Abstract

The focus of the growing discipline of behavioral epidemiology (BE) of infectious diseases is on individual behavior as a key determinant of infection trajectories. This overview departs from the central, but static, role of human behavior in traditional mathematical models of infection to motivate the importance of including behavior into epidemiological models. Our aim is threefold. First, we attempt to motivate the historical and cultural background underpinning the BE revolution, focusing on the issue of rational opposition to vaccines as a natural endpoint of the changed relation between man and disease in modern industrialized countries. Second, we review those contributions, from both mathematical epidemiology and economics, that forerun the current “epidemic” of studies on BE. Last, we offer a more detailed overview of the current epidemic phase of BE studies and, still motivated by the issue of immunization choices, introduce some baseline ideas and models.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) outbreaks of the early 2003 yielded worldwide panic. The characteristics of the SARS virus, mainly transmitted through close contact from person to person [20], brought to everyone’s mind, more than HIV/AIDS, the spectrum of a “modern plague,” at risk of being triggered by historically unprecedented population mobility. The SARS chapter closed leaving only 8,500 cases worldwide (though 800 deaths), but having given a sharp demonstration of how effective might be the diffusion of fear in the globalized world, with the dramatic decline in traveling, tourism, and investments to the Far East [65].

The SARS outbreaks are only one dramatic example of an endless list. In October 2009, in the middle of the H1N1 crisis, the Italian Public Health System started advertising a national immunization campaign against the pandemic flu, targeting 21 million individuals with two doses. A few months later, when the Italian epidemic ended, vaccine coverage was a mere 4. 2 % [87], the worse result in H1N1 immunization in Europe.

In 1998 the prestigious medical journal The Lancet reported an apparently highly circumstantial evidence by Wakefield and coworkers on the striking hypothesis that measles–mumps–rubella (MMR) vaccination might be causally linked with autism. Although the Wakefield’s paper was strongly criticized by other scientists and retracted in 2010 by The Lancet [102], and although its data could not be replicated by other research groups, in subsequent years UK measles immunization fell from 92 % to less than 80 % in 2003, yielding a protracted marked decline in herd immunity, ultimately responsible for measles resurgence [60, 78].

What possibly happened with H1N1 immunization in Italy was that individuals perceived that H1N1 was a mild disease and therefore were not motivated to accept the risk of vaccine adverse events (VAE) from a vaccine which they also perceived as being of insufficiently proven safety. We note that it was not important that the perception was not informed from the best science: what mattered was that this misperception spread faster than other, more correct perceptions, and it was ostensibly confirmed by the subsequent course of the epidemic, which was mild only in comparison to what had been feared based on the early, confused events in Mexico. So eventually only a small proportion were immunized. What happened with MMR uptake in the UK was that news reports of the Wakefield study suddenly raised the perceived risk of VAE, thereby making the perceived utility of vaccination strongly negative. Especially in the context of very low measles circulation at the time, many parents therefore decided not to immunize their children. We note that the perception of measles rarity was “myopic”—rarity was the consequence of herd immunity generated by 20 years of successful immunization—but this is not relevant. What matters is that the rumor spread fast, possibly aggravated by apparently coming from the “best science.”

There are also examples where human behavioral responses played a critical role in controlling infections. There is little doubt that in the HIV/AIDS catastrophe in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), sexual behavior change has been the key in the Ugandan success story [1, 77], which is currently the major instance of success in the control of HIV in SSA, and is becoming an effective strategy as well in other SSA settings such as Zimbabwe where a major HIV epidemic is still ongoing [51, 52].

All these examples document how important human behavior might be for infection spread and for determining the success of public health interventions.

2 Human Behavior and Epidemiological Modeling

The current mathematical theory of infectious disease transmission was built on a few cornerstone ideas and models developed during the so-called Golden Age of theoretical ecology [61, 88, 92]. The most important among such milestones is the homogeneous mixing SIR (susceptible-infective-recovered) model in its two variations, for epidemic outbreaks as seasonal influenza and for endemic infections as measles in large communities in absence of any immunization [3]. In this class of models, behavior is absent: individuals contact (and infect) each other at random, as particles of a perfect gas (the so-called law of mass action [28]) and therefore behavioral influences are ruled out by definition.

In the last 25 years however, thanks to pioneering works aiming to better integrate models with data [3, 53, 54], mathematical models of infectious diseases have crossed their traditional biomathematical boundaries to become central supporting tools for public health decisions, such as determining the duration of travel restrictions or of school closure during a pandemic event, or the fraction of newborn to be immunized for a vaccine-preventable infection, as measles. Some of these models are highly sophisticated both from the computational and data requirements’ viewpoints [5, 39, 73]. In these models, the importance of human behavior is implicit in the acknowledged role of social or sexual contact patterns as the key determinant of the transmission of both close-contact infections, as influenza or measles, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as HIV/AIDS. In recent years there have been great advances in the understanding of contact patterns [59, 75, 108], which made available rich information about, for example, the average number of persons of different ages an individual encounters in a typical day. This information is allowing great improvements in model parameterization and validation. However, the point of behavioral epidemiology lies exactly here: though sophisticated, current models treat these contact patterns statically, as a universal constant, exactly as in the simple SIR model. This means that behavior is totally unaffected by the state of the disease, for example, individuals continue to contact each other however low or high might be the perceived risk of contracting the infection. As these static contact patterns refer to normal situations, the ensuing models are unlikely to apply under stressed conditions as those observed during a dangerous epidemic or a period of panic raised by a pandemic threat [38]. Similarly, models used to evaluate the impact of immunization programs treat vaccine uptake as a constant [3], totally unaffected by individuals’ risk perceptions about the disease and the vaccine, and despite the fact that it is the degree of acceptance of the public that will ultimately determine the success of the program unless mandatory policies can be strictly enforced. Clearly, phenomena such as vaccine scares cannot be captured by treating vaccine coverage as a fixed, exogenously determined input parameter.

