Abstract

On the one hand, this paper puts forward that the historical evolution of an n-word is conditioned by the presence or absence of a syntactic formal feature [uNeg]. Particularly, it shows that historically minimizers can either become Polarity Items or Emphatic Polarity Particles (with metalinguistic content) depending on their having an uninterpretable formal feature [uNeg] or not. On the other hand, it points out three different ways of fixing the syntactic expression of negation within natural languages—i.e. three different ways of licensing the [uNeg] formal feature: (1) under an unvalued [iNeg] Pol feature and either a Focus Operator that encodes the meaning [same]/[reverse], or a Force Operator that encodes [objection]; (2) under an anti-veridical operator Op¬ [iNeg]; and (3) under a non-veridical operator. Furthermore, the paper argues in favour of the significant role of syntax in the expression of metalinguistic negation. Hypotheses are tested through a syntactic and discursive characterization of three different types of Catalan negative expressions (pla/poc ‘no’, pas ‘not at all’, gens/gota/mica ‘any, none, nothing’) to show that their diachronic evolution, their distributional behaviour from a Romance comparative standpoint, and their licensing requirements fit perfectly. The contrast between two Old Catalan items with a similar origin, distribution and evolution (pas and gens), displays that pas had a formal [uNeg] feature licensed under a non-veridical or an anti-veridical operator in Old Catalan and, hence, it has evolved into a Negative Emphatic Polarity Particle (NEPP) with metalinguistic content in Modern Catalan, while gens did not and it has become a simple Polarity Item (PI). It is a well-known fact that Catalan pas conveys metalinguistic negation (that is, it intervenes in presupposition-denying contexts, descriptive semantic contradictions or other types of objections to a previous assertion), whereas gens does not. As for the loci of [uNeg] licensing, they are confirmed when tested through the Catalan and Italian data. First, it is shown that pas has undergone a change in its licensing conditions, so that Modern Catalan pas is licensed under anti-veridical operators (i.e., the negative marker no, which is underspecified as Op¬ [iNeg]). Second, Modern Catalan poc has an [uNeg] formal feature which is licensed under an unvalued [iNeg] Pol feature and a Focus Operator that acts as a probe for its movement to the Specifier of FocusP. And third, pla is licensed under an [iNeg] Pol feature and the relative polarity feature [objection] encoded in a ForceP Operator. Comparative data prove that Italian mica has an uninterpretable formal feature [uNeg] that can be licensed under two operators: First of all, under an [iNeg] Pol feature and a Focus Operator, in the same way as Modern Catalan poc. And, secondly, under an anti-veridical operator (Op¬ [iNeg]), like Modern Catalan pas.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

I leave aside (N)PIs that come from indefinites, such as ningú ‘nobody’ or res ‘nothing’. Many authors use the term PI (Vázquez-Rojas and Martín 2007; Labelle and Espinal 2013, 2014), where others use weak NPI (Batllori et al. 1998; Martins 2000) for negative expressions licensed under non-veridical operators. In this paper I am using PI as equivalent to weak NPI, and NPI as strong NPI. As for the licensing conditions of NPIs, see Horn (2016 this volume).

- 2.

Catalan poc and pla are dialectal: poc (‘no’) is used in the Northern Region of Catalonia (in the dioceses of Girona and Elne), and pla (‘yes’ and ‘no’), which is receding, is employed by adults and mostly within the generations of elder speakers of the North Oriental part. As for pas, it is common in Northern and Central varieties of Catalan, but its distributional position with reference to the verb restricts it to more limited areas: the configuration ‘Aux pas Participle’ (no l’he pas vist “I haven’t seen him at all”) is most frequently used in the Catalan spoken in Girona, l'Empordà and la Plana de Vic.

- 3.

See Batllori and Hernanz (2008, 2009, and above all 2013) for a detailed account of emphatic polarity particles and a specific explanation of the distinction between high and low particles in Catalan and Spanish. High negative emphatic polarity particles—HNEPP—are licensed in the left periphery, either in FocusP or in ForceP, whereas low negative emphatic polarity particles—LNEPP—are licensed within vP. Concerning high and low NEPP, see also Breitbarth et al. (2013).

- 4.

- 5.

