Abstract

In this chapter, I examine how the decompositional split-DP analysis presented in Chap. 4 fares with Korean, a language whose N modifiers have not been much studied in a formal framework. Our examination shows that the proposed analysis captures several important aspects of N modification phenomena in Korean, yet it falls short of capturing certain adjective ordering restrictions (AORs) attested by the language. To resolve these issues, I propose an output-based filtering device within an optimality theoretic framework and show how doing so yields results that adopting a derivational approach alone cannot. In this context, I answer two outstanding questions raised in Chap. 3, namely, what governs the ordering of RCs inside the same nominal in Korean and why in Korean, occurring immediately after the distal demonstrative (DEM) ku may allow an N modifier to occur preceding a more complex N modifier in apparent violation of weight-based AORs.

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

- 1.

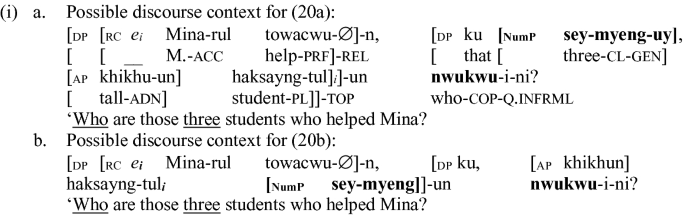

Following standard practice, I am glossing morpheme -uy which occurs on a ‘NUM + CL’ sequence as a genitive marker here. But I assume that it is actually a dummy element. Therefore, I do not represent it in the syntactic trees here and below. One reason to think that such occurrences of -uy are dummy elements is that their meaning has nothing to do with possession. Furthermore, the apparent GEN marker does not show up when the same ‘NUM + CL’ sequence occurs DP-finally, as shown in (20b). That said, to keep things manageable, I do not further discuss the status of -uy here. Instead, I refer the interested reader to An 2014, wherein it is claimed that some occurrences of -uy is a dummy agreement marker.

- 2.

I posit that the RC here is base-generated at the pre-existing [Spec, DPd/r] rather than at an adjoined position because, as stated in Chap. 4 (Sect. 4.3.3), I assume that in article-less languages, PELI is satisfied for DPd/r if a locative element (e.g., a DEM) can pronounce it within its projection, but if not, then a non-restrictive RC may pronounce it by occupying its Spec position. In the case of (14), the DP at hand contains a DEM. Therefore, the DPd/r is pronounced by the DEM, and this makes the RC adjoined to DPd/r. However, that is not the case with (16b) and hence a slightly different merge site for its RC.

- 3.

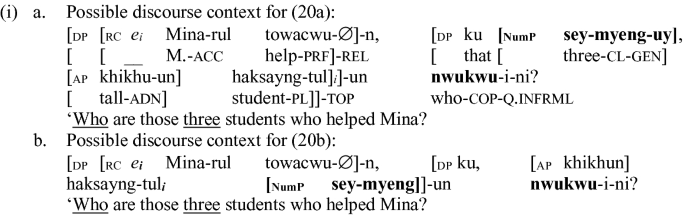

For example, they can both occur in contexts where the speaker wants to find out the names of the three students who helped Mina, as shown in (i), and since wh-questions presuppose the existence of the individuals in the denotation of the wh-constituent at hand, these DPs can be said to denote discourse-old individuals.

- 4.

In fact, sentences (20a, b) can be most naturally uttered with a focal stress on seymyeng even though they do not have to carry a contrastive-focus meaning. And according to my intuition, the presence of seymyeng in these sentences implicates that the fact that the number of students who helped Mary is three is somehow noteworthy.

- 5.

And given what is stated in Footnote 2, the RCs merge at an adjoined position here because the DP already contains a DEM, unlike the case with (16b), but resembling cases like (14).

- 6.

In answer to ‘What did you buy yesterday?’, a Korean speaker can utter (37a) but not (37b), and this shows that between the two examples, the former instantiates the more canonical constituent order.

- 7.

This was noted by an anonymous reviewer, who raised the possibility that the grammaticality or ungrammaticality of data containing RCs may be impacted by what type of gap the RCs contain.

- 8.

- 9.

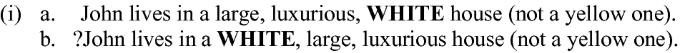

An anonymous reviewer claims that this constraint is contradicted by the existence of English data like (i), in which a more nominal AP occurs farther away from the head N than a less nominal one does.