As suggested by the above examples, this postulated static human behavior is therefore an unrealistic abstraction. Individuals are neither static nor passive: they can change their social behavior spontaneously in response to a pandemic threat, can adaptively vaccinate in response to a sequence of seasonal influenza epidemics, or can decide not to vaccinate their children after a comparison between the perceived costs and benefits of a vaccination program, thereby threatening its success. In modern times, these decision dynamics are facilitated by the power of modern communication technologies, which allow real-time, selective access to broadly available information to the extent that certain reliable influenza data can now be mined from individuals’ search activities on the web during influenza seasons [49].

The challenging task of modeling, explaining and possibly predicting these phenomena is the ultimate purpose of the emerging field of behavioral epidemiology of infectious diseases. As the above examples clearly show, the major novelty that distinguishes BE from, for instance, traditional biomathematical approaches or economic approaches in epidemiology (e.g., cost–benefit analyses of public programs) is the focus on modeling behavioral changes in response to infection dynamics [44] as a key determinant of infection trajectories, and therefore on the complex interplay between agents’ decisions, on one hand, and the transmission and control of infections, on the other hand [38, 44].

3 Behavioral Epidemiology: Why Now?

Later on in this overview, BE is described as currently being in its “epidemic” phase. A question is then, why right now? We argue that a rich “humus” was supplied by the current scientific, cultural, and socio-demographical context of industrialized countries which has dramatically changed the relationship between humans and disease. In this context, individuals frantically demand “predictability” during a pandemic event [38] or “rationally” refuse a vaccine—the invention that has protected so much human life in the last hundred years. In short, technology has turned us from victims of nature per se to victims of our own actions locked in a feedback loop with natural forces. This is why it is now that studying BE is important, and we expand on this in the following paragraphs. Until 1750 the millenary fight between man and disease—the third horseman of the Apocalypse—is the story of a long-lasting unperturbed ecological equilibrium. During this fight human behavioral responses to infectious disease threats always took place, as is documented by the great writers, from the Athens’ “plague” described by Thucydides, to the Black Death whose visit to Florence was immortalized by Giovanni Boccaccio in the “Decameron,” to the seventeenth-century plague described by Daniel Defoe and Samuel Pepys, and two centuries later on by Alessandro Manzoni (Fig. 1). However, most these responses are reported by historians as taking place at the community level (e.g., enforcing quarantine of sick individuals and also of goods [97], or closing the city gates,Footnote 1 and mass migrations—especially by rich people—toward the countryFootnote 2), so that individual actions, though reported, were usually perceived as minor and passive. Most of all these actions, collective or individual, were lacking any scientific basis.Footnote 3 Most importantly, these actions were unable to mitigate plague epidemics or to perturb the ecological equilibrium between man and disease: infectious diseases continued to impose a major and intractable health burden on populations worldwide for several millenniums.

(upper left panel) Thucydides, who described with many details the plague outbreak that frightened Athens during 430–429 BC and resulted in significant socioeconomic reactions. The etiological agent is still unknown; (upper right) Giovanni Boccaccio, whose Decameron (written between 1351 and 1353) supplied a dramatic description of the devastating impact of the Black Death passed through Florence in 1350. The book is the story of ten young people (seven women and three men) who flee from the devastated Florence and self-quarantine (an early example of social distancing) into a villa in the countryside, where they pass time telling stories. (bottom left) Daniel Defoe, who was five years old when the bubonic plague struck London in 1665, which he subsequently described in his Journal of the Plague Year. (bottom right) collection of dead bodies during the outbreak of bubonic plague in Milan, described in Manzoni’s “The Betrothed.” In Chap. 22 he underlies the possibly devastating role played the great procession authorized by the Cardinal of Milan, Federico Borromeo, ironically undertaken to invoke God’s favor

During the last two centuries, however, thanks to the sanitation revolution (such as potable water) and to medical discoveries (such as vaccines), humanity has attained amazing achievements in the control of infectious diseases and reduction in associated mortality. These achievements have perturbed the equilibrium between humans and disease, yielding that epochal change in the casual composition of mortality from infectious (and nutritional) diseases to chronic degenerative ones known as the “epidemiological transition” [76, 96, 103]. The epidemiological transition has been a major determinant of the huge progress in survival and health in industrialized countries, where life expectancy increased from 25 to 30 years in preindustrial societies to more than 80 years in the current period [69, 103], which in turn triggered fertility decline, the escape from Malthusian traps, and eventually, in a virtuous circle, sustained economic development [14, 45]. Further advances with vaccines, such as vaccines that protect against oncogenic viruses such as HBV and HPV, are making a reality out of previously utopian conceptions of life in a future world free from infectious diseases [22].

This amazing success against infectious diseases and their associated mortality in the industrialized world, and the ensuing huge increase in the value of human life in current low-mortality/low-fertility societies, is however changing the relation between man and infection. What was the rule in the ancient demographic regime—losing 50 % of children before age 15 as a consequence of infections and malnutrition [69]—has been completely reversed in today’s small, highly educated postindustrial families.

There are several evidences of this changed attitude, and surely the main one is represented by the increasing frequency of episodes of oppositions to vaccines [47, 70, 78], the single invention that possibly more than other has contributed to the changed relation between man and infection.

The history of immunization in the western world has always been characterized, already since the introduction of smallpox vaccine, by phases of declining uptake. However, most of this historical opposition to vaccination is thought to be due to conscientious, religious, or philosophical reasons [90]Footnote 4 In contrast, current societies are gradually facing the more complex challenge of rational opposition to vaccines [8, 9, 31, 33].Footnote 5 Consider the example of an infection that is preventable by childhood immunization, as measles, for which we assume there are only two options, i.e., vaccinating or not vaccinating at birth. By rational opposition we mean, under voluntary vaccination, the parents’ choice not to vaccinate children after a comparison between the perceived benefit and cost of vaccination.