That is, a metalinguistic negative meaning that contributes to implicatures, but not to truth-conditions. As for pragmatic activation in relation to Catalan pas, see Wallage (2016 this volume, Sect. 2.1).

- 6.

Notice that there is inter-speaker variation in the use of poc as an autonomous negative marker. Crucially, speakers from Girona and Figueres who are currently competent in its use seem to reanalyse poc as a negative marker that can be used out of the blue, without any cognitive effect. For more information on this, see Batllori and Rost (2013).

- 7.

Horn (2002: 77) quotes Yoshimura in relation to the meaning of metalinguistic or echoic negation, and mentions that it displays procedural rather than conceptual meaning, which explains its failure to license NPIs. If we take into account Escandell-Vidal and Leonetti (2000: 376) observation that there can be a systematic association between formal syntactic functional categories and the semantic notion of procedural meaning, the syntactic and cognitive traits of pas can be easily captured—see Sect. 5. Thus, pas can be regarded as a MN and, accordingly, its target “is what is not asserted”, what “is not part of explicit content and/or not communicated” (Horn 2002: 78–79). As for pla and poc, as suggested by Zeijlstra, NPIs would be licensed by Focus, rather than by these metalinguistic negators. This would explain why only HNEPPs license NPIs—see Footnote 3.

- 8.

This utterance would be grammatical in the Catalan spoken in the South of France (Conflent, Vallespir and Roussillon), in which pas is the negative marker.

- 9.

- 10.

Some Catalan varieties use ni mica instead of mica.

- 11.

Tubau (2008: 249–251) considers pas “a polarity item with underspecified polarity features”. I would rather say, however, that it is a NEPP with an uninterpretable formal feature [uNeg] that in some varieties (such as the one of Sant Ramon—Lleida) can still be licensed under a non-veridical operator, as it was in Old Catalan—see (15d).

- 12.

See Horn (2001: 452–456) for an inventory of NPI minimizers, and an account of the systematic use of indefinites to reinforce negation. Regarding the use of minimizers in Latin and their evolution to Romance PIs, see Batllori et al. (1998), Martins (2000). Horn (2010b: 111–148) gives a detailed account of multiple negation, a taxonomy of motives for double negation, and the factors intervening in this type of negation.

- 13.

- 14.

- 15.

As suggested by one of the anonymous reviewers, it is worth noticing here that, once mica and gota appear with intransitive verbs, we can say that they are no longer part of a nominal phrase.

- 16.

Old French pas displays several similarities with Old Catalan pas, as can be seen in Ingham (2014). The sequence pas ne is hardly ever attested in 13th century Old French prose works, but it is found in verse texts, especially in relative clauses. I would like to thank Professor Richard Ingham for this information, and also for the following example:

In my opinion, the comparative study of these items deserves further research. Unfortunately, a detailed account of this issue goes beyond the scope of this work.

- 17.

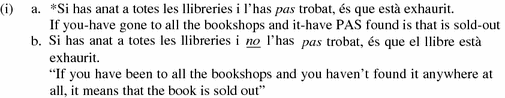

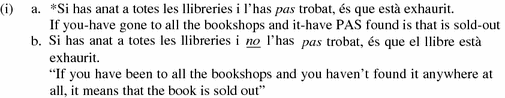

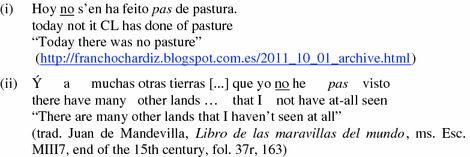

As illustrated below, this type of sentences would be ungrammatical in Modern Catalan without the negative marker no:

- 18.

Or even a negative marker (i.e., hypothesis IIIc): in fact, pas became the negative marker in the Catalan spoken near the French border (Alta Garrotxa and Alt Empordà) and the South of France (Conflent, Vallespir and Roussillon).

- 19.

As for the syntactic formal [uNeg] feature of pas in Old Catalan, it had to be syntactically licensed, at least, under non-veridicality, but it could also be licensed under anti-veridicality. In my view, this shows that Old Catalan pas was closer to a true or strict NPI than gens, mica and gota (which were PIs without a syntactic formal feature). However, eventually it did not evolve into an NPI, but into a NEPP with metalinguistic content.

