Abstract

Fragility fractures signal that osteoporosis or osteopenia may be present. These are fractures often sustained through minimal trauma and commonly happen because of a fall from standing height or less. Low bone density due to osteoporosis or osteopenia means that such falls easily result in fractures. Fragility fractures are common, and the incidence is increasing despite global efforts to improve access to secondary prevention. Fragility fractures can lead to hospitalisation, increased risk of death due to complications, worsening chronic health conditions, and frailty. Hip and vertebral fractures are associated with the worst morbidity, mortality, and loss of functional ability. Pain and disability contribute to impaired quality of life.

All people aged 50 years and over who sustain fragility fractures should, therefore, undergo investigation for osteoporosis and, if confirmed, be commenced on osteoporosis medication and be supported to participate in behaviours that are known to improve bone health. Organised and coordinated secondary fragility fracture prevention is the best option to prevent further fractures. This approach requires a multidisciplinary team working across care sectors in collaboration with the patient and family to ensure that care is consistent and person-centred and addresses individual need.

Many communities across the globe who sustain fragility fractures, however, do not have access to diagnosis and evidence-informed treatment to prevent the next fracture despite strong evidence that access to treatment and supportive follow-up prevent many subsequent fractures. This chapter aims to explore how secondary fractures can be prevented through evidence-based interventions and services.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

5.1 Introduction

Fragility fractures are sentinel events, signalling that osteoporosis or osteopenia may be present [1] as discussed in Chap. 2. These fractures are sustained through minimal trauma which most commonly, although not limited to, occur due to a fall from standing height or less [2]. Low bone density due to osteoporosis or osteopenia means that such falls easily result in fractures, even when the fall dynamics are relatively mild, as discussed in Chap. 4 [3]. According to the Global Burden of Disease study in 2019, fragility fractures are common and the incidence is increasing [4] despite the increase in global efforts to improve access to secondary prevention. The most common age groups susceptible to fragility fractures are people aged 50 years and over [5].

Fragility fractures are the leading cause of hospitalisation due to accidental injury with significant risk of death in the year following the fracture [6]. The increased risk of death is due to complications arising from immobility, surgery, worsening of comorbidities, and increased frailty. Of all types of fragility fractures, hip and vertebral fractures have the greatest impact on the individual and are associated with the worst morbidity, mortality, and loss of functional ability as a direct result of the fracture [7].

Even relatively minor fractures, such as those of the wrist, can lead to significant impairment and early mortality, independent of any contributing comorbidities. Pain associated with fractures, both at the acute and chronic stages, and resultant disability contribute to impaired quality of life for the person sustaining the fracture [8]. In a study of over 800 people, it was found that the effects of fractures can impair quality of life at the same rate as complications of diabetes [9]—a key point for funders as well as health professionals in determining the service their community needs.

With this background in mind, all people aged 50 years and over who sustain fragility fractures should undergo investigation for osteoporosis and, if confirmed, be commenced on osteoporosis medication and be supported to participate in conservative behaviours that are known to improve bone health [10].

Global evidence confirms that organised and coordinated secondary fragility fracture prevention is the best option to prevent further fractures in all populations [6, 11]. The coordinated approach requires a multidisciplinary team working across care sectors in collaboration with the patient and family to ensure that care is consistent and person-centred and addresses individual needs. The multidisciplinary team and care providers in local communities must work within an agreed approach that includes patient identification, assessment (including bone health, comorbidities, social and psychological needs), diagnosis, treatment regimens, and follow-up over time, ensuring that everyone receives the healthcare they need. Local teams agree collectively on how care will be delivered, that is, the local ‘model of care’.

Internationally, secondary fragility fracture prevention models have been in place for over 20 years and are commonly known as ‘fracture liaison services’ (FLSs) [12, 13] or sometimes ‘orthogeriatric fracture liaison services’ [14] and ‘(re)fracture prevention services’ [15]. Most are coordinated by a nurse or physiotherapist in collaboration with the multidisciplinary team [15, 16].

Despite the evidence for successful outcomes and cost-effectiveness [1, 17, 18], many people across the globe who sustain fragility fractures do not have access to diagnosis and evidence-informed treatment to prevent the next fracture [2, 19] despite the presence of the hallmark of a first or subsequent fragility fracture. Those with vertebral fractures are of special note as they often present ‘silently’ (asymptomatically) other than with back pain, which is often attributed to non-specific back pain. This further restricts access to appropriate care for this patient group [20].

There is strong evidence that access to treatment and supportive follow-up prevent at least 70% of refractures of vertebral fractures, 50% of hip fractures, and all other fragility fractures by 20–30% [21]. While the fundamental management of bone health is considered in Chap. 2, to help practitioners understand how they can support their patients’ efforts to prevent the next fracture, this chapter aims to explore how secondary fractures can be prevented through evidence-based interventions and services. An example of an ideal care pathway is provided in Box 5.1.

5.2 Learning Outcomes

At the end of this chapter and following further study, the nurse will be able to

-

Outline how secondary refracture prevention services can be developed, implemented, and evaluated.

-

Describe how to coordinate a multidisciplinary secondary fragility fracture prevention service.

-

Define the concepts included in an evidence-informed and effective secondary fracture prevention service including disease management, psychosocial needs, and self-management support strategies.

