to shake off this tired feeling. Guess I’m just getting old. [Age effect]

- B::

Do you think it’s stress? Business is down this year, and you’ve let your fatigue build up. [Period effect]

- A::

Maybe. What about you?

- B::

Actually, I’m exhausted too! My body feels really heavy.

- A::

You’re kidding. You’re still young. I could work all day long when I was your age.

- B::

Oh, really?

- A::

Yeah, young people these days are quick to whine. We were not like that. [Cohort effect]

Understanding what combination of APC causes changes in health is of importance to many researchers, especially since different combinations of APC can have different public health policy implications. Unfortunately, meaningfully partitioning change into these three dimensions with statistical methods is far from straightforward, because age, period and cohort are exactly linearly dependent. This chapter considers the very serious implications of this ‘identification problem’ for longitudinal and life course research. Whilst the focus will be on health, the methodological and conceptual issues apply across the social sciences and beyond.

The chapter is structured as followed. We first outline the APC identification problem, and why simply controlling for age, period and cohort, as you might for imperfectly co-linear variables, does not work in the case of age, period and cohort. We show that the identification problem needs to be carefully considered whenever life course or longitudinal change is modelled, and that naïve models can radically reassign effects between age, period and cohort, producing misleading results. Next, we outline some proposed solutions to the identification problem, focusing on Yang and Land’s Hierarchical Age-Period-Cohort (HAPC) model (Yang and Land 2006, 2013), and, using the example of the obesity epidemic, show how they often do not work. Finally, we outline what we consider to be best practice when considering APC effects, by extending the HAPC model, and demonstrate this with an example examining APC effects on mental health (measured by the General Health Questionnaire) using the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS). We argue that whilst there is no method that can mechanically separate APC effects in all scenarios, when good theory is used to make robust assumptions regarding APC effects, researchers can often make useful and non-arbitrary inference.

The Age-Period-Cohort Identification Problem

It is well known that in any dataset, the variables age, period and cohort will be perfectly correlated, such thatFootnote 1:

As such, if we know the value of two of these variables, we will automatically know the value of the third. Consequently, when the true underlying process affecting a dependent variable includes linear effects of some or all of APC, there is a risk that we will pick the wrong combination, given that we could swap a term for the combination of the other two terms without changing the data. For example, take a contrived hypothetical process in which, say, an individual’s level of health is affected by all of age, period and cohort, each with an effect size of 1:

Here, health improves (by 1 unit) as an individual gets older (by 1 year), improves for everyone as time passes, and is better amongst people who were born later. Substituting Period with Age + Cohort, we get

And substituting Age + Cohort for Period gives us

There will be no differences between the datasets generated by each of these three processes – they will be indistinguishable. There are important implications of this hypothetical illustration for researchers considering life course and longitudinal data. Say Eq. 10.3 was the true underlying process. Were we to estimate the effects found in Eq. 10.4, we would have erroneously found zero importance of life course processes, and found an effect of time that was simply not present. The modelling choices that individuals take will affect the results that they could find. A researcher may, for example, diligently control for a potential period effect (in the hope of estimating an unbiased age effect), and in so doing completely miss the very age effect (s)he was hoping to find. As such the APC identification problem should be a concern not just to researchers wanting to find all three APC effects, but to any longitudinal and life course researcher who wishes to model any of the APC effects robustly.

Unfortunately, there is no satisfactory solution to this exact collinearity. The problem is that the collinearity is present in the underlying process that creates the data and therefore in the population as a whole (not just in the sample). This means that neither a more sophisticated model, nor a larger dataset, will solve the problem. However as we see in the next section, a number of solutions to the identification problem have been proposed, many of which fail to understand the impossibility of what they try to do:

The continued search for a statistical technique that can be mechanically applied always to correctly estimate the effects is one of the most bizarre instances in the history of science of repeated attempts to do the logically impossible (Glenn 2005, p. 6).