- 20.

Notice that the terms Low Negative Emphatic Polarity Particle and High Negative Emphatic Polarity Particle refer to the syntactic representation of these items and the term Metalinguistic Negative Marker, which will be also used in Sect. 5, refers to the pragmatic meaning they convey.

- 21.

That is: “a metalinguistic use of the negative operator rather than […] a semantic operator which is part of logical form.”—see Horn (1985: 151).

- 22.

As for the syntactic structure and the hierarchical order of FocusP and PolP, see Haegeman (2000: 49). She argues that the landing site of neg-fronting in expressions like under no circumstances is not identical to that of the wh-preposing in under what circumstances, and also that FocusP should be reinterpreted in terms of an articulated structure containing two hierarchically organized positions: Focus Phrase and Polarity Phrase.

- 23.

This Focus Operator might encode the relative polarity features [same] and [reverse] (see Farkas and Bruce 2010).

- 24.

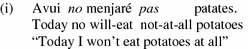

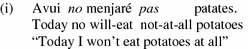

Catalan dialects display two instances of pas. In the Northern and Central areas of Catalonia pas is a NEPP:

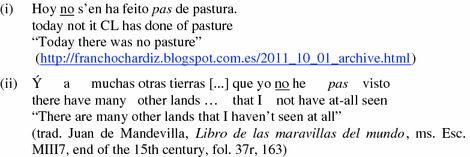

On the other hand, in the varieties spoken in Roussillon, Vallespir, and Conflent, as well as in some small villages of Alt Empordà and la Garrotxa, pas is the negative marker and, thus, it is used without no (like French pas):

Van Gelderen (2004, 2011) Negative Cycle accounts for this change: first, Late merged into the Spec of the NegP, and then Spec to Head reanalysis according to the Head Preference Principle.

- 25.

Aragonese pas displays a very similar behaviour to that of Catalan pas. Contrast the following examples with those given in (2) and (6).

I would like to thank Álvaro Octavio de Toledo for these examples and his accurate observations on Aragonese pas, which I leave aside for further research.

- 26.

As explained in Batllori and Hernanz (2008, 2009), Spanish quantitative poco is base generated in VP internal position, so that when it moves to PolP and to FocusP, its quantitive value is emphasized (and not the negative polarity of the sentence, as would be the case of Catalan poc). In this type of sentences there is obligatory adjacency between poco and the verb, and the subject occurs in postverbal position.

- 27.

The examples given by Cinque (1999: 4–11) are the following: Alle due, Gianni non ha solitamente mica mangiato, ancora “At two, G. has usually not eaten yet”. Non hanno mica già chiamato, che io sappia “They have not already telephoned, that I know”. Non hanno chiamato mica più, da llora “They haven’t telephoned not any longer, since then”. Da allora, non acetta mica più sempre i nostri inviti “Since then, he doesn’t any longer always accept our invitation”.

- 28.

Thanks to Professor Giuseppe Longobardi for the Italian examples. He speaks a Central Italian variety (Lazio) were the use of mica is perfectly productive.

- 29.

As defined by Horn (2001: 363), “metalinguistic negation focuses, not on the truth or falsity of a proposition, but on the assertability of an utterance.” It does not necessarily bring about the untruth of the equivalent affirmative proposition, and “can either be anchored in the previous utterance or deny a common ground presupposition” (Martins 2014). See Lee (2016 this volume) for additional information with regard to the way metalinguistic negation is processed.

- 30.

According to her, this feature [objection] “helps identify responding assertions, among declaratives”.

- 31.

Martins distinction between relative features encoded in the CP domain (i.e., [same], [reverse] and [objection]) and polarity features encoded in SigmaP (i.e., [+] and [−]) can be captured in my analysis under the assumption that the former are encoded either in ForceP or FocusP, and the latter in PolP.

- 32.

In regard to pas, in Modern Catalan it requires the presence of the negative marker no to be licensed, and cannot convey a negative meaning on its own. Espinal (1993: 355) already stated that in Modern Catalan it is no-pas that cancels a conceptual assumption, confirms someone’s expectations (i.e., a negative proposition or a conversational implicature), and reinforces negation. According to her, no-pas doesn’t contribute to the “explicit content of the proposition or to truth-conditions” and enriches “linguistically undetermined language expressions, by implying a non-descriptive use of negation” (Espinal 1993: 368). Thus, Modern Catalan no-pas is a Metalinguistic Negation Marker (MNM).

