Abstract

For farmers, the transition towards agroecology implies redesigning both their production system and their commercialisation system. To engage in this type of transition, they need to develop new knowledge on practices adapted to local conditions, which will involve new actors in their network. This chapter explores the role of actors’ networks in the agroecological transition of farmers, with a particular focus on farming practices and modes of commercialisation. We held semi-structured interviews to understand: (i) individual farmers’ trajectories of change, considering practices at the farm and food system levels; (ii) the role of farmers’ networks in their involvement in the agroecological transition; and (iii) the role of their networks on a broader scale. In the Tarn-Aveyron basin, we interviewed ten dairy farmers and 50 actors interacting with them in connection with their farming practices. We focus on two dairy farmers’ trajectories: one who took a path towards agroecology, and the other who did not. We then show that the role of actors’ network is crucial in facilitating or impeding the agroecological transition. We highlight the importance of considering actors’ networks as a whole, including in the commercial sector, as having a key role in farmers’ shift towards agroecological transition.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many actors in various spheres are increasingly coming to recognise agroecology as a relevant solution for the environmental and social problems posed by conventional agriculture (Wezel et al. 2009; Altieri et al. 2017). Agroecology is a relatively new concept, and its rise hides significant diverging viewpoints both around the definition of agroecology and how to encourage the agroecological transition (AET) of farming. In France, this rise of agroecology is conveyed by two largely prescriptive discourses. On one hand are the people that highlight all of the virtues of agroecology during the Anthropocene, and namely the inevitability of a solution that must be imposed in view of the problems posed by the conventional model (Vanloqueren and Baret 2009; Wezel et al. 2009). Taking ecological and social issues into account, this consists of recalling and explaining the rationality of the proposal for change, and even calls for increased responsibility with respect to it (Le Foll 2012; Duru et al. 2015). While the majority of actors recommend the combined improvement of economic and environmental performance, some are driving for a deeper transformation in systems, and in particular socio-economic systems (Ryschawy et al. 2015; Sanderson Bellamy and Ioris 2017). On the other hand are actors against agroecology, who seek to point out all of the problems raised by this paradigm shift and to recall the robustness and potential of conventional model solutions, in particular in facing the problem of pollution, via technological advancements such as precision agriculture (Sanderson Bellamy and Ioris 2017). Taking economic issues into account, they seek to disqualify proposals for change, which are judged to be ideas that are far-fetched or from “a few gurus” suspected of returning to the past and relabelling ancestral practices. Opponents of agroecology mention the efforts already made with respect to the complex situations of farms, and highlight technological proposals that are more compatible with “tomorrow’s agriculture” (Bonny 2017). While it is now recognised that the industrial farming model that developed starting in the 1950s enabled agriculture to progress and modernise within a logic of confinement – a laboratory study in which its operation was not verified under real conditions (Aggeri and Hatchuel 2003) –, an increasing amount of research indicates that the organisation of agricultural advising and supply chains as well as the standards associated with them are locking out the transition of agriculture towards other models, in particular agroecology (Vanloqueren and Baret 2009).

These two prescriptive model definitions and the positions of the actors concerned hide a broad diversity of situations within a territory (Therond et al. 2017). In this paper, we hypothesise that the position of numerous actors, and of farmers in particular, remains a hybrid between these two perspectives, in which their involvement in the AET instead takes place through the combination of different exchanges with an evolving social network. To test this hypothesis, we developed a device for analysing the relations between the dynamics at farms and the nature and role of the social networks of the farmers concerned. In this study, we particularly focused on the way that farmers jointly reconfigure their networks and their practices in order to compromise with the uncertainty inherent to the ecologisation of their production system (Girard 2014). To do so, we assume that farmers’ knowledge evolves, with the ecologisation of farming specifically implying hybridising empirical/situated knowledge and scientific/generic knowledge (Chevassus-au-Louis 2007; Duru et al. 2015). Therefore, our work follows research on the analysis of knowledge systems and innovation systems in farming (Klerkx et al. 2010) by focusing on the circulation of information between actors via actors’ networks.

From this viewpoint, our analysis leads us to a better understanding of the nature of the social interrelations determining the transition (or not) of livestock farmers to agroecology , in terms of both agricultural practices and commercialisation practices. We combined two types of approach. Systemic agronomy allowed us to analyse farmers’ trajectories over the long term (Coquil et al. 2013), while the sociology of organised action allowed us to better understand the social interrelations or organisational configurations within which farmers circulated during their trajectory (Crozier and Friedberg 1980). In terms of method, we held semi-structured interviews with a diversity of livestock farmers from the Tarn-Aveyron basin, as well as with the main actors with whom they interacted to design their practices. In this chapter, we present the methodology used and illustrate it by means of the example of two model trajectories of change in the livestock farming practices of farmers in the Tarn-Aveyron basin, and namely a farmer with little engagement in the AET, compared to one who is highly engaged in it. This example shows us how these two trajectories are related to two different types of exchange network . We then zero in our analysis and cross-compare changes in farming practices and changing commercialisation practices. Lastly, we zoom out to a more generic level to draw more general conclusions on the interrelations between actors on the level of the Tarn-Aveyron basin as a territory. To conclude, we discuss these results in light of additional research carried out under the TATA-BOX project.

Methodological Approach Developed

Sampling and Data Collection

In this study our goal was to understand a diversity of positions and roles of actors in the territory of the Tarn-Aveyron basin with respect to the AET. Furthermore, in order not to exclude key elements a priori, we adopted a broad interpretation of agroecology . We drew inspiration from the MAAF’sFootnote 1 political definition of agroecology as a “set of effective practices on the economic and environmental level” (Le Foll 2012) that address ecological issues relating to the food system (Francis et al. 2003). This led us to take into account the perception of consumers and citizens, commercialisation systems for food products and, more generally, the social dimension of agroecology (Wezel et al. 2009; Sanderson Bellamy and Ioris 2017). Acknowledging this broad definition of agroecology, and based on information from local partners of the TATA-BOX project (the chamber of agriculture, cooperatives, etc.), we identified a diversity of livestock farmers in terms of both agricultural practices on the one hand, and commercialisation practices on the other (notion of the ecology of the food system ).