‘Solutions’ to the APC Identification Problem

The most common ‘solution’, and that suggested first by Mason et al. (1973), is to constrain certain parameters in a model to be equal.Footnote 2 Thus, each age, period and cohort group is entered into a regression model as a dummy variable, but two groups are combined as if they were a single group. This means that the dependency in Eq. 10.1 no longer applies (that is, it is no longer possible to always be sure of the value of one of the APC variables if you know the value of the other two). However, as Mason et al. recognised (but unfortunately many who use the Mason et al. method do not), solving the dependency in the model does not solve the dependency in the real world (Glenn 1976, 2005; Osmond and Gardner 1989). Whilst the model will produce an answer, there is no way of knowing whether that answer is correct unless we know that the constraint imposed is exactly correct. Thus whilst saying that individuals born in 1960 are substantively the same as those born in 1961 may seem innocuous, such an assumption could have a profound effect on the estimated results, and produce very different results from models using other apparently innocuous assumptions. Crucially, all of these models will have identical model fit statistics, meaning there is no way of choosing one constraint over another without strong prior knowledge. Other models use similar constraints, for example using aggregated groups for one of APC similarly constrains the parameters within those groups, for example see Page et al. (2013). These models are subject to the same problem – the identification problem is merely hidden beneath coarser data. Unless there is very good theory to believe that the groupings imposed are exactly valid, the model will generally fail to produce correct inference.

In recent years more solutions to the identification problem have been proposed.Footnote 3 This section now focusses on one of these – Yang and Land’s Hierarchical APC (HAPC) model (Yang and Land 2006, 2013).

The HAPC model conceptualises period and cohorts as contexts in which individuals (of a given age) reside. This structure makes repeated cross-sectional data (that is survey data with multiple surveys over time) apparently suitable to be modelled with a multilevel cross-classified structure (Browne et al. 2001), whereby individuals are nested within cohort groups and periods of time, but periods are not nested within cohort groups or vice-versa meaning a simple hierarchical structure is not possible (see Fig. 10.1). Thus, the model is specified algebraically as follows:

The dependent variable, \( {y}_{i\left({j}_1{j}_2\right)} \) is measured for individuals i in period j1 and cohort j2. The ‘micro’ model has linear and quadratic age terms, with coefficients \( {\beta}_1 \) and \( {\beta}_2 \) respectively, a constant that varies across both periods and cohorts, and a level-1 residual error term. The ‘macro’ model defines the intercept in the micro model by a non-varying constant \( {\beta}_0 \), and a residual term for each period and cohort. The period, cohort and level-1 residuals are all assumed to follow Normal distributions, each with variances that are estimated.

Structural diagram of the HAPC model. Individuals, of different ages, are nested within periods, and within a cohort group. This is cross-classified because periods do not nest within cohort groups, nor vice-versa (Adapted from Bell and Jones (2014a) figure 1)

This is an appealing conceptual design: “treating periods and cohort as contexts, and age as an individual characteristic, is intuitive to some degree because we move from one period to another as time passes, and we belong to cohort groups that have common characteristics, whereas aging is a process that occurs within an individual” (Bell and Jones 2014a, p. 340). However, Yang and Land go beyond this, arguing that this model does not incur the identification problem, because (a) the age effect is specified as a quadratic equation, and (b) because the multilevel model treats age differently from periods and cohorts:

the underidentification problem of the classical APC accounting model has been resolved by the specification of the quadratic function for the age effects (Yang and Land 2006, p. 84)

An HAPC framework does not incur the identification problem because the three effects are not assumed to be linear and additive at the same level of analysis (Yang and Land 2013, p. 191)

This contextual approach … helps to deal with (actually completely avoids) the identification problem (Yang and Land 2013, p. 71)

Unfortunately, Yang and Land are misguided in their belief in the HAPC model to do the logically impossible, as simulation studies have shown (Bell and Jones 2014a; Luo and Hodges 2013). Yang and Land’s model can, and has, produced profoundly misleading results. For example, consider Reither, Hauser and Yang’s APC study of obesity in the USA (Reither et al. 2009). They used the HAPC model to find that the recent obesity epidemic is primarily the result of period effects. However, simulations that we conducted (Bell and Jones 2014b) showed that these results could have been found when cohorts rather than periods were behind the increase in obesity. This is shown in Fig. 10.2 – data generated by us with a large cohort effect and no period trend (column 1) produced results suggesting erroneously that period effects were more important (column 2), in line with the results found by Reither et al. (column 3). The difference between these two possible sets of results are important from a policy perspective – a significant cohort trend would suggest that interventions should be targeted at young people in their formative years, whereas a period trend would suggest that interventions would be worthwhile for individuals at all stages of the life course. Additionally, the life course (age) effect found by Reither et al. differed significantly from that proffered by the simulations (row 1 of Fig. 10.2). Once again, failing to appropriately model period and cohort effects can have a big effect on the found life course effect, and vice versa.

