Abstract

This chapter offers an overview of primary education in Togo, spanning the two last decades. Togo made important progress. School enrollment increased considerably and the percentage of school-aged children not attending school dropped significantly. At the same time, learning outcomes give reason for concern as the quality of education appears to be wanting. This challenge is not specific to Togo; it affects other African school systems as well though its seriousness varies from country to country.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

2.1 Primary Education Since the Year 2000

Togo is a sovereign state in West Africa bordered by Ghana to the west, Benin to the east and Burkina Faso to the north. It extends south to the Gulf of Guinea, where its capital Lomé is located. Togo covers 57,000 square kilometers making it one of the smallest countries in Africa and has a population of less than 8 million. The country has known a long period of economic decline and political upheaval that started in the early 1990s and which formally ended with the parliamentary elections of October 2007. The education sector suffered greatly during this period. Financial constraints prevented the renewal and upgrading of the teaching profession and the renovation or construction of education facilities at a pace sufficient to meet constantly growing needs for education.

With the limited spending of the public sector in education and as the crisis deepened, parents responded by sending their children to private schools. So, while between 2000 and 2005 the number of students attending public primary school increased by 5%, the number of students going to private schools (for profit and religious establishments, but also local initiative schools referred to in French as École d’Initiative Locale (EDIL)) increased by 20%. Nationwide, 40% of students attended a private–public school in 2000; by 2005 this had increased to 43%. In rural areas one saw a proliferation of EDIL schools, which relied entirely on local community financing and family support. The importance of private education is illustrated by the fact that in the year 2000 more than half the schools in the Savanes, one of the poorest regions of the country, were non-public 43% were of the EDIL type; another 17% were private schools. While in other rural areas public provision continued to be more important than private provision, in urban areas private provision outstripped public provision as well. In the year 2000 but also in 2010 the proportion of urban students enrolled in private institutions was around 66%.Footnote 1

As donor support was withdrawn during the crisis the public education sector relied entirely on financing by the State. Capital spending was reduced, hiring was limited and the education system started to rely more on so-called contract teachers—temporary and auxiliary teachers who work for a fraction of the wages of civil servants but who are also less qualified (UNESCO, UNICEF 2014). These developments explain, as will be demonstrated later, why the quality of education declined so rapidly during this period.

Parents had good reason to opt for private alternatives as the quality of public education was deteriorating as evidenced by the fact that even though the number of students increased in public schools, the number of teachers declined by 12%, resulting in rising student–teacher ratios (from 1:36 in 2000 to 1:43 in 2005). On a positive note the teachers that left tended to be those with less education themselves, those with a primary or secondary school diploma, while the number of teachers with a baccalaureate increased. As a consequence, the ratio of teachers with only a primary or secondary school diplomas decreased from 80 to 75%. In private (non-EDIL) schools, the increase in teachers kept pace with the increase in students and student–teacher ratios remained constant at 1:32. In private schools too, teacher qualifications went up, in a way that was more pronounced than in public schools. Had in 2000 some 75% a primary or secondary school diploma, by 2005 this percentage had dropped to less than 50%.

During the crisis years, Togo’s citizens thus demonstrated to value education. Remarkably throughout the years of economic hardship enrollment levels remained high in comparison with most other West African countries. In fact, they even increased. The net primary school enrollment rate for children aged 6–11 years rose from 63% in 2000 to 73% in 2006 and the gross rate for the same age group increased from 103 to 115%.

Encouraged by the success of the 2007 elections and the new government’s reform platform, which included the abolition of school fees starting in the 2008/2009 school year and the gradual integration of EDIL schools in the public school system, donors reengaged with the country after more than 15 years of providing limited assistance. By 2010 an strategic Education Sector Plan (PSE) had been formulated and adopted and money from external education financiers started flowing again.Footnote 2

Following the introduction of free primary education, enrollment rates increased rapidly. Additional teachers were hired and by 2016 the number of public school teachers had almost doubled from 14,000 in 2006 to over 24,000. As student numbers increased in lock-step, student–teacher ratios did not change, and remained at 1:43. The education background of teachers did improve however and the fraction of teachers with a primary or secondary school diploma dropped to 62%. As public-primary education became free, the number of students attending private schools stabilized at around 450,000 students, while the share of students attending private schools dropped to 30% in 2016—down from 43% a decade earlier. Unlike in public schools the qualifications of private-school teachers did not improve further and the student–teacher ratio, though still favorable relative to public schools, increased to 1:34 (up from 1:32 a decade earlier).

