Abstract

For organizational reasons, school administrators tend to classify pupils based on the neighborhood they live in. The residential area is therefore an important indicator of the composition of different school classes—at least in the case of Swiss primary schools. Due to this logic, teachers are confronted with the characteristics of the neighborhood in which their schools are situated. Because pupils carry their everyday problems with them, the social situation in the neighborhood is also reflected in the classroom. In areas with a high concentration of social problems, this poses an especially big challenge for teachers. But what do we know about the children’s perspective? How do they see their neighborhood? What do they expect from school? How do they view the relation between neighborhood and school? The author discusses these questions on the basis of findings of a research project about lived spaces in a medium-sized Swiss town.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Appropriation

- Community

- Children’s geographies

- Everyday social geographies

- Neighborhood

- Social geography

- Social space

- Subjective maps

- School

- Topological space

Introduction: Rico, Oskar, and Their Adventures: A Fictional Story

Ten-year-old Rico has ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder). The boy, who describes himself as “deeply gifted,” lives alone with his mother at Dieffenbachstraße 93 in Berlin. She makes sure that Rico’s world is carefully ordered. The routes that he takes to get to school or the shop are always the same. His mother even marks the street crossings for her son with plastic bottles (Steinhöfel, 2008, p. 32). The objects in the apartment all have their designated place (and are, if necessary, labelled with Post-it notes). Even the circle of trusted people in the neighborhood is clearly defined. If Rico loses his orientation and has to think hard, his thoughts begin to jump around in his head like bingo balls. He must therefore keep his thoughts organized all the time. Writing in his diary—in the film he speaks into a recording device—helps him sort out more complicated situations or problems.

In the second children’s adventure book by Andreas Steinhöfel, entitled “Rico, Oskar und das Herzgebreche” [Rico, Oskar and the heartbreak], Rico is riding on a motorcycle outside Berlin with his teacher Mr. Wehmeyer, who wanted to do something nice for him and show him something new. For Rico this situation, so far from his familiar neighborhood, is very unsettling, even frightening. But he does not dare say anything because Mr. Wehmeyer is a teacher and (quote): “You never know with teachers. Maybe they even give you marks for riding a motorcycle” (Steinhöfel, 2013, p. 12Footnote 1). The following conversation takes place as the two, having stopped to rest, gaze out on a corn field:

“Where does this road go?” I (Rico) asked. “To the south,” said Wehmeyer, and then added, probably because he remembered that I’m not so good with directions, “If you look at a globe, ‘south’ is down below. Downwards, so to speak.”

I looked at the road and knew that this was, so to speak, nonsense. Because at some point you wind up at the South Pole. And then you can’t go any further down. All you can go is up, cause there’s no more room for south. But, of course, whoever invented the directions never thought of that, and now it was my problem.

Wehmeyer looked like he didn’t have any problems at all. He smiled and said quietly: “It’s really nice here, isn’t it?”

I nodded. Nice and terrifying. I just wanted to get out of there, I didn’t care in what direction. (Steinhöfel, 2013, p. 13)

This fictional story about the deeply gifted boy Rico contains the question that this article will focus on: How do young people learn to see and understand the world? And how can we describe the appropriation processes that accompany this from a sociogeographic perspective?Footnote 2

A completed research project of the Department of Social Work at the FHS St. Gallen (University of Applied Sciences) links these two sociogeographic questions with the question of how professional social work can be structured in such a way as to support, facilitate, and enhance the potential actions and activities of individuals, groups, and communities. Social work is seen as something that should support appropriation processes and/or facilitate appropriation situations, especially for disadvantaged individuals.

Preliminary Note: Everything Depends on the Viewer’s Perspective

In the passage about Rico, we experience two manners of viewing the world. The teacher Wehmeyer sees the road as a line on a globe running from north to south. The vision of the world upon which this idea is based can be described as follows: From any single clearly identifiable point on the globe, all other points can be defined, but multiple points allow one to create a so-called topological space. This space can be described in terms of absolute distances, that is, meters and kilometers, and rendered on a map projection by means of right-angled coordinates. This sober vision of the world follows the laws of Euclidean geometry and seems to conform with the corporeality and materiality of the world of things. The idea of space as a frame or container for social content corresponds to the absolutistic concept ofspace discussed in various disciplines (e.g., Harvey, 1973, 2005; Löw, 2001), which has its origins in classical physics. In his theory of absolute space, Isaac Newton (1642–1727) described space as a shell (container) with no material properties of its own and inside it (corporeal) objects. The following nuance is, however, important: From a scientific perspective, a point on the globe appears absolute, that is, it can be described in terms of geographic longitude and latitude, independent of the viewer. All points of the compass can be identified in reference to this point. As this bewilders Rico, the teacher Wehmeyer uses a practical approach, introducing the perspective of the subjective viewer. We geographers know (and fear) the terms left, right, up, down, and downwards as they are utilized in everyday language to refer to a subjective sense of the position of other points or locations in relation to one’s own temporary standpoint.

