Abstract

Hamlet ellipsis (see Parsons 1997) is a propositionalist account of depiction reports (e.g. Mary imagines/paints a unicorn) that analyzes the object DPs in these reports as the result of eliding the infinitive to be (there) from a CP. Hamlet ellipsis has been praised for its uniformity and systematicity, and for its ability to explain the learnability of the meaning of depiction verbs (e.g. imagine, paint). These merits notwithstanding, recent work on ‘objectual’ attitude reports (esp. Forbes 2006; Zimmermann 2016) has identified a number of challenges for Hamlet ellipsis. These include the material inadequacy of this account, its prediction of unattested readings of reports with temporal modifiers, and its prediction of counterintuitive entailments. This paper presents a semantic save for Hamlet ellipsis, called Hamlet semantics, that answers the above challenges. Hamlet semantics denies the elliptical nature of the complement in depiction reports (s.t. object DPs are interpreted in the classical type of DPs, i.e. as intensional generalized quantifiers). The propositional interpretation of the object DPs in these reports is enabled by the particular interpretation of depiction verbs. This interpretation converts intensional quantifiers into ‘existential’ propositions during semantic composition.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

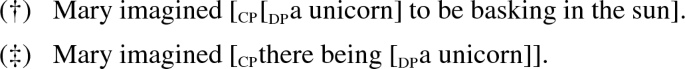

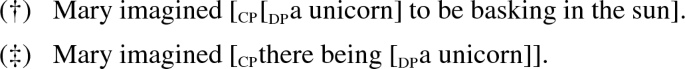

Note that, while depiction reports like (1b) may be “bad English” (to use Quine’s term, see [40, p. 152]), they are still grammatical. To see this, consider the similarly structured report (\(\dagger \)):

The above notwithstanding, we find that reports with gerundive small clause complements like (\(\ddagger \)) are more natural and intuitively provide better paraphrases of reports like (1a). We will present a likely reason for this judgement in Sect. 3.1.

- 4.

Notably, (13a) violates Percus’ Generalization X (see [37, p. 201]). This rule demands that the world/situation variable that a verb selects for must be coindexed with the nearest lambda abstractor above it (in Forbes’ example: with the lambda abstractor that is associated with imagine). On Percus’ account, the de dicto-reading of (1b) is analyzed as (\(*\)), where \(w_{0}\) and \(w_{1}\) range over situations:

- 5.

Below, types are given in superscript. Following standard convention, we let s be the type for indices (i.e. world/time-pairs) or for situations. e and t are the types for individuals and truth-values or truth-combinations, respectively. Types of the form \((\alpha \beta )\) (for short: \(\alpha \beta \)) are associated with functions from objects of type \(\alpha \) to objects of type \(\beta \).

- 6.

In virtue of this interpretation, Hamlet semantics differs from Moltmann’s [31] intensional quantifier analysis of the complements of intensional transitive verbs.

- 7.

We will see in Sect. 4.2 that—given certain constraints—this move still allows depiction verbs to take non-existential quantified DPs in object position.

- 8.

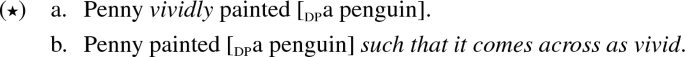

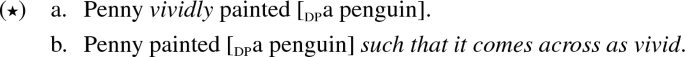

Arguably, modification with vividly works better for imagine than for paint (see (21a) vis-a-vis (\(\star \) a)). In particular, the most natural interpretation of (\(\star \) a) (in (\(\star \) b)) treats vividly as a resultative predicative. I thank an anonymous reviewer for SCI-LACompLing2018 for directing my attention to this issue.

- 9.

- 10.

- 11.

see https://thewire.in/history/russian-revolution-catalysed-array-experiments-art (accessed April 27, 2019).

- 12.

In this respect, our situations are distinct from Kratzer-style situations [20, 21] and Davidsonian events [5], which are both “unrepeatable entities with a location in space and time” (see [25, p. 151]). For Kratzer-style situations, this is reflected in the stipulation that “every possible situation s is related to a unique maximal element, which is the world of s” (see [21, p. 660, Condition 5]).

