Abstract

The chapter presents a theoretical overview of the participatory practice within non-profit rental housing cooperatives and the basic operational principles behind them. It stresses the importance of the societal perspective of such practice, with regard to individual benefits of the residents as well as the potential for a fairer and sustainable urban development on a broader scale beyond the provision of housing. Housing cooperatives form an integral part of housing provision systems in various parts of the world. While their organisational models may vary considerably, all generally abide to the organisational and normative principles of cooperatives, which entail the basics of participatory practices on more than just one level. They promote active citizenship through direct democratic principles in housing provision and the formation of housing policies. Furthermore, cooperatives promote member participation through all stages: planning, construction and later in management of the residents. Such organisational model stresses the importance of good communication skills that allow cooperation and consequently give rise to social capital and trust among members.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

6.1 Institutional Framework of the Housing Question—The Right to Housing or Housing as a Commodity?

The rise of alternative housing models should primarily be understood as a response to “historically and institutionally concrete situations of need satisfaction in a certain territory” (Moulaert and Nussbaumer in Lang and Roessl 2011, p. 8). In other words, alternative housing models emerged from the active response to growing issues of the housing market speculations on one hand and the possibility of active citizenship practices on the other. It has become evident that most of the market-oriented mechanisms could not meet the citizens’ demand for housing around the globe. In opposition to the individualistically oriented solutions of the housing problem, we are now facing the emergence and revival of the so-called alternative initiatives and community-based approaches to housing provision. Examples of such models are housing cooperatives, co-housing, self-development, grouped housing, etc. (Zimmermann 2014), which are usually related and are present in various forms. They all nevertheless stress the importance on the empowerment of individuals through participation in autonomous yet collective activity.

Community-based and participatory rental housing, organised in cooperative manner, does not merely bring new legal and economic frames of housing provision. It thrives on democratic principles based on inclusive participation of all stakeholders it concerns. Such principles reflect a step beyond mere housing provision and represent a new lifestyle with socially oriented normative frames.

(Future) residents and members of cooperatives are ideally included in all stages of the housing provision: designing, building, managing and cohabiting. Community-oriented cooperatives also provide social security by developing a sense of belonging to a certain group or place. Postmodern cooperative models stress the importance of everyday encounters and reciprocity among members, thus augmenting social cohesion. They “often explicitly include weaker social groups and have inter-cooperative resources” (Droste 2015, p. 11).

Community-based models provide a form of economic and social stability that is based on reciprocity and strong community bonds. They come in many forms, for the form is subjected to the members’ needs and preferences. They bring an alternative perspective to the understanding of housing as a basic human right. Community-oriented housing models redefine the understanding of the housing question and enable empowerment through uniting individuals with similar ideals and interests.

6.2 The Rise of Participatory Approaches in Housing: Impact on Citizenship Empowerment, Social Capital and Social Cohesion

According to Shills (Iglič 2004), empowerment and civic engagement are measured through the quality of network relationships and the citizens’ attitudes regarding the idea of a functional society. The possibility of individuals’ civic engagement allows their integration into a common moral and normative frame, thus adding to social integration and consequently a stable democratic governance with participatory potential. Participation in the public sphere ideally seeks the involvement of all stakeholders and other civic organisations according to the principles of consensus. It is an integral part of the concept of governance that OECD (in Garcia 2006, p. 750) describes as “the process by which citizens collectively solve their problems and meet society’s needs”, using institutional tools as an instrument for achieving common goals.

Participatory approaches to housing enable residents to integrate their own needs, preferences and values into their future living environment. Moreover, it sets grounds for empowerment and reflection of active citizenship by including all residents in the later processes of building management and strengthening of direct neighbour interactions without intermediaries. Direct resident participation in day-to-day practices represents the bottom-up culture of governance, which depends upon strong community bonds that enable collective action (Garcia 2006).

Community-oriented participatory housing usually involves sharing space and living costs of its residents while also offering public space and activities to broader community on a neighbourhood level. It brings a shift from an individualistic, core family-oriented model of housing provision to higher sociability on all levels. By turning individuals into active members of society, participatory-based planning not only facilitates internal processes of housing management and relations, but also contributes to strengthening the sense of community and responsibility for its well-being (Droste 2015). The feeling of belonging to a certain community triggers reflexive and considerate behaviour towards other members (Phillips and Filipovič 2007). It also raises social capital of individuals and their trust levels—the two main features of civic engagement and efficient planning policy.