(Column 1) The true data generating process (DGP) of simulated datasets; (column 2) the results from applying the HAPC model to those simulated datasets; and (column 3) the results found by Reither et al. (2009), for the age, period and cohort effects (rows 1, 2 and 3 respectively) (This figure is adapted from figure 1 in Bell and Jones (2014b))

How to Model APC Effects Robustly

Whilst the HAPC model does not work as its authors intended, it does offer a compelling conceptual framework which is useful looking forward to ways one might model age, period and cohort effects together in a single model without falling foul of the identification problem. We have argued from the beginning that discerning APC effects mechanically is impossible. However, if we are willing to make certain assumptions about the nature of those APC effects, then inference is possible, and the HAPC model provides us with a useful framework in which to do so.

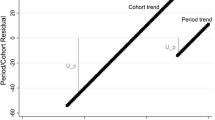

These assumptions need to be strong: for example one of the APC trends is often constrained to a certain value. The easiest way to do this is to constrain one of the period and cohort linear trends to zero by including the other as a linear fixed effect. For example, we may be willing to assume that there is no linear period trend, and include a linear cohort fixed effectFootnote 4 in the model. Thus, Eq. 10.5 is extended to:

We do not need to assume that there is no variation between periods in this model – indeed the period residual term \( {u}_{2j_2} \) remains in the model meaning periods (and cohorts) can still have contextual effects. However, we do assume that there is no linear trend over time in the true period residuals, because these will be absorbed by the age and cohort effects in this model.Footnote 5 If this assumption is justified, such a model will produce correct inference both about the linear age and cohort trends, and about the period and cohort random deviations from those trends (Bell and Jones 2014a). We would argue that often constraining the period trend to zero is a reasonable course of action. For us, the mechanism for long-run change is more easily conceptualised through cohorts than periods – change occurring by influencing people in their formative years rather than ‘something in the air’ that influences all age groups equally and simultaneously. However, this is of course dependent on the research question and subject area, and the researchers own understanding of the process at hand.

Having made the above assumption, and thus (assuming the assumption is valid) dealt with the identification problem, the model can now be extended in a number of ways. First, using the multilevel framework, additional levels can be added to fit the structure of the data being used. The HAPC model was originally designed for repeated cross-sectional data (such as the ONS Longitudinal Study (Office of National Statistics 2008)), where a cross-sectional sample of individuals is measured on multiple occasions, but individuals are not followed through time across these occasions. Where panel data (such as the BHPS) is used, that is data that does follow individuals over time, an individual level should be included to account for dependency within individuals between occasions. For other data designs, the HAPC model does not work so well: cross-sectional studies control for periods by design, but therefore cannot differentiate between age and cohort effects; whilst single cohort studies (such as the Millennium Cohort Study (Hansen 2014)) control for cohorts by design but cannot differentiate age and period effects.

In our example that follows, we use the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) data (Taylor et al. 2010). Being a panel study, it follows individuals through time (in comparison to repeated cross-sectional data which selects a new sample with every wave), meaning that an individual level is necessary to account for dependency within individuals with occasions seen as nested within individuals. The BHPS also contains spatial identifiers (in this case, local authority and household variables), which could also help predict the dependent variable. Given this, it seems appropriate to extend the three-level structure outlined in Fig. 10.1 to a six-level structure shown in Fig. 10.3. Of course it may be found that one or more of these levels are not necessary and can thus be removed, but if all six levels were to prove significant, it would be important to include all of them to fully account for the dependency in the data and to assess the importance of individuals spatial, as well as temporal, contexts. It is certainly important to do this if one has potential predictors measured at a particular level.

An extension of the multilevel structure of the HAPC, for use with panel data and to incorporate spatial hierarchies. Thus measurement occasions are nested within individuals, which are themselves nested within cohort groups; measurement occasions are also nested into periods and households, the latter of which is additionally nested within local authority districts

Another extension would be to include an interaction between the age and cohort variable in the fixed part of the model. This is particularly useful for panel data, which effectively takes the form of an accelerated longitudinal design (for example see Freitas and Jones 2012). The age-by-cohort interaction allows for the possibility that the life course effect varies by generation – i.e. that there is not a single life course pattern that applies across all cohorts. In our view it is not appropriate to interpret this interaction as a period effect as others have done – for examples see Bell and Jones (2014c); the model still assumes that period effects are absent. The presence of an age-by-cohort interaction term is often thought of as a threat to inference about the life course, that is, a problem that needs to be corrected for (Miyazaki and Raudenbush 2000). However it seems to us that the interaction term can itself be of substantive interest, in understanding how life course trajectories have changed with changing cohort groups. Such an approach is increasingly common in the social medical sciences (Yang 2007; Shaw et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2010; Yang and Lee 2009), and in sociology more generally (McCulloch 2014). However, such designs are usually not combined with the cross-classified structure that characterises the HAPC model.