(i) a gold musical box.

What is important to note, however, is that every OT constraint is violable and every language is assumed to have potentially different constraint rankings. To apply this to the data at hand: in (i), musical forms a compound N with box and gold modifies the entire compound N, resembling the structure of the Korean example given in (3a), i.e., say mohyeng catongcha ‘a new miniature car’. Given this, on the present analysis, musical would merge at [Spec, \(\surd{\text{P}}\)] and gold would merge at [Spec, nP] and between musical and gold, the latter has a more relative semantics (i.e., a gold musical box need not be (purely) gold). Therefore, the surface order in which they occur would satisfy RelLft even though it may violate *NA > NNA. If correct, then, the present analysis suggests that English has a different constraint ranking than Korean but that is expected under an OT-based analysis. I should also point out that, in lieu of musical, music can occur in (i) (i.e., a music box), as numerous Google searches I have conducted validate, and in such cases, neither RelLft nor *NA > NNA would be violated. I therefore conclude that the existence of data like (i) does not undermine the analysis put forward here.

- 10.

Here and below, I only provide partial tableaux to stay focused on the issues at hand. For instance, the data in (63)–(64) all vacuously satisfy DegLft, so this constraint is omitted in tableaux (65)–(67).

- 11.

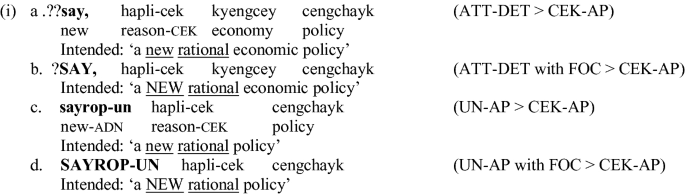

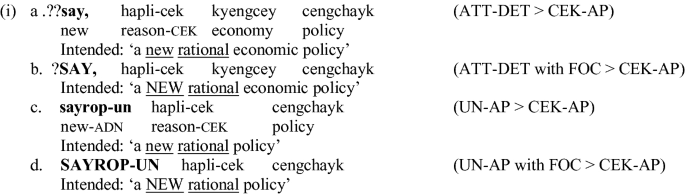

Essentially the same reasoning explains why sayropun ‘new’ would be preferred over say ‘new’ in certain contexts, as shown in (i): sayropun is a tri-syllabic AP whereas say is just mono-syllabic. For this reason, when they occur preceding a CEK-AP, sayropun (almost) always occurs instead of say. And under the present analysis, this is expected because while (ia) and (ib) do not comply with HvyLft (the first example incurs two violations and the second one incurs one violation of this constraint), the (c) and the (d) examples do. Note that with regard to the other constraints, they are at a tie since they (vacuously) satisfy them.

- 12.

Essentially the same logic explains the goodness of (10), which exemplifies that a FOC on the thematic AP may allow it to occur preceding a CEK-AP .

- 13.

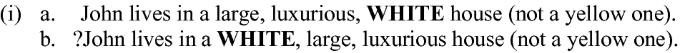

I thank an anonymous reviewer for drawing this to my attention, that is, the fact that not all focused ADJs in Korean need to occur in the left-periphery of a DP. Notably, this is also true of other languages. For example, in English too, placing a focal stress on an ADJ alone can indicate focus-marking and therefore a FOC-marked ADJ need not appear at the left-periphery of the DP although it can, as shown in (i); in fact, (ib) is judged less good than (ia), paralleling the behavior of the Korean data given in (73)–(74).

- 14.

See Kim 2016a and the references there regarding the semantics of -te that occurs as part of an RC marker and its contribution to bringing about such a speaker-oriented recollective meaning.

- 15.

One may wish to challenge this explanation by claiming that the speaker meeting the person under discussion describes a more familiar experience to her than her merely hearing Mina mention him; that is, (45a), which instantiates the ‘RC1 > RC2’ order, violates FmlRcLft. But one cannot deny that the event of Mina mentioning that person to S is what S directly experienced. Therefore, I conclude that both examples in (45) satisfy FmlRcLft, which makes PreRcLft the deciding constraint in this case.

- 16.