According to Bourdieu (1986), social capital can be defined as an aggregate of actual and potential assets of a certain social network that individual is a part of. The networks depend on the maintenance of acquaintanceships on different institutional levels, reciprocity of connections and a certain level of solidarity among members. Similarly, Coleman (1988) defines social capital as a type of a resource, available to individuals through network connections. Furthermore, he describes social capital as a productive capital that enables achievement of certain goals that could not be reached without the use of common network resources. Therefore, social capital can be defined through social networks, reciprocity and trust among members. It is usually measured through active membership in various voluntary associations, religious institutions, political parties and the level of trust (Schuller 2001). “Social capital enhances the benefits of investment in physical and human capital” (Putnam in Kearns and Forrest 2001, p. 2137). It refers to features of social organisation such as networks, norms and trust. All of these features facilitate coordination and cooperation of members for their mutual benefit.

Social capital offers the potential of mutual benefit that comes from the “culture of trust”, which reduces individuals’ inclination towards egoistic opportunism. The greater the feeling of belonging to a certain community, the higher is the moral obligation to conform to the normative rules. The obligation derives from the mutual belief that other members do not want to endanger the relationship and long-term benefit potential for the sake of the short-term individual benefit. “Community cooperatives do not only focus on a member’s advantage, but act on behalf of some collective identity” (Lang and Roessl 2011, p. 1).

Community-oriented housing initiatives’ impact on the strength of individuals’ social bonds could also be described through basic community versus society (gemeinschaft and gesellschaft) dichotomy that was first introduced by Tonnies more than a century ago. The theory explains the importance of common commodities that are shared by the members of a community and the higher level of interdependence they bring. Smaller social structures with a higher level of interdependence and consequently stronger social bonds show a higher level of social cohesion, which manifests on daily basis in day-to-day encounters and activities. Members of a community—in contrary to the members of a broad notion of society—share direct ownership of basic goods. Shared ownership of the latter seems to be a crucial factor for better cooperation and successful goal achievement (Filipovič 2007). The community-oriented rental housing cooperative is a fine example of shared ownership since the members of the cooperative never own their apartment as a whole, but they own their share of the cooperative as a whole. Such an organisational structure demands certain participatory and democratic approaches to building management (in all stages), which maintains a higher level of social capital of its members. It opens a window for a direct civic engagement in participatory processes that are otherwise limited by neoliberal, top-down models of governance and housing provision in particular. Participatory housing practices in their various forms always involve the “inhabitants in the production or co-production of their living environment and in the day-to-day, routine management of the property they occupy” (D’Orazio and Zimmermann 2014, p. 1).

However, a set of clear and universal guidelines of participatory processes within the community need to be defined in order to grasp the participative management potential of community-oriented housing cooperatives. According to Williams (2006), a full and direct resident involvement in decision-making process does not always appear to be as productive as the theories of participatory decision-making policies may suggest. Case-to-case-based decision-making processes almost inevitably raise conflict of interest, no matter the common normative frame of the community members. As the study has shown (Williams 2006), the conflicts within the community may arise from as mundane questions as one of the furniture designs in the common area, resulting in resident’s complete withdrawal from decision-making process or even the community as a whole. The functional community therefore needs to set rules on what, how and where certain decisions are made, without tiring residents with never-ending meetings on the one hand or excluding them from relevant decision-making process on the other. In other words, even participative decision-making processes and community management have certain disadvantages. Participative management should therefore be carefully planned, which may sometimes be easier said than done. However, the potential for productive social interactions usually rises with organisational maturity and higher trust level, thus through gaining direct experience from a long-term participatory practice.

6.3 Rental Housing Cooperative Model

Cooperative is an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise. Co-operatives are businesses owned and run by and for their members. Whether the members are the customers, employees or residents they have an equal say in what the business does and a share in the profits. (International Co-operative Alliance 2018)

A cooperative is an institutional form that connects individuals with certain needs into a community with shared values. It is essentially a member-owned and democratically controlled enterprise that prioritises members’ needs over the mere business profit of the organisation. As such, cooperatives are an important bearer of community-oriented values originating in direct democratic participation, solidarity and principles of self-help and self-responsibility. There are numerous forms of cooperative enterprises and communities around the globe, differentiated according to members’ specific interests and the sociopolitical milieu.

