Abstract

In the face of ontic (as opposed to epistemic) openness of the future, must there be exactly one continuation of the present that is what will happen? This essay argues that an affirmative answer, known as the doctrine of the Thin Red Line, is likely coherent but ontologically profligate in contrast to an Open Future doctrine that does not privilege any one future over others that are ontologically possible. In support of this claim I show how thought and talk about “the future” can be made intelligible from an Open Future perspective. In so doing I elaborate on the relation of speech act theory and the “scorekeeping model” of conversation, and argue as well that the Open Future perspective is neutral on the doctrine of modal realism.

I am grateful to participants at the, “What is Really Possible?” Workshop, University of Utrecht, June, 2012, for their comments on an earlier draft of this chapter. Research for this chapter was supported in part by Grant #0925975 from the National Science Foundation. Any opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Science Foundation.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Branching Time and Ontic Frugality

Our best current theory of the physical world implies that certain events occur in an irreducibly indeterministic way. For instance, if a radioactive atom decays, then its doing so is not the result of a prior sufficient physical condition. Instead, its decay is an irreducibly probabilistic process about which the most that can be said is that the atom’s decay was something very likely to occur within a certain interval of time. At no time, however, was its decay physically determined to occur. So too, on certain views about freedom of will, in some cases agents act or choose freely, and according to such views, this means that their free action or choice is not an event that had any prior, physical, sufficient condition.

On our best theory of the physical world, then, and on some views about free action or choice, there are points in time at which the future is ontologically open. This ontological openness is logically independent of epistemic openness. In many situations the future is epistemically open but ontologically closed. If the toss of a coin is a deterministic process, then how the coin will land may be epistemically open from the point of view of the person tossing it: she does not know whether it will come up heads or tails. By contrast, how the coin will land is not ontologically open. Things become more complicated when we ask whether the future can ever be epistemically closed but ontologically open. The atom’s decay is ontologically open: nothing in the current physics of the situation determines whether it will decay within the next hour. Might its decay nevertheless be epistemically closed? Might, that is, there still, at least in principle, be an omniscient being who knows what the future holds even when the future is not physically determined by the present? How we settle this question in turn depends on how we settle another. When the future is ontologically open, will it always nevertheless be the case that one of the potentially many possible continuations of affairs from the present is the one that is going to happen?

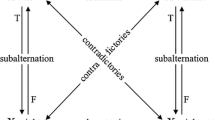

The view that in a situation of ontic openness, exactly one of the many possible continuations of affairs from the present is the one that is going to happen, has come to be known as the doctrine of the Thin Red Line (TRL). This usage originates with Belnap and Green (1994), who delineated the above characterization, offered an alternative view of the ontic status of the future in the face of ontic openness, and argued that the doctrine of the TRL is of dubious coherence. Belnap et al. (2001) develop these lines of thought in greater detail. However, in the two ensuing decades, innovative research on the semantics of tense and related topics has made it plausible that the TRL is, contrary to Belnap and Green, technically tractable (Øhrstrøm 2009; Malpass and Wawer 2012). A workable formal semantics for tensed statements, including those about “the future” can be developed that achieves various benchmarks for logical adequacy.

These developments do not, however, immediately settle all questions we may have about the adequacy of the TRL. For the TRL involves positing one—of many possible futures that are physically possible continuations from an earlier moment—as distinguished from those others as being what is going to happen. A more parsimonious view would treat all those physically possible continuations as on a par. Assuming that the former, TRL approach can be spelled out in a logically coherent way, we may still ask whether parsimony counsels against it. That will be our strategy below. Our question will not be whether the TRL is coherent, but whether it is justified by the ontological, semantic or other pertinent facts. More precisely, we will ask whether we can eschew the TRL doctrine while doing all we need to do in making sense of our talk and thought about time, the future, and the openness thereof. My argument will be that positing a TRL is coherent but unnecessary in making sense of talk and thought about the future, and that therefore parsimony enjoins us to eschew it.

2 Some Concepts from Speech Act Theory

Before proceeding it will be helpful to have on hand some concepts from the theory of speech acts.

