Abstract

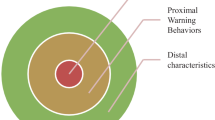

In this chapter, we presents the results from a multi-method study in the Netherlands into the role of socio-economic and psychological factors underlying terrorism involvement. Building on theories and findings of previous researchers in the field, we present a descriptive model of terrorism that categorizes distal and proximal ‘threat triggers’. In the quantitative part of the study, we analysed a combined data set on suspects of terrorist offenses, a control sample of the general population and a sample of general offenders. Terrorism suspects were more often lower educated, unemployed, and previously involved in crime compared to persons from the general population with the same gender and age. Relatively often, they had lost their job or became imprisoned for another crime a year before they were charged with a terrorist offense. In the qualitative part of the study, we conducted interviews with four detainees from terrorist units, eight detainees charged with traditional crimes (as reference group), and 18 professional informants that had personal experience with current and former detainees on terrorism and other offenses. The results of these interviews suggest that among terrorist offenders, early family experiences, attachment problems, and mental health issues increase feelings of perceived threat, which further justify violent narratives of belonging and significance.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

- 1.

Both quantitative and qualitative studies have been approved by the ethical board of the Faculty of Law from the VU university in Amsterdam.

- 2.

- 3.

In the aftermath of the Theo van Gogh murder, two prominent jihadi networks, known as the Hofstad group and the Context group, have been dismantled by the security services.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

- 7.

- 8.

See Van Ham et al. (2018), https://www.wodc.nl/binaries/2867_Summary_tcm28-323558.pdf

- 9.

- 10.

The database contains the personal data of people who (used to) live in Netherlands. Municipalities record the personal data of all residents in the BRP. For information, see: https://www.government.nl/topics/personal-data/personal-records-database-brp

- 11.

Research on Dutch jihadi networks demonstrates the involvement of vulnerable immigrants in the Netherlands (De Bie et al. 2014). For additional information on who is excluded from the BRP, see the CBS-website: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/achtergrond/2017/38/basisregistratie-personen (this information is only available in Dutch).

- 12.

For age, we made age categories and matched the age groups of the terrorism suspects with the control groups.

- 13.

For the dynamic variables of the control groups (which were based on 2016 information), we used data from the year 2015.

- 14.

As explained before, the education data was excluded from the logistic regression analyses due to the structural missings.

- 15.

For some terrorism suspects, we had missing data on a range of variables. Therefore, we excluded them from the analyses.

- 16.

Inclusion of the variable unemployment in Model I resulted in a significant Hosmer en Lemeshow test, which is an indication that the model is not a good fit. Therefore, we ran Model I without this variable.

References

Agnew, R. (2014). General strain theory. In G. Bruinsma & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice (pp. 1892–1900). New York: Springer.

Agnew, R. (2016). General strain theory and terrorism. In G. LaFree & J. D. Freilich (Eds.), The handbook of the criminology of terrorism (pp. 119–132). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Andersen, H., & Mayerl, J. (2018). Attitudes towards Muslims and fear of terrorism. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(15), 2634–2655.

Andriessen, I., Fernee, H., & Wittebrood, K. (2014). Ervaren discriminatie in Nederland. The Hague: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

Bakker, E., & de Bont, R. (2016). Belgian and Dutch jihadist foreign fighters (2012–2015): Characteristics, motivations, and roles in the War in Syria and Iraq. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 27(5), 837–857.

Balen, M., & van den Bos, K. (2017). Over waargenomen onrechtvaardigheid en radicalisering. Justitiële Verkenningen, 43(3), 31–44.

Basra, R., & Neumann, P. R. (2016). Criminal pasts, terrorist futures: European jihadists and the new crime-terror nexus. Perspectives on Terrorism, 10(6), 25–40.

Bergema, R., & van San, M. (2019). Waves of the black banner: An exploratory study on the Dutch jihadist foreign fighter contingent in Syria and Iraq. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 42(7), 636–661.

Borum, R. (2011). Radicalization into violent extremism I: A review of social science theories. Journal of Strategic Security, 4(4), 7–36.

Bowles, S. (2009). Did warfare among ancestral hunter-gatherers affect the evolution of human social behaviors? Science, 324(5932), 1293–1298.

Bracha, H. S. (2004). Freeze, flight, fight, fright, faint: Adaptationist perspectives on the acute stress response spectrum. CNS Spectrums, 9(9), 679–685.

Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55(3), 429–444.

Buss, D. (2015). Evolutionary psychology: The new science of the mind. New York: Psychology Press.

Brewer, M. B., & Campbell, D. T. (1976). Ethnocentrism and intergroup attitudes: East African evidence. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Choma, B. L., Charlesford, J. J., Dalling, L., & Smith, K. (2015). Effects of viewing 9/11 footage on distress and Islamophobia: A temporally expanded approach. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45(6), 345–354.