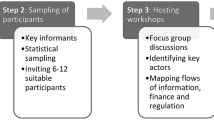

To analyse the relations between dynamics of practices on farms, and social network dynamics, we created an interview device applied over two consecutive years. This device was deployed in three main stages: (1) identification of a diversity of livestock farmers in terms of agroecological practices (farming and commercialisation practices); (2) identification of the actors belonging to their respective social networks via telephone preliminary interviews; and (3) semi-oriented interviews with all of these actors, which we recorded in order to subsequently replay and analyse using an inductive method (Glaser and Strauss 1967).

In the first year we interviewed five farmers, selected according to the gradient of agroecological farming practices on their farm, and in the following year five farmers, according to a gradient of commercialisation practices (Fig. 1). Through this sampling method, we avoided the classic trap of STSoc (science, technology, and society) approaches, which consists in always focusing on the people who are innovative in their field. Instead, we opened up the field of analysis to a broad diversity of actor positions. During interviews with livestock farmers, we chose to start with the question of the farmers’ practices, without assuming what their position with respect to agroecology was, or what constitutes it. We then asked them to tell us the story of their farm to understand the paths taken throughout their trajectory (Coquil et al. 2013; Ryschawy et al. 2013), subsequently asking for clarifications regarding their practices, changes in their values and social networks, and the role of the members of these networks.

Positions of the farmers interviewed. In blue are the farmers interviewed during the 1st year (gradient of farming practices); in orange are the farmers interviewed during the 2nd year (gradient of commercialisation practices, based on the number of intermediaries and social proximity between producers and consumers)

To establish the list of social actors to interview, we used a telephone preliminary interview to ask the ten farmers to identify the main actors in collaboration with whom they designed their practices. As a result, we were able to interview 50 actors from the social networks of the ten livestock farmers selected (23 the first year and 27 the second year). These actors were equally likely to be either classic advisory actors or actors from agricultural supply chains, or else neighbours, spouses, or other territorial actors (tourism, etc.). We asked these actors to detail their role, their relations with the farmer who had mentioned them, and their relations with other actors in the territory (Box 1). The topic of agroecology was addressed only at the end of the interview, so as not to orientate their statements towards farming issues and their role in this dynamic.

Box 1 An Active Learning Process Involving Master’s Students in the Second Half of Their Degree

This research was carried out as part of the “Territorial Engineering ” module of the last year of the agronomic engineering degree at the INP-ENSAT specialising in AGREST: agroecology of the production system in the territory. In the form of a one-month PBL (problem-based learning ) experience, the module allowed students to analyse the strategies and interrelations of actors underpinning the AETs at work in a territory. The educational utility of this work is to turn students into actors of their training by giving them a problem to resolve and supporting them in this process instead of handing them a theory to apply (Raucent et al. 2016). In this PBL, the theoretical elements involved the theoretical and methodological frameworks and the methods available, but not the topic of the AET and the position of the related actors, which are subjects of the analysis (Therond et al. 2010). To carry out their project, the students were supervised by two territorial agronomy researchers (Olivier Therond, INRA UMR AGIR and Julie Ryschawy, INPT ENSAT) and one researcher in the sociology of organised action (Thomas Debril, INRA UMR AGIR). The viewpoints of these two disciplines were combined to integrally cover the agronomic and socio-economic dimensions of the AET of a territory (cf. Fig. 2).

Analysing Farmers’ Past Trajectory of Change to Understand Their Transition

Our retrospective interviews allowed us to understand the long-term strategies of farmers and to identify the various “coherence phases” in which the farm had been engaged over time. These were the phases in which the farmer’s practices were consistent with his or her values and objectives (Coquil et al. 2013). For each phase, we considered the farmer’s objectives and way of thinking. Specific quotes were recorded and linked to technical-economic data on the farm and on the farmer’s practices and commercialization system . This methodology has been adapted from the Sociology of Organized Action (Crozier and Friedberg 1980). It allows us to identify how the evolution of the farmer’s values leads to changes of varying depth in the production system, resulting in a new coherence phase. We were particularly attentive to elements of the socio-economic context (e.g. new supply chains), the agronomic context (e.g. climate, soil erosion), and the influence of the farmer’s social network leading to a transition in the livestock farming system . In particular, meeting with an actor or the dissemination of a piece of information can be key elements in the trajectory of the farmer in question and the path that he or she follows (Ryschawy et al. 2013).

Analysing the Role of the Actors’ Networks in the Transition Towards Agroecological Practices

We used the framework of the sociology of organised action to analyse the interrelations between actors surrounding each livestock farmer and how each actor influences the farmer in his or her values, perspective of the livestock farming system , and/or choice of practices. To understand the role of the actors’ networks, we first analysed the relationships that each farmer had with the actors interviewed, in terms of level of interaction (from once a year to daily), type of interaction (top-down expertise or knowledge exchange) and type of relationships (affinity or conflict). We then built on the same approach to analyse the relationships between actors themselves, and draw conclusions on the broader local network through a stakeholder analysis. Here we considered the involvement of the local actors, for or against agroecology , and the level of each actor’s importance in local farmers’ decisions and transitions in their practices.

Results: Actors’ Networks as Obstacles or Levers to the Agroecological Transition

To present our results on the role of actors’ networks in farmers’ AET, we first present the farmers’ trajectories and their influence on the evolution of these actors’ networks, considering two extreme case studies: a farm that is not at all agroecological, and one that is highly agroecological. We then consider the broader analysis on the Tarn-Aveyron Basin, highlighting that some actors are basically “central” and unavoidable for most farmers. In particular, the actors involved in the commercialisation of inputs and products play a key role. We then focus on the other actors that are “peripheral”, that is, who are not involved in the network of all the livestock farmers studied, but who have a major influence on their transition or not towards agroecology . These actors may be part of the agricultural sector, including researchers and farmers, but are not necessarily so.

Trajectories of Change and Individual Reconfiguration of the Network

Of the ten farmers interviewed, in this paper we have chosen to present the in-depth analysis of one farmer not engaged in the AET (called Mr. CONV) and his network, and then to compare this analysis to that of the trajectory and network of a farmer heavily engaged in the AET (called Mr. AE, for agroecology ).

Configuration I – The Case of Mr. CONV: Agroecology Seen Through the Conventional Lens

Increasing the Coherence of a Model Integrated Throughout the Trajectory

The analysis of the trajectory of change of Mr. CONV (Farmer 1 in Fig. 1), a farmer not engaged in the AET (Fig. 3), shows how his embeddedness within the incumbent sociotechnical regime drives him to continuously and increasingly reinforce a highly segmented innovation logic.

