Abstract

This chapter seeks to answer the question of how resource differentiation influences the forms and aims of migrant engagement, that is, the political participation of recent migrants in Switzerland. More-fluid patterns of mobility highlight the need to observe different approaches to residents’ civic engagement, which are not restricted to the practices of full citizens. We expand the outlook on what counts as a political activity by including acts such as participating in petitions, demonstrations and consumer boycotts. Although these activities are largely no longer considered unconventional, they are usually not considered in research on migrants’ political involvement. Based on an analysis of varied political activities open to any resident of the state, the paper delivers new insights into migrants’ engagement linked to different resources and forms of capital. Previous works have confirmed the influence education provides on political participation of migrant and ethnic minorities. Our results show that higher level of education increases the chances of acting in non-conventional activities, but does not play a role for acting in the representative political sphere. It is rather the time spent in Switzerland and local language skills which matter most for acting in political organizations. By adding migration-specific factors, this paper makes a further contribution to debates on what counts as a political resource. Experiences of international mobility provide the necessary social esteem for migrants to act in non-regulated activities which allow for individualized and direct forms of expression. New, selective and temporary mobility therefore broaden political action repertoires.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

New, increasingly selective and temporary patterns of migration pose a challenge to social inclusion and migrant engagement. On the one hand, the temporary character of residing brings about different expectations from migrants and affects migrants’ relationship with the environment they live in. It occasions questions about whether people who are often on the move develop different means of engaging and making sense of their belonging.

On the other hand, selective migration regimes in many developed countries lead to new residents being better educated than ever before (OECD/UNDESA 2013), which again has implications for migrants’ ability to act. This chapter focusses on migrants’ political engagement and links it with migrants’ resources. After Van Hear (2014) proposed renewing attention on the part class plays in migration, we argue that resources and various sources of capital play an important role in political engagement of migrants. Because different groups control different volumes and compositions of capital and different forms of engagement require different forms of capital, we hypothesize that migrants’ skill levels influence forms and aims of migrant engagement. Access to the political sphere can be gained by using skills to engage with the local environment and by using resources such as networks of organizations in which people are embedded. Although other forms of social difference, such as ethnicity, gender, generation or religion (de Rooij 2012; Giugni et al. 2014; Van Tubergen and Kalmijn 2005), have been emphasized as important factors in explaining migrants’ mobilization, this chapter also calls for considering migrants’ resource levels in the context of migration experience another key factor. The main research question is how does migrant-specific socio-economic differentiation influence forms of migrant engagement?

Research on migrants’ incorporation into the host society and transnational activities has mostly focussed on political integration predominantly related to electoral practices (for instance, Morawska 2009; Eggert and Giugni 2010). More-fluid patterns of mobility call attention to the need to observe residents’ different approaches to engagement with the host country, which are not restricted to the practices of full citizens of the state. In addition to “conventional” political activities, such as voting in elections or involvement in political parties, Barnes and Kaase (1979) highlight the importance of more “unconventional” political activities, such as participating in petitions, demonstrations and consumer boycotts. Although these activities are largely no longer considered unconventional, they are not usually considered in research on migrants’ political involvement (Però and Solomon 2010, p. 8).

This research relies on the exploration of political practices of recently arrived migrants to Switzerland. The Migration-Mobility Survey includes a module that focusses on the civic engagement and political and social participation of migrants in Switzerland and their countries of origin. Questions are specifically designed to include forms of engagement that are open to any resident of the state. We devote Sect. 10.2 of the chapter to emphasizing the need for a research approach that employs a broader understanding of engagement. This approach is specifically relevant for the study of migrant political engagement because targets and agencies of engagement relate to their political socialization and experiences of moving internationally. In addition, although migrants are not necessarily eager to gain access to the representative political sphere, they might participate in other areas of engagement (Sect. 10.3). Section 10.4 introduces the concept of “resource environment” in the context of political participation. We combine migrants’ levels of individual resources with migration background and experiences of migration to explain political mobilization. We assess the effect of the various elements of the resource environment on forms of political participation by means of logistic regression (Sect. 10.6). Finally, in Sect. 10.7, we discuss our findings and identify the limitations of our approach.

2 Understanding Immigrants and Political Participation

Political participation is a principle of democracy. Such participation has been defined as “voluntary activities by ordinary people directed towards influencing directly or indirectly political outcomes at various levels of the political system” (Verba et al. 1995, pp. 38–39). The debates about political participation usually revolve around questions concerning who can legitimately make claims on the system. The growing presence of foreign residents makes the issue of political participation particularly complex. With political rights attached to citizenship, foreigners are largely excluded from the official participatory process, although they remain affected by the outcomes of political decisions in all areas of their daily lives. Switzerland has one of the highest proportions of non-citizen residents among nations counting more than five million inhabitants; in 2016, 24.6% of permanent residents in Switzerland did not have Swiss citizenship (Swiss Federal Statistical Office 2017). In a situation in which one-quarter of the residents are not allowed to participate in federal elections and have few other opportunities to participate politically, several questions pertaining to the quality of democratic representation come to mind: Not being able to vote, are foreign residents making claims towards the political system in other forms? Are they interested in the Swiss political system at all? These questions are relevant because society should have an interest in promoting mutual understanding and striving towards social cohesion.

