Abstract

Okay, so we’ve heard the case histories. What about academic studies of the question? Is there a consensus?

Access this chapter

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Notes

Neil J. Sullivan, “Major League Baseball and American Cities: A Strategy for Playing the Stadium Game,” in The Economics and Politics of Sports Facilities, p. 182.

Neil deMause and Joanna Cagan, Field of Schemes: How the Great Stadium Swindle Turns Public Money into Private Profit, p. xi.

Mark S. Rosentraub, Major League Losers: The Real Cost of Sports and Who’s Paying for It (New York: Basic Books, 1997), pp. 3–4.

“Average salary in baseball just over $3 million in 2010,” www.CBSSports.com, December 13, 2010.

Jarrett Bell, “NFL salaries: Top NFL QBs could be in line for contract hikes,” www.usatoday.com, March 9, 2010.

Andrew Brandt, “NBA draft picks come up short compared to NFL top rookies,” www.huffingtonpost.com, June 24, 2010.

Kurt Badenhausen, “The Highest-Paid NHL Players,” www.forbes.com, December 1, 2010.

“Household Income for States,” www.census.gov.

Robert A. Baade, “Evaluating Subsidies for Professional Sports in the United States and Europe: A Public-Sector Primer,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy: 595.

Tom Van Riper, “Football’s Billionaires,” www.forbes.com, October 1, 2010.

Robert A. Baade, “Home Field Advantage? Does the Metropolis or Neighborhood Derive Benefit from a Professional Sports Stadium?” in The Economics and Politics of Sports Facilities, pp. 85–86.

All net worths from Tom Van Riper, “Football’s Billionaires,” www.forbes.com.

Allen R. Sanderson, “Sports Facilities and Development: In Defense of New Sports Stadiums, Ballparks and Arenas,” Marquette Sports Law Journal, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Spring 2000): 174–75.

Dennis Zimmerman, “Subsidizing Stadiums,” in Sports, Jobs & Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums, p. 121.

Mayya M. Komisarchik and Aju J. Fenn, “Trends in Stadium and Arena Construction, 1995–2015,” unpaginated.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Carolyn A. Dehring, Craig A. Depken II, and Michael R. Ward, “The Impact of Stadium Announcements on Residential Property Values: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Dallas-Fort Worth,” Working Paper, 2006, p. 1.

Dennis Coates and Brad R. Humphreys, “The Stadium Gambit and Local Economic Development,” Regulation: 16.

James Quirk and Rodney D. Fort, Pay Dirt: The Business of Professional Sports Teams, p. xxiii–xxiv.

Ibid., p. 131.

John Crompton, “Beyond Economic Impact: An Alternative Rationale for the Public Subsidy of Major League Sports Facilities,” Journal of Sport Management: 41–42.

James Quirk and Rodney D. Fort, Pay Dirt: The Business of Professional Sports Teams, p. 127.

John L. Crompton, Dennis R. Howard, and Turgut Var, “Financing Major League Facilities: Status, Evolution and Conflicting Forces,” Journal of Sport Management: 168–69.

Andrew Moylan, “Stadiums and Subsidies: Home Run for Wealthy Team Owners, Strike-out for Taxpayers,” National Taxpayers Union Foundation, NTUF Policy Paper #163, October 30, 2007, p. 3.

Ibid., p. 5.

Judith Grant Long, “Full Count: The Real Cost of Public Funding for Major League Sports Facilities,” Journal of Sports Economics, Vol. 6, No. 2 (May 2005): 120.

Ibid.: 139.

Katherine C. Leone, “No Team, No Peace: Franchise Free Agency in the National Football League,” Columbia Law Review: n120.

Roger G. Noll and Andrew Zimbalist, “Build the Stadium. Create the Jobs!” in Sports, Jobs & Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums, p. 25.

John Siegfried and Andew Zimbalist, “The Economics of Sports Facilities and Their Communities,” Journal of Economic Perspectives: 100.

Edward I. Sidlow and Beth M. Henschen, “Building Ballparks: The Public-Policy Dimensions of Keeping the Game in Town,” in The Economics and Politics of Sports Facilities, p. 165.

Kevin J. Delany and Rick Eckstein, “The Devil Is in the Details: Neutralizing Critical Studies of Publicly Constructed Stadiums,” Critical Sociology, Vol. 29, No. 2 (2003): 203.