-

Explain the need for coordinated secondary fracture prevention through pathways and models of care such as fracture liaison services.

-

Discuss the role of practitioners in secondary fracture prevention and fracture liaison services.

Box 5.1 The Ideal Patient Journey Through Their Secondary Fragility Fracture Prevention Service

Mrs. Wang (aged 67 years) presented to her local hospital with her daughter, complaining of pain in her left wrist following a fall while working in her garden. She said that she was trying to get up from kneeling down and lost her balance. She had put her hand out to try and steady herself, which resulted in acute pain in her wrist.

Assessment in the emergency department (ED) confirmed a wrist fracture, which was immobilised with a back-slab. She was advised to attend the outpatient fracture clinic later that week. She was also advised to see her GP for further assessment of her antihypertensive medication as the ED doctor was concerned that she may have had a hypotensive episode precipitating her loss of balance.

The fracture liaison coordinator (FLC) visited Mrs. Wang in the ED. She introduced Mrs. Wang to the possibility that she may have osteoporosis, which predisposed her to fractures. She was told that if her bone had been healthy, she may not have had a fracture. Mrs. Wang agreed that she needed to know more so gave the FLC specialist nurse her contact details. They planned to discuss this further away from the ED when Mrs. Wang’s mind would be more receptive to understanding what they would discuss.

Mrs. Wang attended the outpatient fracture clinic, and it was decided to proceed to surgery to stabilise her fracture. Surgery was performed without complication the following day.

Two weeks later, she attended her appointment with the FLC where the FLC discussed with her how she was progressing since her surgery, especially regarding pain management, and whether she had visited her general practitioner (GP) for an update on care needs. She had seen her GP and so the discussion turned to why fragility fractures can occur and what she could do to improve her chances of not having another fracture.

Mrs. Wang also completed the fracture liaison service (FLS) patient-reported measure questionnaire and had a bone density scan in the department on the same day. While awaiting the bone density scan report, Mrs. Wang and the FLC discussed her patient-reported measure scores as it revealed that she reported social isolation since moving in with her family, away from previous friendships. It was agreed that she would link in with the local fall prevention team and support group. While Mrs. Wang was discussing her medication needs with the FLS doctor, the FLC made an appointment for her to be assessed by the team physiotherapist for the fall team.

The FLC phoned Mrs. Wang and her daughter a week later to see how she was progressing. By this time, Mrs. Wang and her daughter had done some online investigation as her neighbour had spoken about something she heard on the radio about the dangers of the medicines for osteoporosis. The FLC listened to their concerns and shared with them the evidence regarding osteonecrosis, especially regarding risk versus benefits of using the prescribed medication. The FLC also suggested that they speak to their GP to alleviate their fears. In the meantime, Mrs. Wang agreed to continue her medication.

Mrs. Wang confirmed that she had an appointment with the fall prevention team for the next week and was feeling positive about meeting other people of her age group and with some of the same health issues. She also agreed to complete the patient-reported measure questionnaire in a month’s time and post it back to the FLC. If no further issues were identified, they agreed that there was no need to contact each other again until this time next year when the FLS team would send her a questionnaire to address her current health status along with the patient-reported measure questionnaire. However, the FLC confirmed that Mrs. Wang and her daughter could contact the FLS team at any time if required.

5.3 Secondary Fracture Prevention

When a comprehensive FLS is in operation with participants being recruited from the age of 50 years and sustaining their first or subsequent fracture, the evidence is clear that FLSs can prevent many hip and other subsequent fractures.

This is the mantra of the FFN Secondary Fragility Fracture Prevention Special Interest Group. See https://fragilityfracturenetwork.org/secondary-fragility-fracture-prevention/.

Sustaining a fragility fracture is a signal that more fractures will occur, so healthcare that is known to prevent up to 70% of refractures must be instigated [21]. Unfortunately, healthcare systems across the globe often fail to provide this care because:

-

1.

No one professional group takes responsibility for identifying and treating this patient group.

-

2.

There are varying opinions by health professionals concerning who should be medically treated to prevent the next fracture.

-

3.

People with fragility fractures are not advised of their potential for having osteoporosis, so they never report this condition in population surveys; hence, the reported statistics for osteoporosis are erroneously low.

-

4.

Coding in health records is poor due to clinical teams not using terms in their medical records that inform the coder to report fragility fractures.

-

5.

There is a lack of available international diagnostic codes, even when a fragility fracture is identified.

This results in health systems being unaware of the need for action and failing to implement secondary prevention services that reduce refracture rates, improve the quality of life of those who sustain fragility fractures, and reduce the complications and mortality that are directly attributable to any fragility fracture, not just hip fractures [2].

It has been estimated that about 70–80% of people sustaining a fragility fracture do not gain access to secondary prevention care despite international evidence that reveals that ‘fracture liaison services’, as a successful systematic approach to secondary prevention, result in fewer refractures and significant cost savings for both society and health systems [22].