Regardless of structural and operational diversity, all cooperatives should follow seven basic principles that frame cooperative values into practical guidelines. As it will be seen, the principles advocate direct democracy and constant active member participation. They furthermore encourage cooperation and integration of other non-members. According to the International Cooperative Alliance (2018), the principles are as follows:

-

1.

Voluntary and open membership:

Cooperatives are voluntary organisations, open to all individuals that are willing to accept the membership responsibilities, without gender, social, racial, political or religious discrimination.

-

2.

Democratic member control:

Cooperatives are democratic organisations controlled by their members, who actively participate in decision and policy-making by the one member—one vote principle. Members also elect representatives who are accountable to other members.

-

3.

Member economic participation:

Members contribute equitably to the cooperative capital that is controlled democratically. Surpluses are allocated into further cooperative development, support of other member approved activities or social justice among members.

-

4.

Autonomy and independence:

Cooperatives are autonomous and self-help organisations, internally controlled by members. When entering into agreements with external actors, cooperatives act in terms that ensure democratic member control and other basic cooperative principles.

-

5.

Education, training and information:

Cooperatives invest in further member education in order to ensure self-responsible organisation activity. Knowledge transfer is considered as a safeguard of a future cooperative development.

-

6.

Cooperation among cooperatives:

By forming cooperative alliances, a certain support network is established. Alliances strengthen cooperative movement and provide grounds for autonomous development on local, national and regional level.

-

7.

Concern for community:

Cooperatives should never operate in exclusive manners. Spreading cooperative values, cooperatives should aspire sustainable development of the whole community, leaving a positive impact on a broader scale. They should never exist solely for the benefit of their members but should seek ways of collaborating with other sectors.

Housing cooperative models are just one of the cooperative forms with the specific goal of housing provision for its members. Just as any other form of a cooperative, a housing cooperative is a communally oriented way of problem solving. As such, it has been used for more than a century around different parts of the world. Nonetheless, it has regained popularity in recent decades as a response to the growing housing issues that emerge from market speculations on the one hand and weak welfare state policies on the other. The primary goal of housing cooperatives is generally the provision of affordable housing and not making profit through the commodification of dwellings. Considering this, housing cooperatives are crucial to the public interest and thus present a more sustainable model of housing provision. According to Somerville (2007), they are considered an important part of the so-called third sector, which represents a sphere in between the private and the public. Following the basic cooperative values and norms, housing cooperatives operate on a community level—surpassing mere housing provision, bridging the capitals of the member residents and encouraging participatory principles of building and cohabiting.

Residents of a rental housing cooperative are primarily members of a cooperative, contrary to being an individual housing owners. Such model stimulates participatory approaches—not solely to planning, but also later in management of the building.

Direct resident participation in the planning and management of a neighbourhood can be seen as a fundamental principle of cooperative housing organisations, which distinguishes them from the other housing providers. It is a consequence or the multiple roles of a cooperative member as owner, manager and a client of the housing organisation. The relationship between executive board member and ordinary member is non-hierarchical and personalised, as they are immediate neighbours in the same housing estate. (Lang and Novy 2014, p. 1754)

6.3.1 La Borda—Introducing a Housing Cooperative Model in Barcelona, Spain

Since the global financial crisis and the burst of the Spanish housing bubble, Spanish economy and particularly its housing sector have been suffering grave consequences, such as increasing pressure on households and impact on the financial, labour and housing markets. But the crisis in 2008 also created opportunities in the housing market for alternative housing schemes. That was also the starting point for the birth of the housing cooperative La Borda in district Can Batlló in Barcelona in 2012. It developed without the support of the city, although in 2015, La Borda did sign a contract with the city of Barcelona for the lease of land. In parallel with the housing crisis, there was an emergence of a strong social economy, particularly a cooperative movement, and the resurgence of a strong neighbourhood movement, which aimed to develop an alternative model that did not rely on the traditional market-driven housing agents (Cabré and Andrés 2017). Two years after the cooperative began to operate, it already presented drawings, a model, a preliminary study of the building and a draft of the statutes for a future cooperative to the community. The project was open to anyone willing to participate (Garcia 2015).

The reference model for La Borda is the Danish model, also known as the Andel Model, which is based on a private initiative of non-profit cooperatives that develop and manage housing for their members who pay the returnable entry fee. The members of the cooperative participate in all decision-making processes through an assembly. One of the more important characteristics of the model is its non-speculative nature that considers housing as a basic right rather than a commodity (Cabré and Andrés 2017).