The teacher’s intention is to calm Rico and to offer a practical answer to his question regarding the direction of the road. The protagonist is described as living in an orderly world full of routine in which everything has its proper place. The idea that the road runs further and further downwards to the south, and that the south is located somewhere far below troubles Rico. The bingo balls in his head start jumping around. The writer Steinhöfel uses this metaphor to describe the chaos that ADHD unleashes in the boy’s head. Rico mentally travels to the South Pole and pictures to himself that it is not possible to travel any further southwards. This confuses and unsettles him. Rico’s world view, a practical conception of the world, puts us in an entirely different realm than the sober, scientific perspective embodied by the teacher Wehmeyer. Scientific researchers are faced with the challenge of describing this practical realm and the experienced or (in Rico’s case) imagined reality that goes along with it in a scientifically adequate manner. A way to do this is to render the actions of individuals and the motivations and logics that lie behind these actions comprehensible and to identify the accompanying spatial implications.

In projects that means to initially focus on the everyday reality of very different individuals who come to understand the world through their embedded social situations and individual societal conditions, but also through their unique interpretations and biographical experiences. By acting, these individuals establish their position or location. In this way they bring other objects and bodies together into meaningful constructions. To do so, they not only have to comprehend the meanings of things and the contexts of their actions but must also be able to insert and assert themselves in these contexts. Social geographers are interested in how this process of positioning takes place in relation to social spaces. Or, to put it somewhat more scientifically, they are interested in how space is fabricated or (re)produced by distinct actors in their everyday actions (Kessl & Reutlinger, 2010). The concept of space should be relational in nature: a “result of and means of carrying out action-specific constitutional processes” (Werlen & Reutlinger, 2005, p. 49). This implies that space cannot be systematically defined by means of measurements but only by reconstructing a range of contexts and influences relative to a specific perspective (Reutlinger, 2007).

If one studies the everyday world of different individuals, one cannot help but become conscious of the fact that these worlds do not exist per se, like objects, but are ever being recreated by distinct actors. The term appropriation can be helpful to describe this process, as will be discussed in greater detail.

The Concept of Appropriation and Everyday Social Geographies

Though the term appropriation is used quite differently in various scientific discourses, what is common to all these discourses is that in essence the term describes the manner in which an individual exists in or enters the world as an operative human being (Deinet & Reutlinger, 2004, 2014; Reutlinger, 2012). Despite this common essence, the basic question of the relationship between humans and the world is answered in very distinct manners.

One way of understanding the relationship between humans and the world is as a one-sided process of inscription. In this case, focus always remains on the change in ownership of material or symbolic goods. Yet the dimensions of the process of appropriation and the effects of this process on the world and humans are not considered. According to this view, education is instructional or communicative, with the goal of explaining the world order and enforcing this order by means of instruction should its rules be violated, whereby instruction is above all understood as a one-way communication of societal values. Appropriation as a one-way process of inscription can, however, also be grasped in a different manner, namely as the way in which the world makes itself available to an individual. Here, appropriation has the opposite quality as the one described above: Children and youth enter a world that they have not yet appropriated and gradually embrace and internalize it as they grow older by giving it a new shape in accordance with their own ideas and needs, taking possession of it, and in this way acquiring the ability to act (Hüllemann, Reutlinger, & Deinet, 2017).

In contrast to these conceptions, however, appropriation can also be understood as a “reciprocal communicative process between humans and the world” (Graumann, 1990, p. 125). This point of view places emphasis on the dimensions of the appropriation process, through which an individual becomes part of the world, yet the world also becomes part of the individual. In this way both are changed, though the world is not created anew, as the appropriative act is influenced by what already exists: specific structures, patterns, and rules. Children and young people entering into such specific environmental settings form their own subjectivity as they struggle to comprehend this world, but they also inscribe themselves into the environment through appropriative achievements, exerting an influence on it in this way. In the reciprocal relationship between humans and the world described here, the role of education could be described as follows:

On the one hand, the goal of educational measures is to help and support children and young people engage in this appropriation process by making preexisting objectifications accessible—by means of explanations or common activities. Yet an equal share of educational measures are intended to facilitate independent encounters with preexisting structures and phenomena in order to allow children and young people to create new objectifications. This means that through the facilitation of free spaces, personal interpretations, search processes, and experimentation in general, young people are moved to inscribe themselves into the world. This implies that the appropriation processes of other individuals who react to these objectifications are also taken into account. (Hüllemann et al., 2017)

By studying appropriative acts, researchers can achieve insight into how certain groups of children and young people fabricate spaces and comprehend the world. These processes can be described as everyday social geographies (Reutlinger, 2017; Reutlinger & Brüschweiler, 2016). In the following chapter, I will examine a specific project and define the concept of appropriation more precisely.