The model can be further elaborated by adding covariates at any level, or by allowing the effect of variables to vary at certain levels. For example, one could allow the life course (age) effects to vary between individuals, as is regularly done in simpler multilevel life course studies. One could also include control variables of various types, and interact these with the age and cohort variables to test whether the effects of these variables is constant over various dimensions of time.

The next section of this chapter puts this methodology into practice using the BHPS data to consider the life course and longitudinal effects on mental health.

Example: APC Effects on Mental Health with the BHPS

This exampleFootnote 6 uses data from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) to consider the age, period and cohort effects on mental health. The BHPS surveyed individuals from approximately 5,000 households (around ~10,000 individuals) from across the United Kingdom (UK), every year between 1991 and 2008 (Taylor et al. 2010). These individuals are measured on a wide range of social, demographic, economic and medical characteristics. Here, our outcome of interest is mental health and to that end, we use the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) (Goldberg 1972) to form our dependent variable. For the GHQ, respondents are asked 12 questions, and asked how far they agree with those questions on a four point scale. Each question is thus assigned a score from 0 to 3 on that scale, which are summed to create a single 36 point scale which can be treated as a continuous variable.Footnote 7 It is argued that the GHQ is a measure of psychiatric illness, both in terms of the severity of that illness, or as a probability of that individual being a psychiatric case (Goldberg and Williams 1988; Weich and Lewis 1998, p. 9), with high scores indicating a higher degree of psychiatric disorder. It should also be noted, however, that the GHQ is “sensitive to recent change in psychological well-being” (Weich and Lewis 1998, p. 12) and “transient disorders, which may remit without treatment” (Goldberg and Williams 1988, p. 5), and as such also encompasses a subjective understanding of mental health that complicates an understanding of individuals being ‘cases’ or ‘non-cases’.

In analysing this data, we first construct a 2-level multilevel model (with occasions nested within individuals). In this framework, age and cohort linear effects are included in the model as polynomials up to the cubic, with the highest powered terms removed when they were found to be non-significant. Here, we found evidence of a cubic age effect and a quadratic cohort effect. Next, we added a gender effect, and interactions between that and the linear age and cohort terms. We also added an interaction between the age and cohort linear terms (model 1 in Table 10.1).

Having established the significance of terms in the fixed part of the model, we then built up the random part of the model, to create the cross-classified structure portrayed in Fig. 10.3. A single level was added at a time, with the significance of that term assessed on the basis of a reduction in the Deviance Information Criterion (DIC) (Spiegelhalter et al. 2002). Our dataset contains 405 local authorities, 113,907 household years,Footnote 8 18 years, nineteen 5-year cohort groups,Footnote 9 25,889 people and 194,217 measured occasions, which form the structure of the random part of our models. In this case, it was found that all 6 levels were significant (the variances at these levels are different from zero) and were retained in the model (model 2 in Table 10.1). Finally we tested whether there were differential effects in the age effect between individuals, by allowing the linear age effect to vary at the person level; we also tested whether the random cohort variation was different for different genders, by allowing the gender effect to vary at the cohort level. We found the former to be significant and the latter insignificant (see model 3).Footnote 10

The results from three models – a two-level model, and two six-level models (one with random intercepts only and one with random slopes at the individual level on the age coefficient) – can be found in Table 10.1. As can be seen, model 1 (the two-level model) shows evidence of a significant age-cohort interaction with a negative coefficient estimate; this suggests that the life course effect is larger for earlier cohorts than for later cohorts. However this became insignificant when new levels were added to the model, and so in models 2 and 3 this term was removed.