Though the mentioned features already imply the participatory- and community-based approach of La Borda, there are several components that are derived from these features. Since La Borda is a non-profit housing cooperative, autonomous and democratic, all its members govern the cooperative, define strategies, as well as approve and monitor the projects related to the development process according to their needs. Participation has been organised through various work groups, workshops and discussions at the General Assembly. La Borda also has a technical support group for proposals (Cabré and Andrés 2017).

In addition to its self-management, La Borda also relies on its members as volunteers for the construction of the building, which reduces the cost of building and enables a higher control of the project. All these features strengthen community life (Cabré and Andrés 2017).

Furthermore, La Borda encourages community life through its communal living model, which includes shared common facilities and spaces that encourage interaction between residents. These spaces are laundry, kitchen, living room, guest flat, multipurpose room, health and care, bicycle parking, storage, shared objects and tools and a co-working space. The first common and most important space discussed was the laundry service room. Its planning consisted of three phases: (1) presenting the service, (2) encountering the service, (3) selecting a scenario (Garcia 2015). Only to line up three scenarios took them half a year of discussions in assemblies and commissions, and a few more to choose which scenario to pilot. They took into account the results of the questionnaire of the future inhabitants and two types of management—self-managed or externalised and ecological view, etc. (Garcia 2015).

Common spaces are meant to serve as meeting rooms for Con Batlló’s neighbourhood movement, which involves concern for and participation of community itself. Another characteristic of the cooperative is the focus on sustainability in both low environmental impact of the construction project and the sustainable usage of the building. Both promote sustainable development and reduce the potential damage for the residents and wider community. La Borda is also based on member economic participation, specifically social and cooperative economy (Cabré and Andrés 2017).

6.3.2 Mehr Als Wohnen—A Broad Community-Oriented Project in a Strong Housing Cooperative Network and Supportive Environment of the Zurich Municipality, Switzerland

While La Borda is a younger cooperative and its single building will presumably be built 2018, Mehr als wohnen (Eng. More than Housing; hereinafter MAW) is a much more extensive project situated in Hunziger, north of Zurich. The project began in 2007, when the City of Zurich and its housing cooperatives celebrated the centenary of government support for cooperative housing construction using the slogan “100 years of more than housing”. Intensive discussions about the future of housing that followed the festivities led to the founding of the building cooperative MAW, which involved the financial participation of 55 Zurich housing cooperatives and the City of Zurich itself (Borowski 2016). Its nature of establishment therefore already foresaw the legacy of democratic membership, environmental care, community building, etc.

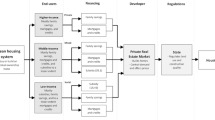

MAW is an example of an open development process that includes collaboration between professionals from different backgrounds by engaging the public, private and educational sector with additional involvement of the end-users. The latter assures that the project corresponds to the citizens’ needs and new ideas. The project development took into account the benefits of early participation processes which enable better commitment to the project and a higher content of the actual users (Purtik et al. 2016).

The project development was based on a working group’s model that favours an inclusive participative and democratic decision-making process. Four working groups were established as follows:

-

1.

Thematic groups for utilisation of the neighbourhood, economy, ecology and technology, which had monthly meetings that involved 50 members of the founding cooperatives and MAW staff;

-

2.

so-called echo rooms which happened twice a year were open to the public, had an external moderator and discussed sustainable construction, building technologies and energy, use of ground floors and volunteering;

-

3.

volunteers of informal working groups and collaborative partners working on complementary currency, contract farming, sustainability in Hunziker Areal, regional sourcing, urban farming and living with the elderly;

-

4.

neighbourhood groups which met monthly and worked on complementary currency, public library, outdoor areas, swap area, regional vegetable sourcing (Purtik et al. 2016). In addition to the working groups, regular public forums were also held. This so-called echo rooms initiated dialogue with the broader public and invited external actors, such as universities, schools and foundations (Purtik et al. 2016).

Today, the cooperative is comprised of 13 buildings with 395 residential units and additional various non-residential premises, community rooms and green spaces (Purtik et al. 2016). There are 35 retail spaces and shared care and community facilities. MAW is a home for around 1200 residents and 150 employees that live and work across the precinct (McMaster 2016):

A series of subsidies are offered to low-income earners, and 10% of the apartments are allocated to charities and not-for-profits, including an orphanage. The result is a development that includes a mixture of people, ranging from recently settled refugees to middle income professionals.

