Abstract

In the last few decades, the demand for safer environmental conditions has increased dramatically. The burden of infectious diseases worldwide, related to contamination via contact with contaminated surfaces (fomites), is a growing issue. Globally, these infections are linked to an estimated 1.7 million deaths a year from diarrheal disease and 1.5 million deaths from respiratory infections [1]. Apart from hospitals, the problem has become a growing liability at places where food is prepared and handled [2], where there is a growing risk associated with the cross-contamination of edible goods and where large amounts are handled by a single facility [3]. Already many E. coli and Salmonella outbreaks have been recorded and linked to single a facility [2, 4, 5]. The problem of cross-contamination via surfaces can also be traced, in smaller scale, to households where common areas can accumulate pathogens that can potentially become a threat, especially to more sensitive population groups [6]. There are also biological threats in forms of dangerous epidemic outbreaks (Ebola and SARS) and biological warfare weapons (anthrax and smallpox). The need for effective and efficient disinfection is driving the industry in the development of a wide range of products. These products can currently be divided into three major categories:

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Introduction

In the last few decades, the demand for safer environmental conditions has increased dramatically. The burden of infectious diseases worldwide, related to contamination via contact with contaminated surfaces (fomites), is a growing issue. Globally, these infections are linked to an estimated 1.7 million deaths a year from diarrheal disease and 1.5 million deaths from respiratory infections [1]. Apart from hospitals, the problem has become a growing liability at places where food is prepared and handled [2], where there is a growing risk associated with the cross-contamination of edible goods and where large amounts are handled by a single facility [3]. Already many E. coli and Salmonella outbreaks have been recorded and linked to single a facility [2, 4, 5]. The problem of cross-contamination via surfaces can also be traced, in smaller scale, to households where common areas can accumulate pathogens that can potentially become a threat, especially to more sensitive population groups [6]. There are also biological threats in forms of dangerous epidemic outbreaks (Ebola and SARS) and biological warfare weapons (anthrax and smallpox). The need for effective and efficient disinfection is driving the industry in the development of a wide range of products. These products can currently be divided into three major categories:

-

Chemical disinfectants: Chemical-based disinfectants are currently the majority of the commercial disinfectants, and they have been used for the longest time. Most of them are chlorine-, alcohol-, or ammonium-based products. They are in liquid form and therefore are limited to surfaces. The majority is used to disinfect contaminated surfaces and not as a prevention of contamination. Although their use is relatively simple and easy, they can still be dangerous if they are misused. Gases can also be used for the disinfection. However, the use of other disinfection methods which are based on the use of biocidal gases such ethylene oxide [7], hydrogen peroxide [8], ozone [9], and chlorine dioxide [10] also has limitations associated with toxicity [11] potential material damage, and in some instances downtime of the space or equipment being treated.

-

Radiation-based disinfection: Radiation is a very effective technique since it can immediately inactivate the majority of the contaminants without damaging the surroundings [9, 12, 13]. Still however, the use is limited since it usually requires expensive equipment and under certain conditions, exposure to the used radiation can be proved dangerous [9, 14].

-

Passive disinfectants: Passive disinfectants are characterized as those that do not require a certain application (chemicals) or operation (radiation), but constantly purify and clean surfaces, air, and water. Current air disinfection technologies, such as the use of upper-room UV-C irradiation (Ultraviolet 254 nm), [9, 12] high efficiency particulate (HEPA), and air filtration [15], have shortcomings. UV is associated with health risks [14, 16], requires the upper-room installation of UV fixtures, and relies on a well-mixed air concept. HEPA filters remove bacteria and viruses from the air effectively, but there are excessive costs associated with the energy needed to move air through the filter, and for filter replacement [17]. In addition, they do not deactivate the contaminants; so, if they are not replaced regularly, they can become a source of contamination rather than disinfection medium.

One of the most promising and rapidly emerging means of disinfection is photocatalysis, which does not share any of the shortcomings of the aforementioned methods. Photocatalysis is the type of reaction that takes place on the surface of a certain type of material in the presence of a very specific range of radiation [18]. There is a large selection of materials that can display this type of reaction, but the most widely used is titanium dioxide, TiO2, or titania. Titania in addition to the high efficiency is cheap and environmentally safe, already used widely as pigment and food additive. However, there are significant limitations, which constrain the wider range of applications. Among them, the most notable is the relative low efficiency as compared to the chemical techniques.

In the last decade, one of the methods that has gained a great deal of attention is the combination of titania with various carbon structures such as carbon nanotubes (CNT). One of the most important carbon materials (after diamond) is the carbon nanotube, discovered in 1991 [19]. Their unique properties arise from their structure. Although they possess a large number of unique properties, probably, the most outstanding are their electric properties. In addition, their needle-like shape results in very high specific surface area. Both characteristics (electric properties and high surface area) are essential to the enhancement of photocatalysis, as will be evident in this chapter.

In this book chapter, we outline the major principles of photocatalysis and we examine the methods that have been developed to enhance it. In addition, we discuss the major properties of the carbon nanostructures such as single and multiwall carbon nanotubes (SWNT and MWNT, respectively) and fullerenes and polyhydroxyl fullerenes (C60 and PHF) and how they can be combined with titania in a form of novel nanostructured materials to enhance the photocatalysis.

Photocatalysis

As described earlier, the term “photocatalysis” is a surface reaction that results in “lysis” (Greek for breakdown) molecules in the presence of light. However, the term “photocatalysis” is still under debate since strictly the term implies the initiation of reactions in the presence of light only, something that is not accurate in the case of semiconductor photocatalysis, since in this case, the presence of the semiconductor is equally important [20].

The first report on photocatalytic activity was by Becquerel in 1839, when he observed voltage and electric current on a silver chloride electrode when it was immersed in electrolyte solution in the presence of sunlight [21]. Generally speaking, all semiconductors can display photocatalytic properties, but usually, the oxides and compound semiconductors are demonstrating significantly better results [22–25]. The ability of a semiconductor to undergo photocatalytic oxidation is governed by the band energy positions of the semiconductor and redox potentials of the acceptor species. The latter is thermodynamically required to be below (more positive than) the conduction band potential of the semiconductor [24, 26]. The potential level of the donor needs to be above (more negative than) the valence band position of the semiconductor in order to donate an electron to the vacant hole. Figure 22.1 shows some of the most popular semiconductor photocatalysts represented with their band energy positions. Among them, TiO2 is the most popular as it is efficient, effective, requires shallow UV radiation, is very cheap to manufacture, environmentally safe, and easily incorporated with other materials. Since 1972, when the ability to split the water under UV radiation was first discovered [27], there has been great work in understanding the mechanism and the reactions that take place.