2.1 Speech Acts Versus Acts of Speech

An act of speech is simply an act of uttering a word, phrase or sentence. One performs acts of speech while testing a microphone or rehearsing lines for a play. By contrast ‘speech act’ is a quasi-technical term referring to any act that can be performed by saying that one is doing so (Green 2013a). Promising, asserting, commanding and excommunicating are all speech acts; insulting, convincing, and winning are not. One can perform an act of speech without performing a speech act. One can also perform a speech act without performing an act of speech: imagine a society in which a marriage vow is taken by virtue of one person silently walking in three circles around another. Similarly, among Japanese gangsters known as Yakuza, cutting off a finger in front of a superior is a way of apologizing for an infraction. A sufficiently stoic gangster can issue an apology in this manner without making a sound. Also, speech acts can be performed by saying that one is doing so, but need not be. One can assert that the window is open by saying, “I assert that the window is open.” But one also can simply say, ‘The window is open,” and if one does so with the appropriate intentions and in the right context, one has still made an assertion.Footnote 1

Another feature distinguishing speech acts from acts of speech is that the former may be retracted but the latter may not be. I can take back an assertion, threat, promise, or conjecture, but I cannot take back an act of speech (Green 2013b). Of course, I cannot on Wednesday change the fact that on Tuesday I made a certain claim, promise, or threat. However, on Wednesday I can retract Tuesday’s claim with the result that I am no longer at risk of having been shown wrong, and no longer obliged to answer such challenges as, “How do you know?” This pattern recurs with other speech acts such as compliments, threats, warnings, questions, and objections. By contrast, with speech acts whose original felicitousness required uptake on the part of an addressee, subsequent retraction mandates that addressee’s cooperation. I cannot retract a bet with the house without the house’s cooperation, and I cannot take back a promise to Mary without her releasing me from the obligation that the promise incurred.

2.2 Saying Versus Asserting

In light of the speech act/act of speech distinction, it should also be plausible that one can say that P (for some indicative sentence P) without asserting P. One’s saying that P may not even be a speech act, as in the microphone case above. Or one might put forth P as a conjecture, guess, or supposition for the sake of argument instead of asserting P. All this would be too banal to merit mention were it not for the fact that some prominent authors have used these terms in idiosyncratic ways. For instance, Grice uses ‘say’ in such a way that one who says that P must also speaker mean that P. (This is why he treats ironical utterances (“Nice job!” said to a server who drops a bowl of calamari on my lap) as cases of making as if to say, rather than as cases of saying; otherwise Grice would fall in line with more common usage according to which the speaker said, “Nice job!” but meant something else (Grice 1989)).

2.3 Two Levels of Determination

An indicative sentence may, relative to a context of utterance, express a proposition, which in turn may be asserted. The first (syntactic) level underdetermines the second (semantic) level, which in turn underdetermines the third (pragmatic) level. How does the syntax of a sentence underdetermine its semantics? The sentence might be either lexically or structurally ambiguous. Even if a precise syntactic characterization resolves structural ambiguities (such as those found in ‘Every boy loves a girl.’) it will not disambiguate all ambiguous words. Furthermore, even an unambiguous sentence can fail to express a proposition in the absence of a context of utterance. ‘I am hungry,’ is not ambiguous, but only expresses a proposition in a context of utterance containing a speaker. (For other context-sensitive terms such as ‘here’, ‘now’, ‘recently’, and ‘you’, the context must also supply a location, a time, a past and an addressee, respectively.) Suppose then that ambiguity has been banished from our sentence and that a context of utterance has been supplied. We now have the sentence expressing a semantic content, but it will still not be determined whether it is being used in a speech act, assertoric or otherwise. For that, we would need to determine that the speaker is intending to commit herself in a certain way.

2.4 Assertion Proper and the Assertive Family

Assertion is only one of many speech acts aimed at conveying information. Keeping these other types of act in view will help us bring out assertion’s distinctive features. To help ensure clarity I will distinguish between the assertive family and assertion proper. The assertive family is that class of actions in which a speaker undertakes a certain commitment to the truth of a proposition. Examples are conjectures, assertions, presuppositions, presumptions and guesses. The type of commitment in question is known as word-to-world direction of fit. Members of the assertive family have word-to-world direction of fit, but we still do well to distinguish some of its members, such as conjectures, from assertion proper. We may begin to do so by noting that only assertion proper is expressive of belief. Were assertion not expressive of belief, it would not be absurd to assert, ‘P but I don’t believe it.’ By contrast, it is not absurd to say, ‘P but I don’t believe it’ when P is put forth as a guess, conjecture, or presupposition. These other members of the assertive family are thus not expressive of belief, although they may express other psychological states.

