Abstract

When systematic research on phobias began, fears related to specific objects or situations were still called “simple phobias” (see Marks, 1969), a term that misleadingly implied that these phobias were of low severity. In fact, specific phobias can incur serious life impairment, in the range of other mental disorders (Becker et al., 2007). Since the introduction of DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), they are listed by the preferable term specific phobias (see Hofmann, Alpers, & Pauli, 2009).

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Treatment Complications in Specific Phobias

When systematic research on phobias began, fears related to specific objects or situations were still called “simple phobias” (see Marks, 1969), a term that misleadingly implied that these phobias were of low severity. In fact, specific phobias can incur serious life impairment, in the range of other mental disorders (Becker et al., 2007). Since the introduction of DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), they are listed by the preferable term specific phobias (see Hofmann, Alpers, & Pauli, 2009).

Specific phobia is characterized by intense and persistent fear cued by exposure to, or anticipation of, a clearly discernible and circumscribed object or situation such as certain animals or insects, blood/injury/injection (BII), natural environmental events (e.g., thunder), or other stimuli (e.g., vomiting, contracting an illness). Although adults with phobias realize that these fears are irrational, they avoid confrontation in order to avoid triggering panic or severe anxiety. If the fear is confronted, it is common to experience emotional discomfort and marked autonomic, respiratory, and endocrine reactivity (Alpers, Abelson, Wilhelm, & Roth, 2003; Alpers & Sell, 2008; Alpers, Wilhelm, & Roth, 2005). Some symptoms are specific to certain fears, such as body sway, which is closely associated with fear of heights (Alpers & Adolph, 2008; Hüweler, Kandil, Alpers, & Gerlach, 2009).

The DSM-IV (APA, 1994) lists five discrete subtypes of specific phobias: (1) animal type: if the fear is cued by animals or insects; (2) natural environment type: if the fear is cued by objects in the natural environment, such as storms, heights, or water; (3) BII type: if the fear is cued by seeing blood or an injury or by receiving an injection or other invasive medical procedure; (4) situational type: if the fear is cued by a specific situation such as public transportation, tunnels, bridges, elevators, flying, driving, or enclosed places; and (5) other types: if the fear is cued by other stimuli (including choking, vomiting, or contracting an illness, fear of falling, and children’s fears of loud sounds or costumed characters).

Previous studies estimated the lifetime prevalence of specific phobias to be between 1% and 19% of the population. More recent data suggest that the lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates of specific phobia are about 13% and 9%, respectively (Becker et al., 2007; Kessler et al., 2005; Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005; Stinson et al., 2007). These data suggest that specific phobia is the most common form of anxiety disorder. Prevalence rates are generally higher in women than in men (ratios vary between 2:1 and 4:1 from study to study) with much variance between subtypes of phobias (Becker et al., 2007; Bourdon, Boyd, Rae, & Burns, 1988; Curtis, Magee, Eaton, Wittchen, & Kessler, 1998; Fredrikson, Annas, Fischer, & Wik, 1996; Stinson et al., 2007). The highest prevalence rates have been found for specific animal phobias in women and claustrophobia in men (Curtis et al., 1998). Prevalence rates also differ with ethnicity; the rates of specific phobias are almost twice as high in African-American individuals (Eaton, Dryman, & Weissman, 1991; Stinson et al., 2007). Considerable variation in prevalence rates can be found between cultures worldwide (Good & Kleinman, 1985; Shen et al., 2006).

Impairment has been found to strongly correlate with the number of phobic symptoms a patient experiences (Curtis et al., 1998). In addition to the high prevalence of multiple phobias, comorbidity with other mental disorders is high: 84% of all phobic patients have one or more comorbid disorders. Aside from other anxiety disorders, affective disorders and substance-related disorders are common (Kushner, Krueger, Frye, & Peterson, 2008). The phobia more often preceded (in 57% of the cases) the comorbid disorder (Magee, Eaton, Wittchen, McGonagle, & Kessler, 1996). In spite of the high prevalence and considerable impairment, only 8% reported treatment specifically for specific phobia (Stinson et al., 2007).

1.1 The Origin of Specific Phobias

Rachman (1977) suggested that there are three routes to develop a phobia: First, by classical conditioning due to a traumatic experience in a specific situation or in the presence of a specific object; second, by vicarious learning; and third, by instruction (usually the parents) or information (e.g., the media). Empirical data suggest that specific phobia develops following a traumatic experience in 36% of the cases, the observation of fearful behavior or observation of a trauma to others in 8%, and the instruction by others in 8%. This means that about 50% of the phobic patients do not recall how or why they developed the phobia (Kendler, Myers, & Prescott, 2002).

A number of longitudinal studies clearly demonstrate the link between traumatic experiences, such as traffic accidents or episodes of unexpected panic, and the later development of a specific phobia (Blaszczynski et al., 1998). Although these data show that some phobias date back to aversive experiences, this does not explain why certain classes of typical cues (e.g., spiders and snakes) often elicit phobic reactions despite rarely inflicting harm, while others often inflict harm (e.g., knives) but are rarely feared. This seeming paradox can be explained if one assumes that the typical phobic cues are prepared fear stimuli (Seligman, 1971). Indeed, several experiments consistently confirmed that fear responses conditioned to typical fear cues are more resistant to extinction (Mineka & Öhman, 2002). Also, vicarious learning of fear responses that has been documented for laboratory-reared monkeys who learned to avoid snakes from a model (Mineka, Davidson, Cook, & Keir, 1984) seems to be preparedness for evolutionary relevant fear cues (Cook & Mineka, 1989).

Based on the resistance to extinction documented for experimentally acquired responses, the preparedness hypothesis has been widely accepted and entered almost every textbook on biological and on abnormal psychology, although evidence for other characteristics of preparedness (ease of acquisition, irrationality, and belongingness) is much more limited (McNally, 1987). The basic premise of the theory that preparedness helps to protect humans from dangerous predators has recently been questioned for a common specific phobia, i.e., spider phobia (Gerdes, Uhl, & Alpers, 2009).

In humans learning avoidance behavior from models (Gerull & Rapee, 2002) and fear acquisition by instruction (Field & Lawson, 2003) seem to be particularly important routes to the development of anxiety. Moreover, it has been shown in longitudinal studies that experience with certain challenges such as heights or water is needed to unlearn certain inborn fears (Poulton & Menzies, 2002).