Schematic diagram representing the main photocatalysts with their band-gap energy. In order to photo-reduce a chemical species, the conductance band of the semiconductor must be more negative than the reduction potential of the chemical species; to photo-oxidize a chemical species, the potential of the valence band has to be more positive than the oxidation potential of the chemical species. The energies are shown for pH 0

Basic Principles

Figure 22.2 schematically represents the steps of photocatalysis. Initially when a photon of proper energy (hν ≥ Eg) strikes the surface of the semiconductor, it generates an electron hole pair (h+–e−). Both electron and holes either recombine or migrate to the surface, where, they proceed with chemical reactions. The holes are generating OH• and the electrons H2O2. A very important factor for those processes is the required time. These reactions are summarized, with the estimated time required for each one [28], measured with laser flash photolysis [29, 30]:

-

Charge-carrier generation

$$ {\mathrm{TiO}}_2+ h\nu \to h+{v}_b+{e^{-}}_{cb},1{0}^{-15}\mathrm{s} $$ -

Charge-carrier trapping

$$ \begin{array}{c}{h^{+}}_{vb}\kern0.3em +>{\mathrm{Ti}}^{\mathrm{IV}}\mathrm{OH}\to {\left\{>\kern-0.3em {\mathrm{Ti}}^{\mathrm{IV}}{\mathrm{OH}}^{\bullet}\right\}}^{+},1{0}^{-8}\mathrm{s}\\ {}{e^{-}}_{cb}\kern0.3em +>{\mathrm{Ti}}^{\mathrm{IV}}\mathrm{OH}\to \left\{>\kern-0.3em {\mathrm{Ti}}^{\mathrm{III}}{\mathrm{OH}}^{\bullet}\right\},1{0}^{-10}\mathrm{s}\\ {}{h^{+}}_{vb}+>{\mathrm{Ti}}^{\mathrm{IV}}\to {\mathrm{Ti}}^{\mathrm{III}},1{0}^{-9}\mathrm{s}\end{array} $$ -

Charge-carrier recombination

e − cb + {TiIVOH•}+ → TiIVOH, 10−7s – The electrons inactivate the holes

h + vb + {TiIIIOH} → TiIVOH, 10−8s – The holes inactivate the electrons

-

Charge-carrier recombination

$$ \begin{array}{c}{\left\{>\kern-0.3em {\mathrm{Ti}}^{\mathrm{IV}}{\mathrm{OH}}^{\bullet}\right\}}^{+}+{\mathrm{Red}}^0\to {\mathrm{Ti}}^{\mathrm{IV}}\mathrm{OH}+{\mathrm{Red}}^{\bullet +},1{0}^{-7}\mathrm{s}\\ {}{e_{tr}}^{-}+\mathrm{Ox}\to {\mathrm{Ti}}^{\mathrm{IV}}{\mathrm{OH}}^{\bullet }+{\mathrm{Ox}}^{\bullet +},1{0}^{-3}\mathrm{s}\end{array} $$

Schematic representation of the reactions taking place in titania. (1) Light strikes the semiconductor. (2) An electron–hole pair is formed. (3) Electrons and holes are migrating to the surface. (4) The holes initiate reduction, leading to CO2, Cl− H+, H2O. (5) The conduction band initiate the oxidation. (6) electron and holes recombination to heat or light

According to the above mechanism, the overall quantum efficiency depends on two major types of reactions: the carrier recombination and the OH•/H2O2 generation. The dominant reaction is the recombination of the e− and h+ (1 ns), followed by the reduction reaction (10 ns) and oxidation (1 ms). Since the recombination is also assisted by the localized crystal defects, the remaining carriers are not enough for an efficient photocatalytic reaction, resulting in a low efficient photocatalytic material.

Methods for Enhancing Photocatalytic Reactions

Before we discuss the enhancement of the photocatalysis with the advanced carbon nanocomposites, it is important to investigate the leading mechanisms of that can be used to enhance the photocatalytic reactions. Since 1972, there has been extensive work toward all three types of photocatalytic enhancement with the titania/semiconductor and titania/metal coupling more dominant since they are easier to achieve.

Time-wise the oxidation coming from the holes is the fastest degrading reaction [30]. It is reasonable therefore to favor this reaction over the reduction reaction initiated by the electrons. Since the mechanism that is responsible for the reduced efficiency is the recombination between the h+ and e−, all the previous research has focused on either scavenging the electrons away from the system to prevent recombination, or just retarding the recombination so that the holes will generate OH• [22, 24, 26, 28]: namely, the most common ways are the doping of titania, the coupling with a metal, and the coupling with a semiconductor.

Doping of Titania

A great deal of work has been done the last few decades to dope titania with transition metals, N [31] and C [32, 33]. In general, transition metals are incorporated into the structure of titania and occupy substitutional or interstitial lattice positions. It is a very common defect in the case of semiconductors since it generates trap levels in the band-gap. Figure 22.3a shows the electronic structure of titania before the doping. After the doping (Fig. 22.3b), the band-gap has been modified with the addition of the trapping levels. The trap levels are usually located slightly below the lower edge of the conduction band and usually are in a form of a narrow band.

There are several advantages to this modification. Before the modification, the required photon energy had to satisfy the condition hν ≥ Eg. After the modification, the required energy is going to be hν ≥ (Eg − Et) where Et is the lower edge of the trapping level band. In addition, the electrons that are excited at those levels are trapped, and the holes have sufficient time for OH• generation. Even in the case that hν ≥ Eg and the electron is excited to the conduction band, then during the de-excitation process the electron is going to be transitioned from the conduction band to the trap levels and then to the valence band which again retards the recombination and therefore increases the overall efficiency. This process is subjected to a series of quantum mechanics dictated rules that will allow it or not, but generally, the trap levels generated by the transition metals C and N are satisfying these rules.

The most common transition metals used are Fe+3, Cr+3, and Cu+2. Fe+3 doping of titania has been shown to increase the quantum efficiency for the reduction of N2 [34–36] and methylviologen [34] and to inhibit the electron hole recombination [29, 30, 37]. In the case of phenol degradation, Scalfani et al. [35] and Palmisano et al. [38] reported that Fe+3 had little effect on the efficiency. Enhanced photo-reactivity for water splitting and N2 reduction have been reported with Cr+3 [38–41] doping, while other reports mention the opposite result. Negative effects have been also reported with the Mo and V doping, while Grätzel and Howe reported inhibition of electron hole recombination [42]. Finally, Karakitsou and Verykios noted a positive effect on the efficiency by doping of titania with cations of higher valency than Ti+4 [43]. Butler and Davis [44] and Fujihira et al. [45] reported that Cu+ can also inhibit recombination.