Cuddy, A. J., Glick, P., & Beninger, A. (2011). The dynamics of warmth and competence judgments, and their outcomes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 31, 73–98.

de Bie, J. L. (2016). How jihadist networks operate: a grounded understanding of changing organizational structures, activities, and involvement mechanisms of jihadist networks in the Netherlands. Leiden: Leiden University.

de Bie, J. L., de Poot, C. J., & van der Leun, J. P. (2014). Jihadi networks and the involvement of vulnerable immigrants: Reconsidering the ideological and pragmatic value. Global Crime, 15(3–4), 275–298.

de Bie, J. L., de Poot, C. J., & van der Leun, J. P. (2015). Shifting modus operandi of jihadist foreign fighters from the Netherlands between 2000 and 2013: A crime script analysis. Terrorism and Political Violence, 27(3), 416–440.

de Graaf, B. A. (2017). Terrorisme-en radicaliseringsstudies: Een explosief onderzoeksveld. Justitiele Verkenningen, 43(3), 8–30.

de Poot, C. J., Sonnenschein, A., Soudijn, M. R. J., Bijen, J. G., & Verkuylen, M. W. (2011). Jihadi terrorism in the Netherlands. The Hague: Boom Juridische Uitgevers.

Decker, S., & Pyrooz, D. (2011). Gangs, terrorism, and radicalization. Journal of Strategic Security, 4(4), 151–166.

Doosje, B., Loseman, A., & van den Bos, K. (2013). Determinants of radicalization of Islamic youth in the Netherlands: Personal uncertainty, perceived injustice, and perceived group threat. Journal of Social Issues, 69(3), 586–604.

Feddes, A. R., Mann, L., & Doosje, B. (2015). Increasing self-esteem and empathy to prevent violent radicalization: A longitudinal quantitative evaluation of a resilience training focused on adolescents with a dual identity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45(7), 400–411.

Feddes, A. R., Nickolson, L., & Doosje, B. (2015). Triggerfactoren in het radicaliseringsproces. Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam.

Feldman, S., & Stenner, K. (1997). Perceived threat and authoritarianism. Political Psychology, 18(4), 741–770.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 878–902.

Gallagher, M. J. (2014). Terrorism and organised crime: Co-operative endeavours in Scotland? Terrorism and Political Violence, 26(2), 320–336.

Glick, P. (2002). Sacrificial lambs dressed in wolves’ clothing. In L. S. Newman & R. Erber (Eds.), Understanding genocide:The social psychology of the Holocaust (pp. 113–142). London: Oxford University Press.

Huddy, L., Feldman, S., & Weber, C. (2007). The political consequences of perceived threat and felt insecurity. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 614(1), 131–153.

Hutchinson, S., & O’Malley, P. (2007). A crime–terror nexus? Thinking on some of the links between terrorism and criminality. Studies in Conflict Terrorism, 30(12), 1095–1107.

Joosen, K., & Slotboom, A. M. (2015). Terugblikken op de aanloop: Dynamische voorspellers van perioden van detentie gedurende de levensloop van vrouwelijke gedetineerden in Nederland. Tijdschrift voor Criminologie, 57(1), 84–98.

Kakar, S. (1996). The colors of violence: Cultural identities, religion, and conflict. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

King, M., & Taylor, D. M. (2011). The radicalization of homegrown jihadists: A review of theoretical models and social psychological evidence. Terrorism and Political Violence, 23(4), 602–622.

Klausen, J. (2015). Tweeting the Jihad: Social media networks of Western foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 38(1), 1–22.

Koomen, W., & van der Pligt, J. (2009). Achtergronden en determinanten van radicalisering en terrorisme. Tijdschrift voor Criminologie, 51(4), 345–359.

Kruglanski, A. W., Gelfand, M. J., Bélanger, J. J., Sheveland, A., Hetiarachchi, M., & Gunaratna, R. (2014). The psychology of radicalization and deradicalization: How significance quest impacts violent extremism. Political Psychology, 35(S1), 69–93.

Kruglanski, A. W., Jasko, K., Chernikova, M., Dugas, M., & Webber, D. (2017). To the fringe and back: Violent extremism and the psychology of deviance. American Psychologist, 72(3), 217–230.

Li, Q., & Brewer, M. B. (2004). What does it mean to be an American? Patriotism, nationalism, and American identity after 9/11. Political Psychology, 25(5), 727–739.

Ljujic, V., van Prooijen, J. W., & Weerman, F. (2017). Beyond the crime-terror nexus: Socio-economic status, violent crimes and terrorism. Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice, 3(3), 158–172.

Makarenko, T. (2012). Foundations and evolution of the crime–terror nexus. In F. Allum & S. Gilmour (Eds.), Routledge handbook of transnational organized crime (pp. 252–267). New York: Routledge.

McCauley, C., & Moskalenko, S. (2008). Mechanisms of political radicalization: Pathways toward terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence, 20(3), 415–433.

Moghaddam, F. (2005). The staircase to terrorism: A psychological exploration. American Psychologist, 60(2), 161–169.

