Abstract

Increased level of flexibility is essential in power systems with high penetration of renewable energy sources in order to maintain the balance between the demand and generation. Actually, the flexibility provided by energy storage systems and flexible conventional resources (i.e., generating units) can play a vital role in the compensation of the renewable energy sources variability. In this paper, the flexibility of the conventional generating units is quantified and incorporated in a unit commitment model in order to evaluate the impact of different system flexibility levels on the optimal generation dispatch and on the operational cost of the power system. An emerging flexible option such as the battery storage is included in the unit commitment formulation, evaluating the flexibility contribution of the storage and its effect on the system operational cost. In this paper, the flexibility of a real power system is assessed while the unit commitment problem is formulated as a mixed-integer linear program. The results show that the integration of a storage unit in the power generation portfolio provides a significant amount of flexibility and reduces the system operational cost due to the peak shaving and valley filling.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The increasing integration of the renewable energy sources (RES) into the power system causes several operating and security problems due to the inherent stochastic nature of RES. A problem that might arise due to the stochasticity of the power generation from RES is the maintenance of the power balance in case that the share of renewables in the generation mix is very large. This means that sufficient resources must be scheduled by system operators in order to maintain the load-generation balance at all instances. In other words, the operators should have the flexibility to response in any abrupt changes of the power generation from RES [1, 2]. Flexibility can improve the efficient power system operation, and as a result to reduce the operating cost, consumer prices and the operational risk. The flexibility can be provided by flexible resources such as generating units, energy storage systems (ESSs), interconnections with neighboring systems, demand response schemes, grid strength and forecasting accuracy [3, 4].

The flexibility provided by conventional generating units is very important since these units are the main resource for satisfying the net load. The flexibility potential of the generating units depends by their present operational state and their technical characteristics such as operational range, ramping rates, start-up time, shut-down time, and the minimum up and down times. There are several indices in the literature to assess the flexibility of the system. In [5,6,7], a flexibility index is defined in order to quantify the flexibility of each type of generating unit. This index is mainly based on the technical characteristics of each unit. Also, the calculated flexibility index in [6] is incorporated in a unit commitment (UC) model to investigate the impact of generators flexibility in the day-ahead operational decisions. In [7], the flexibility indices of the generators are integrated in a dedicated unit construction and commitment (UCC) algorithm in order to determine the optimal investments in flexible generating units. Results show that the increase of the system flexibility can handle more uncertainties in load and generation. At the same time though the greater flexibility provided by conventional generating units results in an additional operating cost.

ESSs are an emerging technology that can reduce the operational cost of the system in valley filling and peak shaving applications, due to their ability to absorb power during low-cost hours and to inject power during high-cost hours [8, 9]. Also, ESSs are very flexible resources that can be used in compensating the intermittent and uncontrollable character of RES. In [10], an ESS is incorporated in a UC model in order to evaluate the storage profits under a high penetration of RES. Similarly, in [11], the integration of ESSs in a stochastic UC model reduces the wind power curtailment and the system operation cost under a high penetration of wind power.

This paper evaluates the operational flexibility provided by conventional generating units in a real isolated power system. The flexibility of the system is quantified according to [5], and the resulting flexibility indices are incorporated in a UC model as a constraint, in order to assess the impact of different system flexibility levels on the optimal generation dispatch and on the operational cost of the system. Further, the flexibility contribution of a possible integration of a battery storage in the system, and its effect on the system operational cost is investigated. The UC problem of the system with the integration of the battery storage and the consideration of the flexibility index is formulated as a mixed-integer linear program which is solved by a commercial solver. Finally, the total upward and downward flexibility of the system is calculated through the generation dispatch and the storage operation of the UC solution for different levels of system flexibility provided by the conventional units. The main contributions of this work are the following:

-

(a)

The proposed formulation for the flexibility assessment is applied to a real power system in which the impact of the integration of a battery storage on the flexibility and the operating cost of the system are examined.