Mr. AE trajectory diagram along time identifying the main coherence phases in his system practices and values and main quotes illustrating his way of thinking. Main important fact influencing his choices are represented below the arrow – adapted from Coquil et al. (2013)

Following the retirement of his parents, who had previously been his business partners, Mr. CONV continued farming with Prim’Holstein dairy cows, managing on his own a herd of 45 lactating animals on 72 ha, with a quota of approximately 300,000 litres of milk. According to certain farming technicians, “his system [was] stable and produce[d] good-quality milk”. At the time, Mr. CONV’s goal was to operate based on a logic of maximising milk production, typical of the “Colbertist” integrated system (Chevassus-au-Louis 2007; Girard 2014). He farmed maize and straw cereals (wheat and barley) to complete the fodder ration (which advisers also considered to be of good quality). Things really took off when he started to organise the arrival on the farm of his son, who had previously been involved only occasionally, during his studies. At the time, the innovation logic retained for the farm’s future was to increase the volume of milk: this was followed by an increase in the herd to 60 cows. Therefore, his main goal would be to optimise his production tool to achieve the least expensive milk production possible and therefore to be competitive on large markets. Mr. CONV was therefore operating on the basis of a “technicist” logic advanced by the dominant sociotechnical regime (Plumecocq et al. 2018).

In 2013 his son graduated and started working with his father full-time. Starting in 2015, the construction of a high-tech building and the installation of milking robots – both of which entailed huge costs – were hindered by accidents and mistakes by the workers. These choices led to a delicate financial situation which could have caused the system to go bankrupt or triggered a change of logic. This marked a new stage characterised by a significant reorganisation of the work, as they implemented a third daily milking round in order to produce more milk per day and to pay off their investments. This reorganisation maintained the objective of optimising milk production, as Mr. CONV emphasises: “The investment is done, so now to pay off the expenses!”. This was a strategic decision that at the time allowed him to produce 10–15% more milk, that is, 400,000 litres of milk.

Mr. CONV prefers to purchase proteins and cereals rather than producing them on his lands, and does not seek nutritional autonomy that would limit his production levels. In parallel, the management of farmed areas, and in particular maize and cereal ensilage, are entrusted to an independent contractor: “Today, the less we work on the land, the better things go”. While the volume of milk has effectively increased and expenses have somewhat decreased, the farm is still subject to heavy debt payments. This handicap makes the bank reluctant to provide the new loans necessary for establishing his son and implementing his plans. According to him, “problem number one today is the banks”. The success of this undertaking, that many consider to be highly ambitious, depends on this lock-in. Even so, Mr. CONV and his son appear sure of their goals and are working towards them; they do not want to hear about agroecology, and consider “that today, the priority is to provide for everyone”.

Analysis of the Network of Mr. CONV and His Son: A Top-Down Network to Enable Real Technical Optimisation of the Dairy Workshop

These changes in Mr. CONV’s trajectory resulted in an evolution in his network of actors, which progressively became more coherent with his innovation logic and his segmented-by-workshop perspective of his system (Fig. 4). By increasing milk production, Mr. CONV is following the same logic as one of his advisers, financed by his cooperative to help optimise production: “It’s the volume of milk that enables you to pay the bills”. This logic echoes that of the Sodiaal cooperative, to which he delivers his milk, because it transforms most of the milk that it collects into dairy products that it sells at purchasing hubs. These hubs are particularly sensitive to prices and largely determine the choices of local livestock farmers, although they do not necessarily prioritise local markets. Based on this “volume logic”, Mr. CONV applies a strategy that is highly segmented by workshop, and to do so, surrounds himself with dairy production advisers, more or less automatically applying their logic as recommended by an “expert” council. He describes their advice above all as “technical”. In addition, the genetic selection expert emphasises that “the breed of dairy cows is designed to produce inexpensive milk in large quantities”. All the advisers agree on the fact that agroecology does not appear relevant for overcoming challenges in the global food supply, stressing that “[i]n the majority of cases, it’s more worthwhile to buy a bit of soy cake so as to produce more milk with the cows”. This logic is also apparent in the purchasing of high-quality feed and the establishment of very specific rations to optimise production levels per cow and to limit waste. In July 2014, Mr. CONV delved even deeper into this logic: he stopped using the technical support of the dairy management agency, which he considered not to be sufficiently effective, and sought out the services of an independent nutritionist outside of the typical conventional network. Even more technical than the others, the nutritionist noted a key element in the trust that Mr. CONV put in him: “I can establish rations practically to the gram of digestible protein”, thus helping him to determine optimised and therefore less expensive rations based on co-products.

Mr. CONV or the Limits of “Conventional” Advisory Services of the Dominant Sociotechnical Model

Mr. CONV’s dynamic is supported and strengthened by the other actors. His network is driving him to continue even further down the path of the technicist paradigm and to completely exclude any AET. Comments by the adviser from the cooperative (“if somebody tells you about feed self-sufficiency, they’re out of touch with reality! It’s just a big fad.”) and the independent nutritionist (“if agroecology means planting three trees in the middle of a cereal field, it’s a joke”) attest to this. This prescriptive approach creates value assessment devices that rank practices and clearly depict “technical” progress as being the optimisation of productivity associated with technological innovation (Plumecocq et al. 2018). For example, Mr. CONV emphasises that his independent nutritionist “is a part of the networks where it feels like people want to make progress”. These cognitive and normative frameworks carry weight in knowledge and influence the individual practices of livestock farmers, simultaneously playing a role in the reproduction of the norms of the dominant sociotechnical regime (van der Ploeg et al. 2009; Klerkx et al. 2010). Yet Mr. CONV no longer truly trusts the “experts” of the conventional model, because they do not go far enough. He stresses moreover that advisers “are incapable of leading groups” and that “[i]f all of the dairy management agencies in France were highly competent, our job wouldn’t exist”. As Chiffoleau (2009) points out, the analysis of Mr. CONV’s network allows us to see who the real “experts” are. He nevertheless seeks out other sources, in this case the independent nutritionist with whom he has developed a horizontal relationship, which tends to be more usual in a agroecological model in the sense of Altieri et al. (2017).