What is more, one who makes an assertion is open to the challenge, “How do you know?”, whereas this would not be an appropriate challenge to one who issues the same content with the force of a conjecture or a guess. Instead, an appropriate challenge to a conjecture would be to ask whether the speaker has any reason at all for her conjecture; another would be strong grounds for believing the conjecture to be incorrect. By contract, one can appropriately guess without having any reason for the guess at all. (To the challenge that there must be something that made the speaker guess one thing rather than something else, we may reply: such a cause need not be a reason.) Here again we see grounds for distinguishing assertion proper from the assertive family.

A more general pattern emerges upon inspection of Table 1:

The second and third columns describe what felicitous speech acts express, and in what way they express it. While all six speech acts considered here involve commitment to a propositional content, only two require belief for their sincerity condition. Guesses, presumptions, and suppositions require only acceptance for their sincerity condition sensu Stalnaker (1984); educated guesses can go either way.

3 Assertion and Scorekeeping

A good case can be made for the claim that an assertion is, at least in part, a proffered contribution to conversational common ground. Suppose we have a set S of interlocutors. Then S will have a common ground, \(\mathrm{{CG}}_\mathrm{{S}}\), which will be a (possibly empty) set of propositions that all members of S take to be true, and such that it is common knowledge that all members of S take them to be true. When a proposition \(\mathrm{{P}} \in \mathrm{{CG}}_\mathrm{{S}}\), speakers can felicitously presuppose P in their speech acts. For instance, if P is the proposition that Susan owns a zebra, then Frederick’s utterance of Susan is late for work today because her zebra is ill, will be felicitous. If P is not in \(\mathrm{{CG}}_\mathrm{{S}}\), then at best, Frederick’s utterance will update common ground only if his interlocutors accommodate him by adding P to \(\mathrm{{CG}}_\mathrm{{S}}\). Similarly, if \(\mathrm{{P}} \in \mathrm{{CG}}_\mathrm{{S}}\), then members of S can presuppose P in deliberating on courses of action.

Being a proffered contribution to conversational common ground is not, however, a sufficient condition for a speech act’s being an assertion. Other members of the assertive family meet this condition without being assertions: for instance, an educated guess is also characteristically a proffered contribution to conversational common ground, but is not to be confused with assertion proper. So too for conjectures and perhaps even suppositions for the sake of argument. In order to distinguish assertion proper from other members of the assertive family, we need to note that assertion has normative properties that other members of its family do not share. One making an assertion puts forth what she does as justified above a certain level. By contrast, one making an educated guess, or for that matter a sheer guess, puts that same content forth with a lower expectation of justification.

Assertions, conjectures, suggestions, guesses, presumptions and the like are cousins sharing the property of commitment to a propositional content. They also share the property of being used, characteristically, to contribute to conversational common ground. Yet these speech acts differ from one another in the norms by which they are governed, and thereby in the nature of the commitment they generate for those who produce them. An assertion (proper) puts forth a proposition as something for which the speaker has a high level of justification; by contrast, a guess might put forth a proposition as true but need not present it as having any justification at all. (Educated guesses, by contrast, seem to be closer to conjectures, which require a higher level of justification than do guesses, but not as high as do assertions.) Correspondingly, a speaker incurs a distinctive vulnerability for each such speech act–including a liability to a loss of credibility and, in some cases, a mandate to defend what she has said if appropriately challenged.Footnote 2

The development of common ground is typically only a means to other conversational ends. Many interlocutors work toward the development of common ground on their way to such larger aims as answering a question or forming a plan. In for instance an inquiry a group of speakers undertake to answer a question to which none of them has, or takes herself to have, an answer. Characteristically, such an inquiry is embarked upon as follows. One interlocutor may raise a question, and others may respond by accepting it as a worthwhile issue for investigation. (This is often marked by such replies as “Good question,” or more informally, “No idea; let’s figure it out.”) Once that has been done, the conversation now has a question Q on the table, and by definition has become an inquiry. Inquiries have distinctive norms. Participants in inquiries are to make assertions that are complete or, barring that, partial answers to the question on the table, and so long as no participant in the conversation demurs from those answers the interlocutors will make progress on their question. The level of informativeness required of inquirers flows from the content of the question on the table together with what progress has been made on that question thus far. If an inquiry has question Q on the table and thus far by offering and accepting assertions interlocutors have ruled out all but a few answers to Q, then all that remains is to determine which of the remaining answers is correct. Each interlocutor is to make assertions that will with the greatest efficiency, and in conjunction with the contents of common ground, rule out all but one of the answers that remain. Once that is done the question on the table will have been settled and this particular conversational task attained.