Coupling with a Metal

In photocatalysis, the addition of metals can affect the overall efficiency of the semiconductor by changing the semiconductor’s surface properties. The addition of metal, which is not chemically bonded to the TiO2, can selectively enhance the generation of holes by scavenging away the electrons. The enhancement of the photocatalysis by metal was first observed using the Pt/TiO2 system [46, 47] by increasing the split of H2O to H2 and O2. In particular cases, the addition of metal can affect the reaction products.

Figure 22.4 demonstrates the effect on titania band structure when titania is coupled with a metal. In general, when a semiconductor that has work function φ s is compared with a metal with work function of φ m > φ s, the Fermi level of the semiconductor, E f s, is higher than the Fermi level of the metal E f m (Fig. 22.4a). So when the two materials are brought into contact (Fig. 22.4b), there will be electrons flowing from the semiconductor to the metal until the two Fermi energy levels come to equilibrium. The electrons transition will generate an excess of positive charge that creates an upward band bending. This bending creates a small barrier (in the order of 0.1 eV) that excited electrons can cross and be transported to the metal. From the moment the electrons migrate to the metal, it is not possible to cross back since the barrier for this action is larger, and therefore, the electrons will remain in the metal.

The principles of rectifying contact between titania (Eg = 3.2 eV) and a metal with work function (φm), in this example 5 eV, greater than the affinity (χs) of titania. (a) Before the contact, and (b) after the contact, where a barrier is formed to prevent the electrons of crossing back to the semiconductor. The Eint is the Fermi level if titania is an intrinsic semiconductor and Ef is the Fermi level as an oxygen-deficient material

The earliest work on titania metal was the Pt/TiO2 electrode for the split of water [46, 47]. Currently, one of the most effective metal/TiO2 interface is achieved by colloidal suspension [48]. It was found that in the case of Pt/TiO2 system, the Pt particles are gathered in the form of clusters on the surface of TiO2 [49]. Other metals have also been investigated. Ag has been found to increase the efficiency [50]. Other transition metals such as Cr+3 negatively modify the surface by creating recombination sites. Although in principle all metals can be used, noble metals are preferred since they have higher work function and better conductivity. In all cases, high solids loading will affect the kinetics of the system, the light distribution, and eventually decrease the overall efficiency [48]. Although composite materials with TiO2 coatings have been attempted, the relatively inert surface of the metals does not allow for a chemical bonding, resulting in flaking off of the titania coating.

Coupling with a Semiconductor

Coupling a semiconductor with a photocatalyst is a very interesting way of assisting the photocatalysis. Figure 22.5 demonstrates the principles of the TiO2 coupling with another semiconductor. When two semiconductors are brought together, as in the previous case, the Fermi levels tend to balance, so electrons are flowing from the semiconductor with the highest Fermi level to the semiconductor with the lowest.

The principles of rectifying contact between anatase (α) titania (Eg = 3.2 eV) and rutile (r) titania (Erg = 3.0 eV). (a) Before the contact and (b) after the contact, where a barrier is forming to prevent the electrons created in anatase crossing to the utile. On the other hand, holes created into anatase can migrate to rutile. So the couple of anatase − rutile is creating an effective electron–hole separation

This charge transfer will create an excess of positive charge to the semiconductor that had the highest Fermi level and an excess of negative charge to the semiconductor that had the lowest energy (Fig. 22.5b). In the example in Fig. 22.5, the cases of anatase and rutile (both crystal phases of TiO2) are examined as they are one of the most successful photocatalytic nanocomposites. By light illumination, e − −h + pairs are generated in both semiconductors. The barrier that forms separates the electrons in the conduction band, but at the valence band, the holes are free to move, and based on the energy diagram, they move from the semiconductor with the larger gap to the one with the smaller. In this case, the composite material is acting as a charge separator. The holes are gathered in the rutile where they create an excess of holes, and despite the fact that the recombination is still the main process, the excess of holes will be enough to photo-oxidize the organic molecules.

In addition, semiconductors can be used as a hole or electron injector. In order to achieve optimum results, a candidate semiconductor has to satisfy the following criteria.

-

Have a proper band-gap

-

Have a proper position of the Fermi energy level

-

Have proper relative position of the conduction and valence band to the vacuum level

The combination of the band-gap and Fermi level will determine if there are holes or electrons that will be transported and toward which direction. Thus, in order for a semiconductor coupled with titania to enhance the photocatalysis, the semiconductor has to have very specific properties. This is the reason that this technique, despite its simplicity, ease of manufacturing, and very promising results, is not very widely applied. Systems that have been developed are the TiO2/CdS [51], TiO2/RuO2 [52, 53], and anatase-TiO2/rutile-TiO2 [54, 55]. The last one is a system commercially available from Degussa, known as Aeroxide P25, and is the most powerful commercial, particulate, photocatalytic system [55]. The excellent and uniform properties have established it as benchmark material to compare photocatalytic efficiencies.

Carbon Nanotubes

Carbon nanotubes were discovered by Iijima [56] in 1991 and since their discovery, they have attracted a great deal of attention due to the exceptional electric [57], thermal, and mechanical properties [58]. Iijima reported the creation of multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWNT) with outer diameter up to 55 Å and inner diameter down to 23 Å. Since that time, extensive theoretical and experimental research for the past decade has led to the creation of a rapidly developing research field. In 1993, Bethune et al. [59] reported the discovery of the single-wall nanotubes (SWNT). The very small diameter of the single nanotubes and the very big length makes them to behave as quantum wires, giving them very interesting properties. Due to the fact that the SWNT usually contains a small number of carbon atoms (usually < 102), they have attracted almost all the theoretical work. They possess some remarkable electronic, mechanical, and thermal properties that are related mainly to their diameter and chirality. Due to their importance and relevance to the photocatalysis, the electronic properties will be discussed in more detail later.

Structure

The CNTs can be thought as rolled graphene sheets that are held by the bonding of the sp2 orbital. However, due to the curvature of the tube, the σ and π bonds are going to be re-hybridized. The new structure pushes σ bonds out of the plane, all at the same direction (toward the center of the tube). To compromise the charge shift, the π bond will be delocalized to the direction outside the tube. This configuration will make the tubes mechanically stronger and electrically and thermally more conducting than graphite. The flexibility of the σ bond allows the incorporation of topological defects, such as pentagons or heptagons, that allow the formation of caps, bend, toroidal, or helical tubes.

The direction the graphene sheet is “rolled” to produce the nanotubes is referred to as chirality. Without going into detail, it should be mentioned that the chirality essentially defines the amount of the deformations the orbitals undergo which further define the type of nanotubes. It is beyond the scope of the chapter to get into detail on the types and the related notation that is used, but we can mention the zigzag type tubes and the armchair, names directly related to the rolling direction. Although the properties that arise are very interesting, it is beyond the scope of the book chapter. The interested reader can find more information elsewhere [19, 60, 61].