Configuration II: The Case of Mr. AE: Agroecological Intensification as a Form of Hybridisation

Mr. AE is strongly engaged in the AET in terms of farming practices (Farmer 4 in Fig. 1). The Fig. 5 allows us to see how he is changing the actors in his network, along with his transition towards agroecology . He will limit involvement with actors that prevent him from transitioning towards agroecology, and bring in new actors that will facilitate the transition.

Mr. AE trajectory diagram along time identifying the main coherence phases in his system practices and values and main quotes illustrating his way of thinking. Main important facts influencing his choices are represented below the arrow. – adapted from Coquil et al. (2013)

The Coherence of an Agroecological Model: A Trajectory Towards Technical and Decision-Making Autonomy

Mr. AE is a member of the Groupe agricole d’exploitation en commun (GAEC, joint agricultural group) established by his father in 1985. The 40-ha farm of his UAA produced 300,000 litres of milk with 45 Prim’Holstein dairy cows. The system was managed conventionally, with a large proportion of irrigated maize, among other crops. In 1999, Mr. AE purchased a neighbouring farm and thus increased his UAA to 88 ha. In 2005, following his father’s retirement, he tried to team up with someone in the GAEC with whom he had no family connection, but this person left the farm after 6 months. Under pressure from the MSA (the agricultural social mutual society), Mr. AE chose to switch to the legal status of an EARL. In 2009, he gave it “one last shot” after losing €18,000 when the price of milk dropped to €270/t and cereals to €100/t, despite the heavy workload its production entailed. As he explains today, “I was considering stopping everything because I’d run into a dead end”, and started to sell some of his livestock. After consulting with the organic agriculture adviser at the Chamber of Agriculture, he chose to embark on organic production, and explained the new logic underpinning his change of approach: “We’re going to be much more focused on quality before looking for quantity”.

On 1 November 2010, he started the conversion of his livestock and crop farming. The first delivery of organic milk was on 1 January 2013, but his crops were still sold conventionally at the time. As he progressed through the stages of his conversion to organic, Mr. AE took various training programs (homeopathy in 2005, management of plant coverage and intercropping in 2010, bioindicator plants in 2013, large-scale organic cropping in 2014, artificial insemination planned for 2015) and joined the organic dairy farmers’ association of Aveyron. All of this reflects the significant change in his reasoning: “When you’re totally goal-oriented and see nothing else, you’re not going to go take a class”. Since the conversion and thanks to this training, he is gradually trying to improve his system by implementing new tests, such as a recent combination of maize/soy to ensile, to ensure his protein autonomy over the long term: “It takes five years to get the same yields as conventional farms. You can’t put pressure on yourself. The limit is ourselves; there’s a technical change taking place. You can’t become good in every respect overnight”.

At one stage he attempted to cross a Brown Swiss bull with his Prim’Holstein cows to improve his milk production (protein and fat content) before switching to insemination, which he carries out himself. His intention is to be able to pass down the farm (hopefully to his son) and to have good working conditions, by diversifying the crops a little more. His way of going about things fits quite well with agroecology : organic production combined with simplified cropping techniques (SCT), permanent ground coverage (plant coverage and intermediate crops, seeding under coverage), and good rotation management, all the while seeking increasingly advanced autonomy. Ploughing is however still necessary to turn over coverage without using glyphosate. The major change in his innovation logic is the fact of having switched to a systematic perspective encompassing both production workshops – plant and dairy – in conjunction with one another. For example, he considers livestock farming as a means of ensuring an outlet for his plant production, even when there is a problem with them: “whether it works or not, if it doesn’t work, we ensile it!”. Feed self-sufficiency has become a key objective, because it is a way of reducing production costs by shielding oneself from market prices, which are very high and variable from one year to another: “in organic, it stays regular, and that’s really nice”. Limiting investments limits the financial risks that he had faced in the past: “I won’t say that we make a lot more money, but we spend a lot less, so when things go wrong it’s a lot less serious ”.

Analysis of Mr. AE’s Network: Horizontalisation of Practices But no Changes in Terms of Commercialisation

Mr. AE’s trajectory is marked by increasing embeddedness in peer learning networks, which has allowed him to acquire the knowledge to implement agroecological innovations (Fig. 5). The conversion to organic has allowed him to change his perspective, and to produce less while stabilising his income. In terms of production, the top-down recipe of mechanisation is not the only approach; there is also exchange between peers. Regarding his conservation agriculture network, Mr. AE explains that “[i]t’s a great technique; those guys are really passionate”. However, this new network is not his only source of innovation. Mr. AE also innovates in close collaboration with his adviser at the Chamber of Agriculture, who set up the group of livestock farmers with whom he is working to achieve more feed self-sufficiency and to prepare his organic transition. This adviser, despite being an employee of a structure belonging to the dominant sociotechnical regime, has a perspective that is based firmly on knowledge exchange between peers: “Our philosophy is to make farming autonomous” or “Among organic or SCT farmers, we find the same state of mind, that they want to try out other things”. For example, Mr. AE is working towards autonomy and is substantially reducing his number of suppliers: “In terms of suppliers, they’ve been reduced significantly. In reality, we’re a lot more autonomous”. Mr. AE has thus switched to a systemic perspective, a long-term innovation logic, and a rather negative view of the conventional farming network of actors of the dominant sociotechnical regime: “It’s true that switching to organic makes you realise that there’s something wrong with the system. You let yourself be had and you didn’t even realise it”. Despite everything, Mr. AE remains highly critical of the new “agroecological” practices : “Simplified cropping techniques, yeah, but the materials haven’t been simplified…”.

In terms of commercialisation , Mr. AE has not modified his system and actors’ network (Fig. 6): he took advantage of the opportunity for a new organic milk market offered by his cooperative, Sodiaal (the same one as Mr. CONV). The milk produced will be transformed into powder at a factory in Montauban and shipped to China.