Theoretically, the characteristic avoidance behavior phobic patients display can be explained by the two-factor model (Mowrer, 1947). This model assumes that classically conditioned fear stimuli elicit a fear response that is then reduced or ameliorated by the instrumental avoidance behavior. The conclusion that this dysfunctional avoidance helps to maintain the fear response can be extended to fears acquired through other routes than classical conditioning. Aside from these learning-based considerations of how phobias may be acquired, there is strong evidence for a significant genetic disposition to acquire an anxiety disorder (Kendler, Neale, Kessler, Heath, & Eaves, 1992).

1.2 Differential Diagnosis and Comorbidity

A challenge to adequate differential diagnosis is the fact that anxiety disorders are highly comorbid (Brown, Campbell, Lehman, Grisham, & Mancill, 2001; Stinson et al., 2007). However, structured interviews such as the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV and adequate training in its application lead to good diagnostic accuracy and interrater reliability for specific phobias (Brown, Di Nardo, Lehman, & Campbell, 2001). Although most subtypes of phobic disorder can also be differentiated reliably (Fyer et al., 1989), a major difficulty is the diagnostic distinction of phobias and panic disorder. With the exception of phobias of the animal type, panic disorder patients – especially those with marked agoraphobia – often fear typical phobic cues such as heights, invasive medical procedures, public transportation, or contracting illness. Moreover, patients with specific phobias often experience panic attacks with marked physical symptoms during exposure to the feared cues, especially in the situational subtype (Ehlers, Hofmann, Herda, & Roth, 1994; Lipsitz, Barlow, Mannuzza, Hofmann, & Fyer, 2002). Symptoms of these situational panic attacks markedly overlap with typical symptoms experienced by panic disorder patients (Craske, 1991); for example, the symptom profile of the phobic fear of enclosed places is most similar to that of panic disorder and the fear of enclosed places is frequent in panic disorder patients. A further complication arises because the phobias trace back to a spontaneous panic attack in many patients (Himle, Crystal, Curtis, & Fluent, 1991). In spite of these similarities, phobic fear and panic disorder are clearly distinguished by most theoretical accounts because they are either uncued (i.e., as seen in panic disorder) or cued (i.e., as seen in specific phobia) (Barlow, 2002).

1.3 Gold Standard for Therapy: Exposure

A systematic review of treatment studies published between 1960 and 2005 shows that research has been conducted on the usefulness of systematic desensitization (or imaginal exposure), in vivo exposure, cognitive therapy, for a multitude of different specific phobias and applied tension for BII phobia specifically (Choy, Fyer, & Lipsitz, 2007). The limited data on medication are disappointing (Choy et al., 2007).

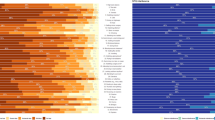

Although some textbooks still recommend systematic desensitization (Wolpe, 1962) as the typical strategy for the treatment of phobias, today, the gold standard for the treatment of specific phobias clearly is exposure therapy unaccompanied by relaxation instruction. Response to in vivo exposure has proven to be superior to systematic desensitization in several direct comparisons (Choy et al., 2007). The effects of exposure are generally not limited to behavioral changes but extend to improvement in cognitive measures of fear as well (Booth & Rachman, 1992). Figure 1 illustrates extinction of self-reported fear and heart rate within and across repeated exposure sessions in a claustrophobic patient.

Self-reported fear (subjective units of distress, SUD) and heart rate (HR) in one selected patient in the course of the six exposure sessions. The patient was 52 years of age. His HR at quiet sitting after session 6 was 64 bpm. His scores on a claustrophobia questionnaire (CLQ, Radomsky, Rachman, Thordarson, McIsaac, & Teachman, 2001) changed from 57 before to 28 after the sixth session (with permission from Alpers & Sell, 2008)

1.4 Efficacy of Exposure

A recent meta-analysis systematically compared the efficacy of different strategies used to treat specific phobias (Wolitzky-Taylor, Horowitz, Powers, & Telch, 2008). Data from 33 randomized treatment studies were compared. First, exposure-based treatment approaches produced large effect sizes relative to no treatment (wait list). Second, exposure also outperformed placebo conditions and alternative active psychotherapeutic approaches (e.g., relaxation training). Third, in vivo exposure with the phobic cue also outperformed alternative forms of exposure therapy (e.g., imaginal exposure, virtual reality) at post-treatment. There are now several well-established manuals providing self-help materials as well as support and information for the clinician (e.g., Barlow & Craske, 1994; Bourne, 1998, 2005). In vivo exposure is often conducted in a graded fashion, beginning with a relatively mild challenge and progressively moving upward on the hierarchy of fearful cues.

A review of studies using in vivo exposure therapy reported that between 80% and 90% of treatment completers were able to complete the behavioral avoidance task, a measure of clinically significant change, at the end of treatment (Choy et al., 2007). The difference between treatments was sometimes as large as 25% of completers being able to touch a snake after systematic desensitization versus 92% after in vivo exposure (Bandura, Blanchard, & Ritter, 1969). Importantly, there has been no evidence for symptom substitution. Instead, the gains obviously generalized to other domains, even to those not addressed during exposure treatment (Götestam & Götestam, 1998).

Follow-up assessments of in vivo exposure were gathered for several specific phobias with periods ranging from 6 months to 14 months. In general, treatment gains are either maintained or further improved over time (Choy et al., 2007). However, superiority of in vivo exposure to alternative approaches was less pronounced in some studies at follow-up than at the post-treatment assessment following exposure therapy (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008). For both findings (the increasing effects and the decline of treatment-specific differences) a possible explanation may be that even moderate therapeutic improvement may motivate all patients to engage in self-guided in vivo exposure so that they can improve further. On the other hand, some patients who were successfully treated with in vivo exposure may cease to self-expose after treatment has terminated and may return to some of their avoidance behavior. In the clinical setting, this needs to be assessed in booster sessions on an individual basis. The few studies that examined very long-term outcomes call for caution. Lipsitz and colleagues reassessed symptoms 10–16 years after treatment and found considerable rates of relapse (Lipsitz, Mannuzza, Klein, Ross, & Fyer, 1999).

Interestingly, very brief exposure treatments have garnered substantial support. For example, Öst and coworkers have demonstrated that prolonged exposure can be successful even if there is only one extended session (usually between 2 h and 4 h) with a therapist (Öst, 1989). The effectiveness has been demonstrated most clearly for small animal phobias (Gotestam, 2002; Hellstroem & Oest, 1995; Koch, Spates, & Himle, 2004; Thorpe & Salkovskis, 1997) and flying phobia (Öst, Brandberg, & Alm, 1997). However, in the meta-analysis mentioned before (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008), multi-session treatments marginally outperformed single-session treatments on domain-specific questionnaire measures of phobic dysfunction, and moderator analyses revealed that more sessions predicted more favorable outcomes.