DoRe Research Project “School as a Social Space”

In the course of the research project entitled “School as Social Space: Reconstruction of School as a Social Space in the Context of City Neighborhood Development, With Special Focus on two Neighborhoods of a Small Swiss City,” researchers examine the relationship between school and neighborhood from a child’s perspective (Fritsche et al., 2011). DoRe, an abbreviation for “do research,” was a funding program of the Swiss National Science Foundation that ended in 2014. It focused on the specific framework conditions of Swiss universities and their financing logic. The project background was the evaluation of local social work services carried out by the Institute of Social Work of the FHS St. Gallen for the city’s Department of Social Affairs and Security. The researchers’ goal was to explore the significance of schools for local neighborhoods and their development in somewhat greater depth and thus to devise a practice-based foundational research project, a so-called DoRe project.

I will now first present the discussion of these themes within the field of sociology and the local context of the study. In the following section, I will explain the methodology, followed by the most significant results. I will conclude my remarks with an attempt to bring these results together into two theses.

The Theoretical Background and Discipline-Specific and Local Context of the Study

Context of the Study

School as a Reflection of the Local Neighborhood and Thus Part of the Problem

“Every deficit and problem to be found in a neighborhood’s social structures will be reflected in the kindergarten and school” (Gerhard & Fennekohl, 2000, p. 277). And the following statement is also true: Show me where you live and I’ll show you who you are and who you’ll be. This is why many families who have the economic means move away from problematic neighborhoods and into more well-to-do areas of a city. In the field of socioeconomics, such processes of realignment and concentration of the population are known as segregation. The result of these segregation processes is a concentration of problem factors in local neighborhoods and schools (Baur, 2013). School is thus to be seen, on the one hand, as part of the problem.

Or: School as a Solution to Sociospatial Problems

Yet researchers also see school as playing an integrative role and consider it a key local factor in neighborhoods that demonstrate “an above-average concentration of problems in comparison to the city as a whole” (Becker, 2003, p. 72). In order to have an integrative effect, the school must open itself to the local neighborhood and work together with other institutions (such as child and youth services or neighborhood support services). Neighborhood development processes can be advanced by integrating schools in these processes.

Schools are gaining in importance as the central focus of community life in neighborhoods and districts. They leave their mark on how the district is seen as a place to live; their character and quality open up paths for district development, though blocking others. Not only the churches but also the parish halls and community centres are plummeting in their significance as places of community life and as the central focus of urban districts. (Burgdorff, 2017, pp. 103–104)

Other reasons for education’s rising status as an element of integrated urban development strategies also include municipal challenges such as demographic change, tight public finances, growing tendencies towards the segregation and polarization of society, and increasing regional competition as well as reurbanization (Coelen, Heinrich, & Million, 2017, p. 6).

From this perspective, school is to be viewed as part of the solution.

In the very much contradictory discussions on the subject, it remains unclear what aspect of school the researchers are referring to specifically. School as part of an educational system? Or school as a specific location, a building in a local context? It is equally unclear what the relationship is between school and the local neighborhood. Does the neighborhood play a positive or negative role in the children’s development? Is the connection between the residential area and the school district part of the solution or part of the problem? If one consults recent publications on city and school development, it becomes clear that little objective knowledge on this subject exists (Baur, 2013; Freytag & Jahnke, 2015; Huxel & Fürstenau, 2017; Mack, 2017; Million, Heinrich, & Coelen, 2017; Ottersbach, 2016).

For the DoRe project, researchers looked at school in terms of its sociospatial context and took the relational fabrication view of space discussed above as a point of departure. With the help of the mental figure of the St. Gallen model for the creation of social spaces (see Fig. 15.1), it is possible to develop different structural approaches (Reutlinger, 2017).

Is school to be understood as a building, that is, a place and its material properties? Or should focus be placed on the actions and basic biographical and behavioral characteristics of the actors involved? Or are such structural preconditions as laws or the institutional framework of the administrative structures of primary interest?

For this project, I utilized a child-oriented perspective to examine such fabrication processes as a starting point for the St. Gallen model for the creation of social spaces (Reutlinger, 2017) (see Fig. 15.2).

My aim was to ascertain how children form connections between structures (i.e., house rules, educational ideas, general principles), locations (i.e., concrete things in the physical, material world) and the actors involved—the human beings (Reutlinger & Wigger, 2010). What special features does school have as a social space from a child’s perspective? What does school mean as a system with its unique rules and structures? What importance does the concrete location in a specific territorial context assume and what significance do specific persons like fellow students or teaching staff have for children? And finally: How do children perceive their school and neighborhood and what relationships exist between these “two worlds?”

