Abstract

This paper discusses the problems of analyzing title page layouts and extracting bibliographic information from academic papers. Information extraction is an important function for digital libraries to offer, providing versatile and effective access paths to library content. Sequence analyzers, such as those based on a conditional random field, are often used to extract information from object pages. Recently, digital libraries have grown and can now handle a large number and wide variety of papers. Because of the variety of page layouts, it is necessary to prepare multiple analyzers, one for each type of layout, to achieve high extraction accuracy. This makes rule management important. For example, at what stage should we invest in a new analyzer, and how can we acquire it efficiently, when receiving papers with a new layout? This paper focuses on the detection of layout changes and how we learn to use a new sequence analyzer efficiently. We evaluate the confidence metrics for sequence analyzers to judge whether they would be suited to title page analysis by testing three academic journals. The results show that they are effective for measuring suitability. We also examine the sampling of training data when learning how to use a new analyzer.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

The digitization of documents has infiltrated our society and one piece of evidence is the rapid spread of electronic book reading devices such as iPad and Kindle. What we really need in such circumstances is not just the digitization of books, but digitization of all the printed or written documents in our society, which would create an information archive accessible from all over the world. Needless to say, digital libraries (DLs) would be one such type of information archive. Recently, some universities and research institutions have set up web-accessible archives as their own institutional repositories. Although metadata such as bibliographic information about documents are indispensable for the efficient access to and utilization of digital documents, techniques for creating digital documents with appropriate metadata are not yet mature enough to be used in real applications. Extracting information that includes bibliographic data from documents is a key technology for realizing such information archives as intellectual legacies because it will enable the extraction of various kinds of metadata and will provide the users of such archives with full access to rich information sources.

For documents such as the academic papers studied here, the important bibliographic information will include the title, author information, and journal name. Extracting such bibliographic information from an academic paper is useful in creating or reconstructing metadata. For example, it could be used to link identical records stored in different DLs and for faceted retrieval. Although many researchers have studied bibliographic information extraction from papers and documents [2, 12, 15], it remains an active research area, with several competitions having been heldFootnote 1.

For accurate information extraction, researchers have developed various rule-based methods that can exploit both logical structure and page layout. However, document archives such as DLs usually handle several different types of document. Because formulating and managing them requires effective and efficient methods, the rules used should be tailored to suit each type of document. Rule management becomes harder as the system grows and contains more papers with more varieties of types of layout. For example, when receiving a fresh set of documents, we must determine whether we should generate a new set of rules or use the existing rules. In addition, the rules should be properly updated because the layout of a particular type of document may sometimes change over time. To maintain such document archives, we require a rule management facility that can measure the suitability of rules and recompile sets of rules when required.

As reported previously, we have been developing a DL system for academic papers [9, 10, 15]. We are especially interested in extracting bibliographic information such as authors and titles. In previous studies, we applied a conditional random field (CRF) [5] to extract bibliographic information from the title pages of academic papers. In these studies, we observed that rule-based methods, whereby a CRF exploits several rules as a form of feature vector, can extract metadata with high accuracy. However, we had to use multiple CRFs, choosing the one to use according to the page layout of the target journal. In other words, we had to access sufficient homogeneously laid-out pages to be able to identify a CRF that could analyze the pages with high accuracy for this metadata extraction task.

The use of multiple CRFs for metadata extraction from documents requires rule management functions such as choosing the appropriate CRF for a particular document or deciding when to make a new CRF to handle a new or changed page layout. This led us to study management rules for page layout analysis and bibliographic information extraction from title pages [16].

In this paper, we first examine the effectiveness of multiple CRFs for information extraction from pages with various page layouts. We compare the labeling performance of a single CRF and multiple CRFs in active learning and show that multiple CRFs perform better when analyzing the title pages of multiple journals. We then propose a method that uses confidence metrics calculated for the CRFs to measure the suitability of each CRF to a particular page layout among the layouts used for training. Our experimental results show that the metric’s value decreases significantly when the CRF is applied to the title page of a journal that is different from the one used for learning the CRF.

This result indicates that the confidence metrics are effective in detecting page layout changes. We also examine the effectiveness of the metrics in selecting training samples during active sampling when learning a CRF for a new page layout.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 defines the problem addressed by this study. Section 3 proposes a rule management method for title page analysis. Our experimental results are given in Sect. 4.