Dennis Coates and Brad R. Humphreys, “Do Economists Reach a Conclusion on Subsidies for Sports Franchises, Stadiums, and Mega-Events?” Econ Journal Watch: 296.

Ibid.: 301–302.

Mark S. Rosentraub, Major League Losers: The Real Cost of Sports and Who’s Paying for It, p. 149.

Richard Corliss, “Build It, and They (Will) MIGHT Come,” Time.

Alex Williams, “Back to the Future,” New York.

Dennis Coates and Brad R. Humphreys, “Caught Stealing: Debunking the Economic Case for D.C. Baseball,” pp. 5–7.

Mark S. Rosentraub and David Swindell, “’Just Say No?’ The Economic and Political Realities of a Small City’s Investment in Minor League Baseball,” Economic Development Quarterly, Vol. 5, No. 2 (May 1991): 154–55.

Steven A. Riess, Touching Base: Professional Baseball and American Culture in the Progressive Era, p. 111.

Robert A. Baade and Allen R. Sanderson, “The Employment Effect of Teams and Sports Facilities,” in Sports, Jobs & Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums, p. 93.

Robert A. Baade, “Stadiums, Professional Sports, and Economic Development: Assessing the Reality,” pp. 14–15.

Ibid., pp. 22–23.

Robert A. Baade and Richard F. Dye, “The Impact of Stadiums and Professional Sports on Metropolitan Area Development,” Growth and Change (Spring 1990): 1.

Ibid.: 13.

Ibid.: 12.

Drake Bennett, “Ballpark figures,” Boston Globe.

Dennis Coates and Brad R. Humphreys, “Do Economists Reach a Conclusion on Subsidies for Sports Franchises, Stadiums, and Mega-Events?” Econ Journal Watch: 305.

Phillip A. Miller, “The Economic Impact of Sports Stadium Construction: The Case of the Construction Industry in St. Louis, MO,” Journal of Urban Affairs, Vol. 24, No. 2 (2002): 159.

Ibid.: 161.

Ibid.: 159.

Ibid.: 160, 161.

Ibid.: 170.

Ian Hudson, “Bright Lights, Big City: Do Professional Sports Teams Increase Employment?” Journal of Urban Affairs, Vol. 21, No. 4 (1999): 397–407.

Dean V. Baim, The Sports Stadium as a Municipal Investment, p. 157.

Ibid., pp. 162–63.

Robert A. Baade, “Home Field Advantage? Does the Metropolis or Neighborhood Derive Benefit from a Professional Sports Stadium?” in The Economics and Politics of Sports Facilities, p. 88.

Robert A. Baade, “Stadiums, Professional Sports, and Economic Development: Assessing the Reality,” pp. 2, 3.

Roger G. Noll and Andrew Zimbalist, “The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Facilities,” in Sports, Jobs & Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums, p. 71.

John Siegfried and Andrew Zimbalist, “The Economics of Sports Facilities and Their Communities,” Journal of Economic Perspectives: 106.

Craig A. Depken II, “The Impact of New Stadiums on Professional Baseball Team Finances,” Public Finance and Management, Vol. 6, No. 3 (June 2006): 436.

Ibid.: 436, 446.

Carolyn A. Dehring, Craig A. Depken II, and Michael R. Ward, “The Impact of Stadium Announcements on Residential Property Values: Evidence from a Natural Experiment in Dallas-Fort Worth,” p. 13.

Robert A. Baade, “Home Field Advantage? Does the Metropolis or Neighborhood Derive Benefit from a Professional Sports Stadium?” in The Economics and Politics of Sports Facilities, pp. 74, 78.

John C. Melaniphy, “The Impact of Stadiums and Arenas,” Real Estate Issues: 37.

Ibid.: 38.

Richard Pollard, “Evidence of a reduced home advantage when a team moves to a new stadium,” Journal of Sports Sciences (2002): 969.

Ibid.: 972.

Minor League Baseball and Local Economic Development, edited by Arthur T. Johnson (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995), p. 32.

Ibid., p. 249.

Mark S. Rosentraub and David Swindell, “’Just Say No?’ The Economic and Political Realities of a Small City’s Investment in Minor League Baseball,” Economic Development Quarterly: 152.

Ibid.: 154.

Drake Bennett, “Ballpark figures,” Boston Globe.

Mark S. Rosentraub and David Swindell, “’Just Say No?’ The Economic and Political Realities of a Small City’s Investment in Minor League Baseball,” Economic Development Quarterly: 164–65.