In parallel with having a growing presence of residents with limited opportunities to influence the political system through conventional channels, Switzerland has, in the last decade, experienced increased anti-immigration rhetoric. In addition, although political rights of non-citizens are restricted by their official political membership status, this restriction does not prevent accusations being made against migrants that they are refusing to become involved in local societies. When civic engagement of recent migrants features in public debates, the topic is usually the alleged lack of interest from the migrants in contributing to civil society. Headlines in some popular German-speaking newspapers indicate the controversy: “How many Germans can Switzerland tolerate?”Footnote 1 (Rüttimann 2007 in the Blick), “The elite is not integrated”Footnote 2 (Schaffner 2012 in the Tagesanzeiger), and “A foreigner problem of a different kind”Footnote 3 (Gerny 2012 in the NZZ). This backlash against immigrants is not reserved for low-skilled migrants who are often – also in other European countries and the United States – perceived by natives as less willing to work hard and as dependent upon scarce national resources (Larsen 2011; Senik et al. 2009). Instead of placing a burden on local resources, media and politicians alike are calling on migrants to contribute to civil society (Phillimore et al. 2018). In Switzerland, it is not uncommon to hear complaints about high-skilled migrants living in “parallel societies” or “expat bubbles” (Fournier 2012; Schneider-Sliwa 2013). In an interview from 2012 for the magazine Die Zeit, the former justice minister Simonetta Sommaruga spoke specifically of “too many high-skilled migrants who hardly speak any German. They are not integrated, and they cultivate this” (Daum and Teuwsen 2012). Responses from the migrants to persistent demands for integration vary from justifying their position with arguments of time constraints (Dacey 2012) of the short durations of their stays to noting the fallacy of these accusations (Oppliger 2013). The expansion of self-help and community groups and an increase in demand for volunteering opportunities in urban areas speak against the image of non-interested foreigners. Is it possible that the perception of migrants’ political apathy is due to not focussing attention on the forms of participation in which migrants do engage?

Because migrants in the prevailing discourse are considered from the perspective of nation states, either of home countries or of receiving countries, most studies observe migrants as objects of political interventions rather than consider them political agents. In addition, when migrants’ activities are the subject of inquiry, the usual understanding of political engagement as being limited to electoral practices (Eggert and Giugni 2010; Morawska 2009) obscures political initiatives that occur in other public spheres. The general literature on citizens’ political engagement suggests that the nature of political participation is changing in terms of channels, topics and targets (Giddens 2002; Norris 2002; O’Toole and Gale 2013). Social transformations at the global level have led to “new grammars of actions” (McDonald 2006) that are closer to everyday and lifestyle forms of activism. Some of the major driving forces behind “detraditionalization” (Giddens 2002) and the general citizen disengagement from conventional politics surrounding political parties have been located in social events such as the end of the Cold War and the development of new technologies. The Cold War had a destructive effect on the image of political authorities and on the mobilizing potential of political parties (Beck 1997). Contemporary forms of action that are more individualized and self-reflexive draw upon new technologies that allow for a global outlook and for a different perception of what matters in the world and at the same time enable a more creative repertoire of action (O’Toole and Gale 2013). Forms of action that are based on the “life politics” (Giddens 2002) of personal and self-reflexive engagement with the world are manifested in actions of political shopping, consumer boycotts, e-activism and veganism, to name a few. In addition to the conventional and unconventional forms of political participation, researchers characterize such forms as “post-conventional” (Stolle and Hooghe 2005). Bang (2004) sees participants engaging in such forms of participation as preferring to engage in concrete, local, self-actualizing political projects rather than participating in formally organized programmes with political ideologies. Political consumerism, for example, is supposed to appeal to people who view themselves as alienated from formal political settings (Micheletti 2004). Considering that the literature on citizens’ political participation acknowledges a turn and diversification of political action, it is surprising that “unconventional” or “post-conventional” forms of participation are rarely discussed in the research on migrants’ involvement. With an exploration of “truly” transnational political practices of migrants in the Netherlands, van Bochove (2012) provides a rare example of recognizing migrants as political agents beyond the conventional forms of engagement and beyond protests or illegal acts of resistance.

The dominant literature on migrant political engagement uses the approach of political opportunity structure (POS), which stays close to its original objective of explaining migrants’ collective actions in either ethnic or cross-ethnic organizations (Koopmans et al. 2005; Koopmans and Statham 1999). This approach hardly considers the above-mentioned new patterns of political action, which are found to be more individualized, direct and expressive (O’Toole and Gale 2013). In Sect. 10.3, we explain how our empirical investigation tries to address the mentioned limitations.

3 Research Approach for Broader Understanding of Engagement

The data used for this study derive from the newly conducted Migration-Mobility Survey, which focusses on several aspects of migrants’ living conditions in Switzerland (see Chap. 2). The survey includes a module on civic engagement and political and social participation of migrants in Switzerland and in their countries of origin. Questions were specifically designed to include forms of engagement that are open to any resident of the state. To be included in the survey, one had to have been born outside of Switzerland, to not hold a Swiss nationality and to have immigrated to Switzerland within the past 10 years. Based on these requirements, the respondents of the survey stay in Switzerland based on holding one of the following permits: short-term (up to 1 year), resident (1 or 5 years), settlement or diplomat status. Thus, our target population is not entitled to vote in general elections in Switzerland. Except for voting at the cantonal level in two cantons (Jura and Neuchatel) and at the communal level in communes in five cantons (Jura, Neuchatel, Vaud, Freiburg and Geneva) (EKM 2018), non-citizens are largely also excluded from voting at the local level. This situation makes it particularly compelling to accept a broad definition of political participation in an attempt to cover the previously mentioned description of voluntary activities directed towards influencing political outcomes by Verba et al. (1995).

Survey respondents were asked to identify from among the mentioned activities (see Table 10.1) those they did in the last 12 months with the objective of improving things or of helping to prevent things from going wrong.

The responses include activities surrounding the established political entities that are open to non-citizens. They can make claims towards formal representative politics, try to influence political terrain by supporting certain political ideologies or even by joining a political party. Responding to accounts of general disengagement from party politics since the 1990s and given that party politics is likely to be even more inaccessible to migrants, the list includes other activities that might be targeting a wider range of institutions beyond the government and that also do not require delegates and representatives to act in the name of others. McDonald (2006) writes about global social movements in which activists are reluctant to submerge their identity into any organization or movement and rather engage in actions that are more expressive, hands-on and aim for direct effects. People can choose to express their alignments by joining a single cause, with ad hoc involvement relating to a specific issue or goal. They might join a demonstration, show alliance with a specific cause by displaying visual statements on their clothing or only add a campaign badge to a social media picture. These forms show political actions as closer to everyday and lifestyle decisions. Our approach, however, does not allow us to observe the motivations behind actions and stays within the investigation of forms of engagement.

