Abstract

Clients with impaired self-awareness following brain injury may benefit from an occupation-based approach to metacognitive training that uses real-life meaningful occupations in a supported therapy context. Metacognitive training in real-life contexts aims to improve clients’ intellectual awareness by demonstrating the impact of impairments on activities and participation, and thereby facilitate realistic collaborative goal setting and strategy use. Occupational performance provides familiar structured experiences that allow for the development of online awareness including error recognition and error correction. Training strategies include the use of self-prediction before occupational performance; self-monitoring and self-checking during performance; and self-evaluation, verbal or video feedback, and education following performance. The occupational therapist plays a supportive role and monitors the client’s emotional responses. A growing body of research evidence supports the use of occupation-based metacognitive training.

It wasn’t until the client watched the video of himself trying to cook dinner that he understood that he needed to use a checklist to keep on track.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abreu BC, Toglia JP (1987) Cognitive rehabilitation: a model for occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther 41:439–448

Barco PP, Crosson B, Bolesta MM, Werts D, Stout R (1991) Training awareness and compensation in postacute head injury rehabilitation. In: Kreutzer JS, Wehman PH (eds) Cognitive rehabilitation for persons with traumatic brain injury: a functional approach. Brookes, Baltimore, pp 129–146

Berquist TF, Jacket MP (1993) Programme methodology: awareness and goal setting with the traumatically brain injured. Brain Inj 7:275–282

Cheng SKW, Man DWK (2006) Management of impaired self-awareness in persons with traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 20(6):621–628. doi:10.1080/02699050600677196

Fleming JM, Ownsworth T (2006) A review of awareness interventions in brain injury rehabilitation. Neuropsychol Rehabil 16:474–500

Fleming JM, Lucas SE, Lightbody S (2006) Using occupational to facilitate self-awareness in people who have acquired brain injury: a pilot study. Can J Occup Ther 73:44–54

Goverover Y, Johnston MV, Toglia J, Deluca J, Goverover Y, Johnston MV, Deluca J et al (2007) Treatment to improve self-awareness in persons with acquired brain injury. Brain Inj 21(9):913–923

Katz N (2011) Cognition, occupation and participation. Across the lifespan. Neuroscience, neurorehabilitation and models of intervention in occupational therapy, 3rd edn. American Occupational Therapy Association, Bethesda

Katz N, Fleming J, Keren N, Lightbody S, Hartman-Maeir A (2002) Unawareness and/or denial of disability: implications for occupational therapy intervention. Can J Occup Ther 69:281–292

Klonoff PS, O’Brien KP, Prigatano GP, Chiapello DA, Cunningham M (1989) Cognitive retraining after traumatic brain injury and its role in facilitating awareness. J Head Trauma Rehabil 4:37–45

Landa-Gonzalez B (2001) Multicontextual occupational therapy intervention: a case study of traumatic brain injury. Occup Ther Int 8:49–62

Mateer CA (1999) The rehabilitation of executive disorders In: Stuss DT, Winocur G, Robertson IH (eds) Cognitive neurorehabilitation. Cambridge University Press, London, pp 314–332

Ownsworth T, Fleming J, Desbois J, Strong J, Kuipers P (2006) A metacognitive contextual intervention to enhance error awareness and functional outcome following traumatic brain injury: a single-case experimental design. J Int Neuropsychol Soc 12:54–63

Ownsworth T, Fleming J, Strong J, Radel M, Chan W, Clare L (2007) Awareness typologies, long-term emotional adjustment and psychosocial outcomes following acquired brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil 17:129–150

Ownsworth T, Fleming J, Shum D, Kuipers P, Strong J (2008) Comparison of individual, group and combined intervention formats in a randomized controlled trial for facilitating goal attainment and improving psychosocial function following acquired brain injury. J Rehabil Med 40:81–88

Schmidt J, Lannin NA, Fleming J, Ownsworth T (2011) A systematic review of feedback interventions for impaired self-awareness following brain injury. J Rehabil Med 43:673–680

Schmidt J, Fleming J, Ownsworth T, Lannin NA (2013) Video-feedback on functional task performance improves self-awareness after traumatic brain injury: a randomised controlled. Neurorehabil Neural Repair, Online access