Interestingly, Korean lacks specific but indefinite DEMs which would correspond to the occurrences of this and that in data like (110). In the literature, English DEMs which occur in contexts like (110) have been characterized as performing an ‘affective’ function [a term due to Liberman (2008)] (see, e.g., Potts and Schwarz 2010; Acton and Potts 2014 ; and the references there) . According to Potts and Schwarz (2010: 2), English speakers use DEMs affectively to “foster a sense of closeness and shared sentiment” with other discourse participants and such a pragmatic function is most likely a universal property of DEMs. Given this, the fact that Korean DEMs do not perform the same function as the English DEMs in (110) raises an interesting question of why that might be the case. I take up this question in Chap. 6.

- 17.

Without the RC, the N mokkeri in (117a) will be construed as referring to some or any non-specific necklace (i.e., ‘a necklace’) though in some contexts (e.g., if some necklace has already been introduced to the discourse) , it may be construed as referring to some specific/definite necklace (i.e., ‘the necklace’).

- 18.

Note that sentence (123b) can be felicitously uttered in a context where there are multiple individuals who bear the name Chelswu but that is not the intended context here, as indicated in the context for (123).

- 19.

(126b) can be judged acceptable if it is construed as denoting ‘the expensive necklace that Mina bought and brought, that is, if it is interpreted as simply referring to—without the emotive connotation—some discourse prominent necklace about which the fact that it is expensive and it was bought and brought by Mina has been established in the discourse context.

- 20.

The data in (129)–(130) may all sound grammatical if they are just read out loud because some of the free-standing occurrences of ku can be construed as the ordinary DEM ku, but as indicated in the English translations, each occurrence of ku here is meant to modify the property that is denoted by the AP that it co-occurs with.

- 21.

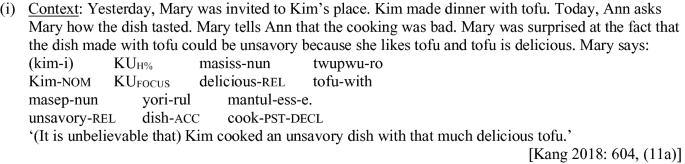

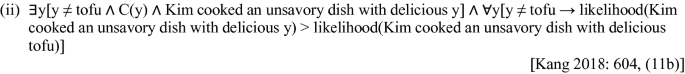

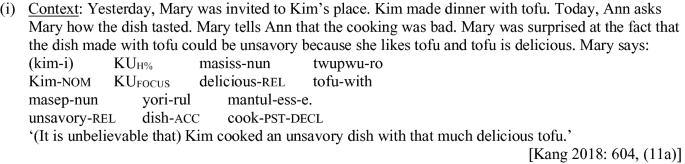

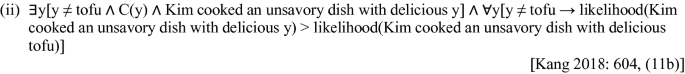

At the final stage of writing this book, I came to learn that Kang (2018) makes similar observations about certain occurrences of the distal DEM ku in Korean and claims that such occurrences of ku are best analyzed as a scalar , additive focus modifier which is comparable to English even. To illustrate this, she discusses how the presence of ku in data like (i) encodes the speaker’s unexpected surprise, and offers (ii) as the meaning of ku in (i), where C represents a contextually constructed subset of alternatives.

However, Kang mainly discusses the occurrence of ku in exclamative contexts and how it encodes mirativity in the sense of DeLancey (1997) . Furthermore, as far as I can see, the occurrences of KU we are concerned with here have nothing to do with additivity nor do they evoke alternatives and then rank them on a scale, which is what a scalar focus modifier would do (see, a.o., Traugott 2006 and the references therein). To take (126a) in the text for example, by uttering it, the speaker does not implicate that there are other (expensive) items that Mina bought and brought for her and the necklace at issue is the least likely one that Mina was expected to buy and bring for her. In fact, such an implicature is impossible to draw for this datum.

Given this, while I do see that the data that Kang discusses are bound to receive mirative interpretations, and I also agree with her that the meaning of non-physically deictic , non-anaphoric, and seemingly emphatically used ku has something to do with a scale, I believe that her analysis and mine are rather different in nature and scope although future research may show that a uniform analysis is possible for the occurrences of ku that she talks about and those that I do here.

Moreover, I suspect that the pragmatic effects that kang talks about may arise not (just) because of the presence of the DEM in the sentences but because of the contrastive meaning that is literally conveyed by the sentences themselves, i.e., the mismatch between the speaker’s expectations about some state of affairs and their actual realizations. For instance, in (i) above, the speaker expects any dish with tofu to be delicious but the dish that Kim cooked was not, and hence the surprise on her part.