5.4 Development of Fracture Prevention Services and Best Practice

5.4.1 Models of Care

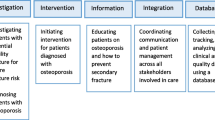

Several models of secondary fracture prevention services exist and are outlined in Table 5.1. Outcomes from different models of care vary. The more intensive the model of care, the better the bone health outcomes, along with improved quality of life, better use of resources, and cost-effectiveness [23]. Table 5.1 outlines what a meta-analysis revealed with varying intensities of intervention. Many services have reported their outcomes when using the type A model of care including Nakayama et al. [24], who reported on fragility fractures at their hospital, where an FLS had been in operation for over 10 years, compared to a hospital where there was no FLS. The study revealed that there were 40% less hip fracture presentations at their hospital compared to the site without FLS. This is just one example of findings much the same from FLS teams across the globe.

5.4.2 Value-Based Care

Value-based care (VBC) is a concept that is gaining momentum globally as a core way of revealing if a health intervention is worthwhile in terms of patient outcomes and value for investment [25, 26]. Incorporating patient-centred care in secondary fragility fracture prevention services will lead to outcomes that reflect VBC. While planning a service, or revising how an existing service is delivered, the elements of VBC should be at the front and centre of planning. The team decide which elements of the model of care are central including:

-

Deliver outcomes for patients that matter to them

-

Improve their healthcare experience

-

Improve health professional experience in their work

-

Make optimum use of the resources available to the team.

5.4.3 Patient-Centred Care

To achieve the elements of VBC, a service will need to include strategies that improve patient and family involvement in decisions. This will help their adherence to medical and conservative treatment and interventions. The decisions the patient and family make in collaboration with their service team will ensure that they are more likely to be receptive to their healthcare, resulting in better adherence to their agreed care plan.

Patient-centred care in a secondary fragility fracture service equates to being more attentive to what will

-

Enhance patient and family involvement (attendance)

-

Gain their full involvement in what needs to be done to reduce the risk of fracture and improve bone health (commence treatment)

-

Support the patient in working towards adherence to their mutually agreed treatment over time (care plan)

-

Help the patient and family understand the need for regular review of their treatment regimen to ensure that the strategy for improving and maintaining best possible bone health is appropriate for their needs over the long term.

5.4.4 Behaviour Change Strategies

Long-term and chronic healthcare teams have always realised the benefits of using behaviour change methods in achieving patient-centred needs [27,28,29]. This requires a change in mind-set from traditional care delivery. Teams need education and training and supportive managers to facilitate the incorporation of shared decision-making and listening more, both elements of behaviour change methodology. Patient-reported measures (PRMs) are also central as they elucidate many issues which concern individuals. Traditionally, services use PRM questionnaires for auditing quality improvement, but in behaviour change methods, they are also used in clinical assessment, care planning, and follow-up assessments [30].

Using behaviour change methods will help the care team to achieve patient engagement in their journey towards better bone health, which involves introducing the patient to their care plan. The journey to better bone health, in conjunction with other health issues the patient may have, can be onerous for the patient and family. Commencing too many health goals at one time can set them up to fail, so they need to understand the value of working on a small number of goals at one time. Helping them understand the need for medication to improve bone health is a priority; then one conservative goal of their choice can be added, later helping them determine further goals.

Working with the patient and family in this manner takes time, more than that required when the clinical team makes decisions for the patient which can overwhelm them and not give them time to determine the value of interventions. However, the positive and collaborative engagement of people who seek the care of a secondary fragility fracture prevention service will lead to enhancements of patient outcomes (less refractures due to adherence to evidence-informed therapies) [11] and improved use of health service resources (less presentations for further fractures) [17].

5.4.5 Fracture Liaison Services

As the fracture liaison service (FLS) model of care is the most widely implemented globally, the following descriptors of successful secondary fragility fracture prevention will refer to the FLS type of services, although local services may be called something different. Models of care need to be developed with consideration of local culture, circumstances, population structure, and resource allocation.

The FLS model of care was developed and evaluated by a team in Glasgow, Scotland, over 20 years ago [12]. Their model of care described the organised and coordinated team of health professionals who collaborate to ensure that people who sustain fragility fractures have access to diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up [10]. Over time, the Glasgow model evolved in the UK to include coordinated care across primary and secondary care environments [31].

Over the past 20 years, many services have added elements to meet their local requirements. Figure 5.1 outlines one way a local service has adapted the Glasgow model of care in New South Wales (NSW), Australia.

The NSW model of care for osteoporotic refracture prevention [15] (Reproduced with permission)

5.4.6 Location of Service

The location of a service will be a local decision based on local needs. While services have traditionally been hosted in a hospital setting, others have opted for community-based settings and telehealth options. Considerations to support the decision on location will include patient access, where the multidisciplinary team can be located, and where a suitable venue is available.

The COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged an emphasis on telehealth models of care. Despite previous concerns about these modes of delivery not being acceptable to many patients, necessity has now shown that they are both acceptable and effective [32]. The pandemic has also led to rethinking of how services, such as some elements of assessment, can be provided concurrently with other services such as fracture clinics [33]. As with all decisions regarding a service, it will be a team decision in consideration of all the identified local issues.

5.4.7 The Multidisciplinary Team

For optimal outcomes, secondary fragility fracture prevention services must be delivered within a multidisciplinary approach with all team members employing behaviour change methods to support patient-centred care [34, 35]. As described in Sect. 5.4.4, behaviour change approaches, no matter the theory applied, have been shown to facilitate improved uptake of self-management [36,37,38]. The multidisciplinary team commonly includes the following:

5.4.7.1 Fracture Liaison Coordinator

Whether based in primary or secondary care settings, for best outcomes, the service should be led by what is internationally referred to as the fracture liaison coordinator (FLC) [39]. This role is commonly fulfilled by a senior nurse or physiotherapist. Patient care is, however, a shared responsibility with the FLC acting as a leader, but not the sole provider of care.