Drew Stone, “Introducing Parkview Field,” Fort Wayne News-Sentinel, September 12, 2008.

Victor A. Matheson and Robert A. Baade, “Have Public Finance Principles Been Shut Out in Financing New Sports Stadiums for the NFL in the United States?” College of the Holy Cross Department of Economics Faculty Research Series, Paper No. 05-11 (July 2005): 2.

Ibid.: 14.

Ibid.: 5.

Mayya M. Komisarchik and Aju J. Fenn, “Trends in Stadium and Arena Construction, 1995–2015.”

Neil deMause and Joanna Cagan, Field of Schemes: How the Great Stadium Swindle Turns Public Money into Private Profit, p. 84.

Veronica Z. Kalich, “A Public Choice Perspective on the Subsidization of Private Industry: A Case Study of Three Cities and Three Stadiums,” Journal of Urban Affairs: 212.

Rodney Fort, “Direct Democracy and the Stadium Mess,” in Sports, Jobs & Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums, p. 146.

Ibid., pp. 161–62.

Andrew Zimbalist, “The Economics of Stadiums, Teams and Cities,” in The Economics and Politics of Sports Facilities, p. 57.

Ibid., p. 58.

Mayya M. Komisarchik and Aju J. Fenn, “Trends in Stadium and Arena Construction, 1995–2015.”

Quoted in Neil deMause and Joanna Cagan, Field of Schemes: How the Great Stadium Swindle Turns Public Money into Private Profit, pp. 103–104.

Allen R. Sanderson, “Sports Facilities and Development: In Defense of New Sports Stadiums, Ballparks and Arenas”: 183–84.

Herbert J. Rubin, after a series of conversations with economic development officials in the Midwest, described the ravenously credit–hogging philosophy of economic development practitioners as “shoot anything that flies; claim anything that falls.” It doesn’t matter, really, whether or not the incentives or even outright gifts offered by those public officials charged with economic development were really the lures that brought a business to town, or that filled a square with tourists, or that replenished a city’s tax coffers: shoot and claim everything and let God (or an especially meticulous researcher) sort ’em out. Herbert J. Rubin, “Shoot Anything that Flies; Claim Anything that Falls: Conversations with Economic Development Practitioners,” Economic Development Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 3 (August 1988): 236–51.

Steven A. Riess, “Historical Perspectives on Sports and Public Policy,” in The Economics and Politics of Sports Facilities, p. 33.

Joseph L. Bast, “Sports Stadium Madness: Why It Started/How to Stop It,” p. 6.

William J. Hunter, “Economic Impact Studies: Inaccurate, Misleading, and Unnecessary,” Heartland Institute Policy Paper No. 21, July 22, 1988, p. 6.

John Crompton, “Beyond Economic Impact: An Alternative Rationale for the Public Subsidy of Major League Sports Facilities,” Journal of Sport Management: 48.

Robert A. Baade, “Stadiums, Professional Sports, and Economic Development: Assessing the Reality,” pp. 7–8.

Jordan Rappaport and Chad Wilkerson, “What Are the Benefits of Hosting a Major League Sports Franchise?” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review (First Quarter 2001): 59, 63.

John Siegfried and Andrew Zimbalist, “The Economics of Sports Facilities and Their Communities,” Journal of Economic Perspectives: 104.

Kevin J. Delany and Rick Eckstein, “The Devil Is in the Details: Neutralizing Critical Studies of Publicly Constructed Stadiums,” Critical Sociology: 189.

Ibid.: 195.

Kevin J. Delany and Rick Eckstein, “The Devil Is in the Details: Neutralizing Critical Studies of Publicly Constructed Stadiums,” Critical Sociology: 197.

Ibid.: 197–98.

Ibid.: 199.

John Siegfried and Andrew Zimbalist, “The Economics of Sports Facilities and Their Communities,” Journal of Economic Perspectives: 105.

Kevin J. Delany and Rick Eckstein, “The Devil Is in the Details: Neutralizing Critical Studies of Publicly Constructed Stadiums,” Critical Sociology: 206–207.

Ibid.: 200.

Ibid.: 201.

Ibid.: 202, 205, 206, 208.

Quoted in Mark S. Rosentraub, Major League Losers: The Real Cost of Sports and Who’s Paying for It, p. 63.