- 22.

In Chap. 6, I revisit the semantics of DEMs and dissect their features. Under the more detailed analysis offered there, what I refer to as [+STS distant] will be comprised of two different features. But for now, what we have here will suffice.

- 23.

In Chap. 6 (Sect. 6.5), I take up the question of whether Korean has “truly” supplementary RCs or not, and I show that what we call Sppl-RCs here are actually not prototypical Sppl-RCs when compared to English Sppl-RCs such as those presented in Chap. 4. That said, treating the RCs in data like (136) as Sppl-RCs for the time being will not change things for us. Hence, for referential convenience, I will keep using this label, deferring a more refined analysis of Korean RCs until later.

- 24.

The RC here is a non-restrictive RC rather than a supplementary one because it essentially repeats what is conveyed by the preceding sentence rather than adding anything new to the discourse .

- 25.

My intuition about (107a) is that it can be interpreted in such a way that ku indicates that the DP it modifies has some salient discourse-old property and the content of that property is spelled out by the N modifier that immediately follows it, i.e., the RC in this case. But further investigation will be necessary to fully articulate the semantic intuition I have about such data. Hence, I defer doing so to another occasion. See Kim 2018 for a tentative account, under which the role of the RC in such contexts is comparable to the role of an actual demonstration that is required to license DEMs in English, as pointed out by Kaplan (1977/1989).

References

Acton, Eric K., and Christopher Potts. 2014. That straight talk: Sarah Palin and the sociolinguistics of demonstratives. Journal of Sociolinguistics 18 (1): 3–31.

An, Duk-Ho. 2014. Genitive case in Korean and its implications for noun phrase structure. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 23 (4): 361–392.

Belletti, Andriana. 2004. Aspects of the low IP. In The structure of CP and IP: The cartography of syntactic structures, vol. 2, ed. Luigi Rizzi, 16–51. New York: Oxford University Press.

Bolinger, Dwight. 1967. Adjectives in English: Attribution and predication. Lingua 18: 1–34.

Bouchard, Denis. 2002. Adjectives, number and interfaces: Why languages vary? Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Choi, Hye-Won. 1996. Optimizing structure in context: Scrambling and information structure. Stanford, CA: Stanford University dissertation.

Chou, Chao-Ting Tim. 2012. Syntax-pragmatics interface: Mandarin Chinese why-the-hell and point-of-view operator. Syntax 15 (1): 1–24.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2005. Deriving Greenberg’s Universal 20 and its exceptions. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 315–332.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2010. The syntax of adjectives. A comparative study. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo, and Luigi Rizzi. 2008. The cartography of syntactic structures. In CISCL working papers on language and cognition, vol. 2, ed. Vincenzo Moscati, 43–59. University of Siena.

DeLancey, Scott. 1997. The mirative and evidentiality. Journal of Pragmatics 3: 371–384.

Grimshaw, Jane. 2001. Economy of structure in OT. Rutgers Optimality Archive 434.

Gunlogson, Christine. 2001. True to form: Rising and falling declaratives as questions in English. Santa Cruz, CA: University of California-Santa Cruz dissertation.

Huddleston, Rodney, and Geoffrey Pullum. 2005. A student’s introduction to English grammar. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Iida, Masayo, and Peter Sells. 1988. Discourse factors in the binding of zibun. In Papers from the second international workshop on Japanese syntax, ed. William J. Poser, 23–46. Stanford, CA: CSLI.

Kang, Arum. 2018. Unexpected effect: The emphatic determiner with gradable NPs in Korean. The Journal of Studies in Language 33 (4): 595–615.

Kang, Soon Haeng. 2005. On the adjectives in Korean. In University of Venice working papers in linguistics, vol. 15, 153–169.

Kang, Soon Haeng. 2006. The two forms of the adjective in Korean. In University of Venice working papers in linguistics , vol. 16, 137–163.

Kaplan, David. 1977. Demonstratives: An essay on the semantics, logic, metaphysics, and epistemology of demonstratives and other indexicals. Ms., published in Themes from Kaplan. 1989. ed. Almog, Joseph, John Perry, and Howard Wettstein, 481–564. New York: Oxford University Press.