In the empirical implementation of the research initiative, I set out to reconstruct two primary schools located in neighborhoods (city sections) that are very distinct in both their architecture and residential population in terms of their sociospatial contexts. This reconstruction would provide initial orientation for forms of cooperation between neighborhood and school, that is, between actors from the fields of urban planning, local development, and school (such as school social workers). Using this as a basis, I will draw conclusion related to these forms of cooperation in the context of overall city development.

Context of the Study: Local Context

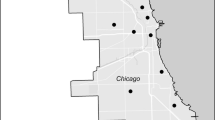

The Swiss city I examined has divided its municipal territory into different neighborhoods, development districts, and school districts, which are partially overlapping and vary according to the perspective of the actors and the administrative logic. In the project “School as Social Space,” two different city sections—A and B—were chosen, where completely different divisions and classifications play a role: The school district does not match with the geographical divisions used by the Parks Department, and neighborhood organizations also define their catchment areas differently (Fritsche et al., 2011). The geographical areas examined in the study follow the logic of the classifications used by the Social Services Department, upon which local services, for example, are also based. Statistically,Footnote 3 these are the city’s most populous neighborhoods (Fritsche et al., 2011). A large portion of Neighborhood B has been labelled an urban development area (see Fig. 15.3). As such, it and the school are seen as having a problematic social structure (“social hot spot”). Statistical data, however, seem to indicate that the two neighborhoods studied are relatively average in many regards, with no remarkable tendencies.

Spatial structures of Neighborhood A and Neighborhood B. Reprinted from Fritsche et al. (2011), pp. 74–80. Copyright 2011 by Caroline Fritsche, Peter Rahn, and Christian Reutlinger. Reprinted with permission

Methodology

For the purposes of data collection, we visited four classes in both School A and School B during the project period (2007–2010). In the course of the visits to the four classes (Grades 3 and 6 in School A and School B, that is, 9- and 12-year-old students), the children drew subjective maps (Daum, 2010; Deinet & Krisch, 2009). We asked them to draw locations where they spend time and that are important to them on a piece of paper. They were to write what they do at these locations and who they meet there. They were also to name the locations that they avoid. In addition, the children indicated their place of residence and favorite location on a large map of the neighborhood. Finally, we asked the children to write an essay on school as a location for learning and spending free time. The reconstruction of the maps was conducted by topic analysis—the topics of the maps were named and their characteristics worked out. In this manner, six topics became visible in the material: family, free-time activities with peers, places to be avoided, organized children’s culture activities, being alone, and eventually school. These topics should enable the comparison of the two schools and grade levels to elucidate both the typical differences and similarities between the groups (Fritsche et al., 2011).

Key Results: Analysis of the Subjective Maps

Theme of School

In terms of the significance of the respective primary schools in each neighborhood, the children generally did not place the building at the center of the map but instead drew it on the edge or even on the reverse side of the paper. They often marked the school in red as a place to be avoided (see Fig. 15.4).

Yet the children ascribed different characteristics to their respective school.

-

School A: Only 6 of the 22 older school students (Grade 6) from School A made mention of school. One girl and two boys referred to more interactive elements: They noted sport instruction in the gymnasium, “school with friends,” and “school with the class.” Three other girls cited playing on the school grounds as positive, though one commented that in reality this is not a school-related activity. Of the 20 younger children (Grade 3) in the same school, 10 mentioned school, here placing an emphasis on learning. Two girls and one boy emphasized interactive aspects, as they stated that in school they learn together with the rest of the class. Two boys, on the other hand, rated activities that they engage in alone at school as positive. One said that he does arithmetic alone at school, while the other stated that he reads alone in the classroom reading corner and plays alone during breaks in the schoolyard. One girl drew the school and simply wrote the word “school.” Another created a connection between school and home by stating that she completes her homework alone at home. Evidently, however, the children are not in agreement on this point: Two boys classified obligatory homework as negative.

Thus, the children do not directly describe school as important. It appears to serve a functional role for the children but not to have any great significance: They learn at school and for school as well as form friendships at school, which are relevant for what they do in their free time.

-

School B: The students of School B view school somewhat more critically: The 19 younger students (Grade 3/4) cited it only 6 times as something positive, 11 times as something negative. The negative ascriptions remain to some extent vague: One boy referred to the school building itself, another simply wrote “School B,” three girls and one boy wrote nothing but the word “school.” The latter seems to refer to classroom instruction, as the boy considered it positive that at school he can meet all his classmates and a girl cited “school building with friends” as positive. Five girls expressed a critical attitude towards instruction, as they listed math or arithmetic as negative, four times in connection with school itself. Two girls who view school critically also see its positive aspects: One listed “school” trips to the swimming pool as positive, the other cited school as a place to spend free time as positive. Four boys did the same. For them, the schoolyard is an attractive place to meet friends.

