Abstract

There has recently been a surge in public social spending in emerging market economies (EMEs). We hypothesize that social unrest is a key “political” factor that drives this expansion, translating “structural” pressures into social expenditures. We test this hypothesis on a panel dataset of 48 countries between the years 1989 and 2015. Our results indicate that social unrest has a strong positive effect on social expenditure. We also find that when general strikes precede World Bank social policy recommendations, there is a positive interaction between strikes and the World Bank. We take these findings to indicate that social policies are adopted and extended by policymakers, at least partially, as a benevolent strategy to contain social unrest. Finally, the results suggest that international institutions, such as the World Bank, do not solely consider the well-being of people as an end in of itself, but also as a means of promoting political stability.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There has been an aggregate increase in social protection expenditures over the past several decades in most of the Global South and North, despite the expectations of the welfare state retrenchment literature (Korpi and Palme 2003; Scruggs and Allan 2008). Most countries in the Global South, especially the so-called emerging market economies, have opted for creating or expanding innovative welfare programs (i.e. conditional cash transfers, free health care for the poor, food aid and public works programs), while old age pension expenditures, care services and social assistance programs continue to expand in the Global North. When explaining welfare state expansion, most contemporary studies tend to emphasize structural factors, such as aging, previous development strategies, political institutions and the rise of the services sector (Haggard and Kaufman 2008; Pierson 2001; Rudra 2002). Without denying the importance of structuralist explanations, we contend that the contemporary literature has largely under-examined how social expenditures are influenced by the political concerns of national and supranational institutions, such as the containment of social unrest. There are a few previous works that tackle similar inquiries; however, they test the opposite direction of the relationship we are interested in: the effect that welfare has on contentious politics (see i.e. Burgoon 2006; Dunning 2008; Pierson 2001; Taydas and Peksen 2012; Weiss 2005). In this chapter, we set out to make a contribution by testing the extent to which social unrest affects public social expenditures.

There are reasons to believe that international financial institutions (IFIs), such as the World Bank, may be playing a mediating role in the relationship between contentious politics and social spending. The World Bank claims that many new social policies (such as social pensions and conditional cash transfers) in borrowing countries are a result of technocratic (read: non-political) imposition (Brooks 2004; Radin 2008). Yet, van Gils and Yörük (2017) show that political objectives have played a critical role in the content of World Bank recommendations, including the prevention and containment of social unrest. In that sense, they show that World Bank social policy recommendations are not solely based on technocratic concerns over poverty alleviation and development but are fueled by the Bank’s own political concerns about political stability. Thus, these observations have led us to question whether the social policy recommendations of IFIs, such as the World Bank, are mostly targeted at countries experiencing greater amounts of social unrest. Moreover, we are curious as to whether the World Bank’s recommendations are taken into consideration more seriously by borrowing countries if they are challenged by social unrest.

We, therefore, hypothesize that social unrest is a key factor which translates structural effects into actual welfare policies, as part of a benevolent government strategy to contain further unrest. Furthermore, we suspect that this process is facilitated by the intervention of IFIs. The results of our statistical analysis, on a sample of 48 countries from the Global North and South for the years between 1989 and 2015, indicate that social expenditures are, to a significant degree, positively related to social unrest, thus providing evidence of the social containment hypothesis. The results for our second hypothesis are less clear, as there is no evidence of a direct effect of the World Bank on social spending. However, in several models we find that the effect of certain types of social unrest (i.e. general strikes) is significant if interacted with World Bank social policy recommendations (WBSPRs). Thus, there is some evidence of a relationship between World Bank social policy interventions and government decisions to increase social spending as a reaction to social unrest. Taken together, we interpret these results as a sign that social unrest plays a role in how policymakers translate structural forces into actual social policies, as well as providing some insights into the conditions in which policymakers choose to diffuse social policy recommendations from IFIs, such as the World Bank.