In addition to exploring whether migrants do engage in these new patterns of political action, we are further interested in the attributes that distinguish the politically active in different forms of political engagement. For that purpose, we have created three major groups of activities based on the list of nine possible answers to the above-mentioned survey question (see Table 10.1), namely (a) contacting, (b) expressive and (c) quiet forms of activity. The rationale for dividing activities in these three groups is based on the typology developed by Schulz and Bailer (2012). Contacting activities include contacting a politician, government or local government official; making a donation to a political campaign or to a political party; and working in a political party or in another organization or association. We consider the following activities expressive forms: wearing a campaign badge or sticker, participating in a lawful public demonstration or using the internet to express opinions. Signing a petition or boycotting certain products is grouped together under quiet forms of activities. We acknowledge that most of these activities can be performed with various intensities and time effort. However, some forms of activities are found to be less demanding that the others. De Rooij (2012) considers signing a petition, wearing a political badge or boycotting products low-cost acts, whereas contacting activities and demonstrations fall within high-cost acts. However, our approach does not allow us to make such clear-cut distinctions because we do not have information on how often people engage in any of the activities or on how intensely they prepared for any of the acts.

4 Political Resource Environment for Migrants

Along with expanding our understanding of political engagement by examining a wider range of repertoires, this chapter also aims to contribute to the question of migrants’ resource environment. We try to identify resources that are conducive to activities of migrants. Although we align with arguments of shifting patterns of political behaviour, we accept that it is important to consider the political and social context within which this behaviour is or is not happening. The POS approach, which predominates in studying different aspect of migrants’ integration, postulates that national and local institutional frameworks with their policy setups shape migrants’ behaviour by either stimulating or inhibiting their mobilization (Fennema and Tillie 2004; Ireland 1994; Koopmans et al. 2005). Ireland (1994), as the first to apply this approach in the field of migration studies, actually compared France to Switzerland and established Swiss closed political opportunity structures as the main reason for the low level of political mobilization among migrants. Many studies, globally and in Switzerland, have followed the trend of investigating institutional environments and their role in migrants’ actions (Eggert and Giugni 2010; Giugni et al. 2014; Giugni and Passy 2004; Manatschal and Stadelmann-Steffen 2014).

Nevertheless, Però (2008) considers a focus on political opportunity structures insufficient to explain migrants’ political behaviour. In his account of Latin American mobilization in London, Però gives credit to the approach and confirms the importance of opportunity structures of the receiving country for channelling the Latino collective action. The limitations of the approach are found largely in terms of its narrow application of the institutional framework, failure to include a transnational dimension of opportunity structures and migrants’ earlier political socialization. Recent studies in the case of Switzerland have improved on the first aspect. Giugni and Passy (2004) and Manatschal and Stadelmann-Steffen (2014) assume integration policy regimes to be more than only legal regulations. Manatschal (2012) has previously shown that cantonal integration policies correspond to local cultural notions of belonging. However, in her work, the notions of who belongs to specific communities and cultural understandings of migrants’ entitlements are conceived as being expressed through integration policies. Wider cultural attitudes, such as “multiculturalism” in the United Kingdom (Però 2008) or a more migrant-welcoming culture in some Swiss cantons (Manatschal 2012), can also work towards encouraging mobilization through constituting incentives in different areas of daily life. The second main limitation of the POS approach, as viewed by Però, is that it adopts the perspective of the nation states as key referents and thus does not explain diverse and changing mobilizations within a stable institutional environment of a single country. Recent works on the interaction between migrant integration and transnationalism (Erdal 2013; Erdal and Oeppen 2013; Van Meeteren 2012) have at least partly addressed the concerns about the POS approach not being adapted to the transnational turn in migration studies. Most studies, however, stay with studying bi-national activities that bind migrants across their countries of settlement and countries of origin and do not allow for considering the rise of transnational and global political structures that are increasingly the targets of political actions (O’Toole and Gale 2013).

Considering these limitations of the predominant approach to the study of migrants’ political mobilization, we are interested in adding to the discussions by expanding the concept of a “resource environment” (Levitt et al. 2017) and adapting it to the context of political participation. We initially want to observe how the new migrants mobilize and how the “resource environment” in which individuals are embedded influences their repertoires of actions. Similar to migration itself, migrant engagement depends upon the resources that individuals or groups of people are able to mobilize. We suggest that the individual’s resource environment comprises a combination of the individual’s social and human capital, migrants’ background in terms of political socialization, their experiences in the receiving context and of cultural notions of belonging that are prevalent in resident societies. By combining all of these factors as the resource environment, we are able to analyse not only the role of the environment in structuring opportunities and obstacles for migrants but also the role of migrants’ agency. Different individuals control different compositions of capital, which influences their social position in the receiving society and their abilities as actors. The literature on political participation in general and the literature focussing on migrant political participation in particular corroborate the importance of education as a critical resource for political participation (Eggert and Giugni 2010; Koopmans et al. 2005; Morales and Giugni 2011). Migrants’ social esteem needed to engage in political activities can also come from their political biographies and from being socialized in political cultures that praise taking action. People with earlier experiences of engaging are expected to be more inclined towards recurrent mobilization in the receiving country. Political socialization starts at a young age, when people develop their political values and beliefs in interactions with the family, school, media and other agents of socialization (de Rooij 2012). We are not saying that people who were not active before migration would remain politically inactive in a new setting; rather, we postulate that experiences of migration could motivate some people to adopt new roles. The cause could be unfair working conditions, as in the case of many Latino migrants in London (Però 2008), which pushed them to organize, or assuming a new role as an accompanying spouse with more time for public involvement (Fechter 2016; Isaakyan and Triandafyllidou 2014; Trundle 2014). Finally, the possibilities to use individual resources nonetheless depend upon differential opportunities that are linked to cultural notions of belonging and to the attached predispositions for considering migrants’ rights and obligations.