The cost of vaccination can be conceived of as the perceived risk of suffering some vaccine-associated adverse event (VAE). In the simplest case this can be taken as a constant (e.g., as in [8]), though individuals’ perceptions about a given vaccine are possibly affected by perceptions about other vaccines as well. On the other hand the perceived benefit of vaccination can be estimated by the perceived risk of suffering death (or serious morbidity) from the disease, which can in turn be estimated as the product of some measure of the current perceived risk of acquiring infection, i.e., the force of infection, and the conditional probability of death, as a consequence of infection. European data suggest that, due to improved nutrition and sanitation, the probability of death following infection from measles and other childhood infections fell off at least two orders of magnitude from 1860 to 1950 [34, 35], i.e., prior to when most immunization began. As for the risk of infection, the simple endemic SIR model with immunization at birth [3] suggests that for highly transmissible infection as measles, with a basic reproduction number about 15, a vaccine uptake of approximately 90 %, as was typical in many European countries during the last two decades, would create strong herd immunity by decreasing both the endemic prevalence and the risk of infection by about 30 times compared to the case of no vaccination. This straightforwardly yields the perception that the infection is no longer circulating. These numbers suggest that sanitation progress and mass immunization, two major factors underlying the changed relation between humans and their diseases, are now acting as “killers” of the perceived rewards of immunization [33]. In simple words it is the vaccine’s success in controlling infections that promotes “rational” opposition, leading to declining vaccine coverage and potentially to infection reemergence.

The modeling of vaccination choices and rational opposition is currently a major topic of investigation in BE [8–10, 13, 29–33, 72, 85, 86]. Details about how vaccination choices can be incorporated into transmission models to capture the emergent population-level implications of vaccinating behavior will be presented in Sect. 5 of this overview.

4 Incubation of BE: Mathematical Forerunners, HIV/AIDS, and the Free-Rider Problem

The first mathematical epidemiology papers incorporating behavioral concepts date back to the end of the 1970s and were mainly motivated by mathematical questions, i.e., investigating extensions of the basic SIR model including nonlinear forces of infection. The first among such efforts [19] investigated the effects of a prevalence-dependent [44] contact rate, i.e., a contact rate reacting to the (perceived) prevalence of infective individuals, on the epidemic SIR model. To our knowledge, this is the first study including the concept of social distancing in epidemic modeling. Extensions of these ideas to endemic infections were developed shortly thereafter [67, 68].

However, the first great impulse to the development of behavioral epidemiology as a discipline was provided by the HIV/AIDS threat, beginning in the 1980s. The combination of a long incubation period, with difficult and costly treatment, and the lack of a vaccine have made instilling preventive behavior through the dissemination of information on risky behavior with respect to sexual or intravenous drug use the main control strategy, especially in poor resource settings.

In a situation almost completely lacking reliable data on individuals’ responses to the spread of epidemics, mathematical modeling has rapidly become the main tool for understanding the effects of behavior change on HIV trajectories. The first contribution is [91], where the effects of switching from high to low risk behavior on the epidemic threshold parameter were investigated by a two-group model with preferred mixing, subsequently extended in [66], and estimated in [99]. In [15] data on HIV/AIDS in San Francisco are used to provide a model-based estimate of the decline in at-risk behavior required to eliminate, even in presence of a vaccine, the infection. The first warning on the possibility that a protective vaccine increases epidemic severity by raising at-risk behavior is also put forth. Several papers have used simple models to investigate the static and dynamic effects of various forms of behavioral responses including prevalence-dependent recruitment into the at-risk population and reducing contact rates after screening or treatment [50, 56, 105, 106]. The effects of prevalence-dependent sexual mixing patterns were investigated in [58]. A first attempt to integrate optimal choices of sexual partners into HIV transmission models is [64]. These are pioneering works of an endless list.

In parallel to the explosion of studies on behavior change in relation to HIV/AIDS, the first studies on vaccinating behavior appeared. In a seminal epidemiological paper, Fine and Clarkson [40] compare the different perspectives of the individual and the public good toward immunization and supply the first formulation of the result that under voluntary vaccination, rational individuals’ decisions would most often yield a lower vaccine uptake than is optimal for the community as a whole. This result remained essentially unnoticed to epidemiological modelers until recent times and was independently rediscovered later by economists as well, but in relation to the debate between free market and compulsory immunization formulated as a free-rider problem. Immunization against a communicable infection by a vaccine that protects against infection has a twofold protective effect: a direct one for those who are immunized and an indirect one for those who are not, due to the reduced circulation of the virus in the community which reduces the risk of acquiring infection for those non-immunized. Free-riding arises when some individuals take advantage of this indirect protection (herd immunity) created by those who choose to be vaccinated, to avoid immunization and its related costs. In [18] the conditions under which free-riding can be overcome without compulsory vaccination, through taxes or subsidies, are investigated, while [41] departs from the problem investigated in [18] and shows that in a special case of SI infections the market and the government optimal solutions may be identical. Geoffard and Philipson [48] use an SIR model for a childhood infection with vaccine uptake dependent upon infection prevalence as a measure of perceived risk of infection, as empirically supported by analyses in [80], to offer the first proof of the supposed impossibility of eliminating infection under voluntary vaccination. The simple argument is that a successful immunization program will strongly reduce infection prevalence and therefore also reduce the perceived risk of disease, thereby killing the vaccine demand. These works formed the “humus” for the current outbreak of BE studies, discussed in the next section.

5 The “Epidemic Phase” of Behavioral Epidemiology

Behavioral epidemiology is arguably in an “epidemic phase,” with many dozens of publications in the area in the past decade [2, 4, 6–11, 13, 16, 17, 21, 23–27, 29–33, 36, 37, 42–44, 46, 62, 63, 72, 79, 81–86, 89, 93–95, 101, 104, 109]. This attention has come primarily from biomathematicians and theoretical biologists, for whom an interest in behavioral epidemiology comes naturally due to their long-standing involvement in both mathematical epidemiology [53] and evolutionary game theory [71]. It is also possible that the MMR vaccine scare of the late 1990s and the oral polio vaccine (OPV) scare early in the twenty-first century contributed to this surge of interest [57].