Explaining Welfare State Development

The explanations for modern welfare state development since the nineteenth century can be classified into two main clusters: structural and political explanations. For the mid-twentieth century development of welfare in the West, structuralist theories suggest that the welfare state expanded as a “natural” response to industrialization and urbanization (a.k.a logic of industrialism thesis) (Cowgill 1974; Form 1979; Goldthorpe et al. 1969; Pampel and Weiss 1983) or to resolve the crisis of under-consumption following the Keynesian logic (Garraty 1978; Janowitz 1977; O’Connor 1973; Offe 1984). Scholars oriented toward political explanations have argued that demographic and economic exigencies do not automatically lead to changes in welfare policies. Rather, socio-structural factors are translated into social policies through political conflict and struggles. These scholars considered the mid-twentieth-century welfare expansion as part of a strategy to contain political disorder and mobilize popular support (Dawson and Robinson 1963; Jennings 1979; Olson 1982). For instance, in-depth investigations of the urban riots in the United States during the 1960s provide evidence of the state using welfare programs for controlling, containing and potentially repressing insurgent populations (Gurr 1980; Isaac and Kelly 1981; Offe 1982; Piven and Cloward 1971).

Unlike the previous literature, that delicately fused structural and political perspectives, dominant arguments concerning the contemporary developments of the welfare state have largely focused on how national governments take a number of structural factors into account when formulating social policies, such as globalization, rising poverty, unemployment, deindustrialization, aging and the rise of the services sector (Cerutti et al. 2014; Fernández and Jaime-Castillo 2012; Gough et al. 2004; Hemerijck 2012; Iversen 2001). This structuralist focus has not only characterized the studies on the original Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, but also greatly influenced the scope of questions asked in research on the Global South. For instance, research on the welfare-globalization nexus has often painted a gloomy picture, suggesting that a “race to the bottom” is taking placeFootnote 1 (Avelino et al. 2005; Kaufman and Segura-Ubiergo 2001; Rudra 2002; Wibbels 2006), the logic being that developing countries lack the domestic mediating factors of globalization found in the original OECD countries (for instance strong democratic institutions) (Haggard and Kaufman 2008; Rudra 2008). The overall evidence has largely contradicted the claims of a “race to the welfare bottom” in the Global South, such as an overall increase in public spending and the proliferation of new social welfare programs (Hulme et al. 2012). Thus, we argue that the globalization-welfare nexus literature provides a good example of the need to take into consideration factors which mediate structural effects into actual social policies, such as political effects and their interaction with international/external actors.

With regard to the influence of external actors, a number of studies have begun to place greater emphasis on the political concerns of supranational organizations, such as the World Bank, when explaining the formulation of social policies in the Global South (Brooks 2015; Simpson 2018). The official discourse of the World Bank is that its objectives are not political, but that it seeks to solve social ills, such as the alleviation of poverty (Litvack 2011; World Bank 2015). However, previous research has demonstrated that these claims do not match up to reality (van Gils and Yörük 2017). A number of studies have found clear references to political concerns in the World Bank’s policies (Barnett and Finnemore 2004; Benjamin n.d.; Goldman n.d.; Van de Laar 1976). For instance, van Gils and Yörük (2017) provide systematic evidence of the World Bank making politically motivated social policy recommendations, such as the prevention and containment of social unrest. While it is not surprising to see political rhetoric in the World Bank’s policy recommendations, these recommendations are subsumed under the Word Bank’s global “equitable growth” strategy. Thus, it appears that the World Bank does not see poverty alleviation as an end in and of itself, but rather as a means to reduce social unrest which could adversely affect the interests of donor governments (see Dodlova, Chap. 8, this volume).

This conclusion fits to the fact that the World Bank is a rationally structured bureaucratic institution with well-defined interests and goals. Furthermore, the Bank has to negotiate with member organizations in order to achieve these goals and maximize bureaucratic interests. This dependency structurally leads the Bank toward a conservative direction and to policy recommendations that are often politically driven. Therefore, when member states have exigencies for the containment of domestic unrest, the Bank is driven to provide blueprints for this course of action. Also, recommending social assistance for political containment is appealing because customers, as political actors, tend to internalize World Bank policy suggestions that would work politically at home. Therefore, recommendations that are politically helpful may find clients easier (Toye 2009).