6.4 Effects of the Participatory Cooperative Housing Model on Neighbourhoods, States and Societies

6.4.1 Cooperative Schools of Democracy

The essence of a cooperative is to fulfil the needs and wishes of its members. In order to achieve this goal, each member has to continually reaffirm his or her wishes through the process of participatory democracy. Participation in decisions which impact one’s life through their housing brings more satisfaction with the created living environment and more security with the knowledge that nothing can be decided outside this process. The principle of participatory democracy is or at least should be included in every housing cooperative, and therefore, cooperatives can be seen as schools of democracy and active citizenship with the crucial emphasis on solidarity and acting for the good of the whole community, not just for the benefits of an individual (Sørvoll and Bengtsson 2018). The cooperative principle “one member—one vote” can therefore be seen as a process of reviving the education and socialisation in political engagement.

Members and neighbourhood residents gain more political power when they are connected to a housing cooperative. Cooperatives encourage citizen participation, which empowers people who otherwise would not be the decision-makers, by Arnstein’s definition: “it is the means by which they can induce significant social reform which enables them to share in the benefits of the affluent society” (1969, p. 216). In further promoting their chances of becoming involved in decision-making and influencing their neighbourhood and their cities, cooperatives can play an important role. “Participation in housing projects has also been found to play an important role in empowering beneficiaries or community members to become part of the general political process and to have a voice in decisions that shape the community” (Davidson et al. 2007, p. 102). They can significantly change the position of an individual by backing them with their social capital and influence in the local community and its institutions. It can provide the much-needed access to powerful actors and government bodies. Moreover, if the residents do not want to get directly involved or do not have the means to, housing cooperatives have been noted to take the position of intermediaries between residents and decision-making institutions or actors. Lang and Novy (2014, p. 1745) point to the case of Vienna and argue that the connection with the cooperative in the position of intermediary allows “residents to obtain social capital which links them to decisive resources and decision-making”.

6.4.2 Replacing Public Institutions?

As already mentioned, contemporary alternative housing models were developed mostly because the market failed to provide enough adequate housing, and also as an answer to the rise of housing speculations. In many ways, cooperatives can be seen as acting against the market logic and speculation, with their main aim of fulfilling members’ needs rather than accumulating capital, and with the specific form of collective ownership and management. They have been known to provide much-needed apartments (especially to low- or middle-income households) when the market and the state failed to do so. That is why many of the contemporary housing cooperatives developed in a time of crisis of the housing market, as we saw in the case of La Borda. However, the spread of cooperative housing can be seen in a negative context: as outsourcing the duties and responsibilities that traditionally belonged under the auspices of the government of cities and states.

Lang and Novy (2014, p. 1744) observed that cooperative housing often tries “to fill the gap left by the withdrawal of the state in providing affordable housing”. Therefore, low-income cooperative housing projects can be seen as substituting social housing, within the frame of the neoliberal shrinking of the state and favouring the capital’s needs over the needs of the people. These projects, which are said to fill in the resources previously provided by public institutions, often involve some level of civic participation and voluntarism and “can also have the potential to serve as a resource for cushioning the outsourcing of former (local) state responsibilities in neo-liberalising cities” (Rosol 2016, p. 86).

This political strategy has been marked with the name “roll-back neoliberalism”. Its main aim was to lessen the extent and influence of the state and its institutions in order to make way for the spread of private enterprise and competitive logic even in providing for the most essential human needs. In the field of the housing sector, this is escorted by the privatisation of public housing and land, deregulation, and supporting private real-estate developers and their profits (Peck and Tickel 2007). All of which tend to make housing less affordable.

In times when welfare states are shrinking and the position of the most vulnerable parts of the population is worsening, the role of the voluntary sector increases. The voluntary sector tries to fill in the withdrawal of resources and services and replace them, which is also attractive to politicians who are facing budgetary cuts. Although this may be seen as a good thing—offering services to people in need—it is also legitimising the shrinking of public institutions and budgetary cuts. In these circumstances “community participation in the public service provision is not necessarily an emancipatory claiming of rights by citizens anymore or only but can instead be understood as part of a distinct political rationality that aims at passing state responsibilities on to civil society” (Rosol 2016, pp. 86–87). In this regard, housing cooperatives can be seen to lessen the hits of neoliberalism on the welfare state and therefore on public housing by considering the needs of a community, participating with its members and providing much-needed affordable apartments, all of which used to be the work of governmental institutions.