Although it is often assumed that some phobias may be more difficult to treat than others, effect sizes for the major comparisons of interest were not moderated by the type of specific phobia in the meta-analysis (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008). Interestingly, the meta-analysis also revealed that placebo treatments were significantly more effective than no treatment, which suggests that patients with specific phobias are moderately responsive to placebo interventions.

Although beyond the scope of this chapter, it should be mentioned that phobias are common in children as well. Although their characteristics often differ from those in adults, there is some overlap. Because phobias start early in life, and pose a risk for developing a second mental disorder, and because of the chronic duration, the need for treatment in childhood and adolescence is obvious (Becker et al., 2007). Exposure in vivo is also the treatment of choice for small animal phobias in children (Muris, Merckelbach, Holdrinet, & Sijsenaar, 1998).

2 Core Elements of CBT

2.1 Cognitive Preparation or Psychoeducation

Most treatment approaches for specific phobias include some form of psychoeducation, but the core CBT strategy to overcome phobic fear is unanimously some variant of exposure and response prevention. In this context, psychoeducation has the purpose of introducing the therapeutic rationale, and typically addresses the nature of (non-clinical) fear and its protective function. It usually also involves a review of the individual’s risk assessment in a given situation and some cognitive restructuring if this assessment seems to be exaggerated. Then, the principles of fear acquisition and extinction are reviewed, with the purpose of raising motivation and clarifying expectations for the exposure therapy to follow. Together, these aspects of psychoeducation are sometimes summarized as cognitive preparation. Significant predictors of treatment success are credibility of the treatment rationale and the motivation for psychotherapy in general (e.g., Öst, Stridh, & Wolf, 1998; Southworth & Kirsch, 1988).

2.2 Exposure to Fear Cues

In the preparation for exposure therapy, patients are asked to identify and arrange cues that evoke undue fear from the least to the most frightening. Starting at a cue representing moderate fear, patients are asked to gradually expose themselves to the cue, usually for up to an hour or more at a time, allowing ensuing feelings and thoughts to occur without escape, and to continue the exposure until these feelings of discomfort subside. Such homework is frequently assigned on a daily basis. Exposure may be conducted with or without a therapist (e.g., Öst et al., 1998) and/or guided by appropriate self-help books or computer systems (e.g., Kenwright, Marks, Gega, & Mataix-Cols, 2004). Phobic cues are frequently live situations or objects, but when difficult to arrange, pictures, film material, or computer animations (see Virtual Reality) or imaginal stimuli may be used. A number of studies now suggest that virtual reality may be effective in flying and height phobia, but this needs to be substantiated by more controlled trials (Choy et al., 2007; Krijn, Emmelkamp, Olafsson, & Biemond, 2004; Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2008).

2.3 A Case Example: Treating Spider Phobia

Jen, aged 35, consulted a therapist for her severely handicapping and inexplicable fear of spiders. She had never really liked spiders and her fear had intensified over the years. Whenever she saw a spider she panicked helplessly and felt frozen in place. Her heart raced, her palms sweated, and she felt embarrassed because she depended on other people because of this fear. She avoided walking across a lawn or going into her basement or garage lest she encountered spiders there. Having unsuccessfully tried to prevent spiders entering her home, she was about to move elsewhere. Jen was told her symptoms were typical of a phobia and that she could endure them for long enough to get used to whatever was frightening her. Even the mere thought of looking at a spider evoked extreme fear and disgust. In therapy, she learned to open a book with pictures of spiders in the therapist’s office. She took the book home and made herself touch the pictures with her fingers. Next, she looked at a spider in an empty glass jar for at least 30 min without her usual attempt to remove it or turn away from it. Jen was encouraged to do exposure without her usual subtle avoidances that stopped her experiencing the fear fully and getting used to it. Thus she examined the spider and her own reactions in detail, she was fascinated at not being overwhelmed by fear. Her distress decreased during each exposure session and across repeated such sessions. She became more confident exposing herself to spiders at home. After 10–50 min weekly sessions and several hours of practice at home she touched a large spider and let it crawl across her palm. When she had accomplished this, she expressed doubt that her family would actually believe what she had just done, and the therapist spontaneously decided to take a few pictures of how she handled the spider. She was proud and happy to take home her therapy graduation pictures. Jen then cleaned out her garage, kept a spider in a jar in her kitchen, and went to bed without checking for spiders. Improvement continued at follow-up 8 weeks later.

3 Factors that May Interfere with Exposure Success

3.1 Treatment Engagement

As in CBT for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia (see Sanderson & Bruce, 2007), lack of engagement in behavioral exposure or non-compliance is the most important reason for sub-optimal treatment response in phobia therapy as well. For example, compliance with self-exposure homework during weeks 0–8 predicted more improvement 2 years later (Park et al., 2001). An older and relatively small study suggests that positive interaction (“warm therapist behavior”) contributes to better adherence (Morris & Magrath, 1979). Even in completed treatments, negative cognitions have been identified as a predictor of poor treatment response (Rachman & Levitt, 1988; Shafran, Booth, & Rachman, 1993). Accordingly, cognitive interventions should be considered to address possible negative expectations, as a strategy to reduce drop-out and to improve outcome. It is important to point out that patients who fail to improve with one treatment, for example, relaxation training, retain a strong chance of responding after subsequent crossover to exposure therapy (Park et al., 2001).

3.2 Duration of Exposure

Generally, clinicians strongly emphasize that exposure sessions need to be of adequate duration to result in a reduction of fear across sessions. Exposure appears to be more effective as the patient is given more time to experience the reduction of anxiety in the presence of the phobic cue. For example, exposure was found to be more effective when no anxiety was experienced for at least 1 min compared to a condition where exposure was ended when the highest level of anxiety was reached (Marshall, 1985). Likewise, longer exposure results in more fear extinction than shorter exposures even if the total duration of exposure is held constant (Stern & Marks, 1973; but see de Silva & Rachman, 1984). Several studies with fixed durations (e.g., 30 min) of exposure have also been found to be effective independent of fear levels (e.g., Alpers et al., 2005); the most crucial aspect of these repeated brief exposures may be that patients are taught that they will have to return to exposure soon after the first exposure has terminated, even if it was terminated at a relatively high level of anxiety.

3.3 Multiple Phobias

When more than one situation or object is feared, which is quite typical (Hofmann, Lehman, & Barlow, 1997; Stinson et al., 2007), patient and therapist need to decide which fear to target first. If too many issues are targeted at the same time it may be difficult for the patient to monitor gradual change in the course of the intervention. As such, one recommendation is that extinction should be clearly observable in the course of exposure exercises with one situation before targeting the next task.