5 Research Design and Methodology

In Sect. 10.3, we have already described the dependent variable (overall political participation, direct contact activities, expressive and quiet forms of activities). Because the outcome variables are binary, the models used for analysis are binary logistic regression models calculating the probability of the outcome. All of the results presented in this paper are based on data weighted with normalized weights. In this section, we describe our main independent variables, which respond to the attempt to expand the concept of “resource environment” as described above. Independent variables can be divided into three groups.

The aspect of including a transnational lens and migrants’ previous political experiences is addressed by the variables related to migration background. We introduced a new variable for democracy level in the country of birth, created based on the dataset in the Polity IV Project, Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2016. We used the variable that refers to the competitiveness of participation (PARCOMP) and captures “the extent to which alternative preferences for policy and leadership can be pursued in the political arena” (Marshall et al. 2017, p. 26). Countries are assessed each year on a scale of repressed, suppressed, factional, transitional and competitive. Because of yearly variations, we examined the average score of migrants’ countries of birth for the last 5 years, that is, from 2011 to 2016. The variable of birth country is therefore not used to examine the relevance of ethnicity as a determining factor of migrants’ engagement but rather as a proxy for migrants’ political socialization in systems with varying degrees of participation competitiveness. Countries of birth are grouped into five categories of a scale from repressed to competitive, following the classification of the Polity IV Project. Although we agree that ethnicity itself is not a mobilizing factor as such, being politically educated and socialized within a more or less politically encouraging system can play a role in migrants’ social esteem needed for participation. Given that the Swiss political system is ranked as competitive, we could also expect that immigrants from other countries with a competitive system will have higher rates of participation because of the similarities between political systems, as has been suggested by Lien (2004) and Bilodeau (2008). We add the number of times people have moved internationally and their duration of stay in Switzerland as two other variables covering migration background. We find it interesting to explore whether people who are often on the move develop different approaches to engaging and making sense of their belonging. Time since moving to Switzerland is expected to be related to political engagement because people had the possibility of expanding their networks and learning about particularistic political interests in their surroundings. Other studies have found a link between rootedness and immigrant volunteering (Manatschal and Stadelmann-Steffen 2014; Stadelmann-Steffen and Freitag 2011) and a strong link between the time spent in a new country of residence and patterns of immigrant political engagement (de Rooij 2012).

The second set of variables relates to specific migration experiences in the receiving context. Individual experiences of migration are wide-ranging, and although some migrants suffer significantly from loss of resources, others benefit more from the move. We included variables that examine the general satisfaction with moving to Switzerland, the feeling of discrimination and the level of interest in current events in Switzerland among respondents. The variable on discrimination indicates whether the respondent has experienced a situation in which she felt treated less favourably than other people were. Although the dataset includes information concerning on what basis the discrimination occurred (race, religion, immigrant background, gender, disability, age or sexual orientation), we prefer to use the overall feeling of discrimination. We believe that the experience of marginalization can work as a motivating factor to change the situation regardless of the assigned characteristics based on which people felt discriminated against. Latin migrants in London spoke of exploitation in the workplace as a push for their mobilization (Però 2008). In that sense, structural constraints rather than opportunity structures mobilized the migrants. However, if the feeling of marginalization were not accompanied by other elements of the resource environment, it might also have a discouraging effect. We can easily think of examples of discrimination leading to social exclusion of groups of migrants (Negi 2013; Wray-Lake et al. 2008). Latino labourers in the informal market in the United States face discrimination with social isolation (Negi 2013), and Arab-American immigrants (Wray-Lake et al. 2008) are shown as doubting their role in society due to experiencing prejudice based on their identity. Riaño (2003) showed how skilled Latin American women face de-qualification and de-emancipation after they have moved to Switzerland. Experiences of discrimination can therefore equally inhibit or foster civic engagement. We also account for political interest in current events in the country of residence and predict that it will positively influence political participation in general as was found in Nguyen Long (2016) and Giugni et al. (2014).

At the contextual level, we add the variable on the language region. It has been previously proven that dividing respondents according to the language spoken in the place of residence can help explain volunteering in Switzerland (Stadelmann-Steffen and Freitag 2011). The rationale for including a variable on language region in the analysis is based on different regional notions of belonging that work their approaches to inclusion and exclusion through cantonal integration policies and reveal themselves in other aspects of daily life (Manatschal and Stadelmann-Steffen 2014). The division of the variable into German-, French- and Italian-speaking regions is based on the postal code of the respondent’s residence.

Demographic and social-economic variables are included as control variables. Age, gender, level of education, level of employment, language proficiency and region of origin have been viewed in previous research as important predictors of immigrants’ voluntary engagement and political participation (Aleksynska 2008; Eggert and Giugni 2010; Giugni et al. 2014; Koopmans et al. 2005; Morales and Giugni 2011; Verba et al. 1995). The literature on political participation in general and the literature focussing on migrant political participation in particular corroborate the importance of education as a critical resource for political participation. Research specifically addressing participation of migrants in Switzerland (Giugni et al. 2014; Manatschal and Stadelmann-Steffen 2014) aligns with these results. Because the level of education is expected to positively influence mobilization on political issues, it is therefore more interesting to observe whether skill levels also affect forms of engagement. We mark people with only compulsory education as low-educated, those with higher secondary education and up to advanced technical or professional training as mid-educated and those with at least a bachelor’s degree as high-educated.

We include level of employment in the analysis with the expectation that those who are employed full-time will tend to engage less often than will those engaged part-time or who are not employed. According to Verba et al. (1995), time is one of the most important resources for participation. Respondents in our survey are considered not employed if they are seeking a job, undergoing training, looking after their home or in any other non-employed situation.

Having a good command of the language of the place of residence, measured through speaking skills, is considered an important resource for engaging with the local environment. Lack of local language skills and the perceived lack of effort to learn local languages has been at the core of accusations towards new migrants in Switzerland. Lack of communication abilities can be considered a reason for social exclusion (Ersanilli and Koopmans 2010) but, obviously, also a threat to national cohesion as exemplified by the remarks of politicians in Switzerland.