- 13.

see https://www.nzherald.co.nz/lifestyle/news/article.cfm?c_id=6&objectid=11400740 (accessed April 27, 2019).

- 14.

Arguably, the term internal situation is ambiguous in iterated attitude reports like (55a) (i.e. Ferdinand painted Jacob dreaming of an angel). In (55a), the situation that is denoted by the deepest embedded complement (i.e. the situation denoted by an angel) is internal both w.r.t. the inner verb (i.e. dream) and the outer verb (i.e. paint). The relativization of this situation to the attitude verb (here: the replacement of internal situation by depicted situation) avoids this ambiguity.

- 15.

It is closure under maximal similarity that effects the non-anchoredness of propositional facts.

- 16.

For reasons of simplicity, we hereafter neglect tense in the logical translation of our examples.

- 17.

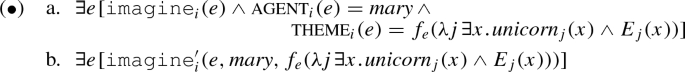

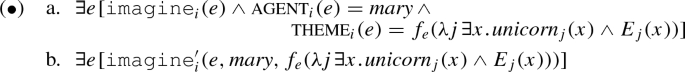

As a result of this event-dependence, the interpretation of (1a) uses two translations of imagine, viz. as a situation-relative predicate of pairs of situations and individuals (i.e. imagine; type s(s(et))) and as a situation-relative predicate of events (i.e. imagine; type s(vt)). One could avoid this ‘dual translation’ by adopting instead the fully-fledged event-interpretation of (1a) (see the Neo-Davidsonian version in (\(\bullet \) a) [3, 35] and the original Davidsonian version in (\(\bullet \) b) [5]). (I thank an anonymous referee for SCI-LACompLing2018 for suggesting the interpretation in (\(\bullet \) a).)

Since the interpretation in (26) is closer in spirit to established semantics for depiction reports (e.g. [49, 50]), we here adopt this interpretation. Readers who prefer the above event-interpretation are free to adopt this interpretation instead. For a compositional implementation of Neo-Davidsonian event semantics, these readers are referred to [4].

- 18.

The semantic deviance of (42) is due to the fact that states (incl. those introduced by be) do not allow for manner modification (see [28]). I thank Sebastian Bücking for providing this reference.

- 19.

An exception to this is Larson [24, p. 232], who labels the discussed class verbs of depiction and imagination.

- 20.

We interpret the difficulty of this endeavor as support for the vivid interpretation of imagination reports.

- 21.

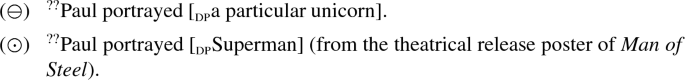

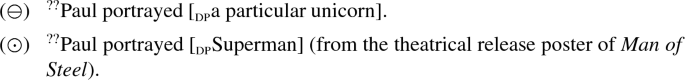

The factivity of portray is supported by the intuitive semantic deviance of reports (e.g. (\(\ominus \)), (\(\odot \))) that report the portrayal-in-i of an individual that does not exist in i:

For ideas about the treatment of such atypical, i.e., non-factive, uses of portray, the reader is referred to our solution to the challenge from concealed iterated attitudes (see Sect. 5.2).

- 22.

Arguably, this analysis would equally serve to answer Challenge 3 for Hamlet ellipsis. (I thank two anonymous referees for SCI-LACompLing2018 for pointing out this possibility.). A similar point can, in fact, be made for Challenges 2 and 4. However, in contrast to (the suitably modified variant of) Hamlet ellipsis, only Hamlet semantics solves Challenges 1 and 5.

- 23.

Thus, Zimmermann [51, p. 435] writes, “for [(17b)] to be true, the picture would not need to imply that there be a real angel—a dream angel would be enough; and obviously the dream angel also suffices to make the sentence [(15a)] true, which would thus be aptly captured by [(17b)].”.