All 18 older school students (Grade 5/6) from School B included school in their subjective maps: Eight students labelled it as a positive location, 10 as negative. A few criticized math and learning. The necessities of getting up early and doing homework were mentioned more frequently. They cited boredom at school most frequently of all, while four students stated that they do not like members of the teaching staff. They mentioned the interactive aspects of school as positive, including the learning that takes place both in school (“school: learning”) and at home, in addition to homework assignments. Only two boys mentioned free-time activities.

The students from School B thus view school more critically, though the older students’ standpoint is more nuanced than that of the younger students. They do not just tolerate school in its current form but criticize the content presented there as well as the staff and structures that do not satisfy their needs. This makes clear that their expectations of school are quite high. Overall, their criticism indicates that they feel that school possesses a central life function but that it does not fulfill this function very well.

Generally speaking, we are able to attribute the following functions to school from a subjective perspective: School has an interactive element (1). Emphasis is placed on activities engaged in with others, community is experienced both during instruction and while playing on the school grounds. School is also a place of learning (2). Learning can be experienced collectively, but also as an individual pursuit or as a nonspecific activity. School can, however, also attain significance above and beyond instruction in that the school grounds are used as a meeting place for collective free-time activities, as a living location (3). School also has effects on the children’s home life—or is extended into their homes, as it is generally at home that they do their homework assignments alone (4) and study. However, school also elicits dislike or distance (5): Boredom, homework, getting up early, learning in general or—especially for girls—mathematics. Certain members of the teaching staff also instil in students a dislike of school.

Reciprocal Effects of School and Neighborhood

-

School/Neighborhood A: School A is located in a neighborhood that offers many opportunities for children, as is reflected in the subjective maps (see Fig. 15.5).

The students there thus pursue the majority of their free-time activities in the neighborhood itself. They meet with other children in the forest to build shelters or make fires or they go to the neighborhood swimming pool (see Fig. 15.6).

Only a few of the older children extend their activities to the city center, for example by meeting friends at McDonalds (see Fig. 15.7). The school grounds play no significant role as a location for free-time activities.

-

School/Neighborhood B: Striking about School B is that the children often use the sport facilities and playgrounds there in their free time (see Fig. 15.8).

One might assume that this attractiveness is due to the fact that important themes are addressed at school. This is, however, not true. The popularity of the school grounds is far more a result of the lack of opportunities for free-time activities elsewhere in Neighborhood B. As a result, students engage in free-time activities on the school grounds before and after school, playing games or doing sports. They mentioned few neighborhood locations apart from the school playground and the neighborhood streets. Furthermore, the children avoid many locations, such as an abandoned petrol station.

Club activities and excursions to the swimming pool generally take place outside of the neighborhood. As a result, even younger children travel to the city center with their peers (see Fig. 15.9).

Summary

Neighborhood A

-

There are many opportunities in the neighborhood itself.

-

The school offers no especially attractive features.

-

However, the school is not a place to be avoided.

-

Children take advantage of opportunities in their neighborhood.

Neighborhood B

-

There are few opportunities in the neighborhood itself.

-

By contrast, the school building is of interest.

-

The school as an institution nevertheless elicits a negative attitude and distance.

-

Children seek orientation more frequently and at an earlier age in other sections of the city, including the city center.

General Observations About Both Neighborhoods

Children in both parts of the city—though only few of the younger children in Neighborhood B—mentioned organized free-time activities for children like Scouts and sport clubs. Children in both parts of the city generally travel to these free-time activities alone (not depending on their parents to drive them) or with peers. They travel by foot, scooter, kickboard, bicycle, and bus.

The family or home has special importance above all for younger children as a place of emotional support where spatial appropriation is made possible (see Fig. 15.10).

Engaging in an activity together with peers or the family is far more appealing to children than doing something alone. The solitary activities mentioned are: Reading alone at home, playing games or doing a jigsaw puzzle, taking the dog for a walk, X-Box and computer games, watching television, playing in their rooms, and “sitting in the wardrobe and lying around with my cat or by myself,” going to the swimming pool or playground, walking in the forest, or going to church or the garden. Home is the preferred location for pursuing activities alone (see Fig. 15.11).

The first thesis can be formulated as follows: The primary effect of school on everyday life is found in the interaction between students in their classes. The quality of this interaction leads to the appropriation of space outside of school. Neighborhood peer relationships are supplemented by school relationships and extend the space that children spend time in and explore in their free time.

Key Results: Analysis of the Essays

The analysis of the subjective maps would seem to suggest that if asked to freely describe their everyday existence, the children of both age groups would not say that school occupies a central role in their lives. When instructed to write an essay in 20 min about school as a location of learning and playing, the children were specifically prompted to reflect on school. They were to explain what school means to them, what they do there, what they enjoy about school, what they dislike, and what could be better.

School as a Facilitative Location

The children initially give school an abstract, future-oriented meaning: They see learning as necessary in order to have success later in their careers. This motivates some children to learn even if they do not really like school. Generally, this abstract aspect does not exist in isolation, but is supplemented by a concrete emotional element: School offers a space for experiences. The aspect of interaction that the children expressed in the subjective maps is also discussed in the essays.