Responsibilities of the FLC, in collaboration with other team members, include the following

-

Coordinating a steering group to guide the service initiation and development. Steering group membership will comprise representatives of the clinical team—medical, nursing, allied health, a patient (or family member) with experience of fragility fracture, and management and funding allocation representatives.

-

Facilitating the development and maintenance of clinical records for assessment, treatment, and outcomes.

-

Being the link between people who access the service, the multidisciplinary team, and the wider health service, especially community services. Facilitating and agreeing to formal communication processes and vital liaison with primary care physicians.

-

Leading the development, implementation, and evaluation of quality improvement initiatives to ensure ongoing service improvements.

-

Ensuring that PRMs considering experience and outcomes are included and reviewed regularly as a part of quality improvement activities.

-

Ensuring that key performance indicators (KPIs) are collaboratively developed by the team as a joint effort and regularly collating and reporting these to the manager, funder, and others.

-

Supporting team members in extending their knowledge in contemporary fracture prevention through self-study and education initiatives.

5.4.7.2 Clinical Lead

The FLC works closely with a medical practitioner who provides medical governance, undertakes medical assessment, and prescribes treatment. The medical practitioner will have a keen interest in secondary fragility fracture prevention and act as the champion of the service. They will champion the value of the service to encourage administrators to provide sufficient resources to conduct the service. The clinical lead will be trained in any of the following medical specialties, but not limited to orthopaedic surgery, primary care, or as a specialist physician in rheumatology, endocrinology, geriatrics, rehabilitation, or pain medicine. In some areas, nurse practitioners are increasingly being authorised to work within a designated scope of practice in tandem with medical officers to undertake some of the medical assessment and prescribing.

5.4.7.3 Allied Health Professionals

People who attend an FLS have a variety of clinical needs that are best addressed by allied health professionals (AHPs). These may include their fragility fracture prevention plan or comorbidities that can impact their health and well-being and impede their ability to work effectively on their bone health. Access to and ensuring that there is a close partnership with local fall prevention teams are essential (see Chap. 4). While not all AHPs will be available in all areas, the service plan will include how to access practitioners such as physiotherapists, dietitians, social workers, psychologists, and others. Being inventive may include linking with AHPs outside the local area, sometimes even in another country, and learning from each other to gain access to aspects of their expertise. This is one of the benefits of networking through organisations such as the Fragility Fracture Network (FFN) (www.fragilityfracturenetwork.org), which has a Special Interest Group (SIG) for secondary fragility fracture prevention whose prime aim is to link health professionals globally to learn from each other and hear how others implement the requirements of successful fracture prevention in their local settings. Membership of FFN is free at the above web address.

5.4.7.4 Administrative Support

Administrative officers, sometimes called clerical officers or clinical support officers, are ideally placed to undertake the non-clinical activities of the FLS. This enables clinical staff to be free of conducting clerical activities to create more time to undertake clinical work. Activities include formatting and sharing documents outlining service activities to others involved in patient care outside of the service such as the patient’s family doctor, fall prevention teams, and other allied health professionals. Administrative officers will also undertake duties such as supporting the clinical team in collating data, formatting data for submission, and ordering resources.

5.4.7.5 Team Members External to the FLS

The team approach will include other professionals external to the FLS. For example, collaboration between hospital staff and care providers such as physicians and fall prevention and radiology services is vital and the opposite when the FLS is set in primary care. Collaboration across care settings facilitates seamless care and continuity of education about bone health and comorbidities.

5.5 Resources to Guide Best Practice Service Provision

To support the implementation of services, the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) has developed ‘Capture the Fracture’, a best practice framework that defines essential elements of service delivery and evaluation [39]. This includes the following:

-

Processes are in place so that each person requiring secondary fragility fracture prevention is identified and recruited to the service.

-

The patient and family are provided with information so that they understand the need to improve their bone health and how this is achieved through their efforts in tandem with their healthcare team.

-

There is access to investigation of their bone health such as bone densitometry, serum blood testing, and any others required for individuals.

-

The person and their family understand precipitating factors that may make them susceptible to osteoporosis and further fractures.

-

There is local access to medical and other care such as fall prevention and exercise programmes.

-

Primary and secondary care teams collaborate to ensure person and family-centred care.

-

Each person is followed up regularly long-term to support adherence to treatment with periodical medical review to ensure that their treatment remains appropriate for them.

To complement this framework, in 2020, the IOF Capture the Fracture initiative and the Global Fragility Fracture Network (FFN) developed patient-level key performance indicators (KPIs) [40]. These are designed to follow the patient journey through their FLS experience and to be used to determine what strategies need to be instigated to improve patient outcomes and experiences. They are also designed to be used in reporting the progress of an FLS to managers and funders of the service. See Fig. 5.2.

IOF/NOF/FFN [40] patient focused key performance indicators for fracture liaison/prevention services

Other resources developed for global use are the FFN Clinical [41] and Policy [42] Toolkits where there is extensive guidance concerning the patient and health service needs across acute care, rehabilitation, and secondary fragility fracture prevention. They are available in several languages.