The World Bank’s donor states have a strong influence on the Bank’s policymaking (Weaver and Leiteritz 2005), with the US remaining the most influential state (Fleck and Kilby 2006; Morrison 2013). Hence, the Bank acts as an overseer of global political stability, primarily due to the support from donor governments who may have their long-term security interests defended when considering stabilization goals which should, in turn, lead to less migration or terrorism (Keukeleire and Raube 2013, see also Shriwise, Chap. 2, this volume). Donors impose their interests through (1) direct appointment of the leadership cadres of the Bank, (2) donating the majority of funds, and (3) the threat of denying Bank funds access to the national private capital markets in case the Bank declines donors’ interests (Weaver 2008).

In sum, we turn to the careful fusion of structural and political factors, common among mid-twentieth-century welfare scholars, to explain recent trends in global welfare provision. According to this literature, the containment of social unrest is a political factor which translates the structural pressures for welfare expansion into actual increases in welfare spending. Furthermore, there are reasons to believe that IFIs, such as the World Bank, play a mediating role in the relationship between contentious politics and social spending by facilitating the containment of social unrest.

Data and Methods

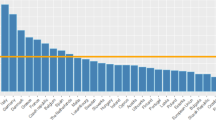

To answer our research questions, we conduct a panel data analysis on a sample of 48 countries from the Global North and South, across multiple world regions, for the years between 1989 and 2015.Footnote 2 Our sample does not include low-income/poor countries which run the risk of introducing a type 2 error to our analysis; as least developed countries have less capacity and resources to increase social protection spending even if policymakers prefer to address unrest through benevolent means. When referring to emerging market economies, we generally refer to countries which show many features of advanced industrialized economies (i.e. high levels of economic growth, open markets, etc.) but at the same time lack many of the common features of these countries (i.e. high GDP per capita, low unemployment and consistent socio-political stability). Although seeking to only include countries which match these characteristics approximates what we are referring to as an emerging market economy, we are nonetheless forced to deal with the difficulty that a commonly accepted definition which would delineate emerging market economies (EMEs) from least developed economies does not yet exist. Thus, to better identify a sample of cases, we include countries as EMEs if they are listed on any one of three popularly applied lists: International Monetary Fund (IMF), Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA) and the Emerging Market Bond Index Global (EMBI Global) by J.P. Morgan.

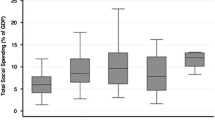

Table 9.1 provides summary statistics of our data. Our dependent variable is social protection spending, measured as a percentage of GDP.Footnote 3 Most data for the dependent variable come from the OECD social expenditure database (SOCX). The OECD data are complemented with our own calculations based on national government records and surveys, applying the OECD methodology. We are mainly concerned with the effect of two key independent variables, as well as with their interaction. First, we create an index variable for social unrestFootnote 4 composed of the total number of events per year for three major sources of social unrest: general strikes, riots and anti-government demonstrations. All three of these measures come from the cross-national time series (CNTS) domestic conflict event data.Footnote 5 The CNTS data currently offers the most reliable cross-national measures for the entire period of interest.

The second independent variable of interest is IFI influence. As an indicator of donor diffusion of policy ideas does not currently exist, we create a new measure based on the number of WBSPRs. This measure is based on a survey of a total of 447 World Bank social policy related documents and reports.Footnote 6 The core of the WBSPR measure counts the number of World Bank social policy recommendations given to a specific country in a given country-year.Footnote 7 This score is then added to the number of relevant regional reports. Finally, the World Bank occasionally publishes several highly influential policy documents which apply to every recipient country for the year in which the document was published. Thus, a single point is also added to every country-year in which an influential multi-country document is published. The equation to calculate the WBSPR variable is as follows:

The issue with measuring WBSPR as an interval variable is that it assumes that a one report increase leads to a single unit increase in the effect on social protection spending. As an extreme example, in the year 2013 we measure a total of 17 WBSPRs for China, up from 6 recommendations the previous year. Thus, as an interval variable, it is assumed that the World Bank impact is 11 times greater in 2013 than in 2012. However, it is unlikely that 17 reports have a much greater influence on social policy than 6 reports. Thus, for all our models we apply WBSPR as a simple dummy variable, (1) if there was a report in a given country-year and (0) if not.