School as an Educational Space

The specific location offers corresponding opportunities—it is ruled by an authority that guarantees a certain structure in terms of the learning setting and the type of play that can be engaged in. This authority is personified by the member of the teaching staff, who the children see as responsible for the functioning of the school. School defines the day’s structure, offers a wide variety of things to do, is a place of activity or a place where certain activities are possible, and provides a space where children can be children.

Differences in the Themes Raised by the Students of the Two Schools

-

School A: The children cited the positive aspects of school. School offers something, does not present limitations. For the most, the children equated school with classroom instruction and thus limited it to the physical location and to school hours. When viewed in their entirety, these students’ essays give the impression that school has nothing to do with their everyday existence: “I would come here more often if there were more playing opportunities” or “I personally get all my work done in school and prefer play in the park,” because “in my spare time I am undisturbed and can rest well and sleep and shop.” In school, learning is most important and is supplemented by active and affective components. School is a self-contained event that takes place during the hours of instruction. The students thus accept and tolerate school without objection.

-

School B: For these students, school also exists for the purposes of learning, yet their expectations clash with the conditions offered by the school. The students’ expectations are quite heterogeneous—this is especially true of the older students. The themes they raised indicate that they view school and free time as separate worlds. Yet they express the idea that school is a living location that serves as a link between classroom instruction and free time. Ultimately, a pattern of critical distance can be reconstructed according to which school and instruction take up too much space and authority is criticized in different manners. The students are unanimous in their criticism that school does not fully reach its facilitative potential. The reasons for this and suggestions for improvement are quite diverse. School should, for example, provide a full-day structure; learning situations should facilitate learning more effectively; learning should be more varied, more up to date, more fun; girls and boys should not be put together in a single class. The students criticized the school rooms as sharply as the school’s image, including both the school’s poor physical condition and its inadequate website. Furthermore, the students are given insufficient support in their own conceptions of their identity.

The second thesis to be discussed can be summarized as follows: School A functions as a closed system, outside of which school is of no significance and inside of which everyday life is of no significance. Two worlds that are unconnected, and do not interact. In School B, the boundaries between school and everyday life and between school and the neighborhood are porous. The worlds interact and school is ascribed a function that shapes the children’s present lives.

Conclusion

In the appropriation patterns evident in both neighborhoods, it is clear that children are now growing up with a range of ideas about what space means. Living in space is now associated with the experience of being able and required to constantly adapt to different places and conditions. As formulated by the sociologist Martina Löw, students experience school “not as uniform but as varied, not as continuous but as discontinuous, not as fixed in place but as fluid” (Löw, 2001, p. 266). And what consequences can be derived from the empirical results of the discussed study? I will draw my conclusions following three considerations:

-

First of all, it seems to be important to not only focus on the number of places and their condition when considering what potentials for appropriation neighborhoods are equipped with. In addition, the subjective approach via children shows what is paramount are the possibilities, which should be provided at certain places: Possibilities for independent activity, for confrontations with other individuals, and for educational processes.

-

Secondly, this means that professionals must consider carefully how we provide these possibilities or how to direct them through constructional or pedagogical measures. Constructional elements should not be too obvious and should not limit the potential for change. Rather, these elements should enable children to occupy them with their own required functions repeatedly. However, the demand for possibilities also concerns education. Children introduce various themes to their places: At home, at the playground, or at the youth center. At these places, they should be enabled to work on their themes. In this way, school is more than just a place for learning and knowledge transfer, but rather a place to cope with life themes. Education should adapt to this.

-

Thirdly, the results also show that children are not determined by the (constructional and social) circumstances. In fact, they are able to create their own world by converting places, overcoming boundaries, conquering places in their city independently, and thereby developing broad networks of places.

This leads me back to Rico, my protagonist from earlier. This is precisely his problem: If spaces were rigid and uniform and governed by clear rules, things would surely be easier for him. But because they are not, he depends on his Post-it notes, feels lost when something unexpected happens, and in general finds it terrifying to independently appropriate the great big world. With the help of people like his friend Oskar and the teacher Wehmeyer, however, Rico’s world expands in the course of the story. Or, metaphorically speaking, these relationships enable him to break out of the container room. When Oskar is kidnapped by the so-called “Mister 2000,” Rico overcomes his fear and sets off alone to distant Berlin Tempelhof to rescue his friend.