Not only did more children receive an education, the new policies of absorbing EDIL schools in the public school system and abolishing school fees were pro-poor as the children that benefited most originated from the poorest households in rural areas. And as more children were going to school (net enrollment reached 94% in 2016/2017), other, spatial and gender, inequalities reduced as well.

Remarkably for a system that had to deal with a large influx of new students and the absorption of EDIL schools, internal efficiency also went up: many more children passed their primary school leaver exam and fewer children repeated their grade or dropped out completely. So, in almost all respects the education reforms initiated in 2007 were a resounding success. The number of children who completed primary school doubled over the course of a decade, an increase that was achieved while improving the efficiency of the education system and without affecting pass rates in any negative way. If anything, a larger fraction of children was successful at their exam.

2.2 Closer Look at the Introduction of Free Primary Education

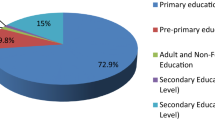

Togo’s educational system is divided into four levels: (i) a three-year pre-school cycle designed for 3–5 year olds; (ii) a six-year primary cycle designed for 6–11 year olds; (iii) a seven-year secondary education cycle designed for 12–18 year olds, consisting of a four-year junior level and a three-year senior level and (iv) a higher education system. There is also technical and vocational training at the junior and senior secondary levels and literacy training. The focus of this book is on the six-year primary cycle, which can be sub-divided into three groups: CP1 and CP2, the first two years, CE1 and CE2, years three and four, and CM1 and CM2, years five and six. At the end of year six, students sit for an end of school exam, the CPED.

Prior to the start of the 2008/2009 school year, which normally runs from September till June the following year, the Government of Togo announced it would abolish school fees for primary education. After a decade of slow growth in which increases in enrollment remained below the population growth trend, the introduction of free primary education led to a rapid increase in enrollment. The biggest increase was registered during the first year primary education was free, after which followed a period in which primary school enrollment largely kept pace with population growth (Fig. 2.1). The inflow of new students came as a shock to the system. Between 2006/2007 and 2008/2009 the number of students attending public primary school increased from 590,000 to 777,000 a 32% increase. In the course of 2 years, 500 new schools and 2300 teachers were absorbed into the public education system, an increase of 19 respectively 17%. Not all these schools were newly constructed, nor were all additional teachers new hires. Some 228 newly incorporated schools were former EDIL schools that were now absorbed into the public school system along with their students and teachers.

Table 2.1 illustrates the changes the primary school system went through with the introduction of free primary education. To this end we compare the school system in the year shortly before the reforms were introduced (2006/2007) with the system 10 years later. Over the course of a decade, the number of students increased by almost 50% from one million, to a million and a half. Schools became bigger on average as the number of schools increased by less than the increase in the number of students: 31%. Also, the number of students per classroom and the number of students per teacher increased, though not by much as the number of classrooms increased by 42% and the number of teachers by 46%.

As one might expect, the share of students going to public schools increased. Surprisingly, though, this increase did not come at the expense of private (religious and non-religious) schools which, unlike public schools did not abolish school fees. The increase in the fraction of students going to public schools is largely the results of EDIL schools being absorbed in the public school system. Noteworthy is that amongst the private schools, Catholic schools became less popular. Private non-religious schools picked up the students that stopped going to Catholic schools.

As teaching staff is a critical input into education, it is worth considering how its composition evolved before and after the introduction of free primary education. Of note is that both in public and private schools the number of teachers increased substantially. Moreover, within the public school system there is a strong weakness due to the composition of teachers with respect to their contract and payment. The public system relies more substantially than the private one on teaching assistants/volunteers and temporary staff, staff who tend to get paid half or less than half, compared to what their civil servant colleagues make.Footnote 3 In private education establishments such staff made up more than 10% of the total staff complement in 2006/2007 and in 2016/2017 only 2%. Compare this to the public school system where half the teachers are assistants or people with temporary contracts. The private school system also increased the fraction of female staff, from 14% in 2006/2007 to 21% in 2016/2017. In the public sector little changed: female teachers make up some 14% of the total teaching complement (Table 2.2).

Such major reforms come with growing pains, if only because all of a sudden, a large cohort of students entered CP1. Between 2006/2007 and 2008/2009 the number of children in public school CP1 increased from 127,000 to 208,000, a 64% increase. As this bulge of students worked itself through the primary school system, the situation gradually normalized in subsequent years. Consequently, four years later, in 2012/2013, the number of students in CP1 was 139,000. Student–teacher ratios, already high at 44.4 students per teacher in 2006/2007 increased to 49.7 two years later and returned to 44.4 by 2012/2013.