Keller, Frank. 2000. Gradience in grammar: Experimental and computational aspects of degrees of grammaticality. Edinburgh, UK: University of Edinburgh dissertation.

Kim, Jaieun. 2013. Subject and point-of-view in Korean: The syntax-discourse interface. Seoul, Korea: Sogang University master’s thesis.

Kim, Min-Joo. 2016a. The ‘imperfective’ in attributive clauses in Korean as a window into the evidential past and the metaphysical future. Studies in Language 40 (2): 340–379.

Kim, Min-Joo. 2016b. Cognitive indexical usage of demonstrative ku in Korean and a split DP analysis. In Proceedings of the 18th Seoul international conference on generative grammar, ed. Kim, Tae Sik, and Seungwan Ha, 175–194. Seoul: The Korean Generative Grammar Circle.

Kim, Min-Joo. 2018. What does a demonstrative do when it co-occurs with a relative clause and an adjective phrase in Korean? Paper presented at Semantics 2018: Looking Ahead. University of Massachusetts-Amherst, March 10, 2018.

Larson, Richard K. 1998. Events and modification in nominals. In Proceedings from semantics and linguistic theory (SALT) VIII, 145–168. Cornell University Press.

Larson, Richard K. 2000. Temporal modification in nominals. Paper presented at the International Roundtable on the Syntax of Tense. University of Paris VII, France.

Larson, Richard K., and Naoko Takahashi. 2007. Order and interpretation in prenominal relative Clauses. In Proceedings of the workshop on altaic formal linguistics II. MIT working papers in linguistics, vol. 54, 101–120. Cambridge, MA: MITWPL.

Liberman, Mark. 2008. Affective demonstratives. Language Log, http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=674. Accessed 28 Mar 2018.

Minkoff, Seth. 1994. How some so-called “thematic roles’’ that select animate arguments are generated, and how these roles inform binding and control. Cambridge, MA: MIT dissertation.

Minkoff, Seth. 2004. Consciousness, backward coreference, logophoricity. Linguistic Inquiry 34 (3): 485–494.

Potts, Christopher. 2005. The logic of conventional implicatures. New York: Oxford University Press. (2003 University of California-Santa Cruz dissertation.)

Potts, Christopher, and Florian Schwarz. 2010. Affective ‘this’. Linguistic Issues in Language Technology 5: 1–29.

Prince, Alan, and Paul Smolensky. 1993. Optimality theory: Constraint interaction in generative grammar. Rutgers University Center for Cognitive Science Technical Report 2.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Sato, Yosuke, and Maki Kishida. 2009. Psychological predicates and the point-of-view hyperprojection. Gengo Kenkyu [Language Research] 135: 123–150.

Sells, Peter. 1987. Aspects of logophoricity. Linguistic Inquiry 18 (3): 445–479.

Sorace, Antonella, and Frank Keller. 2005. Gradience in linguistic data. Lingua 115 (11): 1497–1524.

Speas, Peggy, and Carol Tenny. 2003. Configurational properties of point of view roles. In Asymmetry in grammar, ed. Anna Maria Di Sciullo, 315–344. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Sproat, Richard, and Chinlin Shih. 1988. Prenominal adjectival ordering in English and Mandarin. In Proceedings of NELS, vol. 18, 465–489. Amherst, MA: GLSA.

Sproat, Richard, and Chinlin Shih. 1990. The cross-linguistics distribution of adjectival ordering restrictions. In Interdisciplinary approaches to language: Essays in honor of S-Y. Kuroda, ed. Georgopoulos, Carol, and Roberta Ishihara, 565–593. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Stirling, Lesley. 2005. Switch-reference and discourse representation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Tenny, Carol L. 2006. Evidentiality, experiencers, and the syntax of sentience in Japanese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 15: 245–288.

Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 2006. The semantic development of scalar focus modifiers. In The handbook of the history of English, ed. van Kemenade, Ans, and Bettelou Los, 335–359. Malden, MA: Basil Blackwell.

Zribi-Hertz, Anne. 1989. Anaphor binding and narrative point of view: English reflexive pronouns in sentence and discourse. Language 65 (4): 695–727.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Kim, MJ. (2019). Capturing the Korean Facts. In: The Syntax and Semantics of Noun Modifiers and the Theory of Universal Grammar. Studies in Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, vol 96. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05886-9_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05886-9_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-05884-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-05886-9

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)