Some of this development has been described in recent review papers [13, 44, 63]. Here, we provide a broad overview of the behavioral epidemiology literature in the past ten years, starting with a discussion of the broad range of approaches that have been adopted.

5.1 Model Taxonomy

Funk et al. suggest that the literature can be classified in terms of (1) source of information used by decision-makers, (2) type of information used by decision-makers, and (3) effect of behavioral change [44]. For example, decision-makers may either base their decisions on global sources of information available to everyone (television, World Wide Web) [7, 8, 11, 21, 24, 27, 31, 32, 37, 46, 62, 86, 101, 104], or they may base their decisions on local sources available only to a subset of the population (such as information passed through word of mouth between acquaintances) [4, 36, 37, 43, 79, 89, 93, 109]. Likewise, decision-makers may base their decisions on perfect knowledge of disease prevalence [4, 7, 9, 11, 21, 27, 31, 32, 46, 79, 86, 93, 104, 109], and/or they may base their decisions on sources completely independent from prevalence or base only loosely on prevalence, such as peer opinions or faulty media representations [8, 24, 36, 37, 43, 62, 89, 101]. Finally, the effect of behavioral change may be to change individual disease states [7–9, 11, 21, 24, 31, 32, 36, 46, 79, 86, 89, 104], model parameters [4, 27, 37, 43, 62, 101] or contact structure [37, 84, 93, 109].

One could also distinguish the literature by the intervention concerned. For instance, the majority of papers are specifically concerned with vaccinating behavior, although some papers are concerned with social distancing [43, 84, 93, 109] or antiviral drugs [100]. Some models are intended for specific diseases, such as influenza [17, 46, 94, 104], smallpox [6, 11, 27], or human papillomavirus [7], while many models are intended to be more general [8, 9, 16, 21, 36, 43, 72, 86, 93].

Earlier models in behavioral epidemiology tended to be either mechanistic with respect to transmission and phenomenological with respect to behavior [19] or mechanistic with respect to behavior and phenomenological with respect to transmission [40], whereas more recent models represent both behavior and transmission mechanistically. If mechanistic with respect to both, they have sometimes been termed “behavior-prevalence” or “behavior-incidence” models, because the full mechanistic model is formed by coupling two independent mechanistic submodels, one for behavior and one for transmission [13, 63].

Mechanistic transmission models are often deterministic compartmental models, although there is also a distinct subset of the literature concerned with contact networks [26, 42, 43, 79, 93, 109]. Likewise, mechanistic behavioral models may be based on theory about behavior or perception stemming from psychology [4, 8, 16, 24, 26, 27, 29, 42, 43, 79, 93], and/or some of these approaches may be specifically game theoretical, assuming that individuals act to rationally optimize their own payoffs [9, 11, 72, 83, 84, 86, 94]. In the next two sections, we describe two examples of behavior-incidence models, the first of which represents a game theoretical approach to behavioral epidemiology.

5.2 A Game Theoretical Example

Game theoretical approaches specify a game that entails strategic interactions between individuals, and identify the Nash equilibrium of the game. When each player is playing their Nash equilibrium strategy, no player can obtain a higher payoff by switching to another strategy. Therefore, a population at the Nash equilibrium is expected to remain there. We note that one can furthermore define a convergently stable Nash equilibrium, meaning that a population whose initial conditions place it away from the Nash equilibrium will eventually converge to the Nash equilibrium and stay there [9]. Many behavioral epidemiological approaches are akin to game theory, in that they describe scenarios where strategic interactions exist and they specify payoffs [40, 43, 79, 93], but strictly speaking they are not game theoretical unless they specify a game and identify its Nash equilibria (or its evolutionarily stable states [71] or similar such solutions).

5.2.1 Model Description

An example of an approach to behavioral epidemiology that combines a game theoretical model of human behavior with a mechanistic disease transmission model is the simple vaccination game for pediatric infectious diseases, appearing in [9]. This game captures many of the basic features of mechanistic approaches to behavioral epidemiology modeling. We explain the game and its Nash equilibrium intuitively as follows. The game is a population game where individuals play against the outcome of the average behavior of the population. Individuals can either vaccinate or not vaccinate. The payoff to vaccinate is − r v , where r v is the vaccine cost, i.e., the perceived probability of complications due to vaccine (the payoff is negative because maximizing payoff is the same as minimizing adverse health impacts). The parameter r v could equally well be interpreted as being the financial costs plus monetized health costs due to complications. This payoff function implies that the vaccine is perfectly efficacious, because the individual only pays the one-time cost r v upon vaccinating and never any infection cost. The payoff not to vaccinate is \(-r_{i}\pi (p)\), where π(p) is the perceived lifetime probability that a nonvaccinator becomes infected if the vaccine coverage in the population is p and r i is the perceived probability of significant morbidity if a nonvaccinator ends up getting infected. We suppose that \(\pi (p)\) is strictly decreasing in p and that \(\pi (p_{crit}) = 0\) for some \(p_{crit} < 1\), due to herd immunity. We allow individuals to adopt a mixed strategy to vaccinate with probability P, where \(0 \leq P \leq1\). At a steady-state equilibrium in a population where everyone is playing P, we note that p = P.

5.2.2 Finding the Nash Equilibrium

Suppose first that \(r_{v} \geq r_{i}\pi (0)\), such that the cost to vaccinate exceeds the cost not to vaccinate, even if no one else is vaccinating and hence the infectious disease is rampant. Then \({P}^{{_\ast}} = 0\) is the Nash equilibrium: suppose that everyone is playing \({P}^{{_\ast}} = 0\); then, a small group considering switching to a strategy \(Q > {P}^{{_\ast}}\) would, as a result of their actions, increase the vaccine coverage slightly; this would decrease the probability that nonvaccinators are infected since \(\pi (p) < \pi (0)\) for all p > 0, and meanwhile, the payoff to vaccinate would remain unchanged; thus, by starting to vaccinate with a higher probability, the small group would only worsen their payoff by changing strategies; as a result, there is no incentive for anyone to start vaccinating and so \({P}^{{_\ast}} = 0\) is the Nash equilibrium when \(r_{v} \geq r_{i}\pi (0)\).