2 Problem Definition

Information extraction from academic papers has been studied by the document image analysis community [6, 14]. In early work, researchers aimed to extract information from scanned document images. To realize highly accurate extraction, they have recently developed extraction methods specific to document components such as mathematical expressions [18], figures [1], and tables [17]. This paper deals with the extraction of bibliographic information such as titles, authors, and abstracts [12], which is one of the fundamental extraction tasks. Although bibliographic information may appear in various parts of the document, including title pages and reference sections, this paper focuses on title page analysis.

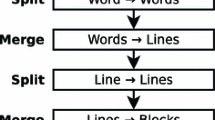

To extract bibliographic components such as the title and authors from title pages, we first extract tokens and apply a sequence analyzer to label each token with its type of bibliographic component. A character, word, or line can be regarded as a token. We choose lines as tokens because they achieved higher extraction accuracy in our preliminary experiments. Figure 1 shows an example of a title page. The red rectangles are tokens extracted from the portable-document-format (PDF) file of the paper. In the figure, note that some bibliographic components are separated into tokens, such as the abstract. In addition, lines themselves can be split into multiple tokens, such as the title of the paper. The sequence analyzer merges the tokens comprising a single bibliographic component by labeling them as the same component. As a result, we obtain a set of bibliographic components, each of which comprises one or more tokens, as shown in Fig. 1.

Because bibliographic components are located in a two-dimensional (2D) space, some researchers have proposed rules that can analyze components of a page based on a page grammar [3] or a 2D CRF [7, 19]. Others have proposed applying sequential analysis after serializing components of the page in a preceding step. For example, Peng et al. [12] proposed a CRF-based method for extracting bibliographic components from the title pages and reference sections of academic papers in PDF format. Councill et al. [2] developed a CRF-based toolkit for page analysis and information extraction. We adopt their approach and use a linear-chain CRF [5] as a sequence analyzer.

If the layout of the title page is different from that used when learning the CRF, the accuracy of extraction of the bibliographic components can be degraded. For large DLs, which will usually contain a variety of journals, the system will need to prepare multiple CRFs and choose one suitable for the target title page. The DL system will sometimes receive title pages for a new journal or for one with a redesigned layout. For these changes of layout, the system may not be able to analyze the title pages accurately. To address these difficulties, this paper considers the following problems:

-

measuring the suitability of a CRF for a type of title page,

-

detecting title pages that cannot be analyzed accurately with existing CRFs, and

-

learning a new CRF so as to analyze pages efficiently for a new layout.

3 Layout Change Detection and CRF Learning

3.1 System Overview

We are developing a DL system to handle the variety of journals published in Japan. Because their bibliographic information is stored in multiple databases, the system creates linkages by locating identical papers in the multiple databases. It also provides a testbed for scholarly information studies such as citation analysis and paper recommendation.

The system aims to handle both newly published papers and papers published previously but not yet included in the system. As stated in the previous section, we use multiple CRFs in extracting information from the variety of journals. The system chooses a CRF according to the journal title and then applies it to that journal’s papers to extract bibliographic information.

Whenever the layout of a paper changes or a new journal is incorporated, we must judge whether we can use a CRF already in the system or should build a new CRF. The system supports rule maintenance by:

-

checking the suitability of a CRF for a given set of papers and alerting the user if the CRF does not analyze them with high confidence, and

-

supporting the labeling of training data when a new CRF is generated.

3.2 The CRF

As described above, we have adopted a linear-chain CRF for the extraction of bibliographic information from the title pages of academic papers. Let L denote a set of labels. For a token sequence \(\varvec{x} := x_1x_2\cdots x_n\), a linear-chain CRF derives a sequence \(\varvec{y}:= y_1y_2\cdots y_n\) of labels, i.e., \(\varvec{y} \in L^n\). A CRF M defines a conditional probability by:

where \(Z(\varvec{x})\) is the partition constant. The feature function \(f_k(y_{i-1},y_i, \varvec{x})\) is defined over consecutive labels \(y_{i-1}\) and \(y_i\) and the input sequence \(\varvec{x}\). Each feature function is associated with a parameter \(\lambda _k\) that gives the weight of the feature.

