Abstract

Birkeland currents that flow in the auroral zones produce perturbation magnetic fields that may be detected using magnetometers onboard low-Earth orbit satellites. The Active Magnetosphere and Planetary Electrodynamics Response Experiment (AMPERE) uses magnetic field data from the attitude control system of each Iridium satellite. These data are processed to obtain the location, intensity and dynamics of the Birkeland currents. The methodology is based on an orthogonal basis function expansion and associated data fitting. The theory of magnetic fields and currents on spherical shells provides the mathematical basis for generating the AMPERE science data products. The application of spherical cap harmonic basis and elementary current system methods to the Iridium data are discussed and the procedures for generating the AMPERE science data products are described.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

7.1 Introduction

The electric dynamo comprising the solar wind kinetic energy interacting with Earth’s magnetic field in space drives a global electric circuit that couples the magnetosphere with the polar ionospheres through the Birkeland currents. The first averaged spatial configuration and intensity of the region 1 and region 2 Birkeland currents were obtained from the low-Earth orbit Triad satellite around 50 years ago (Iijima and Potemra 1976). Using spatially sparse satellite observations from Triad, MAGSAT, Viking and DMSP, the intensity and location dependence of the currents on the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF) was recognised (Bythrow et al. 1982; Iijima et al. 1984; Zanetti et al. 1984; Erlandson et al. 1988). Birkeland currents are typically located between 65\(^\circ \)–75\(^\circ \) magnetic latitude, expanding to 45\(^\circ \) during geomagnetic storms and contracting poleward of 75\(^\circ \) during quiet periods with similar excursions for the southern hemisphere. Subsequent statistical and event studies using Iridium satellite data have confirmed the IMF dependence (Anderson et al. 2008; Green et al. 2009; Korth et al. 2010), provided estimates of ionosphere conductance (Green et al. 2007) and energy transfer via the Birkeland currents (Waters et al. 2004; Korth et al. 2008) and revealed the spatial sequence from small to enhanced current flow (Anderson et al. 2014, 2018). These results derived from Iridium satellite data have highlighted limitations of previous, spatially sparse, in situ measurements, which required months of data when using single satellite studies in order to cover all magnetic local times.

The Iridium satellite constellation is a network of about 90 polar orbiting satellites at an altitude of 780 km. Each satellite contains a 3-axis, vector fluxgate magnetometer as part of the attitude control system. The number of satellites and the spatial coverage make the Iridium constellation an excellent sensor system for space physics research. The quantification and validation of the Iridium magnetometer data for studying the Birkeland currents was discussed by Waters et al. (2001) Anderson et al. (2000, 2002, 2008), Green et al. (2009). After removing magnetic field variations longer than 26 min with suitable filtering, the Iridium magnetometer data are processed to give the perturbation magnetic field, \(\mathbf b =(b_r,b_{\theta },b_{\phi })\) which are dominated by signatures of the Birkeland currents.

Magnetic field data from the Iridium satellites were first available for space physics research in 1999. These were limited to the cross satellite track components of the perturbation magnetic field. Data were obtained from each satellite at a sample period of 200 s. This provided a large improvement in spatial and temporal studies of the Birkeland currents over previous single satellite measurements. While several months of single satellite data are required to build a global pattern (e.g. Gary et al. 1995; Kosch and Nielsen 1995), the Iridium data allowed the required time frame to be drastically reduced to data averaged over \(\approx \) 1h. These 200 s sampled, cross-track only data will be referred to as pre-AMPERE data.

During 2009, enhancements to the Iridium data delivery and processing were introduced under the Active Magnetosphere and Planetary Electrodynamics Response Experiment (AMPERE) project as summarised in Anderson et al. (2014). The data sample period was reduced tenfold from 200 s to a standard 20 s interval from each satellite. Furthermore, a 2 s data sample mode is available for storm case study intervals, enabling higher time resolution studies of active space weather processes. AMPERE data products are available from October 2009 at the web address, http://ampere.jhuapl.edu.

The procedure for estimating the radial current from the pre-AMPERE data was described by Waters et al. (2001). The Iridium, cross-track component data were expanded using spherical cap harmonic basis functions where the expansion coefficients were estimated from a minimum least squared error process. There are two main features of the AMPERE data that required enhancements to the pre-AMPERE data processing described by Waters et al. (2001) and Green et al. (2006). The full vector magnetic field values are available under AMPERE and the higher time cadence provides the ability to resolve smaller spatial structures in latitude. This required high order spherical cap harmonic analyses. In particular, the ability to compute the spatial gradient of the spherical cap harmonic functions for orders greater than 50 over typical spherical cap sizes of \(\theta _0=50^{\circ }\).

In this chapter, the theory and data processing used to obtain the AMPERE science data products available from http://ampere.jhuapl.edu are described. We begin in Sect. 7.2 with a relevant summary of the theory of magnetic fields and currents on spherical surfaces, drawing mostly from the work by Backus (1986). This provides the mathematical framework for computing the Birkeland currents from the Iridium satellite data. Spherical harmonic functions are discussed in Sect. 7.3, followed by a description of the expansion of the Iridium data using vector spherical harmonics as orthogonal basis functions in Sect. 7.4. This leads to a discussion of the vector spherical cap harmonics used for confining the data fit over a cap rather than the full sphere at high order for degree-scale spatial resolution.

The underlying theory and application to Iridium data are illustrated in Sect. 7.5 using examples of the preprocessed input magnetic perturbations data \((b_r,b_{\theta },b_{\phi })\), the estimated perturbation magnetic field data \((b_{r,f},b_{\theta ,f},b_{\phi ,f})\), expanded from the vector spherical cap harmonic basis functions and the derived radial current densities. Properties of the uncertainties in the input and fitted satellite data are discussed in Sect. 7.6 including error statistics and uncertainty estimates in the radial current data product. The spatial resolution of the data is discussed, particularly around the data-dense Iridium satellite track convergence locations in each pole. An alternative to using spherical harmonics is the Spherical Elementary Current System (SECS) basis functions (Amm 1997 and Chap. 2 of this volume). The AMPERE data processed using this approach are discussed in Sect. 7.7. Finally, an example of AMPERE data products combined with other space physics data sets (e.g. SuperDARN radars) is given in Sect. 7.8.