Neuberg, S. L., & Cottrell, C. A. (2006). Evolutionary bases of prejudices. In M. Schaller, J. A. Simpson, & D. T. Kenrick (Eds.), Evolution and Social Psychology (pp. 163–187). New York: Psychology Press.

Neuberg, S. L., Kenrick, D. T., & Schaller, M. (2011). Human threat management systems: Self-protection and disease avoidance. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(4), 1042–1051.

Pare, P. P., & Felson, R. (2014). Income inequality, poverty and crime across nations. The British Journal of Sociology, 65(3), 434–458.

Ranstorp, M. (1996). Terrorism in the name of religion. Journal of International Affairs, 50(1), 41–62.

Riek, B. M., Mania, E. W., & Gaertner, S. L. (2006). Intergroup threat and outgroup attitudes: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10(4), 336–353.

Sageman, M. (2004). Understanding terror networks. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Sageman, M. (2008). The next generation of terror. Foreign Policy, 165(March/April), pp. 36–42.

Schmid, A. P. (2004). Frameworks for conceptualising terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence, 16(2), 197–221.

Schmid, A. P. (2011). The Routledge handbook of terrorism research. London/New York: Routledge.

Schmid, K., & Muldoon, O. T. (2015). Perceived threat, social identification, and psychological well-being: The effects of political conflict exposure. Political Psychology, 36(1), 75–92.

Schmitt, D. P., & Pilcher, J. J. (2004). Evaluating evidence of psychological adaptation: How do we know one when we see one? Psychological Science, 15(10), 643–649.

Shadid, W. A. (1991). The integration of Muslim minorities in the Netherlands. International Migration Review, 25, 355–374.

Staub, E. (2004). Understanding and responding to group violence: Genocide, mass killing, and terrorism. In F. M. Moghaddam & A. J. Marsella (Eds.), Understanding terrorism:Psychosocial roots, consequences, and interventions (pp. 151–168). Washington: American Psychological Association.

Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (2005). In J.F. Dovidio, Glick, P., & Rudman, L.A. (Eds.) Intergroup relations program evaluation. On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport (pp. 431–446). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Stephan, C. W., & Stephan, W. S. (2013). An integrated threat theory of prejudice. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp. 33–56). New York/London: Psychology Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey: Brooks/Cole.

Van Ham, T., Hardeman, M., Van Esseveldt, J., Lenders, A., & Van Wijk, A. (2018). A view on left-wing extremism: An exploratory study into left-wing extremist groups in the Netherlands. Den Haag: WODC.

van Prooijen, J. W., Krouwel, A. P., & Pollet, T. V. (2015). Political extremism predicts belief in conspiracy theories. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 6(5), 570–578.

Veldhuis, T., & Bakker, E. (2009). Muslims in the Netherlands: Tensions and violent conflict (MICROCON Policy Working Paper 6). Brighton: MICROCON.

Vellenga, S. (2018). Anti-Semitism and Islamophobia in the Netherlands: Concepts, developments, and backdrops. Journal of Contemporary Religion, 33(2), 175–192.

Verkuyten, M. (2018). Religious fundamentalism and radicalization among Muslim minority youth in Europe. European Psychologist, 23(1), 21–31.

Versteegt, I., Ljujic, V., El Bouk, F., Weerman, F., & van Maanen, F. (2018). Terrorism, adversity and identity. A qualitative study on detained terrorism suspects in comparison to other detainees. Amsterdam: NSCR.

Victoroff, J. E., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2009). Psychology of terrorism: Classic and contemporary insights. New York: Psychology Press.

Visser-Vogel, E., de Kock, J., Bakker, C., & Barnard, M. (2018). I have Dutch nationality, but others do not see me as a Dutchman, of course. Journal of Muslims in Europe, 7(1), 94–120.

Weenink, A. W. (2015). Behavioral problems and disorders among radicals in police files. Perspectives on Terrorism, 9(2), 17–33.

Weggemans, D., Bakker, E., & Grol, P. (2014). Who are they and why do they go? The radicalization and preparatory processes of Dutch jihadist foreign fighters. Perspectives on Terrorism, 8(4), 100–110.

Wittendorp, S., de Bont, R., Bakker, E., & de Roy van Zuijdewijn, J. (2017). Persoonsgerichte aanpak Syrië/Irak-gangers. Leiden: Universiteit Leiden.

Zick, A., Pettigrew, T. F., & Wagner, U. (2008). Ethnic prejudice and discrimination in Europe. Journal of Social Issues, 64(2), 233–251.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ljujic, V. et al. (2020). Testing a Threat Model of Terrorism: A Multi-method Study About Socio-Economic and Psychological Influences on Terrorism Involvement in the Netherlands. In: Weisburd, D., Savona, E.U., Hasisi, B., Calderoni, F. (eds) Understanding Recruitment to Organized Crime and Terrorism. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36639-1_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36639-1_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-36638-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-36639-1

eBook Packages: Law and CriminologyLaw and Criminology (R0)