Electronic Properties

Their unique electronic properties are attributed to the different quantum confinement of electrons. We can see three different directions that based on the geometry it will result in, or not confinement. (i) In the radial direction, electrons are confined by the monolayer thickness of the graphene sheet. (ii) Around the circumference of the nanotube, periodic boundary conditions come into play. (iii) Finally the direction parallel to the axis, since it is considered infinite, there is no confinement. The last one defines the conductivity of the SWNT. The longitudinal confinements largely depend on the chirality of the nanotube. Regarding the SWNT conductivity, 1/3 of the zigzag nanotubes are conducting, meaning they do not have any band-gap and the electrons are free to move toward any direction. On the other hand, the armchairs are all conducting.

However, the multiwall nanotubes are very different as they behave as a wire, regardless of the chirality of the bundle tubes or their number. The estimated conductance follows the simple relation [62];

For the case of the MWNT, the value of M is significantly bigger than for the SWNT to account for more conducting channels. In addition, the multilayer structure increases the probability to have armchair or zigzag tubes that will increase the conductivity. While the diameter is increasing, the electrons on the tube are less confined and the electron distribution resembles more the structure of graphite. This is due to the rehybridization of the σ and π orbitals, that is less intense and the tubular structure approaches more the graphite structure. This basically means that while the tube diameter increases, the energy gap is diminishing even for the semiconducting tubes. So in general, MWNTs are in their majority conducting and behave as nanowires. But, there are still chances that the tubes will be semiconducting, depending always on the arrangement of the tubes, certain crystal defects, and purity.

Although these properties are essential for the success or failure of the photocatalytic composites, they are often overlooked, either because they are not considered important or because it is very hard to control them.

Synthesis

There is a tremendous amount of research that has been done for the last 30 years in the field of the carbon nanotube growth. However, the majority of the methods are still based on the two leading methods that have been widely used the arc discharge and the CVD. The method of production is essential in the photocatalytic composites as it impacts directly the structure and the quality of the nanotubes.

Arc Discharge

In general, carbon nanotubes that are produced with carbon vapor that is being created by the arc discharge have fewer defects compared to other techniques. The reason for that is the high growth process temperature that ensures perfect annealing that eliminates most of the defects. The MWNTs that are produced via arc discharge are perfectly straight. The fewer defects have an immediate dramatic impact on the tube properties such as electric and mechanical. One of the main disadvantages is the limited yield that this method has. Besides the low yield, it is a highly time-consuming process. So in general, if a high yield of nanotubes is required, this method is not recommended; on the contrary, if more defined and better properties are required, then arc discharge is a very good solution [63].

Thermal- or Plasma-Enhanced CVD

Since the application field of the nanotubes is growing, the demand for higher yield production methods is also growing. One of the most promising techniques is the chemical vapor deposition (CVD). The apparatus for CVD-grown nanotubes is simple, which is also reducing a lot of the cost of the production. The growth rates can be controlled precisely and can go from a few nm/min up to 5 μm/min. Moreover, metal catalyst can further assist the yield. In addition, the nanotubes that are CVD grown have a lot of structural defects due to the low synthesis temperature during the growth process. An approach to improve this is annealing the tubes, which will reduce the defects but in no case will have the same results as the arc discharge [63]. The purification of the tubes in this case is a necessity since they contain metal catalyst and different amorphous carbon structures.

There are many ways to purify the tubes: hydrothermal treatment [64], H2O-plasma oxidation [65], acid oxidation [66], dispersion and separation by micro-filtration [67], and high-performance liquid chromatography [68].

Carbon Nanotubes–TiO2 Composites

It is obvious from the previous discussion regarding the photocatalysis and the CNTs, that the combination of MWNTs or SWNTs and TiO2, in one composite will deliver a new material with high photocatalytic efficiency.

Both MWNTs and SWNTs have a variety of electronic properties useful for photocatalytic enhancement. MWNTs can behave as metals, exhibiting metallic conductivity. Alternatively, the SWNTs can exhibit semiconducting properties which is a well-documented mechanism to enhance photocatalysis (discussed in the previous section). However, in addition to the intrinsic electronic properties and the CNT have also a very high surface area. Since photocatalysis is a surface reaction, more surface means more efficiency. In addition, CNTs due to their black color can further assist the photocatalysis by further increasing the amount of the adsorbed light. As explained, TiO2 requires UV light in order to excite an electron with enough energy to overcome the band-gap. The UV spectrum represents only 5 % of the available total sunlight spectrum. Being able to use a larger portion of the spectrum of natural sunlight for photocatalysis is an important aspect for commercialization of the technology as UV usage is not always recommended [69].

Beyond the surface area and the higher adsorption, the surface of the CNTs can be tailored to increase specificity toward particular pollutants (molecular or biological) through the attachment of specific surface groups. When purified via acid treatment, CNTs formed alcohol, keto, and acid moieties on their surfaces. These groups can be further modified to improve adsorption of specific species, an advantage over activated carbons that are typically nonselective and have a lower pollutant-degradation rate due to the degradation of all species (benign and pollutant) present [70].

Synthesis Routes of the CNT–TiO2 Composites

The precise control required to achieve the nanothin layer of titania on the MWNTs limits the methods that the CNT/TiO2 can be synthesized. The most common method is the sol–gel chemistry [69, 71–77], which not only provides the precise control but also creates the strong adhesion due to the bonding between the coating and the MWNTs, a very important parameter for reasons that will be obvious later. In addition, there are reports where the coating has been synthesized via the hydrothermal method, which can have much higher yield, very important for commercialization of the composite [71, 78–80].

The variations in the synthesis method can also be seen on the structure of the final product. In one case, there is the formation of a uniform thin coating of titania around the MWNTs. In this case, the MWNTs’ surface acts as a catalyst to initiate the nucleation of the TiO2 formation, resulting in a thin uniform layer thickness. Alternatively, there is the formation of the titania nanoparticles on the surface of the nanotubes which is actually one of the most common configurations. This is typically achieved by nucleating and growing titania on dispersed CNTs in a liquid medium. A drawback is the formation of free titania nanoparticles instead of only those on the surface of nanoparticles.

The sol–gel coating of CNTs is performed in a liquid medium, alcohol, or water, based on the sol–gel reactions [69, 72, 73, 81]. Therefore, one of the biggest challenges is the proper dispersion of the CNTs. Improper dispersion will result in coating MWNTs aggregates instead of the single MWNTs. This is not a trivial task since the graphite sheet of the MWNTs is hydrophobic, making this task almost impossible. Sun and Gao [82] developed a method to increase hydrophilicity of CNTs dispersible in water via heating in an ammonia atmosphere at 600 °C. Other methods use surface charges stemming from acid groups that were introduced by treatments in hot oxidizing mineral acids [73, 77, 83]. This process results in the generation of –OH and –COOH groups on the surface of the nanotubes. These groups make the CNTs hydrophilic making them dispersible in water and in addition act as nucleation points for the coating to initiate.