7.2 Magnetic Fields and Currents on Spherical Surfaces

Electric currents have well-defined magnetic fields as specified through the Maxwell equations. The mathematical relationships between magnetic fields and currents on spherical shells were reviewed by Backus (1986). There are three representations that are relevant for magnetic fields in space physics. These are the Gauss, Mie and Helmholtz descriptions. The relevant descriptions, parameters and relationships are summarised in Fig. 7.1. The Gauss form is used for modelling the surface geomagnetic field, where both \(\nabla \bullet \mathbf B \) and \(\nabla \times \mathbf B \) are zero. Approximating the ionosphere as a thin current sheet with anisotropic conductance requires the Helmholtz description. The Mie expressions are used to derive the radial current density, given the input perturbation magnetic field data, \(\mathbf b \), from the Iridium satellites.

Magnetic fields and currents and relevant mathematics below, within and above the ionosphere. The surface curl operator \(\varLambda _1 = \mathbf r \times \nabla \) (Green et al. 2006)

Consider a spherical shell denoted S(a, b), with origin at the Earth centre and with inner radius, a and outer radius b at the minimum and maximum satellite altitudes (\(a<b\)). Since \(\nabla \bullet \mathbf B \) = 0 the vector field, \(\mathbf B \), is solenoidal. The converse is not necessarily true (Backus et al. 1996). A vector field, Q is toroidal in the shell if there is a scalar field, Q, such that

This is the Helmholtz representation of the field, Q in the surface S(a, b). The toroidal scalar, Q, is uniquely determined from Eq. (7.1) provided that for each r in \(a<r<b\), the average is zero, i.e. \({\left\langle Q \right\rangle }_r = 0\).

A vector field, P, is poloidal in the shell if there is a scalar field, P, such that

If the current density \(\mathbf J \ne 0\) in the shell then the Mie representation of the magnetic field, B, is

Equation (7.1) was introduced by Lamb (1881). The Gauss representation used in geomagnetism for main field modelling has \(\mathbf Q = 0\) and \(\nabla ^2 \mathbf P =0\). The vector fields, P and Q, are uniquely determined by the field B in the shell. However, the scalar fields, P and Q are determined by B only to additive functions of r as discussed by Backus (1986). They can be made unique by the constraint that the average values, \({\left\langle Q \right\rangle }_r={\left\langle P \right\rangle }_r=0\).

From Maxwell, with negligible displacement current, the magnetic field, B and the current density, J are related by

Taking the curl of Eq. (7.3) and since J is solenoidal [i.e. \(\nabla \bullet \mathbf J =0]\) the Mie representation of J is

where p and q are the poloidal and toroidal scalars for the current density vector field, J. It follows that these are related to the scalars P and Q describing the magnetic field by

Therefore, a toroidal current produces a poloidal magnetic field while a poloidal current gives a toroidal magnetic field. In summary, toroidal fields are solenoidal fields with zero radial component while poloidal fields are solenoidal fields whose curl has no radial component.

We only have information about the horizontal gradients of the magnetic field from the Iridium data. The perturbation magnetic field, \(\mathbf b \) and current density, \(\mathbf J \) are solenoidal fields but the horizontal components, \(\mathbf b _{\perp }\) and \(\mathbf J _{\perp }\) are not. Therefore, the Mie representation cannot be used directly. However, the Helmholtz representation allows the construction of any vector field from curl-free and divergence-free components. The relationships between the Helmholtz and Mie representations for magnetic fields and currents is described by Backus (1986).

The field aligned (radial) currents (\(J_{\Vert }\)) are derived from the transverse magnetic field perturbations, \(\mathbf b _{\perp } = \mathbf b (\theta ,\phi )\), where \(\theta \) is the co-latitude and \(\phi \) is the longitude coordinate. If \(\mathbf v _{s}\) is some tangent vector field on the spherical surface, S(b), then there is a unique poloidal field

and a unique toroidal field

where \({\nabla }_1\) is the dimensionless surface gradient defined by

The scalar functions, g and h, are determined by \(\mathbf v \) if \({\left\langle g \right\rangle }_b = {\left\langle h \right\rangle }_b=0\) according to

for

and

where \(\mathbf r ^u\) is the radial unit vector so \(\mathbf r ^u f\) is the radial part of v.

The derivations for the divergence and curl of the vector field, \(\mathbf v \), are given in Backus (1986). The results are

and

where

From (7.14), (7.17) and (7.3) any solenoidal vector field, b, can be written

and a similar expression can be written for the current density, \(\mathbf J \)

For radial, field aligned current with no horizontal currents in S(a, c), the magnetic perturbations detected by the Iridium constellation form a toroidal magnetic field. From (7.7) and (7.21) the relation used to obtain the radial current density is

7.3 Spherical Harmonic Basis Functions

The spherical harmonic functions were used by Gauss in 1838 to obtain analytic expressions for the Earth’s magnetic field. This is now a core technique in geophysics and the spherical harmonic expansion of Earth’s main field is publicised as the International Geomagnetic Reference Field (IGRF) as a set of spherical harmonic coefficients. There is an abundance of literature describing geomagnetic field modelling. An excellent resource is the two volumes by Chapman and Bartels (1940) in addition to any text on mathematical methods (e.g. McQuarrie 2003).

The techniques are very similar for modelling perturbation fields due to the Birkeland currents. This section gives a brief summary of these spherical harmonic methods, providing a foundation for describing a spherical cap harmonic expansion of the Iridium data.

The spherical harmonic functions are solutions to the Laplace equation expressed in spherical coordinates. Electric currents internal to the Earth determine the main geomagnetic field, \(\mathbf B _0\), observed on Earth’s surface where \(\nabla \bullet \mathbf B _0 = \nabla \times \mathbf B _0 = 0\). This gives the classic Gauss representation

which is the Laplace equation for some potential function, \(\psi \). In spherical coordinates Eq. (7.23) becomes

The solutions to Eq. (7.24) are usually obtained using the separation of variables technique. At constant radial height (\(R_{sat} = 780\) km) we are interested in the solutions, Y(\(\theta ,\phi \)). The solution in the co-latitude variable, \(\theta \) involves the associated Legendre differential equation

where \(\lambda \) is a constant, \(x=cos\theta \) and \(m=0,\pm 1, \pm 2\),....