Mr. AE: A Hybrid Farmer Who Moderates Two Caricatures of Agroecology

During his transition , Mr. AE needed to acquire new knowledge, especially on grass management. As also emphasised by Farmer 6, “it’s not obvious; you have to relearn how to manage grass”. To do so, Mr. AE adopted a knowledge-sharing and peer-knowledge exchange logic. The idea was to produce the “horizontal” knowledge recognised as being necessary for the development of agroecology, as the adviser from the Chamber of Agriculture pointed out: “We try to address farmers’ worries”; “For it to work, you have to really listen to farmers”; “You have to keep an open ear and make the best of opportunities”. The fact that this adviser belongs to a prominent structure in the dominant sociotechnical system does not ultimately prevent him from becoming a part of this horizontal dynamic of knowledge production and innovations. Ultimately, Mr. AE’s trajectory allows us to nuance a caricatural representation that often sets agroecology and modernity against each other. Mr. AE remains a “technical” farmer in the meaning ascribed by the dominant system, all the while adopting the principles and practices of agroecology. This is supported by Bonny’s argument (2017) that technology should not systematically be seen as an opposite of agroecology. By using the example of this farmer, we demonstrate that technological progress can be a tool that contributes to agroecology, in its definition as combinations of practices that are useful in promoting productivity and respect for the environment. In this sense, agroecology can be seen as a “modern” concept in which nature is used to contribute to the needs of human beings with two clearly separate categories, in the sense of Latour (2006).

The agroecology implemented on Mr. AE’s farm appears to largely follow a productivist logic in terms of markets. Specifically, Mr. AE’s commercialisation practices relate to the opening of a new market for organic powdered milk in China by the SODIAAL cooperative. The support of farmers in their organic conversion by the Chamber of Agriculture of Aveyron in order to supply this market plays a role in intensifying production that is commercialised by conventional actors. However, Mr. AE mentions “that [he] would prefer to sell on short supply chains, but the excessively low demand forces [him] to stay on long chains”. It has turned out to be simpler to retain this historical farm model with collection by the local cooperative. Therefore, contrary to many ideas and as Therond et al. (2017) have emphasised, agroecological farming practices do not necessarily go hand-in-hand with short supply chains, and reciprocally, as we will show through the five farmers studied, are located along a gradient of commercialisation practices.

Agroecological Practices and Food Systems: Zooming in on the Case of Commercialisation Practices

The second year of our study allowed us to explore the supposedly classic link between agroecological farming practices and agroecological commercialisation practices. We found that both the actors supporting farmers in the commercialisation process, and consumers, allowed farmers to move away from the highly divisive notion of the “technical” and to open a much broader field of action for change. With farmers 8, 9, and 10, consumers or actors in direct sale have become new intermediaries, as emphasised by one farmer, a friend of farmer 9, who has his own cutting plant and is a member of a producer store (“you have to bring quality products to consumers. There’s no point in producing just to produce”) or livestock farmer 10, who sells directly, at her farm or at markets (“contact with the consumer is a good way to learn”). These examples clearly demonstrate a broadening of the perspective of the system and of the role of agricultural production in relation to the requests and expectations of consumers. In this way, these interactions between farmers and consumers can lead farmers to move beyond a production system-centred approach, to instead adopt a more all-encompassing consideration of food system issues (Francis et al. 2003; Plumecocq et al. 2018).

Concerning actors of the incumbent sociotechnical regime, Bonneuil and Joly (2013) discuss the neoliberal knowledge production regime. This converges with the ideas of Vanloqueren and Barret (2009), who argue that science in the way that it is currently conducted – in other words, strongly marked by hypothetical and deductive elements, technical standards, and optimisation goals – is locking out the AET. Given that the work of advising and development actors is also underpinned by this logic, it follows that other “niche” actors (according to Schot and Geels (2007)) would be necessary to make the dominant regime evolve.

We therefore found that conversely to Mr. AE’s strategy, another strategy for producers was to establish a small cooperative (30 livestock farmers) on the local scale (three Départements; FADN NUTS III, http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/rica/) to once again take charge of milk commercialisation and price setting modalities, in quest of greater stability and fairer financial compensation. As highlighted by livestock farmer 8, a member of the cooperative, “[w]e trust consumers to choose the right product”.

This involves the creation of a niche market by making use of the image of a local product sold by livestock farmers themselves or at supermarkets where they carry out demonstrations to explain their method. These demonstrations foster trust, as indicated by a manager: “Going even further than that would mean getting intimate with people. If the calves have received medals, the cows are good, and the farm is clean, I trust that”. The quality of the product offered is also an essential point in this strategy and is backed by a set of technical specifications shared by all the producers. Because the specifications are not very restrictive, certain livestock farmers give priority to practices that are similar to the organic specifications (grazing, no antibiotic administration, autonomous feeding at the farm, etc.), but the majority remain very close to conventional livestock farming, with one noteworthy exception, as mentioned by the president of the cooperative: “There’s something else that could be put on the packages as well [other than cows] and that nobody includes, even those that could include it: that it’s ‘GMO-free’”. Contrary to what could be expected from an agroecological method at a human-scale cooperative, there is no exchange between producers around agricultural practices, as emphasised by farmer 8: “no, it’s true that we don’t visit each other’s farms”.

Another strategy observed consists of transforming milk oneself and commercialising production via short supply chain networks. The logic in this case is no longer to offer an inexpensive product to consumers, but to target consumer satisfaction through a local quality product and social interaction (Therond et al. 2017; Plumecocq et al. 2018). Farmer 10 is an example of 100% direct sale commercialisation: “when a customer tells me that they liked it, that it was good, that’s how they pay me”, in other words, their recognition and satisfaction are more important than money. Value is extracted from milk volumes and quality by transforming the milk into cheese or yoghurt. As a sales adviser at the Aveyron Chamber of Agriculture pointed out, “overall, they find each other. It makes it more work for them, but they’re aware that they’re not forced to use long supply chains. And they’re often happy people, joyful people, entrepreneurs, creators”. Reducing the number of intermediaries assures a higher price set by the producers themselves. Yet this process implies know-how and the resulting additional time working, that can be included in the final price of products. Processing is not necessarily an easy stage to carry out, but the Chamber of Agriculture is organised to support this type of strategy through advisory and training services, and according to it, this support goes far beyond technical aspects: “Behind it, I involve people, a pathway, problems, solutions to the problems… ultimately, I put a whole story behind it all”. We observed that in this type of direct commercialisation strategy, some of the milk is often not transformed, and remains sold on long commercialisation supply chains, which enables a compromise providing security as opposed to absolute dissociation from large-scale dairy corporations (Therond et al. 2017). Ultimately, the risk of this type of approach resides in exclusion from the local agricultural network, as a colleague of farmer 4 pointed out (“we were quickly marginalised as soon as we set off in that direction”), even though the members of the network of producers sharing these direct sale tendencies do support one another (“there’s a lot of mutual help, fortunately, otherwise we wouldn’t make it ”).