Now suppose that \(r_{v} < r_{i}\pi (0)\). In this case, the Nash equilibrium occurs at \({P}^{{_\ast}}\) such that the payoff to vaccinate equals the payoff not to vaccinate, i.e., \(-r_{v} = -r_{i}\pi ({p}^{{_\ast}})\) (where \({P}^{{_\ast}} = {p}^{{_\ast}}\)). The reason for this lies in the fact that \(\pi (p)\) must be strictly decreasing in p. Suppose in a population where everyone is playing P ∗ a small group of individuals considers playing \(Q > {P}^{{_\ast}}\). This would increase the overall vaccine coverage in the population slightly, meaning that the probability that a nonvaccinator is infected would be lower, meaning that the payoff not to vaccinate now exceeds the payoff to vaccinate. As a result, the small group would only receive a lower payoff if they switched to \(Q > {P}^{{_\ast}}\) and, if they are rational, would probably decide against that option. Similarly, at P ∗ , there is no incentive for anyone to start vaccinating with probability \(Q < {P}^{{_\ast}}\). Hence, we expect that a population existing at \({P}^{{_\ast}}\) would stay at P ∗ , where P ∗ satisfies \(-r_{v} = -r_{i}\pi ({P}^{{_\ast}})\).

It is also possible to show that \({P}^{{_\ast}}\) is unique and locally convergently stable and that \({p}^{{_\ast}} < p_{crit}\), such that the Nash equilibrium coverage is always below the threshold coverage at which the infection would be completely eliminated from the population. Because self-interested behavior thereby precludes eradication of a vaccine-preventable infection, this can be interpreted as a form of “free-riding,” or equivalently, policy resistance [98]. Free-riding is a common prediction of behavioral epidemiological models, although exceptions occur (e.g., see [79, 94]). Much work in behavioral epidemiology is concerned with the extent of free-riding behavior and conditions for its emergence.

5.2.3 Introducing a Mechanistic Disease Transmission Model

By introducing a compartmental model such as the susceptible-infectious-recovered (SIR) model with births and deaths, it becomes possible to specify a function form for \(\pi (p)\) and thus make quantitative predictions of the Nash equilibrium coverage. The SIR model equations are

where S is the proportion of the population that is susceptible, I is the proportion infectious, R is the proportion recovered, μ is the mean birth and death rate, \(\beta \) is the mean transmission rate, \(1/\gamma \) is the mean infectious period, and p is the vaccine coverage (assuming, for simplicity, that individuals are never infected before being vaccinated) [53]. From the equilibrium solutions of these equations we can determine π(p) and thus p ∗ from \(-r_{v} = -r_{i}\pi ({p}^{{_\ast}})\). For the pediatric infectious disease vaccination game using (1)–(3), the Nash equilibrium coverage \({p}^{{_\ast}}\) when \(r_{v} < r_{i}\pi (0)\) is:

suggesting that Nash equilibrium vaccine coverage in a population attempting to optimize their own health-related payoff is higher when the basic reproduction number R 0 is higher, when \(r_{v}\) is lower or when r i is higher.

5.3 An Example Based on Imitation Processes

A contrasting, non-game theoretical approach appears in [8, 10]. In order to achieve the dynamic description required to capture temporally extended phenomena such as vaccine scares, the SIR equations with birth and death are modified by replacing a constant vaccine coverage p by a potentially time-varying vaccine coverage x, where x is determined by a differential equation capturing how individuals learn their strategic behaviors from others:

In these equations, all parameters and variables are as in Sect. 5.3, except x is the proportion of the population favoring vaccination at time t, m is the sensitivity of individuals to prevalence I (where higher values of m mean that individuals perceive the disease as more harmful), and k quantities are the combined rate at which individuals sample others and probability of switching strategies if they find that others are receiving a higher payoff for playing the other strategy. The probability of switching strategies is proportional to the difference in the vaccinator payoff, − r v , and the nonvaccinator payoff, \(-r_{i}mI\). Individuals do not know their lifetime probability of being infected, but rather adopt a “rule of thumb” that the cost of not vaccinating is proportional to the current disease incidence I, hence the nonvaccinator payoff − r i mI. Since \(R = 1 - S - I\), we note that equation (7) can be dropped.

The analysis of [8] is not really game theoretical because the Nash equilibria were not identified and the focus was on dynamics away from equilibrium. This type of approach has been described as a game dynamic approach, since it describes how populations may evolve over time toward, or away from, Nash equilibria [55]. However, the model equations (5)–(8) nonetheless describe a situation where strategic interactions exist due to the feedbacks between vaccinating behavior and disease prevalence. And, in principle, connections exist and can be made between the equilibria of the model equations and Nash equilibria of the underlying game. For example, Lyapunov stable or asymptotically stable equilibria of the model equations can also be Nash equilibria under certain conditions [55].

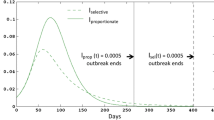

Equations (5)–(8) exhibit a broad range of behavior, including a disease-free equilibrium where no one vaccinates (\(I = x = 0\)), a disease-free equilibrium where everyone vaccinates (I = 0, x = 1), an endemic equilibrium where a fixed proportion of the population vaccinates (I > 0, x > 0), an endemic equilibrium where no one vaccinates (I > 0, x = 0), and a stable limit cycle where x and I oscillate indefinitely (see Fig. 2) [74]. However, as before, because of free-riding behavior, vaccine coverage x never reaches the level p crit that enables elimination of the infection. Variants of this model have been shown to provide parsimonious explanations of vaccine coverage and case notification data from vaccine scares in England and Wales, and in the deterministic regime the model also appears to have predictive power [10].