For \(m=0\) and \(0\le \theta \le \pi \), the solutions to Eq. (7.25) are the Legendre polynomials, \(P_n(x)\) which may be generated from Rodrigues’ formula

for \(n=0,1,2\),.... For example, the Legendre polynomials are \(P_0(x)=1\), \(P_1(x)=x\), \(P_2(x)=\frac{1}{2}(3x^2-1)\) and so on, with \(-1 \le P_n(x) \le 1\) and all \(P_n(1)=1\). They satisfy the orthogonality relation

For \(m \ne 0\) we have the \(associated\,Legendre\,functions \)

which satisfy

for the Kronecker delta function, \(\delta _{l,n}\) and \(|m| \le l\). The factorial multiplier in Eq. (7.29) shows that these functions have a large range in magnitude even for small increments in m. Since these will be used to construct a basis set of the experimental data, we would like the coefficients to represent the strength of each basis function in the data. One early choice was to use normalised \(P_{l,m}\). However, the standard adopted by the geophysics community in 1939 is Schmidt semi-normalisation where

Including the dependence with longitude gives the spherical harmonics

and their mean squared value over the spherical surface is

The \(e^{im \phi }\) in Eq. (7.32) is implemented by using \(P_l^m cos(m\phi )\) for \(m>0\) and \(P_l^m sin(m\phi )\) for \(m<0\). The eigenvalues, \(\lambda \) in (7.25) are related to l in Eq. (7.32) by \(\lambda =l(l+1)\) so that

This simplifies the computation of \(J_r\) in Eq. (7.22). For \(0\le \theta \le \pi \) the eigenvalues are integers. This is no longer true for spherical cap harmonics.

7.4 Basis Functions and Data Fitting

The Iridium satellites orbit at 780 km above Earth’s surface. At this altitude the magnetic field perturbations detected at high latitudes are assumed to be due to radial currents. Therefore, the perturbation magnetic field is toroidal as defined by Eq. (7.1) and the radial current may be determined using Eq. (7.22). The toroidal scalar, Q, in Eq. (7.1) may be expanded on a basis set of spherical harmonics (Backus 1986)

so that Eq. (7.34) can be used for the second order derivative in Eq. (7.22).

The preprocessing of the magnetic field data from the Iridium satellites for AMPERE provides vector perturbation magnetic field data, \(\mathbf b =(b_r,b_{\theta },b_{\phi })\). These are expanded on a basis set of vector spherical harmonics

which involves the gradient of the scalar spherical harmonics of Eq. (7.32). The derivative of \(Y_l^m\) with respect to \(\phi \) is straightforward, involving a multiplication by m. For \(0\le \theta \le \pi \) and Schmidt semi-normalisation, the derivative of \(P_l^m\) with respect to \(\theta \) is Chapman and Bartels (1940)

and for \(m=0\),

The Iridium constellation provides magnetic field data in six longitudinally spaced orbit planes which gives a maximum value, m=6. However, the latitude spatial resolution changes with the data sample rate and values for \(l>60\) are common for the 20 second sampled data. According to Eqs. (7.36)–(7.38) the gradient of the basis functions at each \((\theta ,\phi )\) of the recorded magnetic field data is required. Therefore, basis functions and the data fit are calculated in an orthogonal coordinate system related to geographic coordinates. The design matrix is a two dimensional array (matrix) containing the basis function values at the locations of the perturbation magnetic field data. If the number of basis functions is nBF and the number of data points is NP then the design matrix for scalar data would be of size nBF by NP. For AMPERE, each vector component of the perturbation magnetic field is loaded into a column vector and the system is solved for the set of coefficients that minimises the squared difference between the data and the estimated values. Since \(\textit{NP}>\textit{nBF}\), Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) may be used to solve for the coefficients (Press et al. 1986).

7.5 Practical Considerations

There are a number of reasons for using Spherical Cap Harmonic Analysis (SCHA) to generate AMPERE data products. The region of interest containing the major current systems is generally located within \(40^{\circ }\) of the poles. Second, AMPERE can provide up to 2 s sampled data resulting in higher spatial resolution which requires a high order fit. For a full sphere spherical harmonic fit, the number of coefficients required to achieve the spatial resolution can become larger than the number of input data points. Third, a basis function fit that employs sine/cosine functions in longitude requires selection of m that satisfies the Nyquist criterion for the largest separation in longitude. Finally, given that the northern and southern hemisphere Iridium satellite track intersection locations are not \(180^\circ \) apart, they may be treated separately by using a spherical cap approach.

The calculation of spherical cap harmonics was described by Haines (1988) and de Santis et al. (1999). The computer program provided by Haines (1988) used a recursion process based on the hypergeometric functions to compute the spherical harmonics over a cap. However, for AMPERE data products these functions need to be evaluated to high order where the recursion relations require the computation of very large numbers, stretching the numerical precision capabilities of computers. In order to circumvent this problem, (Green et al. 2006) used software techniques to increase the computer numerical precision in order to compute these functions. A simpler method is to numerically solve Eq. (7.25) using a finite difference algorithm as an eigen problem, given the two boundary conditions discussed by Haines (1985). In principle, this method allows for the computation of the set of spherical harmonic basis functions over a spherical annulus as used, for example, by Waters and Sciffer (2008).

While the spherical cap harmonic functions may be obtained for any cap size, \(\theta _0\), the computation time is decreased if recursion and identity relationships that are well known for the full sphere associated Legendre polynomials and their derivatives are used, (e.g. Eqs. 7.39 and 7.40). The Iridium data covers all latitudes in six orbit planes at 780 km altitude. Therefore, the combined advantages of efficient computation of basis functions and the use of spherical cap harmonics is obtained by selecting \(\theta _0=90^\circ \). This strategy yields the two basis function sets obtained using the Dirichlet and Neumann boundary conditions from standard math library associated Legendre polynomial routines.