The Influence of Actor Interrelations on the Agroecological Transition in the Tarn-Aveyron Basin

The main conclusions presented above, based on our cross-analysis of the ten livestock farmers retained and their networks, allowed us to construct a stakeholder analysis of the role of actors in the AET (Fig. 7). This approach allows us to consider the actors interviewed as regards their involvement in favour of agroecology and their influence on local farmers. In Fig. 7, the actors in favour of agroecology are highlighted in green, whereas those against it are highlighted in red.

Central Actors Are Difficult to Avoid and Not Always in Favour of the AET

Another representation of the network allowed us to consider the level and type of interactions and the types of relationships between all actors (Fig. 8). Applying this framework to the five farmers on a gradient of agricultural practices, we noted that some actors were “central”, that is, difficult to avoid as they were in contact with all the farmers interviewed. The actors in the pink circle are considered to be “central” actors with whom all farmers interact for purchasing inputs or commercialisation. The actors in the yellow circle are “peripheral” actors who are specific to each farmer, depending on his or her personal stance with regard to agroecology. This helped us to understand the contrasting perspectives on agroecology and the actions linked to them. For instance, Mr. CONV (Farmer 1) is interacting only with actors in red, as “peripheral actors”, whereas Mr. AE (Farmer 4) is interacting with more green actors who are in favour of agroecology , as “peripheral” actors , even though he is still connecting to red central actors through his commercialisation practices. We found that “central” actors play a key role in farmers’ decisions, even if they are not necessarily in favour of agroecology. We illustrate this specifically for each central actor highlighted.

Local actors’ networks of the farmers interviewed, along a gradient of agricultural practices. The farmers studied are represented in the green circle. The light green areas represent a low level of involvement in agroecology and the dark green areas a strong one. The actors in favour of agroecology are indicated in green, whereas those against it are indicated in red. The actors in the pink circle are considered to be “central” actors , with whom all farmers interact when it comes to purchasing inputs or commercialisation. The actors in the yellow circle are “peripheral” actors , who are specific to each farmer, depending on his or her personal stance towards agroecology. This figure is not intended to be exhaustive; it presents a summary of the results of the five interviews carried out with the dairy farmers and the 27 interviews carried out with the main actors in their professional network within the Tarn-Aveyron territory. Only the major relationships which the farmers claimed had played a role in the adoption of new practices are represented here; other relationships may exist but are not considered central in farmers’ decisions. The network analysis revealed the points of divergence between the different types of farmers, which are partially detailed below

This broader analysis based on the interviews with the ten farmers and their network shows that all of the farmers studied have varying degrees of contact with the Chamber of Agriculture, agricultural suppliers, and farmers’ organisations. These three types of actors have a strong influence on the operation of these farms, because they are linked to a large number of farmers, who are relatively attentive to the advice given or who easily become involved in these structures. Therefore, the Chamber of Agriculture currently has a significant weight in the AET, particularly in the case of the advisers of the mission agriculture biologique (organic farming task force). These advisers encourage horizontal knowledge exchange groups and agroecological farming practices, such as returning to grazing rather than using inputs. Veterinarians also have much potential for making practices evolve or even transforming them, moving towards decreased antibiotic use, by using food as a preventive measure, for example.

Despite being highly influential, agricultural suppliers, which are located upstream from farms, appear to be resisting the change of practices. Their main goal is to uphold the incumbent sociotechnical regime in order to continue to sell products and make a profit from them, with advice targeted by product and not on the “system” scale. There are nevertheless exceptions to this, such as an adviser from Euro Phyto, who offers a broad range of “alternative” products with holistic advice on their use on the farm. In practice, these products are useful only within a holistic approach, as this adviser recommends reducing chemical prophylaxis and promises autonomy for farms.

Concerning milk commercialisation, the most widespread strategy is to sell all of one’s production to a single collector, such as Lactalis or SODIAAL. This involves a contract between the producer and collector to set the milk price in relation to global market prices. Producers are thus left defenceless with respect to prices and the future of their milk. As we have shown, the main room for manoeuvre is found in increasing the volume of milk produced to reduce expenses per production unit and/or try to significantly decrease expenses via a more profound change in the system. The farmers nevertheless remain highly critical of these large corporations, such as farmer 7, who converted to organic for Sodiaal: “because there’s the farmer and then there’s the vultures. You can’t have a conversation with the people at Lactalis. It’s a multinational; it’s a really particular mindset”; or a livestock farmer who commercialises only on short supply chains: “Sodiaal is only a cooperative in name”; “they’re not interested in little niches”.

Actors Called “Peripheral” Yet Essential in Changing Practices

Figure 8 shows that “peripheral” actors may favour agroecology even if they are not in contact with a large majority of farmers locally. The farmers engaged in an AET seek out alternative advising actors, such as CIVAM (rural environment and farming development initiative centres), as well as exchange between peers via farmers’ associations, as one of the farmers noted: “when you stay in your bubble, you always think you’re the best, and when you step out of it, you tell yourself, ‘oh, that’s not working,’ and that opens up your mind a bit”. Exchange between peers also takes place informally by observing trial and error at neighbours’ farms, which is essential for convincing people: “I think that my neighbours are going to watch me, to see if it works, and then if it works, they’ll change” (cf. Box 2). These new exchanges are essential in limiting the isolation phenomenon, as a conventional farming technician pointed out: “you feel isolated when you do direct seeding farming. It’s not the most popular trend”. However, it is important to note that even though these farmers seek new sources of knowledge and experience, they are never completely dissociated from central actors , in particular those in commercialisation. In other words, the networks of these farmers are hybrid: they are based on actors in the dominant sociotechnical system as well as those of innovation niches .