Figure 10.4 shows the combined age and cohort effects on the GHQ score, based on the fixed part estimates of model 2. The cubic shape of the life course trend is clear, with an increase in GHQ score in young adulthood and in old age, but relatively stable GHQ score for the middle aged on average. The quadratic nature of the cohort effect can also be seen – more recent birth cohorts appear to report a worse level of mental health, but this effect is particularly pronounced (the lines are further apart amongst the earlier cohorts). However, in spite of its aesthetic advantages, this graph is actually quite difficult to read, especially in the presence of age-by-cohort interactions – it recombines the age and cohort effects that the model is aiming to pull apart and it is difficult to tell whether, for example, the 1980 cohort are of better health because they are younger or because they were born later. As such, Figs. 10.5 and 10.6 are somewhat more insightful – these graphs show the conditional effects of age and cohort respectively, that is the effect with the other variable kept constant. Additionally, for these graphs we have separated the results by gender (utilising the gender-by-age and gender-by-cohort interactions in the model), and, in the case of Fig. 10.6, incorporated the random variation from the cohort level variance into the graph. As can be seen in Fig. 10.5, the male and female age trends are approximately parallel – that is, whilst women in general report a higher GHQ than men on average, this difference does not change through the life course (this can also be seen by the insignificant age-by-gender interaction coefficient estimate in model 2). In contrast, there are quite different cohort trajectories for men and women, with cohorts mattering more for women, and the gender gap in health being greater for more recent cohorts (Fig. 10.6). In other words, there is a general trend of recent cohorts being less psychiatrically healthy (or, at least, reporting lower levels of psychiatric health), and this is especially the case for women. Additionally, we can see that there were certain cohort groups in which individuals are in general more healthy than the general quadratic trend would suggest – the statistically significant ones (at the 95 % level) are the cohort groups 1930–1934, 1965–1969 and 1970–1974. This is an interesting finding – that, compared to the overall cohort trajectory, people born in these cohort groups are healthier – especially given that the groups fall onto two of the biggest economic recessions of the twentieth century in the UK. The suggestion of this is that, in the long run, being brought up during a recession is good for your mental health. It is worth bearing in mind, however, that these effects are relatively small compared to the overall cohort effect. We additionally tested to see if this between-cohort variation was different for males and females, but doing so did not improve the model; in other words there are no significant differences between men and women in the deviations from the fixed effect quadratic cohort trend.

Figure 10.7 shows the period effects – that is, the period residuals estimated in the random part of the model. These effects are in general small, although some are statistically significant at the 95 % level: people were in general healthier than average in 1991 and 2003, and less healthy in 2000.

Finally, model 3 in Table 10.1 shows that allowing the age effect to vary at the person level improves the model fit substantially (the DIC declined by over 2500). People differ in their life course trends of their GHQ measure, and this is expressed by the person-level coverage intervalsFootnote 11 in Fig. 10.8. It can be seen that those with higher GHQ scores will experience a greater increase in GHQ scores over their lifetime than those with lower GHQ scores, and so the variance between individuals is greater amongst older people than younger people – this is a result of the positive covariance term (0.077) in model 3 of Table 10.1.

This model is for illustration only – one would normally add additional time varying and time invariant control variables (for example employment status, social position, income, wealth and ethnicity) in an attempt to account for the unexplained variation in the random part of the model. One could also further extend the model in any of the other ways mentioned above. It is also worth noting that, whilst this model presented here uses a continuous outcome, other outcomes could be used with different link functions (for example, if you wanted to analyse a binary health outcome, a logit or probit version of this model could be used).

Conclusions

The aim of this chapter is to highlight the perils in modelling age, period and cohort effects, and to provide some ways in which these perils can be overcome in longitudinal and life course research, in health and beyond. We have shown that researchers must put serious thought into which of age period and cohort they believe are behind changes that occur in society, and these must be appropriately specified in their model for accurate, policy-relevant inference to be made. We have highlighted a number of attempts to disentangle APC effects, and shown the shortcomings of these. Finally, we have presented a framework by which APC effects can be robustly measured, so long as certain assumptions (in our case the assumption of an absence of period trends) can be made. So long as this is the case, both long run polynomial trends and discrete random fluctuations can be modelled effectively, within a multilevel framework that can incorporate further variables and levels. We do not claim that our most complex model is always necessary (indeed in our example the simpler two-level model did a good job of accurately partitioning APC effects); however undoubtedly the extendibility of the model we present here is one of its strengths. Overall, we hope the chapter will encourage people to take the APC identification problem seriously and, when investigating life course and longitudinal effects, bear it in mind when constructing their statistical model.

Notes

- 1.

This and the subsequent section are adapted from Bell and Jones (2014a), section “The Age-Period-Cohort Identification Problem”.

- 2.

