Abstract

The history of whale and dolphin (cetacean) research in Angolan waters is scant. Prior to the 2000s it primarily consisted of information from historical (1700s to the 1920s) and modern (1920s–1970s) whaling catches, from which baleen whales and the sperm whale were confirmed. Very few species were added to Angola’s cetacean checklist between the whaling era and the 2000s. However, observations since 2003 have confirmed Angola as a range state for at least 28 species, comprising seven baleen whales, two sperm whale species, at least two beaked whales, and at least 17 delphinids. There is potential for approximately seven more species to be identified in the region based on their known worldwide distributions. Angola has one of the most diverse cetacean faunas in Africa, and indeed worldwide, due to its varied seabed topography and transitional ocean climate which supports both (sub)tropical species and those associated with the Benguela Current. While no cetacean species are truly endemic to Angola, the country is one of few confirmed range states for the Critically Endangered Atlantic humpback dolphin and the Benguela-endemic Heaviside’s dolphin. Those species, together with endangered baleen whales and breeding populations of sperm and humpback whales, are highlighted as conservation priorities.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

The occurrence of cetaceans along the west coast of Africa in the eastern tropical Atlantic (ETA) is poorly-studied, due to factors including remoteness, the history of political unrest in many countries, deficiencies in funding and logistical support (especially for marine work requiring boats), and a lack of training programmes to support local marine scientists (Jefferson et al. 1997; Weir 2010a, 2011a,b). Located at the southern limit of the ETA, Angola is expected to support a diverse cetacean community due to its varied marine environment. This chapter provides the history of Angolan cetacean research, reviews cetacean biodiversity and identifies priorities for future research and conservation options.

Methods

Study Area

Angolan waters are defined as marine habitat from the coast to the 200 nautical mile seaward limit of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), which is located in oceanic habitat over 4000 m deep (Fig. 16.1). They extend from the southern border with Namibia (17°15′S) northwards to the border with the Republic of Congo in Cabinda (5°02′S), but excluding the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) EEZ which divides Angola from the exclave of Cabinda. Some maritime areas in the northernmost EEZ are the subject of disputed ownership with neighbouring countries (Fig. 16.1), but are included here in the non-political context of assessing cetacean occurrence.

Weir (2011a) described the oceanography of the Angolan EEZ as habitat for cetaceans. The Angolan continental shelf is widest in the north, extending to 80 km from the coast off Soyo where it is intersected by the deep Congo Canyon at the mouth of the Congo River. In the southern part of the country, the shelf is narrow and depth increases strongly, bringing deep waters (>1000 m) to within 15 km of the coast in places. The region is predominantly tropical, with warm (>24 °C) nutrient-poor water flowing southward from the Gulf of Guinea as the Angola Current. However, the Benguela Current influences the southern area, bringing nutrient-rich cold water northwards from Namibia. The two currents converge at latitudes of between 14° and 16°S (depending on season) to form the Angola–Benguela Front (Fig. 16.1).

Data

Published (and some available unpublished) papers and reports were reviewed for information on Angolan cetaceans (see Weir 2011a). Whaling catch statistics were acquired from the International Whaling Commission (IWC). Since 2003, Marine Mammal Observers (MMOs), sometimes supported by Passive Acoustic Monitoring (PAM), have been used during seismic surveys by the oil and gas industry to mitigate the potential impacts of airgun sound on cetaceans (Weir 2008). With the exception of published subsets, MMO data are not publicly available and are therefore not included here.

Species Identification

Cetaceans are often seen briefly and only partially by an observer, and there are morphological similarities between many species in the ETA region (e.g. within Stenella dolphins, beaked whales and Balaenoptera whales) that causes confusion. High potential for species misidentification exists, even for established cetacean observers and trained MMOs (many of whom lack previous field experience with the particular species occurring off Angola). Published records therefore require careful evaluation (e.g. Best 2001; Fertl et al. 2003; Weir et al. 2014), particularly records originating prior to the 2000s, after which knowledge of key identification features increased markedly with the advent of digital photography, modern field guides and genetic work. Consequently, some Angolan records were not considered sufficiently well-supported for inclusion (e.g., Brown 1959, Mörzer Bruyns 1971, Tormosov et al. 1980).

History of Cetacean Research in Angola

Angola’s Whaling Era

Whaling has been practiced since prehistoric times, and whaling data provides the earliest information available on the species identification, distribution, migrations and population status of whale stocks around the world. Whaling also generated much of the best-available information on the life histories, morphology and diet of large whales. Consequently, the whaling era is still considered a prime source of scientific data on the larger baleen whales and the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus).

It was not until the 1700s that American pelagic whalers first visited the west coast of Africa in search of the relatively slow-moving and oil-rich sperm whales and southern right whales (Eubalaena australis). They reached the coast of Angola by 1770 (Best 1981), and catches from this period onward provide the earliest documentation of whale species in Angola. The distribution of certain whales as shown by logbook records of American whale ships, published by Charles Haskins Townsend in 1935, included the capture locations of over 50,000 whales taken during American pelagic whaling between 1761 and 1920, including three species from Angolan waters (sperm whales, southern right whales and humpback whales, Megaptera novaeangliae: Fig. 16.2). Similar and expanded analyses of whaling logbook catch datasets including Angolan waters have also been published by other authors (e.g., Richards 2009; Smith et al. 2012).

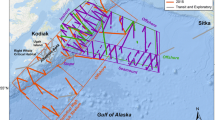

Distribution of whale catch positions in the Angola EEZ. MV Sierra catches from the IWC database (Allison 2016b). Digitised Townsend (1935) charts are available from https://canada.wcs.org/wild-places/global-conservation/townsend-whaling-charts.aspx

Whaling changed drastically from the mid-1800s with the development of exploding harpoon guns, modern steam-driven whaling boats (‘catcher boats’), cannon-fired bow-mounted harpoons and the technique of inflating dead whales with air to keep them afloat (Harmer 1928; Mackintosh 1965; Tønnessen and Johnsen 1982). Species that had previously been inaccessible to whalers, especially the Balaenoptera whales that were fast-swimming and sank after death, could now be harvested, and were either towed to shore stations or processed at factory vessels moored in coastal bays. Shore-based whaling stations were established in several African countries during the early 1900s (Tønnessen and Johnsen 1982; Best 1994). Summarised statistics on whale catches worldwide since 1900 (together with some incomplete information on catches taken in the late 1800s) are maintained by the IWC (Allison 2016a). There is also a catch database for individual captures that contains date, length, sex, foetus details, stomach contents and location (when those are available; Allison 2016b). These databases are continually updated (Allison and Smith 2004), and consequently the total species catches reported by various sources has altered over time (e.g. Best 1994; Figueiredo and Weir 2014; this chapter). Catches of whales in Angola since 1900 are presented in Table 16.1.

The first modern coastal whaling operation in Angola was established at Tômbwa (formerly Porto Alexandre), with the moored Norwegian factory ship Ambra taking around 237 whales in 1909 (number revised by the IWC from 270 whales in earlier sources; Figueiredo 1960; Tønnessen and Johnsen 1982; Best 1994). The Ambra returned to Tômbwa in 1910 and took 650 whales, with a second operation (shore station and a Portuguese catcher vessel) commencing at Moçâmedes and taking around 70 whales (Mackintosh 1942; Best 1994; Allison 2016a, b). Operations increased during 1911, with the issuing of five licenses to Norwegian floating factory ships (based at Tômbwa, Lobito, Baía dos Elefantes and Baía dos Tigres) at the end of 1910, and the continuation of the Portuguese operation at Moçâmedes (Figueiredo 1960, Allison 2016a, b). Whaling in Angola boomed between 1911 and 1914, capturing over 10,000 animals (mostly humpbacks: Table 16.1). However, the catch in 1914 was half that of 1912 and 1913, and a collapse in whale stocks was suggested (Figueiredo 1960). The combination of declining whale stocks and the occurrence of the First World War meant that no whales were caught off Angola between 1917 and 1922 (Best 1994).