For sol–gel, the most common precursors are the various metal alkoxides, (R–O–)4Ti. The most common characteristic of the titanium alkoxide precursors is their high reactivity with water to yield TiO2, which in general is amorphous at room temperature with small seeds of anatase phase. The reactivity controls the speed of the reactions and therefore the uniformity of the coating. Faster reaction rates usually result in large particle-size distributions of the primary particles. The addition of acids or bases is one possibility to change the reaction rate [69, 72, 73, 81]. The reactivity is controlled primarily from the chain length of the alkoxide with longer chain resulting in slower reaction. The most common precursor is titanium isopropoxide [69, 72, 77], since it combines several desirable characteristics. It readily dissolves in alcohols and is not overly sensitive to humidity. An alternative is titanium butoxide [73, 78], which is even less sensitive to humidity; however, its higher viscosity may cause problems when dissolving it in ethanol at high concentrations. There are also reports where titanium ethoxide was used, but it is preferred for the formation of TiO2 particles on the surface of the nanotubes, since the precise control of the reaction is very hard [71]. Alternatives to the titanium alkoxides in sol–gel are titanium tetrachloride [53] and titanium oxysulfate (TiOSO4) [78], which have been used in the past for the synthesis of TiO2 rutile and anatase particles, respectively. These precursors can be used in water, but this requires the CNTs to be dispersed in water, which can be challenging. Recently, CNTs have also been coated via hydrothermal methods [53, 71, 78–80] using mostly titanium tetrachloride [53] and TiOSO4 [78].

Regardless of the chosen conditions and chemistry, the final material is mostly amorphous TiO2 with seeds of anatase. It is therefore required a heat treatment to fully crystallize the coating. It usually occurs in nitrogen atmosphere at 300–500 °C to avoid the burnout of the CNTs and the phase transformation from anatase to rutile respectively [84]. It is worth mentioning that the coating of single-wall nanotubes was reported only recently [85, 86]. Single-wall CNT coatings are of importance since the electronic properties of tubes are better defined than in multiwalled CNTs. This will allow for better experiments to verify the proposed mechanisms.

A relatively new method of preparing such composites is the filter-mat or fiber-form via the electrospinning method [75, 77, 87]. Such methods produce mm to m long fibers with 40–100 nm in diameter. Typically, a fiber mat is formed, which is currently explored for a variety of catalytic applications. Such methodologies again involve chemistries very similar to the sol–gel route. One of the major differences is the addition of a polymer to form the backbone of the structure. Huey and Sigmund [88] have measured the mechanical properties of such fibers. The modulus of elasticity was found to be above 250 GPa for the CNT reinforced anatase nanofibers, which is significantly higher compared to less than 100 GPa, which was found for the electrospun pure anatase nanofibers. As electrospray is widely used for coatings of surfaces this method has a great potential.

Mechanisms of Photocatalysis Enhancement in CNT–TiO2 Composites

Beyond the obvious, high surface area, the high surface energy (leading to higher adsorption), and the enhancement of light adsorption, there is a number of prevailing theories used to explain the enhancement of the photocatalytic properties of CNT–TiO2 composites.

One mechanism, proposed by Wang et al. [80], states that the CNTs act as sensitizers and transfer electrons to the TiO2. The photogenerated electrons are then injected into the conduction band of the TiO2, allowing for the formation of superoxide radicals by adsorbed molecular oxygen. Once this occurs, the positively charged nanotubes remove an electron from the valence band of the TiO2, leaving a hole. The now positively charged TiO2 can then react with adsorbed water to form hydroxyl radicals.

Another mechanism, proposed by Pyrgiotakis, is a based on the theories described above as methods for the enhancement coupling with a metal or a semiconductor following the mechanisms explained in the related theory (Figs. 22.4 and 22.5). A high-energy photon excites an electron from the valence band to the conduction band of TiO2. As discussed the recombination of the hole and electron is the dominant mechanism. The nanotubes especially those that have metallic properties can accept the photogenerated electrons, leaving the holes in the TiO2 to take part in redox reactions. However, according to the theory of photocatalysis, the work function is a critical parameter to the creation of the rectifying contact. Table 22.1 compares the work function of the nanotubes to the work function of other traditional metals among which are Pt and Au, both used to improve photocatalysis. Carbon nanotubes compare very well with the other metals, since they are only slightly below Au. Therefore, the utilization of carbon nanotubes as the core of the photocatalytic composite is expected to enhance the photocatalysis since it has the ability to increase the efficiency by both methods mentioned earlier, high specific area and metallic properties. In addition, as it was discussed earlier, carbon can act as a dopant to the titania structure.

In this scheme, the carbon can generate trap levels in the band-gap that can change the transition of the electrons trapping them for short period of time. This gives time to the hole to lead the reduction reaction.

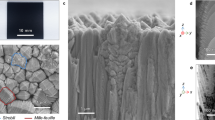

Although according to above mechanisms, all CNT–TiO2 composites should preform based on this mechanism, this is not the case, as these systems are more complex. There are two parameters that are very important for the CNT–TiO2 composite to work. The most essential parameter is the electronic configuration of the CNTs. It was shown by Pyrgiotakis that although CVD and arc-discharge-synthesized CNTs appear to have the same properties, number of tubes, diameter, etc., their core electronic properties are drastically different (Fig. 22.6a, b) [89]. As it was described in section “Electronic Properties”, the electronic properties of the nanotubes depend on the coherence of the various layer of the MWNT. The catalyst-assisted CVD-grown MWNTs result in a more random growth, while the lower temperature of the reactor prevents the various defects to self-correct. This results in a large number of defects that compromise the electrical properties of the MWNTs. Although at macroscopic level, those defects do not significantly impact their usage, this become essential at the nanoscale level. In the case of photocatalysis, the electrons need to transit to the underlying MWNT. If, however, there are defects, the electrons’ ability to transfer to the MWNT is reduced, impacting significantly the photocatalyitc ability of the CNT–TiO2 composites. This was proved experimentally by Pyrgiotakis where both arc discharge- and CVD-grown MWNTs were coated with TiO2 via sol–gel processes. Although both nanocomposites were structurally similar under the TEM, the photocatalytic activity was ten higher for the arc discharge MWNT compared to the CVD-grown nanotubes. However, even in the case of the CVD-grown MWNTs, the enhanced photocatalytic activity can still occur mainly due to the fact that the tubes still provide an electron depository, carbon doping, high surface area, higher light adsorption, and higher pollutant adsorption.