The κ-ω parameter plane illustrating dynamics of model described by (5)–(8). \(\kappa\equiv kr_{v}\) and \(\omega\equiv mr_{i}/r_{v}\). I: stable endemic, pure nonvaccinator equilibrium. II: stable endemic, partially vaccinating equilibrium. III: stable limit cycle. Other parameters are \(\mathcal{R}_{0} = 10\), \(1/\gamma= 10\mbox{ days}\), \(1/\mu= 50\;\mbox{ years}\). Figure reproduced from [8]

5.4 A Prevalence-Based Modeling Example

A contrasting approach appears in [31]. In order to achieve the dynamic description required to capture temporally extended phenomena such as changing levels of vaccine coverage over time, many approaches augment a compartmental model by replacing a constant vaccine coverage by an information dependent, potentially time-varying vaccine coverage that captures how individuals make vaccinating decisions according to information about incidence or prevalence of infection:

Here, S, I, R, p, \(\beta (t)\) and μ are as in Sect. 5.3 except β is potentially time-varying. U is the proportion of vaccinated individuals and M is an information variable governing the signal available to individuals as a function of prevalence or incidence of infection. Since \(R = 1 - S - I - U\), we note that equation (7) can be dropped.

Rather than taking p from game theoretical considerations, in this approach, p = p(M) where M depends directly on current or past states of the disease in the population. When depending on current states, the authors explore three possibilities for M:

-

\(M = \alpha \beta SI\): information governing vaccinating behavior depends on the current incidence, where \(\alpha \) is a reporting rate.

-

M = kI: information governing vaccinating behavior depends on the current prevalence, where k is a parameter subsuming aspects such as pathogenicity [8].

-

\(M = \alpha \beta I/(\mu+ \alpha \beta I)\): information governing vaccinating behavior is a saturating function of current incidence [86].

In comparison, M can also depend on past states, such as according to

-

\(M(t) = \int\limits_{-\infty }^{t}g(S(\tau ),I(\tau ))K(t - \tau )d\tau \),

where K governs memory decay. The parameter p can in turn depend upon M according to a constant term p 0 plus a saturating Michaelis–Menten function \(p_{1}(M)\), for example:

Strictly speaking, the analysis of [31] is not game theoretical because Nash equilibria are not identified. However, this type of approach might potentially be described as a game dynamic approach, since it may describe how populations may evolve over time toward, or away from, Nash equilibria [55]. The model equations (5)–(8) nonetheless describe a situation where strategic interactions exist due to the feedbacks between vaccinating behavior and disease prevalence. And, in principle, connections exist and can be made between the equilibria of the model equations and Nash equilibria of the underlying game. For example, Lyapunov stable or asymptotically stable equilibria of the model equations can also be Nash equilibria under certain conditions [55].

Equations (5)–(8) exhibit a broad range of behavior, including fixed points and stable limit cycles where vaccine uptake and disease prevalence oscillate over time in a “boom-bust” cycle, even when memory decays exponentially. Hence, as a result of information-dependent vaccination, the globally asymptotically stable endemic equilibrium of the basic SIR equations is often destabilized. Moreover, as in Sect. 5.3, for p 0 sufficiently small, vaccine coverage p can never be sustained at the level \(p_{crit}\) that enables elimination of the infection because of “free-riding behavior” or equivalently “rational exemption.” Under some assumptions, it is also possible to derive an expression for the classic interepidemic interval in the presence of information-dependent vaccination [31].

6 Concluding Comments

The growth in the behavioral epidemiology literature has been significant, but what will be required for this “epidemic” to become an “endemic?” In order that this approach becomes an established part of applied mathematics and theoretical biology, we suggest that one potential future course for these models involves greater realism in how behavior is captured in the models, greater realism in transmission processes, and closer integration of models and data [7, 10, 38, 46, 82, 94]. Other answers to this question will appear in the following pages, and these directions by no means exhaust how the field can be further developed. Incorporating greater realism in transmission processes should come easily to the mathematical epidemiologists; however, incorporating greater realism into models of vaccinating behavior will require closer collaboration with psychologists, sociologists, epidemiologists, and economists.

Notes

- 1.

In Rome, during the seventeenth-century plague special additional walls were built around the city [97].

- 2.

As S. Pepys wrote during the London Plague: “I find all the town almost going out of town, the coaches and wagons being all full of people going into the country,” as reported by [97]. The same paper also reports that the parish of Covent Garden, London, wrote “all the gentry and better sort of tradesmen being gone.”

- 3.

For example, based on historical documents, Manzoni describes in his masterpiece novel The Betrothed the behavioral changes of the citizens of Milan, during the plague in 1629, mainly due to their fear of the “poisoners”: imaginary villains that were thought to voluntarily spread the disease through mysterious ointments causing the disease. In particular, Manzoni describes as the epidemic peak following a procession against the plague is not attributed to the crowding during the procession nor to “the infinite multiplication of random contacts” (note the surprising accuracy of Manzoni’s language in describing the contagion process, despite this phrase has been written in 1827). The most of people attributed, indeed, the peak to the poisoners, who would have had an easier task, in the crowd of the procession, in diffusing their evil ointments in order to accomplish their “impious plan.”

- 4.

We shortly mention that there are also a number of a priori opposers to vaccinations, who irrationally believe that vaccines are a sort of Manzoni’s “ointments.” Quite interestingly, this observation is in line with the fact that some anti-vaccination arguments remained unchanged since the Jenner’s times [107].

- 5.

Although out of the aims of this work, we remark here that the partisans of most extreme anti-vaccination positions are very able in spreading their ideas through the World Wide Web [107], so that WWW 2.0 might represent not only an opportunity but also a challenge for vaccination decisions [12]. This topic, in particular, is worthwhile to be studied in the future.