As one of the few studies which cross-nationally analyzes the World Bank’s influence on social assistance, Brooks (2015) measures the World Bank leverage as the proportion of loans to country GDP. While this approach may yield general insights concerning the financial leverage of the Bank, financial flows are most likely one out of several mechanisms through which the World Bank exerts influence on policy choices. Other studies have laid the groundwork for cross-national statistical analysis by descriptively measuring the total number of World Bank social policy recommendations across all countries (van Gils and Yörük 2017). This approach moves beyond the World Bank’s financial leverage by measuring the diffusion of ideas and best practices. In this sense, measuring policy recommendations serves as a proxy for the extent to which the World Bank serves as a source of information, such as through specific policy reports identifying the changes the Bank would like to see implemented as well as technical support for their implementation. Thus, we use measures of both recommendations and financial flowsFootnote 8 to measure the influence of the World Bank, although most models apply WBSPR, as this more closely approximates what we are attempting to measure.

Several control variables are included to rule out alternative factors which might affect social protection spending. First, democracy is often hypothesized to be positively related to social protection and welfare measures (Rudra and Haggard 2005), although previous studies have also questioned this relationship (Dietrich and Bernhard 2016). Thus, in line with standard best practices, we include the Freedom House democracy scores as our measure of democracy. We also control for bureaucratic quality, which comes from the International Crisis Risk Group (ICRG), in order to gauge the degree to which a bureaucracy is professional, transparent and effective. The bureaucratic quality measure ranges from 0 to 4, from the lowest levels of bureaucratic quality to the highest. Including this measure is important, as it serves as our proxy of state capacity. States with higher capacity should find it less difficult to translate the preferences of policymakers into actual policies.

Along with political factors, we control for several macro-economic variables. As our measure of wealth, we include GDP per capita in constant 2010 dollarsFootnote 9 (Lequiller and Blades 2014). Including wealth in our model should be significantly related to social policy, all else being equal, as a greater share of resources can be allocated to social welfare programs. Additionally, we include GDP growth, thus controlling for the possibility that any variation in the dependent variable (which is measured as a percentage of GDP) is caused by differences in growth rates. For reasons discussed previously, we control for trade as a proxy for globalization, measured as exports plus imports as a percentage of GDP (IMF Statistics Department 2018). Lastly, we control for the old age composition of the population as a factor which should drive up the demand for greater social protection spending (population ages 65 or greater (% of total)) (United Nations 2018).

We use time-series generalized least squares (GLS) regression analysis to test the relationship between social protection spending, social unrest and WBSPR. To increase the robustness of our findings, we apply both random-effects and fixed-effects models. To control for potentially exogenous time trends, which could produce spurious relationships, we include a year-count variable (omitted from output tables). The equation for the model used in the analysis is as follows:

In the above equation, all independent variables are lagged by one year, since we expect their effect to take place after a short period, but not instantly. In alternate model specifications we also test the effects of social unrest using a two-year lag. Adding a two-year lag helps us to assess the interaction between WBSPR and social unrest, as we expect unrest to take place prior to the World Bank making a social policy recommendation. In other words, the logic goes as follows: at time A social unrest occurs → at time B the World Bank recommends increases in social policy → at time C countries react to the unrest and WBSPR by increasing social protection spending. The next section presents our findings.

Results

The results for our first four models can be found in Table 9.2. As can be seen in all the models, social unrest is positively related to social expenditures. While the effect of this variable is relatively small, this result is in line with our hypothesis that social containment plays a role in translating structural pressures into actual social policies. Models 2–4 include variables to measure the World Bank effect. In Models 2 and 3, the WBSPR variable is included to measure the diffusion of World Bank social policy ideas, whereas the total of multilateral loans is included in Model 4, as a measure of World Bank financial leverage. In all three models, the effect of international donors is insignificant. Thus, at first glance, it appears that the World Bank is not related to public social expenditures. All other signs of the coefficients in Table 9.2 point in the expected direction, except for bureaucratic quality. However, in alternative models, using World Bank Worldwide Governance Indicators (i.e. regulatory quality and government effectiveness) as the proxy of state capacity, the signs point in the expected positive direction. As these measures are strongly correlated with our measures of GDP and democracy, and thus potentially cause problems of multicollinearity, we keep bureaucratic quality as our main measure of state capacity, but with a skeptical eye toward how its inclusion affects our results.