We also control for the respondents’ regions of birth and divide them into five regional groups according to their country of birth: Europe, Africa, South and Central America, Anglo-Saxon countries (USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand) and Asia.

6 Results

6.1 Descriptive Analysis

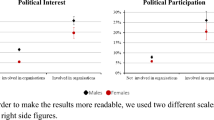

Before delving into the different forms of participation, we initially wanted to determine whether recent migrants, who are at the centre of our attention for this study, differ from the general Swiss population in terms of political interest. We name all respondents of the survey recent migrants because arrival in Switzerland within the past 10 years was one of the conditions to be included in the survey. The information for the general Swiss population was obtained from the European Social Survey (ESS), which worked as a model for several questions included in the Migration-Mobility Survey. The question on how interested the respondents are in politics in Switzerland is identical in both surveys and actually shows more people who say they are either very or quite interested in politics in Switzerland among recent migrants in the Migration-Mobility Survey than among the Swiss citizens in the European Social Survey (66.7% vs. 62.8%). The high level of political interest among migrants arriving within the past 10 years would not be anticipated if we believed the perceptions of migrants in the public debate.

Turning our attention to political behaviour, the picture is quite different. Of the respondents, 38.6% have done at least one of the mentioned activities within the past 12 months. Table 10.2 shows that except for boycotting products and expressing political opinions and communicating about activities on the internet, recent migrants are much more absent from political participation compared with Swiss citizens. The fact that behaviour on the internet and consumption show a different tendency could possibly be explained by structural and institutional barriers prevalent in other spheres that discourage migrant political participation. However, research that explored differences in the pattern of political participation between immigrants and the majority population found that explanatory mechanisms for participation work differently for immigrants than for the majority (de Rooij 2012). We suggest that levels of resources in terms of education and professional status must be combined with individuals’ migration background and experiences of migration to explain political mobilization.

Based on the list of nine possible forms of engagement in the survey, we create a dummy variable measuring the overall political participation. A given respondent might have picked only one of the activities or a number of them because multiple responses were possible. To identify the attributes that distinguish those politically active in different forms of political engagement, we divide activities into three major groups: contacting, expressive and quiet forms of activity. Given the exploratory nature of this chapter, we initially study the prevalence of different types of political involvement among respondents and break it down by their educational level (Table 10.3). Other studies have established that being more educated provides crucial resources for political participation. Therefore, it is not surprising that our data also show that individuals with high education are more likely to become involved in all types of activities. Almost 45% of highly educated respondents have participated in at least one form of activity. Among the low-educated, only 19% were engaged in any sort of political activity. The difference between high-educated and the rest is particularly large within the quiet forms of political engagement (boycotting products and signing petitions). Quiet forms of engagement are the most common among mid- and high-educated migrants, whereas low-educated migrants more often choose expressive forms of engagement. Examining more closely the types of activities that are clustered under the expressive forms, we ascertain that more-common engagement in this form is largely due to internet communication about political events.

In the explanatory analysis, we aim to observe how far political mobilization can be explained by factors other than the level of education. We are interested in not only whether recent migrants participate but also how their resource environment, which considers the specific migration experience, influences patterns of participation.

6.2 Explanatory Analysis

Table 10.4 shows the results of the binary logistic regression models for the three types of activities and for the overall political participation. Considering the results for overall participation, the most interesting finding is that almost all variables related to migration background and migration experiences have a significant effect on involvement. Only the feeling of general satisfaction in Switzerland and residence in different language regions of Switzerland lacked a significant effect on overall participation.

We observe that the resources environment works unevenly for different groups of activities. Level of democracy in respondent’s birth countries works as a determinant only for quiet activities. Coming from a place with more competitive possibilities of participation positively affects the use of quiet forms of engagement among recent migrants in Switzerland. Theories of political socialization stress the importance of early age for determining adult political behaviour (Verba et al. 1995). The use of petitions and boycotts might be more common in countries that are ranked as competitive in the Polity IV index, which would predispose migrants to engage through these forms.

The number of times people moved internationally is another variable displaying a strong effect. We find that people with rich international experiences, who had moved from country to country before migrating to Switzerland, can use their international experiences as a resource for political mobilization. We assumed that there would be a difference between those people who have moved a couple of times as opposed to those who have moved 10 or 20 times in their lives. Our results appear to support this assumption by showing that moving up to five times works (compared with only moving once to Switzerland) as a predictor for any type of activities and specifically for the quiet forms. In any case, this finding goes against the literature on conventional political participation, which considers international mobility a reason for low participation. Migrants are supposed to be less likely to be recruited by the mainstream social institutions and political organizations because they are difficult to reach (Ramakrishnan and Espenshade 2001). Our approach, which observes engagement at an individual level, allows us to go beyond restrictions imposed by mainstream institutions and manages to capture migrants’ activities when they happen outside the arena prescribed for politics. Thus, international mobility experiences actually are a resource. However, the longer people stay in the country, the more likely they are to engage politically, which aligns with the theory on the role of residential stability and social connectedness. They become easier to reach, possibly create additional social networks and might become more interested in the local place through their rootedness.

The feeling of discrimination is a strong motivator for engagement. Immigration is a transformational experience, and going through it might activate a new political identity (Nguyen Long 2016). A perception of exclusion could motivate people to seek other people with shared experiences and act as a measure of group consciousness. Although discrimination could be expected to work in two opposite directions, possibly leading to disillusionment with their new society, the effect for recent migrants in Switzerland works in favour of mobilizing. If an average person feels discriminated against, the probability of engaging increases by almost 16%.

Display of interest in current events in Switzerland also has an effect on all forms of participation. Political interest is a predisposition for participation found in studies concerning political participation in general and migrant political participation in particular (Giugni et al. 2014; Verba et al. 1995). It is a relevant predictor for all types of acts.

To observe the importance of context, our models include a language region. Living in a French-speaking canton increases the probability of migrants to be engaged in expressive forms, whereas living in the Italian-speaking canton decreases the probability of quiet forms of engagement. Higher engagement in the French-speaking cantons could be a response to less-restrictive integration policies and to a local population that is in general less sceptical towards migrants compared with the German-speaking cantons (Danaci 2009; Manatschal 2012).