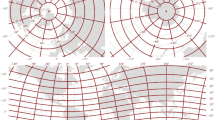

The spherical cap harmonic expansion yields the fitted perturbation magnetic field \((b_{r,f},b_{\theta ,f},b_{\phi ,f})\) and Birkeland current configuration over both the northern and southern hemisphere auroral regions. As an example, the 20 s \((b_{\theta },b_{\phi })\) data for 1520–1530 UT, 24 Aug 2010 are shown in Fig. 7.2a. The data are shown in the Altitude Adjusted Corrected GeoMagnetic (AACGM) latitude (Baker and Wing 1989) and Magnetic Local Time (MLT) coordinate system with 12 MLT at the top. The vector spherical cap harmonic fit magnetic field data are shown in Fig. 7.2b.

Using Eqs. (7.37)–(7.40) for the basis set, followed by Eqs. (7.22) and (7.35), the radial current is obtained and shown in Fig. 7.2c. The region 1 current system is located near \(70^\circ \) with region 2 located a few degrees poleward of \(60^\circ \) AACGM latitude. The Interplanetary Magnetic Field (IMF) magnitude and orientation modulate the Birkeland current pattern (Green et al. 2009). The time shifted solar wind data from the Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) spacecraft for this interval shows the IMF was relatively steady with \((B_x,B_y,B_z) = (7, -16, -8)\) nT. The negative \(B_y\) of the IMF twists the current pattern pushing current poleward on the dayside.

(top) The perturbation magnetic field data from Iridium for 0520–0530 UT, 24 August 2010, (centre) the fitted magnetic field and (bottom) the radial current density for northern (left) and southern (right) hemispheres plotted in AACGM and MLT coordinates (see text). Red identifies outward and blue the inward current

The southern hemisphere data are represented as looking through the Earth from above the north pole. The Iridium tracks in Fig. 7.2a show the larger offset of the spacecraft intersection location from the AACGM pole in the southern compared with the northern hemisphere. This largely contributed to the difficulty in achieving data fits for the southern hemisphere using the pre-AMPERE, cross-track only Iridium data.

The availability of both \(b_{\theta }\) and \(b_{\phi }\) data from Iridium post-2009 allows improved estimates, particularly for the southern hemisphere. As an example, consider the southern hemisphere data for 2348–2358 UT, 4 April 2010 and the straightforward application of a spherical cap harmonic fit as shown in Fig. 7.3. While the fitted magnetic fields look reasonable, the field aligned current pattern shows ‘stripes’ of current segments, particularly on the dawn side over \(70^0-80^\circ \) latitude. This is an effect caused by the mostly longitudinally oriented currents ‘slicing’ across the finite basis function sum, particularly in longitude where \(m \le 6\) in Eq. (7.35) in order to avoid aliasing.

The ‘pole’ (or zero co-latitude) location for the basis functions can be placed anywhere on the sphere (with radius of \(R_E\) + 780 km altitude). In order to maximise longitudinal resolution, zero co-latitude for the data fit is located at the average Iridium track intersection point, which for this case is near \(70^\circ \) and 21 MLT. Given the Iridium satellite altitude of 780 km and the spacing in each orbit plane, it takes about 9 min for full latitude data coverage. Therefore, each fit involves a data collection window of 10 min. For a given 10 min data interval, the average of the satellite track intersections is obtained from the 15 track pair combinations. There are two average intersection locations, one for each hemisphere. For a given hemisphere of data, the ‘shifted pole’ and the input magnetic perturbation data in (orthogonal) geographic (GEO) coordinates are used for the spherical cap harmonic fit.

An outline of the algorithm to improve the fit is as follows. For a given 10 min interval, the data are separated into northern and southern hemisphere caps. The magnetic field perturbation values midway between the Iridium satellite tracks are estimated and folded into the fit with reduced weighting. The simplest estimation scheme is a linear fit (averaged values) between adjacent Iridium tracks. A more advanced approach is to use Spherical Elementary Currents, as described below. Either way, a set of ‘ghost’ data tracks are generated between the Iridium satellite tracks, allowing larger values for m in the fit. The input Iridium data are treated as more important than the ‘ghost’ data in the weightings for the data fit. The \(l=50\), \(m=8\) spherical cap harmonic fit to the data in Fig. 7.3 is shown in Fig. 7.4.

7.6 Estimating Uncertainties

Magnetometer data obtained from the Iridium satellite constellation have been used to estimate the field aligned current (Waters et al. 2001; Anderson et al. 2002; Green et al. 2009), high latitude Poynting flux (Waters et al. 2004; Korth et al. 2008) and ionosphere conductance (Green et al. 2007). Since these are key quantities in magnetosphere–ionosphere coupling it is important to estimate the magnitudes and identify sources of uncertainties in the AMPERE data products. In this section, the uncertainties in the magnetic field and the derived current are discussed.

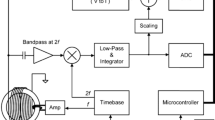

Uncertainties in the measured magnetic field values involves the magnetometer specifications and performance on each Iridium satellite and the associated analog to digital data conversion. The instruments are a fluxgate design which sense the total magnetic field in three orthogonal component directions. These data are reduced to \((b_r,b_{\theta },b_{\phi })\) by subtraction from a main field model, filtering and adjustments for orthogonality and channel cross-talk as described by Anderson et al. (2000). This process also provides the data quality values which are used as the measurement errors, \(\sigma _i\).

The perturbation magnetic field data are fit to a set of orthogonal functions with the coefficients determined by minimising the least squared error. The merit function is (Press et al. 1986)

where \(Q_i(r,\theta ,\phi )\) are the estimated values obtained from the fit coefficients \(a_{l,m}\) via Eq. (7.35) and \(b_i(r,\theta ,\phi )\) are the experimental data. This is a common data fitting method and discussions of the ‘goodness of fit’ may be found in many statistical analysis texts such as Johnson and Wichern (2002) and Press et al. (1986). If measurement errors are normally distributed, then the merit function in Eq. (7.41) follows a chi-squared distribution and the least squared and maximum likelihood estimates are equivalent.