Table 9.3 delves further into the interaction between social unrest and the World Bank. Throughout the models in Table 9.3, we include each component area of social unrest used to calculate the previous index variable and interact it with WBSPR. As can be seen in Model 5, including the different areas of social unrest without any interactions yields statistically significant results for general strikes and anti-government demonstrations. This supports the argument that governments tend to expand social policy as a strategy to contain different types of social unrest. Another key result of Model 6 is the positive significant relationship of the interaction between general strikes and WBSPRs. One way of interpreting this finding is that high levels of strike activity are related to the diffusion of World Bank social containment practices. While both general strikes and anti-government demonstrations are positive and significantly related to social spending, we do not observe a similar interaction effect between the WBSPR and anti-government demonstrations or riots. This might suggest that governments in this sample of countries implement World Bank practices only if there is a concrete material challenge emanating from the labor movement.

Given the weak significance of the interaction terms, this raises the possibility that the World Bank is not able to effectively transfer its social policy practices to states which would benefit most from the social containment strategy. This could explain the disconnect between a highly significant social unrest effect and the lack of a World Bank effect, despite the evidence that the Bank forwards a social containment strategy. Nevertheless, we remain optimistic that World Bank social policy interventions are related to government reactions to social unrest through welfare provision. We therefore turn to a marginal effects analysis in order to better understand how social expenditure changes at different levels of change in social unrest.

As can be seen in Figs. 9.1, 9.2, and 9.3, the results of the marginal effects analysis provide some support for the interaction results of general strikes and WBSPRs, highlighted in Model 6. According to the marginal effects analysis, there is a positive effect for WBSPRs in countries with more than five general strikes in a given country-year. A similarly positive trend can be seen in the interaction of anti-government demonstrations and WBSPRs, although this effect remains within the margin of error.

In sum, the results of the analysis indicate that public social spending and social unrest in general, and general strikes and anti-government demonstrations in particular, are significantly and positively related to each other. We also observe that in the case of general strikes this positive effect on social expenditures is heightened if interacted with WBSPRs. We interpret these findings to indicate that social protection spending is extended by policymakers by following the recommendations of the World Bank, as a securitization strategy to contain labor unrest. In general, we suggest that the securitization of social welfare policies depends on an understanding by policymakers that contentious groups may transform grievances into further political activism. Therefore, alleviating these grievances through social spending is seen as an “instrument” rather than an end in itself, to undermine the conditions of this radicalization. Finally, we take these findings to suggest that, at least in the case of general strikes, the World Bank does not solely consider the well-being of people when making social policy recommendations but also as a means of achieving similar political objectives.

Conclusions

There has recently been a global surge in public social spending. In this chapter we argue that social unrest is a key “political” factor that drives this expansion, translating “structural” pressures into social expenditures. We analyzed a cross-national panel dataset of 48 advanced and developing countries between the years 1989 and 2015. Our results indicate that social unrest, in general, and general strikes and anti-government demonstrations, in particular, have a positive relationship with social expenditures. We also find that when general strikes are interacted with WBSPRs, there is a positive interaction effect. This suggests that governments are more likely to translate WBSPRs into an expansion of social expenditure in countries with a higher number of general strikes. We take these findings to indicate that social policies are adopted and extended by policymakers, at least partially, as a benevolent strategy to contain social unrest. Finally, the results provide some support for the argument that international institutions, such as the World Bank, do not solely consider the well-being of people as an end in itself but also as a means of promoting political stability.

Although we remain optimistic about the World Bank’s role in the process outlined above, we are forced to deal with the fact that our results generally indicate a weak or insignificant relationship between WBSPR and social protection spending. As donors such as the World Bank are mainly interested in promoting social policy changes in certain programs, such as poverty relief, it is possible that these ideas are being diffused to policymakers without making a statistically significant short-term impact on overall social spending. Recent regional studies have begun to investigate this and have indeed found a significant relationship between the World Bank’s influence and the adoption of specific social welfare programs, such as conditional cash transfers (Simpson 2018). We therefore encourage future works to further investigate the mechanisms underlying the relationship between social spending and the World Bank’s influence through more regional and in-depth case study analyses.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

For a full list of countries, see Appendix.