References

Allen, T., Heald, S.: J. Int. Dev. 16, 1141 (2004)

Althouse, B.M., Bergstrom, T.C., Bergstrom, C.T.: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1696 (2009)

Anderson, R.M., May, R.M.: Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control. Oxford University Press, Oxford (1991)

Bagnoli, F., Lio, P., Sguanci, L.: Phys. Rev. E 76, 061904 (2007)

Bajardi, P., Poletto C., Ramasco, J.J., Tizzoni, M., Colizza, V., Vespignani, A.: PLOS ONE 6, e16591 (2011)

Barrett, S.: Public Choice 130, 179 (2007)

Basu, S., Chapman, G., Galvani, A.: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 19018 (2008)

Bauch, C.T.: Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 272, 1669 (2005)

Bauch, C.T., Earn, D.J.D.: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 13391 (2004)

Bauch, C.T., Bhattacharyya, S.: PLoS Comput. Biol. 8, e1002452 (2012)

Bauch, C.T., Galvani, A.P., Earn, D.J.D.: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10564 (2003)

Betsch, C., Brewer, N.T., Brocard, P., Davies, P., Gaissmaier, W., Haase, N., Leask, J., Renkewitz, F., Renner, B., Reyna, V.F., Rossmann, C., Sachse, K., Schachinger, A., Siegrist, M., Stryk, M.: Vaccine 30, 3727 (2012)

Bhattacharyya, S., Bauch, C.T.: Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 8, 842 (2012)

Bloom, D., Cannings, D.: World Econ. 5, 57 (2004)

Blower, S.M., McLean, A.R.: Science 265, 1451 (1994)

Brauer, F.: BMC Public Health 11(Suppl 1), S3 (2011)

Breban, R., Vardavas, R., Blower, S.: Phys. Rev. Lett. E 76, 031127 (2007)

Brito, D., Sheshinski, E., Intriligator, M.: J. Pub. Econ. 45, 69 (1991)

Capasso, V., Serio, G.: Math. Biosci. 42, 43 (1978)

CDC: SARS. http://www.cdc.gov/sars

Chen, F.: J. Math. Biol. 53, 253 (2006)

Chen, R.T., Orenstein, W.A.: Epidemiol. Rev. 18, 99 (1996)

Chen, F., Cottrell, A.: J. Biol. Dyn. 3, 357 (2009)

Coelho, F.C., Codeco, C.T.: PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000425 (2009)

Cojocaru, M.G., Bauch, C.T., Johnston, M.D.: Bull. Math. Biol. 69, 1453 (2007)

Cornforth, D.M., Reluga, T.C., Shim, E., Bauch, C.T., Galvani, A.P., Meyers, L.A. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1001062 (2010)

Del Valle, S., Hethcote, H., Hyman, J.M., Castillo-Chavez, C.: Math. Biosci. 195, 228 (2005)

Diekmann, O., Heesterbeek, J.A.P.: Mathematical Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases. Springer, Berlin (2000)

d’Onofrio, A., Manfredi, P.: J. Theor. Biol. 256, 473 (2009)

d’Onofrio, A., Manfredi, P.: J. Theor. Biol. 264, 237 (2010)

d’Onofrio, A., Manfredi, P., Salinelli, E.: Theor. Pop. Biol. 71, 301 (2007)

d’Onofrio, A., Manfredi, P., Salinelli, E.: Math. Med. Biol. 25, 337 (2008)

d’Onofrio, A., Manfredi, P., Poletti, P.: J. Theor. Biol. 273, 63 (2011)

Duncan, C.J., Duncan, S.R., Scott, S.: Theor. Pop. Biol. 52, 155 (1996)

Duncan, C.J., Duncan, S.R., Scott, S.: Epidemiol. Infect. 117, 493 (1996)

Eames, K.T.D.: J. R. Soc. Interface 6, 811 (2009)

Epstein, J.M., Parker, J., Cummings, D., Hammond, R.A.: PLoS ONE 3, e3955 (2008)

Ferguson, N.: Nature 446, 733 (2007)

Ferguson, N.M., Cummings, D.A.T., Cauchemez, S., Fraser, C., Riley, S., et al.: Nature 437, 209 (2005)

Fine, P., Clarkson, J.: Am. J. Epidemiol. 124, 1012 (1986)

Francis, P.J.: J. Public Econ. 63, 383 (1997)

Fu, F., Rosenbloom, D.I., Wang, L., Nowak, M.A.: Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 278, 42 (2011)

Funk, S., Gilad, C., Watkins, C., Jansen, V.A.A.: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 6872 (2009)

Funk, S., Salathe, M., Jansen, V.A.A.: J. R. Soc. Interface 7, 1247 (2010)

Galor, O., Weil, D.N.: Am. Econ. Rev. 89, 150 (1999)

Galvani, A., Reluga, T., Chapman, G.: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 5692 (2007)

Gangarosa, E.J., Galazka, A.M., Wolfe, C.R., Phillips, L.M., Gangarosa, R.E., et al.: Lancet 351, 356 (1998)

Geoffard, P.-Y., Philipson, T.: Am. Econ. Rev. 87, 222 (1997)

Ginsberg, J., Mohebbi, M.H., Patel, R.S., Brammer, L., Smolinski, M.S., et al.: Nature 457, 1012 (2009)

Hadeler, K.P., Castillo-Chavez, C.: Math. Biosci. 128, 41 (1995)

Hallett, T.B., Gregson, S., Mugurungi, O., Gonese, E., Garnett, G.P.: Epidemics 1, 108 (2009)

Halperin, D.T., Mugurungi, O., Hallett, T.B., Muchini, B., Campbell, B., Magure, T., Benedikt, C., Gregson S.: PLoS Med. 8, 061904 (2012)

Hethcote, H.: SIAM Rev. 42, 599 (2000)

Hethcote, H.W., Yorke, J.A.: Gonorrhea. Transmission Dynamics and Control. Springer, Berlin (1984)

Hofbauer, J., Sigmund, K.: Evolutionary Games and Population Dynamics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1998)

Hsieh, Y.H.: IMA J. Math. Appl. Med. Biol. 13, 151 (1996)

Hughes, V.: Nature Med. 12, 1228 (2006)

Hyman, J.M., Li, J.: SIAM J. Appl. Math. 57, 1082 (1997)

Iozzi, F., Trusiano, F., Chinazzi, M., Billari, F.C., Zagheni, E., et al.: PLoS Comput. Biol. 6, e1001021 (2010)

Jansen, V.A.A., Stollenwerk, N., Jensen H.J., Ramsay, M.E., Edmunds, W.J., Rhodes, C.J.: Science 301, 804 (2003)