In addition to the quality of the MWNTs, there is an equally important parameter; the carbon–oxygen–titanium bond. This bond serves two different purposes: From one side, this bond can activate the carbon as dopant for the titania, similar to carbon-doped titania, and on the other side, it is a channel to transfer the electrons to the MWNT. A composite that does not have this bond will be missing the dopant mechanism and will have significantly reduced ability to transport the electrons. Pyrgiotakis confirm the presence of Ti–O–C bonds in both types of nanocomposites with X-Ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) [90], Raman Spectroscopy and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) [89]. In addition to the confirmation of the bond, Raman spectroscopy confirmed that arc-discharge-synthesized CNTs must have a higher electrical conductivity and fewer defects. This is also supported by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the nanocomposites. The bond was later confirmed by Wang et al. in composites synthesized via the hydrothermal process [80].

Conclusion

Titania and carbon nanotubes composites are very promising solution for a wide range of biocidal applications. As it was evident from the discussion, the various properties of the nanotubes are among the main reasons that the nanotubes can assist the photocatalysis when they are in colloidal suspension. However, the application of a thin TiO2 coating on the carbon nanotubes is not enough to yield very high photocatalytic efficiency. As it was shown, the bond (C−O−Ti) created between the MWNTs and the TiO2 is essential for the creation of a highly reliable photocatalytic material [90]. The bond makes the underlined carbon atoms dopants to the structure of titania and provides a channel for the electrons to diffuse to the nanotube. However, the metallic nature of the carbon nanotubes is equally critical as the bond. Overall, carbon in the form of carbon nanotubes can be a very promising way to enhance the photocatalysis, but the carbon nanotubes must be very well defined, with distinct structure and good electrical properties.

Over the years, this work was expanded and now similar nanocomposites are made with other forms of carbon such as fullerenes [91], polyhydroxyl fullerenes (PHF) [92], and graphene [93]. Although due to the size of the fullerenes, the fullerenes are applied as a coating to titania, the main principles remain the same. However, large concentration of fullerenes can affect the light adsorption, compromising the photocatalytic reaction. Krishna et al. showed that the ideal mass ratio is 0.001 C60/TiO2 [92]. For the case of the graphene, small titania particles are nucleating on the surface and the process is similar to the nanotubes. However, the exposed graphene can be a chemical magnet for contaminants attracting them, further increasing the overall efficiency [94].

References

Osseiran N, Hartl G (2006) WHO | Almost a quarter of all disease caused by environmental exposure. WHO 14:159–167 and 188

Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig LF, Bresee JS, Shapiro C et al (1999) Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis 5:607–625

Luber P, Brynestad S, Topsch D, Scherer K, Bartelt E (2006) Quantification of campylobacter species cross-contamination during handling of contaminated fresh chicken parts in kitchens. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:66–70

World Health Organization (2008) Foodborne disease outbreaks: guidelines for investigation and control. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Redmond EC, Griffith CJ, Slader J, Humphrey TJ (2004) Microbiological and observational analysis of cross contamination risks during domestic food preparation. Br Food J 106:581–597

Scott E (1999) Hygiene issues in the home. Am J Infect Control 27:S22–S25

Chang FM, Sakai Y, Ashizawa S (1973) Bacterial pollution and disinfection of the colonofiberscope. II. Ethylene oxide gas sterilization. Am J Dig Dis 18:651–658

Krause J, McDonnell G, Riedesel H (2001) Biodecontamination of animal rooms and heat-sensitive equipment with vaporized hydrogen peroxide. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 40:18–21

Kujundzic E, Matalkah F, Howard CJ, Hernandez M, Miller SL (2006) UV air cleaners and upper-room air ultraviolet germicidal irradiation for controlling airborne bacteria and fungal spores. J Occup Environ Hyg 3:536–546

Taylor RH, Falkinham JO, Norton CD, LeChevallier MW (2000) Chlorine, chloramine, chlorine dioxide, and ozone susceptibility of Mycobacterium avium. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:1702–1705

Connor AJ, Laskin JD, Laskin DL (2012) Ozone-induced lung injury and sterile inflammation. Role of toll-like receptor 4. Exp Mol Pathol 92:229–235

Lai KM, Burge HA, First MW (2004) Size and UV germicidal irradiation susceptibility of Serratia marcescens when aerosolized from different suspending media. Appl Environ Microbiol 70:2021–2027

McDevitt JJ, Rudnick SN, Radonovich LJ (2012) Aerosol susceptibility of influenza virus to UV-C light. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:1666–1669

Zaffina S, Camisa V, Lembo M, Vinci MR, Tucci MG, Borra M et al (2012) Accidental exposure to UV radiation produced by germicidal lamp: case report and risk assessment. Photochem Photobiol 88:1001–1004

Mead K, Johnson DL (2004) An evaluation of portable high-efficiency particulate air filtration for expedient patient isolation in epidemic and emergency response. Ann Emerg Med 44:635–645

Kligman LH, Akin FJ, Kligman AM (1985) The contributions of UVA and UVB to connective tissue damage in hairless mice. J Invest Dermatol 84:272–276

Adal KA, Anglim AM, Palumbo CL, Titus MG, Coyner BJ, Farr BM (1994) The use of high-efficiency particulate air-filter respirators to protect hospital workers from tuberculosis. A cost-effectiveness analysis. N Engl J Med 331:169–173

Suppan P (1994) Chemistry and light. The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, UK

Dresselhaus M, Dresselhaus G, Saito R (1995) Physics of carbon nanotubes. Carbon 33:883–891

Gupta SM, Tripathi M (2011) An overview of commonly used semiconductor nanoparticles in photocatalysis. High Energy Chem 46:1–9

Becquerel E (1839) Mçmoire sur les effets électriques produits sous l’influence des rayons solaires. Comptes Rendus De l’Academie Des Sciences 9:561–567

Fox MA, Dulay MT (1996) Acceleration of secondary dark reactions of intermediates derived from adsorbed dyes on irradiated TiO2 powders. J Photochem Photobiol A 98:91–101

Intra P, Tippayawong N (2008) An overview of differential mobility analyzers for size classification of nanometer-sized aerosol particles. Songklanakarin J Sci Technol 30:243–256

Linsebigler AL, Lu G, Yates JT (1995) Photocatalysis on TiO2 surfaces: principles, mechanisms, and selected results. Chem Rev 95:735–758

Kühn KP, Chaberny IF, Massholder K, Stickler M, Benz VW, Sonntag H-G et al (2003) Disinfection of surfaces by photocatalytic oxidation with titanium dioxide and UVA light. Chemosphere 53:71–77