Whaling was re-established off Angola in 1923, with a Norwegian floating factory ship operating just outside of territorial waters, and coastal operations resuming at Baía dos Elefantes and Moçâmedes between 1924 and 1928. This second period did not yield sufficient captures to be profitable (Table 16.1), and marked the end of coastal whaling from Angolan shore stations (Figueiredo 1960; Tønnessen and Johnsen 1982).

The 1920s saw the development of new ocean-going factory ships (fitted with a stern slipway and a flensing station to process whales) that could operate for long periods with a fleet of smaller catcher vessels and allowed whaling to move into offshore waters. Between 1934 and 1937 the Norwegian factory ships Pioner, Haugar and Norskhavet operated in the ETA including Angola. Catches in Angolan waters over this period included one blue (Balaenoptera musculus), 22 fin (B. physalus), 24 humpback, 16 sei/Bryde’s (B. borealis/B. edeni), and 46 sperm whales (Allison 2016b). In later decades factory ships opportunistically took sperm whales encountered while transiting through Angolan waters. For example, the Olympic Challenger caught 20 in March 1956, the Peder Huse took 41 in early 1971, and the Sovetskaya Ukraina took 90 in 1975 and 1976 (Mikhalev et al. 1981a; Allison 2016b).

Most recently, the combined catcher/factory vessel MV ‘Run/Sierra’ operated year-round between South Africa and the Gulf of Guinea during the 1970s. The IWC database includes 801 whales taken by the vessel in the Angolan EEZ between 1971 and 1975, comprising five minke whales, three sperm whales and 793 ‘sei whales’ (Fig. 16.2; Allison 2016a,b). However, the Run/Sierra ‘sei whale’ catches are now considered to predominantly comprise Bryde’s whales (Tønnessen and Johnsen 1982; Best 1996, 2001).

The composition of whaling catch data altered over time as each species declined to levels where protection in the Southern Hemisphere was introduced by the IWC, beginning with the southern right whale in the 1930s, continuing with the blue and humpback whales in the 1960s, fin and sei whales in the 1970s, and finally with the worldwide ban on the exploitation of all whale species under the 1986 moratorium. Consequently, the whaling era in Angola was ended in the 1970s by the protection of most Southern Hemisphere whale stocks.

Opportunistic Sightings and Specimen Records

Weir (2011a) recognised a ‘stranding and specimen era’ of cetacean research in the ETA (1950s–1970s), during which new information emerged on the taxonomy, morphometry and distribution of many small cetaceans (see Cadenat 1959, Jefferson et al. 1997). However, the majority of this work was carried out by French scientists in Mauritania, Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire, and the only information emerging from Angola during this period appears to be the 1972 paper of Bree and Purves, which included a single skull from Angola in an evaluation of the Delphinus genus. Some opportunistic sightings in Angolan waters by the Dutch sea captain Mörzer Bruyns were also published (Mörzer Bruyns 1968, 1971), although the species identification for many of his records cannot be confirmed. Effort has been made to locate cetacean specimens that may have been captured off Angola during this period and preserved by naturalists in Lisbon museum collections. However, it appears that no cetaceans from Angola are present in Portuguese collections (Cornelis Hazevoet, pers. comm.). The dearth of papers from Angola in this period was also noted in the compilation of African cetacean research by Elwen et al. (2011).

During the 1980s and 1990s a few publications from the wider Atlantic region included opportunistic at-sea sightings (species identifications unsupported) from Angolan waters, for example Tormosov et al. (1980), Mikhalev et al. (1981b) and Wilson et al. (1987). In 1997 Jefferson et al. published a review of dolphin and porpoise records off West Africa, but their study area (to 6°S) included only the exclave of Cabinda and not the rest of Angola. The only ‘Angolan’ cetacean records located by Jefferson et al. (1997) were common dolphins (Delphinus sp.) reported by Simmons (1968). However, careful reading of Simmons (1968) indicates that the observations were actually recorded off Cape Palmas in Liberia rather than Angola.

Targeted At-Sea Cetacean Surveys

Although instability related to the Angolan civil war from 1975 to 2002 is known to have interrupted field studies of terrestrial fauna (other chapters, this volume), dedicated cetacean research had still not yet developed prior to the outbreak of war. In fact, the first dedicated field study of cetaceans in Angolan waters began during the final period of the war in September 1998, when the Whale Unit of the Mammal Research Institute in South Africa was invited to northern Angola (6°52′S) by an oil company to conduct a preliminary investigation into large numbers of humpback whales reported in the area. This initial field study was successful in acquiring acoustic and behavioural data, photographing whale tail flukes for photo-identification and acquiring 13 genetic samples via biopsy sampling (Best et al. 1999). Although the authors recommended that a full survey programme should be initiated to assess the distribution, abundance and status of humpback whales in Angolan waters using aerial surveys and small boat work, such work never developed.

During the early 2000s, some cetacean data were collected concurrently with pelagic fish abundance assessments in Angolan waters as part of an agreement between the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research (IMR) and the Angolan Instituto de Investigação Pesqueira e Marinha (INIP). The IMR research vessel Dr Fridtjof Nansen surveyed a series of transects across the continental shelf in the Angolan EEZ. These investigations were carried out in cooperation with the Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem (BCLME) research programme. Cruise reports outlining the fish stock results are available from the IMR website, and cetacean observations are included for surveys (all between July and September) in 2003 (Krakstad et al. 2003), in 2004 (Axelsen et al. 2004), in 2005 (Axelsen et al. 2005, Roux et al. 2007), and in 2015 (Michalsen et al. 2015).

The Best et al. (1999) study was the first of several suites of cetacean survey work in Angola to be associated with, and funded by, the burgeoning oil and gas industry. From 2003 many oil companies began to use MMOs during their seismic surveys in Angolan waters, leading to a sudden increase in the potential for biologists to use geophysical survey vessels as ‘platforms of opportunity’ to collect data on cetacean occurrence. This was a landmark development in the documentation of Angola’s cetacean biodiversity, since many seismic surveys covered deep, oceanic waters that had previously been inaccessible to cetacean scientists. A resulting surge of information on Angolan cetacean occurrence was published from 2006 to 2014 including: (1) the documentation of species records for Angola (Weir 2006a, b, c, Weir et al. 2008, 2010, 2014); (2) evaluations of seasonal relative abundance and spatial distribution (Weir 2007, 2011a, b); (3) examinations of morphology and taxonomy (Weir and Coles 2007, Weir et al. 2014); (4) assessment of habitat preferences (Weir et al. 2012); and (5) studies of behaviour (Weir 2008). Weir (2010a) also published a comprehensive review of cetacean records in the Angola to Gulf of Guinea region, which together with her fieldwork on oceanic cetaceans and Atlantic humpback dolphins was published as the first doctoral thesis focused on Angolan cetaceans (Weir 2011a).

Between 2008 and 2009, some marine mammal survey work was also carried out in association with the construction of a Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) terminal at the mouth of the Congo River at Soyo, including the use of Marine Autonomous Recording Units (MARUs) between March and December 2008 at two locations along the edge of the Congo Canyon (6°S). The MARUs recorded singing humpback whales between June and early December (Cerchio et al. 2014), and blue whale calls on one date in October (Cerchio et al. 2010).