In the learning phase, the parameter \(\lambda _k\) is estimated from labeled token sequences. In the prediction phase, the CRF assigns the label sequence \(\varvec{y}^*\) to the given token sequence \(\varvec{x}\) that maximizes the conditional probability in Eq. (1).

3.3 Change Detection

To detect a layout change in a token sequence, we use metrics that give the likelihood that the token sequence was generated from the model. This problem is similar to the sampling problem in active sampling [13].

In Eq. (1), the CRF calculates the likelihood based on the transition weight from \(y_{i-1}\) to \(y_i\) and the correlation between a feature vector \(x_i\) and a hidden label \(y_i\). A change of page layout may affect the transition weight between hidden labels in addition to the layout features in \(x_i\). This will lead to a decrease in the likelihood \(P(y^* \mid x, M)\) of the optimal label sequence \(y^*\) given by Eq. (1). A natural way to measure the model suitability is to use this likelihood. The CRF calculates the hidden label sequence \(\varvec{y}^*\) that maximizes the conditional probability given by Eq. (1). A higher \(P(\varvec{y}^*\mid \varvec{x},M)\) means a more confident assignment of labels, whereas a lower \(P(\varvec{y}^*\mid \varvec{x},M)\) means that the token sequence will make it hard for the current CRF model to assign labels.

The conditional probability is affected by the length of the token sequence \(\varvec{x}\). We therefore use the normalized conditional probability for the model suitability measure, as follows:

Here, \(|\varvec{x}|\) denotes the length of the token sequence \(\varvec{x}\). We refer to the metric given by Eq. (2) as the normalized likelihood. The normalized likelihood is a type of confidence measure for when the model assigns labels to all tokens in the sequence \(\varvec{x}\).

A second measure is based on the confidence in assigning labels to a single token in the sequence. For a sequence \(\varvec{x}\), let \(Y_i\) denote a random variable for assigning a label to the ith token in \(\varvec{x}\). For label l in a set L of labels, \(P(Y_i = l)\) denotes the marginal probability that label l is assigned to the ith token. If the token has feature values clearly supporting a specific label \(l \in L\), \(P(Y_i = l)\) must be significantly high and \(P(Y_i = l') \ (l' \ne l)\) must be low. The following entropy value can therefore quantify a token-level confidence:

A low entropy value signifies that the label of token \(x_i\) is likely to be l. For the sequence analysis, an analyzer is regarded as succeeding in its analysis only if it assigns the correct label to every token. In other words, its confidence should be measured by the most difficult token to label. According to this perspective, we can use the maximum entropy of a token sequence \(\varvec{x}\) as another model of confidence, as follows:

As opposed to the normalized likelihood, the maximum entropy can be regarded as a worst-case token-level metric.

The third metric is similar to the maximum entropy, but it measures the token-level confidence in terms of the maximum probability of label assignment to the token. It measures the confidence in the CRF for a token sequence \(\varvec{x}\) as the minimum of the token-level maximum probabilities over the sequence. It is defined formally as follows:

It is referred to as the min-max label probability.

Suppose that CRF M is used to label a token sequence obtained from a title page. There is more than one way to define the change detection problem, but the most basic definition is as follows. Given a new token sequence \(\varvec{x}\), determine whether the sequence is from the same information source as that from which the current CRF M was learned.

A token sequence \(\varvec{x}\) is judged to be a token sequence from the same information source if \(C(\varvec{x}) > \sigma \) holds for a predefined threshold \(\sigma \), where C is \(C_l\) \(C_e\), or \(C_m\). Otherwise, the layout is regarded as having changed.

Because an issue of a journal will usually contain multiple papers, the change detection problem can be solved by detecting a change of title page layout adopted in journals when given a set of token sequences.

3.4 Learning a CRF for a New Layout

If we detect papers with a page layout that is different from those already known, we must derive a new CRF for these papers. We apply an active sampling technique [13], as follows:

-

1.

Gather a significant number of papers T without labeling.

-

2.

Choose an initial small number of papers \(T_0\) from T, label them, and learn an initial CRF \(M_0\) using the labeled papers.

-

3.

At the tth iteration:

-

(a)

Let \(\bar{T}\) be \(T - \cup _{i=0}^{t-1} T_i\).

