You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

“The person who can combine frames of reference and draw connections between ostensibly unrelated points of view is likely to be the one who makes the creative breakthrough.”

—Denise Shekerjian

In the previous section, our framework describing the interaction of multiple competing messages provided a useful way to describe how risk communicators should create convergence and understanding with their audiences in pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis situations. In addition, the identification of best practices offers a way to identify why particular risk messages may have more influence than others on how audiences respond. Adding to the complexity of the situation for risk communicators are multiple publics who may not share the same understanding or willingness to respond to the messages due to how the risk or potential crisis may affect them in what we described as spheres of ethnocentricity.

In the complex communication context of risk communication, one research methodology is particularly appropriate, due to its capacity to explore, describe, or explain the dynamics of the situation. The case study approach to research in the social sciences is a fitting method for identifying the interaction between individuals, messages, and context. Yin ) summarizes, “The case study method allows investigators to retain the holistic and meaningful characteristics of real-life events” (p. 2). The case study approach works well to identify best practices for risk communication because individual situations are defined or isolated, relevant data are collected about the situation, and the findings are presented in such a way that a more complete understanding is reached regarding how messages shape perceptions and serve to prompt particular responses from those hearing the messages.

We consider the case study method as both an approach to research and a choice of what to study (Patton, 2002). Therefore, in the construction of the case studies presented in this book, a consistent methodological approach was followed. In order to establish common areas of analysis within the research design, we focused on risk situations involving the unintentional or intentional contamination or compromise of the food system. A conceptual framework based upon the best practices explained in Chapter 2 and a chronological exposition of the pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis messages created consistency as we drew implications about what happened, how it happened, and why. Collectively, the cases allowed us to generalize about the best practices as a whole.

Individually, the choice of cases provided opportunities to demonstrate various aspects of the best practices. Each of the forthcoming cases includes particular situations and context-sensitive information whereby the best practices for risk communication could be identified and studied. In some cases, preemptive communication strategies designed to promote compliant behavior are found. In others, the exposition of the crisis revealed how risks were not anticipated or communicated effectively to the public. In fact, as demonstrated by how a crisis actually unfolded, the evidence suggests that those managing the crisis were not always mindfully considering the competing arguments. Rather than seeking congruence, reliance on economic or social models enabled decision-makers to simplify the risk situation at a time when complexity should have been acknowledged. In such situations, the value of the best practices may not have been recognized until after the crisis had passed.

Justification for the Case Study Approach

We selected the case study approach as a way to illustrate the interactive process involved in the convergence of ris(2003k messages for several reasons. Case studies have been used frequently by scholars and practitioners in public health, agriculture, education, psychology, and the social sciences as a legitimate methodological approach to research (Rogers, 2003; Tuschman & Anderson, 1997). In addition, they provide a method to investigate a contemporary event involving risk within a real life context; and they contribute to enhanced knowledge of complex social phenomena.

Legitimacy as a Methodological Approach

The case study approach has been used to study many different situations involving individual, group, organizational, social, political, and related phenomena (Yin, 2003). Throughout his treatise on diffusion theory, Rogers (2003) offers cases to illustrate the following: social systems (Iowa hybrid corn case), pro-innovation bias (Egyptian villages pure drinking water case), socioeconomic status (California hard tomatoes case), the reinvention process (horse culture among the Plains Indians case), attributions of innovations (photovoltaics, cellular telephones case), adopter types (Old Order Amish case), opinion leadership (Alpha Pups in the viral marketing of an electronics game case), diffusion networks (London Cholera epidemic case), change agents (Baltimore needle-exchange project case), stages in the innovation process (Santa Monica freeway diamond lane experiment case), and the consequences of innovations (steel axes for stone-age Aborigines case), to name but a few.

In their collection of readings on managing strategic innovation and change, Tuschman and Anderson (1997) offer numerous case studies involving technology cycles, design changes, power dynamics in organizations, managing research and development, product development, cross-functional linkages, and leadership styles. Similarly, risk and crisis scholars have used case studies to illustrate best practices and organizational learning.