Mills G, Hoffmann MR (1993) Photocatalytic degradation of pentachlorophenol on TiO2 particles - identification of intermediates and mechanism of reaction. Environ Sci Technol 27:1681–1689

Fujishima A, Honda K (1972) Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 238:37–40

Hoffmann MR, Martin ST, Choi WY, Bahnemann DW (1995) Environmental applications of semiconductor photocatalysis. Chem Rev 95:69–96

Martin ST, Herrmann H, Hoffmann MR (1994) Time-resolved microwave conductivity. Part 1. Quantum-sized TiO2 and the effect of adsorbates and light-intensity on charge-carrier dynamics. J Chem Soc-Faraday Trans 90:3323–3330

Martin ST, Herrmann H, Choi WY, Hoffmann MR (1994) Time-resolved microwave conductivity. Part 2. TiO2 photoreactivity and size quantization. J Chem Soc-Faraday Trans 90:3315–3322

Khan SUM, Al-Shahry M, Ingler WB (2002) Efficient photochemical water splitting by a chemically modified n-TiO2. Science 297:2243–2245

Irie H, Watanabe Y, Hashimoto K (2003) Carbon-doped anatase TiO2 powders as a visible-light sensitive photocatalyst. Chem Lett 32:772–773

Sakthivel S, Kisch H (2003) Daylight photocatalysis by carbon-modified titanium dioxide. Angew Chem Int Ed 42:4908–4911

Moser J, Gratzel M, Gallay R (1987) Inhibition of electron–hole recombination in substitutionally doped colloidal semiconductor crystallites. Helv Chim Acta 70:1596–1604

Sclafani A, Palmisano L, Schiavello M (1992) Phenol and nitrophenols photodegradation carried out using aqueous TiO2 anatase dispersions. Abstracts of Papers of the Amercian Chemical Society. 203:132–ENVR

Soria J, Conesa JC, Augugliaro V, Palmisano L, Schiavello M, Sclafani A (1991) Dinitrogen photoreduction to ammonia over titanium-dioxide powders doped with ferric ions. J Phys Chem 95:274–282

Choi WY, Termin A, Hoffmann MR (1994) Effects of metal-ion dopants on the photocatalytic reactivity of quantum-sized TiO2 particles. Angew Chem Int Ed 33:1091–1092

Palmisano L, Augugliaro V, Sclafani A, Schiavello M (1988) Activity of chromium-ion-doped titania for the dinitrogen photoreduction to ammonia and for the phenol photodegradation. J Phys Chem 92:6710–6713

Herrmann JM, Disdier J, Pichat P (1984) Effect of chromium doping on the electrical and catalytic properties of powder titania under UV and visible illumination. Chem Phys Lett 108:618–622

Mu W, Herrmann JM, Pichat P (1989) Room-temperature photocatalytic oxidation of liquid cyclohexane into cyclohexanone over neat and modified TiO2. Catal Lett 3:73–84

Sun B, Reddy EP, Smirniotis PG (2005) Effect of the Cr6+ concentration in Cr-incorporated TiO2-loaded MCM-41 catalysts for visible light photocatalysis. Appl Catal B-Environ 57:139–149

Grätzel M (1999) Mesoporous oxide junctions and nanostructured solar cells. Curr Opin Colloid Interface Sci 4:314–321

Karakitsou KE, Verykios XE (1993) Effects of altervalent cation doping of TiO2 on its performance as a photocatalyst for water cleavage. J Phys Chem 97:1184–1189

Butler EC, Davis AP (1993) Photocatalytic oxidation in aqueous titanium-dioxide suspensions - the influence of dissolved transition-metals. J Photochem Photobiol A 70:273–283

Fujihira M, Satoh Y, Osa T (1982) Heterogeneous photocatalytic reactions on semiconductor-materials. 3. Effect of Ph and Cu2+ ions on the photo-Fenton type reaction. Bull Chem Soc Jpn 55:666–671

Sato S, White JM (1980) Photo-decomposition of water over Pt-TiO2 catalysts. Chem Phys Lett 72:83–86

Sato S, White JM (1980) Photoassisted reaction of CO2 with H2O on Pt-TiO2. Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society. 179:75–COLL

Bahnemann D, Bockelmann D, Goslich R (1991) Mechanistic studies of water detoxification in illuminated TiO2 suspensions. Solar Energy Mater 24:564–583

Pichat P, Mozzanega MN, Disdier J, Herrmann JM (1982) Pt content and temperature effects on the photocatalytic H-2 production from aliphatic-alcohols over Pt TiO2. Nouveau J De Chimie-New J Chem 6:559–564

Sclafani A, Mozzanega MN, Pichat P (1991) Effect of silver deposits on the photocatalytic activity of titanium-dioxide samples for the dehydrogenation or oxidation of 2-propanol. J Photochem Photobiol A 59:181–189

Gopidas KR, Bohorquez M, Kamat PV (1990) Photoelectrochemistry in semiconductor particulate systems.16. Photophysical and photochemical aspects of coupled semiconductors - charge-transfer processes in colloidal Cds-TiO2 and Cds-Agi systems. J Phys Chem 94:6435–6440

Duonghong D, Borgarello E, Gratzel M (1981) Dynamics of light-induced water cleavage in colloidal systems. J Am Chem Soc 103:4685–4690

Xia X-H, Jia Z-J, Yu Y, Liang Y, Wang Z, Ma L-L (2007) Preparation of multi-walled carbon nanotube supported TiO2 and its photocatalytic activity in the reduction of CO2 with H2O. Carbon 45:717–721

Hurum DC, Gray KA, Rajh T, Thurnauer MC (2005) Recombination pathways in the Degussa P25 formulation of TiO2: surface versus lattice mechanisms. J Phys Chem B 109:977–980

Sun B, Smirniotis PG (2003) Interaction of anatase and rutile TiO2 particles in aqueous photooxidation. Catal Today 88:49–59

Iijima S (1991) Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 354:56–58

Mintmire J, White C (1995) Electronic and structural properties of carbon nanotubes. Carbon 33:893–902

Ruoff R, Lorents D (1995) Mechanical and thermal properties of carbon nanotubes. Carbon 33:925–930

Bethune DS, Klang CH, de Vries MS, Gorman G, Savoy R, Vazquez J et al (1993) Cobalt-catalysed growth of carbon nanotubes with single-atomic-layer walls. Nature 363:605–607

Dresselhaus MS (2003) Carbon nanotubes. Carbon 33:1–2

Dresselhaus M (1998) New tricks with nanotubes. Nature 391:19–20

Frank S, Poncharal P, Wang ZL, de Heer WA (1998) Carbon nanotube quantum resistors. Science 280:1744–1746