References

Bayer, S.: The coordination of unlike categories. Language 72(3), 579–616 (1996)

Bücking, S.: Painting cows from a type-logical perspective. In: Sauerland, U., Solt, S. (eds.) Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 22, pp. 277–294. ZAS Papers in Linguistics, Berlin (2018)

Carlson, G.N.: Thematic roles and their role in semantic interpretation. Linguistics 22(3), 259–280 (1984)

Champollion, L.: The interaction of compositional semantics and event semantics. Linguist. Philos. 38(1), 31–66 (2015)

Davidson, D.: The logical form of action sentences. In: Rescher, N. (ed.) The Logic of Decision and Action, pp. 81–95. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh (1967)

Devlin, K., Rosenberg, D.: Information in the study of human interaction. In: Adriaans, P., van Benthem, J. (eds.) Philosophy of Information, pp. 685–710. Elsevier, Amsterdam (2008)

Falkenberg, G.: Einige Bemerkungen zu perzeptiven Verben. In: Falkenberg, G. (ed.) Wissen, Wahrnehmen, Glauben, pp. 27–45. Niemeyer, Tübingen (1989)

Fine, K.: Properties, propositions, and sets. J. Philos. Log. 6, 135–191 (1977)

Fine, K.: Critical review of Parsons’ non-existent objects. Philos. Stud. 45, 95–142 (1984)

Forbes, G.: Attitude Problems: An Essay on Linguistic Intensionality. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2006)

Forbes, G.: Content and theme in attitude ascriptions. In: Grzankowski, A., Montague, M. (eds.) Non-Propositional Intentionality, pp. 114–133. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2018)

Goodman, N.: Languages of Art. Hackett Publishing, New York (1969)

Grzankowski, A.: Not all attitudes are propositional. Eur. J. Philos. 23(3), 374–391 (2015)

Grzankowski, A., Montague, M.: Non-propositional intentionality: an introduction. In: ibid. Non-Propositional Intentionality, pp. 1–18. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2018)

Heusinger, K. von: The salience theory of definiteness. In: Perspectives on Linguistic Pragmatics, pp. 349–374. Springer, New York (2013)

Higginbotham, J.: Remembering, imagining, and the first person, 212–245 (2003)

Israel, D., Perry, J.: Where monsters dwell. Log. Lang. Comput. 1, 303–316 (1996)

Kaplan, D.: Demonstratives: an essay on the semantics, logic, metaphysics, and epistemology of demonstratives and other indexicals. In: Almog, J., Perry, J., Wettstein, H. (eds.) Themes from Kaplan, pp. 489–563. Oxford University Press, Oxford (1989)

Karttunen, L.: Discourse referents. In: McCawley, J. (ed.) Syntax and Semantics 7: Notes from the Linguistic Underground, pp. 363–385. Academic Press, New York (1976)

Kratzer, A.: An investigation of the lumps of thought. Linguist. Philos. 12, 607–653 (1989)

Kratzer, A.: Facts: particulars or information units? Linguist. Philos. 25(5–6), 655–670 (2002)

Kratzer, A.: Decomposing attitude verbs: handout from a talk in honor of Anita Mittwoch on her 80th birthday. Hebrew University Jerusalem (2006)

Kratzer, A.: Situations in natural language semantics. In: Zalta, E.N. (ed.) The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 Edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2019/entries/situations-semantics/

Larson, R.K.: The grammar of intensionality. In: Logical Form and Language, pp. 369–383. Clarendon Press, Oxford (2002)

LePore, E.: The semantics of action, event, and singular causal sentences. In: LePore, E., McLaughlin, B. (eds.) Actions and Events: Perspectives on the philosophy of Donald Davidson, pp. 151–161. Blackwell, Oxford (1985)

Liefke, K.: A single-type semantics for natural language. Doctoral dissertation. Tilburg Center for Logic and Philosophy of Science, Tilburg University (2014)

Liefke, K., Werning, M.: Evidence for single-type semantics - an alternative to \(e\)/\(t\)-based dual-type semantics. J. Semant. 35(4), 639–685 (2018)

Maienborn, C.: On the limits of the davidsonian approach: the case of copula sentences. Theor. Linguist. 31, 275–316 (2005)