Box 2 The SERACC Network (Services de Régulation en Agricultures de Conservation et Conventionnelle) as an Example of Knowledge Exchange Between Scientists and Farmers

From 2013 to 2016, INRA Toulouse ran a PhD research project based on scientific and empirical knowledge exchange. In contact with farmers’ associations that had undertaken empirical experiments and knowledge transfer on conservation agriculture, we identified specific needs from scientific research that could complement farmers’ knowledge. Ecosystem functions and subsequent services that could benefit farmers were strongly acknowledged by producers engaged in conservation agriculture, but they lacked the tools and ecological expertise to assess the impact of their practices on them. Such agroecological experiments are moreover ill-suited to classical experimental platforms (often with short-term oligo-factorial experimental design) that allow for an exhaustive scientific comprehension of some of the processes involved, but which are far from farmers’ expectations related to multifactorial and local features. It was thus decided that the project would be designed for farmers and with farmers. Fifty-four farmers engaged in the project, forming a network later called the SERACC network, each dedicated one of their own fields (1–1.5 ha) to the study for two growing seasons. Thirty-five of them were members of associations (21 from Sol et Eau en Ségala, 4 from Association Occitane de Conservation des sols, 2 from Groupement des Agriculteurs Bio du Gers, 5 from Agro d’Oc and 3 from Groupement des Agriculteurs de la Gascogne Toulousaine) with a gradual involvement in conservation and/or organic agricultures, while the remaining 19 were neighbouring farmers with more classical practices with regard to tillage and the non-use of cover crops or diversified rotation, for instance. To benefit from this wide diversity of systems, most of the decisions concerning cropping practices on the experimental field were left to the farmer, yet were closely monitored, and only a few restrictions were requested for the purposes of the experiment (crop cultivars and seeds’ origin were identical for all farms and non-organic farmers had to leave an untreated area in their fields). Such design benefited from farmers’ experience and knowledge, as well as ecological equilibria that can only be achieved in systems implemented in the long run. For farmers, this design allowed them: (i) to be actively involved in a research program; (ii) to have direct feedback from science with data explicitly related to their farm and practices; and (iii) to have access to comparative data from local farms with contrasting practices.

As we saw by illustrating the trajectories of farmers 7–10, the system can be unlocked by listening to actors other than those in the agricultural sector in the strict sense. They can be the actors supporting these agricultural actors in order to make their commercialisation practices evolve, but also actors in tourism (restaurateurs, cutlers, etc.), regional nature reserves or numerous environmental associations, or consumers outside of the agricultural environment (Box 3 –Beudou et al. 2017).

Box 3 Cultural and Territorial Vitality Services Play a Key Role in Livestock Agroecological Transition in France

In France, researchers and public policy makers are calling for the agroecological transition of livestock farming. This transition is facing technical, economic, social, and cultural obstacles. Whereas technical obstacles are studied extensively, other categories are receiving very little attention despite their potential role in this respect. This article analyses the livestock cultural and territorial vitality (dis)services (or negative impacts) perceived by local actors on two distinct French territories and understand how these services could act as levers for the AET of livestock. To do so, we interviewed 45 local actors from the livestock sector and local rural development in two French territories: Aubrac (24) and Pays de Rennes (21). We considered mainly farmers, advisors and supply chain actors, but also granted specific importance to local actors not in the agricultural sector (tourism, environment, gastronomy). We conducted inductive content analyses to draw on interviewees’ perceptions and to link the cultural and territorial vitality services identified, to the AET of livestock.

Our work revealed 20 cultural and territorial vitality services, including the nurturing of social bonds and the creation of rural jobs, that can be organized into 11 categories (seven categories of cultural services and four categories of territorial vitality services). Among the 11 cultural services, cultural landscapes linked to livestock and gastronomy heritage were the most cited. Among the nine territorial vitality services, the contribution to social bonds on the territories was the most cited. Here, we show for the first time that the prioritisation of cultural and territorial vitality services differed between the territories studied. Emblematic cattle breeds, food know-how, and quality products were more important in Aubrac, whereas territorial vitality services such as on-farm jobs and social bonds linked to livestock were more cited in the Pays de Rennes. This methodological approach allowed us to highlight and prioritise the different cultural and vitality services that need to be supported by public policy and translated into action. Furthermore, the main findings of this study allowed us to highlight the importance of taking into account the point of view of actors that are not from the agricultural sector and that act in favour of or against the AET.

Conclusion

This study has highlighted the importance of studying actors’ networks if we are to gain an in-depth understanding of the levers or lock-in underlying the decisions of farmers to change (or not) towards agroecology. We have suggested that agricultural practices toward agroecology are not necessarily linked to agroecological practices in terms of commercialisation. There is a need to consider the entire actors’ network, including the agricultural sector and the other sectors, as playing a key role in farmers’ AET. The actors with whom the farmers in our study were discussing their practices were not the same for agricultural practices and commercialisation – which could contribute to explaining such findings. We have also highlighted the fact that actors can act in favour or against AET with no regard for their influence on farmers through a stakeholder analysis . Enterprises commercializing inputs were, in particular, shown to develop barriers to agroecological practices , as they were opposed to autonomy in inputs.

Our analysis has shown that farmers were mostly hybrids on a gradient towards agroecology , who might rely to a greater or lesser extent on technology. This is linked to a hybridisation in the types of advice/exchange they get and the types of actors they include in their network. There is heavy emphasis on “central” actors , including all the farmers’ networks studied, even if they were developing relationships with other specific “peripheral” actors , to develop specific practices.

The method we developed could be applied as a first step to understand the local context before implementing participative conception process. With whom should one work? What are their knowledge and motivations? What are the conflicts, power games or, on the contrary, affinities when it comes to working together? Who are the real experts to be considered? Are they official? Who are the actors excluded from the network? In line with Chiffoleau (2009), we consider that network analysis is a basis to develop participative work with local actors, and to highlight power games. Such results are also useful for policy makers, as they show that networks are more hybrids and evolving than supposed, and have a large impact on the AET. In line with Klerkx et al. (2010), we think this type of study highlights the need for policies that take the adaptiveness of innovation networks into consideration more.

Notes

- 1.

Ministry of Agriculture and Agri-Food and Forest.