Often, there are several distinct facets to one specific phobia. For example, in some cases with driving phobia it makes a big difference whether the patient is the driver or a passenger (Alpers et al., 2005; Ehlers et al., 1994). Exposure exercises will have to target these specific circumstances; the patient will have to be the driver or the passenger. Similarly, if patients with such a specific phobia experience panic attacks while driving, they may be very concerned that these attacks might impair their ability to drive. Here, cognitive restructuring will have to address these risk estimations (see below). On top of this, the car is a confined space that cannot be left at any time, that is, claustrophobia may make things worse. As indicated above, this aspect can be targeted separately. While driving, the driver might be exposed to unpleasant temperatures or lighting conditions or dizziness – intolerance of unpleasant bodily experiences, i.e., anxiety sensitivity may contribute to symptom development. Specific interventions targeting interoceptive exposure (Antony, Ledley, Liss, & Swinson, 2006) may be indicated to treat fear of bodily sensations. Also, while driving one is exposed to being far away from home when driving long distances – a typical agoraphobic challenge that can be the topic of a homework exercise even when the patient is not prepared to drive yet. When there are different facets to a specific phobia, the different circumstances and conditions need to be thoroughly explored and evaluated. Any case formulation will have to take these patient-specific factors into account.

3.4 When Other Unpleasant Emotions/Sensations Come into Play

Disgust. Although the characteristic emotional experience in phobias is fear upon exposure to the phobic cue, some cues may also elicit the distinct emotion disgust (Davey, 1994; Woody, McLean, & Klassen, 2005), which seems to change with therapy on different gradients (Smits, Telch, & Randall, 2002). Disgust also decreases during exposure treatment. However, in one study, the decline of disgust ratings was found to lag behind that of fear ratings in a direct comparison (Smits et al., 2002). Interestingly, disgust levels at pretreatment did not moderate the level of fear activation or fear reduction during treatment in this study. Although an experimental analysis seems to indicate that disgust does not have a strong influence on the return of fear (Edwards & Salkovskis, 2006), the observation that not all emotions extinguish at the same rate may be relevant for treatment. The goal of exposure may not only be to reduce fear but also to reduce the level of other unpleasant emotions.

Nausea. Nausea is frequently related to anxiety disorders (Haug, Mykletun, & Dahl, 2002). More specifically, the fear of vomiting can make it difficult for a patient to expose herself to fear-provoking cues. Research with patients who are specifically afraid of vomiting (i.e., emetophobia) suggests that this fear may be closely related to the fear of losing control, and that vomiting phobia reflects this underlying problem (Davidson, Boyle, & Lauchlan, 2008). Such a fear of losing control should be explored and targeted by specific cognitive interventions which are aimed at increasing the tolerance of uncertainty (see Keefer et al., 2005; Robichaud & Dugas, 2006). There is evidence from a few case reports that also other worries about gastrointestinal problems, such as being afraid of having diarrhea (Hedberg, 1973) or excessive need to urinate (Myers, MacKinnon, & Corson, 1982), have been successfully treated with behavioral interventions. Physical therapy with vestibular rehabilitation exercises may benefit phobic patients with vestibular dysfunctions (Jacob, Whitney, Detweiler-Shostak, & Furman, 2001).

Lightheadedness/Fainting. Related to disgust and nausea is the fear of BII. Patients with BII phobia often faint when exposed to the relevant cues (Dahlloef & Öst, 1998; Sarlo, Buodo, Munafo, Stegagno, & Palomba, 2008). This particular psychophysiological pattern has been addressed in a specific intervention, applied tension (Öst, Fellenius, & Sterner, 1991; Öst, Lindahl, Sterner, & Jerremalm, 1984; Öst & Sterner, 1987).

Shame. Patients with a specific phobia can feel utterly debilitated as a consequence of their fear. They are dependent on family members and friends. In many cases they have to tailor their job search around conditions allowing them to avoid whatever they are afraid of. As in cases of social anxiety disorder, the focus of maladaptive cognitions can be placed on the consequence of public scrutiny and subsequent negative evaluation (“I’m going to make a fool of myself”). Some treatment strategies can also result in embarrassment (e.g., riding an elevator up and down for extended periods of time or staying in small fitting rooms while other people rush through the department store). This needs to be addressed when exposure is planned or it may result in undue insecurity or early cessation of prolonged exposure. Importantly, the patient needs to be aware of the different emotions aroused in a given situation (i.e., claustrophobic fear versus embarrassment because the exercises may draw passengers’ attention).

3.5 When Skill Deficits Accompany the Phobia

Longstanding phobias (with onset in childhood) – phobias of animals, the natural environment, and BII type often start in childhood while most situational phobias usually start in early adulthood (e.g., Becker et al., 2007; Lipsitz et al., 2002) – may have prevented development of appropriate skills for the phobic situation. For example, individuals with longstanding fears of dogs may not have developed skills for appropriately interacting with animals, and may require training in how to approach, touch, or interact with an animal (e.g., Rentz, Powers, Smits, Cougle, & Telch, 2003). Similar considerations are apt for driving fears, where the therapist should remain vigilant to poor driving habits which may both increase the fearfulness and the actual risk of the driving experience (see Taylor, Deane, & Podd, 2007).

3.6 When Anticipation Is Worse than Exposure

The maladaptive cognitions associated with the phobias tend to be future-oriented perceptions of danger or threat (e.g., what is about to happen, what will happen). This sense of danger may involve either physical threat (e.g., having a heart attack) or psychological (e.g., anxiety focused on embarrassment). In addition, these cognitions tend to focus upon a sense of uncontrollability over the situation or symptoms of anxiety.

Related to the issue of risk assessments is the fact that anticipatory anxiety is often worse than fear during exposure. A striking overprediction of fear before the exposure compared to the limited increase in fear during the exposure itself has frequently been observed (Alpers & Sell, 2008; Johansson & Oest, 1982; Rachman & Bichard, 1988).

In a study with a height exposure task in a theme park we showed that, for all participants, fear, dizziness, and body sway were increased during exposure (Alpers & Adolph, 2008). However, anticipated fear most reliably predicted body sway during exposure. In addition, persons scoring high on trait fear of heights anticipated and experienced more fear during exposure, but this relationship was not found for any objective measure.

Attending to overestimations in the likelihood of catastrophic events is one way of addressing these anticipatory fears. A focus on danger or harm is most frequently associated with the natural environment and situational subtypes (Lipsitz et al., 2002). Patients with a fear of flying may overestimate the risk of plane crashes, those with claustrophobia may exaggerate the risk of suffocation in an elevator, and those with the specific phobia of driving are often concerned with their own ability to drive. To help with anticipatory anxiety, patients may be asked to research facts about the feared situation prior to the initiation of exposure. This information is then applied in a cognitive-restructuring format to help patients generate more accurate expectations prior to exposure.