This section is in part adapted from Bell and Jones (2013).

- 3.

- 4.

Here we only include a linear cohort trend, but if we find it to be necessary we could additionally include polynomials, as we do in the subsequent example.

- 5.

Where we are unwilling to constrain a trend to zero, but are willing to constrain it to an alternative value, informative priors can be used in a Bayesian framework. See Bell and Jones (2015).

- 6.

This analysis is a simplified version of that done by Bell (2014), which engages in more detail in the substantive debates about mental health, and uses further control variables and interaction terms.

- 7.

The GHQ is often assessed as a dichotomous outcome, where each question is scored as a ‘case’ or ‘non-case’ and respondents who are cases for 3 or more questions are considered cases overall. However, as Goldberg (1972, p. 1) states, “the distribution of psychiatric symptoms in the general population does not correspond to a sharp dichotomy between ‘cases’ and ‘normals’. Psychiatric disturbance may be thought of as being evenly distributed throughout the population in varying degrees of severity.”

- 8.

The BHPS does not provide data on households that is linked across time – that is, households are conceptualised here as transitory, changing each year.

- 9.

Cohorts were grouped into 5-year intervals in the random part of the model, to account for the autocorrelation between cohort years. However, single year groups were used to define the fixed part cohort trends.

- 10.

All models were run using Bayesian Monte Carlo Markov Chain (MCMC) estimation using MLwiN version 2.29 (Rasbash et al. 2014; Browne 2009), with a 500 iteration burn-in and 50,000 iteration chain length. For hierarchical models, starting values were obtained from Iterative Generalised Least Sqaures (IGLS) estimation (Goldstein 1989), whilst for the cross-classified models (which cannot be estimated in IGLS in MLwiN) the previous model’s estimates were used as starting values, with small (relatively non informative) values used for any new parameters. To speed up convergence, hierarchical centering was used, which reduces the correlation between the parameter chains and so improves the mixing of the MCMC algorithms (Browne 2009, p. 401). All parameter chains were visually inspected for convergence, and the Effective Sample Size (ESS) was used to assess whether the model had been run for long enough. It was found that 50,000 iterations are sufficient to produce ESS scores of over 400 for all parameters. For practical advice on MCMC estimation see Jones and Subramanian (2013).

- 11.

Coverage intervals are not to be confused with confidence intervals. The latter gives the uncertainty around a parameter, the former gives the expected variation for the data.

References

Bell, A. (2014). Life course and cohort trajectories of mental health in the UK, 1991–2008 – a multilevel age-period-cohort analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 120, 21–30.

Bell, A., & Jones, K. (2013). The impossibility of separating age, period and cohort effects. Social Science & Medicine, 93, 163–165.

Bell, A., & Jones, K. (2014a). Another ‘futile quest’? A simulation study of Yang and Land’s hierarchical age-period-cohort model. Demographic Research, 30, 333–360.

Bell, A., & Jones, K. (2014b). Don’t birth cohorts matter? A commentary and simulation exercise on Reither, Hauser and Yang’s (2009) age-period-cohort study of obesity. Social Science & Medicine, 101, 176–180.

Bell, A., & Jones, K. (2014c). Current practice in the modelling of age, period and cohort effects with panel data: A commentary on Tawfik et al. (2012), Clarke et al (2009), and McCulloch (2012). Quality and Quantity, 48(4), 2089–2095.

Bell, A., & Jones, K. (2015). Bayesian informative priors with Yang and Land’s hierarchical age-period-cohort model. Quality and Quantity, 49(1), 255–266.

Browne, W. J. (2009). MCMC estimation in MLwiN, version 2.25. Bristol: University of Bristol: Centre for Multilevel Modelling.

Browne, W., Goldstein, H., & Rasbash, J. (2001). Multiple membership multiple classification (MMMC) models. Statistical Modelling, 1, 103–124.

Chen, F. N., Yang, Y., & Liu, G. Y. (2010). Social change and socioeconomic disparities in health over the life course in China: A cohort analysis. American Sociological Review, 75(1), 126–150.

Freitas, D., & Jones, K. (2012). Cohort change and individual development of aerobic performance during childhood: Results from the Madeira Growth Study. Under review.

Glenn, N. D. (1976). Cohort analysts futile quest: Statistical attempts to separate age, period and cohort effects. American Sociological Review, 41(5), 900–904.

Glenn, N. D. (2005). Cohort analysis (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Goldberg, D. (1972). The detection of psychiatric illness by questionnaire. London: Oxford University Press.