- 33.

Further evidence in favour of considering that the merge undergone by pas is morphological comes from the fact that neither an adverb nor a complement can interfere between pas and the auxiliary or the past participle, as illustrated in the following examples:

It is worth pointing out that the auxiliary and the participle constitute a morphological cluster in Modern Catalan.

- 34.

As a functional projection, TP conveys procedural meaning, and thus the impossibility of licensing (N)PIs follows.

- 35.

I would like to thank Professor Ian Roberts for this observation that I leave aside for subsequent research, because it is beyond the scope of this paper.

References

Baker, M. C. (2008). The syntax of agreement and concord. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Batllori, M., & Hernanz, M.-L. (2008). Emphatic polarity from latin to romance. Poster presented at the 10th Diachronic Generative Syntax Conference, August 7–9, 2008, Cornell University.

Batllori, M., & Hernanz, M.-L. (2009). En Torno a la polaridad enfática en español y en catalán: un estudio diacrónico y comparativo. In J. Rafel (Ed.), Diachronic linguistics (pp. 319–352). Girona: Documenta Universitaria.

Batllori, M., & Hernanz, M.-L. (2013). Emphatic polarity particles in Spanish and Catalan. Lingua, 128, 9–30.

Batllori, M., Pujol, I., & Sánchez-Lancis, C. (1998). Semántica y sintaxis de los términos negativos en su evolución diacrónica. Paper presented at the XXVIII Simposio de la Sociedad Española de Lingüística, December 14–18, Madrid.

Batllori, M., & Rost, A. (2013). Syntactic and Phonological evidence in favour of the grammaticalization of Northern Catalan negative poc/poca. Paper presented at the 21st International Conference on Historical Linguistics, August 8, Oslo.

Biberauer, T. (2013). Features, categories and parametric hierarchies: Unifying universality and diversity? Lecture at the Seminari del Centre de Lingüística Teòrica (CLT). October 25 2013, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Biberauer, T., Holmberg, A., Roberts, I., & Sheehan, M. (in press). Complexity in comparative syntax: The view from modern parametric theory. In F. Newmeyer & L. Preston (Eds.), Measuring linguistic complexity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Breitbarth, A., De Clercq, K., & Haegeman, L. (2013). The syntax of polarity emphasis. In A. Breitbarth, K. De Clercq & L. Haegeman (Eds.), Polarity emphasis: Distribution and locus of licensing. Lingua, 128, 1–8.

Chomsky, N. (1995). The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (2000). Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In R. Martin, D. Michaels, & J. Uriagereka (Eds.), Step by step: Minimalist essays in honor of Howard Lasnik (pp. 89–155). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cinque, G. (1976). Mica. Annali della Facoltà di Lettere e Filosofia dell’Università di Padova, 1: 101–112 [reprinted in Cinque, G. 1991. Teoria linguistica e sintassi italian (pp. 311–323). Bologna, Il Mulino].

Cinque, G. (1999). Adverbs and functional heads (pp. 4–11, 120–126). New York: Oxford University Press.

Escandell-Vidal, M. V., & Leonetti, M. (2000). Categorías funcionales y semántica procedimental. In M. Martínez, et al. (Eds.), Cien años de investigación semántica: De Michel Bréal a la actualidad, (Vol. 1, pp. 363–378). Madrid: Ed. Clásicas.

Espinal, M. T. (1993). The interpretation of no-pas in Catalan. Journal of Pragmatics, 19, 353–369.

Falcinelli, A. (2008). ‘Mica’ es fácil aprenderlo: instrucciones de uso del adverbio italiano. Culture, 21, 197–215.

Farkas, D. F., & Bruce, K. B. (2010). On reacting to assertions and polar questions. Journal of Semantics, 27(1), 81–118.

Fonseca-Greber, B. B. (2007). The emergence of emphatic ne in conversational Swiss French. Journal of French Language Studies, 17(3), 249–276.