The input \((b_r,b_{\theta },b_{\phi })\) values are located at coordinates \((r,\theta ,\phi )\) where the coefficients and basis functions provide the fitted perturbation magnetic field estimates, \((b_{r,f},b_{\theta ,f},b_{\phi ,f})\). For a data sample interval of 20 s, the number of magnetic field values from Iridium for a 10 min interval is \(\approx \)2000. The residuals are the differences between the input and fitted values and these are included in the AMPERE data products. For estimating the radial current density, we focus on the \((b_{\theta },b_{\phi })\) data. The input versus the fitted data for 0520–0530 UT, 24 August, 2010 are shown in the two upper panels of Fig. 7.5. A ‘good’ fit to the data is shown by points close to the line with unity slope. In order to check for anomalies in the residuals and the variance, the residuals are plotted versus the predicted values in the lower panels of Fig. 7.5. There is no clear trend, indicating the basis function model adequately describes most of the data and the variance is independent of the input data.

The minimisation of the merit function also yields a covariance matrix which is related to the data uncertainties if the residuals have a normal distribution. Figure 7.6 shows the residuals as a function of the normal distribution quartile (Q-Q plots) [e.g. see Johnson and Wichern (2002)] for the fitted (\(b_{\theta },b_{\phi }\)) data. A straight line indicates the data are from a normal distribution. This is approximately true for the \(b_{\theta }\) component and out to one and a half standard deviations from the mean for the \(b_{\phi }\) component. A measure of the ‘straightness’ of the line in the Q-Q plot is the correlation coefficient, which for these data are \(r_{Q,\theta }\) = 0.97 and \(r_{Q,\phi }\) = 0.88. A test, at some significance level, for rejecting the hypothesis that the residuals are from a normal distribution may be formulated using these values of \(r_Q\). The change in slope in the tails of the \(b_{\phi }\) component is the reason for the smaller \(r_{Q,\phi }\) and this corresponds to the larger values of \(b_{\phi }\) which are often confined to a few degrees in latitude and would be better estimated using a higher order fit.

Normal distribution quartiles versus residuals for the Iridium data and spherical harmonic fit of the data in Fig. 7.2

Given estimates of the uncertainties in \((b_{\theta },b_{\phi })\), the associated uncertainties in the radial current may be determined. The procedure for taking the perturbation magnetic field values obtained from Iridium to estimate the radial current density involves the derivatives of potential functions according to Eq. (7.22). An uncertainty estimate may be obtained by assuming a sheet current structure that flows radially and extends along the \(\phi \) coordinate. Integration of Ampere’s law (Eq. 7.4) gives \(b=\mu _0 K/2\) where K is the current density in \(Am^{-1}\). The field aligned current density, J (\(Am^{-2}\)) is obtained through division by the current sheet width. Therefore, the proportional error in J is the sum of the proportional errors in the perturbation magnetic field and the resolution in latitude (\(\theta \)).

An estimate for the uncertainty in the radial current may also be obtained using the statistics of the perturbation magnetic field values. The radial component of Eq. (7.4) is

Therefore, \(J_r=j_{r,1}+j_{r,2}+j_{r,3}\) where

The measurement resolution in the \(\theta \) coordinate is related to the spherical harmonic fit order, l (or \(n_k\) for cap harmonics). The highest order, associated Legendre function has a minimum wavelength, \(\lambda _{min}\) so the uncertainty in \(\theta \) is \(\delta \theta = \lambda _{min}/2\). Similarly, the separation of the Iridium orbit planes gives the resolution in \(\phi \) as \(\delta \phi =\pi /6\). The uncertainties in \(b_{\theta }\) and \(b_{\phi }\) are \(\delta b_{\theta }\) and \(\delta b_{\phi }\) and may be estimated from the statistics of the residuals. From Eqs. (7.43)–(7.45), the uncertainties in the field aligned current density are

with the total uncertainty in the field aligned current, \(\delta J = \sqrt{\delta j_{r,1}^2 + \delta j_{r,2}^2 + \delta j_{r,3}^2}\). The mass production of data products for AMPERE involves a fixed set of analysis and fit parameters. Users of these data products should communicate with the AMPERE science data team for advice on the quality and uncertainties in the data for specific intervals.

7.7 Spherical Elementary Currents and Iridium Data

The orbit configuration of the Iridium satellites provides data at varying spatial separations in longitude. The spatial density of data samples is greater around the Iridium satellite track intersection locations providing increased spatial resolution of the currents where the satellite tracks are close. The average location of pairs of Iridium track intersections moves relative to geomagnetic coordinates and the currents form different spatial patterns depending on the IMF and magnetic activity. Therefore, an average Iridium track intersection location in a given hemisphere might occur between the main current systems. This represents a difficult situation for data fitting using a finite number of SCHA basis functions. One alternative approach to SCHA is the Spherical Elementary Currents Systems (SECS).

The SECS basis functions were described by Amm (1997, 2001). This approach has many similarities with the multiple multipole method used for solving the Maxwell equations (e.g. Ballisti and Hafner 1983). The SECS basis functions have been applied to both ground and satellite magnetometer data. For the latter, with data confined along single satellite tracks, a one-dimensional (1D) version of the method has been developed (Vanhamaki et al. 2003; Juusola et al. 2006). In this section, application of the 2D, curl-free SECS basis functions to Iridium data is described. These are used for the AMPERE regional fit data products with the aim of providing enhanced spatial resolution around the Iridium satellite track intersection regions.