For those conversation that are also inquiries, then, a “scorekeeping” approach mandates keeping track not only of common ground, but of how its development moves interlocutors toward answering a question that is on the table.

4 Future-Directed Speech Acts

Assertions are not the only type of speech act that can raise questions about the reasonableness of talk of the future. We also conjecture, guess, suppose, and comport with other members of the assertive family while speaking of the future. As with assertion, so too with, say, conjectures: one might conjecture that the world’s oceans will rise by an inch by the end of the decade. Here, too, we want to be able to say that such a conjecture may well be justified even if we are aware that the future is sufficiently open to leave alive the ontic possibility that things will not go this way.

Sometimes assertions in the face of an ontically open future are reasonable. An example is a case in which there is a genuine but small chance of something occurring, such as a series of fifty consecutive heads on a fair but ultimately indeterministic coin. Perhaps I can assert reasonably that the coin will not come up heads on fifty consecutive tosses. On the other hand, imagine we are faced with what we know to be a fair coin, and consider the prospect of its being flipped. Here it is hard to see how it would be reasonable to assert that the coin will come up heads. It might be slightly more reasonable to conjecture that it will. By contrast one can easily see how it would be reasonable to guess that it will come up heads.

It is sometimes reasonable to make assertions about what we know to be an open aspect of the future. Such reasonableness can be accounted for by the fact that these assertions are well supported by currently available evidence. On the other hand, it can be reasonable to perform other acts within the assertive family about aspects of the future that are as likely to occur as not. Guesses about the tossing of a fair coin are a case in point. However, the reasonableness of such acts, be they assertions, guesses, conjectures, or suppositions for the sake of argument, does not have to be accounted for by appeal to a future that is privileged over all the others that are objectively possible. Instead, we may make sense of their reasonableness by adverting to the fact that it can be useful to commit oneself in such a way that what one says will turn out to be right or wrong depending on how things eventuate.

Why would it be useful to so commit oneself? There are at least two reasons. First of all, in so committing myself, I might enable us to answer a question that is on the table, and on that basis help us make a decision as to what to do. My prediction of tomorrow’s rain will, if accepted, help us to decide what to wear out of doors. On questions of less practical significance, I might still wish to commit myself for the purpose of burnishing my reputation in the event that what I say is borne out. Upon vindication I might proclaim, “See, I was right!” With enough such successes I might establish myself as an authority on a subject and reap the privileges that such a status affords. Predicting is in this respect like investing.

5 The Assertion Problem

In ‘Indeterminism and the Thin Red Line,’ Belnap and I described what we termed the Assertion Problem as an issue that needs to be faced by anyone who theorizes about thought and action directed toward an open future. The problem was as follows. It would seem that one can make assertions about what one knows to be an open future, and in particular about aspects of that open future that are not yet settled by what has transpired thus far. One can assert that the coin will land heads, knowing full well that, as we may now suppose, the coin-tossing process is a fundamentally indeterministic one. But in the absence of a TRL, it is difficult to see how we can provide truth values to such assertoric contents as ‘The coin will land heads’ when one history branching out of the moment of utterance contains a moment on which the coin lands head, and another history branching out of the moment of utterance contains a moment on which the coin lands tails. Were we to posit a TRL, then we could think of it as privileging one of these histories as the one that will happen, and thereby give us a state of affairs that settles the truth of the future-directed assertion. Barring that, it is not clear how we might characterize the context of utterance, or the circumstances of evaluation in such a way as to tell us whether the assertion is true. The context of utterance might provide values for indexical expressions, but it is less clear how the context of utterance selects one history from among all those that might be how things go.

The intuitive datum seems, then, to be twofold: one can (i) reasonably, and, (ii) felicitously, make an assertion about an aspect of the future that is ontically open and thus not settled by what has gone thus far.

The TRL approach has no difficulty making sense of this twofold datum. How can one do so when one abjures the TRL? In hopes of answering this question, let’s proceed more cautiously with our characterization of the data that need to be accounted for:

-

1.

Rational speakers make predictions about the future, and often with an awareness that the future is ontically open.

-

2.

Some of these predictions have the force of assertions, others the force of conjectures, while yet others have the force of other members of the assertive family.