Giannakidou, A. (2011). Negative and positive polarity items. In K. von Heusinger, C. Maienborn et al. (Eds.), Semantics. An international handbook of natural language meaning (Vol. 2, pp. 1660–1712). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Haegeman, L. (2000). Negative preposing, negative inversion, and the split CP. In L. R. Horn & Y. Kato (Eds.), Negation and polarity. Syntactic and semantic perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Haegeman, L. (2010a). The internal syntax of adverbial clauses. Lingua, 120, 628–648.

Haegeman, L. (2010b). The movement derivation of conditional clauses. Linguistic Inquiry, 41(4), 595–621.

Haegeman, L. (2013). The syntax of adverbial clauses. In S. R. Anderson, et al. (Eds.), L’Interface langage-cognition (pp. 135–156). Geneva: Librairie Droz.

Hansen, M.-B. M., & Visconti, J. (2009). On the diachrony of “reinforced” negation in French and Italian. In C. Rossari, C. Ricci, & A. Spiridon (Eds.), Grammaticalisation and pragmatics: Facts, approaches, theoretical issues (pp. 137–171). Bingley: Emerald.

Hernanz, M.-L. (2006). Emphatic polarity and C in Spanish. In L. Brugè (Ed.), Studies in Spanish syntax (pp. 105–150). Venezia: Cafoscarina.

Hernanz, M.-L. (2010). Assertive bien in Spanish and the left periphery. In P. Benincà & N. Munaro (Eds.), Mapping the left periphery. The cartography of syntactic structures (Vol. 5, pp. 19–62). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hoeksema, J. (2010). Dutch ENIG: From nonveridicality to downward entailment. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 28, 837–859.

Horn, L. R. (1985). Metalinguistic negation and pragmatic ambiguity. Language, 61(1), 121–174.

Horn, L. R. (2001). A natural history of negation. Stanford: CSLI.

Horn, L. R. (2002). Assertoric inertia and NPI licensing. CLS, 38, 55–82.

Horn, L. R. (Ed.). (2010a). The expression of negation. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Horn, L. R. (2010b). Multiple negation in English and other languages. In L. R. Horn (Ed.), The expression of negation (pp. 111–148). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Horn, L. R. (2016, this volume). Licensing NPIs: Some negative (and positive) results. In P. Larrivée & C. Lee (Eds.). Negation and polarity: Experimental perspectives (pp. 281–305), Cham: Springer.

Horn, L. R., & Kato, Y. (Eds.). (2000). Negation and polarity: Syntactic and semantic perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ingham, R. (2014). Old French negation, the Tobler/Mussafia law, and V2. Lingua, 147, 25–39.

Israel, M. (1996). Polarity sensitivity as lexical semantics. Linguistics and Philosophy, 19, 619–666.

Jäger, A. (2008). History of German negation. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Labelle, M., Espinal, M. T. (2013). Negative expressions and historical change in French. Lecture at the Seminari del Centre de Lingüística Teòrica (CLT). March 1, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

Labelle, M., & Espinal, M. T. (2014). Diachronic changes in negative expressions: The case of French. Lingua, 145, 194–225.

Larrivée, P. (2010). The pragmatic motifs of the Jespersen cycle: Default, activation, and the history of negation in French. Lingua, 120, 2240–2258.

Larrivée, P., & Lee, C. (Eds.). (2016). Negation and polarity: Experimental perspectives. Cham: Springer.

Lee, C. (2016, this volume). Metalinguistically negated versus descriptively negated adverbials: ERP and other evidence. In P. Larrivée & C. Lee (Eds.). Negation and polarity: Experimental perspective (pp. 229–255). Cham: Springer.

Lightfoot, D. W. (1991). How to set parameters: Arguments from language change. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Martins, A. M. (2000). Polarity items in Romance: Underspecification and lexical change. In S. Pintzuk, G. Tsoulas, & A. Warner (Eds.), Diachronic syntax. Models and mechanisms (pp. 191–219). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Martins, A. M. (2014). How much syntax is there in metalinguistic negation? Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 32, 635–672.

Meillet, A. (1912). L’évolution des formes grammaticales. Scientia, 12, 384–400.

Penka, D., & Zeijlstra, H. (2010). Negation and polarity: An introduction. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 28, 771–786.