As discussed in Chap. 2 (this volume), the SECS expansion of spatial data are based on a divergence-free and a curl-free basis set to give the total field. They relate the field aligned and (horizontal) ionospheric currents with the perturbation magnetic fields. The curl-free current basis is

where the dashed coordinates reference the local SECS coordinate system with the pole at \(\theta '=0\), R is the radius of the sphere on which the poles are placed and \(\mathbf e _{\theta '}\) is the unit vector. The magnetic field from the curl-free current basis is

for r > R and zero for r < R . It is straightforward to show that

There are a number of parameters to adjust in the SECS approach to data fitting. The main considerations are the number and location of the poles and solution grid points. For dense spatial grids compared to the experimental data locations and over limited spatial extent, the modelled magnetic field and currents appear reasonable as illustrated in examples provided by Amm (1997) and Amm and Viljanen (1999). Constraints on the number of pole and solution locations include computation time required to solve the matrix equation for the fit coefficients and the spatial information afforded by the input experimental data. Depending on the number of poles and the spatial separation between the input data and the pole locations, the current pattern can become less smooth with the appearance of patches of localised current.

A direct application of the SECS basis to Iridium magnetic field perturbation data proved unsatisfactory for a number of reasons that are related to the spatial properties of the basis functions and the Iridium data. Equations (7.49) and (7.50) show an infinity at \(\theta '=0\). This was eliminated by changing the cotangent function to a tangent function within a ‘limit angle’ that spans a SECS grid cell (Vanhamaki et al. 2003). The modified basis function is shown in Fig. 7.7 with the limit angle shown by a dashed line. The horizontal axis scale is \(R \theta '\) where R is 6370 + 780 km, the radius of the Iridium constellation.

Equation (7.49) and Fig. 7.7 show that there is no flexibility for the spatial extent of the basis function. However, the Iridium data have finer spatial resolution around the satellite track intersection locations compared with data at lower latitudes. In practice, this results in a mismatch between the spatial properties of the basis function and the data. In fact, locating the SEC poles midway between the satellite tracks gave very small root mean squared error values between the input magnetic field and fitted values. However, the currents became very localised and did not span the space between the satellite tracks. This is an illustration of the care required when interpreting fitted data using a root mean squared error metric.

In order to design a more robust metric for fitting the 2D data from Iridium, a region 1 and 2 model current system was constructed. The magnetic perturbations from this model current system were calculated using both a Biot–Savart integration and a high order spherical cap harmonic expansion. This provided model radial current and horizontal magnetic field values with an improved data fit metric based on the root mean squared values for both magnetic field and current. Using these model data, a number of spatial data fit methods and their variations were assessed.

The spatial information needs to be more flexible for the 2D SECS method applied to Iridium data. One approach was to extend the design matrix by including a constraint on the longitudinal derivative of the combined basis function solution. While this modification smoothed the resulting radial current, it required an estimate of a ‘reasonable’ derivative to be applied a-priori, and the current magnitudes were reduced compared with the input values.

Another approach was to consider a different basis function formulation with spatial extent flexibility. For the curl-free magnetic field and radial currents in AMPERE, the source current is assumed to be radial but the horizontal spatial variation may be different to a cotangent function. In principle, a Biot–Savart integration may be coded in order to obtain the magnetic field from any current distribution. However, analytic expressions have advantages for computational speed. A Gaussian basis function was trialed, with different widths used to adjust the spatial extent. A disadvantage with this approach was found to be related to the symmetric nature of the basis function, while the input Iridium data have less data in longitude compared with latitude.

Before describing the approach chosen, a comment or two on the spatial grids are in order. The SECS algorithm involves three coordinate systems. For AMPERE these are the input data in GEO, the number and location of the SECS basis function poles and the grid on which the solution is desired. The input data locations are determined by the Iridium satellite locations. The SECS pole and solution spatial grids were constrained by being interlaced as described in Chap. 2 (this volume). The desired data product is the radial current, in \(\mu Am^{-2}\), which requires calculation of the fit coefficients, \(I_0\) and horizontal area. Therefore, a quasi-equal area grid was chosen, similar to that used by Ruohoniemi and Baker (1998) for HF radar data. The latitudinal separation is fixed and the longitudinal separation varies with latitude in order to ensure an integer number of grid cells with the same area in each latitudinal ring.

The method chosen for obtaining regional data fits around the Iridium satellite track intersection locations was a combination of the SECS and spherical cap harmonic bases. The input, preprocessed Iridium magnetometer data are used to compute the SCHA solution, (\(b_{\theta ,f},b_{\phi ,f})\) over the quasi-equal area grid. This grid is then searched for locations where the input data are located and the SCHA model values are replaced by the input (\(b_{\theta },b_{\phi })\). The combined input and SCHA data are then used to compute the SECS solution, weighting the SCHA values as less important. The weighting was determined by using the model current and magnetic field data, computing data fits with different weighting in order to minimise the residuals. Once the SECS coefficients are obtained, values for the model magnetic field may be computed on any spatial grid encompassed by the input data. Vanhamaki (2007) recommend that the SECS grid exceed the spatial extent of the solution grid. It is straightforward to also obtain values for the equivalent horizontal current density. The AMPERE regional data method applied to the Iridium data for 0520–0530 UT 24 Aug 2010 is shown in Fig. 7.8.

7.8 AMPERE and Other Data Sets

The temporal and spatial resolution of the AMPERE data provides unique opportunities to investigate details of the electrodynamics of magnetosphere–ionosphere energy exchange and coupling. The previous, cross-track only, Iridium data have been combined with other comprehensive data sets to provide estimates of the input Poynting flux (Waters et al. 2004; Korth et al. 2008) and ionosphere conductivity (Green et al. 2007). In addition to improved temporal resolution, the AMPERE data may yield improved estimates of these parameters through the introduction of the full vector perturbation magnetic field values. The integration of AMPERE data with the electric field measurements obtained from the Super Dual Auroral Radar Network (SuperDARN) is an example.

The SuperDARN is an international consortium that operate 30 high frequency (8–20 MHz) over-the-horizon research radars located primarily to study the auroral and high latitude regions (http://vt.superdarn.org). Using a 16 antenna broadside array, the signal is phased to form a broad vertical but narrow azimuth (\(\approx 3^\circ \)) radiation pattern that is steered over \(52^\circ \) in 16 equi-spaced azimuth directions. A multi-pulse transmit pattern and autocorrelation data processing allow ranges out to \(\approx \) \(3000\) km and Doppler shifts from target velocities up to \(\approx \)1 km/s to be resolved. The dual instrumentation features overlapping radar fields of view in order to resolve the horizontal plasma velocity vectors, v. The electric field vector, E in the ionosphere is then estimated from the geomagnetic field, B using \(\mathbf E =-\mathbf v \times \mathbf B \). The location of the radars limits the magnetic latitude extent of the data to \(\approx 60^\circ \), although expansion of the network to lower latitudes is progressing.