-

(b)

In [12], the total upward and downward flexibility provided by the conventional units and the battery storage is determined without the incorporation of the units’ flexibility indices into the UC. In this work, the units’ flexibility indices are incorporated in the UC, and the total upward and downward flexibility is calculated for different minimum levels of system flexibility provided by the conventional units.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, the flexibility indices of the generating units are calculated. Also, in Sect. 3, the UC formulation is presented, while the calculation of the upward and downward flexibility is following in Sect. 4. Simulation results are presented in Sect. 5 and the paper concludes in Sect. 6.

2 Flexibility Index Calculation

The flexibility index of each generating unit is determined by constructing the composite flexibility metric (CFM) proposed in [5]. The flexibility index is calculated based on seven technical characteristics of the generating units namely, the minimum stable generation level, operating range, ramp up/down capabilities, start-up time, and minimum up and down time. Since the technical characteristics are expressed in different units of measurements and in disproportionate scales a normalization is required. The normalization procedure ensures that an increase in the value of a technical characteristic increases also the flexibility index. Moreover, the normalized characteristics can be compared and aggregated. The min-max normalization technique is used to convert all the technical characteristics to a similar range between 0 and 1 as shown in (1).

where \( x_{ji} \) is the value of technical characteristic \( j \) of unit \( i \), \( I_{ji} \) is the normalized value of \( x_{ji} \), while \( min_{i} \left( {x_{ji} } \right) \) and \( max_{i} \left( {x_{ji} } \right) \) are associated with the minimum and maximum values respectively of the technical characteristic \( j \) across all the units.

The next step for the construction of the flexibility index is the weighting. The weighting model of [5] is used for assigning weight to each technical characteristic, which reflect the importance of each characteristic in the provision of flexibility. According to the weighting model, the most important characteristics of the units in the provision of flexibility are the minimum stable generation level, the operating range, and the start-up time. In the last step of the CFM calculation, the flexibility index (\( Flex_{i} \)) of each unit is calculated using (2), by calculating the summation of the normalized values of the technical characteristics (\( I_{ji} \)) multiplied by their associate weights (\( w_{j} \)).

where \( K \) and \( J \) are the technical characteristics which are positively and negatively correlated with the supply of flexibility respectively. It must be noted that the value of the flexibility index of each generating unit (\( Flex_{i} \)) is between 0 and 1, and the highest value determine the most flexible unit.

3 Unit Commitment Formulation

In this section, a UC formulation is proposed which incorporates the calculated flexibility indices, in order to investigate the impact of different flexibility levels on the optimal generation dispatch and on the operational cost of the system. Also, a battery storage is included in the unit commitment formulation, in order to evaluate the flexibility contribution of the storage and its effect on the system operational cost. The unit commitment problem is formulated as a mixed-integer linear program (MILP) along an arbitrary time horizon \( T \) with one hour time intervals. The quadratic cost function of the generating units is approximated by a piece-wise linear function in order to use the MILP technique to solve the problem. Note that the accuracy of this approximation can be controlled by the number of the linear segments considered.

3.1 Objective Function

The objective function of this optimization problem is presented in (3) and targets to minimize the total operational cost of the system. More specifically, the generation and the commitment cost of the generating units is minimized for the whole period of study. In this work, zero marginal cost is assumed for RES power penetration and a strictly priority dispatch is maintained. Also, it is assumed that no RES generation curtailments as well as no load shedding is performed.

where \( T \) and \( U \) are the time periods (hours) and the number of generating units; variables \( p_{i}^{t} \), \( b_{i}^{t} \) and \( z_{i}^{t} \) are the generation (continues), on/off states (binary) and the start-up state (binary) of unit \( i \) at time \( t \); \( F_{i} \left( {p_{i}^{t} } \right) \) is the piece-wise linear cost function of the generation \( p_{i}^{t} \) for unit \( i \) at time \( t \); \( N_{i} \) and \( S_{i} \) are the no-load cost and the start-up cost of unit \( i \).

3.2 Constraints

The following equations presents all the constraints and conditions of the model:

-

1.