Only towards the end did it start to get tricky: from one street to the next, then more crossings, more traffic lights, and all the while the bingo balls were clattering around in my head, saying the same thing: You’ll never find your way back home, you’ll never find your way back home … Well, we’ll see! (Steinhöfel, 2008, p. 135)

His courage is ultimately rewarded, as he saves Oskar from the clutches of his kidnapper, the sinister “Mister 2000.” Rico is even able to enjoy the motorcycle ride with his teacher Wehmeyer around the outskirts of Berlin:

The cool air blew in under my shirt, making it flutter, and Wehmeyer’s old worn black leather jacket had a smell to it that seemed to say that nothing bad could ever happen in the world. I felt an urge to throw my arms up into the air and shout out with joy, but I didn’t want to go flying from the bike… I pressed myself against Wehmeyer’s leather jacket again, sniffed all the security inside it, and wished that I could buy a cologne that smelled like that. (Steinhöfel, 2013, pp. 21–22)

Notes

- 1.

Steinhöfel’s books exist only in German, so the quotations have been translated by an external translator.

- 2.

- 3.

In order to anonymize the name of the city, I cannot publish the source of the communal statistics.

References

Baur, C. (2013). Schule, Stadtteil, Bildungschancen: Wie ethnische und soziale Segregation Schüler/-innen mit Migrationshintergrund benachteiligt [School, district, educational opportunities: How ethnic and social segregation discriminates against pupils with a migration background]. Bielefeld, Germany: Transcript.

Becker, H. (2003). “Besonderer Entwicklungsbedarf”: die Programmgebiete der Sozialen Stadt [Special need for development: the program areas of the social city]. In Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik (Ed.), Strategien für die Soziale Stadt: Erfahrungen und Perspektiven: Umsetzung des Bund-Länder-Programms “Stadtteile mit besonderem Entwicklungsbedarf:die soziale Stadt” (pp. 56–73). Berlin, Germany: Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik.

Burgdorff, F. (2017). The interrelationship between education and urban development. In A. Million, A. J. Heinrich, & T. Coelen (Eds.), Education, space and urban planning: Education as a component of the city (pp. 103–108). Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-38999-8

Coelen, T., Heinrich, A. J., & Million, A. (2017). Common points between urban development and education. In A. Million, A. J. Heinrich, & T. Coelen (Eds.), Education, space and urban planning: Education as a component of the city (pp. 1–15). Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-38999-8

Daum, E. (2010). Subjektive Landkarten: Raumerfahrung [Subjective maps: spatial experience]. In L. Duncker, G. Lieber, N. Neuß, & B. Uhlig (Eds.), Bildung in der Kindheit: Das Handbuch zum Lernen in Kindergarten und Grundschule (pp. 254–256). Seelze, Germany: Klett/Kallmeyer.

Deinet, U., & Krisch, R. (2009). Subjektive Landkarten [Subjective maps]. sozialraum.de, 1/2009. Retrieved from http://www.sozialraum.de/subjektive-landkarten.php

Deinet, U., & Reutlinger, C. (Eds.) (2004). “Aneignung” als Bildungskonzept der Sozialpädagogik: Beiträge zur Pädagogik des Kindes- und Jugendalters in Zeiten entgrenzter Lernorte [“Appropriation” as an educational concept of social pedagogy: Contributions to the pedagogy of childhood and adolescence in times of deprived learning places]. Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-80966-7

Deinet, U., & Reutlinger, C. (Eds.) (2014). Tätigkeit—Aneignung—Bildung: Positionierungen zwischen Virtualität und Gegenständlichkeit [Activity—appropriation—education: Positioning between virtuality and objectivity]. Sozialraumforschung und Sozialraumarbeit: Vol. 15. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-02120-7

Freytag, T., & Jahnke, H. (2015). Perspektiven für eine konzeptionelle Orientierung der Bildungsgeographie [Perspectives for a conceptual orientation of educational geography]. Geographica helvetica, 70, 75–88. https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-70-75-2015

Fritsche, C., Rahn, P., & Reutlinger, C. (2011). Quartier macht Schule: Die Perspektive der Kinder [The neighborhood makes the school: The children’s perspective]. Sozialraumforschung und Sozialraumarbeit: Vol. 5. Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-94019-9

Gerhard, R., & Fennekohl, E. (2000). Gemeinschaftsgrundschule Roncallistrasse: Stadtteilkonferenz: Ein Stadtteil hilft seinen Kindern [Community elementary school Roncallistrasse: district conference: A district helps its children]. In R. Bendit, W. Erler, S. Nieborg, & H. Schäfer (Eds.), Kinder- und Jugendkriminalität: Strategien der Prävention und Intervention in Deutschland und den Niederlanden (pp. 277–281). Opladen, Germany: Leske + Budrich.

Graumann, C.-F. (1990). Aneignung [Appropriation]. In L. Kruse, C. F. Graumann, & E.-D. Lantermann (Eds.), Ökologische Psychologie: Ein Handbuch in Schlüsselbegriffen (pp. 124–130). Munich, Germany: Psychologie VerlagsUnion.

Harvey, D. (1973). Social justice and the city. London, UK: Edward Arnold.