The year 2008 saw the onset of independent (non-industry) cetacean field research, when Weir (2009, 2011a) visited Namibe Province in southern Angola during two seasons to conduct an ecological study of the Atlantic humpback dolphin. That work provided the first comprehensive assessment of an Atlantic humpback dolphin population, collecting information on abundance (via photo-identification), distribution, movements, seasonality and behaviour (including vocal behaviour: Weir 2010b). The study also produced information on several other cetacean species in coastal waters (Weir 2010c).

Cetacean Species Recorded in Angola

A checklist of Angolan cetacean species is provided in Table 16.2 and some images of the most frequently-recorded species are shown in Fig. 16.3. The SMM (2018) currently recognises 89 species of cetacean worldwide, of which 28 (including unidentified beaked whales of the Mesoplodon genus, and only accounting for a single species of common dolphin) have been confirmed to occur in Angola to date. At least seven further species might potentially be added to Angola’s fauna in the future.

Photographs of the 10 most frequently-recorded cetacean species in Angolan waters (>55 records; Weir 2011a, b): (a) Bryde’s whale; (b) humpback whale; (c) sperm whale; (d) short-finned pilot whale; (e) Atlantic humpback dolphin; (f) Risso’s dolphin; (g) bottlenose dolphin; (h) Atlantic spotted dolphin; (i) striped dolphin; and (j) common dolphin. All photographs taken in Angolan waters by the author

Baleen Whales

Southern right whale—The majority of Angolan records are from Baía dos Tigres (17°S), which was the northernmost ground for southern right whale catches in the 1700s and 1800s; over 30 were taken there in 1801 (Best 1981; Richards 2009). Catches occurred predominantly in June and July (and thus likely represent a winter breeding presence: Best 1981). The northernmost record in Angola is at approximately 6°S to the southwest of the Congo River mouth (Townsend 1935), but may be atypical. An animal taken off Tômbwa in 1913 is the only record in the 1900s (Table 16.1; Allison 2016a). Best (1990) reported that a catch of 17 right whales at Baía dos Elefantes during 1925 was probably erroneous and actually related to Bryde’s whales.

Blue whale―A comprehensive review of blue whale records in Angolan waters was provided by Figueiredo and Weir (2014). Over 2000 blue whales were captured off Angola between 1909 and 1928 (Table 16.1; Allison 2016a), and all were landed at stations in the southern half of Angola (south of 13°S). A single animal was also taken close to Baía dos Tigres in 1934 (Figueiredo and Weir 2014). Several blue whale calls were recorded on an acoustic device off the Congo River mouth (6°S) in October 2008 (Cerchio et al. 2010). Four photographically-verified sightings of blue whales were recently reported from deep waters (>1000 m) off central Angola, at latitudes between 11 and 12°30′S (Figueiredo and Weir 2014). The presence of calves in whaling catches and one sighting indicates the potential use of Angolan waters as a calving or nursery ground (Figueiredo and Weir 2014).

Fin whale―Primarily documented from whaling catches, with over 800 animals captured off Angola between 1910 and 1928, and an additional 22 taken by pelagic whalers between 1934 and 1936 (Table 16.1; Allison 2016a, b). Four sightings were reported off Angola between 2003 and 2006 (Weir 2007); however, two of those were downgraded after subsequent evaluation (Weir 2011a, b). The two remaining sightings occurred in deep-water (>1500 m) during winter (August).

Sei and Bryde’s whales―It is considered that the majority of reported ‘sei whale’ catches in the ETA were misidentifications and more likely comprised Bryde’s whales (Harmer 1928, Ruud 1952, Best 1994, 1996, 2001). An estimated total of 1837 sei/Bryde’s whales were landed at Angolan shore stations between 1911 and 1928, with a further 809 animals taken by pelagic whalers between 1934 and 1975 (Table 16.1; Harmer 1928; Best 1994; Allison 2016a, b). The majority of pelagic catches were included in the comprehensive assessment of the distribution, migration and diet of ETA Bryde’s whales by Best (1996, 2001). Only one sighting of sei whales has been reported for Angola; two animals observed in deep water southwest of Soyo during August 2004 (Weir 2007). In contrast, 63 sightings of Bryde’s whales were recorded off northern Angola, mostly in oceanic waters of 1000 to 3000 m depth (Weir 2007, 2011a, b). Bryde’s whales have also been confirmed in central and southern Angola, from the Nansen surveys (Axelsen et al. 2004, 2005), during coastal dolphin surveys off Namibe Province (Weir 2010c), north of Baía dos Tigres (Dyer 2007), and off Tômbwa and Lobito (Olsen 1913). Best (1996, 2001) described a seasonal migration of the offshore Bryde’s whale population in and out of Angolan waters. However, sightings have been reported year-round (Weir 2007, 2010c, 2011a, b), although seasonal fluctuations occur. For example, Weir (2010c) only recorded Bryde’s whales during the summer in coastal Namibe Province, while most sightings from northern Angola are in winter and spring (August and September; Weir 2011a, b).

Minke whale―While there are unspecific mentions of minke whales off Angola in several sources (e.g. Mörzer Bruyns 1971; Stewart and Leatherwood 1985), the number of verified records is very low. The vessel Run/Sierra caught five Antarctic minke whales at latitudes of 5°S to 16°S (Allison 2016b). An Antarctic minke whale stranded at the Coroca River mouth near Tômbwa (15°45′S) during March 1970 (photograph held in the Museu do Mar, Cascais, Portugal; Peter Best pers. comm.), also confirming this species in Angolan waters (Best 2007).

Humpback whale―Townsend (1935) noted that the region between the equator and 12°S produced the highest nineteenth century humpback catches on the west coast of Africa, particularly between June and October. Angolan whaling catches from 1909 to 1928 included over 10,000 humpbacks, with a strong peak between 1911 and 1913 (Table 16.1; Best 1994; Allison 2016a). No new information on humpback whales emerged until the 1998 field study off northern Angola by Best et al. (1999), which recorded many surface-active groups, cow-calf pairs and singing males, and led those authors to conclude that the area was (or was very close to) a breeding ground. Acoustic monitoring off northern Angola (6°S) during 2008 recorded humpback whale singing activity, which was also considered indicative of breeding behaviour (Cerchio et al. 2014). Numerous sightings of humpback whales have been recorded during sighting surveys, including in southern Angola (Axelsen et al. 2004; Dyer 2007; Weir 2010c), central regions (Krakstad et al. 2003; Axelsen et al. 2005; Roux et al. 2007; Michalsen et al. 2015), and the northern areas off Soyo and Cabinda (Weir 2007, 2011a, b). The highest densities occur over the shelf, but sightings also occur far offshore (to at least 4000 m depth: Weir 2011b). Strong seasonality is evident in Angolan waters, with all captures, sightings and acoustic records occurring between May and January, and with a strong peak between July and October (Weir 2011a, b; Cerchio et al. 2014). The humpback whales using Angolan waters originate from Southern Hemisphere IWC stock B (Rosenbaum et al. 2009), and migrate between breeding areas in the ETA and summer Antarctic feeding grounds.