Sellnow and Littlefield (2005) use case studies describing both accidental and intentional contamination to demonstrate lessons learned about protecting America's food supply. Three cases focused on particular companies and their experiences managing a crisis: Schwan's demonstration of social responsibility in response to a Salmonellacontamination crisis, Chi-Chi's inability to survive a Hepatitis A outbreak despite apologia, and Jack in the Box restaurants' organizational learning following an E. colioutbreak in Seattle, Washington. A case involving interagency coordination and the tainted strawberries in the National School Lunch Program revealed how various stakeholders affect crisis planning efforts. Two cases of potentially intentional contamination—one by Monsanto, a major producer of genetically engineered wheat and the other by the Boghwan Shree Rajneesh cult in an Oregon community—explored the effect of public opinion and outrage.

In their work, Ulmer et al. (2007) provide case studies revealing lessons learned about managing uncertainty, effective communication, and demonstrating leadership. They focused on four areas: industrial disasters (Exxon and the Valdezoil tanker, and the fires at Malden Mills and Cole Hardwoods), food borne illness (Jack in the Box's E. coliO157:H7, Hepatitis A at a Chi-Chi's restaurant, and the Schwan's Salmonellacrisis), terrorism (the case of 9/11, the Oklahoma City bombing, and the CDC's handling of the SARS outbreak), and natural disasters (the 1997 Red River Valley floods, the Tsunami and the Red Cross, and the 2003 San Diego County fires).

Exploring risk and crisis situations in public health, Seeger et al. (2008) categorize case studies focusing on bioterrorism, food borne illness, infectious disease outbreaks, and crisis prevention and responses. Cases of bioterrorism focused on lessons learned from the 2001 Anthrax crisis through the U.S. Postal System; the threat of agro-terrorism in high reliability organizations and organizational responses to the Chi-Chi's Hepatitis A outbreak provided cases demonstrating the risk of food-borne illness and the need for crisis prevention; and the strategies used by communities, nations, and the world when dealing with the risk of West Nile Virus, SARS, Encephalitis, HIV and AIDS provided cases where infectious disease outbreaks required effective risk and crisis responses. These collections and others similarly have found value in studying particular examples of an identified phenomenon for the benefit of understanding more about what, how, and why something happened.

Multiple Sources of Information

One of the reasons supporting the legitimacy of the case study approach is its use of multiple sources of information to establish claims about a particular situation.

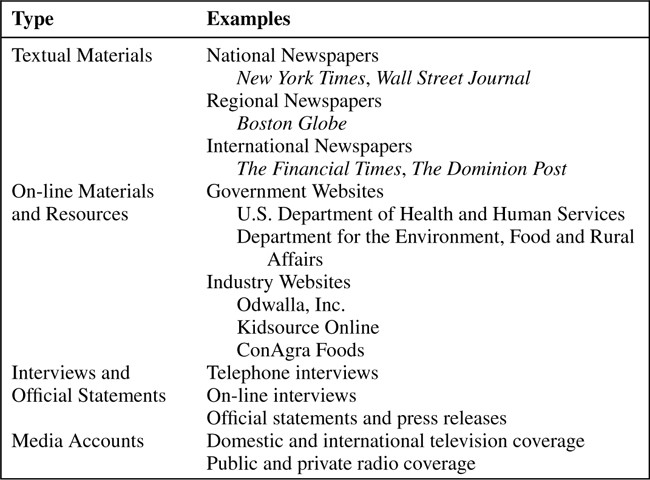

Multiple sources may include textual materials, on-line websites and resources, interviews, media accounts, and personal observations. Due to the nature of the case study approach, choices must be made about the kinds of information to be utilized. Accessibility often dictates the kinds of information to be included, in which case the researchers must continually cross reference to be sure that the most accurate depiction of the situation is conveyed.