But neoliberalism does not focus solely on shrinking of the state, it is more accurate to describe it as a transformation of the state and its functions. “New state forms, new models of regulation, new regimes of governance, with the aim of consolidating and managing both marketization and its consequences” (Peck and Tickel 2007, p. 33) are what most characterises the process of roll-out neoliberalism. In circumstances where the former institutions and structures pull back, new structures emerge. As a part of the new forms of governance developed the so-called community governance, which is best described as a hybrid between the neoliberal characteristic of self-reasonability and active citizenship. Community is seen as the ideal instrument for serving the needs of local residents because of the shared value system of its members, which also implies the trust of every member that his contributions to the community will benefit every member individually as well as the community as a whole. Therefore, it is believed that community governance does not only reduce the costs for the public institutions, but also provide a better and more accepted policy (Adams and Hess 2001). In this form of governance, “communities are then expected to look to their own means of governance to be able to survive” (O’Toole and Burdess 2004, p. 434).

Another way in which governmental bodies try to outsource their services is through public–private partnership schemes. Mehr Als Wohnen is a project that grows on the basis of private–public partnership, as are many other housing cooperatives. In order to provide affordable and quality apartments, it is in some cases necessary to gain some kind of support from the state. In the case of Mehr Als Wohnen, public support takes the form of a renting lease for the land with a symbolic rent, property rights, subsidies and public guarantees. As Barcelona or Spain do not yet have a system in place to help develop housing cooperatives, La Borda had to find significant other sources that were prepared to support the project. For this, they relied on cooperation with cooperative for financial services Coop57 and on the solidarity, social finance and social impact founding.

Housing cooperatives fit very well in the scheme of neoliberalism. Although their intention is to fulfil the needs of its members and encourage a sense of belonging through community building, the negative side effect is that they can also be seen as an instrument for the “outsourcing of former local state responsibilities for public services and urban infrastructure” (Rosol 2016, p. 85). In this context, they help legitimise the cuts to the welfare state by encouraging voluntarism, active participation and community building. However, there still seems to be some potential for cooperatives to grow out of this context if citizen participation in housing cooperative leads to a redistribution of power, not just on the level of the community, but broader—on the level of the city or the state.

Real citizen participation is characterised by a redistribution of power, which can bring citizens who were previously excluded from the political sphere into positions of power. In order to achieve this, housing cooperatives need to “delegate power to residents and, at the very top, give them control of the decision-making process and the distribution of resources, such as participatory budgeting efforts today” (Smith 2016, p. 31). If they succeed, they can help shift the neoliberal agenda and have an influence on the political content (Elwood 2002). But if housing cooperatives do not focus on their members, the danger is that they become much more oriented simply towards management and can start to resemble corporate establishments, as has happened to some housing cooperatives in Vienna (Lang and Novy 2014).

6.4.3 Housing Cooperatives as Gentrifiers or Regulators of the Rental Housing Market

Housing cooperatives, as previously established, focus on fulfilling their members’ needs. However, based on the seventh cooperative principle, the concern for well-being and satisfaction is not limited just to the narrow community of the cooperative’s members, but also on the broader local community. One of the goals of housing cooperatives is therefore improving the living conditions of all the residents in the neighbourhood where the housing cooperative is located. This is to be achieved through participation on the neighbourhood level, which provides information about the potential future projects that could improve the residents’ everyday lives. La Borda, actually deriving from the Can Batlló neighbourhood movement, is a good example of a cooperative directly addressing the needs of its immediate surroundings and the broader neighbourhood as the local community was involved in the design process from the very beginning and certain spaces within the building will be available for direct use of that same community.