We observe that respondents’ demographic background works unevenly for different groups of activities. Age, for example, has a significant effect concerning respondents’ probability of engaging in direct and expressive forms. Age does not appear to play a role when people sign a petition or boycott products. However, the possibility of being active in any of the expressive forms decreases for older migrants. Women traditionally participate less than men do (Giugni et al. 2014; Klandermans et al. 2008; Nguyen Long 2016). It is therefore not surprising that we come to the same finding based on our data. Being male is a rather strong predictor for expressive forms of engagement. However, gender does not appear to matter for quiet activities; men and women are equally likely to engage in this form.

Level of education is found to have the strongest effect on political engagement. Having a university education increases the probability of any type of engagement by 26.4% compared with the low-educated migrants. The strength of association between education and engagement is markedly more pronounced for unconventional forms of engagement, both the expressive and quiet ones. This strength might be due to the social esteem needed to engage in non-regulated political activities.

The variable on employment distinguishes those with full-time employment from those working part-time or who are not employed. Full-time employed tend to engage less in conventional acts of directly engaging with politicians. This behaviour could be explained by time availability; all of the activities grouped under “contacting activities” are listed as high-cost acts in the typology by de Rooij (2012). Not-employed are more likely to be engaged in expressive forms of activities, but overall level of employment does not affect different types of activities, which, according to the rationale by de Rooij, could mean that they are less time-demanding.

Political engagement grows with improvement of language skills. Host country language proficiency provides communication abilities and enables access to information. Language skills, however, do not predict that someone will engage through expressive patterns. Wearing a badge, joining a protest or engaging politically on the internet appear to be unaffected by the command of local languages, which suggests that not speaking Swiss German, French or Italian does not prevent people from mobilizing in these forms. Most likely, they will in this case target institutions other than the local government.

People born in regions other than Europe are less likely to engage in contacting activities. Specifically, respondents born in any of the African countries are significantly less likely to engage in these forms compared with those born in European countries. In contrast, respondents born in North America or Australia are more likely to be engaged in expressive activities.

7 Discussion and Conclusion

This chapter explores the engagement practices of recent migrants and observes how the “resource environment” specific to migrants influences their practices. We observe migrants’ political participation by drawing on the concept of “resource environment” specific to migrants. Responding to the observed inability of the prevailing approach of studying migrant political participation to explain diverse mobilizations within a stable institutional environment of a single country (Però 2008), we include the influence of varied migration backgrounds and experiences to add to the debate on what counts as a political resource.

Overall, our findings suggest that migration background and migration experiences have a significant effect on involvement. Furthermore, we observe that the resource environment works unevenly for different groups of activities. Activities that require delegates and representatives to act in the name of others do appear to be high-cost acts (de Rooij 2012). Our results show that one is more likely to be engaged in contacting activities if one has a good command of the local language, has stayed in Switzerland for a longer time and expresses a high level of political interest. Interestingly, the level of education does not increase the probability of acting in the representative political sphere by contacting, donating to or joining a political party or organization. Time spent in Switzerland and local language skills – likely related to the time spent in Switzerland – matter most for these types of activity. Expressive forms of engagement are more likely for younger men with university education. The variables on feeling discriminated and being politically interested are significant for all forms of activities. Language proficiency, however, does not affect these forms. People are not discouraged from joining demonstrations, expressing political matters on the internet or wearing a campaign badge. Finally, acting with the quiet forms increases with higher education, language proficiency, the number of times people have moved internationally, duration of stay and by a higher democracy level in the migrant’s birth country. It is interesting that the last variable is significant only for this form of activity. Political socialization in a more competitive system in a birth country does not translate to contacting politicians in a country of residence; nor does it affect expressive forms. However, for the quiet activities, which could be more self-actualizing than demanding for the others to change, the socialized norms of engaging carry over to adult-years in a different country. Moreover, level of employment does not appear to matter, giving an indication that one can do any of these activities regardless of working full-time or of related time constraints.

Our results show that migrants are not necessarily eager to gain access to the representative political sphere but might participate in other areas of engagement. The level of education is a strong predictor for unconventional forms of engagement, expressive and quiet ones. Agencies of migrant engagement relate to their political socialization and experiences of moving internationally, in which the feeling of discrimination acts prominently as a mobilizing force. The social esteem required to act against discrimination through non-regulated political activities appears to be coming from a high level of education and international experiences. When one feels discriminated against, the probability of becoming engaged through quiet or expressive forms is greater than of engaging with politicians.

Our approach considers that political patterns are becoming more individualized, direct and expressive (O’Toole and Gale 2013). Finding a motivation to join organizations or associations might be particularly challenging for migrants who have changed locations not that long ago and live in increasingly diverse societies. Because of these limitations in the literature in relation to new migrants, we argue that before proclaiming them apathetic, there is a need to expand our understanding of political engagement.

However, our approach does not allow us to observe the motivations behind actions and stays within the investigation of forms of engagement. Another limitation with our approach is that we cannot predict what explains more or less participation. A given respondent might have picked only one of the activities or a number of them because multiple responses were possible in the question used for our outcome variable. We do not have information on how often people engage in any of the activities or how intensely they prepared for any of the acts. Moreover, although this question was specifically designed to address the possible options of engagement for migrants, we nonetheless cannot claim to cover the full repertoire of political patterns and should therefore acknowledge the possibility of underestimating migrants’ mobilization.

To conclude, we wish to respond to some of the questions raised in the beginning of this chapter. Foreign residents are interested in the Swiss political system. They are making use of varied forms of engagement and are leaning towards forms that are not constrained by the representative political sphere within the borders of the nation-state. Moreover, it is indeed possible that the image of uninterested migrants is misplaced because attention is focussed more on the expectations of the receiving society than on what migrants actually do. Therefore, the notion of the Migration-Mobility nexus as observed through practices of political participation enables us to go beyond the traditional migration approach that limits migrants’ actions to the perspective of the nation states. Our findings show that new, selective and temporary patterns of mobility lead to broadening of political action repertoires. People on the move choose different types of activities, but their experiences of international mobility function as a resource for engagement.