-

3.

Some of the aforementioned acts would seem reasonable, as for instance when one guesses that the coin will come up heads.

-

4.

Some future-directed speech acts end up, in the fullness of time, being vindicated or impugned as the case may be.

In ITRL we considered an explanation of the above datum that supposes that all speech acts need for their evaluation to be relativized to a history. This history will then give a truth value for the content of the assertion, and thereby can help explain why such an assertion can be reasonable.

We also gave an account of future-directed speech acts in terms of liability to credit or blame. According to this view, an assertion that the coin will land heads is vindicated on those histories in which the coin lands heads; impugned on all other histories. This perspective is elegantly explained and motivated in Perloff and Belnap (2012).

Some authors have expressed dissatisfaction with the above “pragmatic” construal of assertion as a response to the assertion problem. Their core intuition seems to be as follows. Since an assertion on Tuesday about a future event on Wednesday can be fully formed—intelligible, felicitous, etc.—then the propositional content of that assertion must be “fully formed” as well, and thus that content must have a truth value at the time at which the assertion is made.

Thus baldly stated, the above reasoning rests on a fallacy of division that is easy to discern. However, while most authors will likely avoid such a fallacy, the conclusion of this reasoning seems to be seductive. For instance, Malpass and Wawer write,

To us, this move to pragmatics seems to be no help. We are concerned with the way that truth-values are given to predictions of future contingents in Priorian-Ockhamism. The basic problem is that utterances occupy single moments but many histories. Since we have to have both to ascribe a truth-value to a prediction (according to Priorian-Ockhamism), there are many non-trivial ways in which we can evaluate a given prediction. It can be true and false, at the same time, that there will be a sea battle tomorrow. Appealing to pragmatics is just to change the subject, in our opinion. It is as if Belnap et al. would have us consider the pragmatics of assertion involved in “a-asserts-‘The coin will land heads”’ while what we should actually be concerned with is the semantics of “The coin will land heads.” (Malpass and Wawer 2012, p.124)

This response presupposes something that we should call into question, namely that it is obligatory to give truth values to the propositional contents of predictions, and in particular truth values to those contents at the time at which the predictions are made. This, I contend, is not a datum forced upon us by any commonsense understanding of the practice of prediction. Rather, the intuitive datum that theorizing in this area must respect is that many predictions eventually are either borne out or not. This, however, is a datum that the Open Future view can accommodate. What is more, when we advert to the conversational role of predictions, we find that our pragmatic characterization of such acts is all we need. Without a settled truth value, predictions can still be entered into conversational common ground. Once that is done, the contents of such predictions can then be treated as true whether or not they currently have a truth value. For instance, my prediction among my fellow parched hikers that we will find water around the hill to the east, can be accepted as true whether or not it in fact is, and once so accepted we may act as if it is true by marching eastward.

This “pragmatic” solution to the assertion problem is compatible with the ascription of determinate content to future-directed speech acts. ‘The coin will land heads,’ has a determinate set of truth conditions, and as a result is different from ‘x is brindle’. So although, in the face of ontic openness, ‘The coin will land heads’ and ‘x is brindle’ are alike in lacking truth value, the former still has truth conditions that the latter lacks. This is why ‘The coin will land heads’ is an appropriate vehicle of assertion while ‘x is brindle’ is not. The point easily generalizes to other members of the assertive family, any of which can be used to make predictions about an ontically open future.

6 The Modal Realism Objection

Mastop (ms) objects to the Open Future view on different grounds from those having to do with future-directed speech acts. Mastop responds to remarks such as those found in Perloff and Belnap (2012) that the notion of indeterminism that they wish to explore is objective.Footnote 3 By this they mean that indeterminism is not a matter of our limited knowledge, or due to someone’s perspective on the world. Rather, the notion of indeterminism in question pertains to facts of the matter independent of anyone’s state of mind, interests, or point of view. In addition, the Open Future approach suggests that each of the possible futures flowing out of an indeterministic moment is ontologically speaking on a par with all the others: unlike what is the case on the TRL approach, no one history is privileged as against the others in any way.

Mastop seems to take these two doctrines as implying, jointly, that the Open Future view is committed to modal realism sensuLewis (2001). According to such a view, each possible future flowing out of an indeterministic moment is concrete but not spatiotemporally related to any other possible future. Mastop takes this modal realist view to be absurd, and infers that because the Open Future implies it, the Open Future view must be absurd as well. Instead, Mastop urges, we should adopt a modal metaphysics such as articulated by Stalnaker (2003), who sees possible worlds as “ways things might be.” This view is compatible with a TRL view, and Mastop take this fact to be evidence in favor of the TRL view.