For the case studies included within this volume, text-based materials provided the majority of the information consulted (Fig. 4.1). Information drawn from national newspapers (e.g., New York Timesand The Wall Street Journal), regional newspapers (e.g., The BostonGlobe) or—as in the New Zealand foot and mouth hoax case—international outlets (e.g., Financial Timesand The Dominion Post) provided contextual material enabling the researcher to establish the time frame and variables at work in each case. Websites and on-line materials, such as those offered by governmental and industrial groups provided insight from the perspective of those in positions to respond to the risk or crisis situation. A number of groups were accessed through such websites, including the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Department for the Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs, Odwalla, Inc., KidSource Online, and ConAgra Foods. Interviews were conducted with individuals holding positions of responsibility, enhancing the researcher's understanding of the dynamics of the situation in New Zealand.

When interviewing was impossible, official comments from key decision-makers were drawn from the available textual sources. Together, these multiple sources enabled the observer to engage in triangulation, a process where more than one source of information is used when drawing inferences or conclusions about a given situation. Stake (2000) argues that triangulation was valuable not only to clarify meaning, but also to identify “different ways the phenomenon is being seen” (p. 444).

Need for Theoretical Framework

In addition to the need for multiple sources of data to understand the complexity of a risk or crisis situation, another reason researchers use the case study approach stems from the way theoretical propositions may be used to guide data collection and analysis. Case study researchers can set the parameters for what will be included within the analysis. As such, the introduction of a theoretical framework provides an overlay for the data that the researcher may use as a way to explore, describe, or explain what happened. In the selected cases included in this volume, the researchers utilized existing theoretical perspectives about risk and crisis drawn from the professional journals of the field, including Journal of Applied Communication Research, Management Communication Quarterly, Journal of Epidemiol Community Health, and The New England Journal of Medicine. The existing theoretical framework provided a backdrop for considering each case.

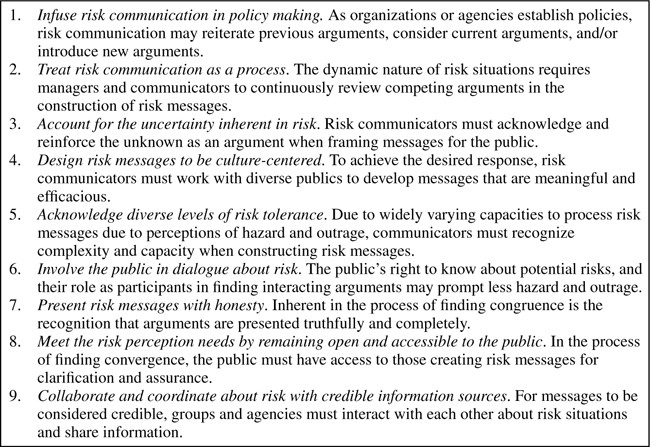

Specifically for this volume, best practices for risk communication were used as a theoretical framework (Fig. 4.2). As already explained in Chapter 2, these best practices are theory driven and stem from the work previously done through a collaboration of risk and crisis communicators who introduced the ten best practices for crisis communication through the National Center for Food Protection and Defense (Seeger, 2006). Each of the case studies used these best practices to help to reveal problems faced by risk and crisis communicators, as well as to identify the strategies used as individuals, organizations, and communities worked to move through the crisis to recovery and in some cases, renewal.

Utility for Investigation into Contemporary Events

In addition to the case study method being multidimensional, researchers value the approach because it provides an empirical way to investigate a contemporary phenomenon within a real life context. There are differences between the case study approach and studies utilizing a more structured research methodology. For example, in an experimental setting, variables may be controlled or accounted for as particular actions are taken to affect the outcome. In this closed environment, researchers can make generalizations based upon the sophistication of their design.

However, situations where risk messages are communicated through the media and events are reported and presented as they unfold, researchers have less control over how competing risk message are transmitted and received by diverse groups within the public. The range of variables that cannot be controlled or manipulated further complicates the coverage of contemporary events outside of the laboratory. For example, Chapter 8 examines the case of in the tainted Odwalla juice, the Cryp-tosporidiumoutbreak case, or in the case of finding Salmonellain ConAgra Foods pot pies, human error could not have been predicted with certainty. In disasters like Hurricane Katrina, elements of nature could not be controlled. They happened. In the New Zealand hoax case, the potential threat of a terrorist's intentional foot and mouth disease could not have been precluded. The realization that a host of variables are interacting in a real-world setting affords the scholar a unique opportunity to explore, describe, and explain events as they occur.