- 3.

Social protection expenditure comprises public cash benefits, direct in-kind provision of goods and services and tax breaks for social purposes. Benefits may be targeted at low-income households, the elderly, disabled, sick, unemployed or young persons. To be considered “social”, programs must involve either the redistribution of resources across households or compulsory participation.

- 4.

The specific weights for the social unrest index are roughly in line with how CNTS scores their own weighted conflict index. The values entered are general strikes (20), riots (35) and anti-government demonstrations (10). We then multiplied the value for each variable by the specific weights; multiplied that sum of products by 100 and divided the result by 3.

- 5.

Events for these data are recorded through a comprehensive coding of newspaper articles. With regard to sources, the CNTS user’s manual notes that “while no bibliographic references are utilized in connection with these data, most are derived from The New York Times” (12).

- 6.

These include Country Focus reports, Economic and Sector work reports, Project Documents and documents from the Publications and Research department, including working papers. These are thus analytical as well as operational reports.

- 7.

To create this measure, we build on a previous dataset which followed a two-stage keyword search method (van Gils and Yörük 2017). In the first stage, documents on social policies are identified from the World Bank’s online archive. In the second stage, these documents are searched for twenty-four specific keywords that are likely to indicate the World Bank’s interest in political objectives. NVivo 10 is used to code all relevant documents.

- 8.

The measure of financial flows measures the amount of public and publicly guaranteed multilateral loans (World Bank International Debt Statistics). This measure includes loans and credits from the World Bank, regional development banks and other multilateral and intergovernmental agencies. However, as can be seen in Table 9.1, there is a significant amount of missing values for this data.

- 9.

World Bank national accounts data, and OECD National Accounts data files.

References

Avelino, George, David S. Brown, and Wendy Hunter. 2005. The Effects of Capital Mobility, Trade Openness, and Democracy on Social Spending in Latin America, 1980–1999. American Journal of Political Science 49 (3): 625–641.

Barnett, Michael N., and Martha Finnemore. 2004. Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Benjamin, Bret. n.d. Invested Interests: Invested Interests: Capital, Culture, and the World Bank. Accessed 25 July 2019. https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/invested-interests.

Brooks, Sarah M. 2004. What Was the Role of International Financial Institutions in the Diffusion of Social Security Reform in Latin America? In Learning from Foreign Models in Latin American Policy Reform, ed. Kurt Weyland. Washington, DC; Baltimore: Woodrow Wilson Center Press.

———. 2015. Social Protection for the Poorest: The Adoption of Antipoverty Cash Transfer Programs in the Global South. Politics and Society 43 (4): 551–582.

Burgoon, Brian. 2006. On Welfare and Terror Social Welfare Policies and Political-Economic Roots of Terrorism. Journal of Conflict Resolution 50 (2): 176–203.

Cerutti, Paula, Anna Fruttero, Margaret Grosh, Silvana Kostenbaum, Maria Laura Oliveri, Claudia Rodriguez-Alas, and Victoria Strokova. 2014. Social Assistance and Labor Market Programs in Latin America: Methodology and Key Findings from the Social Protection Database. Social Protection & Labor Discussion Papers No. 1401. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Accessed 7 November 2015. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2014/06/19737118/social-assistance-labor-market-programs-latin-america-methodology-key-findings-social-protection-database.

Cowgill, Donald O. 1974. The Aging of Populations and Societies. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 415 (1): 1–18.

Dawson, Richard E., and James A. Robinson. 1963. Inter-Party Competition, Economic Variables, and Welfare Policies in the American States. The Journal of Politics 25 (2): 265–289.

Dietrich, Simone, and Michael Bernhard. 2016. State or Regime? The Impact of Institutions on Welfare Outcomes. The European Journal of Development Research 28 (2): 252–269.

Dunning, Thad. 2008. Crude Democracy: Natural Resource Wealth and Political Regimes. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fernández, Juan J., and Antonio M. Jaime-Castillo. 2012. Positive or Negative Policy Feedbacks? Explaining Popular Attitudes Towards Pragmatic Pension Policy Reforms. European Sociological Review 29 (4): 803–815.