-

(b)

Calculate a metric described in Sect. 3.3 for each page in \(\bar{T}\) using the CRF \(M_{t-1}\) obtained in the previous iteration.

-

(c)

Choose the bottom-k papers \(T_t\) from \(\bar{T}\) according to the metric.

-

(d)

Label the papers \(T_t\) manually.

-

(e)

Learn CRF \(M_t\) using the labeled papers \(\cup _{i=0}^t T_i\).

-

(a)

The aim of active sampling is to reduce the cost of labeling required to learn the CRF. Note that we need to delay learning a new CRF until we have gathered enough papers in the new layout (Step 1).

In active sampling, the sampling strategy for the initial CRF (Step 2) and for updating the CRF (Step 3(c)) is important. For the initial CRF, we choose k papers in T with the lowest values for the metric C introduced in Sect. 3.3, where C is calculated using the CRFs that we have at that time. This strategy means that we choose training papers \(T_0\) that differ most in layout from those that we have so far.

In the tth update phase, we choose k training papers from \(T - \cup _{i=0}^{t-1} T_i\) with the lowest values for the metric C, where C is calculated using the CRF \(M_{t-1}\) that we obtained in the previous step. This strategy means that we choose training papers with a different layout from those in \(\cup _{i=0}^{t-1} T_i\).

4 Experimental Results

This section examines empirically the metrics for model fitness described in Sect. 3 by evaluating their effectiveness in detecting layout changes and in selecting training samples incrementally in active sampling.

4.1 Dataset

For this experiment, we used the same three journals as in our previous study [8], as follows:

-

Journal of Information Processing by the Information Processing Society of Japan (IPSJ): We used papers published in 2003 in this experiment. This dataset contains 479 papers, most of them written in Japanese.

-

English IEICE Transactions by the Institute of Electronics, Information and Communication Engineers in Japan (IEICE-E): We used papers published in 2003. This dataset contains 473 papers, all written in English.

-

Japanese IEICE Transactions by the Institute of Electronics, Information and Communication Engineers in Japan (IEICE-J): We used papers published between 2000 and 2005. This dataset contains 964 papers, most of them written in Japanese.

As in [8], we used the following labels for the bibliographic components:

-

Title: We used separate labels for Japanese and English titles because Japanese papers contained titles in both languages.

-

Authors: We used separate labels for author names in Japanese and English as in the title.

-

Abstract: As with the title and authors, we used separate labels for Japanese and English abstracts.

-

Keywords: Only Japanese keywords are marked up in the IEICE-J.

-

Other: Title pages usually contain paragraphs such as introductory paragraphs that are not classified into any of the above bibliographic components. We assigned the label “other” to the tokens in these paragraphs.

Note that different journals have different bibliographic components in their title pages.

Because we used the chain-model CRF, the tokens must be serialized. We therefore used lines extracted via OCR as tokens and serialized them according to the order generated by the OCR system. We labeled each token for training and evaluation manually.

4.2 Features of the CRF

As in [8], 15 feature templates were adopted. Of these, 14 were unigram features, i.e., the feature function \(f_k(y_{i-1}, y_i, \varvec{x})\) in Eq. (1) is calculated independently of the label \(y_{i-1}\). There was one remaining bigram feature, i.e., the feature function \(f_k(y_{i-1}, y_i, \varvec{x})\) is calculated independently of the token sequence \(\varvec{x}\). The unigram feature templates were further categorized into two kinds of features. Some involved layout features such as location, size, and gaps between lines. Others involved linguistic features such as the proportions of several kinds of characters in the tokens and the appearance of characteristic keywords that often appear in a particular bibliographic component such as “Institute” in affiliations. Table 1 summarizes the set of feature templates. Their values were calculated automatically from the token and label sequences.

An example of the bigram feature template \(<y(-1),y(0)>\) is:

This bigram feature indicates whether an author name follows a title in a label sequence, with the corresponding parameter \(\lambda _k\) showing how likely it is that an author name follows a title. CRF++ 0.58Footnote 2 [4] was used to learn and to label the token sequence for the title pages of each journal.

4.3 Bibliographic Component Labeling Accuracy

We first examined the bibliographic component labeling accuracy of CRFs. The purpose of this experiment was to evaluate the effectiveness of:

-

the metrics described in Sect. 3.3 for active sampling, and

-

multiple CRFs, each of which was learned for a particular layout of title pages.