Housing cooperatives can play a substantial role in regulating the renting housing market as a part of the non-profit housing sector. If the non-profit sector becomes big enough—has a similar presence in the share of the market and “in the market segments where profit providers operate” (Kemeny et al. 2005, p. 858)—that it can compete with the private, profit-seeking housing sector, the former becomes a sort of regulator of the market. Non-profit housing strives for quality apartments at affordable prices—the rent is usually set to cover the costs and any surplus is then reinvested in either sustaining the dwellings as they are (mainly repairs) or in improving them. By forgoing profits and therefore offering cheaper housing, the non-profit owners attract more renters. If the profit housing providers want to compete with the non-profit providers, they also have to lower their rents. Furthermore, “the non-profit sector may also offer better quality dwellings and greater security of tenure, which could force the profit sector to match the offer, thereby reducing the need for regulation” (Kemeny et al. 2005, p. 858). In most places where cooperatives work, the presence of non-profit providers is not strong enough to really have a regulatory influence. The two examples (where the cooperative housing is also very strong) might be found in Zurich and Vienna, where the profit providers have to match the offers of the non-profit providers in order to be competitive. But this may quickly spread to other places. The cooperative housings are rising in many European states are just now, and once the models are established, the housing cooperative sector can grow rapidly. La Borda is a pilot project in Barcelona, but even before the end of the construction phase, new housing cooperative projects are already in the making.

Housing cooperatives and similar participatory projects can have a great influence on the neighbourhood through various community-lead participatory projects, but that can also come with a downside—if the living standards in the neighbourhood substantially improve, it will not be long before the real-estate market prices rise and the process of gentrification takes place. The people who contributed to improving the neighbourhood are consequently often forced to leave their homes for the benefit of making profits by others. As Rosol puts it (2016, p. 90):

… if strategies to improve living conditions in a neighbourhood are not combined with mechanisms that prevent displacement of residents and keep housing affordable, even the most well-meaning projects can become the engine of gentrification.

6.5 Conclusion

Mehr als Wohnen, which would be roughly translated to more than housing, seems to be the perfect name for a cooperative housing establishment; not just for the housing and work complex in Zurich, but for every rental housing cooperative that abides by the seven cooperative principles. This distinct form of housing provision becomes more than a residence precisely because it entails participation on every stage of development and use. It is the participation of residents in ownership and democratic management of the cooperative that makes them more economically and socially secure regarding their dwelling. Participatory approach to developing and managing enables residents to integrate their needs, wishes and preferences into their dwellings and common spaces. However, participation in housing cooperatives most often surpasses the mere essentials of housing and is encouraged in other aspects of living.

Through participation, housing cooperatives encourage the development of a community that connects its members, but also neighbourhood residents. Housing cooperatives often offer public spaces, services and activities to non-residents, which can substantially improve neighbourhood life and encourage sociability on all levels. By developing a sense of belonging to a certain community, people become more responsible for their well-being. Through the process, they gain more social capital, build on trust and therefore feel more socially secure. Participation on the level of the cooperative can also encourage them to get involved in participatory projects and decision-making on the level of the neighbourhood or even the city. In summary, living in a democratic participatory housing project can simulate further citizen activity.

Even though participatory practice appears to be beneficial for social interactions, a question of successful and adequate housing management should not be neglected. Participatory approaches to building and community design or management do not always meet the variety of resident preferences per se. Consequently, a high level of frustration might appear, resulting in members’ withdrawal from communal social interaction. Although community-oriented ways of living may bring a significant potential for one’s social reflexivity, they can also be tiresome and time consuming. This leads to the conclusion that participatory processes need to be carefully planned and managed, even though they may seem to be the single most spontaneous practice within equitable communities.

The negative aspects that can emerge with participatory housing provision on a systemic level have also been discussed. First, renting housing cooperatives are more often than not based on voluntary work from organisers and its residents and are generally subject to the public–private partnerships. Therefore, it seems that they fit into the neoliberal strategy of privatisation of traditionally public domains, cutting public funding, shrinking the state and externalising public services. This forces people and their communities to become self-reliable and can leave them without the needed services and support. Second, by improving the neighbourhoods in which the cooperatives are embedded, they can contribute to the process of gentrification, which threatens the local population.

When talking about the beneficial effects of a housing cooperative sector, we also should not disregard the importance of the rental status of the housing units. By keeping all of the housing units in the permanent ownership of a cooperative, the future market speculations of separate dwellings may be prevented and sustainably regulated through not-for-profit (where rents are based on costs) rent. Only as such, housing cooperatives can be a part of the non-profit housing sector, influence rental housing market regulation and by doing that, providing the possibility for affordable housing alternative with the participatory potential.