Quoted in John Crompton, “Beyond Economic Impact: An Alternative Rationale for the Public Subsidy of Major League Sports Facilities,” Journal of Sport Management: 43–44.

Mark S. Rosentraub, Major League Losers: The Real Cost of Sports and Who’s Paying for It, p. 129.

Charles C. Euchner, Playing the Field: Why Sports Teams Move and Cities Fight to Keep Them, p. 55.

Ibid., p. 5.

Allen R. Sanderson, “Sports Facilities and Development: In Defense of New Sports Stadiums, Ballparks and Arenas”: 190.

Robert A. Baade, “Stadiums, Professional Sports, and Economic Development: Assessing the Reality,” p. 5.

Bruce K. Johnson and John C. Whitehead, “Value of Public Goods from Sports Stadiums: The CVM Approach,” Contemporary Economic Policy, Vol. 18, No. 1 (January 2000): 52.

Jordan Rappaport and Chad Wilkerson, “What Are the Benefits of Hosting a Major League Sports Franchise?” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review: 72.

John Crompton, “Beyond Economic Impact: An Alternative Rationale for the Public Subsidy of Major League Sports Facilities,” Journal of Sport Management: 42.

Ibid.: 50.

Ibid.: 55.

Richard Corliss, “Build It, and They (Will) MIGHT Come,” Time.

Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore, Inc. v. National League of Professional Baseball Clubs, Et al., Supreme Court of the United States, Argued April 19, 1922, Decided May 29, 1922, 259 U.S. 200.

Harold Seymour, Baseball: The People’s Game (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 131.

Neal R. Pierce, “Sports Blackmail: ‘Just Say No’?” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 26, 1997.

Richard Justice, “Union’s Fehr Says Owners Stand Against Expansion,” Washington Post, March 5, 1989.

George H. Sage, “Stealing Home: Political, Economic, and Media Power and a Publicly-Funded Baseball Stadium in Denver,” Journal of Sport and Social Issues: 112.

Katherine C. Leone, “No Team, No Peace: Franchise Free Agency in the National Football League,” Columbia Law Review: 473.

Ibid.: 520.

Ibid.: 512.

Joseph L. Bast, “Sports Stadium Madness: Why It Started/How to Stop It,” p. 40.

Lynn Reynolds Hartel, “Community-Based Ownership of a National Football League Franchise: The Answer to Relocation and Taxpayer Financing of NFL Teams,” Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Journal, Vol. 18 (1998): 593–94.

Ibid.

Ibid.: 592.

Ibid.: 604–605.

Ibid.: 611–12.

Joseph L. Bast, “Sports Stadium Madness: Why It Started/How to Stop It,” p. 2.

Lynn Reynolds Hartel, “Community-Based Ownership of a National Football League Franchise: The Answer to Relocation and Taxpayer Financing of NFL Teams,” Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Journal: 602.

Quoted in Joseph L. Bast, “Sports Stadium Madness: Why It Started/How to Stop It,” p. 41.

Lynn Reynolds Hartel, “Community-Based Ownership of a National Football League Franchise: The Answer to Relocation and Taxpayer Financing of NFL Teams,” Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Journal: 602.

Ibid.: 623, 628.

Mayya M. Komisarchik and Aju J. Fenn, “Trends in Stadium and Arena Construction, 1995–2015.”

Neil J. Sullivan, The Dodgers Move West, p. 215.

Arthur T. Johnson, “Municipal Administration and the Sports Franchise Relocation Issue,” Public Administration Review: 526.

Mark S. Rosentraub, Major League Losers: The Real Cost of Sports and Who’s Paying for It, p. 463.

Roger G. Noll and Andrew Zimbalist, “Are New Stadiums Worth the Cost?” Brookings Review Vol. 15, No. 3 (Summer 1997).

Roger G. Noll and Andrew Zimbalist, “Sports, Jobs, and Taxes: The Real Connection,” in Sports, Jobs & Taxes: The Economic Impact of Sports Teams and Stadiums, pp. 506–507.

Neal R. Pierce, “Sports Blackmail: ‘Just Say No’?” Cleveland Plain Dealer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

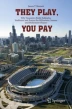

Bennett, J.T. (2012). If You Build It, Prosperity Will Not Come: What the Studies Say. In: They Play, You Pay. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3332-3_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3332-3_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4614-3331-6

Online ISBN: 978-1-4614-3332-3

eBook Packages: Business and EconomicsEconomics and Finance (R0)