The electric field estimates from the radars are available from both hemispheres over latitudes extending from the poles to a spherical cap size of \(30^\circ \). The AMPERE data provide the perturbation magnetic field estimates at the same locations as the radar data. The combined data are used to calculate the radial component of the Poynting flux, \(\mathbf E \times (b_{\theta ,f},b_{\phi ,f})\), as shown in Fig. 7.9. The latitude extent is limited by the radar data. Comparing with the Birkeland current pattern in Fig. 7.2c shows that the downward Poynting flux is largest at latitudes between the region 1 and 2 current systems. The spatial distribution is often quite different in the northern compared with the southern hemisphere and this is thought to be controlled by details of the ionosphere conductance. The total power is obtained by integrating the radial Poynting flux over the area of the caps. For the 24 August 2010, 0520–0530 UT interval the power estimate is \(\approx \)30 GW for the north and \(\approx \)20 GW for the southern hemisphere. These are most likely underestimates due to factors such as the limited spatial coverage and that the estimated electric and magnetic fields are probably smaller due to the choice of latitude resolution (spherical harmonic fit order) in both data sets as discussed by Korth et al. (2008).

7.9 Conclusion

The AMPERE project provides estimates of the radial current and the full vector perturbation magnetic field at any location over a sphere with origin at Earth’s centre and radius 780 km above Earth’s surface. The magnetic field may be adjusted for other altitudes by multiplication of the data by a factor that has an \(r^{3/2}\) dependence. For AMPERE, the magnetometer data from the Iridium satellites are sampled at 20 s intervals, a factor of 10 increase over previous data obtained from this constellation. For storm time case study intervals, the sample interval may be reduced to 2 s. This improves the spatial resolution in latitude, requiring a high order in the spherical harmonic fitting process. The time interval required to obtained full latitude coverage is several minutes which corresponds with the time taken for each Iridium satellite to move (in their orbit plane) the distance equal to their latitude spacing. These two factors determine the minimum number of data points required to calculate the spherical harmonic expansion coefficients. The full vector perturbation magnetic field and the field aligned current are then estimated over a suitable spatial grid and made available to the scientific community.

Alternative basis functions, such as the SECS, may also be used. While the spherical cap harmonics have a more global reach due to the domain of the basis functions, the SECS basis is more localised and may be used for regional data fits. AMPERE data products are available for download from http://ampere.jhuapl.edu. Although every effort is made to provide the highest quality, as with all experimental data, the Iridium data are not perfect. There are a number of parameters that are involved in the data processing, starting from receipt of the data from Iridium Communications through to the final AMPERE data products. Through experience, various parameters have been chosen for bulk data processing and web display. The AMPERE web site provides researchers with sufficient information to identify intervals of interest. As specified on the AMPERE web site, in order to ensure high quality and the use of optimum parameters for the processed data, any publication of AMPERE data products should involve consultation with the AMPERE science team.

References

Amm, O. 1997. Ionospheric elementary current systems in spherical coordinates and their application. Journal of Geomagnetism and Geoelectricity 49: 947–955.

Amm, O. 2001. The elementary current method for calculating ionospheric current systems from multisatellite and ground data. Journal of Geophysical Research 106: 24,843–24,855.

Amm, O., and A. Viljanen. 1999. Ionospheric disturbance magnetic field continuation from the ground to the ionosphere using spherical elementary current systems. Earth Planet Space 51: 431–440.

Anderson, B.J., K. Takahashi, and B.A. Toth. 2000. Sensing global Birkeland currents with Iridium engineering magnetometer data. Geophysical Research Letters 27: 4045–4048.

Anderson, B.J., K. Takahashi , T. Kamei, C.L. Waters, and B.A. Toth. 2002. Birkeland current system key parameters derived from Iridium observations: Method and initial validation results. Journal of Geophysical Research 107 (A6). https://doi.org/10.1029/2001JA000080.

Anderson, B.J., H. Korth, C.L. Waters, D.L. Green, and P. Stauning. 2008. Statistical Birkeland current distributions from magnetic field observations by the Iridium constellation. Annales Geophysicae 26: 671–687.

Anderson, B.J., H. Korth, C.L. Waters, D.L. Green, V.G. Merkin, R.J. Barnes, and L.P. Dyrud. 2014. Development of large-scale Birkeland currents determined from the active magnetosphere and planetary electrodynamics experiment. Geophysical Research Letters 41: 3017–3025. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL059941.

Anderson, B.J., Olson H.C.N. Korth, R.J. Barnes, C.L. Waters, and S.K. Vines. 2018. Temporal and spatial development of global Birkeland currents. Journal of Geophysical Research 123: 4785–4808. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA025254.

Backus, G. 1986. Poloidal and toroidal fields in geomagnetic field modeling. Reviews of Geophysics 24: 75–109.

Backus, G., R. Parker, and C. Constable. 1996. Foundations of geomagnetism. Cambridge University Press.

Baker, K., and S. Wing. 1989. A new magnetic coordinate system for conjugate studies at high latitudes. Journal of Geophysical Research 94: 9139–9243.

Ballisti, R., and C. Hafner. 1983. The multiple multipole method in electro- and magnetostatic problems. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 19: 2367–2370. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.1983.1062871.

Bythrow, P., T. Potemra, and R. Hoffman. 1982. Observations of field-aligned currents, particles, and plasma drift in the polar cusps near solstice. Journal of Geophysical Research 87: 5131–5139. https://doi.org/10.1029/JA087iA07p05131.

Chapman, S., and J. Bartels. 1940. Geomagnetism, vol. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

de Santis, A., J.M. Torta, and F.J. Lowes. 1999. Spherical harmonic caps revisited and their relationship to ordinary spherical harmonics. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth 24: 935–941.