We may remain neutral here on the question of the coherence of modal realism. What is more important is seeing that the Open Future view does not mandate it. Rather, Open Future is compatible with both modal realism and a “ways things might be” conception of possibilia. To see why, observe that the branches that are typically drawn in a tree diagram representing indeterminism are representations of how history might carry on after an indeterministic point. However, such branches need not be taken as representing states of affairs that are in any sense actual, even relative to themselves. By contrast, possible worlds on the modal realist construal are actual relative to themselves. (This is why it is natural for a modal realist to take ‘actually’ to be an indexical that refers to the possible world at which it is tokened.) Rather, it is compatible with Open Future to hold that such branches represent, “ways history might go.” Standing at an indeterministic point, then, we might say of each of the possible future courses of events, “This is a way that history might go; all we claim now is that none of these is what will happen.”

We have argued that the Open Future can make sense of the ontic status of possible futures, as well as of our thought and talk of the future even in the face of objective indeterminism. If this argument is sound, it will make clear that even if the TRL is a coherent position, it is unwarranted. It posits more than does Open Future, while providing no return for this higher cost. As a result we have no reason to accept the TRL, and every reason to maintain that, at least if our world is indeterministic, there will be moments in time at which the future is truly open.

Notes

- 1.

Failure to keep in view a distinction between speech acts and acts of speech can lead to mischief. For instance, R. Langton begins her ‘Speech acts and unspeakable acts’ (1993) as follows, “Pornography is speech. So the courts declared in judging it protected by the First Amendment. Pornography is a kind of act. So Catharine MacKinnon declared in arguing for laws against it. Put these together and we have: pornography is a kind of speech act.” Although Langton’s conclusion may be correct, the reasoning she uses to arrive at it is fallacious: the most that her premises establish is that pornography is an act of speech.

- 2.

This observation prompts a comparison between some speech acts and the phenomenon of handicaps as discussed in the evolutionary biology of communication. Green (2009) develops this analogy.

- 3.

“As affirmed in FF [Facing the Future], we require a concept of indeterminism that is local, objective, feature-independent, de re, existential, and hard” (Perloff and Belnap 2012, P. 584).

References

Belnap, N., and M. Green. 1994. Indeterminism and the thin red line. Philosophical Perspectives 8: 365–388.

Belnap, N., M. Perloff, and M. Xu. 2001. Facing the future: Agents and choices in our indeterministic world. New York: Oxford University Press.

Green, M. 2013a. Speech acts. The Stanford Online Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. by E. Zalta. http://www.plato.stanford.edu/entries/speech-acts/.

Green, M. 2013b. Assertions. In Handbook of pragmatics, Vol. II: Pragmatics of speech actions, eds. M. Sbisà, and K. Turner. Berlin: de Gruyter-Mouton.

Green, M. 2009. Speech acts, the handicap principle, and the expression of psychological states. Mind & Language 24(2009): 139–163.

Grice, P. 1989. Studies in the way of words. Cambridge: Harvard.

Langton, R. 1993. Speech acts and unspeakable acts. Philosophy and Public Affairs 22: 293–330.

Lewis, D. 2001. On the plurality of worlds. Oxford: Blackwell.

Malpass, A., and J. Wawer. 2012. A future for the thin red line. Synthese 188: 117–42.

Mastop, R. (ms). Truths about the future.

Øhrstrøm, P. 2009. In defence of the thin red line: A case for Ockhamism. Humana Mente 8: 17–32.

Perloff, M. and N. Belnap. 2012. Future contingents and the battle tomorrow. Review of Metaphysics 64: 581–602.

Stalnaker, R. 2003. Ways a world might be: Metaphysical and anti-metaphysical essays. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Stalnaker, R. 1984. Inquiry. Cambridge: MIT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

This chapter is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

Copyright information

© 2014 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Green, M. (2014). On Saying What Will Be. In: Müller, T. (eds) Nuel Belnap on Indeterminism and Free Action. Outstanding Contributions to Logic, vol 2. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01754-9_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01754-9_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-01753-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-01754-9

eBook Packages: Humanities, Social Sciences and LawPhilosophy and Religion (R0)