We applied fivefold cross-validation. For each of the IPSJ, IEICE-E, and IEICE-J journals, we randomly split manually labeled title pages into five equal-sized groups of pages. In each round of the cross-validation, we examined the active sampling described in Sect. 3.4, choosing 10 papers randomly as the initial training data and the 10 least-confidently labeled papers according to the normalized likelihood at each iteration of the active sampling process.

We measured the accuracy of a learned CRF using the test token sequences for the same journal as the training data in each round of the cross-validation. The accuracy was measured by:

Note that a CRF was only regarded as having succeeded in labeling if it assigned correct labels to all tokens in the token sequence. In other words, if a CRF assigned an incorrect label to one token despite correctly labeling all other tokens in a sequence \(\varvec{x}\), it was regarded as having failed.

Figures 2 (a), (b), and (c) show the accuracy of CRFs for the IPSJ, IEICE-E, and IEICE-J journals, respectively. Each graph in the figure plots the accuracy of the CRF with respect to the size of training samples obtained at each iteration of the active sampling process. We first plotted the results of normalized likelihood, shown as a green curve in Fig. 2 and labeled as nlh. As shown in the graph, the accuracy increases as the active sampling proceeds. It converges when the training data size reaches about 50 for IPSJ and IEICE-E, whereas IEICE-J required about 250 training pages.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the metric for active sampling, we measured the accuracy of CRFs obtained for various quantities of randomly chosen training data. The purple curves labeled as random show the average accuracy of the random sampling with respect to the size of the set of training data. As shown in Fig. 2, we need much more training data to achieve an accuracy competitive with active sampling. In fact, we needed about 250 training pages for IPSJ and IEICE-E and more than 500 training pages for IEICE-J. In summary, using active sampling with the normalized likelihood described in Sect. 3.3 significantly reduces the training data required for learning CRFs to be used in bibliographic component labeling.

To evaluate the effectiveness of learning a separate CRF for each journal, we measured the accuracy of CRFs that were learned from merged training data for the three journals. More precisely, we merged the training data of the three journals to form the T used for the active sampling described in Sect. 3.4. We call the resultant CRF a general-purpose CRF. As in the evaluation of active sampling, we chose 10 initial training pages and the 10 least-confidently labeled pages from the merged training data and measured the accuracy of the learned CRFs with respect to the test data for each journal separately. This experiment corresponds to the case of a single CRF being used to analyze the title pages of three journals.

The blue curves labeled as all-nlh in Fig. 2 show the average accuracy of the general-purpose CRFs when they were tested with the papers of the journals IPSJ in Fig. 2 (a), IEICE-E in Fig. 2 (b), and IEICE-J in Fig. 2 (c), respectively. Note that the convergence of the general-purpose CRFs differs according to the test journal used. For example, the accuracy converges at about 400 training papers for IPSJ papers, whereas more than 450 training papers were required for IEICE-J and IEICE-E papers. By comparing nlh and all-nlh, we can see that the separate CRFs converge for a smaller training dataset than that for a general-purpose CRF. In a fairer comparison, the separate CRFs require 50, 50, and 250 training papers for IPSJ, IEICE-E, and IEICE-J journals, respectively. This means that we would require 350 training papers in all to learn the separate CRFs, whereas we required more than 500 training papers for the general-purpose CRF.

The separate CRFs are more accurate than the general-purpose CRF. At convergence, the increased accuracy for the separate CRFs, as compared to the general-purpose CRF, are 2.2 % for IPSJ, 8.9 % for IEICE-E, and 2.6 % for IEICE-J. We also learned CRFs using randomly chosen papers from the merged training data. The red curves labeled as all-random show the average accuracy with respect to the training dataset size. We observed that using active sampling is effective, as with the separate CRFs, except for the IEICE-E case. Even in this exceptional case, active sampling achieved better accuracy for larger training datasets. In general, the metric described in Sect. 3.3 is effective in enabling active sampling to learn CRFs for bibliographic component labeling.

4.4 Change Detection Performance

This section evaluates the sensitivity of the confidence metrics with respect to layout change. For this purpose, we first learned a CRF by using training data for each journal. In the test phase, we merged the test sets for two journals including the training set and let the CRF judge if each title page in the merged test sets came from the training journal. If the title page was judged to come from the training journal, we regarded the page as positive. Otherwise it was regarded as negative.