Notes

- 1.

Translated by the author, “Wie viele Deutsche verträgt die Schweiz?” (Blick, 15 February 2007).

- 2.

Translated by the author, “Die Elite ist nicht integriert” (Tagesanzeiger, 5 May 2012).

- 3.

Translated by the author, “Ein Ausländerproblem der etwas anderen Art” (NZZ, 22 August 2012).

References

Aleksynska, M. (2008). Quantitative assessment of immigrants’ civic activities: Exploring the European social survey. In D. Vogel (Ed.), Highly active immigrants – A resource for European civil societies (pp. 59–74). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Bang, H. (2004). Culture governance: Governing self-reflexive modernity. Public Administration, 82(1), 157–190.

Barnes, S. H., & Kasse, M. W. (1979). Political action: Mass participation in five western democracies. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Beck, U. (1997). The reinvention of politics: Rethinking modernity in the global social order. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Bilodeau, A. (2008). Immigrants’ voice through protest politics in Canada and Australia: Assessing the impact of pre-migration political repression. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34(6), 975–1002.

Dacey, J. (2012, February 8). Language edict found tricky for foreign managers. Swissinfo. https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/language-edict-found-tricky-for-foreign-managers/32090286. Accessed 20 Feb 2018.

Danaci, D. (2009). Uncovering cross-national influences and within-nation heterogeneity of national identity. Working paper, University of Bern.

Daum, M., & Teuwsen, P. (2012, January 26). Wir sind sehr widersprüchlich. Die Zeit. http://www.zeit.de/2012/05/index?wt_zmc=fix.int.zonpme.zeitde.wall_abo.premium.packshot.cover.zech&utm_medium=fix&utm_campaign=wall_abo&utm_source=zeitde_zonpme_int&utm_content=premium_packshot_cover_zech. Accessed 8 Feb 2018.

de Rooij, E. A. (2012). Patterns of immigrant political participation: Explaining differences in types of political participation between immigrants and the majority population in Western Europe. European Sociological Review, 28(4), 455–481. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcr010.

Eggert, N., & Giugni, M. (2010). Does associational involvement spur political integration? Political interest and participation of three immigrant groups in Zurich. Swiss Political Science Review, 16(2), 175–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1662-6370.2010.tb00157.x.

EKM. (2018, September 5). Ausländerstimmrecht. Eidgenössische Migrationskommission EKM. https://www.ekm.admin.ch/ekm/de/home/buergerrecht%2D%2D-citoyennete/Citoy/stimmrecht.html. Accessed 9 May 2018.

Erdal, M. (2013). Migrant transnationalism and multi-layered integration: Norwegian-Pakistani migrants’ own reflections. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39(6), 983–999.

Erdal, M., & Oeppen, C. (2013). Migrant balancing acts: Understanding the interactions between integration and transnationalism. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 39(6), 867–884.

Ersanilli, E., & Koopmans, R. (2010). Rewarding integration? Citizenship regulations and the socio-cultural integration of immigrants in the Netherlands, France and Germany. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 36(5), 773–791. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691831003764318.

Fechter, A.-M. (2016). Transnational lives: Expatriates in Indonesia. London: Routledge.

Fennema, M., & Tillie, J. (2004). Do immigrant policies matter? Ethnic civic communities and immigrant policies in Amsterdam, Liège and Zurich. In R. Penninx, K. Kraal, M. Martinello, & Vertovec (Eds.), Citizenship in European cities. Immigrants, local politics and integration policies (pp. 85–106). Aldershot: Ashgate.

Fournier, A. (2012, May 21). Les «expats» sous les projecteurs alémaniques. Le Temps. https://www.letemps.ch/index.php/suisse/2012/05/21/expats-projecteurs-alemaniques. Accessed 2 July 2018.

Gerny, D. (2012, August 22). Ein Ausländerproblem der etwas anderen Art. Neue Zürcher Zeitung NZZ. https://www.nzz.ch/schweiz/ein-auslaenderproblem-der-etwas-anderen-art-1.17506385. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

Giddens, A. (2002). Runaway world: How globalisation is reshaping our lives. London: Profile.

Giugni, M., & Passy, F. (2004). Migrant mobilization between political institutions and citizenship regimes: A comparison of France and Switzerland. European Journal of Political Research, 43, 51–82.

Giugni, M., Michel, N., & Gianni, M. (2014). Associational involvement, social capital and the political participation of ethno-religious minorities: The case of Muslims in Switzerland. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(10), 1593–1613. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.864948.

Ireland, P. (1994). The policy challenge of ethnic diversity. Immigrant politics in France and Switzerland. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Isaakyan, I., & Triandafyllidou, A. (2014). Anglophone marriage-migrants in southern Europe: A study of expat nationalism and integration dynamics. International Review of Sociology, 24(3), 374–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2014.954333.

Klandermans, B., van der Toorn, J., & van Stekelenburg, J. (2008). Embeddedness and identity: How immigrants turn grievances into action. American Sociological Review, 73(6), 992–1012. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240807300606.

Koopmans, R., & Statham, P. (1999). Political claims analysis: Integration protest event and political discourse approaches. Mobilization, 4, 203–221.

Koopmans, R., Statham, P., Giugni, M., & Passy, F. (2005). Contested citizenship: Immigration and cultural diversity in Europe. Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press.

Larsen, C. A. (2011). Ethnic heterogeneity and public support for welfare: Is the American experience replicated in Britain, Sweden and Denmark? Scandinavian Political Studies, 34(4), 332–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2011.00276.x.

Levitt, P., Viterna, J., Mueller, A., & Lloyd, C. (2017). Transnational social protection: Setting the agenda. Oxford Development Studies, 45(1), 2–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2016.1239702.

Lien, P. (2004). Asian Americans and voting participation: Comparing racial and ethnic differences in recent US. Elections IMR, 25(1), 493–517.