Synopsis―Both whaling data and sightings surveys indicate that humpback and Bryde’s whales are the most numerous baleen whale species in the region, with the remaining species either naturally less common or still to recover from whaling exploitation. The timing of catches (Allison 2016a, b), and observations from year-round sighting surveys (Weir 2011a, b), indicate that most baleen whales exhibit strong seasonality in Angolan waters, occurring during the austral winter and spring (June to October) which corresponds with the breeding period of Southern Hemisphere whale stocks. There is evidence for breeding in Angolan waters of at least humpback whales and blue whales. Many humpback whales may also use Angolan waters as a migratory corridor to reach well-established calving grounds off Gabon and in the Gulf of Guinea (Rosenbaum et al. 2009). The Bryde’s whale is one of few baleen whale species that inhabit warm waters year-round (Best 2001), and its seasonal movements in Angolan waters more likely relate to prey availability. Although there are no confirmed records to date in Angola, three additional baleen whale species may be recorded in the future including two documented elsewhere from warm Atlantic Ocean waters (Common minke whale Balaenoptera acutorostrata and Omura’s whale B. omuraii) and one cool water species that has been recorded further south off northern Namibia (19°28′S; pygmy right whale Caperea marginata; Leeney et al. 2013) and could extend into the Benguela-influenced waters of southern Angola.

Sperm Whales

Sperm whale―The whaling charts of Townsend (1935) reveal numerous sperm whale captures on the ‘Coast of Africa’ whaling ground (3–23°S), including the entire coast of Angola. Over 500 sperm whales were landed at Angolan shore stations between 1912 and 1928, with an additional 200 taken by pelagic fleets from the 1930s to the 1970s (Table 16.1; Harmer 1928; Mikhalev et al. 1981a; Best 1994; Allison 2016a, b). Sighting surveys in Angolan waters found that the sperm whale was one of the most frequently-recorded cetacean species (Weir 2011a, b). Sightings were distributed exclusively in deep waters from 800 to 3800 m and usually comprised singletons or nursery schools of ≤20 animals, although loose aggregations of up to 65 animals have been observed (Weir 2011a, b). Sperm whales are present in Angolan waters year-round, but there may be fine-scale spatio-temporal fluctuations in their occurrence and an overall preference for warmer waters where sea surface temperatures (SSTs) exceed 23 °C (Weir et al. 2012).

Dwarf sperm whale―Twenty-six sightings of this species were reported by Weir (2011a, b) from Angolan waters, comprising small groups of one to three animals seen in deep waters in the 1000–2000 m range. The closely-related pygmy sperm whale (Kogia breviceps) has not been confirmed off Angola to date, but may be expected to occur based on its worldwide distribution (Caldwell and Caldwell 1989).

Beaked Whales

Of the 22 currently-recognised beaked whale species (SMM 2018), only the Cuvier’s beaked whale (Ziphius cavirostris) has been positively-confirmed in Angolan waters to date, with four sightings in slope waters of 847–2040 m depth (Weir 2006a, 2011a, b). Eleven additional sightings of unidentified beaked whales (including Mesoplodon species) are documented off Angola in deep waters exceeding 730 m (Weir 2006a, 2011a, b). Mörzer Bruyns (1968) also observed three unidentified Mesoplodon whales off Angola in July 1966. There is one record of a stranded adult male Gervais’ beaked whale (Mesoplodon europaeus) from the mouth of the Cunene River (on the Angola–Namibia border) in 1997. Although considered a Namibian record (Griffin and Coetzee 2005), this stranding is highly-supportive of an occurrence in Angolan waters. The warm Atlantic distribution of Blainville’s beaked whale (M. densirostris; MacLeod et al. 2006) is also indicative of a likely occurrence off Angola.

Delphinids

Killer whale―Records in Angola include observations south of Moçâmedes during July 1966 (Mörzer Bruyns 1971), from a pelagic whaler (Mikhalev et al. 1981b), and from the Nansen surveys (Axelsen et al. 2005). Weir et al. (2010) provided information on 18 sightings from Angolan waters between 1991 and 2008. An additional two sightings were reported in 2009 (Weir 2011a, b). Sightings have comprised 1 to 12 animals observed at latitudes of 5°S to 12°S and in water depths ranging from very shallow coastal waters to well over 2000 m. In January 2005, a group of five killer whales was seen attacking sperm whales off northern Angola (Weir et al. 2010).

Short-finned pilot whale―All pilot whales observed in northern Angola to date have been conclusively identified as the short-finned pilot whale (Globicephala macrorhynchus). However, it is likely that long-finned pilot whales (G. melas) also occur in the Benguela Current-influenced areas and will be confirmed in the future. Pilot whales were the third most frequently-observed species in Angolan waters (perhaps partly because they are easy to identify at distance), with 125 sightings reported by Weir (2011a, b). Over 94% of sightings consisted of ≤50 animals, and all records were located over the slope or in oceanic waters (400–4000 m depth). This species was also reported by Krakstad et al. (2003), Axelsen et al. (2004, 2005) and Dyer (2007).

False killer whale―Thirteen sightings of false killer whales were reported in oceanic habitat (1400–2600 m depth) off northern Angola, comprising groups of 2–50 animals (Weir 2011a, b).

Melon-headed whale―Four sightings of melon-headed whales have been reported in oceanic waters (>1300 m depth) off the northern half of Angola (Weir 2011a, b). Three of the schools were large, comprising 100–300 animals.

Atlantic humpback dolphin―First documented in Angola from a photograph taken near Tômbwa in 2004 (Van Waerebeek et al. 2004). The ‘numerous reports’ cited in Van Waerebeek et al. (2004) from opportunistic observers in northern Angola and Cabinda have not been upheld by subsequent scientific fieldwork in those areas (Weir 2009, 2011a; Weir and Collins 2015), and are considered likely misidentifications. Dedicated photo-identification surveys in Namibe Province in January and June/July 2008 revealed a very small population of 10 humpback dolphins that inhabit nearshore (<1.4 km) waters along a small 40 km stretch of coast year-round, and use the area for both feeding and calving (Weir 2009, 2010c). Published information on the whistles of this species represents one of few cetacean acoustic studies in Angola to date (Weir 2010b).

Rough-toothed dolphin―Weir (2006b) reported three sightings of rough-toothed dolphins from Angolan waters in 2004 and 2005, while Weir (2011a, b) added an additional 15 sightings up until 2009. All records were seaward of the shelf (700–2200 m), and usually comprised ≤60 animals although several larger groups were observed. An interesting account of an interaction between rough-toothed dolphins and a sport fishing tournament off Luanda was described by Weir and Nicolson (2014), with dolphins taking bait from the fishing lines of several vessels.

Dusky dolphin―Two were photographed off Lobito (12°22′S: Kramer 1961; Findlay et al. 1992; Best and Meÿer 2009). A group of 40 was reported by Axelsen et al. (2004) at 16°48′S off Baía dos Tigres, while four schools of 6–40 animals were recorded during August 2005 south of 16°06′S (Axelsen et al. 2005; Roux et al. 2007). Dyer (2007) observed a group of six at 15°40′S just north of Tômbwa. Dusky dolphins inhabit cool Benguela Current-influenced waters along the west coast of Africa, and are likely limited to southern Angola.

Risso’s dolphin―A total of 75 Angolan sightings was described in Weir (2011a, b), and included in the global review of Jefferson et al. (2013). Sightings occurred in slope and oceanic habitat from 900 to 2500 m depth. Group size was generally ≤10 animals, but some larger groups of 35–75 animals were recorded.