The opportunity to examine what transpired in a particular crisis situation is unique to the case study approach. Due to the dynamic, chaotic nature of crisis events that are not always represented in cause-to-effect relationships, the case study approach enabled us to examine and understand situations in ways that might not have been foreseen prior to the start of our investigation. While not statistically generalizable, after examining several cases, the identification of the presence or absence of the best practices provides researchers with the arguments needed to find consistency about the situation that may have applicability to other similar risk situations. By using the case study framework to separate the pre-crisis from the crisis, observers may note events leading up to the crisis, factors that may have contributed to the way the risks were presented, and what happened (or should have happened) as a result of the way these messages were processed and acted upon.

Enhancement of Knowledge About Complex Phenomena

Within any given situation involving risk, there are many variables of interest, including the processes at work within the dynamic of the situation; the changes that occur due to the introduction of particular risk messages; relations between various stakeholders during the pre-crisis, crisis, or post-crisis situations; and the learning that results following the response to a crisis situation. These variables involving individuals, groups, organizations, or social entities represent the multidimensionality of the phenomena involved in risk communication.

In addition, the varied nature of questions posed by researchers and practitioners pertaining to risk situations further demonstrates how the complexity of a case can be studied using this approach. Case studies seeking to know what happened in a particular context rely on “what” questions. What happened in a particular situation causing a response? When researchers seek answers to “how” questions, they want descriptions. How did an entity communicate risk messages? Researchers seeking explanations regarding the particular motivations of communicators in a situation rely on “why” questions. Why were company spokespeople compelled to communicate particular messages to the public about a risk situation? In contrast to quantitative and qualitative methodologies where researchers tend to focus on one dimension or variable, the case study approach enables the researcher to use all of these questions. Questions like these are used throughout the cases to reveal the multidimensionality of the risk and crisis events.

Establishing a Framework for Case Studies

Identifying a framework for case studies is essential if comparisons are to be made. Stake (2000) suggests the following items as essential in the creation of a case study:

The nature of the case; the case's historical background; the physical setting; other contexts (e.g., economic, political, legal, and aesthetic); other cases through which this case is recognized; and those informants through whom the case can be known. (pp. 438– 439)

Thus, to provide clarity, we determined that each case study should be written to include common elements providing comparable information for the reader to consider. In the following case studies, we provide:

-

An introduction and overview of the case.

-

Evidence and application of the best practices for risk communication within the case.

-

Lessons learned and implications drawn from the use of best practices for risk communication.

From a research perspective, with these elements as constants, individual authors were able to gather data appropriate to each case and uniformly present their findings. In addition, similar textual materials were used in each of the studies, providing the reader with comparable information to consider.

Five Cases of Risk Communication

Stake (2000) argues that, “perhaps the most unique aspect of the case study is the selection of cases to study” (p. 446). With this in mind, we selected crisis situations where the presence or absence of best practices for risk communication could be identified, providing the readers with insight into how risk communication may or could have been used to affect the behavior of various stakeholders prior to the onset of a crisis situation. Each case study is unique in the risks posed, as well as how the communication agent sought to affect compliant behavior from the various stakeholders receiving the risk messages.

In the case of the Cryptosporidiumcrisis, the risks associated with water quality in a major metropolitan area and a community's response to a water quality crisis are examined. The risks associated with inadequate planning and the events related to the Hurricane Katrina disaster reveal how different levels of the government responded to a natural disaster. A government's use of interacting arguments revealed a paradox between appearing to accept the risk of foot and mouth disease and dismissing its likelihood on a New Zealand island. The Odwalla case study focuses on the risks associated with their trademark apple juice and how it struggled to renew itself within the health food industry. Finally, the ConAgra Foods Salmonellacase study features the complexities of addressing multiple audiences during a major recall event involving pot pies.