Despite the stresses under which the education system was put, the system’s internal efficiency improved across the board. In its wake, almost all gender disparities were eliminated as well. The fraction of six-year-old children attending school increased significantly, especially after 2012. The fraction of pupils not passing to the next grade declined dramatically from almost one in four between 2006 and 2008 to one in thirteen by 2016/2017 following the adoption of a decree at the beginning of the 2012/2013 school year which limited the ability of schools to let pupils repeat grades. Also the number of pupils who abandoned school dropped (Table 2.3).

The increase in enrollment reduced inequalities. Poverty in Togo broadly follows a north–south axis with poverty being worst in the north and lower in the south. Like poverty, and before the abolition of primary school fees, attendance rates in regions in northern Togo (Savanes and Kara) were much lower than elsewhere in the country. This can be illustrated with survey data, showing that in 2006 attendance rates in the northern regions were as low as 52% in 2006 in Savanes. By 2013/2014 attendance rates in this region had increased by 25% age points to 77%. As a consequence the gap with the best performing region (Lomé) reduced from 40% in 2006 to 12% in 2013/2014. The large increase in school enrollment and attendance turned out to be a great equalizer. Girls caught up relatively to boys, children living in poor households reduced the gap relative to those living in better-off households as did those living in rural areas. Inequalities did not fully disappear, but by 2013/2014, five years after introducing free primary education, they had reduced considerably as the difference between the best (Lomé) and the worst (Savanes) performing region dropped from 40 to 18%, between rural and urban areas from 17 to 6% and between the poorest and wealthiest quintile from 25 to 9% (Fig. 2.2).

A decade after the introduction of free primary education, in 2017, almost 100,000 children in public primary school successfully completed their primary school leaver exam. Some 130,000 pupils sat for the exam, implying a success rate of 77%. This was a remarkable achievement, as over the course of a decade the number of students who successfully completed primary school had effectively doubled. In 2006/2007 49,000 passed the CEPD exam out of 71,000 who sat for it, a pass rate of 69%. As pass rates improved, they improved more for girls whose likelihood of passing improved from 64 to 75%, than for boys (from 71 to 78%). These achievements are even more remarkable when one realizes that not only pass rates improved, students arrived in grade 6 faster as grade repetition rates had reduced remarkably. Where in 2006/2007 one in four children repeated their grade, a decade later this had dropped to less than 10%.

Such a reform effort does not come cheap. In fact, between 2006 and 2015 the budget for primary education almost quadrupled from FCFA 14 billion in 2006 to FCFA 56 billion in 2015. So while the number of public students almost doubled during that period, real spending per student increased as well, by as much as nearly 80% from FCFA 23,000 to FCFA 43,000. This was possible, in part, because during this period the economy of Togo recovered from crisis levels. GDP growth became positive again and revenue collection improved considerably. Expressed as a fraction of GDP spending on primary education almost doubled from 1.3 of GDP in 2006 to 2.4% in 2015, but as revenue collection improved rapidly following the crisis the increase as expressed in percent of the budget was less (from 5.6% in 2006 to 6.8% in 2015). In fact, for most of the period the share of primary education in public spending remained relatively constant hovering around 7% of revenue collected (Fig. 2.3).

As spending increased a sector that had neglected investments during the crisis years, ramped up. The investment budget increased by a factor 8 from around FCFA 2 billion in 2008 to more than 16 billion in 2011, a level at which it remained for the next 3 years, before starting to taper off in 2014 (see Annex Table 2.4). As a result, the total number of classrooms increased from 22,272 in 2009 to 24,926 in 2016, while a number of classrooms made from stamped earth were converted into more permanent materials. Despite these investments, considerable regional differences in the type of construction materials used for schools continued to persist: particularly in the poorer regions of Plateaux and Savanes the fraction of schools constructed out of permanent materials tends to be low. These are the same regions were in the past the highest number of EDIL schools were found. And as such schools tended to be community-financed, the majority of these schools were constructed from less permanent materials (Fig. 2.4).

The story for the availability of text books at school also points to significant improvements—at least initially. These improvements came on the back of a large joint Government and donor effort to ensure that at least every student had one book for maths and one book for reading. This effort was largely successful as evidenced by the data for 2012/2013, a year in which 3 million text free books were distributed, but its effects seem to be petering out. One positive aspect to note is that in Savanes, the poorest and usually most underserved region in the country the availability of textbooks is highest (Fig. 2.5).