Bottlenose dolphin―Fifty-six sightings were reported in Angolan waters by Weir (2011a, b), occurring in water depths varying from 10 m by the coast to 3700 m in oceanic areas. Group size in Angola is typically small at 15 or fewer animals, and in oceanic regions they frequently form mixed-species associations with pilot whales (Weir 2011a, b). They have also been regularly reported during the Nansen surveys, including mixed groups with pilot whales (Krakstad et al. 2003, Axelsen et al. 2004, 2005). Weir (2010c) reported 24 sightings (1–50 animals) in the coastal waters between Tômbwa and Moçâmedes in 2008, with more frequent sightings during the winter.

Pantropical spotted dolphin―Weir (2011a, b) reported four sightings from Angola in slope and oceanic habitat (≥820 m depth) north of 8°40’S. The groups ranged from 50 to 200 animals.

Atlantic spotted dolphin―A total of 101 sightings was recorded by Weir (2011b), making it the most commonly recorded species of the Stenella genus in Angola. Water depth ranged from 800 to 3000 m, and group sizes were 1–500 animals.

Spinner dolphin―A single sighting exists for Angola, comprising three animals in 1000 m depth off northern Angola in 2004 (Weir 2007, 2011a, b). There have been 11 additional sightings of animals identified as either spinner or Clymene dolphins, but too distant to confirm (Weir 2011a).

Clymene dolphin―The first record for Angola was reported by Weir (2006c). A comprehensive review of Clymene dolphins in the ETA was conducted by Weir et al. (2014) and included 16 records for Angola from 6°S off the Congo River to 14°S. Clymene dolphins in Angola were sighted in water depths ranging from 466 to 2362 m, and in groups of 12 to 1000 animals (Weir et al. 2014).

Striped dolphin―Two sightings were reported by Wilson et al. (1987; No’s 40082 and 40083) at 13°59′S and 09°15′S off central Angola in October 1974. A total of 66 sightings were reported from the northern half of Angola by Weir (2011a, b), occurring in slope and oceanic waters from 800 to 2700 m depth.

Common dolphin―The taxonomic status of Delphinus dolphins worldwide remains unresolved (Cunha et al. 2015). A few Angolan common dolphin skulls have been included in morphological analyses of the Delphinus genus (Bree and Purves 1972), identifying ‘short-beaked’ and ‘long-beaked’ forms (Van Waerebeek 1997). However, these may be morphotypes of a single species (Cunha et al. 2015). The external appearance of Angolan animals appears intermediate between short-beaked (D. delphis) and long-beaked (D. capensis) common dolphins (Weir and Coles 2007; Weir 2011a), and until their taxonomy is better clarified then they are referred to simply as ‘common dolphin’. The surveys by Weir (2011a, b) reported 62 sightings of common dolphins off Angola, including in shelf, slope and oceanic habitat (to 2600 m depth), and in group sizes of up to 500 animals. Sightings have been reported as far south as Moçâmedes (15°20′S: Axelsen et al. 2004). Weir et al. (2012) identified a preference for cooler SSTs (≥22.1 °C) in Angola, suggesting the species is associated with areas of upwelling.

Fraser’s dolphin―The occurrence of Fraser’s dolphins off Angola was first described by Weir et al. (2008) from two sightings recorded in 2007 and 2008. An additional record was added by Weir (2011a, b). All sightings have occurred at latitudes of around 07°30’S off northern Angola, and in deep waters exceeding 1300 m.

Heaviside’s dolphin―Two animals were caught by a trawler approximately 12 km north of the Cunene River mouth near the Angola-Namibia border (17°09’S: Findlay et al. 1992; Peter Best pers. comm.). Another was caught in a fishing net off the Cunene River mouth just south of Angola during January 1982 (Windhoek Museum specimen WM 11708; Peter Best pers. comm.), supporting an occurrence in southern Angolan waters. Two Heaviside’s dolphin sightings were recorded during the Nansen 2004 surveys, in water depths of 20–120 m and at latitudes south of 16°48′S between Baía dos Tigres and the Namibian border (Axelsen et al. 2004, Best 2007). This species appears to inhabit water temperatures ≤15 °C (Best and Abernethy 1994), and is likely restricted to Benguela-influenced regions in the far south of Angola (Best 2007).

Synopsis―At least 17 delphinid species have been confirmed in Angolan waters (assuming only one species of Delphinus). Most are likely to occur year-round, although there may be seasonal fluctuations in the distributions of some species depending on the extent of the Benguela Current influence. This applies particularly to dusky dolphins and Heaviside’s dolphins, which reach the northern limits of their African distribution range in the southern part of Angola. Sighting surveys indicated that some delphinid species were relatively more common than others off Angola, with Atlantic spotted and common dolphins being frequently-sighted, while pantropical spotted and spinner dolphins were far less common. The relative frequency of dolphin species likely relates to (at least) water temperature, water depth and productivity, with some niche partitioning evident (Weir et al. 2012). Despite large amounts of survey effort in suitable habitat, there are no published (verified) sightings of the pygmy killer whale (Feresa attenuata) to date in Angola. This species is likely to be added to the Angola cetacean list in the future, along with the long-finned pilot whale.

Endemism

As highly mobile oceanic predators, none of the reported cetacean species are endemic to Angolan waters. However, four species are endemic to the Atlantic Ocean, including the Atlantic spotted dolphin, Clymene dolphin, Atlantic humpback dolphin and the Heaviside’s dolphin. The latter two species have restricted geographic ranges, with the Atlantic humpback dolphin occurring only in nearshore waters of the ETA (Weir and Collins 2015), and the Heaviside’s dolphin occupying cool shelf waters of the Benguela Current system (Best and Abernethy 1994). Consequently, Angolan waters are of particular relevance for those species in terms of their very limited global range.

Cetacean Biodiversity and the Marine Environment

The occurrence of cetacean species is strongly related to seabed topography (i.e. depth, slope) and oceanographic variables such as SST, turbidity, salinity and chlorophyll (e.g. Davis et al. 2002; Hamazaki 2002). Consequently, cetacean biodiversity in Angola varies according to habitat (Weir et al. 2012).

Large marine ecosystems (LMEs) have been recognised worldwide based on ecological criteria including bathymetry, hydrography, productivity, and trophically-dependent populations, with the majority of the Angolan EEZ situated within the Benguela Current LME (Fig. 16.1; Sherman 2014). The Angola Front at 5°S forms the northern limit of the Benguela Current LME, and the waters off Cabinda therefore fall into the tropical Guinea Current LME. A biogeographic system to classify marine regions was also developed by Spalding et al. (2007) for coastal waters. In this system, the majority of the Angolan EEZ is situated in the Angolan ecoregion of the Gulf of Guinea province in the Tropical Atlantic realm (Fig. 16.1). However, the northernmost area (north of 6°30′S) falls into the more tropical Gulf of Guinea South ecoregion, while the area south of 15°45′S is recognised as an entirely different biogeographic region located in the Namib ecoregion of the Benguela province in the Temperate Southern Africa realm (Spalding et al. 2007). Consequently, both the LME (Sherman 2014) and marine ecoregion (Spalding et al. 2007) approaches support transition zones within the Angolan EEZ between tropical and temperate (Benguela-influenced) biomes.

Cetacean species in Angola can be broadly classified into communities, based on their occurrence in shelf (less than 200 m depth) versus oceanic (greater than 200 m depth) waters and on their distribution according to marine ecoregion (which broadly corresponds with water temperatures). Using this method, three distinct communities are apparent, with the most diverse comprising the warm water species found in oceanic waters (Fig. 16.4). A second community inhabits cool shelf waters in the south of the study area, while the Atlantic humpback dolphin occupies a unique niche being found only in warm waters on the shelf. There are also six species that might be expected to occur throughout the temperature range, primarily comprising the migrating baleen whales and several very cosmopolitan species (e.g. killer whales, bottlenose dolphin and common dolphin) that occupy wide habitat ranges (Fig. 16.4). This system is a useful starting point for considering the underlying drivers of cetacean biodiversity off Angola, and further research into species distribution and environmental parameters should narrow down the habitat preferences for some species in the future. The seasonally variable and transitional oceanographic environment off Angola explains the high cetacean biodiversity recorded relative to most other (solely tropical) ETA countries (Weir 2010a, 2011a).