Fleck, Robert K., and Christopher Kilby. 2006. World Bank Independence: A Model and Statistical Analysis of US Influence. Review of Development Economics 10 (2): 224–240.

Form, William. 1979. Comparative Industrial Sociology and the Convergence Hypothesis. Annual Review of Sociology 5: 1–25.

Garraty, John A. 1978. Unemployment in History, Economic Thought and Public Policy. 1st ed. New York: Joanna Cotler Books.

van Gils, Eske, and Erdem Yörük. 2017. The World Bank’s Social Assistance Recommendations for Developing and Transition Countries: Containment of Political Unrest and Mobilization of Political Support. Current Sociology 65 (1): 113–132.

Goldman, Michael. n.d. Imperial Nature: The World Bank and the Struggles for Social Justice in the Age of Globalization. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Accessed 25 July 2019. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300104080/imperial-nature.

Goldthorpe, John H., David Lockwood, Frank Bechhofer, and Jennifer Platt. 1969. The Affluent Worker in the Class Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gough, Ian, Geoffrey Wood, A. Barrientos, P. Bevan, P. Davis, and Graham Room. 2004. Insecurity and Welfare Regimes in Asia, Africa, and Latin America: Social Policy in Development Contexts. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gurr, Ted R. 1980. Handbook of Political Conflict: Theory and Research. New York: “The” Free Press.

Haggard, Stephan, and Robert R. Kaufman. 2008. Development, Democracy, and Welfare States: Latin America, East Asia, and Eastern Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hemerijck, Anton. 2012. Changing Welfare States. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hulme, David, Joseph Hanlon, and Armando Barrientos. 2012. Just Give Money to the Poor: The Development Revolution from the Global South. Kumarian Press.

IMF Statistics Department. 2018. Direction of Trade Statistics Yearbook. http://data.imf.org/?sk=9D6028D4-F14A-464C-A2F2-59B2CD424B85&sId=1488236767350.

Isaac, Larry, and William R. Kelly. 1981. Racial Insurgency, the State, and Welfare Expansion: Local and National Level Evidence from the Postwar United States. American Journal of Sociology 86 (6): 1348–1386.

Iversen, Torben. 2001. The Dynamics of Welfare State Expansion: Trade Openness, Deindustrialization and Partisan Politics. In The New Politics of the Welfare State, ed. Paul Pierson. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Janowitz, Morris. 1977. Social Control of the Welfare State. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Jennings, Edward T., Jr. 1979. Competition, Constituencies, and Welfare Policies in American States. The American Political Science Review 73 (2): 414–429.

Kaufman, Robert R., and Alex Segura-Ubiergo. 2001. Globalization, Domestic Politics, and Social Spending in Latin America: A Time-Series Cross-Section Analysis, 1973–1997. World Politics 53 (4): 553–587.

Keukeleire, Stephan, and Kolja Raube. 2013. The Security–Development Nexus and Securitization in the EU’s Policies towards Developing Countries. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 26 (3): 556–572. Accessed 25 July 2019. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09557571.2013.822851.

Korpi, Walter, and Joakim Palme. 2003. New Politics and Class Politics in the Context of Austerity and Globalization: Welfare State Regress in 18 Countries, 1975–95. The American Political Science Review 97 (3): 425–446.

Lequiller, François, and Derek Blades. 2014. Understanding National Accounts. OECD.

Litvack, Jennie I. 2011. Social Safety Nets: An Evaluation of World Bank Support, 2000–2010. The World Bank. Accessed 24 July 2019. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/454481468165258565/Social-safety-nets-an-evaluation-of-World-Bank-support-2000-2010.

Mishra, Ramesh. 1996. The Welfare of Nations. In States Against Markets: The Limits of Globalization, ed. Robert Boyer and Daniel Drache, 238–251. London, New York: Routledge.

Morrison, Kevin. 2013. Membership No Longer Has Its Privileges: The Declining Informal Influence of Board Members on IDA Lending. The Review of International Organizations 8 (2): 291–312.