2.3 Learning Outcomes

While success rates at the school leaver exam improved, not all students advance to a stage where they can sit for the school leaver exam. Drop-out rates remain elevated. Almost one in five children quit during or after their first year at school. Of those who remain, most make it till grade 5 (CM1) when another 10% drops out. All in all, of every 100 children starting primary school, only 70 complete it. This number is the same for boys and for girls, but there is a marked difference when they drop out. During the first year of school, boys have a bigger likelihood of dropping; in grade 5 girls are more likely to drop out (Fig. 2.6).

For those who remain in school learning assessments show a decline in performance. PASEC collects data on learning achievements for pupils in grade 2 and in grade 5 (grade 6 in 2014). Assessments were carried out in the years 1999/2000, in 2009/2010, one year after the introduction of free primary education and in 2013/2014.Footnote 4 The first assessment implemented nine years prior to the introduction of free primary education was introduced, finds that the majority of students in grade 2 and grade 5 performed satisfactory on both the French and mathematics tests. This changed in the second round implemented in 2009/2010. Now the majority of students whether in second or in fifth grade are no longer performing adequately. Only 40% of students in grade 2 perform satisfactory on the French test, and even less (29%) in grade 5. The latter is remarkable as students in grade 2 are part of large cohort of students who benefited from free primary education. Hence given the stress the arrival of large numbers of additional students in CP1 put on the education system, one might expect that for this cohort learning outcomes were lower. Indeed, evidence from e.g. Tanzania suggests that large influxes of students have a negative impact on learning achievement (Hoogeveen and Rossi 2013). What the Togo data show is that this negative impact spilled over to students in other grades, even though they started their education career prior to the introduction of free primary education. One possible explanation for this is that as a large body of new students entered the school system, classrooms and teachers initially assigned to higher grades were reassigned to CP1 to accommodate the new students. This is supported by the evolution of student to classroom ratios which increased between 2000 and 2010 from 40 to 53 for students in grade 2—is expected as this is the cohort with additional free education students, but also increased for students in grade 5: from 37 to 52 students per classroom. Another, complementary explanation is that the economic and political crisis left its mark on the quality of education in Togo’s primary schools, reducing learning across the board.

Learning wise, the education system appears not to have recovered from the shock and in 2014 student PASEC scores are more or less comparable with those from 2010. They are worse for students in grade 2 for which the fraction of students that performs satisfactory dropped even further, and compare (math) or worse (French) for students in grade 5 (Fig. 2.7).

2.4 Is Togo a Special Case?

The experience of Togo is illustrative for what happened elsewhere in low income sub-Saharan Africa (i.e. countries with per capita incomes of less $1000). Like Togo, most countries substantially increased primary school enrollment. For the 24 low-income countries in the region, net enrollment went up from 55% in 2000 to 76% in 2016 (Togo went from 51 to 89%). Despite the increase in enrollment, inequities continue to exist in Togo, by gender (90% male; 87% female), by location (96% urban; 85% rural) and particularly by wealth class (80% poorest quintile; 97% wealthiest quintile). These patterns are not dissimilar to those found elsewhere in the region.

Also, with respect to the outcomes on the learning tests does Togo not stand out relative to comparators in francophone Africa. Looking across PASEC test results for francophone countries one notes that Togo performs better than some (Chad and Niger in particular) and worse than others (Senegal, Burundi, Burkina Faso). Togo does worse in French than most francophone countries, and better in maths. In fact, Togo performs pretty much around the average score which is 42.7 for French and 41.0 for maths. Like other countries the problem of low learning achievement emerges in the early grades (Bashir et al. 2018) (Fig. 2.8).

2.5 Conclusion to the Chapter

Viewed from one perspective, Togo’s education system has been remarkably successful. During the economic and political crisis that affected the country between the mid-1990s and early 2000s, Togolese parents continued to make sure their children enrolled in primary schools, often opting for private education or resorting to community initiatives. Following the crisis, the public system recovered and navigated successfully the stresses associated with the abolishment of school fees. Its introduction starting in the 2008/2009 school year led to a rapid expansion of the primary school system, which was aptly managed. Student–teacher and student–classroom ratios increased, but only temporarily as more teachers were recruited and more classrooms constructed. Pass rates improved and the system managed to enhance its internal efficiency, reducing the fraction of students that do not pass from one grade to the next and limiting school drop out. As many more students started attending school, many—though not all, of the disparities between regions, rural and urban areas, by gender and wealth categories disappeared.