Classification of Angolan cetacean communities. Some species have wider ecological niches than shown here; for example, blue, fin and sei whales are found in shelf waters in some geographic regions, while right whales and dusky dolphins may also be oceanic. However, the information is based solely on documented occurrence in Angola to date. The species in the grey box are those with the most cosmopolitan distributions. The Risso’s dolphin is included as a temperate species due to additional sightings of this species during survey work offshore of Lobito (Weir unpublished data)

The association of particular cetacean communities with oceanographic biomes means that species diversity in central and southern Angola will fluctuate on a seasonal basis. The Angola-Benguela Front exhibits spatio-temporal variation over the year as the Benguela Current strengthens and weakens, and Weir (2011a) showed corresponding seasonal SST variations of over 7 °C along the Angolan coast. Consequently, species with preferences for cold or tropical waters may shift in distribution northwards or southwards in response to seasonal changes in oceanography.

Environmental parameters also influence the relative abundance of different species in Angolan waters. For example, in the genus Stenella the prevalence of Atlantic spotted dolphins, striped dolphins and Clymene dolphins off Angola in comparison with very few sightings of pantropical and spinner dolphins, may be the result of the productive Benguela-influence. Pantropical spotted and spinner dolphins are more characteristic of tropical oligotrophic waters (Au and Perryman 1985), and are replaced in more productive, slightly cooler areas by the other members of the genus.

The specific use of Angolan waters by some cetacean species also relates to environmental conditions. For example, Cabinda is located in the tropical Gulf of Guinea LME in the far north of Angola, and has consistently warmer SSTs during the winter than further south. This may explain why humpback whale calving and singing behaviour (i.e. breeding activity) has only been confirmed to date in that region of Angola (Best et al. 1999; Cerchio et al. 2014).

Conservation

There are few published accounts of the conservation issues facing cetaceans in Angolan waters, but identified threats in other ETA regions include directed takes (i.e. for human food as ‘marine bushmeat’), bycatch in fishing gear, entanglement, prey reduction due to over-fishing, habitat loss and degradation (including noise disturbance and pollution), vessel strikes, marine ecotourism and live captures for display in aquaria (review by Weir and Pierce 2013).

In 1986, the International Whaling Commission’s moratorium effectively ended commercial whaling in Angolan waters, but there is also evidence for the capture of small cetaceans. Brito and Vieira (2009) found reports of catches of ‘toninhas’ (unidentified dolphins) in Angola between 1940 and 1954 in the national fishing books kept in the National Institute of Statistics in Lisbon, with an average of 20 dolphins landed annually. Those authors considered it likely that bow-riding dolphins were purposefully harpooned by hand for their meat (Brito and Vieira 2009).

There are no specific published records of cetacean fisheries bycatch in Angolan waters, but bycatch affects small cetaceans worldwide and its absence in the literature can be considered a lack of reporting rather than a lack of occurrence in Angola. Weir et al. (2011) reported high numbers of artisanal gillnets deployed in nearshore waters in Namibe Province, and identified them as a major threat to coastal dolphins in the area. Weir and Nicolson (2014) described the potential for bycatch of dolphins during depredation of recreational and commercial fisheries.

Several studies have reported the potential for seismic survey operations to disturb cetaceans in Angola, including spatial avoidance (Weir 2008) and reductions in singing by humpback whales (Cerchio et al. 2014).

The lack of population size information and the absence of quantitative data on impacts on Angolan cetaceans make it impossible to currently assess status and conservation threats. However, the small population of humpback dolphins identified in Namibe Province is clearly of high conservation concern (Weir 2009; Weir et al. 2011), especially given the recent upgrading of the species to Critically Endangered by the IUCN (2018).

Research in Angola: What Next?

Cetacean research in Angola is still in its infancy. Although the species checklist is more complete for Angola than many other ETA countries (Weir 2010a, 2011a), this relates predominantly to MMO data collected during offshore seismic surveys. MMO data can provide information on ‘presence’, species composition and group sizes, but cannot provide robust ‘absence’ data due to the unknown potentially-adverse affects of airgun sound on species occurrence and the fact that sightings often remain unidentified to species level due to the lack of ability to approach animals.

Most survey effort and records of cetaceans to date have originated from the (sub)tropical waters between Luanda and Cabinda, where the oil and gas industry is most active (Weir 2011a, b). With the exception of several short periods of effort (e.g. Axelsen et al. 2004, 2005; Roux et al. 2007; Weir 2009, 2010c), the waters in the southern half of Angola have not been surveyed for cetaceans. Consequently, establishing the year-round species composition, distribution and abundance of cetaceans in the Benguela-influenced region south of Lobito should be a priority for future research, especially since whaling captures and recent sightings indicate that region may be most important for large endangered whales (e.g. blue whale; Figueiredo and Weir 2014).

Information on population sizes, population structure (via genetic sampling), spatio-temporal distribution, movements and diet are required for all cetacean species in Angolan waters. Critical to this is the development of comprehensive ongoing training programmes for local biologists in species identification and techniques such as photo-identification, genetic sampling, necropsying of dead animals and passive acoustic monitoring. In particular the field identification of cetacean species takes significant training and field experience, and building this capacity within Angola will be fundamental to the success of long-term population monitoring.

The collection of quantitative data to assess threats is also highlighted as a research priority, and could be achieved through a trained bycatch observer programme for fishing communities, and monitoring at artisanal and commercial landing sites.

Species priorities for Angolan research include Endangered large whale species (Table 16.2) and the Critically Endangered Atlantic humpback dolphin. A decade has passed since Weir’s (2009) study of humpback dolphins in Namibe Province, and the current status of the species in nearshore waters along the entire coast requires urgent assessment if it is to be conserved in future decades (Weir et al. 2011). Additionally, Angolan waters are potentially of global importance for breeding populations of sperm whale (Weir 2011a, b), and the waters off Cabinda appear to comprise a calving area for humpback whales (Best et al. 1999, Weir 2011a, b, Cerchio et al. 2014). A systematic research programme would be valuable for informing the management of both of those species.