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was used for evaluation. That is, the merged sets of test title pages were ranked according to the metric described in Sect. 3.3. By regarding the top k pages in the list as positive, we calculated the true-positive and false-positive fractions for each k. For each false-positive fraction, we plotted the averaged true-positive fractions over the five trials in the cross-validation as the ROC curve.

Figure 3 shows the ROC curves for each pair of journals. Each panel contains the ROC curves for the normalized likelihood labeled as nlh, for the maximum entropy labeled as me, and for the min-max label probability labeled as mp. For example, the ROC curves in Fig. 3 (a) are the results of detecting title pages of IEICE-E from those of IPSJ using the CRF learned by labeled IPSJ training sequences. Similarly, the ROC curves in panel (b) are the results of detecting title pages of IEICE-J from those of IEICE-E using the CRF learned from labeled IEICE-E training data.

Two conclusions can be drawn from these results. First, the ROC curves show that the three metrics are very effective for detecting a test page different from the journal used for learning. Among the three metrics, the normalized likelihood is most effective for this detection. Note that both the maximum entropy and the min-max label probability can estimate the worst-case token-level confidence. This result indicates that focusing on the least-confident token in the sequence is not a good strategy for layout-change detection. We did not observe a significant difference between the maximum entropy and the min-max label probability. The latter was effective for detecting IEICE-E from IPSJ, as shown in Fig. 3 (a), whereas the former was effective for detecting IPSJ from IEICE-J, as shown in Fig. 3 (f).

Second, the journal used for learning affects the ability to detect changes. For example, compare panels (d) and (f) in Fig. 3. In both panels, we could discriminate IPSJ and IEICE-J. However, IPSJ was used for training in panel (d), whereas IEICE-J was used for training in panel (f). The panels show that the CRF learned by IEICE-J is better than the CRF learned by IPSJ.

4.5 CRF Learning Using Additional Training Data

In Sect. 4.3, we evaluated the effectiveness of the active sampling when applied to each journal independently. When learning a new CRF for pages whose layout is different from those in the system, we can utilize the labeled training data for journals already stored in the system. It may further reduce the cost of preparing the training data, as in the case of transfer learning [11]. To examine the effect of labeled data associated with other journals, we modified the active sampling procedure described in Sect. 4.3. That is, we added 100 randomly chosen pages from the labeled training title pages of another journal to the 10 initial training title pages. The accuracy of the CRF was measured using Eq. (7).

Figure 4 shows the accuracy of the CRFs for journals IPSJ, IEICE-E, and IEICE-J. Each graph in the figure plots the accuracy of the CRF with respect to the size of the training sample dataset chosen according to the normalized likelihood and the min-max label probability. For example, panel (a) shows the accuracy of the CRF learned from title pages of IPSJ with 100 additional title pages from IEICE-E.

The red curve labeled as tr-nlh depicts the accuracy for the case of training samples being chosen according to the normalized likelihood. The blue curve labeled as tr-mp depicts the accuracy for the case of training samples being chosen according to the min-max label probability. For comparison, the green curve labeled as nlh depicts the accuracy of the CRF that was learned without additional training data and sampled according to the normalized likelihood. Note that the green curves are the same as nlh in Fig. 2.

We observe that the normalized likelihood and the min-max label probability have similar performance with respect to the training dataset size, for all the cases in the experiment. One remarkable point is that the min-max label probability performed better than the normalized likelihood at the initial step, where 10 training datasets and 100 additional training datasets were used for training.

By comparing the curves nlh and tr-mp, we observe that tr-mp tends to perform better than nlh for a training dataset size of 10. For larger training datasets, tr-mp performs as well as nlh for IPSJ and IEICE-E, whereas it performs less well than nlh for IEICE-J. This result indicates that using additional training datasets from different journals is effective for the initial CRF learning, but it may become less effective as more training datasets for the target journal is used. This could be improved by introducing a weighting to the pages of the target and other journals according to the training dataset size.

5 Conclusions

We examined three confidence measures derived from a linear-chain CRF for detecting layout changes in the title pages of academic papers. We applied the measures to the active sampling process used in learning CRFs. Our experiments revealed that the confidence measures are very effective in detecting layout changes and that the measures can be used for active sampling, which will reduce the labeling cost for the training data.