References

Aggeri F, Hatchuel A (2003) Ordres socio-économiques et polarisation de la recherche dans l’agriculture: pour une critique des rapports science/société. Sociol Trav 45:113–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0296(02)01308-0

Altieri MA, Nicholls CI, Montalba R (2017) Technological approaches to sustainable agriculture at a crossroads: an agroecological perspective. Sustainability 9:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9030349

Beudou J, Martin G, Ryschawy J (2017) Cultural and territorial vitality services play a key role in livestock agroecological transition in France. Agron Sustain Dev 37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-017-0436-8

Bonneuil C, Joly PB (2013) Sciences, techniques et société. La Découverte, Paris

Bonny S (2017) High-tech agriculture or agroecology for tomorrow’s agriculture? Harvard Coll Rev Environ Soc 4:28–34

Chevassus-au-Louis B (2007) L’analyse des risques. L’expert, le décideur et le citoyen. éditions Quae

Chiffoleau Y (2009) La sociologie des réseaux au service d’une recherche engagée : Retour sur un travail d’équipe en viticulture languedocienne. In: Beguin P (Directeur), Cerf M (eds) Dynamique des savoirs, dynamique des changements, Collection. Toulouse, France, pp 111–127

Coquil X, Lusson JM, Beguin P, Dedieu B (2013) Itinéraires vers des systèmes autonomes et économes en intrants: motivations, transition, apprentissages. In: 20eme Rencontres Recherches Ruminants. Paris, France, pp 1–4

Crozier M, Friedberg E (1980) Actors and systems: the politics of collective action. University of Chicago Press (first published in 1977)., Chicago

Duru M, Therond O, Fares M (2015) Designing agroecological transitions; a review. Agron Sustain Dev 35:1237–1257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-015-0318-x

Francis CA, Lieblein G, Gliessman SR et al (2003) Agroecology: the ecology of food systems. J Sustain Agric 22:99–118. https://doi.org/10.1300/J064v22n03_10

Girard N (2014) Quels sont les nouveaux enjeux de gestion des connaissances ? » L’exemple de la transition écologique des systèmes agricoles. Rev Int Psychosociologie Gest des Comport Organ XIX:51–78. doi: https://doi.org/10.3917/rips.049.0049

Glaser BG, Strauss AL (1967) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter, Hawthorne

Klerkx L, Aarts N, Leeuwis C (2010) Adaptive management in agricultural innovation systems: the interactions between innovation networks and their environment. Agric Syst 103:390–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2010.03.012

Latour B (2006) Nous n’avons jamais été modernes, Essai d’anthropologie symétrique, La Découve. Paris, France

Le Foll S (2012) La première graine, Calmann-Lé. Paris, France

Plumecocq G, Debril T, Duru M et al (2018) The plurality of values in sustainable agriculture models: diverse lock-in and coevolution patterns. Ecol Soc 23. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09881-230121

Raucent B, Milgrom E, Romano C (2016) Guide pratique pour une pédagogie active – Les APP… Apprentissages par Problèmes et par Projets

Ryschawy J, Choisis N, Choisis JP, Gibon A (2013) Paths to last in mixed crop-livestock farming: lessons from an assessment of farm trajectories of change. Animal 7:673–681

Ryschawy J, Debril T, Sarthou JP, Therond O (2015) Agriculture, jeux d’acteurs et transition écologique. Première approche dans le bassin Tarn-Aveyron. Fourrages:143–148

Sanderson Bellamy A, Ioris A (2017) Addressing the knowledge gaps in agroecology and identifying guiding principles for transforming conventional Agri-food systems. Sustainability 9:330. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9030330

Schot J, Geels FW (2007) Niches in evolutionary theories of technical change. J Evol Econ 17:605–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-007-0057-5

Therond O, Paillard D, Bergez JE, et al (2010) From farm, landscape and territory analysis to scenario exercise: an educational programme on participatory integrated analysis. In: 9th European IFSA symposium, building sustainable rural futures: the added value of systems approaches in times of change and uncertainty, 4–7 july 2010, Vienna, Austria, pp 2206–2216

Therond O, Duru M, Roger-Estrade J, Richard G (2017) A new analytical framework of farming system and agriculture model diversities. A review. Agron Sustain Dev 37:21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-017-0429-7

van der Ploeg JDD, Laurent C, Blondeau F, Bonnafous P (2009) Farm diversity, classification schemes and multifunctionality. J Environ Manag 90:S124–S131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.11.022

Vanloqueren G, Baret PV (2009) How agricultural research systems shape a technological regime that develops genetic engineering but locks out agroecological innovations. Res Policy 38:971–983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2009.02.008

Wezel A, Bellon S, Doré T et al (2009) Agroecology as a science, a movement and a practice. a review. Agron Sustain Dev 29:503–515. https://doi.org/10.1051/agro/2009004

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Annex 1 Description of the Farmers Interviewed in the Study

Annex 1 Description of the Farmers Interviewed in the Study

Farmer considered | Agricultural practices | Commercialisation practices |

|---|---|---|

Farmer 1 | Specialised dairy cattle farmer, Holstein herd with high production goals, not engaged in agroecology | Long chain |

Farmer 2 | Livestock farmer with meat and dairy cattle, but with little integration between crops and livestock farming (purchase of feed, large quantities of mineral inputs) | Long chain |

Farmer 3 | Dairy goat farmer with little autonomy in terms of inputs, but who is trying to graze animals despite dependency on concentrates | Long chain |

Farmer 4 | Dairy cattle farmer with protein autonomy and organic farming | Long chain |

Farmer 5 | Dairy cattle farmer, with a beef and pork workshop, highly engaged in agroecology (agro-forestry, conservation agriculture, feed self-sufficiency, organic, member of local farmer networks) | Long chain for milk |

Farmer 6 | Conventional dairy cattle farmer (no agroecological practices ) | Long chain |

Farmer 7 | Dairy cattle farmer in the process of converting his farm to input-based organic agriculture | Long chain – Potential market for exporting organic powdered milk to China, opened up by the Sodiaal cooperative. |

Farmer 8 | Conventional dairy cattle farmer, with few or no agroecological practices | Commercialises his production via a cooperative grouping together 30 producers across a territory covering three departments. |

Farmer 9 | Dairy cattle farmer with agroecological practices (grazing, food autonomy …) | Coexistence of two types of product outlets (long and short supply chains). |

Farmer 10 | Conventional dairy cattle farmer, but with agroecological practices | Commercialises entirely on short supply chains (sale at the farm, market, produce stores), carrying out transformation himself. |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ryschawy, J., Sarthou, JP., Chabert, A., Therond, O. (2019). The Key Role of Actors in the Agroecological Transition of Farmers: A Case-Study in the Tarn-Aveyron Basin. In: Bergez, JE., Audouin, E., Therond, O. (eds) Agroecological Transitions: From Theory to Practice in Local Participatory Design. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01953-2_8

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01953-2_8

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-01952-5

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-01953-2

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)