References

Allison C (2016a) IWC summary catch database Version 6.1; Date: 18 July 2016. Available from the International Whaling Commission, Cambridge, UK

Allison C (2016b) IWC individual catch database Version 6.1; Date: 18 July 2016. Available from the International Whaling Commission, Cambridge, UK

Allison C, Smith TD (2004) Progress on the construction of a comprehensive database of twentieth century whaling catches. Paper SC/56/O27 presented to the International Whaling Commission

Au DWK, Perryman WL (1985) Dolphin habitats in the eastern tropical Pacific. Fish Bull 83:623–643

Axelsen BE, Lutuba-Nsilulu H, Zaera D, et al. (2004) Surveys of the fish resources of Angola. Survey of the pelagic resources 28 July–27 August 2004. Cruise Reports Dr Fridtjof Nansen. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/11250/107204

Axelsen BE, Luyeye N, Zaera D et al. (2005) Surveys of the fish resources of Angola. Survey of the pelagic resources 16 July–24 August 2005. Cruise Reports Dr Fridtjof Nansen. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/11250/107244

Best PB (1981) The status of right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) off South Africa, 1969–1979. Investigational Report of the Sea Fisheries Institute, South Africa 123:1–44

Best PB (1990) The 1925 catch of right whales off Angola. Rep Int Whaling Commission 40:381–382

Best PB (1994) A review of the catch statistics for modern whaling in southern Africa, 1908-1930. Reports of the International Whaling Commission 44:467–485

Best PB (1996) Evidence of migration by Bryde’s whales from the offshore population in the Southeast Atlantic. Rep Int Whaling Commission 46:315–322

Best PB (2001) Distribution and population separation of Bryde’s whale Balaenoptera edeni off southern Africa. Mar Ecol Progr Ser 220:277–289

Best PB (2007) Whales and dolphins of the southern African Subregion. Cambridge University Press, Cape Town

Best PB, Abernethy RB (1994) Heaviside’s dolphin Cephalorhynchus heavisidii (Gray, 1828). In: Ridgway SH, Harrison R (eds) Handbook of marine mammals, volume 5, the first book of dolphins. Academic, San Diego, pp 289–310

Best PB, Meÿer MA (2009) Neglected but not forgotten: southern Africa’s dusky dolphins. In: Würsig B, Würsig M (eds) The dusky dolphin: master acrobats off different shores. Elsevier Science & Technology, Oxford, pp 291–312

Best PB, Reeb D, Morais M, et al. (1999) A preliminary investigation of humpback whales off northern Angola. Paper SC/51/CAWS33 presented to the IWC Scientific Committee, 12 pp

Bree PJH v, Purves PE (1972) Remarks on the validity of Delphinus bairdii (Cetacea, Delphinidae). J Mammal 53:372–374

Brito C, Vieira N (2009) Captures of “toninhas” in Angola during the 20th century. Paper SC/61/SM18 presented to the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission, Madeira, Portugal, 2009

Brown SG (1959) Whales observed in the Atlantic Ocean: notes on their distribution. Norsk Hvalfangst-Tidende 48:289–308

Cadenat J (1959) Rapport sur les petits cétacés ouest-africains: résultats des recherches entreprises sur ces animaux juqu’au mois de mars 1959. Bulletin de l’Institut Français D’Afrique Noire Série A, Sciences Naturelles 21:1367–1409

Caldwell DK, Caldwell MC (1989) Pygmy sperm whale Kogia breviceps (de Blainville, 1838): Dwarf sperm whale Kogia sima Owen, 1866. In: Ridgway SH, Harrison R (eds) Handbook of marine mammals, volume 4, river dolphins and the larger toothed whales. Academic, San Diego, pp 235–260

Cerchio S, Collins T, Mashburn S et al. (2010) Acoustic evidence of blue whales and other baleen whale vocalizations off northern Angola. Paper SC/62/SH13 presented to the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission, Agadir, June 2010. 8 pp. (Available from the IWC Secretariat, Cambridge, UK)

Cerchio S, Strindberg S, Collins T et al (2014) Seismic surveys negatively affect humpback whale singing activity off northern Angola. PLoS One 9(3):e86464

Cunha HA, de Castro RL, Secchi ER et al (2015) Molecular and morphological differentiation of common dolphins (Delphinus sp.) in the Southwestern Atlantic: testing the two species hypothesis in sympatry. PLoS One 10(11):e0140251

Davis RW, Ortega-Ortiz JG, Ribic CA et al (2002) Cetacean habitat in the northern oceanic Gulf of Mexico. Deep-Sea Res I Oceanogr Res Pap 49:121–142

Dyer BM (2007) Report on top-predator survey of southern Angola including Ilha dos Tigres, 20–29 November 2005. In Kirkman SP (ed) Final Report of the BCLME (Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem) Project on Top Predators as Biological Indicators of Ecosystem in the BCLME. BCLME Project LMR/EAF/03/02. 381 pp. Available at: http://www.adu.uct.ac.za/adu/projects/sea-shore-birds/communication/report-bclmetpp

Elwen SH, Findlay KP, Kiszka J et al (2011) Cetacean research in the southern African subregion: a review of previous studies and current knowledge. Afr J Mar Sci 33:469–493

Fertl D, Jefferson TA, Moreno IB et al (2003) Distribution of the Clymene dolphin Stenella clymene. Mamm Rev 33:253–271

Figueiredo JM (1960) Pescarias de baleia nas províncias africanas Portuguesas. Boletim da Pesca 66:29–37

Figueiredo I, Weir CR (2014) Blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) off Angola: recent sightings and evaluation of whaling data. Afr J Mar Sci 36(2):269–278

Findlay KP, Best PB, Ross GJB et al (1992) The distribution of small odontocete cetaceans off the coasts of South Africa and Namibia. S Afr J Mar Sci 12:237–270

Griffin M, Coetzee CG (2005) Annotated checklist and provisional national conservation status of Namibian mammals. Technical Reports of Scientific Services No. 4. Directorate of Scientific Services, Ministry of Environment and Tourism, Windhoek, 207 pp

Hamazaki T (2002) Spatiotemporal prediction models of cetacean habitats in the mid-western North Atlantic Ocean (from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, U.S.A. to Nova Scotia, Canada). Mar Mamm Sci 18:920–939

Harmer SF (1928) History of whaling. Proc Linnaean Soc Lond 140:51–95

IUCN (2018) The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2017–3. www.iucnredlist.org. Downloaded on 20 January 2018

Jefferson TA, Curry BE, Leatherwood S et al (1997) Dolphins and porpoises of West Africa: a review of records (Cetacea: Delphinidae, Phocoenidae). Mammalia 61:87–108

Jefferson TA, Weir CR, Anderson RC et al (2013) Global distribution of Risso’s dolphin Grampus griseus: a review and critical evaluation. Mamm Rev 44:56–68

Krakstad J-O, Vaz-Velho F, Axelsen BE et al. (2003) Surveys of the fish resources of Angola. Survey of the pelagic resources 20 July–19 August 2003 (Including observations of marine seabirds and mammals). Cruise Reports Dr Fridtjof Nansen. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/11250/107254

Kramer MO (1961) Dolphins have the laugh on us … as far as speed goes. South African Yachting News 1961:28–30

Leeney RH, Post K, Best PB et al (2013) Pygmy right whale Caperea marginata records from Namibia. Afr J Mar Sci 35(1):133–139

Mackintosh NA (1942) The southern stocks of whalebone whales. Discovery Rep 22:197–300

Mackintosh NA (1965) The stocks of whales. Fishing News (Books) Ltd, London

Macleod CD, Perrin WF, Pitman RL et al (2006) Known and inferred distributions of beaked whale species (Ziphiidae: Cetacea). J Cetacean Res Manag 7(3):271–286

Michalsen K, Alvheim OB, Zaera-Perez D et al. (2015) Surveys of the fish resources of Angola. Cruise Report N0. 8/2015. Surveys of the pelagic fish resources of Angola, 15 August–13 September 2015. Cruise reports Dr. Fridtjof Nansen. EAF—N2015/8. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2374573

Mikhalev JA, Savusin VP, Kishiyan NA et al (1981a) To the problem of the feeding of sperm whales from the Southern Hemisphere. Rep Int Whaling Commission 31:737–745

Mikhalev YA, Ivashin MV, Savusin VP et al (1981b) The distribution and biology of killer whales in the Southern Hemisphere. Rep Int Whaling Commission 31:551–565