3.7 When Patients Use Cognitive Avoidance During Exposure

Even if patients agree to pursue exposure, this strategy may sometimes fail to result in a sizable extinction of fear responses. One reason is related to cognitive avoidance during exposure. Theoretically, avoidance or distraction should result in less extinction (Foa & Kozak, 1991, 1986; Rodriguez & Craske, 1993). This is supported by studies that found less treatment response in patients who were distracted from experiencing the full extent of fear during exposure (Grayson, Foa, & Steketee, 1982; Kamphuis & Telch, 2000; Mohlman & Zinbarg, 2000) or more return of fear (Haw & Dickerson, 1998). However, the detrimental effects of safety behavior (subtle avoidance strategies designed to reduce fear during exposure) have not always been replicated (Antony, McCabe, Leeuw, Sano, & Swinson, 2001; Milosevic & Radomsky, 2008).

In a recent study with claustrophobic patients it was evident that those who were encouraged to use safety behaviors during exposure showed significantly more fear at post-treatment and follow-up relative to those encouraged to focus and reevaluate their core threats during exposure (Sloan & Telch, 2002). Particularly during imaginal exposure, safety behavior is frequent and linked to poorer outcome (Rentz et al., 2003). Thus, patients should be instructed not to use subtle avoidance strategies and to fully experience the symptoms and feelings provoked by exposure.

3.8 Vigilance to Threat

Eysenck’s (1992) hypervigilance theory proposes that anxious people scan their environment excessively and broaden their attention span when searching for a fear-relevant stimulus and narrow it while that stimulus is processed. This hyperactive alarm system may lead to frequent and intense false alarms in fearful subjects (Becker & Rinck, 2004). The subsequent narrowing of attention may explain why patients have difficulties to disengage attention from spider distractors before moving on to the target. In contrast to several theoretical accounts, there is little evidence that attentional engagement to phobic cues actually occurs automatically (Alpers et al., 2009). Instead, patients with a spider phobia seem to have a deficit in disengaging their attention from spider cues (Gerdes, Alpers, & Pauli, 2008; Gerdes, Pauli, & Alpers, 2009). Under naturalistic conditions, phobic patients have also been shown to scan their environment for threatening stimuli (Lange, Tierney, Reinhardt-Rutland, & Vivekananda-Schmidt, 2004). Although specific interventions to address the dysfunctional allocation of attention are not yet available outside of the laboratory (see Mathews & MacLeod, 2002), patient behavior should be closely observed and observations such as excessive scanning should be addressed.

3.9 When Self-Report Is Not Predictive of Emotional Processing

Assessing verbal report during treatment is often not enough to assess emotional activation. Multiple response theory states that phobic fear is reflected in autonomic nervous system activation, self-report, and avoidance behavior (Lang, 1968). Despite the positive reaction this statement has created with theorists (e.g., Foa & Kozak, 1991), physiological measurement is often neglected, partly because its contribution of useful and unique information has not been convincingly documented. However, in a recent study we documented that although claustrophobic patients are activated both in self-report and in physiology while being exposed to a fear-related situation such as a small confined space, measuring heart rate can provide incremental information (Alpers & Sell, 2008). Although initial fear activation during exposure as indicated by self-report is not predictive of therapeutic change, higher heart rate responses to exposure correlate with more therapeutic change from before to after exposure treatment. Thus, whenever possible, physiological measurements should be consulted to monitor the effects of exposure treatment.

3.10 Enhancing Memory of Success

The return of fear in successfully treated patients is often thought of as a process similar to reinstatement of extinguished fear in the conditioning model (Bouton, 2002). To aid retention of exposure across the multiple contexts in which a phobic cue may be experienced in the future, extinction training in multiple contexts may be important (e.g., for animal work see Gunther, Denniston, & Miller, 1998). A superiority of variable context exposure training can also be observed in therapy with humans, especially in longer-term follow-up assessments (Vansteenwegen, Vervliet, Hermans, Thewissen, & Eelen, 2007; for review see also Craske et al., 2008). Hence, variability in the way in which exposure is conducted (in different settings, at different times of day, with and without therapist accompaniment) may aid longer-term fear reduction.

Also, there are now data suggesting that pharmacological cognitive enhancers (e.g., d-cycloserine) may increase the efficacy of exposure-based interventions in specific phobias (acrophobia Ressler, Rothbaum, Tannenbaum, Anderson, Graap, Zimand et al., 2004). Exposure therapy combined with d-cycloserine resulted in significantly larger reductions of acrophobia symptoms on all main outcome measures. Promising initial findings have also been reported for the augmentation of exposure therapy for claustrophobia with yohimbine, another putative cognitive enhancer for extinction learning (Powers, Smits, Otto, Sanders, & Emmelkamp, 2009). However, whether such adjunctive treatment with putative memory enhancers can help reduce the rate of treatment non-response to CBT has not been systematically evaluated.

4 Conclusion

It is appropriate that specific phobias are no longer called simple phobias. Specific phobias are highly prevalent and they can result in significant life impairment. The multitude of different fears and the considerable level of comorbidity imply that treatment needs to be individually tailored. There are several etiological pathways to the development of specific phobias and the individual’s learning history should be considered for treatment. Exposure and response prevention is the gold standard for treatment. Variants of this treatment approach have proven to be highly effective with lasting effects on multiple levels of responses (self-report, physiological reactivity, and behavioral avoidance). The specific ways in which exposure is conducted likely influences the robustness of outcome. This chapter attended to factors that need to be considered in planning and for adequate exposure situations, sufficient frequency, and duration of exposure exercises. Possible treatment complications, when other emotions come into play and when risk assessments call for specific interventions, were highlighted.

References

Alpers, G. W., Abelson, J. L., Wilhelm, F. H., & Roth, W. T. (2003). Salivary cortisol response during exposure treatment in driving phobics. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 679–687.

Alpers, G. W., & Adolph, D. (2008). Exposure to heights in a theme park: Fear, dizziness, and body sway. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 591–601.

Alpers, G. W., Gerdes, A. B. M., Lagarie, B., Tabbert, K., Vaitl, D., & Stark, R. (2009). Attention and amygdala activity: An fMRI study with spider pictures in spider phobia. Journal of Neural Transmission, 116(6), 747–757.

Alpers, G. W., & Sell, R. (2008). And yet they correlate: Psychophysiological measures predict the outcome of exposure therapy in claustrophobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22, 1101–1109.