Kermack, W.O., McKendrick, A.G.: Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 115, 700 (1927)

Kiss, I.Z., Cassell, J., Recker, M., Simon, P.L.: Math. Biosci. 225, 1–10 (2009)

Klein, E., Laxminarayan, R., Smith, D.L., Gilligan, C.A.: Env. Dev. Econ. 12, 707 (2007)

Kremer, M.: Q. J. Econ. 111, 549 (1996)

Kuo, H.-I., Chen, C.-C., Tseng, W.-C., Ju, L.-F., Huang, B.-W.: Tour. Mgmt. 29, 917 (2008)

Li, J.: Math. Comput. Model. 16, 103 (1992)

Liu, W.M., Levin S.A., Iwasa Y.Y.: J. Math. Biol. 23, 187 (1986)

Liu, W.M., Hethcote, H.W., Levin S.A.: J. Math. Biol. 25, 359 (1987)

LiviBacci, M.: A Concise History of World Population. Blackwell, Oxford (2005)

Luman, E.T., Fiore, A.E., Strine, T.W., Barker, L.E.: J. Am. Med. Assoc. 291, 2351 (2004)

Maynard-Smith, J.: Evolution and the Theory of Games. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1982)

Manfredi, P., Della Posta, P., d’Onofrio, A., Salinelli, E., Centrone, F., Meo, C., Poletti, P.: Vaccine 28, 98 (2009)

Merler, S., Ajelli, M., Pugliese, A., Ferguson, N.M.: PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002205 (2011)

Montopoli, L., Bhattacharyya, S., Bauch, C.T.: Can. Appl. Math. Q. 17, 317 (2009)

Mossong, J., Hens, N., Jit, M., Beutels, P., Auranen, K., et al.: PLoS Med. 5, e74 (2008)

Omran, A.R.: Milbank Mem. Fund. Q. 49, 509 (1971)

Parkhurst, J.O.: Lancet 360, 9326 (2002)

Pearce, A., Law, C., Elliman, D., Cole, T.J., Bedford, H.: Br. Med. J. 336, 754–757 (2008)

Perisic, A., Bauch, C.T.: PLoS Comput. Biol. 5, e1000280 (2009)

Philipson, T.: J. Hum. Res. 31, 611 (1996)

Poletti, P., Caprile, B., Ajelli, M., Pugliese, A., Merler, S.: J. Theor. Biol. 260, 31 (2009)

Poletti, P., Ajelli, M., Merler, S.: PLoS ONE 6, e16460 (2011)

Reluga, T.: J. Biol. Dynamics 3, 515 (2009)

Reluga, T.: PLoS Comput. Biol. 6, e1000793 (2010)

Reluga, T., Galvani, A.P.: Math. Biosci. 230, 67 (2011)

Reluga, T., Bauch, C.T., Galvani, A.: Math. Biosci. 204, 185 (2006)

Rizzo, C., Rota, M.C., Bella, A., Giannitelli, S., De Santis, S., et al.: Euro Surveill. 15, 49 (2010)

Ross, R.: Proc. Royal Soc. London 92, 204 (1916)

Salathe, M., Bonhoeffer, S.: J. Roy. Soc. Interface 5, 1505 (2008)

Salmon, D.A., Teret, S.P., MacIntyre, C.R., Salisbury, D., Burgess, M.A., et al.: Lancet 367, 436 (2006)

Scalia-Tomba, G.: Math. Biosci. 107, 547 (1991)

Scudo, F.M., Ziegler, J.R.: The golden age of theoretical ecology: 1923–1940. Lecture Notes Biomathematics, vol. 22. Springer, Berlin (1978)

Shaw, L.B., Schwartz, I.B.: Phys. Rev. E 77, 066101 (2008)

Shim, E., Chapman, G.B., Townsend, J.P., Galvani, A.P.: J. Roy. Soc. Interface 9, 2234 (2012)

Smith, D.L., Levin, S.A., Laxminarayan, R.: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 3153 (2005)

Solomon, J., Murray, C.J.L.: Popul. Dev. Rev. 28, 205 (2002)

Staiano, J.: ESSAI: 6 (2008). http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol6/iss1/46(lastvisit24/10/2012).

Sterman, J.: Am. J. Public Health 96, 505 (2006)

Stigum, H., Magnus P., Bakketeig L.S.: Am. J. Epidemiol. 145, 644 (1997)

Sun, P., Yang, L., de Vericourt, F.: Oper. Res. 57, 1320 (2009)

Tanaka, M.M., Kumm, J., Feldman, M.W.: Theor. Popul. Biol. 62, 111 (2002)

The Editors Of The Lancet “Retraction—Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children”. Lancet 375, 445 (2010) DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60175-4

United Nations: Changing Levels and Trends in Mortality: the role of patterns of death by cause. UN (2012)

Vardavas, R., Breban, R., Blower, S.: PLoS Comput. Biol. 3, e85 (2007)

Velasco-Hernandez, J.X., Hsieh, Y.: J. Math. Biol. 32, 233 (1994)

Velasco-Hernandez, J.X., Brauer, F., Castillo-Chavez, C.: IMA J. Math. Appl. Med. Biol. 13, 175 (1996)

Wolfe, R.M., Sharp, L.K.: Br. Med. J. 325, 430 (2002)

Zagheni, E., Billari, F.C., Manfredi, P., Melegaro, A., Mossong, J., et al.: Am. J. Epidemiol. 168, 1082 (2008)

Zanette, D., Risau-Gusman, S.: J. Biol. Phys. 34, 135 (2008)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2013 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Bauch, C., d’Onofrio, A., Manfredi, P. (2013). Behavioral Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases: An Overview. In: Manfredi, P., D'Onofrio, A. (eds) Modeling the Interplay Between Human Behavior and the Spread of Infectious Diseases. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5474-8_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5474-8_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-5473-1

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-5474-8

eBook Packages: Mathematics and StatisticsMathematics and Statistics (R0)