Mörzer Bruyns WFJ (1968) Sight records of cetacea belonging to the genus Mesoplodon Gervais, 1850. Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde 33:106–107

Mörzer Bruyns WFJ (1971) Field guide of whales and dolphins. CA Mees, Amsterdam

Olsen Ø (1913) On the external characters and biology of Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera brydei), a new rorqual from the coast of South Africa. Proc Zool Soc Lond 1913:1073–1090

Richards R (2009) Past and present distributions of southern right whales (Eubalaena australis). N Z J Zool 36(4):447–459

Rosenbaum HC, Pomilla C, Mendez M et al (2009) Population structure of humpback whales from their breeding grounds in the South Atlantic and Indian oceans. PLoS One 4(10):e7318

Roux J-P, Dundee BL, da Silva J (2007) Seabirds and marine mammals distributions and patterns of abundance. Chapter 41 in Kirkman, S.P. (ed.) Final report of the BCLME (Benguela Current Large Marine Ecosystem) Project on Top Predators as Biological Indicators of Ecosystem in the BCLME. BCLME Project LMR/EAF/03/02. 381 pp. Available at: http://www.adu.uct.ac.za/adu/projects/sea-shore-birds/communication/report-bclmetpp

Ruud JT (1952) Catches of Bryde-whale off French Equatorial Africa. Norsk Hvalfangst-Tidende 12:662–663

Sherman K (2014) Toward ecosystem-based management (EBM) of the world’s large marine ecosystems during climate change. Environ Dev 11:43–66

Simmons DC (1968) Purse seining off Africa’s west coast. Commer Fish Rev 30:21–22

Smith TD, Reeves RR, Josephson EA et al (2012) Spatial and seasonal distribution of American whaling and whales in the age of sail. PLoS One 7(4):e34905

SMM (2018) Committee on Taxonomy. List of marine mammal species and subspecies, updated 2017. Society for Marine Mammalogy: www.marinemammalscience.org, consulted on 20 January 2018

Spalding MD, Fox HE, Allen GR et al (2007) Marine ecoregions of the world: a bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. Bioscience 57:573–583

Stewart BS, Leatherwood S (1985) Minke whale Balaenoptera acutorostrata Lacépède, 1804. In: Ridgway SH, Harrison R (eds) Handbook of marine mammals, volume 3, the sirenians and baleen whales. Academic, San Diego, pp 91–136

Tønnessen JN, Johnsen AO (1982) The history of modern whaling. University of California Press, Berkeley/Los Angeles

Tormosov DD, Budylenko GA, Sazhinov EG (1980) Biocenoological aspects in the investigations of sea mammals. Paper SC/32/02 presented to the IWC Scientific Committee, July 1980, 9 pp

Townsend CH (1935) The distribution of certain whales as shown by logbook records of American whaleships. Zoologica 19:3–50

Van Waerebeek K (1997) Long-beaked and short-beaked common dolphins sympatric off central-West Africa. Paper SC/49/SM46 presented to the IWC Scientific Committee, October 1997, 4 pp

Van Waerebeek K, Barnett L, Camara A et al (2004) Distribution, status, and biology of the Atlantic humpback dolphin, Sousa teuszii (Kükenthal, 1892). Aquat Mamm 30:56–83

Weir CR (2006a) Sightings of beaked whales (Cetacea: Ziphiidae) including first confirmed Cuvier’s beaked whales Ziphius cavirostris from Angola. Afr J Mar Sci 28:173–175

Weir CR (2006b) Sightings of rough-toothed dolphins (Steno bredanensis) off Angola and Gabon, South-east Atlantic Ocean. Abstracts of the 20th Annual Conference of the European Cetacean Society, Gdynia, Poland, 2–7 April 2006

Weir CR (2006c) First confirmed records of Clymene dolphin Stenella clymene (Gray, 1850) from Angola and Congo, South-East Atlantic Ocean. Afr Zool 41:297–300

Weir CR (2007) Occurrence and distribution of cetaceans off northern Angola, 2004/05. J Cetacean Res Manag 9:225–239

Weir CR (2008) Overt responses of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae), sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus), and Atlantic spotted dolphins (Stenella frontalis) to seismic exploration off Angola. Aquat Mamm 34:71–83

Weir CR (2009) Distribution, behaviour and photo-identification of Atlantic humpback dolphins (Sousa teuszii) off flamingos, Angola. Afr J Mar Sci 31:319–331

Weir CR (2010a) A review of cetacean occurrence in West African waters from the Gulf of Guinea to Angola. Mamm Rev 40:2–39

Weir CR (2010b) First description of Atlantic humpback dolphin (Sousa teuszii) whistles, recorded off Angola. Bioacoustics 19:211–224

Weir CR (2010c) Cetaceans observed in the coastal waters of Namibe Province, Angola, during summer and winter 2008. Mar Biodivers Rec 3:e27

Weir CR (2011a) Ecology and conservation of Cetaceans in the waters between Angola and the Gulf of Guinea, with focus on the Atlantic Humpback Dolphin (Sousa teuszii). PhD thesis, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen

Weir CR (2011b) Distribution and seasonality of cetaceans in tropical waters between Angola and the Gulf of Guinea. Afr J Mar Sci 33:1–15

Weir CR, Coles P (2007) Morphology of common dolphins (Delphinus spp.) photographed off Angola. Abstracts of the 17th Biennial Conference of the Society for Marine Mammalogy, Cape Town, South Africa, 29 November–3 December 2007. Society for Marine Mammalogy, San Diego

Weir CR, Collins T (2015) A review of the geographical distribution and habitat of the Atlantic humpback dolphin (Sousa teuszii). Adv Mar Biol 72:79–117

Weir CR, Nicolson I (2014) Depredation of a sport fishing tournament by rough-toothed dolphins (Steno bredanensis) off Angola. Aquat Mamm 40(3):297–304

Weir CR, Pierce GJ (2013) A review of the human activities impacting cetaceans in the eastern tropical Atlantic. Mammal Rev 43(4):258–274

Weir CR, Debrah J, Ofori-Danson PK et al (2008) Records of Fraser’s dolphin Lagenodelphis hosei Fraser, 1956 from the Gulf of Guinea and Angola. Afr J Mar Sci 30:241–246

Weir CR, Collins T, Carvalho I et al (2010) Killer whales (Orcinus orca) in Angolan and Gulf of Guinea waters, tropical West Africa. J Mar Biol Assoc U K 90:1601–1611

Weir CR, Van Waerebeek K, Jefferson TA et al (2011) West Africa’s Atlantic humpback dolphin (Sousa teuszii): endemic, enigmatic and soon endangered? Afr Zool 46:1–17

Weir CR, MacLeod CD, Pierce GJ (2012) Habitat preferences and evidence for niche partitioning amongst cetaceans in the waters between Gabon and Angola, eastern tropical Atlantic. J Mar Biol Assoc U K 92:1735–1749

Weir CR, Coles P, Ferguson A et al (2014) Clymene dolphins (Stenella clymene) in the eastern tropical Atlantic: distribution, group size, and pigmentation pattern. J Mammal 95(6):1289–1298

Wilson CE, Perrin WF, Gilpatrick JW et al (1987) Summary of worldwide locality records of the striped dolphin, ‘Stenella coeruleoalba’. NOAA-TM-NMFS-SWFC-90. 72 pp

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Weir, C.R. (2019). The Cetaceans (Whales and Dolphins) of Angola. In: Huntley, B., Russo, V., Lages, F., Ferrand, N. (eds) Biodiversity of Angola. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03083-4_16

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03083-4_16

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-03082-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-03083-4

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)