Alpers, G. W., Wilhelm, F. H., & Roth, W. T. (2005). Psychophysiological assessment during exposure in driving phobic patients. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 126–139.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Antony, M. M., Ledley, D. R., Liss, A., & Swinson, R. P. (2006). Responses to symptom induction exercises in panic disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 85–98.

Antony, M. M., McCabe, R. E., Leeuw, I., Sano, N., & Swinson, R. P. (2001). Effect of distraction and coping style on in vivo exposure for specific phobia of spiders. Behavior Research and Therapy, 39, 1137–1150.

Bandura, A., Blanchard, E. B., & Ritter, B. (1969). Relative efficacy of desensitization and modeling approaches for inducing behavioral, affective, and attitudinal changes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13, 173–199.

Barlow, D. H. (2002). Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Barlow, D. H., & Craske, M. G. (1994). Mastery of Your Specific Phobia. Client Workbook (2nd ed.). San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation.

Becker, E. S., & Rinck, M. (2004). Sensitivity and response bias in fear of spiders. Cognition & Emotion, 18, 961–976.

Becker, E. S., Rinck, M., Turke, V., Kause, P., Goodwin, R., Neumer, S., et al. (2007). Epidemiology of specific phobia subtypes: Findings from the Dresden Mental Health Study. European Psychiatry, 22, 69–74.

Blaszczynski, A., Gordon, K., Silove, D., Sloane, D., Hillman, K., & Panasetis, P. (1998). Psychiatric morbidity following motor vehicle accidents: A review of methodological issues. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 39, 111–121.

Booth, R., & Rachman, S. (1992). The reduction of claustrophobia - I. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 30, 207–221.

Bourdon, K. H., Boyd, J. H., Rae, D. S., & Burns, B. J. (1988). Gender differences in phobias: Results of the ECA community survey. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 2, 227–241.

Bourne, E. J. (1998). Overcoming specific phobia: A hierarchy and exposure-based protocol for the treatment of all specific phobias. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Bourne, E. J. (2005). The anxiety & phobia workbook (4th ed.). xii, 432 pp. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Bouton, M. E. (2002). Context, ambiguity, and unlearning: sources of relapse after behavioral extinction. Biological Psychiatry, 52, 976–986.

Brown, T. A., Campbell, L. A., Lehman, C. L., Grisham, J. R., & Mancill, R. B. (2001). Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 585–599.

Brown, T. A., Di Nardo, P. A., Lehman, C. L., & Campbell, L. A. (2001). Reliability of DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: implications for the classification of emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 49–58.

Choy, Y., Fyer, A. J., & Lipsitz, J. D. (2007). Treatment of specific phobia in adults. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 266–286.

Cook, M., & Mineka, S. (1989). Observational conditioning of fear to fear-relevant versus fear-irrelevant stimuli in rhesus monkeys. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 98, 448–459.

Craske, M. G. (1991). Phobic fear and panic attacks: The same emotional states triggered by different cues? Clinical Psychology Review, 11, 599–620.

Craske, M. G., Kircanski, K., Zelikowsky, M., Mystkowski, J., Chowdhury, N., & Baker, A. (2008). Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 5–27.

Curtis, G. C., Magee, W. J., Eaton, W. W., Wittchen, H.-U., & Kessler, R. C. (1998). Specific fears and phobias: Epidemiology and classification. British Journal of Psychiatry, 173, 212–217.

Dahlloef, O., & Öst, L.-G. (1998). The diphasic reaction in blood phobic situations: Individually or stimulus bound? Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 27, 97–104.

Davey, G. C. L. (1994). The “disgusting” spider: The role of disease and illness in the perpetuation of fear of spiders. Society & Animals, 2, 17–25.

Davidson, A. L., Boyle, C., & Lauchlan, F. (2008). Scared to lose control? General and health locus of control in females with a phobia of vomiting. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 64, 30–39.

de Silva, P., & Rachman, S. (1984). Does escape behaviour strengthen agoraphobic avoidance? A preliminary study. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 22, 87–91.

Eaton, W. W., Dryman, A., & Weissman, M. M. (1991). Panic and phobia. In L. N. Robins & D. A. Regier (Eds.), Psychiatric disorders in America: The epidemiologic catchment area study (pp. 155–179). New York: Free Press.

Edwards, S., & Salkovskis, P. M. (2006). An experimental demonstration that fear, but not disgust, is associated with return of fear in phobias. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 20, 58–71.

Ehlers, A., Hofmann, S. G., Herda, C. A., & Roth, W. T. (1994). Clinical characteristics of driving phobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 8, 323–339.

Eysenck, M. W. (1992). Anxiety: The cognitive perspective. Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Field, A. P., & Lawson, J. (2003). Fear information and the development of fears during childhood: effects on implicit fear responses and behavioural avoidance. Behavior Research and Therapy, 41, 1277–1293.

Foa, E. B., & Kozak, M. J. (1991). Emotional processing: Theory, research, and clinical implications for anxiety disorders. In J. D. Safran & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), Emotion, psychotherapy, and change (pp. 21–49). New York: Guilford Press.

Foa, E. B., & Kozak, M. S. (1986). Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin, 99, 20–35.

Fredrikson, M., Annas, P., Fischer, H., & Wik, G. (1996). Gender and age differences in the prevalence of specific fears and phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 33–39.

Fyer, A. J., Mannuzza, S., Martin, L. Y., Gallops, M. S., Endicott, J., Schleyer, B., et al. (1989). Reliability of anxiety assessment. II. Symptom agreement. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46, 1102–1110.

Gerdes, A. B. M., Alpers, G. W., & Pauli, P. (2008). When spiders appear suddenly: spider-phobic patients are distracted by task-irrelevant spiders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 174–187.

Gerdes, A. B. M., Pauli, P., & Alpers, G. W. (2009). Toward and away from spiders: Eye-movements in spider-fearful participants. Journal of Neural Transmission, 116(6), 725–733.

Gerdes, A. B. M., Uhl, G., & Alpers, G. W. (2009). Spiders are special: Harmfulness does not explain why they are feared. Evolution and Human Behavior, 30, 66–73.

Gerull, F. C., & Rapee, R. M. (2002). Mother knows best: The effects of maternal modelling on the acquisition of fear and avoidance behaviour in toddlers. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 279–287.

Good, B. J., & Kleinman, A. M. (1985). Culture and anxiety: Cross-cultural evidence for the patterning of anxiety disorders. In A. H. Tuma & J. D. Maser (Eds.), Anxiety and the anxiety disorders (pp. 297–323). Hillsdale, NJ, England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gotestam, K. (2002). One session group treatment of spider phobia by direct or modelled exposure. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 31, 18–24.