O’Connor, James. 1973. The Fiscal Crisis of the State. New Brunswick, NJ: St. Martin’s.

Offe, Claus. 1982. Some Contradictions of the Modern Welfare State. Critical Social Policy 2 (5): 7–16.

———. 1984. Contradictions of the Welfare State. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Olson, L. 1982. The Political Economy of the Welfare State. New York: Columbia University Press.

Pampel, Fred C., and Jane A. Weiss. 1983. Economic Development, Pension Policies, and the Labor Force Participation of Aged Males: A Cross-National, Longitudinal Approach. American Journal of Sociology 89 (2): 350–372.

Pierson, Paul. 2001. The New Politics of the Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Piven, Frances Fox, and Richard A. Cloward. 1971. Regulating the Poor: The Functions of Public Welfare. New York: Pantheon Books.

Radin, Dagmar. 2008. World Bank Funding and Health Care Sector Performance in Central and Eastern Europe. International Political Science Review 29 (3): 325–347.

Rudra, Nita. 2002. Globalization and the Decline of the Welfare State in Less-Developed Countries. International Organization 56 (2): 411–445.

———. 2008. Globalization and the Race to the Bottom in Developing Countries: Who Really Gets Hurt? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rudra, Nita, and Stephan Haggard. 2005. Globalization, Democracy, and Effective Welfare Spending in the Developing World. Comparative Political Studies 38 (9): 1015–1049.

Scruggs, Lyle A., and James P. Allan. 2008. Social Stratification and Welfare Regimes for the Twenty-First Century: Revisiting the Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. World Politics 60 (4): 642–664.

Simpson, Joshua. 2018. Do Donors Matter Most? An Analysis of Conditional Cash Transfer Adoption in Sub-Saharan Africa. Global Social Policy 18 (2): 143–168.

Taydas, Zeynep, and Dursun Peksen. 2012. Can States Buy Peace? Social Welfare Spending and Civil Conflicts. Journal of Peace Research 49 (2): 273–287.

Toye, John. 2009. Social Knowledge and International Policymaking at the World Bank. Progress in Development Studies 9 (4): 297–310.

United Nations. 2018. United Nations World Population Prospects.

Van de Laar, Aart J.M. 1976. The World Bank and the World’s Poor. World Development 4 (10): 837–851.

Weaver, Catherine. 2008. Hypocrisy Trap: The World Bank and the Poverty of Reform. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Accessed 25 July 2019. https://press.princeton.edu/titles/8779.html.

Weaver, Catherine, and Ralf J. Leiteritz. 2005. Our Poverty Is a World Full of Dreams: Reforming the World Bank. Global Governance 11 (3): 369–388. Accessed 25 July 2019. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/261776065_Our_Poverty_Is_a_World_Full_of_Dreams_Reforming_the_World_Bank.

Weiss, Linda. 2005. The State-Augmenting Effects of Globalisation. New Political Economy 10 (3): 345–353.

Wibbels, Erik. 2006. Dependency Revisited: International Markets, Business Cycles, and Social Spending in the Developing World. International Organization 60 (2): 433–468.

World Bank. 2015. The State of Social Safety Nets 2015. Washington, DC: World Bank. Accessed 7 November 2015. http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/978-1-4648-0543-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendix: Country List

Appendix: Country List

Argentina | Japan |

Australia | Latvia |

Austria | Malaysia |

Bangladesh | Mexico |

Belgium | Netherlands |

Brazil | New Zealand |

Bulgaria | Norway |

Canada | Oman |

Chile | Pakistan |

China | Peru |

Colombia | Philippines |

Czech Republic | Poland |

Denmark | Portugal |

Estonia | Russia |

Finland | Slovak Republic |

France | Slovenia |

Germany | South Africa |

Greece | South Korea |

Hungary | Spain |

India | Sweden |

Indonesia | Switzerland |

Ireland | Turkey |

Israel | United Kingdom |

Italy | United States |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Çemen, R., Yörük, E. (2020). The World Bank and the Contentious Politics of Global Social Spending. In: Schmitt, C. (eds) From Colonialism to International Aid. Global Dynamics of Social Policy . Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38200-1_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-38200-1_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-38199-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-38200-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)