Goldberg, D., & Williams, P. (1988). A user’s guide to the general health questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-NELSON.

Goldstein, H. (1989). Restricted unbiased iterative generalized least-squares estimation. Biometrika, 76(3), 622–623.

Hansen, K. (2014). Millennium cohort study: A guide to the datasets. London: Institute of Education.

Jones, K., & Subramanian, S. V. (2013). Developing multilevel models for analysing contextuality, heterogeneity and change using MLwiN 2.2 (Vol. 1). Bristol: University of Bristol.

Luo, L. (2013). Assessing validity and application scope of the intrinsic estimator approach to the age-period-cohort problem. Demography, 50(6), 1945–1967.

Luo, L., & Hodges, J. (2013). The cross-classified age-period-cohort model as a constrained estimator. Under review.

Mason, K. O., Mason, W. M., Winsborough, H. H., & Poole, K. (1973). Some methodological issues in cohort analysis of archival data. American Sociological Review, 38(2), 242–258.

McCulloch, A. (2014). Cohort variations in the membership of voluntary organisations in Great Britain, 1991-2007. Sociology, 48(1), 167–185.

Miyazaki, Y., & Raudenbush, S. W. (2000). Tests for linkage of multiple cohorts in an accelerated longitudinal design. Psychological Methods, 5(1), 44–63.

Office of National Statistics. (2008). ONS longitudinal study 1971. UK Data Archive. Colchester: University of Essex.

Osmond, C., & Gardner, M. J. (1989). Age, period, and cohort models: Non-overlapping cohorts dont resolve the identification problem. American Journal of Epidemiology, 129(1), 31–35.

Page, A., Milner, A., Morrell, S., & Taylor, R. (2013). The role of under-employment and unemployment in recent birth cohort effects in Australian suicide. Social Science & Medicine, 93, 155–162.

Rasbash, J., Charlton, C., Browne, W. J., Healy, M., & Cameron, B. (2014). MLwiN version 2.30. Bristol: University of Bristol: Centre for Multilevel Modelling.

Reither, E. N., Hauser, R. M., & Yang, Y. (2009). Do birth cohorts matter? Age-period-cohort analyses of the obesity epidemic in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 69(10), 1439–1448.

Shaw, R. J., Green, M. J., Popham, F., & Benzeval, M. (2014). Differences in adiposity trajectories by birth cohort and childhood social class: Evidence from cohorts born in the 1930s, 1950s and 1970s in the west of Scotland. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, Online first. doi:10.1136/jech-2013-203551.

Spiegelhalter, D. J., Best, N. G., Carlin, B. R., & van der Linde, A. (2002). Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B: Statistical Methodology, 64, 583–616.

Suzuki, E. (2012). Time changes, so do people. Social Science & Medicine, 75, 452–456.

Taylor, M. F., Brice, J., Buck, N., & Prentice-Lane, E. (2010). British household panel survey user manual volume A. Colchester: University of Essex.

Weich, S., & Lewis, G. (1998). Material standard of living, social class, and the prevalence of the common mental disorders in Great Britain. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 52(1), 8–14.

Yang, Y. (2007). Is old age depressing? Growth trajectories and cohort variations in late-life depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(1), 16–32.

Yang, Y., & Land, K. C. (2006). A mixed models approach to the age-period-cohort analysis of repeated cross-section surveys, with an application to data on trends in verbal test scores. Sociological Methodology, 36, 75–97.

Yang, Y., & Land, K. C. (2013). Age-period-cohort analysis: New models, methods, and empirical applications. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Yang, Y., & Lee, L. C. (2009). Sex and race disparities in health: Cohort variations in life course patterns. Social Forces, 87(4), 2093–2124.

Yang, Y., Fu, W. J. J., & Land, K. C. (2004). A methodological comparison of age-period-cohort models: The intrinsic estimator and conventional generalized linear models. Sociological Methodology, 34, 75–110.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License, which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Copyright information

© 2015 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bell, A., Jones, K. (2015). Age, Period and Cohort Processes in Longitudinal and Life Course Analysis: A Multilevel Perspective. In: Burton-Jeangros, C., Cullati, S., Sacker, A., Blane, D. (eds) A Life Course Perspective on Health Trajectories and Transitions. Life Course Research and Social Policies, vol 4. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20484-0_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20484-0_10

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-20483-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-20484-0

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)