Soderback I (1988) The effectiveness of training intellectual functions in adults with acquired brain injury: an evaluation of occupational therapy methods. Scand J Rehabil Med 20:47–56

Toglia J, Kirk U (2000) Understanding awareness deficits following brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation 15:57–70

Toglia JP (1998) A dynamic interactional model to cognitive rehabilitation. In: Katz N (ed) Cognition and occupation in rehabilitation. Cognitive models for intervention in occupational therapy. AOTA, Bethesda, pp 5–50

Toglia JP (2011) The dynamic interactional model of cognition in cognitive rehabilitation. In: Katz N (ed) Cognition, occupation and participation across the lifespan: neuroscience, neurorehabilitation and models of intervention in occupational therapy, 3rd edn. AOTA, Bethesda, pp 161–201

Unsworth C (1999) Cognitive and perceptual dysfunction: a clinical reasoning approach. Davis, Philadelphia

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

The Case Study of Linda Participating in Occupation-Based Metacognitive Training Using Video Feedback

Introduction

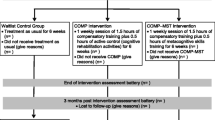

This case study concerns a participant in the randomized controlled trial of feedback interventions (Schmidt et al. 2013). Linda participated in the occupation-based metacognitive intervention and was assigned to the intervention group that received a combination of video and verbal feedback on her occupational performance . This group demonstrated the greatest treatment effects.

The student’s task includes

(1) reflection on the OT’s role, (2) discussion of intervention options, and (3) consideration of methods of evaluating intervention outcomes.

The following references are important to understand the measures used in the case study and to provide background knowledge for discussion:

Fleming JM, Ownsworth T (2006) A review of awareness interventions in brain injury rehabilitation. Neuropsychol Rehabil 16:474–500

Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF (1995) Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales, 2nd edn. Psychology Foundation, Sydney

Sherer M (2004) The awareness questionnaire. The center for outcome measurement in brain injury. http://www.tbims.org/combi/aq. Accessed 6 June 2008

Schmidt J, Fleming J, Ownsworth T, Lannin NA (2013) Video-feedback on functional task performance improves self-awareness after traumatic brain injury: a randomised controlled. Neurorehabil Neural Repair, Online access.

Teasdale G, Jennett B (1974) Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet 2:81–84

Toglia JP (2011) The dynamic interactional model of cognition in cognitive rehabilitation. In: Katz N (ed) Cognition, occupation and participation across the lifespan. Neuroscience, neurorehabilitation and models of intervention in occupational therapy, 3rd edn. AOTA, Bethesda, MD, pp 161–201

Overview of the Content

Aim

The aim is to reduce the number of cognitive errors made during meal preparation (online awareness) and to improve self-knowledge (intellectual awareness).

Learning Objectives

By the end of studying this case study, the learner will:

-

Understand the application of a metacognitive occupation-based intervention in brain injury rehabilitation

-

Appreciate the use of video feedback to improve self-awareness and functional performance in a client with severe brain injury

-

Learn examples of ways to monitor outcomes within a therapy intervention.

Background History of the Clinical Case Study

-

a.

Personal data: Linda was a 49-year-old inpatient in a brain injury rehabilitation unit. She sustained a traumatic brain injury from a fall down the stairs and was in the acute hospital for 2 months before admission to rehabilitation. Prior to the accident, she lived with her supportive husband and one adult child in a two-storey home in an urban area. Linda worked full time as a sales assistant and had a high-school-level education.

-

b.

Medical diagnosis: Linda’s Glasgow Coma Score (6 at the scene; Teasdale and Jennett 1974) and her length of posttraumatic amnesia (16 days) indicated a severe injury. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed a left subdural hemorrhage and a left occipitoparietal haematoma. Other injuries included a right temporal bone fracture, laceration to her forearm, and right facial nerve palsy. Functional impairments included right hemiparesis, reduced fine motor ability, and impaired balance. She had no relevant past medical history. Neuropsychological assessment indicated relatively intact global cognitive function with some areas of weakness including basic visual attention , planning, and organization. An occupational therapy functional assessment showed that Linda had impaired attention, memory, and judgment and displayed signs of impulsivity during various occupations.