Meyyappan M (2004) Carbon nanotubes: science and applications. CRC, Boca Raton

Tohji K, Takahashi H, Shinoda Y (1997) Purification procedure for single-walled nanotubes. J Phys Chem 101:1974–1978

Huang S, Dai L (2002) Plasma etching for purification and controlled opening of aligned carbon nanotubes. J Phys Chem B 106:3543–3545

Chiang IW, Brinson BE, Smalley RE, Margrave JL, Hauge RH (2001) Purification and characterization of single-wall carbon nanotubes. J Phys Chem B 105:1157–1161

Bandow S, Rao AM, Williams KA, Thess A, Smalley RE, Eklund PC (1997) Purification of single-wall carbon nanotubes by microfiltration. J Phys Chem B 101:8839–8842

Zhao B, Hu H, Niyogi S, Itkis ME, Hamon MA, Bhowmik P et al (2001) Chromatographic purification and properties of soluble single-walled carbon nanotubes. J Am Chem Soc 123:11673–11677

Wang W, Serp P, Kalck P, Faria J (2005) Visible light photodegradation of phenol on MWNT-TiO2 composite catalysts prepared by a modified sol–gel method. J Mol Catal A 235:194–199

Carp O, Huisman CL, Reller A (2004) Photoinduced reactivity of titanium dioxide. Prog Solid State Chem 32:33–177

Jitianu A, Cacciaguerra T, Benoit R, Delpeux S, Beguin F, Bonnamy S (2004) Synthesis and characterization of carbon nanotubes-TiO2 nanocomposites. Carbon 42:1147–1151

Wang W, Serp P, Kalck P, Faria J (2005) Photocatalytic degradation of phenol on MWNT and titania composite catalysts prepared by a modified sol–gel method. Appl Catal B-Environ 56:305–312

Zhu Z, Zhou Y, Yu H, Nomura T, Fugetsu B (2006) Photodegradation of humic substances on MWCNT/Nanotubular-TiO2 composites. Chem Lett 35:890–891

Kuo C-S, Tseng Y-H, Lin H-Y, Huang C-H, Shen C-Y, Li Y-Y et al (2007) Synthesis of a CNT-grafted TiO2 nanocatalyst and its activity triggered by a DC voltage. Nanotechnology 18:465607

Hu G, Meng X, Feng X, Ding Y, Zhang S, Yang M (2007) Anatase TiO2 nanoparticles/carbon nanotubes nanofibers: preparation, characterization and photocatalytic properties. J Mater Sci 42:7162–7170

Rincón A, Pulgarin C (2003) Photocatalytical inactivation of E. coli: effect of (continuous-intermittent) light intensity and of (suspended-fixed) TiO2 concentration. Appl Catal B-Environ 44:263–284

Aryal S, Kim CK, Kim K-W, Khil MS, Kim HY (2008) Multi-walled carbon nanotubes/TiO2 composite nanofiber by electrospinning. Mater Sci Eng C 28:75–79

Yen C-Y, Lin Y-F, Hung C-H, Tseng Y-H, Ma C-CM, Chang M-C et al (2008) The effects of synthesis procedures on the morphology and photocatalytic activity of multi-walled carbon nanotubes/TiO2 nanocomposites. Nanotechnology 19:045604

Byrappa K, Dayananda AS, Sajan CP, Basavalingu B, Shayan MB, Soga K et al (2008) Hydrothermal preparation of ZnO:CNT and TiO2:CNT composites and their photocatalytic applications. J Mater Sci 43:2348–2355

Wang Q, Yang D, Chen D, Wang Y, Jiang Z (2007) Synthesis of anatase titania-carbon nanotubes nanocomposites with enhanced photocatalytic activity through a nanocoating-hydrothermal process. J Nanopart Res 9:1087–1096

Luo X, Zha C, Luther-Davies B (2005) Preparation and optical properties of titania-doped hybrid polymer via anhydrous sol–gel process. J Non Cryst Solids 351:29–34

Sun J, Gao L (2003) Development of a dispersion process for carbon nanotubes in ceramic matrix by heterocoagulation. Carbon 41:1063–1068

Zhu Z, Sun M, Guo Y, Li Y (2007) Effect of phosphorylation on peptidyl-prolyl imide bond cis/trans isomerization of peptides with xaa-pro motif. Prog Biochem Biophys 34:585–594

Lee S-W, Sigmund WM (2003) Formation of anatase TiO2 nanoparticles on carbon nanotubes. Chem Commun 6:780–781

Ahmmad B, Kusumoto Y, Somekawa S, Ikeda M (2008) Carbon nanotubes synergistically enhance photocatalytic activity of TiO2. Catal Commun 9:1410–1413

Ahmmad B, Kusumoto Y, Ikeda M, Somekawa S, Horie Y (2007) Photocatalytic hydrogen production from diacids and their decomposition over mixtures of TiO2 and single walled carbon nanotubes. J Adv Oxidation Technol 10:415–420

Kedem S, Schmidt J, Paz Y, Cohen Y (2005) Composite polymer nanofibers with carbon nanotubes and titanium dioxide particles. Langmuir 21:5600–5604

Huey BD, Sigmund W (2007) The application of scanning probe microscopy in materials science studies. JOM 59:11–11

Pyrgiotakis G (2006) Titania carbon nanotube composites for enhanced photocatalysis. University of Florida

Pyrgiotakis G, Sigmund WM (2010) X-Ray photoelectron spectroscopy of anatase-TiO2 coated carbon nanotubes. Solid State Phenom 162:163–177

Yu J, Ma T, Liu G, Cheng B (2011) Enhanced photocatalytic activity of bimodal mesoporous titania powders by C60 modification. Dalton Trans 40:6635

Krishna V, Noguchi N, Koopman B, Moudgil B (2006) Enhancement of titanium dioxide photocatalysis by water-soluble fullerenes. J Colloid Interface Sci 304:166–171

Ma W, Han D, Zhang N, Li F, Wu T, Dong X et al (2013) Bionic radical generation and antioxidant capacity sensing with photocatalytic graphene oxide–titanium dioxide composites under visible light. Analyst 138:2335–2342

Lee E, Hong J-Y, Kang H, Jang J (2012) Synthesis of TiO2 nanorod-decorated graphene sheets and their highly efficient photocatalytic activities under visible-light irradiation. J Hazard Mater 219–220:13–18

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pyrgiotakis, G. (2014). Carbon Nanostructures for Enhanced Photocatalysis for Biocidal Applications. In: Bhushan, B., Luo, D., Schricker, S., Sigmund, W., Zauscher, S. (eds) Handbook of Nanomaterials Properties. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-31107-9_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-31107-9_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-642-31106-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-642-31107-9

eBook Packages: Chemistry and Materials ScienceChemistry and Material Science (R0)