References

Adams D, Hess M (2001) Community in public policy: fad or foundation? Aust J Public Adm 60(2):13–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.00205

Arnstein SR (1969) A ladder of citizen participation. J Am Inst Planners 35(4):216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Borowski T (2016) The Founding of More Than Housing. In: Hugentobler M et al (eds) More than housing: cooperative planning—a case study in Zurich. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel

Bourdieu P (1986) The forms of capital, handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. Greenwood Press, Westport

Cabré E, Arnau A (2017) La Borda: a case study on the implementation of cooperative housing in Catalonia. Int J Hous Policy 18(3):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2017.1331591

Coleman JS (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol 94(S1):95–120

Davidson CH, Johnson C, Lizarralde, G et al (2007) Truths and myths about community participation in post-disaster housing projects. Habitat Int 31(1):100–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2006.08.003

Droste C (2015) German co-housing: an opportunity for municipalities to foster socially inclusive urban development? Urban Res Pract 8(1):79–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2015.1011428

Elwood S (2002) Neighborhood revitalization through collaboration: assessing the implications of neoliberal urban policy at the grassroots. GeoJournal 58(2):121–130. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:GEJO.0000010831.73363.e3

Filipovič M (2007) Družbena kohezija in soseska v pozni moderni. Fakulteta za družbene vede, Ljubljana

Forrest K, Kearns A (2001) Social cohesion, social capital and the neighbourhood. Urban studies 38(12):2125–2143. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980120087081

Garcia A (2015) Designing with transitioning communities—the case of la borda. EINA Centre Universitari de Disseny i Art de Barcelona, Barcelona

Garcia M (2006) Citizen practices and Urban government in European cities. Urban Studies 43(4):745–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600597491

Iglič H (2004) Dejavniki nizke stopnje zaupanja v Sloveniji. Družboslovne razprave XX 46–47:149–175

ISSN Internation Co-operative Alliance (2018) Cooperative identity, values & principles. https://www.ica.coop/en. Accessed 1 Sept 2018

Kemeny J, Kersloot J, Thalmann P (2005) Non-profit housing influencing, leading and dominating the unitary rental market: three case studies. Housing Studies 20(6):855–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030500290985

Lang R, Novy A (2014) Cooperative housing and social cohesion: the role of linking social capital. Eur Plan Stud 22(8):1744–1764. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.800025

Lang R, Roessl D (2011) Contextualizing the governance of community co-operatives: evidence from Austria and Germany. Voluntas: international journal of voluntary and nonprofit organizations 22:706

McMaster J (2016) Mehr Als Wohnen. Arcspace. https://arcspace.com/feature/mehr-als-wohnen/. Accessed on 1 Sept 2018

O’Toole K, Burdess N (2004) New community governance in small rural towns: the Australian experience. J Rural Stud 20(4):433–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2004.01.002

Peck J, Tickell A (2007) Conceptualizing neoliberalism, thinking Thatcherism. Contesting Neoliberalism: Urban Front 26:50

Purtik, Zimmerling E, Welpe IM (2016) Cooperatives as catalysts for sustainable neighborhoods—a qualitative analysis of the participatory development process toward a 2000-Watt Society. J Clean Prod 134 A:1–16

Rosol M (2016) Community volunteering and the neo-liberal production of Urban green space. Jovis Verlag GmbH, Berlin, The Participatory City

Schuller T (2001) The complementary roles of human and social capital. J Clean Prod 2(1):18–24

Smith J (2016) Making real plans to transform public housing. Jovis Verlag GmbH, Berlin, The Participatory City

Somerville P (2007) Co-operative identity. J Co-Op Stud 40(1):5–17

Sørvoll J, Bengtsson B (2018) The pyrrhic victory of civil society housing? co-operative housing in Sweden and Norway. Int J Hous Policy 18(1):124–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2016.1162078

Williams J (2006) Designing neighbourhoods for social interaction: the case of cohousing. J Urban Des 10(2):195–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574800500086998

Zimmermann P (2014) Co-building the city with participatory housing in Strasbourg (France). https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=2ahUKEwj0-NnQr_fdAhVE-6QKHciUDOYQFjAAegQICRAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.energy-cities.eu%2Fdb%2FStrasbourg_etude_dialogue_EN.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0z-WdRIAUC5eWWhSKldMLP. Accessed on 1 Sept 2018

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Visković Rojs, D., Hawlina, M., Gračner, B., Ramšak, R. (2020). Review of the Participatory and Community-Based Approach in the Housing Cooperative Sector. In: Nared, J., Bole, D. (eds) Participatory Research and Planning in Practice. The Urban Book Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28014-7_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-28014-7_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-28013-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-28014-7

eBook Packages: Earth and Environmental ScienceEarth and Environmental Science (R0)