“Cryptosporidium: Unanticipated Risk Factors,” provides the example of a community organization that experienced a crisis because it did not respond in time to government warnings calling for stronger guidelines for guarding municipal water against Cryptosporidiuminvasions. At the time of the crisis, Milwaukee had no water monitoring systems in place and the outbreak served as a wake-up call by exposing weaknesses in the public health system and pointing out the bioterrorism risks. Throughout the crisis, community leaders failed to be open, honest, and timely with the information they provided to the public. They failed to be mindful of public concerns expressed prior to the cryptosporidium outbreak. In addition, they did not collaborate or coordinate across agencies, exacerbating the crisis. Milwaukee was unprepared but learned from the event, established a plan should such a crisis occur in the future, and now has one of the safest water treatment systems in the country.

“Hurricane Katrina: Risk Communication in Response to a Natural Disaster,” examines how local leaders failed to create an adequate crisis plan, despite having knowledge of the damage that would occur if a hurricane of Katrina's magnitude struck New Orleans. While local crisis managers had a plan, its usefulness was mitigated by the length and format of the document. Once the hurricane struck, New Orleans crisis managers faced the difficult challenge of collaborating and coordinating resource distribution to affected residents. Another difficulty was getting information to the stakeholders. In the pre-crisis and crisis stages, the media were often ahead of local officials in presenting information to residents. This compromised the local officials' credibility and accountability. Clearly, lack of pre-event planning, the absence of collaboration and coordination, and the need for honest, candid, open, and accountable communication are key reasons why local crisis managers were unable to plan for, manage, and move past what was a devastating event for New Orleans and the surrounding region.

“New Zealand Beef Industry: Risk Communication in Response to a Terrorist Hoax” expands knowledge of risk communication by introducing how hoaxes and terrorist threats complicate our understanding of risk situations. In New Zealand, after receiving a threat claiming a deliberate release of the foot and mouth disease virus on Waiheke Island, the government had to provide intersecting messages demonstrating their capacity to manage the crisis situation. In essence, they claimed to be treating the situation as a potential crisis, while at the same time indicating their belief that the threat was a hoax. Managing crisis uncertainty became the focus for local leaders as they presented messages minimizing the risk as a hoax while acknowledging their treatment of the message as a viable threat to the security of the cattle and the New Zealand economy. The pre-crisis partnerships established between crisis managers and the various stakeholders proved valuable as the agencies worked together to disseminate information and communicate with the local citizens, as well as New Zealand's international partners. While a crisis plan was in place, and had been tested, there were some initial concerns raised by the local public that were ultimately mitigated due to open communication, as well as an attitude of compassion and empathy demonstrated by crisis spokespeople. While the hoax never developed into a crisis, providing messages of self-efficacy about checking for symptoms became an effective way to garner public confidence.

How a company managed to survive the challenge of an E. colioutbreak associated with one of its juice products is the subject of the chapter, “Odwalla: The Long Term Implications of Risk Communication.” Despite the potential risks associated with the continued consumption product, the public stood by Odwalla and its actions during and after the crisis. Odwalla met the needs of the media and remained accessible by holding press conferences, continually updating a website, instituting a hotline, and maintaining open communication with consumers and the press. The company delivered messages of self-efficacy and offered multiple ways for consumers to remain safe. In addition, company leaders apologized publicly, acknowledged the tragedy of the situation, paid medical bills for victims, and acknowledged the impact of the crisis on the image of the company. Following the crisis, Odwalla created an advisory council that ultimately recommended a new pasteurization process, breaking new ground in the industry. The use of some of the best practices enabled Odwalla to embrace a crisis, use it as an opportunity to become an industry leader, initiate industry wide change, and to encourage organizational renewal.