We plan to extend this study in several directions. First, we will study methods that might make the best use of the data accumulated in the system so far. In our experiments, we observed that additional training data is effective when obtaining an initial CRF in the active sampling process. We will look for effective ways to utilize additional training data, as occurs in transfer learning. Second, we will study methods for making clusters of title pages for learning separate CRFs. In this paper, we split the data according to the journal type, when learning the separate CRFs. In future work, we will seek optimal ways of splitting the data for learning separate CRFs.

References

Choudhury, S.R., Mitra, P., Kirk, A., Szep, S., Pellegrino, D., Jones, S., Giles, C.L.: Figure metadata extraction from digital documents. In: International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR 2013), pp, 135–139 (2013)

Councill, I.G., Giles, C.L., Kan, M.-Y.: Parscit: An open-source CRF reference string parsing package. In: Language Resources and Evaluation Conference (LREC 2008), p. 8 (2008)

Krishnamoorthy, M., Nagy, G., Seth, S.: Syntactic segmentation and labeling of digitized pages from technical journals. IEEE Comput. 25(7), 10–22 (1992)

Kudo, T., Yamamoto, K., Matsumoto, Y.: Applying conditional random fields to Japanese morphological analysis. In: Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP 2004) (2004)

Lafferty, J., McCallum, A., Pereira, F.: Conditional random fields: Probabilistic models for segmenting and labeling sequence data. In: Proceedings of 18th International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 282–289 (2001)

Nagy, G., Seth, S., Viswanathan, M.: A prototype document image analysis system for technical journals. IEEE Comput. 25(7), 10–22 (1992)

Nicolas, S., Dardenne, J., Paquet, T., Heutte, L.: Document image segmentation using a 2D conditional random field model. In: International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR 2007), pp. 407–411 (2007)

Ohta, M., Inoue, R., Takasu, A.: Empirical evaluation of active sampling for CRF-based analysis of pages. In: IEEE International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration (IRI 2010), pp. 13–18 (2010)

Ohta, M., Takasu, A.: CRF-based authors’ name tagging for scanned documents. In: Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL 2008), pp. 272–275 (2008)

Ohta, M., Takasu, A., Adachi, J.: Empirical evaluation of CRF-based bibliography extraction from reference strings. In: IAPR International Workshop on Document Analysis Systems (DAS 2014), pp. 287–292 (2014)

Pan, S.J., Yang, Q.: A survey on transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 20(10), 1345–1359 (2010)

Peng, F., McCallum, A.: Accurate information extraction from research papers using conditional random fields. In: Human Language Technologies; Annual Conference on the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Liguistics (NAACL HLT), pp. 329–336 (2004)

Saar-Tsechansky, M., Provost, F.: Active sampling for class probability estimation and ranking. Mach. Learn. 54(2), 153–178 (2004)

Story, G.A., O’Gorman, L., Fox, D., Schaper, L.L., Jagadish, H.V.: The rightpages image-based electronic library for alerting and browsing. IEEE Comput. 25(9), 17–26 (1992)

Takasu, A.: Bibliographic attribute extraction from erroneous references based on a statistical model. In: Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL 2003), pp. 49–60 (2003)

Takasu, A., Ohta, M.: Rule management for information extraction from title pages of academic papers. In: 3rd International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods (ICPRAM 2014), pp. 438–444 (2014)

Wang, Y., Phillips, I.T., Robert, R.M., Haralick, M.: Table structure understanding and its performance evaluation. Pattern Recogn. 37(7), 1479–1497 (2004)

Zanibbi, R., Blostein, D.: Recognition and retrieval of mathematical expressions. Int. J. Doc. Anal. Recogn. 15(4), 331–357 (2012)

Zhu, J., Nie, Z., Wen, J.-R., Zhang, B., Ma, W.-Y.: 2D conditional random fields for web information extraction. In: International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2005) (2005)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper

Takasu, A., Ohta, M. (2015). Utilization of Multiple Sequence Analyzers for Bibliographic Information Extraction. In: Fred, A., De Marsico, M., Tabbone, A. (eds) Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods. ICPRAM 2014. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 9443. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25530-9_15

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25530-9_15

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-25529-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-25530-9

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)