Pfau, R. (2016, this volume). A featural approach to sign language negation. In P. Larrivée & C. Lee (Eds.). Negation and polarity: Experimental perspectives (pp. 45–74). Cham: Springer.

Rigau, G. (2004). El quantificador focal pla: un estudi de sintaxi dialectal. Caplletra, 36, 25–54.

Rigau, G. (2012). Mirative and focusing uses of the Catalan particle pla. In L. Brugé, A. Cardinaletti, G. Giusti, N. Munaro & C. Poletto (Eds.), Functional heads (pp. 92–102). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rizzi, L. (1997). The fine structure of the left periphery. In L. Haegeman (Ed.), Elements of grammar. Handbook in generative syntax (pp. 281–337). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Roberts, I. (2007). Diachronic syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Roberts, I., & Roussou, A. (2003). Syntactic change. A minimalist approach to grammaticalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rossich, A. (1996). Un tipus de frase negativa del nord-est català. Els Marges, 56, 109–115.

Rowlett, P. (1998). Sentential negation in French. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tubau, S. (2008). Negative concord in English and Romance: Syntax-morphology interface conditions on the expression of negation. Utrecht: LOT.

van der Auwera, J. (2010). On the diachrony of negation. In L.R. Horn (Ed.), The expression of negation (pp. 73–101). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Van Gelderen, E. (2004). Gramaticalization as economy. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Van Gelderen, E. (2011). The linguistic cycle. Language change and the language faculty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vázquez-Rojas, V., & Martín, J. (2007). Fragile equilibrium: (N)PI licensing in Catalan and Spanish. Ms.

Wallage, P. (2016, this volume). Identifying the role of pragmatic activation in the changes to the expression of English negation. In P. Larrivée & C. Lee (Eds.). Negation and polarity: Experimental perspectives (pp. 199–227). Cham: Springer.

Yoshimura, A. (2013). Descriptive/metalinguistic dichotomy? Toward a new taxonomy of negation. Journal of Pragmatics, 57, 39–56.

Zeijlstra, H. (2004). Sentential negation and negative concord. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Amsterdam.

Sources

[CTILC] Institut d’Estudis Catalans. Corpus Textual Informatitzat de la Llengua Catalana. http://ctilc.iec.cat/.

[DCVB] Alcover, A. M., & de Borja Moll, F. (2001–2002). Diccionari català-valencià-balear. IEC-Editorial Moll. http://dcvb.iecat.net/[Alcover, A. M., & de Borja Moll, F. (1930–1961). Diccionari català-valencià-balear: inventari lexical i etimològic de la llengua catalana. Moll, Palma de Mallorca].

[CICA] Directed by J. Torruella, with the collaboration of M. Pérez-Saldanya, & J. Martines. Corpus Informatitzat del Català Antic: http://www.cica.cat/.

Acknowledgments

Previous versions of this paper were presented at the XXVIIe Congrès International de linguistique et de philologie romanes (CNRS-Université de Lorraine, Nancy, France. July 15–20 2013), at the 19 e Congrès International des Linguistes (Université de Genève. 21–27 2013), at the Ibero-Romance Linguistics Seminar: Spanish and Catalan Linguistics Miniworkshop (University of Cambridge. Queen’s College. March 6th 2014), and at the Workshop on Negation (UAB. Barcelona. December 18th–19th 2014), whose audiences I thank for suggestions, comments, questions, and discussion. Thanks especially to Maria Teresa Espinal, Marie Labelle, Ian Roberts, Álvaro Octavio de Toledo and Ioanna Sitaridou for their suggestions, discussion and encouragement. I am especially grateful to Pierre Larrivée and Chungmin Lee, and to the five anonymous reviewers, whose observations and suggestions were very useful and contributed to considerably improve different aspects of this work. All errors are my own. This research has been supported by two grants from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (FFI2011-29440-C03-02) and (FFI2014-56968-C4-4-P).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Batllori, M. (2016). The Significance of Formal Features in Language Change Theory and the Evolution of Minimizers. In: Larrivée, P., Lee, C. (eds) Negation and Polarity: Experimental Perspectives. Language, Cognition, and Mind, vol 1. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17464-8_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-17464-8_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-17463-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-17464-8

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)