“ConAgra: Audience Complexity in Risk Communication” focuses on the need for organizations to consider multiple audiences when issuing risk messages. In the process of what appeared to be a demonstration of more concerned about their bottom line than with the safety of their customers, ConAgra initially shifted the blame for the outbreak to consumers for not cooking the pot pies properly. In addition, ConAgra made overly-assuring statements to the public about which products were affected by Salmonella(chicken and turkey), and which were not (beef). The assumptions made by ConAgra Foods about the literacy levels, economic status, access to media, proximity to outbreak, and cultural group identities of those receiving the risk messages also complicated their communication with stakeholders. In this case, once Salmonellawas linked to ConAgra Foods' pot pies, the company issued a recall of all brands associated with their product. While additional information about the ConAgra Foods recall has yet to emerge, the case points to the need for greater attention by company spokespeople to the best practices of risk communication in order to preserve a positive reputation with the public.

Summary

This chapter introduced the case study method as a viable way to study risk communication in crisis situations. Our reasons for choosing the case study approach include its utility for exploring situations from multiple points of view, its usefulness when investigating contemporary events, and its ability to provide enhanced knowledge about complex phenomena. The best practices of risk communication, based on the best practices of crisis communication (Seeger, 2006), provide the theoretical framework for the case studies included in this book.

The framework we used for the case studies includes an introduction and overview to the case, a timeline of events, evidence and application of the best practices, and lessons learned. Five cases were introduced: the Milwaukee Cryp-tosporidiumcrisis, the Hurricane Katrina crisis, the New Zealand foot and mouth disease hoax crisis, the Odwalla juice crisis, and the ConAgra Foods Salmonellacrisis. In each case, the best practices of risk communication provide insight into what occurred, or failed to occur, and the implications that followed in each crisis situation.

The five case studies provide insight into the best practices of risk communication. In all of the cases, risk communicators should have acknowledged competing arguments in the construction of risk messages. For example, the Cryptosporid-iumcase demonstrates the need to infuse risk communication into policy making. By accepting that current practices would take care of the problem, local leaders allowed the crisis to develop. In the Hurricane Katrina case, the dynamic state of affairs required communicators to continuously review the situation and be proactive in communicating strategies of self-efficacy. Regarding the New Zealand potential foot and mouth disease case, a clear argument exists for why risk communicators must acknowledge and reinforce the unknown when framing messages for the public. Similarly, the collaboration and coordination among agencies with credible information sources helped the New Zealand crisis leaders build support among the various stakeholders affected by the potential contamination. As for Odwalla, the company was forced to acknowledge diverse levels of risk tolerance as the complexity of the situation unfolded. Similarly, a recognition of the need for a culture-centered approach would have enhanced the communication of ConAgra Foods with consumers and demonstrated a commitment to safety over profit. The following five chapters serve as examples of case studies involving risk communication.

References

Patton, M. Q. (2002).Qualitative research and evaluationmethods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rogers, E. M. (2003).Diffusion of innovations(5th ed.). New York, NY: Free Press.

Seeger, M. W. (2006). Best practices in crisis communication: An expert panel process.Journal of Applied Communication Research 34(3), 232–244.

Seeger, M. W., Sellnow, T. L., & Ulmer, R. R. (Eds.). (2008).Crisis communication and the public health. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press, Inc.

Sellnow, T. L., & Littlefield, R. S. (Eds.). (2005).Lessons learned about protecting America's food supply: Case studies in crisis communication. Fargo, ND: Institute for Regional Studies.

Stake, R. E. (2000). Case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.)Handbook of qualitative research(2nd ed.), (pp. 435–454). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tuschman, M. L., & Anderson, P. (1997).Managing strategic innovation and change: A collection of readings. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ulmer, R. R., Sellnow, T. L., & Seeger, M. W. (2007).Effective crisis communication: Moving from crisis to opportunity. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2003).Case study research: Design and methods(3rd ed.). Applied Social Research Methods Series, Vol. 5. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2009 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

(2009). The Case Study Approach. In: Effective Risk Communication. Food Microbiology and Food Safety. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79727-4_4

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-79727-4_4

Publisher Name: Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN: 978-0-387-79726-7

Online ISBN: 978-0-387-79727-4

eBook Packages: Chemistry and Materials ScienceChemistry and Material Science (R0)