Erlandson, R.E., L.J. Zanetti, T.A. Potemra, P.F. Bythrow, and R. Lundin. 1988. IMF B(y) dependence of region 1 Birkeland currents near noon. Journal of Geophysical Research 93: 9804–9814. https://doi.org/10.1029/JA093iA09p09804.

Gary, J.B., R.A. Heelis, and J.P. Thayer. 1995. Summary of field aligned Poynting flux observations from DE 2. Geophysical Research Letters 22: 1861.

Green, D.L., C.L. Waters, B.J. Anderson, H. Korth, and R.J. Barnes. 2006. Comparison of large-scale Birkeland currents determined from Iridium and SuperDARN data. Annales Geophysicae 24: 941–959.

Green, D.L., C.L. Waters, H. Korth, B.J. Anderson, A.J. Ridley, and R.J. Barnes. 2007. Technique: Large-scale ionospheric conductance estimated from combined satellite and ground-based electromagnetic data. Journal of Geophysical Research 112(A05303). https://doi.org/10.1029/2006JA012069.

Green, D.L., C.L. Waters, B.J. Anderson, and H. Korth. 2009. Seasonal and interplanetary magnetic field dependence of the field-aligned currents for both northern and southern hemispheres. Annales Geophysicae 27: 1701–1715.

Haines, G.V. 1985. Spherical cap harmonic analysis. Journal of Geophysical Research 90: 3195–3216.

Haines, G.V. 1988. Computer programs for spherical cap harmonic analysis of potential and general fields. Computers and Geosciences 14: 413–447.

Iijima, T., and T.A. Potemra. 1976. The amplitude distribution of field-aligned currents at northern high latitudes observed by Triad. Journal of Geophysical Research 81: 2165–2174.

Iijima, T., T.A. Potemra, L.J. Zanetti, and P.F. Bythrow. 1984. Large-scale Birkeland currents in the dayside polar region during strongly northward IMF: A new Birkeland current system. Journal of Geophysical Research 89: 7441–7452.

Johnson, R.A., and D.W. Wichern. 2002. Applied multivariate statistical analysis. Prentice-Hall.

Juusola, L., O. Amm, and A. Viljanen. 2006. One-dimensional spherical elementary current systems and their use for determining ionospheric currents from satellite measurements. Earth Planets and Space 58: 667–678.

Korth, H., B.J. Anderson, J.M. Ruohoniemi, H.U. Frey, C.L. Waters, T.J. Immel, and D.L. Green. 2008. Global observations of electromagnetic and particle energy flux for an event during northern winter with southward interplanetary magnetic field. Annales Geophysicae 26: 1415–1430.

Korth, H., B.J. Anderson, and C.L. Waters. 2010. Statistical analysis of the dependence of large-scale Birkeland currents on solar wind parameters. Annales Geophysicae 28: 515–530.

Kosch, M.J., and E. Nielsen. 1995. Coherent radar estimates of average high-latitude ionospheric Joule heating. Journal of Geophysical Research 100:12,201–12,215.

Lamb, H. 1881. On the oscillations of the viscous spheroid. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 13: 51.

McQuarrie, D.A. 2003. Mathematical methods for scientists and engineers. Sausalito, California: University Science Books.

Press, W.H., S.A. Teukolsky, W.T. Vetterling, and B.P. Flannery. 1986. Numerical recipes in Fortran 77: The art of scientific computing, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press.

Ruohoniemi, J.M., and K.B. Baker. 1998. Large scale imaging of high latitude convection with Super Dual Auroral Radar Network HF radar observations. Journal of Geophysical Research 103:20,797–20,811.

Vanhamaki, H. 2007. Theoretical modeling of ionospheric electrodynamics including induction effects. Finnish Meteorological Institute Contributions, electronic version available at http://ethesishelsinkifi/66.

Vanhamaki, H., O. Amm, and A. Viljanen. 2003. One-dimensional upward continuation of the ground magnetic field disturbance using spherical elementary current systems. Earth Planets Space 55: 613–625.

Waters, C.L., M.D. Sciffer. 2008. Field line resonant frequencies and ionospheric conductance: Results from a 2-D MHD model. Journal of Geophysical Research 113(A05219), https://doi.org/10.1029/2007JA012822.

Waters, C.L., B.J. Anderson, and K. Liou. 2001. Estimation of global field aligned currents using the Iridium\(^{ riptsize\textregistered }\) system magnetometer data. Geophysical Research Letters 28 (11): 2165–2168.

Waters, C.L., B.J. Anderson, R.A. Greenwald, R.J. Barnes, and J.M. Ruohoniemi. 2004. High-latitude Poynting flux from combined Iridium and SuperDARN data. Annales Geophysicae 22: 2861–2875.

Zanetti, L.J., T.A. Potemra, T. Iijima, W. Baumjohann, and P.F. Bythrow. 1984. Ionospheric and Birkeland current distributions for northward interplanetary magnetic field: Inferred polar convection. Journal of Geophysical Research 89: 7453–7458. https://doi.org/10.1029/JA089iA09p07453.

Acknowledgements

Support for AMPERE has been provided under NSF sponsorship under grants ATM-0739864 and AGS-1420184. We are greatly indebted to the contribution of Iridium Communications for providing the data for AMPERE. We thank the International Space Science Institute (ISSI) in Bern, Switzerland for supporting the Working Group Multi Satellite Analysis Tools—Ionosphere from which this chapter resulted. The editors thank Ryan Mcgranaghan for his assistance in evaluating this chapter.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Waters, C.L., Anderson, B.J., Green, D.L., Korth, H., Barnes, R.J., Vanhamäki, H. (2020). Science Data Products for AMPERE. In: Dunlop, M., Lühr, H. (eds) Ionospheric Multi-Spacecraft Analysis Tools. ISSI Scientific Report Series, vol 17. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26732-2_7

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-26732-2_7

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-26731-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-26732-2

eBook Packages: Physics and AstronomyPhysics and Astronomy (R0)