Prior to intervention, the Awareness Questionnaire (AQ; Sherer 2004) was completed to determine Linda’s level of intellectual awareness (Table 30.1). The discrepancy between her self-rating and the therapist’s rating was positive at baseline indicating that she underestimated the extent of her brain-injury-related limitations. Linda completed the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21) to identify any symptoms of emotional distress (Lovibond and Lovibond 1995). Her scores were within normal limits (Table 30.1). Linda’s prognosis was largely unknown because outcomes from severe brain injury are highly variable. However, the cognitive impairments that Linda experienced tend to have a significant impact on psychosocial function in the domains of independent living, work, and interpersonal relationships.

-

c.

Internal and external environmental circumstances: As Linda was an inpatient, the intervention had to be conducted within the hospital environment not in a real-life environment. The occupational therapy kitchen was utilized to simulate a naturalistic environment for meal preparation. To increase the client-centeredness and meaningfulness of the activity, the therapist asked Linda to choose a meal from three options. She chose to prepare spaghetti bolognaise for dinner.

-

d.

Reasons for seeking occupational therapy consultation: Linda received occupational therapy as part of her multidisciplinary rehabilitation. She was invited and agreed to be involved in a clinical trial evaluating the effectiveness of feedback interventions (Schmidt et al. 2013). Linda was randomly allocated to the group that received a combination of video and verbal feedback.

-

e.

Occupational needs: Linda had goals to return home, be independent with daily tasks such as her self-care routine, prepare breakfast and lunch, and return to her recreation and leisure activities.

Questions Regarding Occupational Therapy Interventions

-

1.

What metacognitive techniques could the therapist use before, during, and after engagement in occupational performance to improve outcomes?

-

2.

What is the role of the OT in the intervention?

-

3.

How would you know if the intervention was effective?

-

4.

What alternative occupational therapy interventions are available?

Summary of the Results

The first step in the occupation-based metacognitive intervention involved Linda and her therapist establishing the steps and sequence of the task. A checklist of the steps was developed to provide a rating scale for self-evaluation. Linda then prepared the meal. The therapist provided appropriately timed prompts and feedback , using the “pause, prompt, praise” technique and videotaped Linda’s performance.

After each meal preparation session, Linda and the therapist independently rated her performance using the checklist they had developed. Then, Linda and the therapist watched the video of the meal preparation together. During the viewing, they identified errors or aspects of performance that could be improved on, effective use of compensatory strategies, and other areas of strength. They also discussed discrepancies in their ratings on the checklist.

Linda prepared the same meal and received feedback on four occasions over a 2-week period. The first time Linda made 34 errors that were corrected by the therapist. Errors included impaired judgment of when food was cooked, becoming distracted, inappropriate sequencing of steps, and impulsivity throughout the task. She took 40 min to prepare the meal and did not attempt to use any compensatory strategies. In subsequent sessions, the number of errors reduced to six errors during the last session (Fig. 30.1). She independently initiated effective strategies, which included marking which steps were completed, pausing prior to completing a step, and using self-talk. Her time use was more efficient, taking 25 min.

Linda completed the AQ and DASS-21 after the intervention (Table 30.1). The closer alignment of Linda’s and the therapist’s AQ ratings indicated that her intellectual awareness had improved. Postintervention scores on the DASS-21 were within normal limits and similar to baseline.

Linda also completed a follow-up session 8 weeks later which was conducted at her home after discharge. Generally, Linda maintained the gains in online awareness (ten errors) and continued to be efficient in meal preparation, taking 32 min. On the AQ, Linda continued to overestimate her abilities, but to a lesser degree than baseline. DASS-21 scores remained within normal limits (Table 30.1).

When asked about the experience of receiving video feedback, Linda reported that she found it “helpful to revise and review what I had done…. It helped me highlight things that I didn’t do correctly.” When asked what emotions she felt, she reported“I was very pleased with myself, as I had improved so much.” She reported that it was“not intrusive or bothersome to be recorded” to be videotaped and that she enjoyed making food and eating it.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Fleming, J., Schmidt, J. (2015). Metacognitive Occupation-Based Training in Traumatic Brain Injury. In: Söderback, I. (eds) International Handbook of Occupational Therapy Interventions. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08141-0_30

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08141-0_30

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-08140-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-08141-0

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)