System Flexibility: The total system flexibility of the power system is calculated as the summation of the flexibility indices (\( Flex_{ i} \)) of the committed units for the whole simulation period and must be greater than the minimum total system flexibility (MTF). A larger value of MTF forces more flexible units to be committed in order to satisfy the system flexibility constraint which is shown in (4). Note that \( Flex_{ i} \) and MTF are expressed in per-unit (p.u).

$$ \mathop \sum \limits_{t = 1}^{T} \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^{U} Flex_{i} \times b_{i}^{t}\; \ge \; MTF $$(4) -

2.

Generation Limits & Units Start-up: The produced power from each committed unit must be within a range defined by their minimum \( (P_{i}^{min} ) \) and maximum \( (P_{i}^{max} ) \) operating limits. Also, the produced power from the decommitted units must be zero. As a result, \( p_{i}^{t} \) is a discontinued variable and this constraint is shown in (5). The constraint in (6) forces the start-up variables (\( z_{i}^{t} \)) to take the value 1 when the corresponding units were off at time \( t - 1 \) and switch on at time \( t \). Thus, the start-up cost of these units is added to the objective function. In every other case, these variables are set to zero.

$$ \begin{array}{*{20}l} {p_{i}^{t} \le P_{i}^{max} \times b_{i}^{t} , \quad \,\,\forall i, \forall t } \hfill \\ {p_{i}^{t} \; \ge \; P_{i}^{min} \times b_{i}^{t} , \quad \,\,\forall i, \forall t } \hfill \\ \end{array} $$(5)$$ - b_{i}^{t - 1}\; +\; b_{i}^{t}\; \le \; z_{i}^{t} , \quad \,\,\forall i, \forall t \in \left[ {2,T} \right] $$(6) -

3.

Power Balance: The produced power from the committed units plus the discharging power (\( p_{Dis}^{t} \)) of the battery must be equal to the net load (\( D^{t} \)) plus the charging power (\( p_{Ch}^{t} \)) of the battery for each time interval \( t \). \( D^{t} \) is defined as the load demand minus the RES power. \( s_{d} \) and \( s_{c} \) are the discharging and charging coefficients of the battery.

$$ \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^{U} p_{i}^{t} + s_{d} \times p_{Dis}^{t} = \frac{1}{{s_{c} }} \times p_{Ch}^{t} + D^{t} , \quad \,\,\,\,\forall t $$(7) -

4.

Spinning Reserve: The available power from the committed units must be greater than summation of \( D^{t} \) and the spinning reserve (\( R^{t} \)) excluding the discharging power of the battery. In this work, the battery storage does not contribute in the supply of reserve, however the discharging power of the battery is subtracted from the net load.

$$ \mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^{U} b_{i}^{t} \times P_{i}^{max}\; \ge \;D^{t} + R^{t} - s_{d} \times p_{Dis}^{t} , \quad \,\,\forall t $$(8) -

5.

Primary Reserve: The available primary reserve from the committed units must be equal or greater than the minimum primary reserve \( \left( {PR^{min,t} } \right) \) of the system for each time interval t (9). The available primary reserve (\( q_{i}^{t} \)) of each committed unit is defined as the difference between the maximum and the actual generation of the unit (10). Also, the available primary reserve of each committed unit must be less than its maximum (\( Q_{i}^{max} \)) bound (11).

$$ \mathop \sum \limits_{{\varvec{i = }{\mathbf{1}}}}^{\varvec{U}} \varvec{q}_{\varvec{i}}^{\varvec{t}}\; \ge\; \varvec{PR}^{{\varvec{min},\varvec{t}}} ,\,\,\forall \varvec{t} $$(9)$$ q_{i}^{t}\; \le\; P_{i}^{max} - p_{i}^{t} , \quad \,\,\forall i,\forall t $$(10)$$ q_{i}^{t}\; \le\; Q_{i}^{max} \times b_{i}^{t} , \quad \,\,\forall i,\forall t $$(11) -

6.