5.6 The Patient and Family Journey

5.6.1 Identifying the Patient Cohort

Identifying people who require the FLS is critical and can be the most time-consuming element. This patient group is often not recorded in medical records as having sustained a ‘fragility fracture’ but simply a ‘fracture’. Early in the development of a service, the local steering group will need to guide and support the FLC in setting up a system that aims to identify everyone requiring the service, not just those formally referred to it. An agreed hospital/health service policy will also be needed that states that all potential patients needing secondary fragility fracture prevention interventions will be automatically enrolled in the local service. Globally, some services have set up electronic identification systems that capture all those aged 50 years and over who present with a fragility fracture with some generating lists of eligible patients but also their complete health data. This will help determine where a person’s care should be provided; for example, a frail older person may be cared for in an orthogeriatric FLS, compared to the less complex patient in an FLS that caters for all other patients, and some may be best managed in their primary care setting. These ‘whole of health’ identification systems can also help provide information about patients before meeting them, including other chronic conditions or disabilities, and those who are already receiving fracture prevention medications, who may not need medical review but may still require self-management support with medication adherence and conservative care requirements.

International guidelines suggest that all people aged over 50 years who have sustained a fragility fracture, however they are identified, should be assessed [43]. For hospital-based services, therefore, the identification process needs to include the following settings:

-

Emergency departments (ED): whether admitted to a ward or discharged directly from the ED

-

Inpatients in all wards/units, including those who sustain a fracture while an inpatient

-

Radiology reporting, especially in the identification of vertebral fractures, whether incidental or anticipated

-

Outpatient clinics of any specialty

-

Those referred from primary care settings who had not attended ED or been admitted to a ward

5.6.2 First Contact with the Service

The first meeting may be within a hospital ward or department, or by telephone/online. An explanation of the reasons for referral is required, along with a discussion about the nature of fragility fracture and osteoporosis, investigations that are required, and potential results. These initial discussions should be brief and aim to help the person and/or their family know why the service is required for them. Further discussions can follow later after time to absorb initial information.

A further comprehensive meeting can be scheduled within 2 weeks when data from investigations may be available. At this appointment, the patient will complete the PRM form so that a baseline assessment can be discussed, with plans to revisit this at the next meeting.

5.6.3 Patient Assessment

There are several elements to patient assessment including the following

-

1.

Timing of assessment. After the initial assessment when the discussion centres on basic information about bone health and the opportunities to manage the risk of refracture, the next will include a more collaborative discussion as the person will have had time to consider and seek information. Myths can be dispelled with evidence to the contrary, and, using behaviour change methods, a plan of the next steps will be made.

-

2.

Incorporation of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). To engage the patient and their family, it is important to listen carefully to incorporate what they have to say and how they score themselves on a ‘whole of person’ PROM. This will include activities of daily living along with issues that align with having had a fracture, the potential for a chronic condition diagnosis, and for psychological effects of this diagnosis [44]. Psychological discomfort can impede engagement in the treatment and positive attitudes. The PROM and Quality of Life Instrument Database offer tools that consider generic items and those that consider diagnosis-specific items including those for people with osteoporosis under the Rheumatology table [45] (see https://www.qolid.org/proqolid/search__1/pathology_disease_pty_1925/).

-

3.

Risk of further fractures can be estimated using tools such as the WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX®) (https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp) or the Garvan fracture risk calculator (https://www.garvan.org.au/promotions/bone-fracture-risk/calculator/). These can be an opportunity to help people to engage with assessment and treatment but should be used as a guide only, and clinical expertise should be applied relating to the variables that could affect scores.

-

4.

Consideration of risk factors. Risk factors for fragility fracture can be primary (those that are non-modifiable) or secondary (can be modified). Most are listed in Box 5.2.

Box 5.2 Risk Factors for Osteoporosis and Fragility Fractures: Non-Modifiable and Modifiable

Non-modifiable risk factors | Modifiable risk factors |

|---|---|

Age | Alcohol use |

Female gender | Smoking |

Parents with a hip fracture | Low body mass index |

Previous fracture | Poor nutrition with low calcium intake |

Ethnicity | Vitamin D deficiency |

Post-menopause | Eating disorders |

Long-term glucocorticoid therapy | Oestrogen deficiency |

Rheumatoid arthritis | Falls |

Primary/secondary hypogonadism in men | Sedentary lifestyle |

-

5.

Assessment of bone and general health status. Assessment (Chaps. 2 and 6) is essential and involves discussion about the mechanism of the fragility fracture, comorbidities, and investigations needed. Routine investigations will include:

-

Bone densitometry to assess bone health

-

Serum blood tests to assess calcium, vitamin D, and function of organs such as the thyroid gland, and others that may add to the risk of osteoporosis and contraindicate some bone-sparing medications that may be used in the treatment of osteoporosis

-

5.6.4 Health Education

Health education is essential during all patient interactions with the aim of supporting the person and their family/carers, at a pace that suits their ability to understand and respond positively. The goal is to support self-management of all aspects of preventing the next fracture in a person-centred manner so that they can develop the understanding and skills needed. They need to take responsibility for conservative interventions and work effectively with their healthcare team to be proactive with prescribed medical therapies and attend periodical check-ups to ensure that their treatment remains contemporary and appropriate. All health education sessions are an opportunity to dispel myths about osteoporosis treatments with positive, accurate explanations.