Götestam, K. G., & Götestam, B. (1998). Process of change in exposure therapy of phobias. In E. Sanavio (Ed.), Behavior and cognitive therapy today: Essays in honor of Hans J. Eysenck (pp. 127–132). Oxford: Elsevier Science.

Grayson, J. B., Foa, E. B., & Steketee, G. (1982). Habituation during exposure treatment: Distraction versus attention-focusing. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 20, 323–328.

Gunther, L. M., Denniston, J. C., & Miller, R. R. (1998). Conducting exposure treatment in multiple contexts can prevent relapse. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 75–91.

Haug, T. T., Mykletun, A., & Dahl, A. A. (2002). The prevalence of nausea in the community: psychological, social and somatic factors. General Hospital Psychiatry, 24, 81–86.

Haw, J., & Dickerson, M. (1998). The effects of distraction on desensitization and reprocessing. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 765–769.

Hedberg, A. G. (1973). The treatment of chronic diarrhea by systematic desensitization: A case report. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 4, 67–68.

Hellstroem, K., & Oest, L.-G. (1995). One-session therapist directed exposure vs two forms of manual directed self-exposure in the treatment of spider phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 959–965.

Himle, J. A., Crystal, D., Curtis, G. C., & Fluent, T. E. (1991). Mode of onset of simple phobia subtypes: Further evidence of heterogeneity. Psychiatry Research, 36, 37–43.

Hofmann, S. G., Alpers, G. W., & Pauli, P. (2009). Phenomenology of panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. In M. M. Antony & M. B. Stein (Eds.), Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders (pp. 34–46). New York: Oxford University Press.

Hofmann, S. G., Lehman, C. L., & Barlow, D. H. (1997). How specific are specific phobias? Journal of Behavior Therapy & Experimental Psychiatry, 28, 233–240.

Hüweler, R., Kandil, F., Alpers, G. W., & Gerlach, A. L. (2009). The impact of visual flow stimuli on anxiety, dizziness, and body sway in persons with and without fear of heights. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 345–352.

Jacob, R. G., Whitney, S. L., Detweiler-Shostak, G., & Furman, J. M. (2001). Vestibular rehabilitation for patients with agoraphobia and vestibular dysfunction: A pilot study. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 15, 131–146.

Johansson, J., & Oest, L. G. (1982). Perception of autonomic reactions and actual heart rate in phobic patients. Journal of Behavioral Assessment, 4, 133–143.

Kamphuis, J. H., & Telch, M. J. (2000). Effects of distraction and guided threat reappraisal on fear reduction during exposure-based treatments for specific fears. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 1163–1181.

Keefer, L., Sanders, K., Sykes, M. A., Blanchard, E. B., Lackner, J. M., & Krasner, S. (2005). Towards a better understanding of anxiety in irritable bowel syndrome: A preliminary look at worry and intolerance of uncertainty. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 19, 163–172.

Kendler, K. S., Myers, J., & Prescott, C. A. (2002). The etiology of phobias: An evaluation of the stress-diathesis model. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 242–248.

Kendler, K. S., Neale, M. C., Kessler, R. C., Heath, A. C., & Eaves, L. J. (1992). The genetic epidemiology of phobias in women. The interrelationship of agoraphobia, social phobia, situational phobia, and simple phobia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49, 273–281.

Kenwright, M., Marks, I. M., Gega, L., & Mataix-Cols, D. (2004). Computer-aided self-help for phobia/panic via internet at home: A pilot study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 184, 448–449.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602.

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 617–627.

Koch, E. I., Spates, C., & Himle, J. A. (2004). Comparison of behavioral and cognitive-behavioral one-session exposure treatments for small animal phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 1483–1504.

Krijn, M., Emmelkamp, P. M. G., Olafsson, R. P., & Biemond, R. (2004). Virtual reality exposure therapy of anxiety disorders: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 259–281.

Kushner, M. G., Krueger, R., Frye, B., & Peterson, J. (2008). Epidemiological perspectives on co-occuring anxiety disorder and substances use disorder. In S. H. Stewart & P. J. Conrod (Eds.), Anxiety and substances use disorders (pp. 3–17). Minneapolis, MN: Springer Science.

Lang, P. J. (1968). Fear reduction and fear behavior: Problems in treating a construct. In J. M. Shlien (Ed.), Research in psychotherapy (Vol. 3, pp. 90–103). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Lange, W. G. T., Tierney, K. J., Reinhardt-Rutland, A. H., & Vivekananda-Schmidt, P. (2004). Viewing behaviour of spider phobics and non-phobics in the presence of threat and safety stimuli. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 235–243.

Lipsitz, J. D., Barlow, D. H., Mannuzza, S., Hofmann, S. G., & Fyer, A. J. (2002). Clinical features of four DSM-IV-specific phobia subtypes. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190, 471–478.

Lipsitz, J. D., Mannuzza, S., Klein, D. F., Ross, D. C., & Fyer, A. J. (1999). Specific phobia 10–16 years after treatment. Depression & Anxiety, 10, 105–111.

Magee, W. J., Eaton, W. W., Wittchen, H. U., McGonagle, K. A., & Kessler, R. C. (1996). Agoraphobia, simple phobia, and social phobia in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53, 159–168.

Marks, I. M. (1969). Fears and phobias. New York: Academic Press.

Marshall, W. L. (1985). The effects of variable exposure in flooding therapy. Behavior Therapy, 16, 117–135.

Mathews, A., & MacLeod, C. (2002). Induced processing biases have causal effects on anxiety. Cognition and Emotion, 16, 331–354.

McNally, R. J. (1987). Preparedness and phobias: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 283–303.

Milosevic, I., & Radomsky, A. S. (2008). Safety behaviour does not necessarily interfere with exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46, 1111–1118.

Mineka, S., Davidson, M., Cook, M., & Keir, R. (1984). Observational conditioning of snake fear in rhesus monkeys. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93, 355–372.

Mineka, S., & Öhman, A. (2002). Phobias and preparedness: The selective, automatic, and encapsulated nature of fear. Biological Psychiatry, 52, 927–937.

Mohlman, J., & Zinbarg, R. (2000). What kind of attention is necessary for fear reduction? An empirical test of the emotional processing model. Behavior Therapy, 31, 113–133.

Morris, R. J., & Magrath, K. H. (1979). Contribution of therapist warmth to the contact desensitization treatment of acrophobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 47, 786–788.