Minimum Up & Down times: There is a minimum time (\( Up_{i} \)) that units must remain online after their commitment (12). Also, there is a minimum time (\( Dp_{i} \)) that generating units must remain offline after their decommitment (13).

$$ \begin{array}{*{20}c} {b_{i}^{t} - b_{i}^{t - 1}\; \le \;b_{i}^{{T_{up} }} , } \\ { \forall i,T_{up} \in \left[ {t + 1,\hbox{min} \left\{ {t + Up_{i} - 1,T} \right\}} \right],} \\ {\forall t \in \left[ {2,T - 1} \right]} \\ \end{array} $$(12)$$ \begin{array}{*{20}c} {b_{i}^{t - 1} - b_{i}^{t} \le 1 - b_{i}^{{T_{down} }} , } \\ {\forall i,T_{down} \in \left[ {t + 1,{ \hbox{min} }\left\{ {t + Dp_{i} - 1,T} \right\}} \right],} \\ {\forall t \in \left[ {2,T - 1} \right]} \\ \end{array} $$(13) -

7.

State of Charge: The state of charge (\( SOC_{t} \)) of the battery storage in time \( t \) is measured in MWh and is expressed as the initial capacity (\( IC \)) of the storage minus the summation of the discharging power plus the summation of the charging power for all the past and the present time intervals. Also, \( SOC_{t} \) must be within the minimum (\( SOC_{min} \)) and maximum (\( SOC_{max} \)) state of charge of the battery storage in MWh. The state of charge constraint is presented in (14). Note that the energy of the battery (SOC) with the charging and discharging power of the battery are related since, in the simulations only one hour time intervals are considered.

$$ \begin{array}{*{20}l} {SOC_{t} = IC - \mathop \sum \limits_{\tau = 1}^{t} p_{Dis}^{\tau } + \mathop \sum \limits_{\tau = 1}^{t} p_{Ch}^{\tau } ,\quad \;\forall t} \hfill \\ {SOC_{t} \; \ge \; SOC_{min} ,\,\,\,SOC_{t} \; \le \; SOC_{max} ,\,\,\forall t} \hfill \\ \end{array} $$(14) -

8.

Battery Storage Restriction: The simultaneous charging and discharging of the battery storage at the same time interval is restricted through (15) and (16). Also, the charging and discharging power in MW must be less than the maximum charging (\( P_{Ch}^{max} \)) and discharging (\( P_{Dis}^{max} \)) power of the battery storage (15). Note that \( v_{t} \) and \( n_{t} \) are binary variables associated with the discharging and charging power respectively.

$$ \begin{array}{*{20}l} {0 \; \le \; p_{Dis}^{t} \; \le \; P_{Dis}^{max} \times v_{t} , \quad \;\forall t } \hfill \\ {0 \; \le \; p_{Ch}^{t} \; \le \; P_{Ch}^{max} \times n_{t} , \quad \;\forall t} \hfill \\ \end{array} $$(15)$$ v_{t} + n_{t} \; \le \; 1,\quad \forall t $$(16)

It should be noted that the ramp-up and ramp-down constraints of the generating units are ignored in this study, since the units can change their production from the minimum to the maximum and vice versa, in one-hour time interval (as considered in this study).

4 Upward and Downward Flexibility

The ability of the system to respond to abrupt power changes in a certain time period depends on the level of the flexibility that exist in the system. This capability of the system is defined as the upward and downward flexibility. In this section, the equations related to the total upward and downward flexibility provided by the generating units and the battery storage are shown. In this work, the calculation of the system upward and downward flexibility indicates the impact of the battery storage and the incorporated flexibility indices (to the unit commitment problem) on the ability of the system to respond to power changes.

The upward flexibility provided by the conventional generating units is presented in (17) and it is actually the extra power that can be produced by the committed units between the time intervals which are taken into account. In contrast, the downward flexibility (calculated as shown in (18)) is the total power that the committed units are able to reduce (based on the minimum stable operating level). In this work, based on the results of the UC the upward and downward flexibility of the system are calculated for the whole simulation period.