These conversations, along with formal group education, support the person to live well with a chronic condition and require significant skill in positively engaging them while recognising that they may not be able to assimilate all information in one consultation. Health professionals engaged in this work should seek training in behaviour change strategies as described earlier in this chapter.

5.6.5 Establishing a Personal Plan

Following diagnosis, a personalised care plan needs to be agreed to, listing treatment elements and including how the person and the healthcare team will work together to achieve the care plan elements, including access to services. The person will set goals for their self-management plan, which will be reviewed at agreed time frames to ensure that they and their healthcare team are on track for success in preventing the next fracture.

A few small goals set at any one given time will be more achievable and set the person and their family up for success. Using behaviour change strategies will reinforce the need for reviews of progress and resetting of goals [46]. To achieve the elements of their individualised care plan, the healthcare team must include primary care providers. The general practitioner/family doctor/primary care physician will know the person and their family better due to a longer term relationship with them, so are able to advise on long-term planning and follow-up.

5.6.6 Assessments Over Time

While reassessments can be a time-consuming aspect of the patient journey, especially with many patients waiting to be seen in an FLS, it is an important aspect of the service from three perspectives:

-

1.

Supporting the individual in their efforts to maintain their treatment regimens and to review their agreed goals, to understand why and discuss if any of their goals have been abandoned, and to help the person reset and add goals

-

2.

To ensure that they are seeking regular (e.g. 6 monthly) reviews with their health team to ensure that their bone health regimen remains contemporary and appropriate for their needs

-

3.

To provide evidence of their health outcomes along with the opportunity to gain the information required to report the KPIs as displayed in Fig. 5.2

5.7 Evaluation of the FLS

Evaluation of the outcomes of an FLS has two key purposes from determining the FLS outcomes

-

1.

The data can be used to decide what quality improvement activities are required and to inform any changes to the agreed model of care.

-

2.

To inform managers and funders with data that will provide evidence for resourcing improvements and future developments.

All team members are responsible for ensuring that patient and service records are maintained in the agreed format and are complete. This is a key aspect of the service planning by the team. Leaving this to the FLC places undue workload on them as well as leads to increased work for team members, so it is essential to agree on how this will be done and make it part of the routine workflow.

Summary of Main Points for Learning

-

A range of system failings make it difficult to identify people with a fragility fracture, so there is a ‘care gap’ that results in many people being undiagnosed and not treated to support secondary fragility fracture prevention.

-

Secondary fracture prevention services, often known as fracture liaison services, aim to narrow this gap by assessing all those who present to health services with a fragility fracture, prescribing medical and conservative treatment that aims to improve bone density and prevent refracture in collaboration with the patient’s primary care team.

-

It is essential to provide secondary fracture prevention in a coordinated and multidisciplinary manner, with agreements between service settings in primary care and secondary care.

-

Multidisciplinary care teams require training in behaviour change methods to ensure that patients are included in all decisions concerning their within a ‘whole of person’ approach. This training seeks to move away from previous attitudes and actions of clinical teams of disease-specific and didactic interactions. With whole of person and inclusion of patient and family in partnership with the clinical team, every effort is made to achieve better health outcomes.

-

It is important to determine the multidisciplinary model of care to be applied locally with representation of those who have the lived experience of a fragility fracture and understand the local culture.

-

This chapter is written as a guide for local teams in their development, implementation, and evaluation of the model of care chosen by local team members.

-

Secondary fragility fracture prevention services can remain operational despite the COVID-19 pandemic. A good outcome of our efforts to deter being infected with the virus is our learnings on the acceptability of providing services via telecommunications and over the internet. While the evidence concerning efficacy is not in as yet, these options add to the opportunities for patient and family preferences that are congruent with behaviour change theoretical models [47].

5.8 Further Study

-

Identify the education needs of your team in relation to secondary fragility fracture prevention, and consider how these needs might be fulfilled.

-

Examples of education resources include:

-

(a)

FFN Toolkits that are available in a variety of languages:

The Clinical Toolkit is available at https://fragilityfracturenetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/ffnclinicaltoolkit_english_v1_web.pdf. The Policy Toolkit is available at https://fragilityfracturenetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/ffnpolicytoolkit_english_v1_web.pdf.

-

(b)

IOF Capture the Fracture best practice framework is available at https://www.capture-the-fracture.org/node/20 and associated tools.

-

(c)

UK NOS Fracture Prevention Practitioner e-learning is available at uk/for-health-professionals/professional-development/e-learning-and-training/fracture-prevention-practitioner-training/.

-

(d)

Local and national training programmes, especially those offered in behaviour change methodologies. These may be referred to as ‘health coaching’, ‘shared decision making’, ‘self-management support’, or other terminologies that may be used locally.

-

(a)

Assessing your own learning and performance needs regarding secondary fragility fracture prevention

-

Having read this chapter and undertaken further study, discuss the learning you have gained from this chapter and the book so far with your colleagues: identify and discuss how you, as a team, might improve local practice in secondary prevention of fragility fractures.