Harvey, D. (2005). Space as a key word. In D. Harvey, Spaces of neoliberalization: Towards a theory of uneven geographical development (pp. 93–115). Hettner-Lecture: Vol. 8. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner.

Hüllemann, U., Reutlinger, C., & Deinet, U. (2017). Aneignung als strukturierendes Element des Sozialraums [Appropriation as a structuring element of social space]. In F. Kessl & C. Reutlinger (Eds.), Handbuch Sozialraum. Grundlagen für den Bildungs- und Sozialbereich. Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-19988-7_24-1

Huxel, K., & Fürstenau, S. (2017). Sozialraumorientierte Schulentwicklung in der Migrationsgesesllschaft: Konzeptionelle Überlegungen und eine Fallstudie [Social space-oriented school development in the migration society: Conceptual considerations and a case study]. In T. Geisen, C. Riegel, & E. Yildiz (Eds.), Migration, Stadt und Urbanität: Perspektiven auf die Heterogenität migrantischer Lebenswelten (pp. 261–277). Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-13779-3_14

Kessl, F., & Reutlinger, C. (Eds.) (2010). Sozialraum: Eine Einführung [Social space: An introduction] (2nd ed.). Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-92381-9

Löw, M. (2001). Raumsoziologie [Sociology of space] (Vol. 1506). Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Suhrkamp.

Mack, W. (2017). Education in the city from the perspective of social spaces. In A. Million, A. J. Heinrich, & T. Coelen (Eds.), Education, space and urban planning: Education as a component of the city (pp. 205–211). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-38999-8_19

Million, A., Heinrich, A. J., & Coelen, T. (Eds.). (2017). Education, space and urban planning: Education as a component of the city. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-38999-8

Ottersbach, M. (2016). Bildung in marginalisierten Quartieren [Education in marginalized neighborhoods]. In M. Ottersbach, A. Platte, & L. Rosen (Eds.), Soziale Ungleichheiten als Herausforderung für inklusive Bildung (pp. 17–30). Wiesbaden, Germany: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-13494-5_2

Reutlinger, C. (2007). Territorialisierungen und Sozialraum: Empirische Grundlagen einer Sozialgeographie des Jugendalters [Territorialization and social space: Empirical foundations of a social geography of adolescence]. In B. Werlen (Ed.), Ausgangspunkte und Befunde empirischer Forschung (Sozialgeographie alltäglicher Regionalisierungen: Vol. 3. Erdkundliches Wissen) (Vol. 121, pp. 135–164). Stuttgart, Germany: Franz Steiner.

Reutlinger, C. (2012). Aneignung [Appropriation]. In S. Günzel (Ed.), Lexikon der Raumphilosophie (p. 23). Darmstadt, Germany: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Reutlinger, C. (2017). Machen wir uns die Welt, wie sie uns gefällt? Ein sozialgeographisches Lesebuch [Do we create the world the way we like it? A social geographic reader]. Zurich, Switzerland: Seismo.

Reutlinger, C., & Brüschweiler, B. (2016). Sozialgeographien der Kinder: eine Spurensuche in mehrdeutigem, offenem Gelände [Social geography of children: a search for clues in ambiguous, open terrain]. In R. Braches-Chyrek & C. Röhner (Eds.), Kindheit und Raum (pp. 37–64). Kindheiten. Gesellschaften: Vol. 2. Opladen, Germany: Budrich.

Reutlinger, C., & Wigger, A. (2010). Das St. Galler Modell: Eine Denkfigur zur Gestaltung des Sozialraums [The St. Gallen model: A figure of thought for designing social space]. In C. Reutlinger & A. Wigger (Eds.), Transdisziplinäre Sozialraumarbeit: Grundlegungen und Perspektiven des St. Galler Modells zur Gestaltung des Sozialraums (pp. 13–54). Transposition: Ostschweizer Beiträge zu Lehre, Forschung und Entwicklung in der sozialen Arbeit: Vol 1. Berlin, Germany: Frank & Timme.

Steinhöfel, A. (2008). Rico, Oskar und die Tieferschatten [Rico, Oscar and the deeper shadows]. Hamburg, Germany: Carlsen.

Steinhöfel, A. (2013). Rico, Oskar und das Herzgebreche [Rico, Oscar and the heartbreak]. Hamburg, Germany: Carlsen.

Werlen, B., & Reutlinger, C. (2005). Sozialgeographie [Social geography]. In F. Kessl, C. Reutlinger, S. Maurer, & O. Frey (Eds.), Handbuch Sozialraum (pp. 49–66). Wiesbaden, Germany: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Reutlinger, C. (2019). The Relationship Between School and Neighborhood: Child-Oriented Perspectives on Educational Locations. In: Jahnke, H., Kramer, C., Meusburger, P. (eds) Geographies of Schooling. Knowledge and Space, vol 14. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18799-6_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-18799-6_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-18798-9

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-18799-6

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)