The provision of upward and downward flexibility from a battery storage depends on its current state of operation and is limited by its capacity and its current stored energy. For example, a battery storage is not able to provide upward flexibility if it is fully discharged and similarly, it cannot provide downward flexibility if it is fully charged. In (19) and (20) the upward and downward flexibility that can be provided by the battery in the time period \( T_{1} \) where the battery operates in discharging mode is presented. Similarly, the upward and downward flexibility provided by the battery for the time periods (\( T_{2} \,\& \, T_{3} \)) where the battery operates at the charging and the non-working mode respectively can be calculated through (21)–(24). It is assumed that the battery storage cannot change its operation mode in the same time interval (i.e. change from charging to discharging mode). In reality though, the battery can change its state of operation in the same time interval providing greater amount of flexibility. This will be a part of the future work.

In (19), the upward flexibility is defined as the minimum amount of energy between the stored energy (MWh), i.e. SOC and the power (MW) that the battery can provide (according to the maximum discharge of the battery). The flexibility in (20) and (21) can be provided by stopping the discharging or the charging of the battery, respectively. In (22), the downward flexibility is calculated as the minimum between the available extra charging power that the battery can absorb and its available capacity for storing energy. The upward flexibility of the non-working state (23) is defined as the minimum between the maximum discharging power and the state of charge of the battery, while in (24) the downward flexibility of this state is the minimum between the maximum charging power and the available energy that the battery can store.

5 Simulation Results

In this section the impact of the battery storage integration and the incorporation of the flexibility indices (in the unit commitment problem) on the system operating cost is investigated. The investigation is performed on the upward and downward flexibility of the isolated power system of Cyprus. The installed capacity of the conventional units of the power system of Cyprus is 1478 MW, while the installed capacity of wind and PV power is 157 MW and 125 MW respectively. The proposed MILP formulation is coded in Matlab and a commercial solver is used to solve the problem using real data of the power system of Cyprus. More specifically, this problem is solved for two consecutive summer days (48 h), using the load demand and the RES penetration of these days as input data. Those days, the maximum RES penetration reached 11.48% of the peak of the load. Note that a horizon of 24 h can also be applied in order to be associated with the day-ahead market, however a longer period of time is used in this work to examine the impact of the battery storage in a longer time period. Two batteries of 60 MWh and 120 MWh with maximum charging and discharging power of 60 MW and 120 MW are considered in the simulations [6]. It is assumed that the round trip efficiency of the batteries is 92%, and their aforementioned capacities are the usable capacities. Therefore, the nominal capacity of the batteries is greater.

The impact of the 120 MWh battery storage on the operation of the power system of Cyprus is presented in Fig. 1. More specifically, the generating power from the conventional units with and without the integration of the battery is illustrated in Fig. 1(a) for the 48 h horizon. Also, the state of charge of the battery is presented in Fig. 1(b). Initially, it is assumed that the battery is fully discharged. Note that the 120 MWh is the usable capacity of the battery, and we assume that there are no limitations about the minimum state of charge of the battery. The valley filling and peak shaving applications of the battery storage are obvious in Fig. 1(a). The integration of the battery storage manages to reduce the range between the maximum and the minimum produced power, with a great benefit on the operational cost of the system due to the fact that less generating units need to be committed and decommitted in order to satisfy the security and the technical constraints of the system.

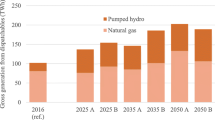

Figure 2 illustrates the rise of the system operational cost in respect with the increment of the system flexibility (MTF) for the cases with and without the battery storage integration. Note that the system flexibility constraint become binding for values greater than 310 (p.u) for the case of the battery integration, and for values greater than 320 (p.u) for the case of no battery integration. This means that for smaller values, the system flexibility constraint does not affect the optimal solution. As it can be seen in this figure, the system operational cost increases significantly with the increase of the MTF due to the fact that more flexible generating units as well as additional generating units are needed to be committed in order to satisfy the flexibility requirements. Also, the cost reductions due to the integration of the battery storage are presented in Table 1 as the system profits compared to the case without the battery storage integration. The profit with the battery integration is very high when the system flexibility constraint is non-binding and is reduced significantly when this constraint becomes binding. This is mainly because only the generating units are considered as flexible resources in the current UC formulation. It should be noted that the consideration of the battery as a flexible resource will be the subject of future work.