Maier, E., Bimpikou, S.: Shifting perspectives in pictorial narratives. In: Espinal, M.T., Castroviejo, E., Leonetti, M., McNally, L., Real-Puigdollers, C. (eds.) Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 23, 91–105. https://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/Tg3ZGI2M/Maier.pdf

McCawley, J.D.: On identifying the remains of deceased clauses. Lang. Res. 9, 73–85 (1974)

Moltmann, F.: Intensional verbs and quantifiers. Nat. Lang. Semant. 5(1), 1–52 (1997)

Moltmann, F.: Intensional verbs and their intentional objects. Nat. Lang. Semant. 16(3), 239–270 (2008)

Montague, R.: On the nature of certain philosophical entities. Monist 53(2), 159–194 (1969)

Montague, R.: Universal grammar. Theoria 36(3), 373–398 (1970)

Parsons, T.: Events in the Semantics of English. The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA (1990)

Parsons, T.: Meaning sensitivity and grammatical structure. In: Broy, M., Dener, E. (eds.) Structures and Norms in Science, pp. 369–383. Springer, Dordrecht (1997)

Percus, O.: Constraints on some other variables in syntax. Nat. Lang. Semant. 8, 173–229 (2000)

Pustejovsky, J.: Where things happen: on the semantics of event localization. In: Proceedings of the IWCS 2013 Workshop on Computational Models of Spatial Language Interpretation and Generation (CoSLI-3) (2013)

Pustejovsky, J.: Situating events in language. Conceptualizations of Time 52, 27–46 (2016)

Quine, W.V.: Quantifiers and propositional attitudes. J. Philos. 53(5), 177–187 (1956)

Ross, J.R.: To have have and to Not have have. In: Jazayery, M., Polom, E., Winter, W. (eds.) Linguistic and Literary Studies, pp. 263–270. De Ridder, Lisse, Holland (1976)

Sæbø, K.J.: ‘How’ questions and the manner-method distinction. Synthese 193(10), 3169–3194 (2016)

Sag, I., Gazdar, G., Wasow, T., Weisler, S.: Coordination and how to distinguish categories. Nat. Lang. Linguist. Theory 3(2), 117–171 (1985)

Schwarz, F.: On needing propositions and looking for properties. In: Proceedings of SALT XVI, pp. 259–276 (2006)

Schlenker, P.: A plea for monsters. Linguist. Philos. 26(1), 29–120 (2003)

Stainton, R.J.: Words and Thoughts: Subsentences, Ellipsis and the Philosophy of Language. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2006)

Stephenson, T.: Vivid attitudes: centered situations in the semantics of ‘remember’ and ‘imagine’. In: Proceedings of SALT XX, pp. 147–160 (2010)

Umbach, C., Hinterwimmer, S., Gust, H.: German ‘wie’-complements: manners, methods and events in progress (submitted)

Zimmermann, T.E.: On the proper treatment of opacity in certain verbs. Nat. Lang. Semant. 1(2), 149–179 (1993)

Zimmermann, T.E.: Monotonicity in opaque verbs. Linguist. Philos. 29(6), 715–761 (2006)

Zimmermann, T.E.: Painting and opacity. In: Freitag, W., et al. (eds.) Von Rang und Namen, pp. 427–453. Mentis, Münster (2016)

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank three anonymous referees for SCI-LACompLing2018 for valuable comments on an earlier version of this paper. The paper has profited from discussions with Sebastian Bücking, Eugen Fischer, Friederike Moltmann, Frank Sode, Carla Umbach, Dina Voloshina, Markus Werning, and Ede Zimmermann. The research for this paper is supported by the German Research Foundation (via Ede Zimmermann’s grant ZI 683/13-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Liefke, K. (2020). Saving Hamlet Ellipsis. In: Loukanova, R. (eds) Logic and Algorithms in Computational Linguistics 2018 (LACompLing2018). Studies in Computational Intelligence, vol 860. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30077-7_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30077-7_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-30076-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-30077-7

eBook Packages: Intelligent Technologies and RoboticsIntelligent Technologies and Robotics (R0)