Free primary education did not come without cost and the Togolese authorities allocated substantial budgetary resources to primary education, in fact more than doubling the percent of GDP spent on primary education. Also spending per pupil increased considerably. These achievements demonstrate the commitment of Togolese parents and authorities to education.

Yet there is another perspective. Expanding access, improving attendance, enhancing efficiency and providing budgetary resources alone, is not sufficient to guarantee success. Too many children continue to drop out of school, implying individual drama and resource wastage. More importantly, evidence from learning tests suggests that the majority of primary school leavers do not master core competencies in reading, writing, and arithmetic. The results are suggestive of a profound learning crisis.

So it happened that the number of students in the public primary school system doubled from 570,000 in 2000 to over a million in 2014, and that the number of students who completed primary school went up from 100,000 in 2000 to around 200,000 in 2014. Yet, though budgets more than doubled (expressed in real terms they went up by a factor 2.35), the number of students who left primary school performing satisfactory in French increased only from 71,000 in 2000 to about 95,000 in 2014. The number of students performing satisfactory in math increased less, from about 60,000 in 2000 to 77,000 in 2014. Expressed this way, the enormous increase in spending appears to have achieved little.

Both school attendance and learning while at school are needed to assure that money invested in education yields a decent return. It is not the case now, which raises the question what could be done to rectify the situation. This question is explored in the remainder of this book.

Notes

- 1.

Of these few attended EDIL schools as this kinds of school is almost exclusively found in rural areas.

- 2.

A free-fee education policy was already established in the 1992 Constitution, but remained unimplemented. In 2000, tuition fees for girls were reduced, to encourage their enrollment, and in 2007–2008, all primary-school fees were abolished.

- 3.

Temporary teachers are in their probationary period and will either be confirmed as civil servants or dismissed. Their earnings are lower than civil servants. Assistant/volunteer teachers are individuals who do not have the necessary qualifications to be recruited as temps and therefore work as assistants in hopes of being integrated to the civil service rolls at a later date. These individuals earned less than 5000 FCFA/month ($10) in 2013.

- 4.

The “Programme d’Analyse des Systèmes Éducatifs” (PASEC, or “Programme of Analysis of Education Systems”) was launched by the Conference of Ministers of Education of French-Speaking Countries (CONFEMEN). These surveys are conducted in French-speaking countries in Sub-Saharan Africa in primary school (grade 2 and 5) for Mathematics and French. Each round includes ten countries. PASEC I occurred from 1996 to 2003; PASEC II from 2004 to 2010 and PASEC III was conducted in 2014. The PASEC assessment tools evolved over time, and the raw PASEC score are not comparable. Yet each PASEC round defines a cut-off score above which performance may be considered satisfactory. We use the percent performing satisfactory in each round to make comparisons, whereby we use the PASEC score obtained by the end-of-the year test for year when PASEC also carried out a test at the beginning of the school year.

References

Bashir, Sajitha, Marlaine Lockheed, Elizabeth Ninan, and Jee-Peng Tan. 2018. Facing Forward: Schooling for Learning in Africa. Africa Development Forum Series. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-46481260-6.

Hoogeveen, Johannes, and Mariacristina Rossi. 2013. Enrollment and Grade Attainment Following the Introduction of Free Primary Education in Tanzania. Journal of African Economies 22 (3): 375–393.

PASEC. The Analysis Programme of the CONFEMEN Education Systems (Programme d’Analyse des Systèmes Educatifs de la CONFEMEN). Various Years.

Republic of Togo. Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education. National Yearbook of School Statistics (Annuaire National des Statistiques Scolaires). Various Years.

UNESCO, UNICEF. 2014. TOGO Rapport d’état du système éducatif. Pour une scolarisation primaire universelle et une meilleure adéquation formation-emploi. Volume 1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Annex

Rights and permissions

The opinions expressed in this chapter are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The use of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank's name, and the use of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank's logo, shall be subject to a separate written license agreement between the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank and the user and is not authorized as part of this CC-IGO license. Note that the link provided above includes additional terms and conditions of the license.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hoogeveen, J., Rossi, M. (2019). Primary Education in Togo. In: Hoogeveen, J., Rossi, M. (eds) Transforming Education Outcomes in Africa. Palgrave Pivot, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12708-4_2

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12708-4_2

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Pivot, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-12707-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-12708-4

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)