Finally … a challenge from the authors

The challenge now is for teams internationally to conduct innovative quality improvement projects on how they can build on the methods of providing secondary fragility fracture prevention as described in this chapter. What can be done better in terms of value-based care to:

-

Keep patients safe

-

Be effective in clinical outcomes

-

Enhance patient and health professional experiences

References

Beaupre LA, Lier D, Smith C, Evens L, Hanson HM, Juby AG et al (2020) A 3i hip fracture liaison service with nurse and physician co-management is cost-effective when implemented as a standard clinical program. Arch Osteoporos 15(1):113

Akesson KE, Ganda K, Deignan C, Oates MK, Volpert A, Brooks K et al (2022) Post-fracture care programs for prevention of subsequent fragility fractures: a literature assessment of current trends. Osteoporos Int 33:1659

Carey JJ, Chih-Hsing WP, Bergin D (2022) Risk assessment tools for osteoporosis and fractures in 2022. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 36:101775

Wu A-M et al (2021) Global, regional, and national burden of bone fractures in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Healthy Longev 2(9):e580–e592

Axelsson KF, Johansson H, Lundh D, Moller M, Lorentzon M (2020) Association between recurrent fracture risk and implementation of fracture liaison services in four Swedish hospitals: a cohort study. J Bone Miner Res 35:1216

Wu C-H, Tu S-T, Chang Y-F, Chan D-C, Chien J-T, Lin C-H, Singh S, Dasari M, Chen J-F, Tsai K-S (2018) Fracture liaison services improve outcomes of patients with osteoporosis-related fractures: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Bone 111:92–100

Chen W, Simpson JM, March LM, Blyth FM, Bliuc D, Tran T et al (2018) Comorbidities only account for a small proportion of excess mortality after fracture: a record linkage study of individual fracture types. J Bone Miner Res 33(5):795–802

Talevski J, Sanders KM, Vogrin S, Duque G, Beauchamp A, Seeman E et al (2021) Recovery of quality of life is associated with lower mortality 5-year post-fracture: the Australian arm of the International Costs and Utilities Related to Osteoporotic Fractures Study (AusICUROS). Arch Osteoporos 16(1):112

Voko Z, Gaspar K, Inotai A, Horvath C, Bors K, Speer G et al (2017) Osteoporotic fractures may impair life as much as the complications of diabetes. J Eval Clin Pract 23(6):1375–1380

Jones AR, Herath M, Ebeling PR, Teede H, Vincent AJ (2021) Models of care for osteoporosis: a systematic scoping review of efficacy and implementation characteristics. EClinicalMedicine 38:101022

Li N, Hiligsmann M, Boonen A, van Oostwaard MM, de Bot R, Wyers CE et al (2021) The impact of fracture liaison services on subsequent fractures and mortality: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 32(8):1517–1530

McLellan AR, Gallacher SJ, Fraser M, McQuillian C (2003) The fracture liaison service: success of a program for the evaluation and management of patients with osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 14(12):1028–1034

Akesson KE, McGuigan FEA (2021) Closing the osteoporosis care gap. Curr Osteoporos Rep 19(1):58–65

Naranjo A, Fernandez-Conde S, Ojeda S, Torres-Hernandez L, Hernandez-Carballo C, Bernardos I et al (2017) Preventing future fractures: effectiveness of an orthogeriatric fracture liaison service compared to an outpatient fracture liaison service and the standard management in patients with hip fracture. Arch Osteoporos 12(1):112

NSW Ministry of Health (2018) Model of care for osteoporotic refracture prevention. NSW Agency for Clinical Innovation, Chatswood

Royal Osteoporosis Society (2019) Effective secondary prevention of fragility fractures: clinical standards for fracture liaison services. Royal Osteoporosis Society, Camerton. https://theros.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/fracture-liaison-services/implementation-toolkit/

Major G, Ling R, Searles A, Niddrie F, Kelly A, Holliday E et al (2019) The costs of confronting osteoporosis: cost study of an Australian Fracture Liaison Service. JBMR Plus 3(1):56–63

Wu CH, Kao IJ, Hung WC, Lin SC, Liu HC, Hsieh MH, Bagga S, Achra M, Cheng TT, Yang RS (2018) Economic impact and cost-effectiveness of fracture liaison services: a systematic review of the literature. Osteoporos Int 29:1227–1242

Chesser TJS, Javaid MK, Mohsin Z, Pari C, Belluati A, Contini A et al (2022) Overview of fracture liaison services in the UK and Europe: standards, model of care, funding, and challenges. OTA Int 5(3 Suppl):e198

Lems WF, Paccou J, Zhang J, Fuggle NR, Chandran M, Harvey NC et al (2021) Vertebral fracture: epidemiology, impact and use of DXA vertebral fracture assessment in fracture liaison services. Osteoporos Int 32(3):399–411

Ganda K (2021) Fracture liaison services: past, present and future: editorial relating to: the impact of fracture liaison services on subsequent fractures and mortality: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 32(8):1461–1464

Curtis EM, Dennison EM, Cooper C, Harvey NC (2022) Osteoporosis in 2022: care gaps to screening and personalised medicine. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 36:101754

Ganda K, Puech M, Chen JS, Speerin R, Bleasel J, Center JR et al (2013) Models of care for the secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int 24(2):393–406

Nakayama A, Major G, Holliday E, Attia J, Bogduk N (2016) Evidence of effectiveness of a fracture liaison service to reduce the re-fracture rate. Osteoporos Int 27(3):873–879