Mowrer, O. H. (1947). On the dual nature of learning – a re-interpretation of “conditioning” and “problem-solving.” Harvard Educational Review, 17, 102–148.

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Holdrinet, I., & Sijsenaar, M. (1998). Treating phobic children: Effects of EMDR versus exposure. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 193–198.

Myers, H. K., MacKinnon, K. J., & Corson, J. A. (1982). Biobehavioral treatment of excessive micturition. Biofeedback & Self Regulation, 7, 467–477.

Öst, L. G. (1989). One-session treatment for specific phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 27, 1–7.

Öst, L. G., Brandberg, M., & Alm, T. (1997). One versus five sessions of exposure in the treatment of flying phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 987–996.

Öst, L.-G., Fellenius, J., & Sterner, U. (1991). Applied tension, exposure in vivo, and tension-only in the treatment of blood phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 29, 561–574.

Öst, L.-G., Lindahl, I.-L., Sterner, U., & Jerremalm, A. (1984). Exposure in vivo vs applied relaxation in the treatment of blood phobia. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 22, 205–216.

Öst, L.-G., & Sterner, U.(1987). Applied tension: A specific behavioral method for treatment of blood phobia. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 25, 25–29.

Öst, L.-G., Stridh, B. M., & Wolf, M.(1998). A clinical study of spider phobia: Prediction of outcome after self-help and therapist-directed treatments. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 17–35.

Park, J. M., Mataix-Cols, D., Marks, I. M., Ngamthipwatthana, T., Marks, M., Araya, R., et al. (2001). Two-year follow-up after a randomised controlled trial of self- and clinician-accompanied exposure for phobia/panic disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry, 178, 543–548.

Poulton, R., & Menzies, R. G. (2002). Non-associative fear acquisition: A review of the evidence from retrospective and longitudinal research. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 127–149.

Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A. J., Otto, M. W., Sanders, C., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2009). Facilitation of fear extinction in phobic participants with a novel cognitive enhancer: A randomized placebo controlled trial of yohimbine augmentation. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 350–356.

Rachman, S. (1977). The conditioning theory of fear-acquisition: A critical examination. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 15, 375–387.

Rachman, S., & Bichard, S. (1988). The overprediction of fear. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 303–312.

Rachman, S., & Levitt, K. (1988). Panic, fear reduction and habituation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 26, 199–206.

Radomsky, A. S., Rachman, S., Thordarson, D. S., McIsaac, H. K., & Teachman, B. A. (2001). The claustrophobia questionnaire. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 15, 287–297.

Rentz, T. O., Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A. J., Cougle, J. R., & Telch, M. J. (2003). Active-imaginal exposure: Examination of a new behavioral treatment for cynophobia (dog phobia). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41, 1337–1353.

Ressler, K. J., Rothbaum, B. O., Tannenbaum, L., Anderson, P., Graap, K., Zimand, E., et al. (2004). Cognitive enhancers as adjuncts to psychotherapy: Use of D-cycloserine in phobic individuals to facilitate extinction of fear. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 1136–1144.

Robichaud, M., & Dugas, M. J. (2006). A cognitive-behavioral treatment targeting intolerance of uncertainty. In G. C. L. Davey & A. Wells (Eds.), Worry and its psychological disorders: Theory, assessment and treatment (pp. 289–304). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishing.

Rodriguez, B. I., & Craske, M. G. (1993). The effects of distraction during exposure to phobic stimuli. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31, 549–558.

Sanderson, W., & Bruce, T. J. (2007). Causes and management of treatment-resistant panic disorder and agoraphobia: A survey of expert therapists. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 14, 26–35.

Sarlo, M., Buodo, G., Munafo, M., Stegagno, L., & Palomba, D. (2008). Cardiovascular dynamics in blood phobia: Evidence for a key role of sympathetic activity in vulnerability to syncope. Psychophysiology, 45, 1038–1045.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1971). Phobias and preparedness. Behavior Therapy, 2, 307–320.

Shafran, R., Booth, R., & Rachman, S. (1993). The reduction of claustrophobia-II: Cognitive analyses. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 31, 75–85.

Shen, Y.-C., Zhang, M.-Y., Huang, Y.-Q., He, Y.-L., Liu, Z.-R., Cheng, H., Tsang, A., et al. (2006). Twelve-month prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in metropolitan China. Psychological Medicine, 36, 257–267.

Sloan, T., & Telch, M. J. (2002). The effects of safety-seeking behavior and guided threat reappraisal on fear reduction during exposure: An experimental investigation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 235–251.

Smits, J. A., Telch, M. J., & Randall, P. K. (2002). An examination of the decline in fear and disgust during exposure-based treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 1243–1253.

Southworth, S., & Kirsch, I. (1988). The role of expectancy in exposure-generated fear reduction in agoraphobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 26, 113–120.

Stern, R., & Marks, I. (1973). Brief and prolonged flooding. A comparison in agoraphobic patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 28, 270–276.

Stinson, F. S., Dawson, D. A., Chou, S. P., Smith, S., Goldstein, R. B., Ruan, W. J., et al. (2007). The epidemiology of DSM-IV specific phobia in the USA: Result from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Psychological Medicine, 37, 1047–1059.

Taylor, J. E., Deane, F. P., & Podd, J. V. (2007). Driving fear and driving skills: Comparison between fearful and control samples using standardised on-road assessment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 805–818.

Thorpe, S. J., & Salkovskis, P. M. (1997). The effect of one-session treatment for spider phobia on attentional bias and beliefs. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36, 225–241.

Vansteenwegen, D., Vervliet, B., Hermans, D., Thewissen, R., & Eelen, P. (2007). Verbal, behavioural and physiological assessment of the generalization of exposure-based fear reduction in a spider-anxious population. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 291–300.

Wolitzky-Taylor, K. B., Horowitz, J. D., Powers, M. B., & Telch, M. J. (2008). Psychological approaches in the treatment of specific phobias: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 1021–1037.

Wolpe, J. (1962). Isolation of a conditioning procedure as the crucial psychotherapeutic factor. Journal of Nerveous and Mental Disease, 134, 316.

Woody, S. R., McLean, C., & Klassen, T. (2005). Disgust as a motivator of avoidance of spiders. Journal of Anxiety Disorder, 19, 461–475.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2010 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Alpers, G.W. (2010). Avoiding Treatment Failures in Specific Phobias. In: Otto, M., Hofmann, S. (eds) Avoiding Treatment Failures in the Anxiety Disorders. Series in Anxiety and Related Disorders. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0612-0_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0612-0_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-1-4419-0611-3

Online ISBN: 978-1-4419-0612-0

eBook Packages: Behavioral ScienceBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)