Manatschal, A. (2012). Path-dependent or dynamic? Cantonal integration policies between regional citizenship traditions and right populist party politics. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35(2), 281–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.573221.

Manatschal, A., & Stadelmann-Steffen, I. (2014). Do integration policies affect immigrants’ voluntary engagement? An exploration at Switzerland’s subnational level. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40(3), 404–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.830496.

Marshall, M. G., Gurr, T. R., & Jaggers, K. (2017). Polity IV project: Dataset users’ manual (Manual). Center for Systemic Peace and Societal-Systems Research Inc.

McDonald, K. (2006). Global movements: Action and culture. Oxford: Blackwell.

Micheletti, M. (2004). Why more women? Issues of gender and political consumerism. In M. Micheletti, A. Føllesdal, & D. Stolle (Eds.), Politics, products, and markets. Exploring political consumerism past and present (pp. 245–264). New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Morales, L., & Giugni, M. (Eds.). (2011). Social capital, political participation and migration in Europe. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Morawska, E. (2009). A sociology of immigration. (Re)making multifaceted America. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Negi, N. J. (2013). Battling discrimination and social isolation: Psychological distress among Latino day laborers. American Journal of Community Psychology, 51(1–2), 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9548-0.

Nguyen Long, L. A. (2016). Does social capital affect immigrant political participation? Lessons from a small-N study of migrant political participation in Rome. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 17(3), 819–837. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-015-0434-0.

Norris, P. (2002). Democratic phoenix: Reinventing political activism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Toole, T., & Gale, R. (2013). Political engagement amongst ethnic minority young people: Making a difference. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

OECD/UNDESA. (2013). World migration in figures. Paris. https://www.oecd.org/els/mig/World-Migration-in-Figures.pdf. Accessed 2 July 2018.

Oppliger, M. (2013, March 14). Bei den Schweizern. Tageswoche. https://tageswoche.ch/politik/bei-den-schweizern/. Accessed 20 Feb 2018.

Però, D. (2008). Migrants’ mobilization and anthropology. Reflections from the experience of Latin Americans in the United Kingdom. In D. Reed-Danahay & C. B. Brettel (Eds.), Citizenship, political engagement, and belonging. Immigrants in Europe and the United States (pp. 103–123). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Però, D., & Solomon, J. (2010). Introduction: Migrant politics and mobilization. Exclusion, engagements, incorporation. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 33(1), 1–18.

Phillimore, J., Humphris, R., & Khan, K. (2018). Reciprocity for new migrant integration: Resource conservation, investment and exchange. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(2), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341709.

Ramakrishnan, S. K., & Espenshade, T. J. (2001). Immigrant incorporation and political participation in the United States. International Migration Review, 35, 870–909.

Riaño, Y. (2003). Migration of skilled Latin American women to Switzerland and their struggle for integration. In Y. Mutsuo (Ed.), Latin American emigration: Interregional comparison among North America, Europe and Japan (pp. 313–343). Osaka: Japan Centre for Area Studies, National Museum of Ethnoglogy.

Rüttimann, L. (2007, February 15). Wie viele Deutsche verträgt die Schweiz? Blick. https://www.blick.ch/news/schweiz/die-neue-serie-wie-viele-deutsche-vertraegt-die-schweiz-id127014.html. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

Schaffner, D. (2012, May 5). Die Elite ist nicht integriert. Tagesanzeiger. https://www.tagesanzeiger.ch/schweiz/standard/Die-Elite-ist-nicht-integriert/story/21559422. Accessed 5 Jan 2018.

Schneider-Sliwa, R. (2013). Internationale Fachkräfte in Basel (Basler Feldbuch: Berichte und Forschungen zur Humangeographie No. 37). Basel: Geographisch-Ethnologische Gesellschaft Basel.

Schulz, T., & Bailer, S. (2012). The impact of organisational attributes on political participation: Results of a multi-level survey from Switzerland. Swiss Political Science Review, 18(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1662-6370.2012.02052.x.

Senik, C., Stichnoth, H., & Van der Straeten, K. (2009). Immigration and natives’ attitudes towards the welfare state: Evidence from the European social survey. Social Indicators Research, 91(3), 345–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-008-9342-4.

Stadelmann-Steffen, I., & Freitag, M. (2011). Making civil society work: Models of democracy and their impact on civic engagement. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(3), 526–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764010362114.

Stolle, D., & Hooghe, M. (2005). Review article: Inaccurate, exceptional, one-sided or irrelevant? The debate about the alleged decline of social capital and civic engagement in Western societies. British Journal of Political Science, 35(1), 149–167.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office. (2017). Statistical data on Switzerland 2017 (No. 025–1700). Neuchâtel: Swiss Federal Statistical Office.

Trundle, C. (2014). Americans in Tuscany: Charity, compassion and belonging. New York: Berghahn.

van Bochove, M. (2012). Truly transnational: The political practices of middle-class migrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 38(10), 1551–1568. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2012.711042.

Van Hear, N. (2014). Reconsidering migration and class. International Migration Review, 48, 100–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12139.

Van Meeteren, M. (2012). Transnational activities and aspirations of irregular migrants in Belgium and the Netherlands. Global Networks, 12(3), 314–332.

Van Tubergen, F., & Kalmijn, M. (2005). Destination-language proficiency in cross-national perspective: A study of immigrant groups in nine Western countries. American Journal of Sociology, 110, 1412–1457.

Verba, S., Lehman Schlozman, K., & Brady, H. S. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic volunteerism in American politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wray-Lake, L., Syvertsen, A. K., & Flanagan, C. A. (2008). Contested citizenship and social exclusion: Adolescent Arab American immigrants’ views of the social contract. Applied Development Science, 12(2), 84–92.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Hercog, M. (2019). Skill Levels as a Political Resource: Political Practices of Recent Migrants in Switzerland. In: Steiner, I., Wanner, P. (eds) Migrants and Expats: The Swiss Migration and Mobility Nexus. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05671-1_10

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05671-1_10

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-05670-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-05671-1

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)