Porter ME (2010) What is value in health care? N Engl J Med 363(26):2477–2481

Speerin R, Needs C, Chua J, Woodhouse LJ, Nordin M, McGlasson R et al (2020) Implementing models of care for musculoskeletal conditions in health systems to support value-based care. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 34:101548

Shi W, Ghisi GLM, Zhang L, Hyun K, Pakosh M, Gallagher R (2022) Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression to determine the effects of patient education on health behaviour change in adults diagnosed with coronary heart disease. J Clin Nurs 32:5300

Vallis M (2022) Behaviour change to promote diabetes outcomes: getting more from what we have through dissemination and scalability. Can J Diabetes 47:85

Bartlett SJ, De Leon E, Orbai AM, Haque UJ, Manno RL, Ruffing V et al (2020) Patient-reported outcomes in RA care improve patient communication, decision-making, satisfaction and confidence: qualitative results. Rheumatology (Oxford) 59(7):1662–1670

Rutherford C, Campbell R, Tinsley M, Speerin R, Soars L, Butcher A, King M (2020) Implementing patient-reported outcome measures into clinical practice across NSW: mixed methods evaluation of the first year. Appl Res Qual Life 16:1265

Fuggle NR, Kassim Javaid M, Fujita M, Halbout P, Dawson-Hughes B, Rizzoli R et al (2021) Fracture risk assessment and how to implement a Fracture Liaison Service. In: Falaschi P, Marsh D (eds) Orthogeriatrics: the management of older patients with fragility fractures. Springer, Cham, pp 241–256

English S, Coyle L, Bradley S, Wilton W, Cordner J, Dempster R et al (2021) Virtual fracture liaison clinics in the COVID era: an initiative to maintain fracture prevention services during the pandemic associated with positive patient experience. Osteoporos Int 32(6):1221–1226

van den Berg P, van Leerdam M, Schweitzer DH (2021) Covid-19 given opportunity to use ultrasound in the plaster room to continue secondary fracture prevention care: a retrospective Fracture Liaison Service study. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs 43:100899

Murray S, Langdahl B, Casado E, Brooks K, Libanati C, Di Lecce L et al (2022) Preparing the leaders of tomorrow: learnings from a 2-year community of practice in fragility fractures. J Eur CME 11(1):2142405

Sujic R, Beaton DE, Bogoch ER, Ontario Osteoporosis Strategy Fracture Clinic Screening Program Evaluation Team (2016) Patient acceptance of osteoporosis treatment: application of the stages of change model. Maturitas 88:70–75

Sargent GM, Forrest LE, Parker RM (2012) Nurse delivered lifestyle interventions in primary health care to treat chronic disease risk factors associated with obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev 13(12):1148–1171

Vallis M (2015) Are behavioural interventions doomed to fail? Challenges to self-management support in chronic diseases. Can J Diabetes 39(4):330–334

Tsamlag L, Wang H, Shen Q, Shi Y, Zhang S, Chang R et al (2020) Applying the information-motivation-behavioral model to explore the influencing factors of self-management behavior among osteoporosis patients. BMC Public Health 20(1):198

Akesson K, Marsh D, Mitchell PJ, McLellan AR, Stenmark J, Pierroz DD et al (2013) Capture the fracture: a best practice framework and global campaign to break the fragility fracture cycle. Osteoporos Int 24(8):2135–2152

Javaid MK, Sami A, Lems W, Mitchell P, Thomas T, Singer A et al (2020) A patient-level key performance indicator set to measure the effectiveness of fracture liaison services and guide quality improvement: a position paper of the IOF Capture the Fracture Working Group, National Osteoporosis Foundation and Fragility Fracture Network. Osteoporos Int 1:1193

Fragility Fracture Network (2020) FFN clinical toolkit. Fragility Fracture Network, Zurich

Fragility Fracture Network (2020) Fragility fracture network policy toolkit. Fragility Fracture Network, Zurich

Osuna PM, Ruppe MD, Tabatabai LS (2017) Fracture Liaison Services: multidisciplinary approaches to secondary fracture prevention. Endocr Pract 23(2):199–206

Hansen CA, Abrahamsen B, Konradsen H, Pedersen BD (2017) Women’s lived experiences of learning to live with osteoporosis: a longitudinal qualitative study. BMC Womens Health 17(1):17

MAPI Research Institute (2008) Patient-reported outcomes and quality of life instruments database (PROQOLID), Lyon, France 2008. https://www.qolid.org/

Duprez V, Vandepoel I, Lemaire V, Wuyts D, Van Hecke A (2022) A training intervention to enhance self-management support competencies among nurses: a non-randomized trial with mixed-methods evaluation. Nurse Educ Pract 65:103491

Barley E, Lawson V (2016) Using health psychology to help patients: theories of behaviour change. Br J Nurs 25(16):924–927

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Speerin, R., Marques, A., van Oostwaard, M. (2024). Secondary Fracture Prevention. In: Hertz, K., Santy-Tomlinson, J. (eds) Fragility Fracture and Orthogeriatric Nursing . Perspectives in Nursing Management and Care for Older Adults. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33484-9_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-33484-9_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-33483-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-33484-9

eBook Packages: MedicineMedicine (R0)