The total upward and downward flexibility provided by the generating units and the battery storage is calculated for several values of the minimum flexibility and are presented in Tables 2 and 3. It is clear that the total upward flexibility increases dramatically as the minimum flexibility value increases, and this is due to the commitoment of additional generating units and their dispatch at lower operating levels. In contrast, the total downward flexibility decreases because the committed generating units are dispatched at lower operating levels. However, as the results show, this reduction on the downward flexibility is not very significant. The integration of a battery storage has a significant effect on the provision of upward and downward flexibility. This is evident by the substantial increment of the upward and downward flexibility compared to the case without the battery storage. Note that the maintenance of high upward and downward operational flexibility is essential in order to compensate the variability of RES.

6 Conclusions

In this paper, a unit commitment formulation incorporating a battery storage and a constraint for the system flexibility is proposed. This proposed formulation was used for investigating the impact of different system flexibility levels and the battery storage integration on system flexibility and on the operational cost of a real power system. Results indicate that the provision of a high system flexibility from the conventional units is costly but provides significant amounts of upward flexibility in order to compensate the variability of RES. However, the integration of a battery storage manages to reduce the system operational cost and increase significantly the upward and downward flexibility of the system.

References

Wu, Y., Li, Y., Wu, Y.: Overview of power system flexibility in a high penetration of renewable energy system. In: IEEE International Conference on Applied System Invention (ICASI), Chiba, pp. 1137–1140 (2018)

Ma, J., Silva, V., Ochoa, L.F., Kirschen, D.S., Belhomme, R.: Evaluating the profitability of flexibility. In: IEEE PES General Meeting, San Diego, CA, pp. 1–8 (2012)

Kiviluoma, J., Rinne, E., Helistö, N.: Comparison of flexibility options to improve the value of variable power generation. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 37, 761–781 (2018)

Helistö, N., Kiviluoma, J., Holttinen, H.: Long-term impact of variable generation and demand side flexibility on thermal power generation. IET Renew. Power Gener. 12(6), 718–726 (2018)

Oree, V., Hassen, S.Z.: A composite metric for assessing flexibility available in conventional generators of power systems. Appl. Energy 177, 683–691 (2016)

Heydarian-Forushani, E., Golshan, M.E.H., Siano, P.: Evaluating the operational flexibility of generation mixture with an innovative techno-economic measure. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 33(2), 2205–2218 (2018)

Ma, J., Silva, V., Belhomme, R., Kirschen, D.S., Ochoa, L.F.: Evaluating and planning flexibility in sustainable power systems. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 4(1), 200–209 (2013)

Lobato, E., Sigrist, L., Rouco, L.: Use of energy storage systems for peak shaving in the Spanish Canary Islands.In: IEEE PES General Meeting, Vancouver, BC, pp. 1–5 (2013)

McPherson, M., Tahseen, S.: Deploying storage assets to facilitate variable renewable energy integration: the impacts of grid flexibility, renewable penetration, and market structure. Energy 145, 856–870 (2018)

O’Dwyer, C., Ryan, L., Flynn, D.: Efficient large-scale energy storage dispatch: challenges in future high renewable systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 32(5), 3439–3450 (2017)

Amoli, N.A., Sakis Meliopoulos, A.P.: Operational flexibility enhancement in power systems with high penetration of wind power using compressed air energy storage. In: Clemson University Power Systems Conference (PSC), Clemson, SC, pp. 1–8 (2015)

Yang, J., Zhang, L., Han, X., Wang, M.: Evaluation of operational flexibility for power system with energy storage. In: International Conference on Smart Grid and Clean Energy Technologies (ICSGCE), Chengdu, pp. 187–191 (2016)

Acknowledgments

This paper is part of the FLEXITRANSTORE project. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 774407.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this paper

Cite this paper

Tziovani, L. et al. (2020). Assessing the Operational Flexibility in Power Systems with Energy Storage Integration. In: Németh, B., Ekonomou, L. (eds) Flexitranstore . ISH 2019. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering, vol 610. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37818-9_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-37818-9_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-37817-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-37818-9

eBook Packages: EngineeringEngineering (R0)